Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n3a2186

ARTICLES

Reflections of South African educators on the enablement of at-risk learners with protective systems via the Read-me-to-Resilience intervention

Carmen Joubert

School of Psycho-Social Education and COMBER Research Entity, Faculty of Education, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa. carmen.joubert@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Resilience-promoting interventions, such as the Read-me-to-Resilience intervention strategy, that consists of culturally relevant indigenous stories has been shown to encourage resilience in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) orphans. In this study, educator participants reflected on the protective systems that the Read-me-to-Resilience stories might offer for at-risk learners within their school context. Resilience protective systems include self-regulation, attachment relationships, agency and mastery motivation systems, cultural traditions and religion, cognitive competence and meaning making. The exploration of the Read-me-to-Resilience intervention as a protective strategy was rooted in the social-ecological perspective of resilience, which focuses on positive adjustment to adversity through resilience protective systems. Fifteen South African educators were requested to implement the Read-me-to-Resilience intervention strategy within their school context. Participation in the study was voluntary. An explorative qualitative research approach was used. Three unstructured focus-group interviews were conducted, and research diaries were kept by the participants. The educator participants reported that the indigenous African stories had promoted problem-solving and leadership skills, personal positive strengths and attachment relationships and had stimulated renewed appreciation for resources within the traditional African culture. Relevant literature on protective systems for resilience development supports my research findings. It is proposed that culturally relevant stories, as an inexpensive strategy, should be utilised within the school community to promote adaptive and preventive protective systems for at-risk learners.

Keywords: at-risk learners; indigenous stories; protective systems; resilience; school community

Introduction

Professionals serving in South African schools such as professional therapists, educators, and staff of nongovernmental organisations, among others - frequently experience burnout, trying to meet the needs of the growing number of at-risk learners (Joubert & Hay, 2020; Theron, 2016). At-risk in this context can refer to experiencing adversity (e.g., orphanhood or poverty), traumatic experiences (e.g., loss or sexual abuse) or physiological pathology (e.g., disability) or can involve cumulative hazards (e.g., social marginalisation, poverty or being orphaned) (Masten, Monn & Supkoff, 2011). Such learners may not have the resources such as parental support, finances, education and role models required to manage daily life, and may need support from professionals who are equipped to enable resilience processes (Theron, 2018). However, due to economic constraints, most schools in South Africa and other developing countries do not have the economic resources to ensure that there are full-time registered professionals for at-risk learners, resulting in the search for other inexpensive strategies to support the resilience of at-risk learners (Joubert & Hay, 2019).

Literature Review

Resilience, that is, the capacity to cope with difficult life circumstances, is promoted by protective systems in individuals and their ecology, which together foster the development of positive outcomes (Ungar, 2011). Masten and Wright (2010) agree with Ungar that resilience protective systems and processes are multifaceted and formed by cultural context. However, they suggest that some resilience supporting protective systems are similar across settings and cultures. These include "self-regulation, attachment relationships, agency and mastery motivation systems, cultural traditions and religion, cognitive competence and meaning making" (Masten & Wright, 2010:213).

Attachment relationships imply an emotional connection between individuals in support of one another. Attachment as a protective system includes at-risk learners establishing connections with supportive family members, educators, friends and community members (Cicchetti, 2010). Attachment relationships with spiritual leaders within communities can encourage cultural traditions and religion as a protective system for at-risk learners. Cultural tradition and religion include "organized belief systems, knowledge, institutional practices, and material artifacts" (Lee, 2010:644) that strengthen self-regulation in socially adaptive behaviour. This means that cultural traditions and religion are changing, dynamic and passed on from generation to generation. These could serve as protective practices, especially within the South African society that is stratified by ethnicity and race (Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012).

Agency and mastery motivation involve self-determination, self-efficacy and positive self-perception within the school context that may encourage resilient functioning of at-risk learners (Masten et al., 2011). Furthermore, cognitive competence as a protective system includes thinking capability, consideration and interpretation to solve problems, carry out tasks or achieve set goals (Masten & Wright, 2010). At-risk learners who demonstrate cognitive competence are more likely to overcome difficult circumstances by finding solutions to threatening problems and, in the process, becoming more resilient (Ungar, 2011).

Self-regulation consists of a variety of skills that form part of the cognitive abilities of at-risk learners such as reflection, planning and delaying gratification that enable the executive functions of the brain (Beltman & Mansfield, 2018). Furthermore, self-regulation as a protective system is important for the social adjustment of appropriate behavioural and emotional self-regulating skills (Masten et al., 2011). On the other hand, meaning making as a protective system means that at-risk learners can find meaning in, and make sense of, their experiences (Theron, 2016). The way that individuals make sense of their lives differs but may include optimistic belief systems that support a positive viewpoint on life and hope for the future (Joubert & Hay, 2019).

One way of promoting adaptive and preventative protective systems, as discussed above, is through asset-focused strategies such as bibliotherapeutic intervention (Rosen, 2003; Reeves, 2010). In their research in South Africa, Wood, Theron and Mayaba (2012a, 2012b) focused on the resilience-promoting potential of African indigenous stories through the Read-me-to-Resilience (Rm2R) intervention (see next section -"The Rm2R Intervention Strategy"). More recently, the Rm2R intervention, as an exemplar of a bibliotherapeutic strategy, was explored in terms of capacitating lay counsellors (Joubert & Hay, 2019). Many intervention studies have applied aspects of protective systems to encourage the resilience of learners and other groups. In many of these studies ways to improve protective systems such as better childrearing or fruitful school engagement were investigated (Masten et al., 2011). Researchers have also investigated how classroom settings can be used as intervention locations to promote resilience (Song, Doll & Marth, 2013).

However, at the time of this research, I could not find studies that reported on how resilience-promoting interventions (such as Rm2R) drew on the elementary protective systems that inform positive adjustment for at-risk learners from the perspective of educators in the South African school context. Based on the above literature review, the research conveyed in this article was directed by the research question: How do educators in the South African context perceive resilience-promoting intervention (such as Rm2R) that draws on basic protective systems for at-risk learners?

The Rm2R intervention strategy

The research reported on in this article was an addition to an earlier Rm2R intervention project. The original Rm2R project started in 2009, when 90 traditional stories were collected from community members who knew traditional indigenous stories that promoted positive coping. Using a panel of educators, researchers and a psychologist, 31 of the 90 stories were picked as likely to encourage resilience. The process was further streamlined by an interracial board of five South African psychologists ranking the 24 stories most expected to promote resilience to be included in the Rm2R project. After piloting the stories, it was found that two needed to be removed from the research as they were found to be too long for the attention span of the learners. Anecdotal findings suggested that the Rm2R intervention supported South African at-risk learners between the ages of 9 and 14 years to deal with challenges more adaptively (Wood et al., 2012b). Following the pilot, only the 22 stories that were interpreted to encourage resilience were used in this study. A summary of the stories and their resilience-promoting themes is provided in Table 1.

The aim of the original Rm2R intervention project was to determine whether these traditional African stories could encourage resilience in AIDS orphans; it was found that these stories did indeed encourage resilience in AIDS orphans (Wood et al., 2012a, 2012b). However, the research reported on here had a different emphasis, namely focusing on the reflections of South African educators on strengthening the protective and positive adaptive systems in various types of at-risk learners (not just AIDS orphans) within the school context. The research was based on the following conceptual and theoretical framework.

Theoretical Framework

The overarching theoretical framework of the study is that of positive psychology, "which focuses on the strengths of individuals and their communities and is concerned with interventions that offer buffers against adversity, nurture resilience and limit pathology" (Seligman, 2005:4). Resilience is one component of positive psychology. It is often described as doing well despite hardship or risk (Rutter, 2012). A further criterion for resilience is that a significant threat must be present, although it can also be explained within a preventative context by focusing on enhancing protective factors against foreseen or unforeseen risk (Beltman & Mansfield, 2018). Individual qualities such as self-efficacy, intellect and capability are important traits that shape resilience processes (internal resources). However, these characteristics are also formed by social influences that emerge from environmental resources (external) and from cultural, relational and community resources that work in tandem, achieving a resilient outcome (Ungar, 2013). The implication is that resilience processes are not just individually developed but also part of the social ecology: individuals reach out and the social ecological environment reciprocates and vice versa.

Ungar's (2011:1) "social ecology of resilience theory" focuses on both internal and external resources. This definition of resilience reflects Bronfenbrenner's (1979:21) "theory of child development", which postulates that development depends on the interaction of all levels of an ecosystem.

Indigenous stories seem to promote interaction and reflect on the ecological-transactional perspective of how individuals' resilience processes are influenced by their environment. Thus, the first objective of the study is to focus on the reflections of South African educators using indigenous African stories (as an external resource) to enable protective systems for at-risk learners within the school system via the Rm2R intervention. The second objective is to contribute to research on possible preventative and adaptive strategies for at-risk learners in the school context by exploring the resilience-supporting processes and protective systems of the Rm2R intervention.

Methodology

Research Approach and Design

The extent to which the Rm2R intervention could be utilised as a preventative and adaptive strategy to enable protective systems within at-risk learners was determined by exploring and interpreting educator participants' understanding and experiences of the Rm2R intervention. Therefore, an explorative qualitative research approach and design were deemed appropriate to use in this research (see Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Participant Selection and Ethics

The participants in the study were purposively selected, as this sampling method was deemed suitable for this research (see Creswell & Creswell, 2018). All of the participants were former education students who were enrolled for the honours degree in Special Needs in the Faculty of Education at a university in South Africa and, therefore, they were easily accessible. Although recruiting former students can be seen as a type of sampling bias (Nieuwenhuis, 2020), access to these former students was practically simple. The inclusion criteria were as follows: participants had to be qualified educators working at schools with challenges as defined in the introduction of this article and had to be willing to participate in the Rm2R research project.

Information letters were handed out to educators who were interested in participating in the research. Fifteen educator participants consented to participate in the research; this number of participants was deemed sufficient for the research aim (see Jemielniak & Ciesielska, 2018). All the participants were working in different public double-medium primary schools in the Gauteng province (South Africa). Seven of these schools were situated in suburban environments, and the other eight schools were in townships (informal settlement housing). Nine of the participants had between 3 and 5 years' experience in teaching, and the other six had between 10 and 15 years' experience. Eight of the participants spoke Afrikaans, three spoke Sesotho and four isiZulu. The participants were briefly trained (approximately 60 minutes) to use the Rm2R intervention in their specific schools. The training involved an explanation of how the stories needed to be told and reflected on, as well as the steps that had to be taken during the storytelling process. This was done with five to 10 learners between the ages of 9 and 12 years. The storytelling process instructions provided to the participants were as follows:

• It is better to tell than to read the story.

• Engage the participants' attention, but limit interaction with them (e.g., forming a relationship, answering questions or explaining the theme of the story).

• Instruction at the beginning of the session: "I am going to tell you a story. I want you to sit quietly and listen. We are not going to talk about the story or what it means, but when it is finished, you can think about the story if you like."

• Instruction at the end of the session: "That was today's story. I will come again (next week or a specific date) to tell you another one."

• Leave as soon as the story is complete.

• Record your thoughts, feelings, or reflections (see diary instructions) as soon as possible after having read a story.

The participants were motivated to reflect on the 22 cultural stories used in their weekly storytelling sessions and to observe and reflect on the learners to whom the stories were told during each storytelling session. Thus, the participants were motivated to reflect and to observe the learners' comments on the story, how they felt during the session and the learners' behaviour while they listened to the story. Moreover, the participants had baseline professional training (through their honours degree in learner support) in providing psychological support to learners (Van Niekerk & Hay, 2009). In training the educator participants, ethical interaction with at-risk learners identified by the school-based support team was encouraged. The following ethical considerations were underscored: avoiding harm; respecting voluntary participation; their parents' or caregivers' written consent and obtaining learners' assent; and obtaining the authorisation of the principals of the respective schools. The educator participants were also trained to keep the identity of the learner participants confidential. Furthermore, the educator participants were encouraged to use the Rm2R intervention productively and always consider the welfare of participating learners (see Strydom & Delport, 2011).

The Gauteng Department of Education gave permission that the participants could use Rm2R in their schools with small groups of learners after school hours. The project was approved by the Gauteng Department of Education and the North-West University Institutional Ethics Committee (approval number 0011-08-A2).

Data Collection Methods and Analysis Research diaries and three unstructured focus-group interviews were used to explore the experiences of the educator participants in enabling at-risk learners' protective systems through the Rm2R intervention strategy. The optimal group size of a focus group is between five and eight participants (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, 2011). I adhered to this guideline by dividing the 15 participants into three groups of not more than five participants per group. The focus-group sessions were approximately 60 minutes long and were held at a place convenient for the participants. An open-ended question was posed during the focus-group interviews to elicit the participants' views and opinions. The question was: What was your experience in telling the stories to the learners? In response to the participants' answers to the main question, follow-up questions were posed.

Clarke (2009) and Engin (2011) report that research diaries helped them to understand their participants' feelings and experiences of, and thoughts about, the phenomena they investigated. This process of observation and reflection through written accounts of what the participants had heard, seen and experienced (e.g., their problems, feelings, impressions and ideas) helped to make sense of the participants' subjective experiences of the Rm2R intervention within the South African context.

The data yielded 18 data sources in total: 15 research diaries and three data sources yielded by the focus-group interviews. The data sources were constantly compared and analysed by means of inductive content analysis (see Nieuwenhuis, 2020). Inductive content analysis implies that the data determine the emergent codes and themes instead of the researcher imposing codes and themes on the data. In this research, each data source was analysed inductively, and the themes across the different data sources were compared by using the constant comparative method (Jemielniak & Ciesielska, 2018). Using this method of analysis led to a more profound understanding of the educator participants' perspectives of the protective systems elicited from the Rm2R intervention for at-risk learners, as the data directed the set of codes. All necessary steps were taken to certify the trustworthiness of the research by following the data analysis process as described above and using the five principles of transferability, dependability, credibility, authenticity and confirmability as outlined by Nieuwenhuis (2020).

Transferability was established by providing a rich description of the data, information on the process and the participants that contributed to scientific knowledge (Jemielniak & Ciesielska, 2018). This description provides other researchers with an in-depth understanding of the transferability of the current research findings to other research situations. The dependability of the data was ensured by recording the research steps taken and keeping all the findings accruing from the process to enable replication (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Credibility was established by my prolonged engagement with the data generated, checking with the participants whether the findings were correct and following the correct data analysis processes (Nieuwenhuis, 2020). Authenticity was established by ensuring a balanced representation of all the participants' belief and perspectives in relation to the Rm2R intervention (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Lastly, confirmability relates to neutrality in the interpretation of the findings. This was ensured by me striving to stay objective and to ensure that subjective experiences and interpretations of the educator participants' experiences were not forced onto the interpretations of the participants' experiences (Jemielniak & Ciesielska, 2018).

Findings and Discussion

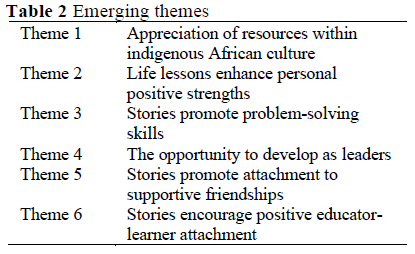

Verbatim quotations from the transcripts of the focus-group interviews and the research diaries were used to develop the themes that developed from the data. The six themes are presented in Table 2.

Theme 1: Appreciation of Resources within Indigenous African Culture

Cultural resources and traditions often encourage the resilience of individuals and add to the strength and stability of a community. Eleven of the participants in this research reported that some of the participating learners were acquainted with the stories. Other learners learnt more about African traditions (i.e. chiefs [story 11] and traditional healers [story 9]) with which they were not acquainted (see Table 1). The participants experienced the stories as encouraging learners' identification with indigenous African culture, connecting them to a collective similar cultural identity that makes them aware of empowering resources and traditions. Participant 9 wrote: "I noticed that some learners have heard these stories before but also that other learners, not knowing about their own traditions, were able to learn about their traditions and hopefully identify with their cultural roots." Participant 14 wrote in his research diary: "The learners seemed comfortable with the stories and could relate to their own culture when they heard the stories ... I think it does enhance their sense of cultural identity."

Five participants mentioned that the indigenous characters prompted remembrance for the learners that their indigenous culture and traditions offered resources that could capacitate them. In Focus-group Interview 3, Participant 11 commented:

The learners know about sangomas [in the South African context, a sangoma is a traditional healer who helps individuals to be in harmony with their cosmos in order to find meaning in adverse circumstances] and were able to recognise the value of the character in the story which relates to their own lives ... learners learn that there are tools for them to use ... this helped them to know that they have cultural roots that give them strength in difficult times.

However, four participants were of the view that some of the Sesotho- or isiZulu-speaking learners were alienated from their African traditions. Various reasons were given, including embraced Eurocentric morals succeeding urbanisation, the attainment of privileged socio-economic status and acculturation. During Focus-group Interview 2, the group agreed when Participant 8 made the following comment:

It is very difficult to assume that because the learners are black that they know the traditions of their culture. Some learners are with [sic] richer families and are exposed to Western medicine. They do not know about sangomas and witch doctors ... this causes some difficulty when we tell these stories.

The learners' absence of exposure to indigenous African figures was also confirmed in some Sesotho- or isiZulu-speaking participants' diaries. Participant 11, for example, wrote the following:

Some of the learners did not know what a sangoma was, I think it is because they were not exposed to them because they do not live in the townships [underdeveloped settlements for occupation by Black, Coloured and Indian residents] anymore. Although acculturation from informal settlements to suburban areas might have complicated the storytelling process, nine participants confirmed that the stories offered an opportunity for Sesotho-or isiZulu-speaking learners who were not familiar with indigenous African culture to acquire an identify with their traditional cultural ancestry. For example, in Focus-group Interview 2, Participant 10 stated: "It is important to understand where you come from. It helps the learners understand their past and their cultural heritage. The stories give them access to this."

The results show that the participating educators' observation that the indigenous stories stimulated a gratitude for resources within traditional African culture could reflect the worth of the intervention via the cultural traditions and religion-protective system (Masten & Wright, 2010). Indigenous stories encourage at-risk learners to be part of a group with which they associate in terms of heritage and cultural traditions. This enables awareness of their cultural traditions and provides access to resources available in cultural traditions (Theron, 2013). In the South African context, indigenous stories containing folklore, magic, myth and African traditions may be a valuable strategy to promote resilience (Lopez Levers, May & Vogel, 2011; Wood et al., 2012a).

McGee and Spencer (2012) identify the value of learners developing a cultural identity and association in which they take enjoyment and pride to excel in a society that does not always value learners from poor socio-economic backgrounds. Black learners were oppressed and marginalised during the apartheid era in South Africa. Even though the post-1994 dispensation has granted all South Africans the same human and civil rights, many Black learners in South Africa continue to be economically and socially marginalised (Lopez Levers et al., 2011). The consequence thereof is a generation of Black learners who may not appreciate their cultural customs sufficiently and need all possible support to inspire them to be proud of their heritage (Veeran & Morgan, 2009). Being socialised in indigenous African culture potentially is a supportive resource, as this worldview promotes attachment to others as part of a collective traditional belief system that offers support in challenging times. A collective cultural belief system and care from others can act as a barrier against socio-economic hardship.

Theme 2: Life Lessons Enhance Personal Positive Strengths

In this research, listening to, and learning lessons from the teachings of the indigenous stories afforded the learners the opportunity to learn life teachings that enhanced personal positive strengths. The stories encompassed implicit life lessons about how collective and personal behaviour, beliefs and attitudes form outcomes. In many of the indigenous stories, there was a life lesson and message about the importance of positive and virtuous characteristics to attain positive outcomes. The learners learnt life lessons (or life teachings) through stories that promoted characteristics such as self-assurance, being hopeful and perseverance.

Positive characteristics may enable learners to negotiate and compromise for limited or lack of resources from their environmental ecosystem. This theme was highlighted by seven of the participants during the focus-group interviews. During Focus-group Interview 1, Participant 2 commented as follows on a learner using the life lessons of the stories to gain more self-assurance:

There was a very shy child in my class, and it looks like the stories helped her in a positive way ... she was able to talk to me about the stories and started to open up in front of the class.

The participant resolved with:

... the stories might have helped the learner gain self-confidence to be less shy - when she heard the story of the ugly girl in Story 22 being able to be a leader despite being ugly ... she learnt a valuable life lesson to overcome her insecurities.

The observation that the learners learnt life teachings that encouraged positive qualities was reinforced in 12 of the participants' research diaries. In general, the participants reported that the learners had expressed compassion, persistence and hope to one another or towards the characters and circumstances in the stories. The educator participants believed that these characteristics would promote socially acceptable conduct and resilience in the learners. For instance, the participants said that the learners had learnt the life teachings in stories 1, 7 and 13 when they were able to show kindness to others. Participant 7 narrated in his research diary that "they did not like it that the buck was bullied ... they showed sympathy for the characters, I know they understand the life lessons in the stories and will not do the same [i.e. bully] to others."

Similarly, three participants described that many of the learners had predicted a virtuous conclusion while the stories were being told. In Focus-group Interview 1, Participant 4 reported: "I could see on their faces in the middle of the story that they are anticipating a good ending and they know there is a life lesson to be learnt."

The educators reported that the learners were inspired to have a hopeful outlook on the expectations associated with the stories they heard, which had a positive effect on their expectations for their own difficult lives, thus, inciting a sense of hope and anticipation that their impoverished conditions would improve. For example, Participant 15 wrote as follows:

The learners learn a lot of life lessons out of these stories and are able to learn that the story will end good [sic] ... I think it gives them hope that in their own lives it will also end good [sic] and things will work out.

The educators' experiences that the Rm2R intervention promoted the internalisation of life lessons learnt and the development of personal abilities (e.g., perseverance, self-assurance and hope) can be related with the agency and mastery motivation system and meaning-making protective systems (Cicchetti, 2010). The literature on resilience especially focuses on Black youths' agency and mastery motivation in accomplishing goals regardless of challenging circumstances, such as poverty (Theron, 2013). The participating educators also communicated being optimistic that learners' lives would become better and improve when they internalised the life lessons in the stories and expected positive results. In their South African study, Malindi and Machenjedze (2012) give an example of street youth being optimistic about their future because educators encourage them to attend school.

Theme 3: Stories Promote Problem-solving Skills Fourteen participants revealed that the learners related to how the characters were seen as role models in the stories and were able to overcome challenges that inspired the growth of the learners' problem-solving skills. Five participants noted that the learners reflected on the strategies employed by characters to address challenges, which provoked them to strengthen their own problem-solving abilities and competencies. During Focus-group Interview 3, Participant 13 commented as follows: The one learner came back to me and said to me that she can remember what I said about the story and she thought about it ... the learner said that she wanted to be like the characters in the story that can solve their own problems.

Some participants mentioned that the learners were able to emulate from the learnt problem-solving solutions demonstrated by the characters in the story. Furthermore, this was inferred from the learners' descriptions of likely solutions to challenges in the stories. This was reflected during Focus-group Interview 2, when Participant 6 said:

I tried to talk to them, but sometimes I did not need to talk to them. When you read the story, they can gather out of the story what to do in certain situations ... they have proven to me that they can solve problems for themselves by the manner in which they describe possible solutions for a scenario in the story.

Four participants stated that the learners recognised different perspectives of thinking about difficulties, and that helped them to deal with their problems. In Focus-group Interview 3, for example, Participant 15 said: "I think the stories should be told to them because it activates their minds ... this helps them to decide for themselves."

The stories not only promoted reflection and coming up with different solutions among the learners but cultivated collective problem-solving too, as seven participants reported. This related to unfamiliar characters in the story to which the learners were not accustomed and how the learners discussed and debated the physical characteristics of these characters. In Focus-group Interview 1, Participant 5 remarked: "If I did not show pictures, they started to form arguments about how the characters looked like and then they started to agree. They would say the cannibal is half human and half monster."

The educator participants said that the process of debating and reaching consensus improved the learners' problem-solving competencies and skills. Five participants voiced their self-assurance in the learners being able to solve problems in the future. This was based on the learners' understanding of likely solutions to problematic challenges in the stories. During Focus-group Interview 1, Participant 1 expressed this belief as follows:

The learners knew what were [sic] the right thing to do to resolve the problems in certain situations in the story ... they were also able to relate certain problematic situations in the stories to their own lives ... which will help them with problem-solving in the future.

According to the participating educators, the indigenous stories encouraged the development of problem-solving competencies among the learners. This occurred when the learners learnt problem-solving competencies and skills from the characters in the stories. The learners acquired different ways of thinking about challenges that supported their efforts to deal with problems. Some authors on resilience, such as Masten and Wright (2010), report that the attainment of problem-solving competencies as part of the protective systems of cognitive competence and self-regulation is related to the outcomes of constructive coping. Self-regulation and cognitive competence include having the competence to think, reflect, interpret and plan to carry out one's responsibilities or to accomplish set goals (Cicchetti, 2010). When learners demonstrate cognitive competence and self-regulation by devising solutions to threatening problems in impoverished countries, they are more likely to overcome challenging circumstances. In the process they become more resilient.

Theme 4: The Opportunity to Develop as Leaders The indigenous stories allowed the learners to emulate leadership skills with their peers. Some learners could occasionally take the lead by constructively describing the characters in the stories to other group members, as the stories were not illustrated. Participant 3 in Focus-group Interview 1 remarked on a learner's interpretation of the description of what the characters look liked in the story to his peers. According to the educator participant's description, this learner was respected in his role as the leader. Participant 3 said:

There was one boy that was clued up and took the lead. He led the group on how [sic] the monster looked like, and he said that it had big teeth. He could create a picture for the others. The others just agreed and put a name with it. He was the main brain behind it ... this motivated the others to listen later to him when he explained one of the life lessons he learnt out of the story to the other learners ... I could see that he was proud of himself that the others listened to him.

The learners who were not scared when the stories included violent characters, such as thugs or cannibals, also took the opportunity to lead in the discussions. Two participants highlighted those learners who showed courage against vicious and violent characters (stories 2, 3, 4 and 12) demonstrated bravery, resulting in the other learners admiring them. Participant 8 reported in the research diary that some of the learners were perceived as heroic and authoritative figures when they encouraged their peers to think "that the cannibals have ugly faces and the learners are not scared of the cannibals." According to the participant, the learners "all expressed their bravery especially after one or two learners said that they are not afraid of the cannibals ... the learners saw them as brave and taking the lead."

Four participants considered the possibility that the stories could motivate future leadership characteristics. They articulated how reflecting and acting as leaders while telling the stories might support learners to develop leadership skills in their personal lives and be courageous in problem-solving. For example, Participant 7 noted the following in the research diary: "Showing leadership now when I tell the story might help the learners in their own lives one day to be brave and take a leadership role against their problems."

Similarly, Participant 15 commented in the research diary that the learners visualising how they would be proactive in their community suggested that the stories stimulated lessons that might enhance leadership in the future. The participant wrote: "[T]hey had a discussion about how happy they were that Ngcede won, and they talked about what they would have done if they were the leader. They would build houses and clean the earth."

The observation that the Rm2R intervention afforded the learners the chance to act as leaders may reflect the positive influence that the intervention had on the learners. Some of the learners portrayed the characters in the stories optimistically to other learners in the group. Some learners also had possible brave responses to vicious characters (such as the cannibal) in the stories. Several of the educator participants reported that the learners talked about being future leaders in the context of their community and being able to problem-solve. To be a leader in others' , and their own, lives ensured optimism and gave agency to the learners to see the future optimistically; consequently, it was part of the "meaning-making protective system" (Masten & Wright, 2010:228). Kagan (2016) maintains that educators can act as heroes in the lives of learners by stimulating hope in the challenging circumstances often found in developing countries, which may, in turn, motivate learners to develop into heroes in their lives. Through meaningful stories, the educator participants ensured that the learners were supported to cultivate positive beliefs about themselves. Positive beliefs help learners to develop purpose and give direction about their future, which may, in turn, strengthen a positive sense of identity that would allow them to reach their goals (Meichenbaum, 2009).

Theme 5: Stories Promote Attachment to Supportive Friendships

Stories promote constructive friendships; that is, positive relationships with and positive emotions towards friends are promoted by means of stories. This theme was embodied in 13 participants' research diaries. The participants revealed that the learners accentuated the value of, and showed gratitude for, their friendships after listening to specific stories (stories 4, 5, 7 and 16) that had life lessons and themes that foregrounded the importance of constructive and supportive friendships. Participant 9 wrote that when the learners "left the class after hearing the story, they looked happy and lovingly towards their friends." Participant 4 confirmed that the learners were motivated by the stories to value their attachments to their friends: "The learners were happy that they have good friends after hearing the story.."

Moreover, Participant 14 described in the research diary that the learners voiced their opinion that "no person or animal can live without friends. " Six participants documented that the learners treasured their attachments and support to their friends, especially in challenging times. Participant 12 wrote in the research diary that, after she had told Story 5, the learners commented that "we all need good friends to be there for us in difficult times; without them, life is more difficult. " Three participants noted that the learners vowed to keep their friendships sturdy in the future. Participant 13 wrote: "The learners promised me to keep their friendships tight after I told them a story about friendships ... the learners were excited to know that there are good friends to help them in difficult times."

The educator participants' observation of the stories was that it encouraged positive and supportive friendships among their peers, as they engaged more positively with other learners after the storytelling process. Attachments with friends are recognised as a protective system and a resilience-promoting resource for learners, especially after the loss of family members (Masten & Wright, 2010). Attachment to friends encourages life skills that may help learners who exist in poor socio-economic environments and circumstances to increase their social competence behaviour and discourage risk-taking behaviour (Theron, 2018).

Theme 6: Stories Encourage Positive Educator-learner Attachment

The stories enabled the progression of a more positive interaction and relationship between the educators and their learners. Twelve participants noted more positive relationships between themselves as educators and their learners after they had told the stories to their learners. During Focus-group Interview 1, Participant 3 described how the stories enabled a trusting attachment between the participant and the learners when the stories were told. She said: "The stories enable me to spend time with them, communicate and form a trusting bond with them." During Focus-group Interview 3, Participant 15 pointed out that the trusting attachment enabled the participant to help learners in need: "I can build a trusting relationship with the learners when I tell them the stories ... they trust me and open up to me about their problems. "

In their research diaries, eight participants confirmed that their improved attachment to their learners promoted compassion. Participant 10 wrote: "The stories are a valuable method to build relationships with the learners. To care for them, understand them and to help them."

In Focus-group Interview 3, Participant 11 gave an example of how he was able to use the characters as an approach to forming a positive bond with a learner. The following is the participant's explanation:

You will use a character in the story and associate it with one of the learners. When you see the child, you will call him that character that might have been a hero in the story. When you do that, their confidence grows, and they will come to you when they have a problem.

The participating educators reflected on the Rm2R intervention as encouraging positive attachment between educator and learner. This included the development of a trusting relationship between the educators and the learners. While this theme is also part of the "attachment relationship protective system", the constructive relationship between learners and educators is reported by researchers to be one of the most significant attachments that encourage access to life-changing experiences and resilience-promoting resources. Learners and educators need to form and develop positive attachment relationships to allow learners access to a pastoral carer, a role that is fulfilled by the educator. This is especially important in developing countries like South Africa that deal with issues such as AIDS and poverty (Mampane & Bouwer, 2011).

Conclusion and Recommendations

From the six themes, it came to the fore that the participating South African educators perceived indigenous stories as having value to encourage adaptive systems among at-risk learners. These adaptive systems are echoed within the educator participants' reported findings that the indigenous African stories had promoted problem-solving and leadership skills, personal positive strengths and attachment relationships and had stimulated renewed appreciation for resources within the traditional African culture. However, traditional African stories may not be suitable for all learners because of estranged cultural heritage and various other factors within the learners' context. I recognise the limited value of such forms of intervention if they do not inspire educators to explore and investigate possible culturally relevant interventions that are applicable for their school contexts and to engage in strategies related to action research to develop their own interventions. Another limitation of this research was that the subjective data collected might have restricted the findings. However, if indigenous stories are used in an appropriate cultural context, this does not take away from the benefits such stories hold for at-risk learners. It is recommended that further research should be done on inexpensive forms of intervention such as the Rm2R. Given the urgent call for emotional support in schools for at-risk learners, inexpensive forms of intervention such as Rm2R may be a more socially just dispensation for all school communities. Similar forms of culturally appropriate intervention can also be used in other countries in need of psychosocial support in their school environments.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Prof. Linda Theron (Faculty of Humanities, Vaal Triangle Campus, North-West University when the project was executed) who facilitated the realisation of the research process detailed in this article. She was also the grant holder and principal investigator of the Read-me-to-Resilience project.

Notes

i. This article is based on the doctoral thesis of Carmen Joubert.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Beltman S & Mansfield CF 2018. Resilience in education: An introduction. In M Wosnitza, F Peixoto, S Beltman & CF Mansfield (eds). Resilience in education: Concepts, contexts and connections. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76690-4_1 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cicchetti D 2010. Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: A multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry, 9(3):145-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00297.x [ Links ]

Clarke KA 2009. Uses of a research diary: Learning reflectively, developing understanding and establishing transparency. Nurse Researcher, 17(1):68-76. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2009.10.17.1.68.c7342 [ Links ]

Creswell JW & Creswell JD 2018. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Engin M 2011. Research diary: A tool for scaffolding. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(3):296-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000308 [ Links ]

Jemielniak D & Ciesielska M 2018. Qualitative research in organization studies. In M Ciesielska & D Jemielniak (eds). Qualitative methodologies in organization studies. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Joubert C & Hay J 2019. Capacitating postgraduate education students with lay counselling competencies via the culturally appropriate bibliotherapeutic Read-me-to-Resilience intervention. South African Journal of Education, 39(3):Art. #1543, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n3a1543 [ Links ]

Joubert C & Hay J 2020. Registered psychological counsellor training at a South African faculty of education: Are we impacting educational communities? South African Journal of Education, 40(3):Art. #1840, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1840 [ Links ]

Kagan R 2016. Real life heroes life storybook (3rd ed). London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kamberelis G & Dimitriadis G 2011. Focus groups: Contingent articulations of pedagogy, politics, and inquiry. In NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Lee CD 2010. Soaring above the clouds, delving the ocean's depths: Understanding the ecologies of human learning and the challenge for educational science. Educational Researcher, 39(9):643-655. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X10392139 [ Links ]

Lopez Levers L, May M & Vogel G 2011. Research on counseling in African settings. In E Mpofu (ed). Counseling people of African ancestry. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Malindi MJ & Machenjedze N 2012. The role of school engagement in strengthening resilience among male street children. South African Journal of Psychology, 42(1):71-81. [ Links ]

Mampane R & Bouwer C 2011. The influence of township schools on the resilience of their learners. South African Journal of Education, 31(1): 114- 126. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n1a408 [ Links ]

Masten AS, Monn AR & Supkoff LM 2011. Resilience in children and adolescents. In SM Southwick, BT Litz, D Charney & MJ Friedman (eds). Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Masten AS & Wright MO 2010. Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In JW Reich, A Zautra & JS Hall (ed). Handbook of adult resilience. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

McGee E & Spencer MB 2012. Theoretical analysis of resilience and identity: An African American engineer's life story. In EJ Dixon-Román & EW Gordon (eds). Thinking comprehensively about education: Spaces of educative possibility and their implications for public policy. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meichenbaum D 2009. Bolstering resilience: Benefiting from lessons learned. In D Brom, R Pat-Horenczyk & JD Ford (eds). Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience and recovery. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J 2020. Analysing qualitative data. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Reeves T 2010. A controlled study of assisted bibliotherapy: An assisted self-help treatment for mild to moderate stress and anxiety. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(2):184-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01544.x [ Links ]

Rosen GM 2003. Bibliotherapy. In W O'Donohue, JE Fisher & SC Hayes (eds). Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Rutter M 2012. Resilience: Causal pathways and social ecology. In M Ungar (ed). The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3 [ Links ]

Seligman MEP 2005. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In CR Snyder & SJ Lopez (eds). Handbook of positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Song SY, Doll B & Marth K 2013. Classroom resilience: Practical assessment for intervention. In S Prince-Embury & DH Saklofske (eds). Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults: Translating research into practice. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4939-3 [ Links ]

Strydom H & Delport CSL 2011. Information collecting: Document study and secondary analysis. In AS de Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouché & CSL Delport (eds). Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Theron LC 2013. Black students' recollections of pathways to resilience: Lessons for school psychologists. School Psychology International, 34(5):527-539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312472762 [ Links ]

Theron LC 2016. The everyday ways that school ecologies facilitate resilience: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology International, 37(2):87-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315615937 [ Links ]

Theron LC 2018. Educator championship of resilience: Lessons from the Pathways to Resilience Study, South Africa. In M Wosnitza, F Peixoto, S Beltman & CF Mansfield (eds). Resilience in education: Concepts, contexts and connections. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76690-4_12 [ Links ]

Ungar M 2011. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1):1 -17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x [ Links ]

Ungar M 2013. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3):255-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805 [ Links ]

Van Niekerk E & Hay J (eds.) 2009. Handbook of youth counselling (2nd ed). Sandton, South Africa: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Veeran V & Morgan T 2009. Examining the role of culture in the development of resilience for youth at risk in the contested societies of South Africa and Northern Ireland. Youth and Policy, 102:53-66. Available at https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/youthandpolicy1021-1.pdf#page=56. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Wood L, Theron L & Mayaba N 2012a. Collaborative partnerships to increase resilience among AIDS orphans: Some unforeseen challenges and caveats. Africa Education Review, 9(1): 124-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2012.683631 [ Links ]

Wood L, Theron L & Mayaba N 2012b. 'Read me to resilience': Exploring the use of cultural stories to boost the positive adjustment of children orphaned by AIDS. African Journal of AIDS Research, 11(3):225-239. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2012.734982 [ Links ]

Received: 29 March 2021

Revised: 14 April 2023

Accepted: 14 August 2023

Published: 31 August 2023