Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n3a2197

ARTICLES

Social support at work and workload as predictors of satisfaction with life of Peruvian teachers

Renzo Felipe Carranza EstebanI; Oscar Mamani-BenitoII; Josué Edison Turpo ChaparroIII; Abel Apaza RomeroIV; Ronald W. Castillo-BlancoV

IGrupo de Investigación Avances en Investigación Psicológica, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Lima, Perú

IIUniversidad Nacional de San Agustín, Arequipa, Perú

IIIEscuela de Posgrado Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Perú. josuetc@upeu.edu.pe

IVFacultad de Ciencias Humanas y Educación, Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Perú

VUniversidad del Pacífico, Lima, Perú

ABSTRACT

The repercussions of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) have generated effects on the working modality of teachers, in whom it is convenient to study variables associated with well-being. The objective with this research was to determine whether social support at work and workload predict satisfaction with life in a sample of Peruvian teachers. The methodology was a predictive and cross-sectional study, carried out on 584 Peruvian teachers of both genders selected in a non-probabilistic way; to whom the social support scale at work, the workload scale and the life satisfaction scale were applied. The survey was carried out virtually, and descriptive statistics, Pearson's correlation coefficient and structural equation modelling (SEM) were conducted to examine the hypothetical model. In the analysis of the proposed model, an adequate fit was obtained, χ2 (116) = 435.5, p < .001, CFI = .963, RMSEA = .069, SRMR = .059. Thus, H1and H2 were confirmed on the positive effect of social support at work, β = .27, p < .001, and the negative effect of workload, β = -.28, p < .001 in satisfaction with life. Likewise, the t values of the beta regression coefficients of the predictor variables were highly significant (p < 0.01). It was concluded that social support at work and an adequate workload predict a better level of satisfaction with life in a sample of Peruvian teachers.

Keywords: Peruvian teachers; predictive studies; satisfaction with life; social support at work; workload

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated negative repercussions - not only in the Peruvian educational system (Pinedo-Soria & Arbitres-Flores, 2020) but also in other Latin American countries (Abreu-Hernández, León-Bórquez & García-Gutiérrez, 2020) and the rest of the world. Consequently, the ministries of health and education of all governments have seen fit to restrict the presence in classrooms in order to reduce the risk of contagion with the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Brunotto, 2020).

It is in such a context that a large number of students of different educational levels have been affected due to the closure of schools and universities. However, with the implementation of virtual classes, some authors suggest that they seemed to have more easily adapted to the change to remote education (Rizun & Strzelecki, 2020). On the other hand, basic education teachers, who, unlike those in higher education who demonstrate better attitudes towards the use of ICTs (Padilla-Beltrán, Vega-Rojas & Rincón-Caballero, 2014), experienced serious limitations in presenting their sessions due to a lack of training and little access to virtual media (Redacción Gestión, 2020).

Literature Review

Based on what has been assessed by various investigations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers appear as a population at high risk of developing psychological disorders (Dos Santos Santiago Ribeiro, Scorsolini-Comin & Dalri, 2020). Although this reality was evident before the pandemic (Cladellas-Pros, Castelló-Tarrida & Parrado-Romero, 2018), researchers such as Alves, Lopes and Precioso (2020) assert that the impact of COVID-19 has mainly reduced the perception of well-being vis-à-vis the profession, creating concern about teachers' professional future and satisfaction with life.

The available literature shows the influence that variables such as workload (Tacca & Tacca, 2019) and social support at work (Yuh & Choi, 2017) have on the satisfaction with life. Yuh and Choi (2017) conclude that receiving social support from educational administrators and co-workers generate greater job satisfaction and a better perception of quality of life in teachers. Similarly, Shahyad, Besharat, Asadi, Alipour and Miri (2011), when studying university students, concluded that there was a direct and significant effect of perceived social support on life satisfaction. This agrees with later studies in other types of populations and age groups, for example, Jung Oh, Ozkaya and LaRose (2014) who studied the relationship between these variables in the environment of social networks and Moreno-Murcia, Belando, Huéscar and Torres (2017) in the population of physically active women.

In relation to workload, studies with healthcare professionals conclude that overload affects the perception of well-being and the balance between life and work (Holland, Tham, Sheehan & Cooper, 2019). This is corroborated through other research, such as a group of organisational employees, in whom daily workload negatively predicted satisfaction with daily life (Goh, Ilies & Wilson, 2015), which is similar to Upadyaya, Vartiainen and Salmela-Aro's (2016) finding that employees who attended occupational health services showed a relationship between job exhaustion due to overload of functions and the perception of their satisfaction with life.

In the current context, Klapproth, Federkeil, Heinschke and Jungmann (2020) found that teachers in Germany who went from traditional education to distance education had worked even longer hours than special education teachers, due to technical barriers and the use of technology. Other researchers found that workload was important in explaining stress and burnout in teachers, becoming to be considered a negative psychosocial factor for the role of teachers (Tacca & Tacca, 2019).

Theoretical Framework

Satisfaction with life

Over the years, important scientific knowledge about subjective well-being has been accumulated. One of the concepts most related to this issue was satisfaction with life (De Coning, Rothmann & Stander, 2019; Gutierrez, Galiana, Tomás, Sancho & Sanchis, 2014). This construct can be defined as the positive assessment that a person makes of their own life in general and particular aspects such as health, studies, work, friends and free time (Bester, Naidoo & Botha, 2016; Schnettler, Miranda, Sepúlveda, Orellana, Denegri, Mora & Lobos, 2014).

At present it is possible to assume that those who are responsible for teaching during this health emergency have experiences that make it difficult to be positive about their lives caused by factors such as job insecurity (Mamani-Benito, Apaza Tarqui, Carranza Esteban, Rodriguez-Alarcon & Mejía, 2020) and concerns about COVID-19 (Ruiz Mamani, Morales-García, White & Marquez-Ruiz, 2020) which would negatively influence their life satisfaction (Cladellas-Pros et al., 2018; Schnettler et al., 2014). In addition there is the challenge of basic education teachers to adapt to the new virtual teaching format (Martínez-Garcés & Garcés-Fuenmayor, 2020) as very few have mastered information and communication technology (ICT) in a pedagogical sense and know how to design learning processes for virtual environments (Murillo & Duk, 2020).

Workload

Due to the labour transformation derived from changes in traditional education and the new demands of educational institutions, one of the problems that has been affecting the teaching population is the perception of work overload (Jackson & Fransman, 2018; Mafini, 2014); a situation that has already been generating negative effects on the mental health of this population, mainly affecting their quality of life (George, Louw & Badenhorst, 2008).

Workload can be defined as the interaction between the demands of the job and the capabilities of the subjects to fulfil their functions; work overload is characterised by an intense and constant physical and psychological demand that occurs in the interaction between worker and the job (Calderón-De la Cruz, Merino-Soto, Juárez-García & Jímenez-Clavijo, 2018). Along the same lines, other researchers have found that this variable was important in explaining stress and burnout in teachers, being considered as a negative psychosocial factor for the role of teachers (Dalais, Abrahams, Steyn, De Villiers, Fourie, Hill, Lambert & Draper, 2014; Mapfumo, Chitsiko & Chireshe, 2012; Tacca & Tacca, 2019).

Social support

Social support represents one of the most important resources to manage and face daily stressors within the practice of care professions, to such an extent that its absence contributes to the deterioration of health and well-being (Avendaño, Bustos, Espinoza, Garcia & Pierart, 2009; Babic, Gillis & Hansez, 2020). Therefore, social support can be defined as the perception of important help that comes from people or institutions with whom significant connections are generated in times of need, alleviating the process of facing stress (Vega Angarita & González Escobar, 2009).

In research done before the pandemic, Yuh and Choi (2017) conclude that the importance of receiving social support from educational administrators and co-workers is vital, since this generates greater job satisfaction and a better perception of the quality of life in teachers; a situation corroborated in studies with other age groups (Novoa & Barra, 2015).

Although not enough research reports on the teacher population exist to shed light on the influence of social support in online education and telework, we can infer through some studies with other types of healthcare professionals such as nurses dedicated to teaching (Dos Santos Santiago Ribeiro et al., 2020) and health personnel, that perceived social support functions as a protective factor - perceiving better social support is related to a lower probability of developing mental health diseases (Almeida, Carrer, Souzam & Pillon, 2018; Martinez-Rodríguez, Fernandez-Castillo, González-Martínez, De la C. Ávila-Hernández, Lorenzo-Carreiro & Vasquez-Morales, 2019).

Relationship between study variables

Based on what was found in the available literature and what was raised in the context of online education by the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we propose that workload and social support predict Peruvian teachers' level of satisfaction with life. This hypothesis is deduced based on the findings of Shahyad et al. (2011) who, when studying university students, concluded that there was a direct and significant effect of perceived social support on life satisfaction. This is in agreement with later studies in other types of populations and age groups, for example, Jung Oh et al.'s (2014) study on the relationship between these variables in the environment of social networks and the study by Moreno-Murcia et al. (2017) in a population of physically active women.

In relation to workload, studies with healthcare professionals conclude that overload affects the perception of well-being and the balance between life and work (Holland et al., 2019). This is corroborated by other research, such as a group of organisational employees, in whom daily workload negatively predicted satisfaction with daily life (Goh et al., 2015), which is similar to what was found by Upadyaya et al. (2016) who found that employees who attend occupational health services showed a relationship between job exhaustion due to overload of functions and the perception of their satisfaction with life.

Changing the scenario but not the topic, it is necessary to focus the discussion on the Peruvian context. Peru was greatly affected by the pandemic as a result of the high number of cases of contagion and deaths from COVID-19 - this despite being one of the first countries in Latin America to introduce compulsory social isolation measures. The need to investigate the teaching population also arises as a result of the changes brought about in traditional education, although virtual education was not a novelty since massive online courses (MOOCs) had been used for some years (Quijano-Escate, Rebatta-Acuña, Garayar-Peceros, Gutierrez-Flores & Bendezú-Quispe, 2020). The conditions of the Peruvian educational system and the added influence of the pandemic have affected teachers' satisfaction with life to an extent of showing frustration and demotivation towards presenting virtual classes (Brooks, 2020).

Hypothesis

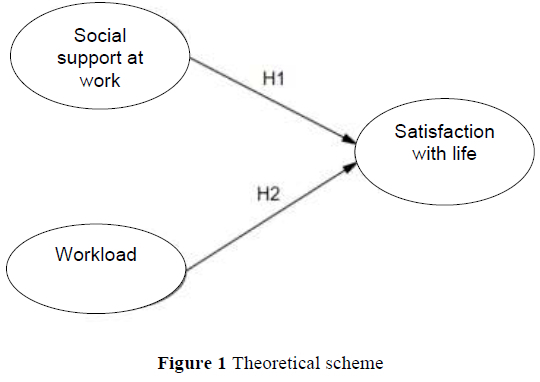

Based on what has been described, there is evidence to assume that social support at work has a positive effect on satisfaction with life (H1), likewise, workload has a negative effect on satisfaction with life (H2) (cf. Figure 1).

Objective

The objective with this research was to determine whether social support at work and workload predict satisfaction with life of a sample of Peruvian teachers.

Methodology

A predictive design and cross-sectional study was used (Ato, López & Benavente, 2013) since we explored the relationships between variables in order to predict or explain their behaviour. Satisfaction with life was the criterion variable while social support and workload were predictive variables.

Participants

Five hundred and eighty-four teachers (66.6% women and 33.4% men) selected through non-probabilistic sampling participated in the study. Of the sample, 83.2% worked at private and 16.8% at public education institutions; 47.9% of the sample taught at primary level, 36.5% at secondary level and 15.6% at the kindergarten level. The age of the participants varied between 21 and 63 years (M = 40.86; SD = 9.92).

Instruments

The scale of social support at work (EAST) (Gil-Monte, 2016) is a brief measure that assesses the social support perceived by superiors, colleagues and leaders of an organisation through emotional support. It is made up of six items that are scored based on Likert-type response options, from 0 (rarely) to 4 (every day). In our investigation the value of Cronbach' s alpha coefficient to estimate reliability was good (α = .82 [95% CI: .77-.85]).

The workload scale ([Escala de Carga de Trabajo, ECT] Calderón-De la Cruz et al., 2018) explores employees' perceptions of self-efficacy by assessing their ability to cope with work difficulties. The questionnaire is made up of six items using a Likert-type rating scale, in which there are seven response options from 0 (never) to 6 (always). The reliability of ECT in our study was α = .96 (95% CI: .95-.96).

The satisfaction with life scale ([SWLS] Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985) adapted to the Peruvian context by Caycho-Rodríguez, Ventura-León, García Cadena, Barboza-Palomino, Arias Gallegos, Dominguez-Vergara, Azabache-Alvarado, Cabrera-Orosco and Samaniego Pinho (2018) is a brief measure made up of five items that assess the level of satisfaction that a person shows with their life. The scale uses a Likert-type scale with five response options from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The reliability of the SWLS in this investigation was α = .76 (95% CI: .72-.78).

Process

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión. Subsequently, due to restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, a virtual format of the questionnaire was created through Google Forms. The questionnaire contained questions related to the characteristics of the participants and the items of the instruments used in the study. The form was sent to the coordinators of the participating institutions who redirected the forms to the kindergarten, elementary and secondary teachers through their institutional platforms. In addition, before accessing the questionnaire through the link, the participants gave informed consent to participate in the study. The participants were also informed about the objectives of the study, that participation was voluntary and anonymous, that the use of the data would be confidential, that there was no risk of participation and that they could withdraw from the study without penalty at any time. Only teachers who agreed to participate and who gave informed consent responded to the questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

In the first step, the mean, asymmetry, kurtosis and standard deviation of the study variables (satisfaction with life, social support at work and workload) were calculated. In the second step, the t-test was used on independent samples to determine whether significant differences existed in the scores of the variables between men and women. In the third step, a Pearson correlation analysis and a multivariate linear regression analysis were performed between the variables social support, workload and satisfaction with life. Finally, the study model was analysed by SEM with the diagonally weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator, which is recommended for ordinal variables (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006; Gana & Broc, 2019). Fit assessment was performed with the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardised residual root mean square (SRMR). The values of CFI > .90 (Bentler, 1990), RMSEA < .080 and SRMR < .080 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992) were used. For the reliability analysis, the alpha internal consistency method (α) was used. The data analysis was performed with version 4.0.5 of R software (R Development Core Team, 2007) and version 0.6-9 of the lavaan library (Rosseel, 2012).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The scores of the variables analysed were scaled to values between 0 and 30 to facilitate their visualisation considering that this process does not affect the values of the correlations between the constructs. Table 1 shows the descriptive results such as asymmetry (A) and the correlation results found between r = -.08 and r = .99 for the study variables. In addition, Table 1 also shows the alpha internal consistency coefficients, which were found to be between the values of .81 and .88.

Differences between Satisfaction with Life, Social Support at Work and Workload Based on the results of the comparison of means, it is assumed that there are no significant differences in satisfaction with life, social support at work and workload between men and women (t = 1.3519, p = 0.117; t = 1.926, p = 0.055; t = .300, p = 0.764) (Table 2).

Life Satisfaction Prediction

In the analysis of the proposed model, an adequate fit was obtained, χ2 (116) = 435.5, p < .001, CFI = .963, RMSEA = .069, SRMR = .059. Thus, H1 and H2 were confirmed; on the positive effect of social support at work, β = .27, p < .001, and the negative effect of workload, β = -.28, p < .001 on the satisfaction with life (cf. Figure 2).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a massive increase in research, not only in clinical (Brunotto, 2020) and labour (Wullur & Werang, 2020) spheres but also in educational (Klapproth et al., 2020) aspects. Some experts, for example, analysed the role of artificial intelligence as a mitigator of work overload in basic education teachers (Perks, 2020). In Latin America, direct correlations were observed between stress due to organisational conditions and psychosocial factors (Alvites-Huamaní, 2019); data showed that teachers were of the opinion that working conditions affected their quality of life. In Peru, the situation became more aggravating as a result of the constant declarations of emergency which directly affected teachers in basic, secondary and university education (Brooks, 2020; Mamani-Benito et al., 2020), where male teachers had already shown high levels of emotional exhaustion even before the COVID-19 pandemic (Tacca & Tacca, 2019).

The objective of this research was to determine whether social support at work and workload predicted satisfaction with life of a sample of Peruvian teachers. The results indicate that there were no significant differences between the scores of men and women in relation to the variables satisfaction with life, social support at work, and workload (p > 0.05). This means that both genders perceived these variables in a similar way. This result is different from Tacca and Tacca (2019) who observed greater emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation in men. It also differs from mental health studies that highlight the differences between men and women in relation to working life (Dos Santos Santiago Ribeiro et al., 2020). Murniarti, Sihotang and Rangka (2020) reported that male teachers had better skills than women in making decisions about the improvement of personal life, and that social support protects more against negative results in women (Yuh & Choi, 2017). Previous studies highlight that the academic life of women has decreased considerably due to work overload and domestic work overload (Jackson & Fransman, 2018), and that they need to prepare for classes when their children are asleep (Rizun & Strzelecki, 2020).

Correlation analyses between satisfaction with life and social support show a direct and significant correlation (p < .01). This means that teachers who experience high levels of social support also show better levels of satisfaction with life. Novoa and Barra (2015) observe that social support shows a greater relationship with satisfaction with life than other variables in a sample of 353 people. Similarly, Biccheri, Roussiau and Mambet-Doué (2016) analysed 590 people and found that social support varied positively with the level of satisfaction with life. In another study with 280 teachers in Korea, it was shown that social support was related to quality of life and job satisfaction, considering that work represents an important part of teachers' lives and their evaluation of life in general (Yuh & Choi, 2017). In an extensive study of literature on exhaustion, Shaufeli and Enzmann (1998) observed that emotional exhaustion was affected by a lack of social support, which affected satisfaction with life because social support reduces negative emotions and facilitates better levels of satisfaction with life and work (Alvites-Huamaní, 2019; Murniarti et al., 2020; Park, Roh & Yeo, 2012).

In the case of workload and satisfaction with life, an inverse relationship was found, indicating that the workload experienced by teachers had a direct relationship with life satisfaction. Teachers with a higher workload experienced chronic tension and sleep problems (Babic et al., 2020; Huyghebaert, Gillet, Beltou, Tellier & Fouquereau, 2018) which in turn significantly predicted their satisfaction with life in the negative direction (Çelik & Kahraman, 2018). Tacca and Tacca (2019) confirm that workload causes stress and manifests itself in exhaustion, anxiety, and lack of sleep, which affects satisfaction with life. This situation worsened in the context of COVID-19. Forcing teachers to work remotely and virtually (Alves et al., 2020; Dos Santos Santiago Ribeiro et al., 2020), the technological adaptation of both teachers and students (Iivari, Sharma & Ventä-Olkkonen, 2020; Osman, 2020) coupled with isolation and social distancing, generated greater teacher workload (Gonzalez, De la Rubia, Hincz, Comas-Lopez, Subirats, Fort & Sacha, 2020). Similar studies reveal that digital transformation experienced by teachers, maintaining the school schedule and structure at a synchronous online level, online classes, job reviews and all kinds of changes had increased their workload (Iivari et al., 2020). The effects of work overload were associated with work-family conflicts, mental fatigue and physical and psychological symptoms negatively impacting teachers' attitudes and behaviour (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). Various studies show that the administrative workload added to teachers' already heavy workload compromises their main activity, which is teaching (Kim, 2019; Liu, 2019). A similar result was found in a sample of 94 Papua teachers, which showed a direct relationship between workload and emotional exhaustion (Werang, 2018). Finally, Kariková and Valent (2020) found that success at work allows for a positive assessment of life, which increased satisfaction with life of Slovak teachers.

The predictive power of workload on life satisfaction is relevant (β = -.28; Ferguson, 2009); teachers with high workload scores obtain lower scores on the satisfaction index with life, which is understood as a measure based on perception and assessment of one's own life (Diener et al., 1985).

These findings correlate with Nastasa, Golu, Buruiana and Oprea (2021) who found that work overload had a negative influence on satisfaction with life and studies. For their part, Mérida-López and Extremera (2020) found that positive work associations increased levels of satisfaction with life. The literature reviewed emphasises precisely those negative associations between conflict-work and family-work (De Simone, Lampis, Lasio, Serri, Cicotto & Putzu, 2014; Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo & Mansfield, 2012). This implies that it is necessary for the education system to mitigate the unfavourable impact of the workload on teachers' satisfaction, therefore, it is necessary for the school management to adopt measures to increase social support and guarantee an optimal workload for teachers (Nastasa et al., 2021).

From the results discussed above, it can be inferred that teachers who have high levels of social support at work have a higher satisfaction with life. This is consistent with the findings of Schnettler et al. (2014) who found that social support moderates changes in life satisfaction -especially in traumatic times. Based on the findings of Meng (2022) there is a strong relationship between the work context and satisfaction with life. The workload variable has an inverse and significant relationship, which suggests that teachers who are weighed down by work overload perceive their level of satisfaction with life to be lower than it is. A similar result was also reported by Klapproth et al. (2020) who found that more than half of all teachers who spent more than 4 hours a day teaching experienced higher levels of stress.

Our study was not without limitations. One of the main limitations has to do with the fact that the sample was made up of a high proportion of religious participants, so it is not representative of the entire Peruvian teaching population. For this reason, new research is necessary with representative samples in different areas and contexts in the country. Another limitation was related to the cross-sectional study, which does not allow one to establish causality inferences.

Conclusion

It is concluded that a reasonable workload and the social support provided at work predict a better level of satisfaction with life in a sample of Peruvian teachers. This result does not vary by gender, therefore, the implications is that the study informs the understanding and response to the COVID-19 pandemic in an educational context.

Authors' Contributions

RFCE and JETCH conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analysed and interpreted the data. OMB, AAR and RWCB contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools or data. All authors contributed to the writing of the article and approved the submitted version.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abreu-Hernández LF, León-Bórquez R & García-Gutiérrez JF 2020. Pandemia de COVID-19 y educación médica en Latinoamérica [COVID-19 pandemic and medical education in Latin America]. FEM: Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica, 23(5):237-242. https://doi.org/10.33588/fem.235.1088 [ Links ]

Almeida LY, Carrer MO, Souzam J & Pillon SC 2018. Avaliação do apoio social e estresse em estudantes de enfermagem [Evaluation of social support and stress in nursing students]. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem, 52:e03405. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2017045703405 [ Links ]

Alves R, Lopes T & Precioso J 2020. Teachers' well-being in times of Covid-19 pandemic: Factors that explain professional well-being. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 15:203-217. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.5120 [ Links ]

Alvites-Huamaní CG 2019. Estrés docente y factores psicosociales en docentes de Latinoamérica, Norteamérica y Europa [Teacher stress and psychosocial factors in teachers from Latin America, North America and Europe]. Propositos y Representaciones, 7(3):141-178. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2019.v7n3.393 [ Links ]

Ato M, López JJ & Benavente A 2013. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología [A classification system for research designs in psychology]. Anales de Psicología, 29(3):1038-1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511 [ Links ]

Avendaño C, Bustos P, Espinoza P, Garcia F & Pierart T 2009. Burnout y apoyo social en personal del servicio de psiquiatría de un hospital público [Burnout and social support staff of a public hospital psychiatry]. Ciencia y Enfermeria, 15(2):55-68. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95532009000200007 [ Links ]

Babic A, Gillis N & Hansez I 2020. Work-to-family interface and well-being: The role of workload, emotional load, support and recognition from supervisors. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46:a1628. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1628 [ Links ]

Beauducel A & Herzberg PY 2006. On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 13(2):186-203. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2 [ Links ]

Bentler PM 1990. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2):238-246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [ Links ]

Bester E, Naidoo P & Botha A 2016. The role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(2):245-266. https://doi.org/10.15270/52-2-503 [ Links ]

Biccheri E, Roussiau N & Mambet-Doué C 2016. Fibromyalgia, spirituality, coping and quality of life. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4):1189-1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0216-9 [ Links ]

Brooks D 2020. Clases en Zoom: 4 problemas de la enseñanza en línea que señala el profesor que anunció su renuncia a sus alumnos en directo [Classes on Zoom: 4 problems of online teaching pointed out by the teacher who announced his resignation to his students live]. BBC, 11 November. Available at https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-54787845. Accessed 15 November 2020. [ Links ]

Browne MW & Cudeck R 1992. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2):230-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005 [ Links ]

Brunotto M 2020. La ciencia en tiempos de pandemia [Science in times of pandemic]. Revista de La Facultad de Odontología, 30(1):1-2. https://doi.org/10.25014/revfacodont271.2020.30.1.1 [ Links ]

Calderón-De la Cruz GA, Merino-Soto C, Juárez-García A & Jimenez-Clavijo M 2018. Validación de la Escala de Carga de Trabajo en trabajadores peruanos [Validation of Workload Scale in Peruvian workers]. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales, 21(3):123-127. https://doi.org/10.12961/aprl.2018.21.03.2 [ Links ]

Caycho-Rodríguez T, Ventura-León J, García Cadena CH, Barboza-Palomino M, Arias Gallegos WL, Dominguez-Vergara J, Azabache-Alvarado K, Cabrera-Orosco I & Samaniego Pinho A 2018. Psychometric evidence of the Diener's Satisfaction with Life Scale in Peruvian elderly. Revista Ciencias de La Salud, 16(3):473-491. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/revsalud/a.7267 [ Links ]

Çelik OT & Kahraman Ü 2018. The relationship among teachers' general self-efficacy perceptions, job burnout and life satisfaction. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(12):2721 -2729. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.061204 [ Links ]

Cladellas-Pros R, Castelló-Tarrida A & Parrado-Romero E 2018. Satisfacción, salud y estrés laboral del profesorado universitario según su situación contractual [Satisfaction, health and work-related stress of the university professorship according to their contractual status]. Revista de Salud Pública, 20(1):53-59. https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.v20n1.53569 [ Links ]

Dalais L, Abrahams Z, Steyn NP, De Villiers A, Fourie JM, Hill J, Lambert EV & Draper CE 2014. The association between nutrition and physical activity knowledge and weight status of primary school educators. South African Journal of Education, 34(3):Art. # 817, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201409161057 [ Links ]

De Coning JA, Rothmann S & Stander MW 2019. Do wage and wage satisfaction compensate for the effects of a dissatisfying job on life satisfaction? SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 45:a1552. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1552 [ Links ]

De Simone S, Lampis J, Lasio D, Serri F, Cicotto G & Putzu D 2014. Influences of work-family interface on job and life satisfaction. Applied Research Quality Life, 9:831-861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9272-4 [ Links ]

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ & Griffin S 1985. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1):71 -75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [ Links ]

Dos Santos Santiago Ribeiro BM, Scorsolini-Comin F & Dalri RCMB 2020. Ser docente en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19: Reflexiones sobre la salud mental [Being a professor in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections on mental health]. Index de Enfermeria, 29(3):137-141. [ Links ]

Erdogan B, Bauer TN, Truxillo DM & Mansfield LR 2012. Whistle while you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38(4):1038-1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429379 [ Links ]

Ferguson CJ 2009. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5):532-538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808 [ Links ]

Gana K & Broc G 2019. Structural equation modeling with lavaan. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

George E, Louw D & Badenhorst G 2008. Job satisfaction among urban secondary-school teachers in Namibia. South African Journal of Education, 28(2):135-154. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v28n2a127 [ Links ]

Gil-Monte PR 2016. The UNIPSICO questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the scales measuring psychosocial demands. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales, 19(2):86-94. https://doi.org/10.12961 /aprl.2016.19.02.2 [ Links ]

Goh Z, Ilies R & Wilson KS 2015. Supportive supervisors improve employees' daily lives: The role supervisors play in the impact of daily workload on life satisfaction via work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89:65-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.04.009 [ Links ]

Gonzalez T, De la Rubia MA, Hincz KP, Comas-Lopez M, Subirats L, Fort S & Sacha GM 2020. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students' performance in higher education. PLoS ONE, 15(10):e0239490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239490 [ Links ]

Gutierrez M, Galiana L, Tomás JM, Sancho P & Sanchis E 2014. La predicción de la satisfacción con la vida en personas mayores de Angola: El efecto moderador del género [Predicting life satisfaction in Angolan elderly: The moderating effect of gender]. Psychosocial Intervention, 23(1):17-23. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2014a2 [ Links ]

Holland P, Tham TL, Sheehan C & Cooper B 2019. The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Applied Nursing Research, 49:70-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.06.001 [ Links ]

Huyghebaert T, Gillet N, Beltou N, Tellier F & Fouquereau E 2018. Effects of workload on teachers' functioning : A moderated mediation model including sleeping problems and overcommitment. Stress & Health, 34(5):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2820 [ Links ]

Iivari N, Sharma S & Ventä-Olkkonen L 2020. Digital transformation of everyday life - How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 55:102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183 [ Links ]

Jackson LTB & Fransman EI 2018. Flexi work, financial well-being, work-life balance and their effects on subjective experiences of productivity and job satisfaction of females in an institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1):a1487. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1487 [ Links ]

Jung Oh H, Ozkaya E & LaRose R 2014. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 30:69-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/jxhb.2013.07.053 [ Links ]

Kariková S & Valent M 2020. Life satisfaction of Slovak teachers. The New Educational Review, 59:13-23. https://doi.org/10.15804/tner.20.59.L01 [ Links ]

Kim KN 2019. Teachers' administrative workload crowding out instructional activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 39(1):31-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1572592 [ Links ]

Klapproth F, Federkeil L, Heinschke F & Jungmann T 2020. Teachers' experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(4):444-452. https://doi.org/10.33902/jpr.2020062805 [ Links ]

Liu M 2019. How does teachers' workload affect their utilization of information and communication technology: Research results by cluster analysis on primary and secondary teachers in China. In A Benn, M Cerna, HY Yang & S Yu (eds). Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET). Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISET.2019.00029 [ Links ]

Mafini C 2014. Tracking the employee satisfaction-life satisfaction binary: The case of South African academics. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(2):Art. #1181, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v40i2.1181 [ Links ]

Mamani-Benito O, Apaza Tarqui EE, Carranza Esteban RF, Rodriguez-Alarcon JF & Mejía CR 2020. Inseguridad laboral en el empleo percibida ante el impacto del COVID-19 : Validación de un instrumento en trabajadores peruanos (LABOR-PE-COVID-19) [Perceived job insecurity in employment due to the impact of COVID-19: Validation of an instrument on Peruvian workers (LABOR-PE-COVID-19)]. Revista de la Asociación Española de Especialistas en Medicina del Trabajo, 29(3):184-193. Available at https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/medtra/v29n3/1132-6255-medtra-29-03-184.pdf. Accessed 9 November 2020. [ Links ]

Mapfumo JS, Chitsiko N & Chireshe R 2012. Teaching Practice generated stressors and coping mechanisms among student teachers in Zimbabwe. South African Journal of Education, 32(2): 155-166. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n2a601 [ Links ]

Martínez-Garcés J & Garcés-Fuenmayor J 2020. Competencias digitales docentes y el reto de la educación virtual derivado de la covid-19 [Digital teaching skills and the challenge posed by virtual education as a result of Covid-19]. Educación y Humanismo, 22(39): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.17081/eduhum.22.39.4114 [ Links ]

Martinez-Rodríguez L, Fernandez-Castillo E, González-Martínez E, De la C. Ávila-Hernández Y, Lorenzo-Carreiro A & Vasquez-Morales HL 2019. Apoyo social y resiliencia: Factores protectores en cuidadores principales de pacientes en hemodiálisis [Social support and resilience: Protective factors in primary caregivers of patients on hemodialysis]. Enfermería Nefrológica, 22(2):130-139. https://doi.org/10.4321/s2254-28842019000200004 [ Links ]

Meng Q 2022. Chinese university teachers' job and life satisfaction : Examining the roles of basic psychological needs satisfaction and self-efficacy. The Journal of General Psychology, 149(3):327-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2020.1853503 [ Links ]

Mérida-López S & Extremera N 2020. The interplay of emotional intelligence abilities and work engagement on job and life satisfaction : Which emotional abilities matter most for secondary-school teachers ? Frontiers in Psychology, 11:563634. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563634 [ Links ]

Moreno-Murcia JA, Belando N, Huéscar E & Torres MD 2017. Apoyo social, ejercicio físico y satisfacción con la vida en mujeres [Social support, physical exercise and life satisfaction in women]. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 49(3):194-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2016.08.002 [ Links ]

Murillo FJ & Duk C 2020. El Covid-19 y las brechas educativas [Editorial: The Covid-19 and the educational gaps]. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 14(1):11 -13. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-73782020000100011 [ Links ]

Murniarti E, Sihotang H & Rangka IB 2020. Life satisfaction and self-development initiatives among honorary teachers in primary schools. Ilkogretim Online - Elementary Education Online, 19(04):2571-2586. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2020.19.04.002 [ Links ]

Nastasa M, Golu F, Buruiana D & Oprea B 2021. Teachers' work-home interaction and satisfaction with life : The moderating role of core self-evaluations life. Educational Psychology, 41(6):806-820. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1852182 [ Links ]

Novoa C & Barra E 2015. Influencia del apoyo social percibido y los factores de personalidad en la satisfacción vital de estudiantes universitarios [Influence of perceived social support and personality factors in vital satisfaction of university students]. Terapia Psicológica, 33(3):239-245. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082015000300007 [ Links ]

Osman ME 2020. Global impact of COVID-19 on education systems: The emergency remote teaching at Sultan Qaboos University. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4):463-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1802583 [ Links ]

Padilla-Beltrán JE, Vega-Rojas PL & Rincón-Caballero DA 2014. Tendencias y dificultades para el uso de las TIC en educación superior [Tendencies and difficulties associated with the use of ICTs in higher education]. Entramado, 10(1):272-295. Available at https://revistas.unilibre.edu.co/index.php/entramado/article/view/3493. Accessed 16 October 2020. [ Links ]

Park J, Roh S & Yeo Y 2012. Religiosity, social support, and life satisfaction among elderly Korean immigrants. The Gerontologist, 52(5):641-649. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr103 [ Links ]

Perks S 2020. AI could reduce teacher workload. Physics World, 33(8):11. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-7058/33/8/15 [ Links ]

Pinedo-Soria A & Arbitres-Flores L 2020. Educación médica virtual en Perú en tiempos de COVID-19 [Virtual medical education in peru during COVID-19]. Revista de la Facultad Medicina Humana, 20(3):536-537. https://doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v20i3.2985 [ Links ]

Quijano-Escate R, Rebatta-Acuña A, Garayar-Peceros H, Gutierrez-Flores KE & Bendezú-Quispe G 2020. Aprendizaje en tiempos de aislamiento social: Cursos masivos abiertos en línea sobre la COVID-19 [Learning in times of social isolation: Massive open online courses on COVID-19]. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 37(2):375-377. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.372.5478 [ Links ]

R Development Core Team 2007. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [ Links ] Redacción Gestión 2020. Aprendo en Casa: Contratarán internet a profesores de educación básica para que dicten clases virtuales [I learn at home: They will hire basic education teachers to teach virtual classes]. Gestión, 10 September. Available at https://gestion.pe/peru/coronavirus-peru-aprendo-en-casa-contrataran-internet-a-profesores-de-educacion-basica-para-que-dicten-clases-virtuales-minedu-nndc-noticia/. Accessed 25 November 2020. [ Links ]

Rizun M & Strzelecki A 2020. Students' acceptance of the COVID-19 impact on shifting higher education to distance learning in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18):6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186468 [ Links ]

Rosseel Y 2012. lavaan : An R Package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2):1-36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [ Links ]

Ruiz Mamani PG, Morales-García WC, White M & Marquez-Ruiz MS 2020. Propiedades de una escala de preocupación por la COVID-19: Análisis exploratorio en una muestra peruana [Properties of a scale of concern for COVID-19: Exploratory analysis in a Peruvian sample]. Medicina Clínica, 155(12):535-537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.06.022 [ Links ]

Shahyad S, Besharat MA, Asadi M, Alipour AS & Miri M 2011. The Relation of Attachment and perceived social support with Life Satisfaction: Structural Equation Model. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Science, 15:952-956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.219 [ Links ]

Schnettler B, Miranda H, Sepúlveda J, Orellana L, Denegri M, Mora M & Lobos G 2014. Variables que influyen en la satisfacción con la vida de personas de distinto nivel socioeconómico en el sur de Chile [Variables affecting satisfaction with life in people from different socioeconomic groups in southern Chile]. Suma Psicologica, 21(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0121-4381(14)70007-4 [ Links ]

Tacca DR & Tacca AL 2019. Sindrome de Burnout y resiliencia en profesores peruanos [Burnout syndrome and resilience in Peruvian teachers]. Revista de Investigación Psicológica, 22:11 -30. Available at http://www.scielo.org.bo/pdf/rip/n22/n22_a03. Accessed 16 November 2020. [ Links ]

Upadyaya K, Vartiainen M & Salmela-Aro K 2016. From job demands and resources to work engagement, burnout, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and occupational health. Burnout Research, 3(4):101-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.10.001 [ Links ]

Vega Angarita OM & González Escobar DS 2009. Apoyo social: Elemento clave en el afrontamiento de la enfermedad crónica [Social support key element in confronting chronic illness]. Enfermeria Global, 16:1-11. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.8.2.66351 [ Links ]

Werang BR 2018. Pengaruh beban kerja, karakteristik individu, dan iklim sekolah terhadap kelelahan emosional guru sd di Papua [The effect of workload, individual characteristics, and school climate on teachers' emotional exhaustion in elementary schools of Papua]. Jurnal Cakrawala Pendidikan, 37(3):457-469. https://doi.org/10.21831/cp.v38i3.20635 [ Links ]

Wullur MM & Werang BR 2020. Emotional exhaustion and organizational commitment: Primary school teachers' perspective. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(4):912-919. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i4.20727 [ Links ]

Yuh J & Choi S 2017. Sources of social support, job satisfaction, and quality of life among childcare teachers. The Social Science Journal, 54(4):450-457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.08.002 [ Links ]

Received: 24 February 2021

Revised: 4 May 2022

Accepted: 13 December 2022

Published: 31 August 2023