Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 no.3 Pretoria Ago. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n3a2168

ARTICLES

More than a principal: Ubuntu at the heart of successful school leadership in the Western Cape

Michael Kramer

Department of Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. michaelkramersa@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

School leadership matters. After teachers and teaching, school leadership is the most important determinant of learner achievement in school. Despite this, there is still uncertainty regarding what successful school leadership is and what successful school leaders do in non-Western contexts. In this mixed methods study I explored successful high school leadership in South Africa. Specifically, a questionnaire was administered to 38 principals from academically high-achieving schools from a range of socioeconomic contexts throughout the Western Cape, and 14 principals were interviewed. An integrated analysis reveals the paradox of uniqueness and universality of successful school leadership in South Africa, outlining that while there is no single best approach, various similarities exist between successful school leaders and established international literature. I found that successful principals adapt to their context, amalgamate transformational, instructional and distributed leadership styles, set direction, develop people, constantly realign the school with teaching and learning, and, importantly, strive to make a difference in the lives of others. It is about leading with Ubuntu. By highlighting these characteristics and practices, I offer theoretical, practical and personal advice to current and aspiring school leaders, academics and policy makers.

Keywords: mixed methods; principal leadership; school leadership; South Africa; ubuntu

Introduction

International research consistently demonstrates the impacts of school leadership, especially principal leadership, on learners' learning, through the quality of teaching and learning, school culture and structure of the organisation (Marks & Printy, 2003; Mulford, 2008). While school leaders create the conditions which allow others to perform in ways that they otherwise would not have been able to (Robinson, Hohepa & Lloyd, 2009), debate still exists as to what strategies and practices successful school leaders employ to positively influence learners' learning (Castillo & Hallinger, 2018), emphasising that "much is left to be known regarding the impact of school principals on student [learner] achievement" (Nettles & Herrington, 2007:724).

We know that successful school leaders integrate a range of styles of leadership, adopt core practices, and their broad, demanding role includes managerial aspects (Day, Gu & Sammons, 2016; Leithwood, Seashore Louis, Anderson & Wahlstrom, 2004). However, there is still an overreliance on research based in Western contexts with a relatively small sample (Dimmock & Walker, 2000; Mertkan, Arsan, Cavlan & Aliusta, 2017). There is a need for more nuanced, contextualised understanding of successful school leadership, particularly in South Africa, where poor leadership plagues the schooling system (Jansen, 2016).

With this study I aimed to examine the South African perspective of successful school leadership and explore whether this is consistent with, or challenges, international literature. I hope to cast light on successful principals' professional and personal characteristics and practices, which could be useful for aspiring South African school leaders, researchers and policy makers.

Contextual Positioning of the Study

South Africa is a complex country with its educational organisations described as "a cocktail of first and third world institutions" (Chikoko, Naicker & Mthiyane, 2015:452). Although apartheid officially ended in 1994, it did not mark the end of discriminatory inequality in South African schools, especially those in townships (Mawdsley, Bipath & Mawdsley, 2014). South Africa has achieved near universal access for the compulsory 9 years of schooling (Motala, Dieltiens & Sayed, 2009), however, according to The World Bank (2020), it is the most unequal country in the world. This inequality is apparent in every aspect of life and is reflected through high unemployment, low literacy rates and high levels of crime (Cramm, Nieboer, Finkenflügel & Lorenzo, 2013), which disproportionately affect people of colour (Leibbrandt, Finn & Woolard, 2012).

The majority of children in the South African education system attend school but do not learn and are ill-prepared for the world thereafter (Gilmour & Soudien, 2009; Roodt, 2018). Spaull (2019) reports that of 100 children who started Grade 1 in 2007, disturbingly only 51 made it to Grade 12, 40 passed and a mere 17 achieved the results eligible for university. Worryingly, this is not a new trend, nor isolated to Grade 12 results. In 2003, the Western Cape Education Department ([WCED], 2005) reported that only 37% of Grade 3 learners passed a numeracy test. In Grade 9, the gap between the poorest and the wealthiest learners is approximately 5 years' worth of learning (Zoch, 2017). These vast inequalities heighten the prominence of school leadership, as leaders in schools in challenging circumstances have an enhanced impact (Harris, Chapman, Muijs, Russ & Stoll, 2006; Leithwood et al., 2004). South Africa's Department of Education (2008) is aware of this and has created a number of initiatives to empower school leaders, such as the Advanced Certificate in Education (Bush, Kiggundu & Moorosi, 2011).

School Leadership and Ubuntu

School leadership strategies have been classified into different types, styles or models. While transformational (Hallinger, 2003; Leithwood & Jantzi, 2005) and instructional leadership (O'Donnell & White, 2005) have been the most thoroughly researched (Day et al., 2016), other studies focused on distributed (Spillane, 2006), collegial (Sweetland & Hoy, 2000), and democratic leadership (Muijs, Harris, Chapman, Stoll & Russ, 2004). In a review of literature pertaining to school leadership in South Africa, Bush and Glover (2016) identified 10 types of leadership, however only three, transformational, instructional and distributed leadership, carried importance.

Dichotomising leadership types is not always useful, as "there is no single leadership formula for achieving success" (Day et al., 2016:253). Successful principals combine a range of leadership strategies according to the phase of development of the school (Day, 2015; Day et al., 2016). This depends on the principal's diagnosis of the contextual needs of the learners, staff and general school community, thus implementing a "fit-for-purpose" approach (Day et al., 2016:225).

Maphalala (2017) demonstrates how Ubuntu, I am because you are (Mbigi, 2000), encourages team work in a school leadership setting through three pillars: intrapersonal values, interpersonal values and contextual values. For example, intrapersonal values can include passion, resilience, moral and ethical principles, while interpersonal values relate to the ability to work with others, trust others and have empathy for others. Contextual values refer to the extent of the influence of the surroundings. Using this framework, and building on the work by Msila (2008, 2010), I followed an integrated model of school leadership with Ubuntu at its heart (Printy, Marks & Bowers, 2009).

Methodology

Social inquiry cannot advance without a mix of perspectives (Pearce, 2015). Mixed methods allow researchers to "encapsulate quantitative variables with phenomena that cannot easily be quantified in the same project" (Morse, 2010:339). Mixed methods provide the research equivalent of the equation 1 + 1 = 3. That is, the whole is greater than the sum of the individual components (Fetters & Freshwater, 2015). Or simply, the strengths of one approach make up for the weaknesses of the other (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017). Given that only 12% of South African Education Leadership and Management empirical research follows a mixed methods approach and often include small samples (Hallinger, 2019), opportunities exist to generate more comprehensive findings and meaningful conclusions by conducting a larger, mixed methods study.

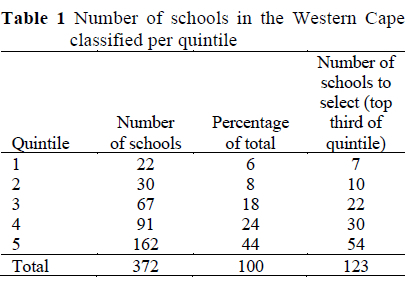

While other studies selected high achieving schools (Day et al., 2016; Taylor, Wills & Hoadley, 2019), in South Africa this would generate a sample highly skewed by affluence. Thus, inspired by Wills (2017), schools that performed in the top third of their respective quintiles, based on the 2019 National Senior Certificate (NSC) results, were selected to form part of the study. Table 1, outlines the number of schools per quintile selected to for the study.

Due to the wealth of diversity within South Africa, and the complexity of coordinating research with multiple provincial departments, schools from only one province, the Western Cape, were included. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be representative of the entire country.

Fieldwork took place during the months of April and May 2020. This directly coincided with the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic when South African schools were closed and challenging to contact. Of the sample of 123 schools, only 87 schools were able to provide their principal's direct contact details. An online questionnaire was sent to these 87 principals, of which 45 attempted the questionnaire and 38 fully completed it, providing a relevant response rate of 44%, or an overall response rate of 31% -considerably higher than in similar studies (Day et al., 2016; Khumalo, Van Vuuren, Van der Westhuizen & Van der Vyver, 2018). Purposive sampling was employed in a sequential manner to conduct semi-structured interviews (Bryman, 2016). Of the 38 respondents who successfully completed the questionnaire, 20 indicated a willingness to be interviewed online, yet only 14 interviews were held.

Overall, the sample was skewed to upper quintile schools. This was to be expected due to their higher socioeconomic status, enabling them to be easier to be contacted via their online presence. Although most schools were in urban areas, a range of types of schools were included in the study, in terms of the number of learners and school fees charged. This aligned with the aim of obtaining a sample reflecting the diversity of schools within the Western Cape. The sample represents one of the largest cohorts of principals in empirical South African research designed to explore perceptions of successful school leadership.

A thematic analysis was deemed the most appropriate qualitative method to identify, analyse and report patterns within the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). I followed Braun and Clarke's (2006) six phases of thematic analysis. Firstly, I became familiar with the data by transcribing the interviews, reading and re-reading the data and noting initial ideas. Secondly, initial codes were generated by systematically coding interesting features of the data. Thirdly, initial themes were searched for by collating codes into potential themes. Fourthly, these initial themes were reviewed by checking whether they resembled the coded extracts and the entire data set. In the fifth place, I defined and named themes through an ongoing analysis of the overall story. Finally, producing the written analysis involved selecting vivid and compelling extracts, constantly relating analysis back to the research question and literature, and creating an academic report of the analysis. This analysis was performed with the help of NVivo research software.

I adhered to the ethical considerations in research set out by both the University of Oxford and the WCED, while also ensuring that the guidelines set by the British Educational Research Association (2018) were followed.

Findings

All individual names mentioned in the analysis are pseudonyms, to ensure the anonymity of participants, and refer to principals who were interviewed. The brackets after each name indicates the principal's school quintile.

In line with a series of extensive reviews (Leithwood, Day, Sammons, Harris & Hopkins, 2006; Leithwood et al., 2004), through a thematic analysis, I identified broad themes of successful school leadership practices, which have been arranged into Maphalala's (2017) three pillars of Ubuntu: intrapersonal values, interpersonal values and contextual values.

Intrapersonal Values

On an intrapersonal level, principals are positive, passionate individuals who love school and have strong morals, values and ethics. Malcolm (Q5) outlined that "if you can get your ego off the table, and you've got high moral values, good integrity, you've got a love for children, and you like the people you work with, then you are well on your way." This highlights the humble nature of principals, which Hestrie (Q5) confirmed by stating that "I am human. So, be human, make mistakes and apologise for making a mistake." Furthermore, successful principals are constantly looking to improve themselves, by being lifelong learners. Charlize (Q5) explained that "it is always a challenge of developing myself, of learning something new."

Successful principals are well-organised individuals although, paradoxically, the school day is filled with both routine and uncertainty. Frans (Q5) explained that "you can almost take last year 's calendar and put it into next year and follow that routine." However, Pat (Q5) mentioned that "it is never the same" as Frans, again, described

it 's never quite what you think it is going to be. Education is a fascinating arena to work in because the curve balls are many and no 2 days are the same, even though much of it is a bureaucratic process. It has a human factor that always makes the unexpected happen.

Successful principals are dedicated and this results in working extremely long hours. Pat (Q5) fittingly expressed that "when school starts, I belong to the school. It is a 24/7 job." Various principals arrive at school at 05:30, while others, such as Pat, mentioned that "maybe four nights a week I am at the school until 23:00." However, these principals love their job and the long hours do not deter them in the slightest, which Malcolm (Q5) epitomised:

So, I make it sound like I work the whole time, but I have a great life. You see, this work I like. It's great work. So, you know, they always say if you find a job [that you like], then you don't actually have to work a day. Working with teenagers is a real reward.

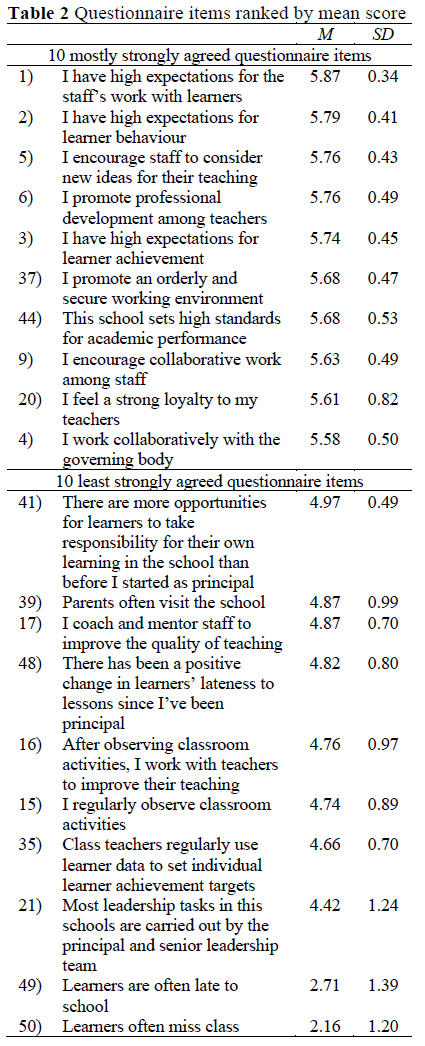

Table 2 illustrates which aspects of school leadership principals valued most and least strongly.

Items related to high expectations, developing people and collaboration had the highest mean values, tending towards strongly agree, while items relating to classroom observations, direct principal impact and the use of data had the lowest mean values, tending towards slightly agree. The standard deviations (SDs) emphasise the consistency in principals' perceptions as the 10 most strongly agreed items had a significantly lower SD (0.49) than the 10 least strongly agreed items (0.94).

It is unsurprising that items relating to learner lateness and attendance had the highest SD, of 1.39, as principals from lower quintile schools are expected to face more challenges of this nature, than their colleagues in upper quintile schools. The reasons for this were outlined in the interviews. For example, Siya (Q1) explained that parents "are working in the farms. They leave very early in the morning and they come back late ... Kids are left alone, so they arrive at school very late, because they are not being monitored." Some of these learners travel from 40 kilometres away, via public transport, which is notoriously problematic, as Charlize (Q5) highlighted: "They leave the moment the bell goes because they need to get home before it gets too dangerous."

Another item, relating to how often parents visited the school, had a large SD, 0.99. Again, there was a considerable difference between the responses of lower and upper quintile school principals. Cheslin (Q3) explained some of the challenges he faced in this regard:

These parents would say no, I can't go to school, there's a problem, I don't have transport ... If Mohammed can't go to the mountains, the mountains must come to Mohammed ... I did home visits to get the parents involved.

Interpersonal Values

In terms of the interpersonal characteristics, successful principals are empathetic, people-orientated individuals who know that, in Hestrie's (Q5) words, "it is important to listen to people." Cheslin (Q3) practically outlined that "you must have an ear to listen to them [staff]. If they come to you with problems, you must have an open door. They must be comfortable in your presence." Various principals mentioned the importance of a supportive family and having good mentors. For example, Malcolm (Q5) stated that "when I started at my first school, there was a group of principals who took me under their wing and without them I think I would have been in big trouble."

Developing people

Ubuntu centres around caring for others. For successful principals this involves growing others and professional development, as Caster (Q3) highlighted: "There must be opportunities for staff to develop themselves." Duane's (Q5) use of observations as an improvement, not a punitive measure underlined this:, "I do class visits to try to help staff ... not to evaluate them."

There is a strong link between developing people and adopting a distributed style of leadership, by trusting others and giving them autonomy. Siya (Q1) succinctly outlined that "leadership needs to be shared." Caster (Q3) emphasised that one must "engage with people and have a collaborative approach to running the school." Developing people centres around the importance of staff, praising others, teamwork and relationships. Hestrie (Q5) aptly concluded that "human relationships are the most important thing."

People centred

Principals were embedded in the fabric of the school by being aware of what was going on at ground level. Siya (Q1) outlined that he was "not an office person. I move around. I chat with the kids. I listen to the kids'" Hestrie (Q5) had "a book with a picture and names of all 736 girls in the school. I study it because I must know all of the girls' names'" While Steve (Q5) went further: "I invite six grade 8s one week, next week six grade 9s, and they have lunch with me in my office and we chat about school. School issues, particularly, to see what is itching, what is working and what is not working. Just to stay in touch with pupils." For schools in challenging areas there is another reason for staying grounded. Cheslin (Q3) outlined that he "must be on patrol" as there are "criminal elements that want to intrude." This is in stark contrast to principals in more affluent schools, who "take a few moments to walk around the school." Additionally, most principals continued to teach as, according to Charlize (Q5), it "is important that the principal is seen as not having lost touch of what goes on in a classroom." Eben (Q5) highlighted that "a principal must be in the curriculum, you can't stay outside and yes, you have to do this, and you have to do that."

Contextual Values

No significant differences were reported in eight of the nine contextual categories. Principals from semi-urban schools (n = 7; M = 4.93) had a significantly lower score than schools from urban (n = 20; M = 5.23) and rural (n = 11; M = 5.27) areas. Considering that principals from urban and rural areas had similar mean scores, caution is urged in claiming that school location significantly affects principals' perceptions of successful school leadership. Additionally, a multi-linear regression was used to explore associations between the overall leadership score and school type, socioeconomic and demographic groups. The regression model was not even remotely close to being statistically significant (F[29,8] = 0.412; p = 0.962). Therefore, it appears that principals from different types of schools, socioeconomic and demographic groups do not significantly differ in their overall perceptions of successful school leadership.

However, interviews revealed that context permeates every aspect of school leadership. For example, Siya (Q1) outlined that "our parents haven't gone to school, they cannot assist their kids with homework, so we need to organise extra classes after school." This affects school structure, community involvement, how staff are developed and the school culture, among other elements. Cheslin's (Q3) experience added further insight:

To deal with these learners every day is very hard. Some of these learners come from another type of culture, using another type of language. So, now, we must learn to adapt to these learners. Number one, they are poor. Number two, most are coming from the Eastern Cape, they are staying all by themselves. There are no adults who are responsible for them. They are responsible for themselves.

The questionnaire analysis revealed that principals from upper quintile schools expressed a greater trust in their staff. More privileged schools can often "recruit people who want to contribute", as Charlize (Q5) mentioned. In contrast, lower quintile schools, as Siya's (Q1) experience illustrates, "are only taking the leftovers. And they do not even stay here over the weekends, on Fridays they want to go back to Cape Town." Similarly, there was difference between lower and upper quintile school principals' perceptions about learner safety at school. This highlights the inseparable nature of schools and the communities they serve, as Caster (Q3) explained:

We have been burgled quite a lot. The social problems of the community are spilling onto the school. There are quite a number of cases where our kids abuse drugs. Community problems become part of the fabric of the school as well ... They live in a very violent society.

Redesigning the organisation

School context also involves building structure, developing the curriculum and aligning the school with teaching and learning. Caster (Q3) explained that this involved "making sure that you assist in getting the conditions perfect for quality learning and teaching to happen." Often, this requires change, as Pieter (Q5) explained: "We had to reorganise. Mainly, some structural changes." Hestrie (Q5) outlined her approach: "I did not change anything immediately. I said I would wait 2 years first." Willie (Q5) used a different strategy: "there was so much wrong, that I just decided, you can't go and try and change a ship, and then just keep on sailing knowing that you are going the wrong way. So, you had to change." The different approaches highlight that although there are similar themes and trends, principals differ in their practical applications, depending on their context.

Setting direction

Redesigning the organisation rests on the school's vision. Willie (Q5) asserted that "you have to get everybody on board. And have them move in the same direction." This is crucial, as Pieter (Q5) stated: "so everybody knows where they are going." Essentially, it encompasses, in Pat's (Q5) words, getting "the ship from A to B." John (Q5) demonstrated how the vision is concerned with "equipping [learners] with the life skills to go out into the world, do positive things, excel, and be an asset to their families, to their communities."

Similarly, Caster (Q3) illustrated the interconnected nature of the vision, values and holistic approach: "What was important is that learners become good citizens." Steve (Q5) highlighted that "I want parents to know what we are doing. So, they can think okay, good, the school is moving forward."

Setting direction, as Pat (Q5) testified, requires principals "to be futuristic, to plot the course." Siya (Q1) declared that this obliges principals to "walk the talk." Fittingly, Caster (Q3) clarified that "there are a lot of responsibilities that you have, but the role is to lead by example." Malcolm (Q5) explained how this is derived through servant leadership: "Don't expect anyone to do something which you are not prepared to do yourself. "

Leadership style

Although most principals openly spoke about a democratic and distributed style of leadership, their approach changed and adapted to the context and environment. For example, Cheslin (Q3) stated that "when you are in leadership position, you must use all types of leadership that is available at a specific time. Sometimes you must be an educationalist, sometimes you must be a dictator, sometimes you must be democratic." Additionally, a problem-solving mentality, with a willingness to improve things, is an important factor, as Malcolm (Q5) explained: "We have control over everything, and if you don't like how things are happening, then let's make a change."

These findings suggest that while perceptions of successful school leadership are consistent among principals from different types of schools, socioeconomic and demographic groups, how they are implemented depends on the context of the school. Frans (Q5) succinctly portrayed this paradox: "Each context is unique ... You've got an environment around you that also shapes the way you interact and behave, and sometimes some of your self-held beliefs have to change completely, depending on the environment you find yourself in. "

Ubuntu at the Heart of School Leadership Successful principals are aware of the unequal nature of South African society and education's role in building a brighter future for the country. This perspective, coupled with an unwavering desire to make a difference in the lives of others, was expressed in all interviews. For example, Pat (Q5) stated that "I just felt I could make a difference here, make a difference to the kids' lives, to the community." Cheslin (Q3) further expressed that "for me it was not to change them, but be a part of changing them. That was my motivation. To make a difference."

Principals in affluent schools were conscious of their privilege. Frans (Q5) outlined that "there are very different lives out there in this country and I am constantly aware how lucky I am to be in the sort of first world environment, when so many people are never in that." The high levels of inequality bring severe differences in the types of challenges principals face. Siya (Q1) explained that "the intelligence came to me to tell me that Mr Siya, you are going to die . There are seven educators who are planning with other learners here at school, that you will be assassinated." While in upper quintile schools the challenges often concern the demographics of the school, as John (Q5) conceded: "it is a fact our learner body does not reflect the demographics of the country, but it does reflect the demographics where we live, where we are situated." Frans (Q5) explained that "we are using that [privilege] to change lives, to create leaders and we are giving a slice of that pie to kids who would not have had it in any other circumstance."

Discussion

Intrapersonal Values

Successful high school principals are passionate, resilient individuals with strong moral and ethical values, confirming Prozesky's (2016:6) claim that "ethical quality is seen as paramount." Successful principals are ambitious, positive and humble people who are always looking to improve themselves by being lifelong learners, which reinforces Leithwood, Harris and Hopkins' (2008:36) view that "the most successful school leaders are open-minded and ready to learn from others." This, coupled with their hardworking temperament, resonates with the idea that successful principals go "the extra mile" (Chikoko et al., 2015:459). They set the example by working extremely hard, although this does not discourage them, as they love what they do. However, this does raise concerns about well-being and work-life balance.

The contradictory combination of uncertainty and routine means that successful principals are simultaneously strategic and well-organised individuals, yet equally flexible to adapt to the inevitable changes, or unexpected events that typically arise in a school environment. This uncertainty does not deter successful principals, rather, as Boyatzis and McKee (2005:3) state, "great leaders face the uncertainty of today' s world with hope." This hope comes in the form of the school's vision, allowing others to see how their role fits in the bigger picture, and their personal optimism. Additionally, this flexibility reinforces the assertion that the most skilful leaders "are those who bend restrictive external forces to serve the best interests of the school" (Taylor et al., 2019:34).

They tend to have a problem-solving mentality and relish challenges, which supports Hargreaves and Harris' (2015:38) finding that "for leaders who perform beyond expectations, crises are catalysts for change. " Most importantly, their social conscience ensures that they strive to make a positive difference in the lives of others and understand their role in terms of the big picture, the potential of education to create a better South Africa, by being well aware of the vast inequalities throughout the country. This reveals that successful principals' intrapersonal values are consistent with established literature, particularly Gurr's (2015) model and Msila's (2014) application of leading schools through Ubuntu.

Interpersonal Values

Successful principals are people orientated, empathetic and value highly the importance of listening to others (Grobler, Moloi & Thakhordas, 2017). They create an open environment where others can grow and develop. They invest in people and trust others to do their job with freedom and autonomy. Principals are also embedded in the fabric of the school by being on the ground, knowing staff and learners, and are visible to the community. Continuing to teach classes aided in this regard. This echoes Naicker's (2015) findings which explain the influence of Ubuntu in South African school leadership through developing people as well as being empathetic and open to staff.

Few of the above intrapersonal and interpersonal traits are unique to this study as considerable research has outlined the constituents of successful principals (Day, 2015; Day et al., 2016; Hargreaves, 2004; Mawdsley et al., 2014). However, it is useful to see how this plays out in a South African context and influence professional characteristics and practices.

Contextual Values

Importantly, I found that principals from different types of schools, socioeconomic and demographic groups did not significantly differ in their overall perceptions of successful school leadership. While the perceptions of successful school leadership appear to be similar for high-achieving high school principals in the Western Cape, implementation depends on the individual and school context, as the environment heavily shapes the nature and application of school leadership. The considerable discrepancies in experiences between principals from lower and upper quintile schools demonstrate the array of challenges in a vastly unequal society -a situation to which many other developing countries can attest.

The data confirmed research that objects to the narrowing of school leadership to dichotomising styles (Day et al., 2016; Leithwood & Sun, 2012). Successful principals amalgamate transformational, instructional and distributed leadership styles in their everyday practice, although the emphasis of each style changes to suit the context. These findings resonate with Day et al.'s (2016:244) concept of "the layering of leadership", and Hargreaves and Harris' (2015:43) notion of "fusion leadership", demonstrating that there is no single successful leadership strategy, style or formula for success. Rather, successful principals integrate styles and use whichever strategy they believe is necessary based on the current situation, context, staff capabilities, community expectations, school culture and their personal and professional strengths. While other studies (Day et al., 2016; Printy et al., 2009) have focused on transformational and instructional leadership, the value of my study lies in the prominence of distributed leadership, after heeding the advice of earlier research in South African school leadership (Bush & Glover, 2016; Ngcobo & Tikly, 2010).

Conclusion

Schools are complex. Being a principal is complex. Being a successful principal is so much more than just being a principal. It is about setting the direction, developing people, redesigning the organisation, adapting one's leadership style to suit the situation, being embedded in the fabric of the school, being equally organised, yet flexible, dedicated, passionate, empathetic, hardworking, people-orientated, but most importantly, wanting to make a positive difference in the lives of others. It is about living with Ubuntu.

These results reveal the interdependence of intrapersonal, interpersonal and contextual values of successful high school principals in the Western Cape. Successful school leadership is equally concerned with what you do, who you are and where you are.

Ultimately, the primary contribution of my study lies in building on Maphalala's (2017) pillars of Ubuntu and confirming the findings of established international literature, particularly Day et al. (2016), Hargreaves and Harris (2015) and Leithwood et al. (2004) but presenting these in a South African context. In this light, my study points towards both the uniqueness and universality of successful school leadership in South Africa. Universalities identified in this study have been found in other school leadership research, but there is a distinct manner in how these aspects come together in the South African context under the three pillars of Ubuntu.

In conclusion, successful school leadership cannot be categorised into a single style, outlined by certain adjectives, or defined by a list of simplistic practices. There is no silver bullet, or best approach. Rather, successful school leadership is flexible, adaptive, evolves to suit the context and is based on Ubuntu. Successful principals fundamentally understand the social, cultural, economic and political environment around them, the capabilities of their staff, the demands of their community, their public responsibility and their own professional and personal strengths and weaknesses. Successful principals incorporate these aspects with an amalgamation of leadership styles, the core practices of setting direction, developing people and redesigning the organisation, and a desire to make a difference in the lives of others.

Future research would benefit from incorporating a larger sample and including more, if not all, of the country's provinces to determine whether the findings from this study are consistent for the entire country. Longitudinal studies would be better suited to track the relationship between principal practices and learner achievement over time in a South African context, as this has yet to be done. Continuing to investigate personal characteristics and practices, along with professional characteristics, should be a hallmark of future research as my study's results suggest their inseparability. In this light, further investigation of "contextual intelligence" (Clarke & O'Donoghue, 2017:179), borrowed from Kutz (2008), is needed to explore exactly how principals adapt their practices due to context.

Notes

i. This article is based on the master's thesis of Michael Kramer.

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Boyatzis RE & McKee A 2005. Resonant leadership: Renewing yourself and connecting with others through mindfulness, hope, and compassion. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

British Educational Research Association 2018. Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed). London, England: Author. Available at https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Bryman A 2016. Social research methods (5th ed). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bush T & Glover 2016. School leadership and management in South Africa: Findings from a systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(2):211-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2014-0101 [ Links ]

Bush T, Kiggundu E & Moorosi P 2011. Preparing new principals in South Africa: The ACE: School Leadership programme. South African Journal of Education, 31(1):31-43. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n1a356 [ Links ]

Castillo FA & Hallinger P 2018. Systematic review of research on educational leadership and management in Latin America, 1991 -2017. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(2):207-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217745882 [ Links ]

Chikoko V, Naicker I & Mthiyane S 2015. School leadership practices that work in areas of multiple deprivation in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(3):452-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143215570186 [ Links ]

Clarke S & O'Donoghue T 2017. Educational leadership and context: A rendering of an inseparable relationship. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(2):167-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1199772 [ Links ]

Cramm JM, Nieboer AP, Finkenflügel H & Lorenzo T 2013. Disabled youth in South Africa: Barriers to education. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 12(1):31 -35. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijdhd-2012-0122 [ Links ]

Creswell JW & Plano Clark VL 2017. Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Day C 2015. International Successful School Principals Project (ISSPP): Multi-perspective research on school principals. Nottingham, England: The University of Nottingham. Available at https://www.uv.uio.no/ils/english/research/projects/isspp/brochure/isspp-brochure-27_jul_final_amended.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Day C, Gu Q & Sammons P 2016. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Education Administration Quarterly, 52(2):221-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X15616863 [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2008. Understand school leadership and governance in the South African context. Tshwane, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.oerafrica.org/system/files/8867/understandschoolleadershipandgovernanceinthesouthafricancontext_ 0.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=8867&force=1. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Dimmock C & Walker A 2000. Globalisation and societal culture: Redefining schooling and school leadership in the twenty-first century. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 30(3):303-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/713657474 [ Links ]

Fetters MD & Freshwater D 2015. The 1 + 1 = 3 integration challenge. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(2):115-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815581222 [ Links ]

Gilmour D & Soudien C 2009. Learning and equitable access in the Western Cape, South Africa. Comparative Education, 45(2):281-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902920989 [ Links ]

Grobler B, Moloi C & Thakhordas S 2017. Teachers' perceptions of the utilisation of Emotional Intelligence by their school principals to manage mandated curriculum change processes. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45(2):336-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143215608197 [ Links ]

Gurr D 2015. A model of successful school leadership from the International Successful School Principalship Project [Special issue]. Societies, 5(1):136-150. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5010136 [ Links ]

Hallinger P 2003. Leading Educational Change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3):329-352. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764032000122005 [ Links ]

Hallinger P 2019. A systematic review of research on educational leadership and management in South Africa: Mapping knowledge production in a developing society. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 22(3):316-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1463460 [ Links ]

Hargreaves A 2004. Inclusive and exclusive educational change: Emotional responses of teachers and implications for leadership. School Leadership & Management, 24(3):287-309. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243042000266936 [ Links ]

Hargreaves A & Harris A 2015. High performance leadership in unusually challenging educational circumstances. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri, 3(1):28-49. https://doi.org/10.12697/eha.2015.3.1.02b [ Links ]

Harris A, Chapman C, Muijs D, Russ J & Stoll L 2006. Improving schools in challenging contexts: Exploring the possible. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(4):409-424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600743483 [ Links ]

Jansen L 2016. 'Lack of leadership, quality at schools'. Cape Times, 19 January. Available at https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/lack-of-leadership-quality-at-schools-1972626. Accessed 17 July 2020. [ Links ]

Khumalo JB, Van Vuuren HJ, Van der Westhuizen PC & Van der Vyver CP 2018. Problems experienced by secondary school deputy principals in diverse contexts: A South African study. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 16(2):190-199. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.16(2).2018.17 [ Links ]

Kutz MR 2008. Toward a conceptual model of contextual intelligence: A transferable leadership construct. Leadership Review, 8:18-31. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Matt-Kutz/publication/228464894_Toward_a_conceptual_model_of_contextual_intelligence_A_transferabl e_leadership_construct/links/5421587f0cf203f155c 65ae2/Toward-a-conceptual-model-of-contextual-intelligence-A-transferable-leadership-construct.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Leibbrandt M, Finn A & Woolard I 2012. Describing and decomposing post-apartheid income inequality in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 29(1):19-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.645639 [ Links ]

Leithwood K, Day C, Sammons P, Harris A & Hopkins D 2006. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. Nottingham, England: Department for Education and Skills. [ Links ]

Leithwood K, Harris A & Hopkins D 2008. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1):27-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060 [ Links ]

Leithwood K & Jantzi D 2005. A review of transformational school leadership research 1996-2005. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3):177-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500244769 [ Links ]

Leithwood K, Seashore Louis K, Anderson S & Wahlstrom K 2004. Review of research: How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. Available at https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/documents/how-leadership-influences-student-learning.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Leithwood K & Sun J 2012. The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3):387-423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11436268 [ Links ]

Maphalala MC 2017. Embracing Ubuntu in managing effective classrooms. Gender and Behaviour, 15(4):10237-10249. [ Links ]

Marks HM & Printy SM 2003. Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Education Administration Quarterly, 39(3):370-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X03253412 [ Links ]

Mawdsley RD, Bipath K & Mawdsley JL 2014. Functional urban schools amid dysfunctional settings: Lessons from South Africa. Education and Urban Society, 46(3):377-394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124512449859 [ Links ]

Mbigi L 2000. In search of the African business renaissance: An African cultural perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Knowledge Resources. [ Links ]

Mertkan S, Arsan N, Cavlan GI & Aliusta GO 2017. Diversity and equality in academic publishing: The case of educational leadership. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(1):46-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2015.1136924 [ Links ]

Morse JM 2010. Procedures and practice of mixed method design: Maintaining control, rigor, and complexity. In A Tashakkori & C Teddlie (eds). Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335193.n14 [ Links ]

Motala S, Dieltiens V & Sayed Y 2009. Physical access to schooling in South Africa: Mapping dropout, repetition and age-grade progression in two districts. Comparative Education, 45(2):251-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902920948 [ Links ]

Msila V 2008. Ubuntu and school leadership. Journal of Education, 44(1):67-84. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vuyisile-Msila/publication/228625626_Ubuntu_and_school_leadership/links/0912f50c829b19ec3a000000/Ubuntu-and-school-leadership.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Msila V 2010. Rural school principals' quest for effectiveness: Lessons from the field. Journal of Education, 48(1):169-189. [ Links ]

Msila V 2014. African leadership models in education: Leading institutions through Ubuntu. The Anthropologist, 18(3): 1105-1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891593 [ Links ]

Muijs D, Harris A, Chapman C, Stoll L & Russ J 2004. Improving schools in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas - A review of research evidence. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 15(2):149-175. https://doi.org/10.1076/sesi.15.2.149.30433 [ Links ]

Mulford B 2008. The leadership challenge: Improving learning in schools (Australian Education Review, 53). Camberwell, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) Press. Available at https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=aer. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Naicker I 2015. School principals enacting the values of Ubuntu in school leadership: The voices of teachers. Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 13(1):1 -9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972639X.2015.11886706 [ Links ]

Nettles SM & Herrington C 2007. Revisiting the importance of the direct effects of school leadership on student achievement: The implications for school improvement policy. Peabody Journal of Education, 82(4):724-736. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560701603239 [ Links ]

Ngcobo T & Tikly LP 2010. Key dimensions of effective leadership for change: A focus on township and rural schools in South Africa. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 38(2):202-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143209356359 [ Links ]

O'Donnell RJ & White GP 2005. Within the accountability era: Principals' instructional leadership behaviors and student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 89(645):56-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263650508964505 [ Links ]

Pearce LD 2015. Thinking outside the Q boxes: Further motivating a mixed research perspective. In S Hesse-Biber & RB Johnson (eds). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Printy SM, Marks HM & Bowers AJ 2009. Integrated leadership: How principals and teachers share transformational and instructional influence. Journal of School Leadership, 19(5):504-532. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460901900501 [ Links ]

Prozesky M 2016. Ethical leadership resources in southern Africa's Sesotho-speaking culture and in King Moshoeshoe I. Journal of Global Ethics, 12(1):6-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2016.1146789 [ Links ]

Robinson V, Hohepa M & Lloyd C 2009. School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland. [ Links ]

Roodt M 2018. The South African education crisis: Giving power back to parents. Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Institute of Race Relations. Available at https://irr.org.za/reports/occasional-reports/files/the-south-african-education-crisis-31-05-2018.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Spaull N 2019. Increase in 2018 Matric bachelor's passes means universities headed for a perfect storm. Daily Maverick, 7 January. Available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-01-07-increase-in-2018-matric-bachelors-passes-means-universities-headed-for-a-perfect-storm/. Accessed 24 December 2019. [ Links ]

Spillane JP 2006. Distributed leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Sweetland SR & Hoy WK 2000. School characteristics and educational outcomes: Toward an organizational model of student achievement in middle schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(5):703-729. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131610021969173 [ Links ]

Taylor N, Wills G & Hoadley U 2019. Addressing the 'leadership conundrum' through a mixed methods study of school leadership for literacy. Research in Comparative and International Education, 14(1):30-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499919828928 [ Links ]

Western Cape Education Department 2005. WCED task team to drive numeracy and literacy strategies, media release, 24 May. Available at https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/comms/press/2005/29_numlit.html. Accessed 24 December 2019. [ Links ]

Wills G 2017. What do you mean by 'good'? The search for exceptional primary schools in South Africa's no-fee school system (Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: WP16/2017). Stellenbosch, South Africa: Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch. Available at https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/wp162017.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

World Bank 2020. Gini index - South Africa. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI7locations=ZA. Accessed 26 July 2020. [ Links ]

Zoch A 2017. The effect of neighbourhoods and school quality on education and labour market outcomes in South Africa (Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: WP08/2017). Stellenbosch, South Africa: Department of Economics and the Bureau for Economic Research, University of Stellenbosch. Available at https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/wp082017.pdf. Accessed 6 October 2023. [ Links ]

Received: 16 January 2021

Revised: 2 March 2023

Accepted: 27 June 2023

Published: 31 August 2023