Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n3al637

ARTICLES

"We need our own super heroes and their stories" - Towards decolonised teaching within the management sciences

Willie Chinyamurindi

Department of Business Management, Faculty of Management and Commerce, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa. wchinyamurindi@ufh.ac.za

ABSTRACT

There are growing calls for a decolonised curriculum. With the study reported on here, I offered an understanding of this critical topic through student voices. In this study, I illustrated how super heroes and their stories could contribute to decolonised teaching informed by the findings of the research. I specifically used the views of 30 final-year students enrolled in a strategic management course at a rural university in South Africa. Data were collected using a focus-group technique relying on group interviews. Students were asked to evaluate their experiences during the semester-long course, focusing on their understanding of aspects that could be improved given the decolonial tide. Two narratives emerged from the analysis as crucial findings. Firstly, the students expressed a desire for super heroes in the form of individuals that they can relate to to feature in higher education teaching. Secondly, related to the first request, the students also needed stories relatable to their context as a dominant feature in such teaching. I interrogate the role of the 2 findings in informing a decolonised curriculum and improving my teaching practice.

Keywords: decolonised teaching; higher education; social constructivism; South Africa; super hero stories

Introduction and Background

There are growing calls for the need to decolonise teaching within the higher education sector (Chinyamurindi, 2023). Such calls have gained notoriety internationally (Aman, 2018) and in South Africa (Hlatshwayo, Adendorff, Blackie, Fataar & Maluleka, 2022). The need for a decolonised curriculum is described as one of "the most difficult questions facing educators at universities in South Africa today" (Olivier, 2018:2). This places importance on research that extends our understanding of decolonisation (Heleta, 2016). In answering such calls, the modern university can play an essential role in reversing what could be perceived as challenges that have a colonial legacy (Dawson, 2020). These challenges manifest currently in teaching and learning in present-day universities (Gleason & Franklin-Phipps, 2019). Such a situation places importance on the work of change that must be done with "caution" and consistency through decolonisation (Hungwe & Ndofirepi, 2021:54). This type of change through curriculum reform seeks to level the playing field (Moncrieffe, Race & Harris, 2020). This places importance on the decolonial agenda (Mbembe, 2016), especially within higher education (Chinyamurindi, 2023). At the core of this decolonisation work is knowledge production (Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Smit, 2017). Such an issue could be an activity that the African university may need to engage in through efforts and activities that inculcate decolonisation (Waghid, 2021). As argued by Canham (2018:319), this calls for a "praxis towards decolonial action."

Knowledge is deemed a crucial part of any society. There is a need to acknowledge multiple ways of knowing (Smith, 2016). The colonial project may have challenged this idea of multiple ways of knowing. Here, colonisation was presented as a dominant logic (Martin, Stewart, Watson, Silva, Teisina, Matapo & Mika, 2020). The result could be to place specific contexts and their knowledge systems on a higher pedestal. Such a situation attests to knowledge as a domain of power (Bourdieu, 1982; Foucault, 1970; Herman & Chomsky, 1988). Other scholars bemoan that modern universities promote this dominant logic of knowledge (Mbembe, 2015). This has resulted in minority groups, including indigenous knowledge systems, lagging and often perceived as being inferior knowledge systems (Giancarlo, 2020). Within a higher education system, this robs students of the potential to learn about others (Arday, Belluigi & Thomas, 2021). Countries like South Africa may do well to also learn from other countries where the voices of minority groups and their knowledge systems are being elevated in the current era (Manathunga, 2020; Manathunga, Qi, Raciti, Gilbey, Stanton & Singh, 2022).

Statement of the Problem

Calls exist for research and practice-based interventions that promote the decolonisation of knowledge. Such a focus promotes processual actions that seek to make knowledge creation equal (Cummings, Regeer, De Haan, Zweekhorst & Bunders, 2018). This decolonisation of knowledge is argued to be with its complexity and ensuing tensions (De Oliveira Andreotti, Stein, Ahenakew & Hunt, 2015). Such complexity and ensuing tensions originate in how knowledge has traditionally been viewed and created, favouring dominant race groups (Crilly, Panesar & Suka-Bill, 2020). Furthermore, there are calls within the Global South to push and advance their knowledge bases, which should be addressed (Brandner & Cummings, 2017; Manathunga, 2020).

For the past 10 years I have been working at a university classified as a historically disadvantaged institution (HDI). I teach a module, "strategic management", offered at third-year level to exit students. In keeping with international standards, the aim with the module is to introduce students to the theoretical aspects concerning strategic management in organisations. Students are also allowed to explore debates and developments including concepts and techniques within strategic management (Okumus & Wong, 2005). Furthermore, students are allowed to apply this theory in trying to solve real-world case examples faced by contemporary organisations. This also aligns with international standards in teaching strategic management (Coetzer & Sitlington, 2014).

Some observations can be noted regarding existing research around the teaching of strategic management. Firstly, the dominant theories used within strategic management mostly originate from Western scholars' influences, mostly from the United States of America (Napshin & Marchisio, 2017). Secondly, most of the tools and techniques we use in teaching students also have their origin from Western scholars as key contributors (Bell & Rochford, 2016). Thirdly, there is encouragement for more Global South interventions in case-based analysis, especially in the international arena (De Paula Arruda Filho & Przybylowicz Beuter, 2020). The South African issues for a decolonised curriculum motivated this study in addition to the observations around teaching strategic management.

Literature Review

The call for relatedness of a student's situation in teaching becomes a crucial aspect of a decolonised curriculum. Such a call could frame the importance of paying attention to conditions that influence teaching and learning. These conditions could include factors and agents inside and outside the university (Msila, 2023). Furthermore, the relatedness could extend to decolonised teaching that also informs research (Kessi & Boonzaier, 2018). Barnes (2018) links this necessity for decolonisation to the methods used to generate knowledge.

On one end are essential factors related to the interaction between the lecturer and student. Matthews (2021) gives an example of this by alerting lecturers to be mindful of issues related to how the student identity develops as part of learning. This is supported by Kiguwa and Segalo (2018) who opine that there is a need for lecturers to be mindful of the contexts from which students come. These issues subsequently influence and intersect with aspects related to knowledge creation. For lecturers, this gives cadence to an ongoing work of understanding their students' background and current needs because of efforts to promote a decolonised curriculum (Agherdien, Pillay, Dube & Masinga, 2022).

An aspect of identity work crucial in promoting decolonisation entails consideration for the language of instruction (Hassan, 2022). This quest could be framed within the wider affordance in the higher education sector for using and seeing value in the role of history, culture, language and identity in informing learning outcomes (De Beer & Kriek, 2021). The desire here is to debunk the notion that African cultural belief systems are inferior in favour of Western scientific thinking (Ally & August, 2018). At the core here could be power issues with knowledge as the contestation (Leibowitz, 2017).

Conversely, another set of factors concerns the content of what is being taught or that which is "happening in lecture halls" as important (Laakso & Hallberg Adu, 2023:1). Such efforts of what is being taught in the classroom should also be supported through wider university interventions. This could entail a process of self-introspection for lecturers on the content being taught to students and whether it enforces colonial biases (Aby, 2022). Such introspection considers the role of both the "hidden" and the "null" regarding curriculum (Kiguwa & Segalo, 2018:310). In response, others position the need for broader interventions at the institutional level in the form of strategies that encourage a decolonised teaching curriculum (Madhav & Baron, 2022). Such institutional capabilities should be aligned with quests to promote a transformed higher education agenda that encourages quests to promote decolonisation (Msila, 2017). The work of decolonisation should not only be seeking to replace what is deemed colonial knowledge but also finding ways of giving voice to those who may have been "marginalised" and "decentered" (Arshad, 2021:para. 4). This decolonial work may also need to fuse the theoretical with the practical in assisting the student and enhancing the learning experience (Godsell, 2021). Alternatively, this is a fusion of practice and knowledge as crucial efforts toward decolonisation (Ratele, Cornell, Dlamini, Helman, Malherbe & Titi, 2018).

Research Question

Based on the literature, the following research question was set: What does decolonisation mean to a sample of final-year students, and how do the students view decolonisation of the curriculum happening as part of their experience as students?

Methodology

To answer the proposed research question, the socio-cultural theory (SCT) (Vygotsky, 1978) was used as a lens for the study. Through the SCT, I was able to understand how my students not only experienced teaching and learning interventions but also how it was shaped by the environment (Bandura, 1986). In the SCT, I was also able to frame understanding of how students model learning experiences informed by their experiences.

Importantly, through the SCT, I was able to hear from students which aspects were deemed desirable and undesirable based on the teaching and learning interventions.

In my view, the SCT assisted greatly with the methodology adopted in which stories and narratives were used. At the core of these stories and narratives (as espoused by the SCT) are agentic voices (Bandura, 1986). Importantly, this involves understanding how three elements influence individual behaviour (Pajares, Prestin, Chen & Nabi, 2009), namely a) the student having individual agency; b) the role of significant others having proxy agency to the student and c) the role of the context and its factors having a collective agency of influence. From all this interaction, some form of meaning-making emerges that leads to the development of ideas (Campano, 2007; Smagorinsky, 2011).

Thus, the SCT can be used to understand how students' potential use of information influences their actions and aspirations (Chang, 2013). This can assist in framing student understanding and sense-making (Chambers & Buzinde, 2015). At best, the aim here is to re-write the narrative using schemas within the socio-cultural milieu to write a present-day narrative. Through the SCT we can understand how students understand and make sense of their teaching and learning context to include what is taught and how this teaching happens.

I adopted the interpretivist philosophy and the exploratory research design. A qualitative approach was used, informed by the philosophy and the research design. All this allowed me to explore issues deemed complex, only sometimes done through a quantitative research approach. This was a benefit of using the qualitative research approach. In using the participants' stories and narratives I was able to reflect deeply on the issues under study (Lyons, Bike, Johnson & Bethea, 2012). A focus-group technique was used as a means of collecting data through interviews being done with the participants within a group setting.

Sampling

Three groups of 10 students each were formed (n = 30). The students were informed of the research and its intended benefits at the start of the semester. Those students who wanted to take part would then sign up with me, their lecturer. Upon agreeing to participate in the research, participants completed a form regarding their demographic characteristics. After completion of the form, 16 males (53%) and 14 females (47%) of which 90% were Black and 10% Coloured took part in the study. The majority of respondents were between 20 and 25 years old (57.7%), 37.8% were between 26 and 30 years old while 4.5% were between 31 and 35 years. All the students were in their final year of study and had been registered for a minimum of 3 years in the commerce discipline.

Data Collection

For a month, all the participating students in their respective groups met once a week for data collection. The focus groups were all conducted in English. A dedicated lecture hall was used allowing for spaces where groups could meet. With the participants' permission, all interviews were recorded to allow for ease in transcribing the interview data. All interview questions were in English.

Data Analysis

The data analysis procedure was guided by suggestions from previous narrative research (McCormack, 2000:282). Firstly, the completed transcriptions were imported into QSR NVivo Version 11 software. Secondly, a data analysis procedure based on three levels of meaning-making was adopted (Thornhill, Clare & May, 2004:188).

Level 1 was performed by re-reading each interview and listening to the audio recordings. This process helped me to understand and identify markers from each story to answer the research question. In level 2, participants' responses were classified into meaningful categories. Quotes based on perceptions around decolonisation were then used to illustrate the markers. Level 3 helped me to analyse the content of the gathered narrative accounts and themes. This way of analysis allowed cross-case comparison in understanding participants' sense-making around their lived experiences (Nachmias & Nachmias, 1996).

Ethical Consideration and Trustworthiness The necessary ethical clearance was obtained from the university where the study was conducted. Participation in the study was voluntarily and signed informed consent was a prerequisite for participation. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed as students were informed of their rights and that participating in the study was voluntary.

To ensure data quality, some steps were guided by other scholars' advice (e.g., Guba & Lincoln, 1981). Firstly, initial interview questions were pre-tested with a sample of 10 students (non-participants) who fit the same profile as those interviewed in the main part of the research. Secondly, all interview data were recorded and transcribed verbatim within 24 hours to ensure credible data. Thirdly, after transcription, participants were emailed a copy of the transcription to verify whether the transcription of the interview was accurate. Finally, in addition to the recordings, comprehensive notes were taken at all critical stages of the research for additional depth and quality.

Results

From the data collected, two major narratives emerged. Firstly, the students expressed a desire for "super heroes" in the form of individuals who they could relate to to feature as part of their experience of the teaching of the strategic management course. Secondly, and related to the first request, the students also needed stories relatable to their context as a dominant feature to characterise their learning experience. I interrogate the role of the two findings in informing a decolonised curriculum and improving my teaching practice.

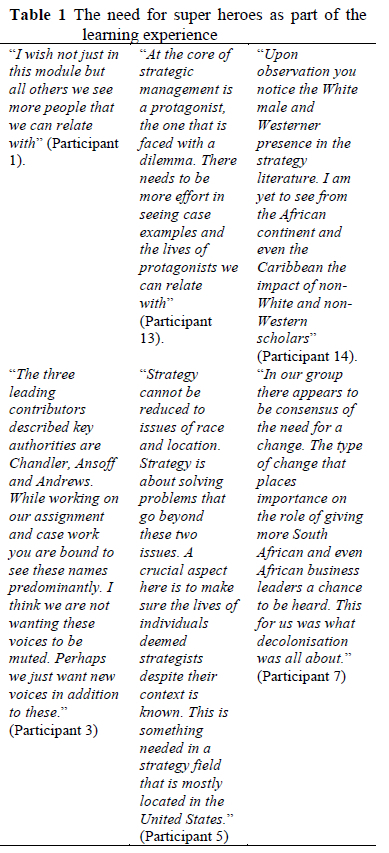

The Need for Super Heroes as Part of the Learning Experience

The participants' first narrative was mainly about the desire to see more relatable individuals as part of the learning experience. Students praised the already existing super heroes within strategic management teaching. However, the students noted the absence of those super heroes specific to their context. For instance, one participant expressed this:

Most of strategic management teaching relies on the contribution of people like Michael Porter and Henry Mintzberg. You can just see from the name that these are all Westerners. I appreciate the contribution such names have made. However, aspiring to be a strategist, I want to see more different names. These should be names like the people I see in my day-to-day interaction. (Participant 6)

Another student noted the name of South African business strategists, especially in the mainstream literature. Blame was put on how the textbook appears not to find the story of African strategists appealing. The student gave an example of the recent case they dealt with concerning Richard Branson.

I appreciate the brains in people like Richard Branson, a British entrepreneur with control in some international companies. In reading about Richard Branson, I was filled with praise for his work to build his empire and the decision processes around this. A concern from my side is that experience of Branson may not resonate with me. Also I am sure we have our own South African strategists and entrepreneurs we do not hear about. (Participant 2)

Trying to understand what the students needed to see regarding these new super heroes, one student flagged the need for representation, especially by race and gender:

I think we need to see more people like us in the cases we are taught. This could mean in terms of colour - most students at this university are Black. We also need to see more women featuring, especially in leadership and general management teaching. (Participant 21)

Based on the first finding and the illustrating quotes, the framing of decolonisation of the curriculum appeals here to a level of relatedness, especially considering the individuals that feature in strategic management teaching. Table 1 illustrates additional quotes to support those regarding the first narrative.

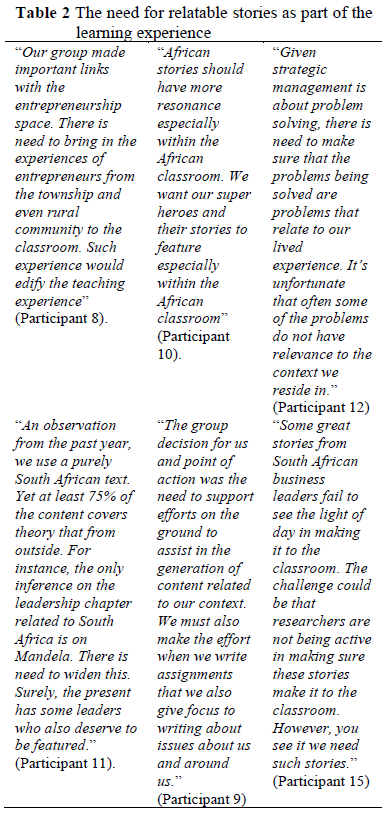

The Need for Relatable Stories as Part of the Learning Experience

The second narrative from the finding related to the first was a request for stories that students could relate to. A core aspect of the teaching and learning within the strategic management course is training students in the skill of problem-solving. The use of cases becomes vital in developing this skill. Participants in the study reflected on this.

One participant noted the absence of a poverty factor in the Western stories and cases used in strategic management teaching.

If you could observe the path to greatness often portrayed in the stories we read about. You notice a huge difference in our experiences. For instance, the rise of African strategists is often one different. The social class issues and structural challenge differ predominantly between countries. I really would relate more and understand an issue relatable to my context. (Participant 4)

Another student gave the example of a famous case used in teaching about fraud in the business of Enron.

When it came to the section on discussing ethics in business, the Enron case was such an eye-opener. The depth of corruption in that case made for helpful information and encouraged us as future business leaders to be mindful. However, here in South Africa, we have our own Enron case, State Capture. Unfortunately, the case has not yet made it to the textbooks. In addition to Enron, we also need to bring in relatable ethical dilemmas to business students. (Participant 19)

Finally, the students were also calling for positive stories from their own contexts to be transmitted to the classroom. One participant expressed this as follows:

There is a romanticism that comes with the West. Sadly, there is also a demonisation of anything African. I am sure there are great case examples from South Africa and the African continent struggling to make the day in our classroom. Take, for instance, on the African continent, the successes of Ethiopian Airways and how such case examples struggle to make it to the classroom. We also need to see good news stories from our context. (Participant 30)

Table 2 illustrates additional quotes to support those regarding the first narrative.

Discussion

With this study I sought to illustrate students' views regarding aspects of their teaching experience that could be decolonised. In doing so, two illustrative findings are used. Firstly, the role of new super heroes is framed as a crucial aspect of decolonisation work to be done. Here students are called to use characters and personalities familiar to them and within their context. Secondly, the students clarified the need for stories relatable to their context. These two narratives can be regarded as an attempt to show only an aspect of how decolonisation can occur. This considers the role of what is being taught in the classroom.

Interestingly, the students who participated in the study acknowledge the role of existing teaching as needed in informing their learning experience. The call by the students was rooted in the equality of knowledge (Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Smit, 2017). In this the students argued for the deliberate introduction of their own super heroes and their stories to the learning experience to be equally important to what is already being taught. In this the students could also be calling for a level of caution and balance in promoting aspects of a decolonised curriculum (Hungwe & Ndofirepi, 2021; Moncrieffe et al., 2020).

The study made some significant contributions. Firstly, through its illustrative findings of the need for super heroes and stories, the study answered calls to locally and internationally understand issues related to decolonisation (Aman, 2018; Hlatshwayo et al., 2022). Secondly, in giving voice to the students and the call for a decolonised curriculum, this could be part of disrupting the dominant logic characterising academia (Martin et al., 2020). Finally, through its findings the study also argued for a student-centred approach - especially regarding issues related to the decolonisation of the curriculum (Arday et al., 2021). The findings of the need for super heroes and their stories relatable to student potentially illustrate some crucial identity work (Cummings et al., 2018) in which lecturers like me are being informed of the importance of being mindful with regard to the issues and contexts in which the students find themselves (Kiguwa & Segalo, 2018). Furthermore, it is also being mindful of the need for relatedness to curriculum issues and knowledge generation (Agherdien et al., 2022).

The study has some implications. Firstly, in keeping with the ideals of the African university argued by Waghid (2021), the findings can be helpful to such ideals. In reflecting on my work as a lecturer, the call is for deliberateness in the content that I use in teaching students. From the findings of this study, the role of super heroes and their stories become essential. For the strategic management course a balance is needed in exposing students to relatable content from their contexts as part of their learning. This could align with what Canham (2018:319) refers to as the call for a "praxis towards decolonial action", which is illuminated by the findings of this study (Chinyamurindi, 2023).

Some limitations of the study can be noted. The sample consisted of students taking a strategic management course at a rural university in South Africa. In essence, although the findings have the potential to inform a wider audience, caution should be exercised given the focussed nature of the study. Future research could be conducted in other disciplines and improve on the sample issue that could be deemed as a limitation in this study. Future research should also prioritise understanding after the introduction of super heroes and their stories in learning, which could be a sequel to this study and assist to improve aspects of teaching and learning for both the lecturer and the student.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges funding from the Teaching and Learning Centre at the University of Fort Hare.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Aby A 2022. Decolonisation of Architectural history education in India. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 6(3):6-25. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v6i3.268 [ Links ]

Agherdien N, Pillay R, Dube N & Masinga P 2022. What does decolonising education mean to us? Educator reflections. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 6(1):55-78. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v6i1.204 [ Links ]

Ally Y & August J 2018. #Sciencemustfall and Africanising the curriculum: Findings from an online interaction. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):351-359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318794829 [ Links ]

Aman R 2018. Decolonising intercultural education: Colonial differences, the geopolitics of knowledge, and inter-epistemic dialogue. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Arday J, Belluigi DZ & Thomas D 2021. Attempting to break the chain: Reimaging inclusive pedagogy and decolonising the curriculum within the academy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(3):298-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1773257 [ Links ]

Arshad R 2021. Decolonising the curriculum - how do I get started? Times Higher Education, 14 September. Available at https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/decolonising-curriculum-how-do-i-get-started. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Barnes BR 2018. Decolonising research methodologies: Opportunity and caution. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):379-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318798294 [ Links ]

Bell GG & Rochford L 2016. Rediscovering SWOT's integrative nature: A new understanding of an old framework. The International Journal of Management Education, 14(3):310-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijme.2016.06.003 [ Links ]

Bourdieu P 1982. Les rites comme actes d'institution [Rites as acts of institution]. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 43:58-63. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1982.2159 [ Links ]

Brandner A & Cummings SJR 2017. Agenda knowledge for development: Strengthening Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Vienna, Austria: Knowledge for Development Partnership. [ Links ]

Campano G 2007. Immigrant students and literacy: Reading, writing, and remembering. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Canham H 2018. Theorising community rage for decolonial action. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):319-330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318787682 [ Links ]

Chambers D & Buzinde C 2015. Tourism and decolonisation: Locating research and self. Annals of Tourism Research, 51:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.12.002 [ Links ]

Chang B 2013. Voice of the voiceless? Multiethnic student voices in critical approaches to race, pedagogy, literacy and agency. Linguistics and Education, 24(3):348-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2013.03.005 [ Links ]

Chinyamurindi WT 2023. Perceptions of what decolonisation means: An exploratory study amongst a sample of rural campus students. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(3):59-72. https://doi.org/10.20853/37-3-4852 [ Links ]

Coetzer A & Sitlington H 2014. Using research informed approaches to Strategic Human Resource Management teaching. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3):223-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijme.2014.06.003 [ Links ]

Crilly J, Panesar L & Suka-Bill Z 2020. Co-constructing a liberated / decolonised arts curriculum. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 17(2): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.17.2.9 [ Links ]

Cummings S, Regeer B, De Haan L, Zweekhorst M & Bunders J 2018. Critical discourse analysis of perspectives on knowledge and the knowledge society within the Sustainable Development Goals. Development Policy Review, 36(6):727-742. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12296 [ Links ]

Dawson MC 2020. Rehumanising the university for an alternative future: Decolonisation, alternative epistemologies and cognitive justice. Identities, 27(1):71-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2019.1611072 [ Links ]

De Beer JJ & Kriek J 2021. Insights provided into the decolonisation of the science curriculum, and teaching and learning of indigenous knowledge, using Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(6):47-63. https://doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4217 [ Links ]

De Oliveira Andreotti V, Stein S, Ahenakew C & Hunt D 2015. Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1):21-10. Available at https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/22168/18470. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

De Paula Arruda Filho N & Przybylowicz Beuter BS 2020. Faculty sensitization and development to enhance responsible management education. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1):100359. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijme.2019.100359 [ Links ]

Foucault M 1970. The archaeology of knowledge. Social Science Information, 9(1):175-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847000900108 [ Links ]

Giancarlo A 2020. Indigenous student labour and settler colonialism at Brandon Residential School [Special section]. The Canadian Geographer, 64(3):461-474. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12613 [ Links ]

Gleason T & Franklin-Phipps A 2019. Curriculum, empiricisms, and post-truth politics. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 34(3):41-54. Available at https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/view/825. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Godsell SD 2021. Decolonisation of History assessment: An exploration. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(6):101-120. https://doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4339 [ Links ]

Guba EG & Lincoln YS 1981. Effective evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Hassan SL 2022. Reducing the colonial footprint through tutorials: A South African perspective on the decolonisation of education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(5):77-97. https://doi.org/10.20853/36-5-4325 [ Links ]

Heleta S 2016. Decolonisation of higher education: Dismantling epistemic violence and Eurocentrism in South Africa. Transformation in Higher Education, 1(1):a9. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v1i1.9 [ Links ]

Herman ES & Chomsky N 1988. Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Hlatshwayo MN, Adendorff H, Blackie MAL, Fataar A & Maluleka P (eds.) 2022. Decolonising knowledge and knowers: Struggles for university transformation in South Africa. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hungwe JP & Ndofirepi AP 2021. A critical interrogation of paradigms in discourse on the decolonisation of higher education in Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(3):54-71. https://doi.org/10.20853/36-3-4587 [ Links ]

Kessi S & Boonzaier F 2018. Centre/ing decolonial feminist psychology in Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):299-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318784507 [ Links ]

Kiguwa P & Segalo P 2018. Decolonising Psychology in residential and open distance e-learning institutions: Critical reflections. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):310-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318786605 [ Links ]

Laakso LH & Hallberg Adu K 2023. 'The unofficial curriculum is where the real teaching takes place': Faculty experiences of decolonising the curriculum in Africa. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01000-4 [ Links ]

Leibowitz B 2017. Power, knowledge and learning: Dehegomonising colonial knowledge. Alternation Journal, 24(2):99-119. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2017/v24n2a6 [ Links ]

Lyons H, Bike DH, Johnson A & Bethea A 2012. Culturally competent qualitative research with people of African descent. Journal of Black Psychology, 38(2):153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798411414019 [ Links ]

Madhav N & Baron P 2022. Curriculum transformation at a private higher educational institution: An exploratory study on decolonisation. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 6(3):26-18. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v6i3.267 [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres N 2007. On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21 (2-3):240-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548 [ Links ]

Manathunga C 2020. Decolonising higher education: Creating space for Southern sociologies of emergence. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 4(1):4-25. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v4i1.138 [ Links ]

Manathunga C, Qi J, Raciti M, Gilbey K, Stanton S & Singh M 2022. Decolonising Australian doctoral education beyond/within the pandemic: Foregrounding Indigenous knowledges [Special issue]. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 6(1):112-137. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v6i1.203 [ Links ]

Martin B, Stewart G, Watson BK, Silva OK, Teisina J, Matapo J & Mika C 2020. Situating decolonization: An Indigenous dilemma. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(3):312-321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1652164 [ Links ]

Matthews S 2021. Decolonising while white: Confronting race in a South African classroom. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(7-8):1113-1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1914571 [ Links ]

Mbembe A 2015. Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. Available at https://wiser.wits.ac.za/sites/default/files/private/Achille%20Mbembe%20-%20Decolonizing%20Knowledge%20and%20the %20Question%20of%20the%20Archive.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2022. [ Links ]

Mbembe AJ 2016. Decolonizing the university: New directions. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 15(1):29-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022215618513 [ Links ]

McCormack C 2000. From interview transcript to interpretative story: Part 1-Viewing the transcript through multiple lenses. Field Methods, 12(4):282-297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0001200402 [ Links ]

Moncrieffe M, Race R & Harris R 2020. Decolonising the curriculum [Special issue]. Research Intelligence, 142:9. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340870420_Decolonising_the_Curriculum_-_Transnational_Perspectives_Research_Intelligenc e_Issue_142Spring_2020. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Msila V (ed.) 2017. Decolonising knowledge for Africa 's renewal: Examining African perspectives and philosophies. Randburg, South Africa: KR Publishing. [ Links ]

Msila V 2023. On relevance, decolonisation and community engagement: The role of university intellectuals. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(1):20-37. https://doi.org/10.20853/37-1-5666 [ Links ]

Nachmias FC & Nachmias D 1996. Research methods in the social sciences (5th ed). New York, NY: Worth. [ Links ]

Napshin SA & Marchisio G 2017. The challenges of teaching strategic management: Including the institution-based view. The International Journal of Management Education, 15(3):470-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2017.07.004 [ Links ]

Okumus F & Wong KKF 2005. In pursuit of contemporary content for courses on strategic management in tourism and hospitality schools. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24(2):259-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.06.009 [ Links ]

Olivier B 2018. Parsing "decolonisation". Phronimon, 19:1-15. https://doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/3064 [ Links ]

Pajares F, Prestin A, Chen J & Nabi RL 2009. Social cognitive theory and media effects. In RL Nabi & MB Oliver (eds). The Sage handbook of media processes and effects. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Available at https://scholarworks.wm.edu/bookchapters/3?utm_source=scholarworks.wm.edu%2Fbookchapters%2F 3&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Accessed 12 May 2022. [ Links ]

Ratele K, Cornell J, Dlamini S, Helman R, Malherbe N & Titi N 2018. Some basic questions about (a) decolonizing Africa(n)-centred psychology considered. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(3):331-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318790444 [ Links ]

Smagorinsky P 2011. Vygotsky and literacy research: A methodological framework. Boston, MA: Sense. [ Links ] Smit JA 2017. #DecolonialEnlightenment and education. Alternation Journal, 24(2):253-312. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2017/v24n2a13 [ Links ]

Smith T 2016. Make space for indigeneity: Decolonizing education. SELU Research Review Journal, 1(2):49-59. Available at https://selu.usask.ca/documents/research-and-publications/srrj/SRRJ-1-2-Smith.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2023. [ Links ]

Thornhill H, Clare L & May R 2004. Escape, enlightenment and endurance: Narratives of recovery from psychosis. Anthropology & Medicine, 11(2):181-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470410001678677 [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Waghid Y 2021. Decolonising the African university again. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(6):1-4 https://doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4875 [ Links ]

Received: 16 April 2018

Revised: 21 December 2018

Accepted: 4 August 2023

Published: 31 August 2023