Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 no.2 Pretoria Mai. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n2a2114

ARTICLES

Exploring the resonance between how mentor teachers experienced being mentored and how they mentor pre-service teachers during teaching practice

Koray KasapogluI; Bulent AydogduII; Ozgun Uyanik AktulunIII

IDepartment of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, Afyon Kocatepe University, Afyonkarahisar, Türkiye kasapoglu@aku.edu.tr

IIDepartment of Science and Mathematics Education, Faculty of Education, Afyon Kocatepe University, Afyonkarahisar, Türkiye

IIIDepartment of Primary Education, Faculty of Education, Afyon Kocatepe University, Afyonkarahisar, Türkiye

ABSTRACT

With the study reported on here we aimed to explore and compare the experiences of pre-service teachers with their mentor teachers and of mentor teachers with their own mentor teachers when they were pre-service teachers. The design of this qualitative research was narrative inquiry. The study group consisted of senior pre-service pre-school teachers taking the Teaching Practice I course (n = 8) in the Faculty of Education at a state university and their mentor teachers (n = 4) teaching in public kindergartens. Qualitative data was collected through individual narrative interviews with pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers. The data was subjected to content analysis using inductive coding. Three themes emerged from the content analysis: (1) mentoring experiences of pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers, (2) mentoring memories of pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers, and (3) wishes of pre-service teachers and of their mentor teachers about mentoring. The most striking finding of this research was that the memories and wishes of pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers about mentoring were similar. The findings of this research are anticipated to bring about different perspectives and contribute to the content and effectiveness of teaching practice courses.

Keywords: mentor teacher; mentoring; narrative inquiry; pre-service teacher; teaching practice

Introduction

The teaching practice course allows pre-service teachers to have field-based learning experiences providing them with opportunities to serve beside mentor teachers and develop instructional skills under the dual guidance of a mentor teacher and a teacher educator (Kennedy & Lees, 2014, cited in Lees & Kennedy, 2017). Pre-service teachers may lack knowledge of how to use various teaching methods and assessment strategies effectively (Matoti & Odora, 2013). For this reason, teaching practice, as a critical element of teacher education, enhances pre-service teachers' experiences before starting in the profession (Mudzielwana & Maphosa, 2014). At this stage, which is the beginning of the teaching experience, pre-service teachers do several practices to improve their teaching skills and expand their knowledge about effective teaching, and they learn the teaching profession by doing and experiencing (Collinson, Kozina, Lin, Ling, Matheson, Newcombe & Zogla, 2009). In the teaching practice course, effective mentor teacher guidance is needed to maximise the achievements that pre-service teachers gain in practice (Ehrich, Hansford & Tennent, 2004; Hobson, Ashby, Malderez & Tomlinson, 2009). The effectiveness of mentor teacher guidance depends on the mentor teacher's roles and qualifications.

Literature Review

From the literature it is clear that mentor teachers who lack adequate characteristics do not always lead analysis, reflection, and development of pre-service teachers. The main problems reported in studies are mentor teachers failing to provide pre-service teachers with adequate support and feedback (Eraslan, 2009; Pierce & Peterson Miller, 1994), imposing their own teaching styles (Beck & Kosnik, 2000; Okan & Yildirim, 2004), not giving advice and suggestions (Vásquez, 2004), not valuing pre-service teachers as colleagues (Schoeman & Mabunda, 2012), being absent from classrooms (Eraslan, 2009; Ravhuhali, Lavhelani, Mudzielwana, Mulovhedzi & Nendauni, 2020), the lack of knowledge and communication skills (Kudu, Özbek & Bindak, 2006; Özmen, 2008; Ravhuhali et al., 2020), their being older (Ravhuhali et al., 2020), their inflexibility regarding teaching and assessment (Heeralal & Bayaga, 2011), and the negative attitudes of school administrators, mentor teachers and students (Demir & Çamli, 2011; Òzdaç, 2018).

The problems related to mentoring mentioned above are also experienced in Türkiye, which is why we embarked on this study. Kasapoglu (2015) reviewed 36 studies on school experience and practice teaching in Türkiye and points out that 22 of them included negative views on school experiences and practice teaching reported by stakeholders. Ineffective mentoring, the lack of interaction between mentors and mentees, poor consideration of practice teaching, and mentor teachers ' lack of awareness about the purpose and content of school experiences and practice teaching seemed to be some of the drawbacks of apathetic mentor teachers and teacher educators (Kasapoglu, 2015). Pre-service teachers are disappointed when they realise that mentor teachers are not competent enough to teach them how to teach. Therefore, planning effective teaching practice is of great significance (Du Plessis, 2013). Effective mentor teachers are individuals who are positive role models, who collaborate with and motivate pre-service teachers and act as mentors, coaches, and friends (Zachary, 2002). Mentor teachers should be individuals who choose to be positive models instead of directing pre-service teachers (Acheson & Gall, 1997), are willing to mentor (Gareis & Grant, 2014), and who possess good communication skills (Trubowitz & Robins, 2003).

Chang-Kredl and Kingsley (2014) state that pre-service teachers' positive school memories result in them imitating their former teachers, while negative school memories may evoke a desire to reverse these experiences. Additionally, pre-service teachers' past experiences and feelings shape their current and future self-perceptions, and accordingly, teaching behaviour (Chang-Kredl & Kingsley, 2014). Miller and Shifflet (2016) state that memories based on teaching practice generally had much stronger effects than the course content; pre-service teachers connected what they experienced in school with effective teaching practices done in the course, and those memories affected their future vision as teachers. From the literature it is clear that pre-service teachers' memories about their past are effective in constructing their teacher identities, and accordingly, the way that they regard themselves as teachers. Furthermore, there is a significant relationship between positive memories about personal and professional characteristics of mentor teachers and the views of pre-service teachers on the ideal teacher (Pellikka, Lutovac & Kaasila, 2018). Similarly, positive and negative experiences of pre-service teachers with mentor teachers during teaching practice might create their memories of mentoring in time.

Real or imagined memories usually relate to narratives, which are often largely in the past tense, spoken and contain a chronological sequence of events (McCabe, 2008). The definition of narrative emphasises the contextual aspect of oral stories that are told to particular listeners to have them create meaning from such stories (Kohler Riessman, 2008). As a cognitive bridge between past and present is established via memories, it is necessary to reveal and analyse pre-service teachers' and mentor teachers' memories based on their experiences (Balli, 2011). This is related to temporality, one of three commonplaces of narrative inquiry, within which field texts, namely, data composed from their narratives, are considered (Clandinin & Caine, 2008). Temporality directs attention to experiences that participants gain through multiple interactions with others over time and reflections they make on and of their past experiences (Clandinin & Caine, 2008). However, the bridge is not only cognitive. Other commonplaces of narrative inquiry are sociality and place (Clandinin & Caine, 2008). Sociality draws attention inward to the emotions, moral disposition, and thoughts of participants and outward to events, people and objects. Place is about the places where the experiences were lived and told.

Carr (1986) associates the ternary structure of time (past-present-future) with three critical dimensions of narrative inquiry. In other words, the past transmits meaning, the present transmits value, and the future transmits intention. Thus, narrative inquiry consists of significance, value and intention (cited in Connelly & Clandinin, 1990). With this research we, therefore, encouraged participants to remember the past (memories), live the present (experiences), and imagine the future (wishes).

Mentor teachers' and pre-service teachers' memories of the teaching practice course may affect their current and future mentoring behaviour. Mentor teachers and pre-service teachers might learn lessons from the past, put those lessons into their current practices and may guide their future actions. The findings in our research might contribute to the growth of pre- and in-service teachers' reflective mentoring skills. Both mentor teachers and pre-service teachers will notice the need of being reflective mentors who "critically reflect upon their own practice to further develop their skills and understanding of different mentoring approaches, drawing from other mentors, their supervisor and from other helping professions" (Merrick & Stokes, 2003 :para. 33). It is thought that studies related to pre-service teachers' and their mentor teachers' memories of mentoring will bring about different perspectives and will contribute to the content and effectiveness of the teaching practice course. In addition, it is anticipated that pre-service teachers receiving positive mentoring experiences will help their students acquire knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and competences to progress into higher education and the business world, and thus, contribute to the economic development of society at a national level (Mukeredzi, Mthiyane & Bertram, 2015). Therefore, in this study, we aimed to explore and compare pre-service teachers' experiences with those of their mentor teachers and their mentor teachers' experiences with those of their own mentor teachers when they were pre-service teachers. For this purpose, answers to the following research questions were sought:

1) What are the mentoring experiences, memories and wishes of

a) in-service teachers when they were pre-service teachers?

b) pre-service teachers?

2) How do in-service teachers' memories of mentoring affect their present mentoring behaviour?

Theoretical Framework

Mentoring

The term "mentor" has several definitions, which range from someone who helps mentees pursue a career, to someone who teaches mentees about life, from a regular classroom teacher who does what s/he always does, to a developmental guide who can work without focusing on a specific field (Daloz, 1983). Mentoring is effective in professional development programmes, especially when it meets instructional and content needs of teachers (Nel & Luneta, 2017). Mentoring is an essential tool that fosters learning of pre-service, novice and in-service teachers (Sibanda & Jawahar, 2012). During teaching practice, pre-service teachers receive feedback from the mentor teacher and teacher educator regarding problems, teacher-child interaction, and inquiry-based and reflective learning (Linn & Jacobs, 2015). Mentoring is also effective in increasing learners' success in the classroom, thus allowing them to access the opportunities for further education and employment and ultimately making a contribution to national economic development (Mukeredzi et al., 2015).

Mentoring is a complex task affected by the personal characteristics of the mentor teacher and the novice teacher, the needs of the novice teacher, and the relationships between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher. Mentoring is multifaceted despite various mentoring schemes and approaches. Indeed, there is no simple prescription for effective mentoring (Martin, 1996). Although an agreed model for mentoring does not exist, there is an urgent need to work towards a common understanding of roles and responsibilities (Martin, 1996). As a theoretical framework for this research, Daloz's structure based on modes that mentors normally adopt, was helpful (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). Daloz (1986) suggests that mentors do three things: they support, challenge and give vision (cited in Martin, 1996).

Support is defined as "acts through which the mentor affirms the validity of the student' s present experience" and "attempts to bring her boundaries into congruence with his [the student's]" (Daloz, 1986:212, cited in Martin, 1996). For instance, providing structure to what the novice teacher does or expressing positive expectations might be regarded as support (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). A challenge is where the mentor teacher tries to advance the novice teacher towards her/his own or generalised ideal. Taking up a contrasting stance to encourage discussion might be regarded as challenge (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). The third dimension is vision, which inserts challenge and support in a suitable context. Novice teachers use vision as a means to achieve goals. The mentor teacher should create a context of expectations, but what is more vital, is having a general vision rather than a specific one (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). The mentor provides vision by acting as a guide or a role model by encouraging discussion about the future of a mentee (Bower, 1998). Mentoring requires a good mix of support and challenge. The desire to get a good mix of support and challenge to keep novice teachers moving forward is a guarantee of success itself (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). By balancing support, challenge and vision, the mentor builds the tension necessary for change and development (Widick & Simpson, 1978, cited in Bower, 1998).

Daloz (1986) describes a model of mentor-mentee interaction that is effective in helping adults through transition (cf. Figure 1). He reports that effective mentor-mentee relationships balance the following elements: support, challenge, and a vision of the mentee' s future career (cited in Bower, 1998).

This model provides the mentor with a helpful framework for thinking about relationships with the mentee regarding their current developmental status and how to strike a fit balance between support and challenge, which will naturally place the mentee in the growth quadrant. This is the result of suitably high challenge and suitably high support (Schofield, 2019) as striking a balance between support and challenge in mentoring is essential. An overly supportive mentor may induce learned helplessness and dependency in the mentee, thereby restraining development. Appropriately high support and appropriately high challenge are effective (Daloz, 1986, cited in Schofield, 2019). The quadrant representation helps mentors think about how their own behaviour could hinder or advance development (Schofield, 2019).

The novice teacher will make little progress with little support and little challenge (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996) and maintain the status quo. That is, the novice teacher will not be required to spend any energy to change what s/he is doing (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). It accelerates very limited development, and the mentor-mentee relationship can be considered unfocused due to inadequate planning and analysis (Schofield, 2019). With little or no support or with too much challenge the novice teacher will likely withdraw because s/he cannot cope with the challenge (Daloz, 1986, cited in Martin, 1996). The novice teacher will not learn at all and will physically or psychologically retreat from the mentoring relationship (Schofield, 2019). With too much support and little challenge, the novice teacher becomes dependent on his/her or the mentor's pre-existing ways of teaching or is forced into a state of learned helplessness and over-reliance on others, which then harms the development of personal resilience (Schofield, 2019).

Methodology

Research Design

The design of this qualitative research aiming at exploring and comparing pre-service teachers' and their mentor teachers' experiences of mentoring was narrative inquiry. Narrative inquiry is "... the study of experience as story, then, is first and foremost a way of thinking about experience. Narrative inquiry as a methodology entails a view of the phenomenon. To use narrative inquiry methodology is to adopt a particular view of experience as phenomenon under study" (Connelly & Clandinin, 2006:477). Narrative inquiry, within which experience is studied and understood narratively, requires researchers to consider relational knowing and being, paying attention to the art of and within experience, and being sensitive to common stories that bring people together (Caine, Estefan & Clandinin, 2013). Connelly and Clandinin (2006) describe three dimensions of narrative inquiry, namely, temporality, sociality, and place. Considering temporality, narrative researchers describe events, people, and objects with past, present, and future (Clandinin & Rosiek, 2007). Narrative inquiry always tries to understand people, places, and events in progress because people and events always own past, present, and future (Clandinin, Pushor & Murray Orr, 2007). Considering sociality, narrative researchers are simultaneously concerned with personal and social conditions (Clandinin & Rosiek, 2007). Personal conditions are "the feelings, hopes, desires, aesthetic reactions, and moral dispositions of the person" and social conditions are "the existential conditions, the environment, surrounding factors and forces, people and otherwise, that form the individual's context" (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, cited in Clandinin & Rosiek, 2007:69). The interaction between participant and inquirer is another important dimension of sociality. Narrative inquirers always have an inquiry relationship with the lives of participants (Clandinin & Rosiek, 2007). Considering place as the third dimension, narrative researchers recognise that all events happen in some place of which the impact on lived and told experiences is important (Clandinin & Rosiek, 2007).

Participants

Nowadays, pre-school teachers are faced with raising standards and expectations that demonstrate what they should know and do to foster children's early development and learning. This has led to a dramatic increase in the quantity and quality of mentoring opportunities being offered at pre-school level (Whitebook & Bellm, 2014). For this reason, the pre-school level was chosen as area of enquiry for this research. Mentoring can be considered to become essential in pre-school teacher education. Therefore, the study group consisted of senior (fourth-year) pre-service pre-school teachers taking Teaching Practice I (n = 8) offered in the last year of their teacher education programme at the Faculty of Education at a state university, and their mentor teachers teaching in public kindergartens (n = 4). The majority of the participants were female (n = 7). The pre-service teachers were on average 22 years old and their mean cumulated grade point average was 3.18 over 4.00. The pre-service teachers could thus be considered to demonstrate satisfactory academic performance. The mentor teachers participating in this research had an average of 12 years of teaching experience. Participants were determined by purposeful sampling methods such as criterion sampling and convenience sampling. In selecting the mentor teachers, criterion sampling was employed. In criterion sampling, individuals, groups, or settings that meet certain criteria are selected (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007). A further criterion was that the pre-service teachers should have graduated from an undergraduate pre-school teacher education programme offered at a faculty of education. In selecting the pre-service teachers, convenience sampling was also used because they were the mentees of the mentor teachers participating in the research. In convenience sampling, individuals or groups that are available and eager to participate are selected (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007).

Data Collection Tools

For narrative inquiry, telling of stories, listening to individuals telling their stories is mostly used as point of departure, and interviews and conversations or interviews as conversations are the data collection techniques which are most commonly used (Clandinin & Caine, 2008). Qualitative data was collected through individual narrative interviews with pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers. Narrative interviews as a strong technique of data collection in qualitative studies aim at creating content in which subjective experiences are conveyed (Muylaert, Sarubbi, Gallo, Neto & Reis, 2014). As stated by Connelly and Clandinin (1990), unstructured interview is one of the data collection tools in narrative inquiry. In unstructured interviews, researchers make transcripts that become part of the continuous narrative record (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990). Unstructured individual interviews were conducted face-to-face. Both mentor teachers and pre-service teachers were asked the same question, "Tell me about unforgettable moments you had with your mentor teacher in practice school." They were also asked questions like, "what happened then?" rather than "why?" (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, 2016:632).

Interviews with pre-service teachers conducted after they had completed Teaching Practice I lasted an average of 20 minutes, and interviews with mentor teachers lasted an average of 17 minutes.

Data Analysis

Through word processing software, all the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The data was analysed using inductive coding (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 2002; Yildirim & Çimçek, 2016) to identify "core consistencies and meanings" (Patton, 2002:453). We did not develop or use any predefined list of codes and themes and performed content analysis after data collection. In content analysis, known as latent analysis (Bengtsson, 2016), the related codes obtained from the interview data was sorted into appropriate themes in light of the research questions.

Credibility of Data

Purposeful sampling, expert review, and thick descriptions were the strategies used to ensure trustworthiness of the data. The credibility of the interview data was supported by direct quotations. The interview data was collected via voice recorder, and these recordings were analysed by transcribing them on computer without any manipulation. Recording of interviews with a voice recorder prevented data loss. The anonymity of the participants was ensured by allocating pseudonyms to each (such as Ebbie, Adam). Interview data was coded to be conceptualised by us as co-coders, and we frequently discussed the initial codes based on the purpose of the research in order to reach consensus. We then collated the agreed-on codes in themes to represent the findings.

Findings

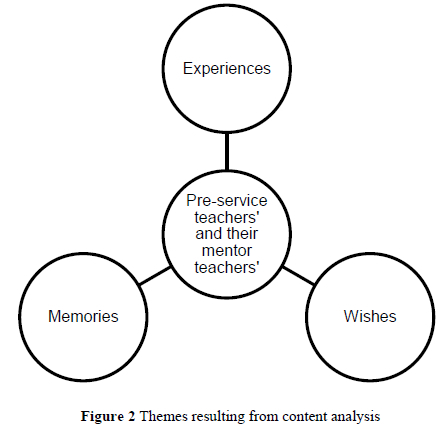

From the analysis of the qualitative data collected from narrative interviews, three themes were obtained (cf. Figure 2).

Themes emerging from the content analysis were (1) the experiences of pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers in practice schools, (2) the memories of pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers in practice schools, and (3) the wishes of pre-service teachers and of their mentor teachers about their own mentor teachers.

Experiences of Pre-service Pre-school Teachers and Mentor Teachers related to Mentoring in Practice Schools Experiences of pre-service pre-school teachers related to mentoring in practice schools

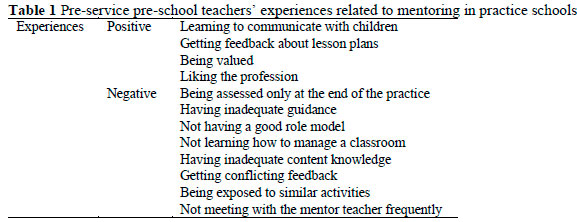

The pre-service pre-school teachers' experiences related to mentoring in practice schools were categorised as positive and negative experiences (cf. Table 1).

Among the positive experiences that pre-service teachers had experienced in practice schools were learning how to communicate with children, getting feedback from the mentor teacher about the activity plans, appreciation by the mentor teacher, and the mentor teachers endearing the profession to pre-service teachers.

For example, in communication with children ... the teacher helped me communicate with the children (Emily).

I did the practice on Fridays every other week. I was sending the plan of the day to both my teacher educator and mentor teacher. They provided me with feedback. Then I re-arranged my activities (Cindy).

I do not think they are against us because when we went there, our teacher said, 'We missed you very much girls. You were conspicuous by your absence. ' I think our teacher valued us also with the effect that we were not in any negative situation. (Sally)

Our teacher internalised us and endeared the profession to us. There was no problem. It was good for the first semester (Adam).

Regarding the negative experiences they had in practice schools, pre-service teachers mentioned the fact that the mentor teachers did not do assessment during the teaching practice process, did not guide effectively, did not make any contributions in terms of classroom management and content knowledge, did not provide feedback through consistent explanations, did not do a wide variety of activities, did not meet with pre-service teachers much, and did not act as good role models.

As you know, we did assessment at the end of the practice; the teacher gave the feedback I thought she would give every week all at once in the final evaluation. For example, if she had told me she looked for a science activity every week, I would have arranged my course accordingly. I do not think it will make any contribution when these things are said at the end, it is too late. (Betty) We started practice teaching in the third- and fourth-year of our teacher education programme. In these periods of time, we were developing, implementing our activity and turning back. What are you going to do this week? What are you going to do next week? There was no positive or negative feedback at the end of the activities. We were not sure of ourselves. ... Based on my own experience, I would like them to give us some guidance by the end of the day. (Bella)

It is classical in teaching; being a role model. I do not think her feedback will be useful as she did not do anything to be a role model for us (Emily). I made paper paste for an activity. ... The mentor teacher said the paper paste was her favourite kneading material. I said I loved it, too. . Then I told the children how I made the paste. The mentor teacher was not in the classroom at this time. Then she came and asked me if I told how to make the paste. When I said I did, she wanted me to tell again. I started telling it again. Meanwhile she took notes. I was thinking if she loved it so much then why did she not use it. I never saw children playing with a kneading material during the practice. (Penny)

The assessment was directly result-oriented. This surprised me. She said she looked for a science activity every week. I did every week, but not always as experiment. She considered I did not . (Betty). Our teacher this year was not very active. When we went to the classroom for the first time for observation, it was like this: sing a little, read a story then occupy children with painting. As it was only this much, there was nothing we could not forget. (Emily)

We did not have much communication. Yes, as I said, she was not in the classroom for the most of the semester. We were going there and she was coming here. I heard she was coming to your class. Therefore, I can say we could not communicate much. (Cindy)

Experiences of mentor teachers related to mentoring in practice schools when they were pre-service teachers

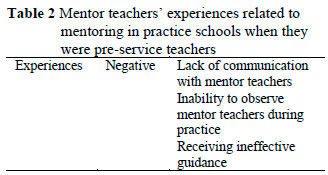

The mentor teachers' experiences of practice schools when they were pre-service teachers are categorised as negative experiences (cf. Table 2).

It was noteworthy that the mentor teachers' experiences of practice schools were mostly negative. Mentor teachers listed the following negative experiences of their time in practice school: a lack of communication with the mentor teacher, not being able to observe the teacher during activities, and not receiving effective guidance from the mentor teacher.

... Therefore, we always arrived 15-20 minutes in advance. For example, teacher would come, leave her bag and get interested in children, but she did not greet us or say good morning. We practiced for 3 years, they never did. I think this is a deficiency. (Hannah)

I did not experience that but what I experienced was that I could never observe them. ... I could not observe the teachers in the third and fourth grades; I wish I could have observed them. [I wish I could have observed] how to teach, how to read stories, how to teach math, Turkish language, how to ensure discipline in classroom, how to teach a tongue twister and a song. . (Zabrina) . the teachers left us in the classroom and went out, so we did not have a guide. . They did not observe us to tell us our good and bad behaviours. They just left us in the classroom and went out. It was a bad experience for me. (Zabrina)

We discovered that the pre-service pre-school teachers' negative experiences with their mentor teachers were similar to those of their mentor teachers as pre-service teachers; the negative experiences were mostly related to communication, guidance, and observation, which did not change considerably over time. It is thus clear that the mentor teachers mentored the pre-service teachers as they were previously mentored; in other words, mentor teachers neither received nor provided support. They appeared to maintain the status quo in light of the balance between support and challenge (cf. Figure 1 - Daloz's (1986) model cited in Schofield, 2019).

Memories of Pre-service Pre-school Teachers and Mentor Teachers in Practice Schools

Memories of pre-service pre-school teachers in practice schools

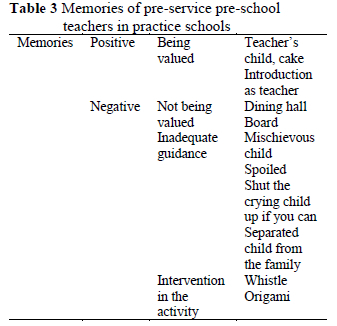

The pre-service pre-school teachers' memories in practice schools are presented as positive and negative memories (cf. Table 3).

While it is understood that the positive memories of the pre-service pre-school teachers in practice schools are generally related to being appreciated, it is noteworthy that their memories were mostly negative.

They made a cake for us in the last week. I actually predicted it.... There were friends from the morning group; they gathered everybody so I understood what was happening. They brought a cake, it was not interesting for me but I liked it. I appreciated it, they wanted to surprise us. It was not a surprise for me, but they valued us. (Adam)

The pre-service pre-school teachers experienced that their mentor teachers did not value them, did not guide them enough, and interrupted them while they were performing their own activities.

It happens this year. ... In the school we went, it was forbidden for us to go to the dining hall with the students. It was an independent kindergarten and I found this very humiliating. It was not a school where I felt like a pre-service teacher. It was disturbing and interesting. ... I do not think we were regarded as pre-service teachers to be frank. They were regarding us as their assistants. (Betty) A negative memory I have is that when we were going to make an activity aboutfamily, we asked the teacher before if there was anybody in the classroom who lost their parents or who hadfamily issues, and she said there was not. Then, we made children draw a picture of their families, and one child started to cry while drawing. I went and asked her why she was crying, and there was only one woman in her picture. I thought the woman in the picture was her mother, then I asked her why she did not draw her father, and she said her parents were divorced. Then, she said she did not want to continue the activity and cried again. I went to the teacher and told this. I asked why she did not tell this situation to us and she said she did not know either. It was weird that she did not know such a thing.... (Ebbie)

I had many memories of my mentor teacher that I did not forget. ... My mentor teacher always intervened in the activity using the whistle and interrupted my activities many times saying 'Let's have fruit, let's go to the dining hall' and so on. I was implementing integrated activities, and during the activity, our mentor teacher kept interrupting us saying the children were overwhelmed and bored. But children were participating in the activity and they were quite pleased. She wanted children to eat some fruit or junk food in the middle of the activity. (Penny)

Memories of mentor teachers in practice schools when they were pre-service teachers

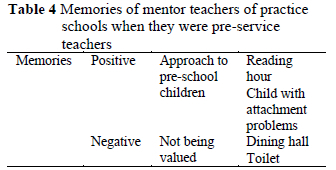

The mentor teachers' memories of practice schools are categorized as positive and negative memories (cf. Table 4).

We understood that the mentor teachers' positive memories mostly related to the approach to pre-school children.

I have never forgotten that moment. The teacher told me to read the children a story. She gave me the story book. I took the book and waited. The teacher made the children sit down. I could not even figure out how to make them sit down. ... Then I started reading Pinocchio. . Then the teacher said I should make them silentfirst. Then she helped me do it. Then I started to read again, but I did not feel confident. I did not know how to read it. The teacher told me to show the pictures to children one by one. This was our deficiency. I remembered as if it had happened yesterday. ... I faced what I did not know that day there. (Zabrina)

We understood that the mentor teachers did not feel valued when they were pre-service teachers.

There is not a very interesting memory. Just now, we can be with children in the dining halls with the pre-service teachers. Back then, they had a very strict rule. They said whoever did the practice would accompany children to wash their hands and go to the dining hall and others would wait in the classroom. Only that pre-service teacher would be given breakfast. We were hurt by this on that day. It was rude like only who did the practice deserved breakfast. I was very sad then. (Hannah) For example, there was one person on guard. On that day, the guard could eat a meal and the others were left out (Nelly).

The results reveal that the negative memories of pre-service pre-school teachers were similar to those held by their mentor teachers when they were pre-service teachers. These feelings were mostly related to feeling undervalued, which did not change substantially over time. The mentor teachers who were not valued as pre-service teacher perpetuated the same and did not value the pre-service teachers that they mentored. In view of Daloz' s (1986, cited in Schofield, 2019) model, the mentor teachers maintained the status quo of support and challenge.

Wishes of Pre-service Teachers about Their Mentor Teachers and of Mentor Teachers about Their Own Mentor Teachers

Wishes of pre-service pre-school teachers about their mentor teachers

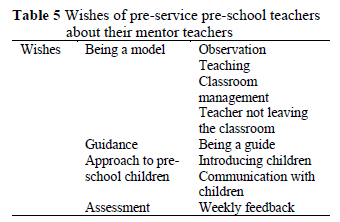

The pre-service pre-school teachers' wishes about their mentor teachers are categorized as being a model, guidance, approach to pre-school children, and assessment (cf. Table 5).

Pre-service teachers wished that the mentor teachers had provided more guidance, showed how pre-school children should be approached and how assessment should be done, thus being better role models.

I would like to observe her. ... She said she wrote her own activities for 2-3 days of the week. I would like to see how she implements her own activities (Cindy).

I am a bit inadequate in the subject of drama and I know it. For example, in the first weeks I implemented a drama activity in Red Crescent week, and it was a disaster. For example, I skipped the warm up. It was confusing. I would like her to contribute something to me in the subject of drama. (Adam)

Generally, I would like her to tell us the characteristics of the children as we met with the children for the first time ... Yes. For example, we had a girl in the classroom with a speaking difficulty. The teacher told this to us only when we noticed it and asked her. This took 2 or 3 weeks. . I would like the teacher to tell me this to facilitate my communication with the child. (Emily) No negative or positive feedback was provided for us. We actually wanted it because we wanted to see our mistakes and we wanted to be appreciated when we did something correctly (Sally).

Wishes of mentor teachers about their own mentor teachers when they were pre-service teachers

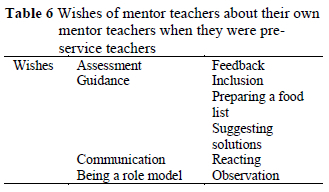

The mentor teachers' wishes about their own mentor teachers are categorised as assessment, guidance, communication, and being a model (cf. Table 6).

The mentor teachers wished that their own mentor teachers had assessed more, had provided more feedback and guidance, and had communicated and observed how they had implemented activities.

I wish they gave us positive feedback. . I wanted to be guided with words like, 'What would you do in this situation? I did these and received positive feedback. You are a student, what would you do? ' But these things never happened. (Hannah) I would like to hear sentences like, ' Do not get me wrong, but you can solve this problem in this way, you need to behave like this. ' We were inexperienced and tried to learn something from the experienced teachers. I would like to hear a sentence like 'Let's try to solve this in this way. ' (Nessa)

We did not react because we were temporarily there. We did not want to cause trouble. . We did not show that we were hurt. . But it was wrong. I wish we told her. Of course, we did not go there to eat, but the tone was wrong. (Hannah) We learned many things in theory, and I wanted them to help us put these in practice. We really needed it. . it would be better if only we could observe them and they guided us in the classroom and if they were present and observed us. (Zabrina)

We noticed that the wishes of the pre-service preschool teachers about their mentor teachers and of the mentor teachers about their own mentor teachers were similar and were mostly related to guidance and assessment; which did not change much over time. Based on this finding, the mentor teachers' and pre-service teachers' expectations from their mentor teachers corresponded. The fact that both pre-service pre-school teachers and mentor teachers wanted to change guidance and assessment indicated that mentoring expectations did not change much over time. Mentor teachers appeared to maintain the status quo in light of Daloz' s (1986, cited in Schofield, 2019) proposed balance of support and challenge.

Conclusions, Discussion, and Implications

Among the positive experiences that pre-service pre-school teachers mentioned were learning from the mentor teachers how to communicate with children, getting feedback from the mentor teacher about their activity plans, appreciation by the mentor teacher, and the mentor teachers endearing the profession to pre-service pre-school teachers. In similar studies, it was emphasised that the relationship established between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers in the teaching practice course was important for the practice to be carried out in a healthy way (Retnawati, Sulistyaningsih & Yin, 2018). Jeriphanos (2017) suggests a symbiotic relationship among and between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers because mentor teachers assist pre-service teachers - especially with scheming, planning, and teaching. Mukeredzi (2013) concludes that the professional development experiences gained by teachers through hands-on classroom practices enhanced their learning. The pre-service teachers emphasised that they expected the mentor teachers to be role models, to support them in the teaching process, to regard them as colleagues, to share their experiences (Aydogdu, 2019), and to provide feedback (Ramazan & Yilmaz, 2017; Yildiz Atlan, Ulutas. & Demiriz, 2018).

The negative experiences of pre-service preschool teachers and of mentor teachers were identical. Mentor teachers listed the negative experiences that they mostly had were a lack of communication with their mentor teachers, not being able to observe how their mentor teachers implemented the activities, and not receiving effective feedback from their mentor teachers. They were primarily concerned with communication, guidance, and observation. The negative experiences of the pre-service pre-school teachers and of mentor teachers did not change dramatically over time. The mentor teachers did not receive or provide support. They appeared to preserve the status quo in light of the balance between support and challenge as proposed by Daloz (1986, cited in Schofield, 2019). We found that pre-service teachers had difficulties in terms of mentoring, supervision, and placement in practice schools (Mokoena, 2017). The inability of pre-service teachers to communicate with mentor teachers may have led to not being aware of their counterparts' expectations regarding teaching practice. If mentor teachers' and the pre-service teachers' expectations do not overlap, this will result in less positive outcomes of teaching practice as well as negative emotions (Hastings, 2010). Kilgour, Northcote and Herman (2015) state that the worst experiences that pre-service teachers remembered were due to problems related to classroom management, planning, communication and learning, which were characterised by emotional distress caused by uncertainty and complexity. Many studies reveal that the problems related to teaching practice were experienced in providing effective guidance and interaction between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers (Baran, Yaçar & Maskan, 2015; Kasapoglu, 2015; Ramazan & Yilmaz, 2017). Robinson (1998) indicates that mentor teachers learned from their own teacher training that welcoming and supporting pre-service teachers were of great significance and that the quality of the interaction between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers had not yet been discussed. Mukeredzi (2017) concludes that collaboration between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers revived mentor teachers' practices and made them more reflective, enthusiastic, and passionate about the work while poor communication and a lack of modelling lessons and objective feedback were non-developmental experiences. Bullough, Young, Birrell, Clark, Egan, Erickson, Frankovich, Brunetti and Welling (2003) argue that negative experiences in mentoring relationships might be prevented through the careful matching of mentors and mentees.

While pre-service pre-school teachers' positive memories about practice schools were related to being valued, it was noteworthy that the pre-service teachers' negative memories were related to feeling undervalued, not being guided effectively, and being prevented from implementing their own activities. The mentor teachers' positive memories of practice schools were mostly related to the approach to preschool children. Yet, the mentor teachers' negative memories of practice schools made them feel undervalued. It was stated that the direct interaction of pre-service teachers with mentor teachers manifested in different ways and was mostly characterised by hierarchy (authority) and power (insecurity) (Rodrigues, De Pietri, Sanchez & Kuchah, 2018). Although mentor teachers who support and guide pre-service teachers and allow them to establish relationships with students by loosening control is desired, the pre-service teachers described their experiences throughout the practice as loneliness, inadequacy, and vulnerability, and it was stated that the pre-service teachers often hid these feelings (Bloomfield, 2010). In many studies it was found that pre-service teachers were not valued as colleagues or teachers in practice schools (Baran et al., 2015; Karasu Avci & Ibret, 2016).

The negative memories recalled by the pre-service pre-school teachers and the mentor teachers were similar because the future is a reflection of the past (Miller, 2017). The lack of lessons learned from the past may have contributed to the fact that mentoring practices did not change over time. Mentor teachers may be consciously or unconsciously imitating their own mentor teachers. This may be due to their inability to think reflectively on mentoring. In addition, they may tend to carry the past, which they thought to be true, to the future without questioning and judging, since they started the profession without having awareness of what an effective mentor or effective mentoring was while they were pre-service teachers. Many mentor teachers received low support and low challenge when they were pre-service teachers years ago. However, our findings reveal that they in turn provided pre-service teachers with low support and low challenge. As a result, the pre-service teachers in our research might have maintained the status quo considering the balance between support and challenge (Daloz, 1986, cited in Schofield, 2019). Pre-service teachers were not sufficiently encouraged to reflect on their existing knowledge and images of teaching, and they did not feel challenged to change what they were doing. The main concern is that pre-service teachers will also provide low support and low challenge to their mentees when they become teachers in the future.

We found that pre-service pre-school teachers' wishes about mentor teachers were related to the mentor teachers' being role models. The pre-service pre-school teachers' memories about mentor teachers influenced their ideas and beliefs about teaching. Based on their observations of mentor teachers' teaching practices, pre-service pre-school teachers created an image in which they played a caring and loving role. Some pre-service pre-school teachers described their mentor teachers as the role models that they wanted to become in the future. Being mentored by mentor teachers who possess effective teacher characteristics, have strong professional knowledge and are innovative teachers may help pre-service teachers change their beliefs about teaching (Aldemir & Sezer, 2009). Sedibe (2014) highlights that mentor teachers play a significant role in helping pre-service teachers develop content knowledge and professionalism. We observed that the wishes of the mentor teachers regarding their own mentor teachers were mostly related to assessment and guidance. One of our findings was that the wishes of pre-service preschool teachers and mentor teachers (e.g. being models) were similar with regard to mentoring. The desire of both pre-service pre-school teachers and mentor teachers to change guidance and assessment if given the opportunity indicated that mentoring expectations did not change significantly over time. As a result, mentor teachers seemed to sustain the status quo in light of the balance between support and challenge (Daloz, 1986, cited in Schofield, 2019). It can be said that the mentor teachers tried to mentor pre-service pre-school teachers as much as they were mentored when they were pre-service teachers. This finding reveals that past experiences of mentoring influence and shape current mentoring experiences. Indeed, many studies (Balli, 2014) reveal that past experiences, memories, observations and apprenticeships may affect pre-service teachers' future practices. Pre-service teachers' past experiences may affect their current views, and their intentions about their future students are mostly based on their past experiences and the desire to relive positive ones and to change negative ones (Randall & Maeda, 2010). However, the data from our study did not resonate with this assertion. Mentor teachers in our research tended to imitate rather than reverse what they had experienced or observed (Chang-Kredl & Kingsley, 2014). This might be because the mentor teachers who participated in this research were not reflective enough. While reflective teachers are teachers who look back and evaluate past events and change their teaching practices and beliefs according to the needs of their students, non-reflective teachers are skilled technicians who have limited skills in making appropriate decisions, considering the results of their actions, and changing their actions (Schon, 1983, 1987, cited in Braun & Crumpler, 2004). In fact, if pre-service teachers are not reflective, it can be envisaged that they will mentor future pre-service teachers in the same way as they were mentored years ago. This problem can be alleviated by developing reflective skills (Kukari, 2004).

As pre-service teachers are expected to advance towards the uncertainty and complexity of schools from university, it is important that they are trained to criticise and reflect on themselves, cope with emotional responses, and learn things from critical events they had experienced in the teaching process (Kilgour et al., 2015). Teacher educators should consider the pre-service teachers' memories about school, discuss and associate the possible conflicts between personal experiences and effective practices in order to relate the ideas obtained from the observation apprenticeship with the appropriate teaching practices (Miller & Shifflet, 2016). Teacher educators should realise that lecturing theories does not help learning to teach and create moments where theories can be presented in a realistic and memorable way (Loughran, Brown & Doecke, 2001). Furthermore, Baartman (2020) suggests that teacher educators should spend more time in schools running in-service workshops on mentoring skills and mentor roles to help teachers become qualified mentors who perform their duties exceptionally well while taking ownership and responsibility for the teacher training programme. According to Mukeredzi (2017), mentor teachers can be better prepared to support not only pre-service teachers, but also novice teachers if they experience mentoring practices and are assisted with in-depth continuous training. Hence, mentor teachers will help pre-service teachers become professionally qualified to contribute to the economic resources of a country (Mukeredzi et al., 2015).

In this research mentor teachers' and pre-service teachers' memories about mentoring were examined and compared through individual interviews. In future research, data might be collected by mentor teachers and pre-service teachers writing autobiographical or reflective journals about mentoring. Data from such diaries might be used to support interview data and may help with the design of teacher training programmes that will enable pre-service teachers to develop professional identity (Lipovec & Antolin, 2014). The way in which pre-service teachers' personal perspectives develop into professional perspectives can also be understood through the critical reflections (Trotman & Kerr, 2001).

Authors' Contributions

All authors conducted the interviews, analysed the data, wrote the manuscript and reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 26 August 2020; Revised: 16 June 2022; Accepted: 21 December 2022; Published: 31 May 2023.

References

Acheson KA & Gall MD 1997. Techniques in the clinical supervision of teachers: Preservice and inservice applications (4th ed). New York, NY: Longman. [ Links ]

Aldemir J & Sezer O 2009. Early childhood education pre-service teachers' images of teacher and beliefs about teaching [Special issue]. Inonu University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 10(3):105-122. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/92284. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Anderson C & Kirkpatrick S 2016. Narrative interviewing. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(3):631-634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0222-0 [ Links ]

Aydogdu B 2019. Fen bilgisi ögretmen adaylarinin ögretmenlik uygulamasi dersine yönelik görücleri [Pre-service science teachers' views about the teaching practice course]. In AM Demirkiran, UK Demirutku, ÜO Yilmaz, A Araci Iyiaydin, Y Kamaci & Z Yeler (eds). Tam metin bildiriler kitabt 3. Uluslararasi Ögretmen Egitimi ve Akreditasyon Kongresi [Proceedings from the III International Teacher Education and Accreditation Congress]. Istanbul, Turkey: Ögretmenlik Egitim Programlari Degerlendirme ve Akreditasyon Dernegi (EPDAD). Available at https://bulut.epdad.org.tr/index.php/s/nRxERKLzG9CJUg5. Accessed 18 November 2020. [ Links ]

Baartman N 2020. Challenges experienced by school-based mentor teachers during initial teacher training in five selected schools in Amathole East District. e-Bangi: Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 17(4):149-161. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/322855695.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Balli SJ 2011. Pre-service teachers' episodic memories of classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.tate.2010.08.004 [ Links ]

Balli SJ 2014. Pre-service teachers' juxtaposed memories: Implications for teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 41(3):105-120. [ Links ]

Baran M, Yaçar Ç & Maskan A 2015. Evaluation of prospective physics teachers' views towards the teaching practice course. Dicle Üniversitesi Ziya Gökalp Egitim Fakiiltesi Dergisi, 26:230-248. [ Links ]

Beck C & Kosnik C 2000. Associate teachers in pre-service education: Clarifying and enhancing their role. Journal of Education for Teaching, 26(3):207-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/713676888 [ Links ]

Bengtsson M 2016. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2:8-14. https://doi.org/10.10167j.npls.2016.01.001 [ Links ]

Bloomfield D 2010. Emotions and 'getting by': A pre-service teacher navigating professional experience. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3):221-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.494005 [ Links ]

Bower DJ 1998. Support-challenge-vision: A model for faculty mentoring. Medical Teacher, 20(6):595-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599880373 [ Links ]

Braun JA, Jr & Crumpler TP 2004. The social memoir: An analysis of developing reflective ability in a pre-service methods course. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(1):59-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.09.006 [ Links ]

Bullough RV, Jr, Young J, Birrell JR, Clark DC, Egan MW, Erickson L, Frankovich M, Brunetti J & Welling M 2003. Teaching with a peer: A comparison of two models of student teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(1):57-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00094-X [ Links ]

Caine V, Estefan A & Clandinin DJ 2013. A return to methodological commitment: Reflections on narrative inquiry. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(6):574-586. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2013.798833 [ Links ]

Chang-Kredl S & Kingsley S 2014. Identity expectations in early childhood teacher education: Pre-service teachers' memories of prior experiences and reasons for entry into the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43:27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.005 [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ & Caine V 2008. Narrative inquiry. In LM Given (ed). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n275 [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ, Pushor D & Murray Orr A 2007. Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1):21-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106296218 [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ & Rosiek J 2007. Mapping a landscape of narrative inquiry: Borderland spaces and tensions. In DJ Clandinin (ed). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Collinson V, Kozina E, Lin YHK, Ling L, Matheson I, Newcombe L & Zogla I 2009. Professional development for teachers: A world of change. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(1):3- 19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760802553022 [ Links ]

Connelly FM & Clandinin DJ 1990. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5):2-14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002 [ Links ]

Connelly FM & Clandinin DJ 2006. Narrative inquiry. In JL Green, G Camilli & PB Elmore (eds). Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Daloz LA 1983. Mentors: Teachers who make a difference. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 15(6):24-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1983.10570000 [ Links ]

Demir Ò & Çamli Ò 2011. Schools teaching practice lesson practice problems encountered the investigation of class and opinions of pre-school students: A qualitative study. Journal of Uludag University Faculty of Education, 24(1):117-139. [ Links ]

Du Plessis E 2013. Mentorship challenges in the teaching practice of distance learning students. The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, 8(1):29-43. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/EJC145141. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Ehrich LC, Hansford B & Tennent L 2004. Formal mentoring programs in education and other profession: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4):518-540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X04267118 [ Links ]

Eraslan A 2009. ilkögretim matematik ögretmen adaylarinin 'ögretmenlik uygulamasi' üzerine görüs,leri [Prospective mathematics teachers' opinions on 'teaching practice']. Necatibey Egitim Fakiiltesi Elektronik Fen ve Matematik Egitimi Dergisi, 3(1):207-221. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26625716_Prospective_Mathematics_Teachers'_Opinions_on_Teaching_Practice. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Gareis CR & Grant LW 2014. The efficacy of training cooperating teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39:77-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.12.007 [ Links ]

Hastings W 2010. Expectations of a pre-service teacher: Implications of encountering the unexpected. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3):207-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.493299 [ Links ]

Heeralal PJ & Bayaga A 2011. Pre-service teachers' experiences of teaching practice: Case of South African university. Journal of Social Sciences, 28(2):99-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2011.11892933 [ Links ]

Hobson AJ, Ashby P, Malderez A & Tomlinson PD 2009. Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don't. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1):207-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001 [ Links ]

Jeriphanos M 2017. Experiences and beliefs of mentors towards student teachers on teaching practice in Masvingo, Zimbabwe. Dynamic Research Journals-Journal of Economics and Finance, 2(4):1-8. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jeriphanos-Makaye/publication/337186004_Experiences_and_Beliefs_of_Mentors_Towards_Student_Teachers_on_Teaching_Practice_in_Masvingo_Zimbabwe/links/5dca7fbf299bf1a47b3044cf/Experiences-and-Beliefs-of-Mentors-Towards-Student-Teachers-on-Teaching-Practice-in-Masvingo-Zimbabwe.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Karasu Avci E & Ibret BÜ 2016. Evaluation of teacher candidates' views regarding to Teaching Practice-II. Kastamonu Education Journal, 24(5):2519-2536. [ Links ]

Kasapoglu K 2015. A review of studies on school experience and practice teaching in Turkey. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 30(1):147-162. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Koray_Kasapoglu/publication/282069470_A_review_of_studies_on_school_experience_and_practice_teaching_in_Turkey/links/5fdf810845851553a0db3075/A-review-of-studies-on-school-experience-and-practice-teaching-in-Turkey.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Kilgour P, Northcote M & Herman W 2015. Pre-service teachers' reflections on critical incidents in their professional teaching experiences. In T Thomas, E Levin, P Dawson, K Fraser & R Hadgraft (eds). Research and development in higher education: Learning for life and work in a complex world (Vol. 38). Milperra, Australia: HERDSA. Available at http://herdsa.org.au/research-and-development-higher-education-vol-38. Accessed 10 April 2020. [ Links ]

Kohler Riessman C 2008. Narrative analysis. In LM Given (ed). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n275 [ Links ]

Kudu M, Özbek R & Bindak R 2006. Okul deneyimi-I uygulamasina iliçkin ögrenci algilari (Dicle Üniversitesi örnegi) [The students perceptions about practice of school experience-I (The Dicle University sample)]. Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 5(15):99-109. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/esosder/issue/6129/82207. Accessed 10 April 2020. [ Links ]

Kukari AJ 2004. Cultural and religious experiences: Do they define teaching and learning for pre-service teachers prior to teacher education? Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 32(2):95-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866042000234205 [ Links ]

Lees A & Kennedy AS 2017. Community-based collaboration for early childhood teacher education: Partner experiences and perspectives as co-teacher educators. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 38(1):52-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2016.1274692 [ Links ]

Linn V & Jacobs G 2015. Inquiry-based field experiences: Transforming early childhood teacher candidates' effectiveness. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 36(4):272-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2015.1100143 [ Links ]

Lipovec A & Antolin D 2014. Slovenian pre-service teachers' prototype biography. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(2):183-193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.836090 [ Links ]

Loughran J, Brown J & Doecke B 2001. Continuities and discontinuities: The transition from pre-service to first-year teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 7(1):7-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600125107 [ Links ]

Martin S 1996. Support and challenge: Conflicting or complementary aspects of mentoring novice teachers? Teachers and Teaching, 2(1):41-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060960020104 [ Links ]

Matoti SN & Odora RJ 2013. Student teachers' perceptions of their experiences of teaching practice. South African Journal of Higher Education, 27(1):126-143. https://doi.org/10.20853/27-1-235 [ Links ]

McCabe A 2008. Narrative inquiry (journal). In LM Given (ed). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n275 [ Links ]

Merrick L & Stokes P 2003. Mentor development & supervision: "A passionate joint enquiry". The International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching, 1(1). Available at https://www.emccglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/30-1.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Miles BM & Huberman AM 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Miller K 2017. "El pasado refleja el futuro": Pre-service teachers' memories of growing up bilingual. Bilingual Research Journal, 40(1):20-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2016.1276031 [ Links ]

Miller K & Shifflet R 2016. How memories of school inform preservice teachers' feared and desired selves as teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53:20-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.002 [ Links ]

Mokoena S 2017. Student teachers' experiences of teaching practice at open and distance learning institution in South Africa. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(2): 122-133. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.306564 [ Links ]

Mudzielwana NP & Maphosa C 2014. Assessing the helpfulness of school-based mentors in the nurturing of student teachers' professional growth on teaching practice. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7):402-110. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n7p402 [ Links ]

Mukeredzi TG 2013. Professional development through teacher roles: Conceptions of professionally unqualified teachers in rural South Africa and Zimbabwe. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 28(11):1-17. Available at http://sites.psu.edu/jrre/wp-content/uploads/sites/6347/2014/02/28-11.pdf. Accessed 8 December 2020. [ Links ]

Mukeredzi TG 2017. Mentoring in a cohort model of practicum: Mentors and preservice teachers' experiences in a rural South African school. SAGE Open, 7(2):1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017709863 [ Links ]

Mukeredzi TG, Mthiyane N & Bertram C 2015. Becoming professionally qualified: The school-based mentoring experiences of part-time PGCE students. South African Journal of Education, 35(2):Art. # 1057, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n2a1057 [ Links ]

Muylaert CJ, Sarubbi V, Jr, Gallo PR, Neto MLR & Reis AOA 2014. Entrevistas narrativas: Un recurso importante en la investigation cualitativa [Narrative interviews: An important resource in qualitative research]. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 48(Esp2):184-189. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420140000800027 [ Links ]

Nel B & Luneta K 2017. Mentoring as professional development intervention for mathematics teachers: A South African perspective. Pythagoras, 38(1):a343. https://doi.org/10.4102/pythagoras.v38i1.343 [ Links ]

Okan Z & Yildirim R 2004. Some reflections on learning from early school experience. International Journal of Educational Development, 24(6):603-616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2004.02.004 [ Links ]

Onwuegbuzie AJ & Leech NL 2007. A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality & Quantity, 41:105-121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1 [ Links ]

Özdas F 2018. Evaluation of pre-service teachers' perceptions for teaching practice course. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 13(2):87-103. https://doi.org/10.29329/epasr.2018.143.5 [ Links ]

Özmen H 2008. Student teachers' views on school experience-I and -II courses. Ondokuz Mayis University Journal of Faculty of Education, 25:2537. [ Links ]

Patton MQ 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Pellikka A, Lutovac S & Kaasila R 2018. The nature of the relation between pre-service teachers' views of an ideal teacher and their positive memories of biology and geography teachers. Nordina, 14(1):82-94. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.4368 [ Links ]

Pierce T & Peterson Miller S 1994. Using peer coaching in preservice practica. Teacher Education and Special Education, 17(4):215-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840649401700402 [ Links ]

Ramazan O & Yilmaz E 2017. Okul öncesi ögretmen adaylarinin okul deneyimi ve ögretmenlik uygulamalarina yönelik görüclerinin incelenmesi [Analyzing the views of pre-service preschool teachers related to school experience and teaching practices]. AbantÍzzetBaysal UniversitesiEgitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 17(1):3 32-349. https://doi.org/10T7240/aibuefd.2017.17.28551-304638 [ Links ]

Randall L & Maeda JK 2010. Pre-service elementary generalist teachers' past experiences in elementary physical education and influence of these experiences on current beliefs. Brock Education Journal, 19(2):20-35. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v19i2T34 [ Links ]

Ravhuhali F, Lavhelani PN, Mudzielwana NP, Mulovhedzi S & Nendauni L 2020. Expectations vs reality: Investigating teaching practice challenges of Foundation Phase student teachers in a comprehensive university. Gender & Behaviour, 18(1):15027-15044. [ Links ]

Retnawati H, Sulistyaningsih E & Yin LY 2018. Students' readiness to teaching practice experience: A review from the mathematics education students' view. Jurnal RisetPendidikan Matematika, 5(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.21831/jrpm.v5i1.18788 [ Links ]

Robinson M 1998. Teachers mentor student teachers: Opportunities and challenges in a South African context. South African Journal of Higher Education, 12(2):176-182. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/AJA10113487_587. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Rodrigues LDAD, De Pietri E, Sanchez HS & Kuchah K 2018. The role of experienced teachers in the development of pre-service language teachers' professional identity: Revisiting school memories and constructing future teacher selves. International Journal of Educational Research, 88:146-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijer.2018.02.002 [ Links ]

Schoeman S & Mabunda PL 2012. Teaching practice and the personal and socio-professional development of prospective teachers. South African Journal of Education, 32(3):240-254. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n3a581 [ Links ]

Schofield M 2019. Why have mentoring in universities? Reflections and justifications. In M Snowden & JP Halsall (eds). Mentorship, leadership, and research: Their place within the social science curriculum. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95447-9_2 [ Links ]

Sedibe M 2014. Exploring student teachers' perceptions on mentoring during school experience at high schools in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 4(3):197-201. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n3p197 [ Links ]

Sibanda D & Jawahar K 2012. Exploring the impact of mentoring in-service teachers enrolled in a Mathematics, Science and Technology Education programme. Alternation, 19(2):257-272. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Doras-Sibanda/publication/277310247_Exploring_the_Impact_of_mentoring_in-service_Teachers_Enrolled_in_a_Mathematics_Science_and_Technology_Education_Programme/links/556705d808aeccd77736efea/Exploring-the-Impact-of-mentoring-in-service-Teachers-Enrolled-in-a-Mathematics-Science-and-Technology-Education-Programme.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Trotman J & Kerr T 2001. Making the personal professional: Pre-service teacher education and personal histories. Teachers and Teaching, 7(2):157-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600120054955 [ Links ]

Trubowitz S & Robins MP 2003. The good teacher mentor: Setting the standard for support and success. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Vásquez C 2004. "Very carefully managed": Advice and suggestions in post-observation meetings. Linguistics and Education, 15(1-2):33-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/jlinged.2004.10.004 [ Links ]

Whitebook M & Bellm D 2014. Mentors as teachers, learners, and leaders. Exchange, July/August:14-18. Available at https://cscce.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/publications/FINAL-218-Whitebook-Bellm1.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023. [ Links ]

Yildirim A & Simsek H 2016. Qualitative research methods in the social sciences (10th ed). Ankara, Turkey: Seçkin Publishing. [ Links ]

Yildiz Atlan R, Ulutas Í & Demiriz S 2018. Okul öncesi ögretmenligi lisans programinda yer alan "Ögretmenlik Uygulamasi" dersine iliçkin görüclerin karsilastmlmasi [Comparison of opinions on the "Teaching Practice" in early childhood education undergraduate program]. Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi Egitim Fakiiltesi Dergisi, 38(3):869-886. https://doi.org/10.17152/gefad.378603 [ Links ]

Zachary LJ 2002. The role of teacher as mentor [Special issue]. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 2002(93):27-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.47 [ Links ]