Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n1a2208

ARTICLES

Humanising life orientation pedagogy through environmental education

Pieter Swarts

School of Psycho-social Education, Faculty of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. 13233068@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article I focus on an initiative to determine how a group of 7 purposefully recruited Grade 10 in-service life orientation teachers in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda district of the North West province conceptualise socio-environmental issues and aim to determine whether their teaching-learning practices are aligned with the expectations of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. A qualitative research design was used to generate data through semi-structured interviews. The data were analysed thematically. A critical finding was that a need exists to include a situated knowledge approach to real-life socio-environmental issues for the purpose of humanising life orientation for learners. With this article, I wish to contribute to a particular discourse with regard to real-life socio-environmental issues through humanising life orientation pedagogies through environmental education. The potential merits of such a transformative approach, which is grounded in a critical pedagogical paradigm, are discussed as well.

Keywords: CAPS; environmental education; Life Orientation; transformative education

Introduction

In South Africa, an analysis of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) shows that the Department of Basic Education (DBE) wishes to ensure that learners acquire and apply knowledge, values and skills in ways that are meaningful to their own lives (DBE, Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2011). This, however, cannot be deduced from the aim of life orientation (hereafter LO), namely preparing learners to actively participate in community initiatives (DBE, RSA, 2011). To prepare learners for such initiatives, CAPS (DBE, RSA, 2011) focuses on a more constructivist approach towards teaching-learning with specific reference to active learning, critical and creative thinking. These performance principles embody an acknowledgement that the old, dehumanising teaching-learning practices, which are aligned with rote learning, should be replaced. This vision towards teaching-learning also permeates the aims of LO. Phrases such as "to guide and prepare learners", "to expose learners" and to "provide learners with opportunities" as well as to "develop learners' knowledge, values and skills" (DBE, RSA, 2011:9) are central to life skills education. Furthermore, these aims must prevent LO, a predominately skills-based school subject, from becoming too theory-driven (DBE, RSA, 2011). Although it can be argued that the inclusion of socio-environmental issues in the LO curriculum would be a positive step towards transforming LO into a hands-on subject (DBE, RSA, 2011), past and recent South African research has indicated the existence of a mismatch between curriculum expectations and teachers' pedagogy (Diale, 2016; Matshoba & Rooth, 2014). Textbook-focused teaching-learning approaches seem to be one of the major obstacles in this regard (Brown, 2013; Diale, 2016; Swarts, 2016). This concern may hamper effective teaching-learning of lesson topics with a socio-environmental focus.

Against this background, with the research reflected in this article I aimed to clarify Grade 10 LO teachers' conceptualisation of socio-environmental issues and to determine whether their teaching-learning practices are aligned with curriculum expectations. To reach this aim, the remainder of this article is structured as follows. Firstly, the positioning of socio-environmental issues in the LO curriculum is outlined. The focus then shifts to the conceptual framework, followed by an outline of the empirical investigation, the research findings, discussion and, lastly, a conclusion.

Conceptual Framework

In this section I draw upon the conceptual framework of humanising education. Here, Freire's ideas of humanising education where "true education incarnates the permanent search of people together with others for their becoming fully human in the world in which they exist" (Freire, 2000:32), serves as a guideline. In humanising education, according to Reimer and Longmuir, (2021), learners are addressed as multi-dimensional human beings, agentic in their lives and world. Thus, humanising teachers move beyond the four walls of classrooms to the inclusion of pressing social and environmental issues which can have a detrimental influence on the well-being of learners in their living environment.

Since the key focus of LO is to equip learners for successful living in a rapidly changing society (DBE, RSA, 2011), teachers are central in the process of guiding and preparing learners to lessen their vulnerability in their living environments (Nel, 2017). Therefore, the inclusion of socio-environmental issues cannot be narrowly framed by LO teachers as mere curriculum topics to be covered because they are included in the curriculum. These issues are real and affect people's daily lives (Buthelezi, 2017; Le Grange, Reddy & Beets, 2011; Magano, 2013). It is this emphasis that requires LO teachers to equip learners with knowledge, values and skills that are meaningful to their own lives (DBE, RSA, 2011). With this in mind, Lotz-Sisitka, Cavella, Kibuka-Sebitosi, Le Roux, Shava, O'Donoghue, Wilmot, Chikunda, Schudel, Mathiba, Dughudza, Rosenberg, Le Roux, Robson, Malema, Taylor, Conde, Kahn, Raven, Ramsurup, Misser, Mokoena, Snow, Moate, Neluvhalani, Mandikonza & Vogel's (2012:18) reference to an "inside-out" approach becomes important. Integrating situated socio-environmental issues as a source of meaningful learning is supported by both Bernstein (2009) and Sauvé (1996). Bernstein's (2009:209) reference to "content openness" and "improve ways of knowing" further supports Nel and Payne-Van Staden's (2017) view that LO should move beyond textbook knowledge. This is an indication that LO teachers cannot only teach about socio-environmental issues from textbooks or pre-determined lesson programmes.

Considering that CAPS seeks to improve the relevance and quality of teaching-learning through active learning, critical and creative thinking (DBE, RSA, 2011), change becomes a key concept for effective implementation of the curriculum (Fullan, 2007; Van den Berg & Schulze, 2014). At a conceptual level, a paradigm shift from talk-and-chalk strategies to learner-participation is required. In fact, the inclusion of socio-environmental issues in the LO curriculum calls on teachers to be sensitive to the socio-contextual challenges faced by learners in their lived environments (Dreyer & Loubser, 2005; Msila, 2016; Theron, 2014). I thus agree with Botha and Du Preez (2017) that LO teachers should be able to open up alternative pathways for learners to think about their world. Therefore, if the LO classroom is to become a place of promise and possibilities, the curriculum itself must be viewed as an activity driven policy document. This would mean that LO teachers should move away from the idea that socio-environmental issues are only about content to be covered. Instead, the LO teacher must act as an agent of transformation who moves beyond the transfer of knowledge (November, 2015) towards encouraging responsible citizenship.

Against this background, I argue that socio-environmental issues in CAPS, which are informed by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (DBE, RSA, 2011), must be viewed from a social-critical perspective. This perspective, which is based on the ideals of empowerment and social justice (Schulze, 2005), suggests that learners should learn and understand the complexities of socio-environmental issues from various perspectives. Comparing and sharing ideas in a cooperative learning environment can, therefore, create possibilities to accommodate a critical orientation (Cooperstein & Kocevar-Weidinger, 2004; Donald, Lazarus & Lolwana, 2002; Grosser, 2017). In this context, both learners and teachers will experience the LO curriculum as an active force (Le Grange, 2014) where it is possible to connect the word (knowledge) to the world (values and skills) -particularly regarding socio-environmental issues. This idea resonates with what Lotz-Sisitka (2012/2013:30) refers to as "learning of connection"; a strategy which may avoid misconceptions regarding the interactions between the social (human beings) and the environmental as a social construct.

Methodology

Research Design

The study reported on here was a qualitative study with a phenomenological approach. Since understanding was the goal (Merriam, 2002), a qualitative case study design assists the researcher to gain a holistic understanding of the "insiders'" views on a specific phenomenon (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007:82; Collingridge & Grantt, 2008:393).

Data Generation

Research participants from schools within the Potchefstroom municipal district were purposely selected after the necessary steps were taken in terms of access and consent from relevant stakeholders. The purposive sample consisted of seven Grade 10 in-service LO teachers: three female and four male teachers from former Model C and so-called township schools with knowledge and experience of the subject (Curtis, Murphy & Shields, 2014; O'Leary, 2014). Four of the research participants were specifically trained in teaching LO. Although three of the research participants were not qualified LO teachers, they had participated in training workshops on the most recent CAPS (DBE, RSA, 2011) for LO presented in North West. The criteria for recruiting these research participants were as follows: they had to have knowledge of the teaching of LO and they had to be teaching LO in their schools for at least 3 years.

I chose in-depth, semi-structured interviews because I was interested in the research participants' perceptions and teaching-learning methodologies about a specific phenomenon. The intersection between in-depth, semi-structured, individual interviews provides "a window into the complexities and richness" of a chosen phenomenon (Liamputtong, 2011:182). To ensure discussion during the interviews, my aim was to recruit a few participants who could best shed light on the phenomenon under investigating (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010).

Two research questions were put to participants: 1) How do you interpret socio-environmental issues within LO? and 2) What teaching-learning strategies do you use to facilitate LO lesson topics with a socio-environmental focus to ignite responsible citizenship?

Data Analysis

The audio-recorded data were analysed through the framework for qualitative analysis as developed by Creswell (2014). To ensure internal validity, a transparency process, which relied on member checking (O'Toole & Beckett, 2013), was implemented.

The recorded interviews were transcribed and coded according to emerging themes which related to the two research questions:

• Theme 1 : Socio-environmental issues and the act of caring.

• Theme 2: Teacher-textbook-driven pedagogy.

• Theme 3: Inability to develop contextually relevant teaching-learning material.

• Theme 4: Disregard for learners' human capital on socio-environmental issues.

Findings

Although the participants illustrated a satisfactory view on what constituted socio-environmental issues in the LO curriculum, it was their reliance on textbooks that revealed similarities with past and present research findings which indicate that teachers struggled to implement LO capably (Beyers, 2013; Francis & Viljoen, 2014; Magano, 2011; Phasha & Mcgogo, 2012; Swarts, 2016; Theron & Dalzell, 2006). The findings, based on the comments of the participants regarding the two research questions, are discussed in more detail below.

Discussion of Data

Theme 1 : Environmental Issues and the Act of Caring

What emerged from the data was that all the participants perceived socio-environmental issues as acts that could be linked to either human beings or the natural environment.

Considering socio-environmental issues as a caring act towards human beings, one participant (a female teacher from a former Model C school) pointed out: "It links with Ubuntu and the Christian principle of caring for others."

Another participant (a female teacher from a former Model C school) explained: "In context to LO, it is to give the kids an awareness of how to live, how to be, how to take care of their world."

A valuable point was made by one participant (a male teacher from a township school):

It focuses on the well-being of the person. I think it integrates well with well-being of a human beings ' health and fitness. In terms of those two aspects, social and environmental responsibility links very well with the human as a whole. The above sentiment was echoed by another participant (a male teacher from a township school): "I think this is an important facet to develop the learner in his or her totality. I don't think this must ever be removed from LO. They [learners] must be orientated in terms of their responsibility. This is important."

One participant (a male teacher from a former Model C school) indicated that learners should be prepared for the real world and the challenges thereof: "It does not help us much when the learner goes into the world and he or she doesn't have an idea of the crises in this world, and especially in South Africa."

From the above responses, socio-environmental issues are seen as an act of human caring. However, Ubuntu, a learner-centred approach (Beets & Le Grange, 2005; Racheal & Magano, 2016) that can make a valuable contribution towards developing the necessary knowledge, values and skills to act in a socially responsible way towards others, cannot be divorced from the environment. Human beings are part of their environment (Hallows & Butler, 2002), therefore, the caring principle of Ubuntu should be regarded as an act that also incorporates the individual's environment. For this reason, Bezuidenhout (2008:7) is of the view that the "external environment should, however, not be considered as divorced from individual-human [sic] factors, as a complex interaction exists between people and the environment they live in."

Surprisingly, one participant (a male teacher from a former Model C school) seemed to interpret socio-environmental issues as an act purely geared towards the natural environment:

I think this topic refers to our responsibility that we as human beings have towards the environment. Here I can refer to air pollution. It is us [sic] that causes air pollution. It is the responsibility of the human being towards his environment in terms of air pollution.

Participants' reductionist views result in them missing out on the depth of this topic and how it is intertwined with both human and environmental issues in the socially constructed environment (Reddy, 2011).

Theme 2: Teacher-textbook-driven Pedagogy Most of the participants (six of seven) revealed that they were not adequately equipped to use alternative sources to successfully address socio-environmental issues. There was a noticeable reliance on textbooks, as expressed by the participants:

I first look at the policy document and then I take the textbook and concentrate on what they [learners] must learn for the examination (male participant from a former Model C school).

No, I work according to the guidelines as set out in the policy document and then go back to my textbook and then do my preparation (male participant from a former Model C school).

I basically look at the textbook (male participant from a township school).

I first use the textbook that I'm using at school (male participant from a township school).

What I do is to go to the textbook and see what it is, the contexts thereof. Then I try to apply it to the learners' life (female teacher from a township school).

What I do is to look at my textbook and what it really is (female participant from a former Model C school).

The downside of a text-book-driven approach is that learners are not regarded as whole human beings in their lived environment, and, therefore, represents a disconnect with holistic education as emphasised in LO. Textbook activities are centred on the teachers' conceptions of what constitutes an ideal teaching-learning situation for socio-environmental issues. It can, therefore, be argued that these participants view their learners as seekers of compartmentalised socio-environmental knowledge. Furthermore, "learning to be" (Mahmoudi, Jafari, Nasrabadi & Liaghatbar, 2012:182), which can be interpreted as learning to be human through the acquisition and application of knowledge, values and skills conducive to self-development and articulation of voice (DBE, RSA, 2011), is being neglected through a textbook approach. This is a justifiable concern because textbooks confine life skills education about socio-environmental issues to an indoor activity. It is, therefore, possible that learners are likely to miss out on the complexities and effects of socio-environmental issues in their lived environment. Here I refer specifically education on sexuality and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Few would disagree that a textbook-driven approach with compartmentalised bits of knowledge of sensitive learning topics may have little impact on preventative messages. The limited capacity of textbooks, as pointed out by Geen (2007:11), is that "information is put into the pupil; the teacher does not draw ideas from the pupil." One might argue that a textbook-driven approach towards socio-environmental issues poses a serious threat to learner participation. Griessel-Roux, Ebersöhn, Smit and Eloff (2005) are of the opinion that if preventative messages, especially on socio-environmental issues such as HIV and AIDS are taught to and learnt by learners, the assumption that they would be able to apply such knowledge to risky situations is questionable. The reason for this is that young people being bombarded with HIV and AIDS knowledge and statistics often leads to "AIDS fatigue" (De Lange, 2014:381) or it may even have a "demoralising" (McNiff, 2008:71) effect. Learners should, therefore, not be regarded merely as passive consumers of textbook knowledge about socio-environmental issues. In fact, LO teachers have a special responsibility to focus on learners' expressive potential and participation in real-life socio-environmental issues that affect their lives.

Theme 3: Unable to Develop Contextually Relevant Teaching-learning Material

From the interviews it became clear that participants struggled to incorporate real-life examples of socio-environmental issues to their teaching-learning pedagogy. This is confirmed by the following teacher statements:

There are a lot of examples from the book which I relate to the physical environment (female participant from a former Model C school).

What I need [on socio-environmental issues] is in the textbook (female participant from a former Model C school).

Teachers who act according to the above statements have the potential to alienate learners from the learning experience, especially when they approach socio-environmental issues from a behaviouristic perspective. Such an approach may instil in learners a dependency habit (Makoelle, 2016) because conceptions around socio-environmental issues are determined by the teacher.

Theme 4: Disregard for Learners' Human Capital on Socio-environmental Issues

Although most of the participants viewed socio-environmental issues from a caring perspective, they did not demonstrate any initiative to identify topical issues in the lived environment that could have been used to involve learners in a democratic and proactive manner. A fundamental concern, therefore, is that the research participants applied a content-driven teaching-learning approach towards socio-environmental issues. This rigid approach towards socio-environmental issues does not add value to meaningful learning. Plevin (2016) asserts that meaningful learning must be linked to learners' lived environment and their interest, and I argue that LO teachers must live up to this responsibility.

The need for an alternative pathway to address socio-environmental issues

There is a growing awareness that schools need to be places that not only impart knowledge about environmental issues (Boxely, Krishnamurthy & Ridgway, 2016). Makoelle (2016), for example, emphasises that teachers should acknowledge the cultural capital of learners when planning their teaching. Through such an act it will be possible for learners not only to relate to socio-environmental issues through linking their inner and outer world experiences but also to make this topic relevant to their lived environment. For this reason, the inclusion of socio-environmental issues in the LO curriculum is a positive step because it provides opportunities for debate on the interaction thereof in real life. LO, as a compulsory school subject, is perfectly positioned to assist learners to become responsible citizens in their environment, to solve problems, to make informed decisions and choices and to take appropriate action to live meaningfully and successfully in a rapidly changing society (DBE, RSA, 2011). This reinforces the need for a new kind of LO teacher - one who is able to humanise local socio-environmental issues for learners. As LO is about developing the individual holistically (DBE, RSA, 2011) - not just his or her knowledge - it is argued that environmental education can fulfil this need. Following Orr's (2004) notion that all education is environmental education, it seems possible that such an approach can be infused with LO to facilitate the blending of local knowledge, values and skills of real-life socio-environmental issues to enable "responsible citizenship" (DBE, RSA, 2011:8), as highlighted in education policy statements.

The question now is: What is environmental education (hereafter EE)? My concern in this regard is more specifically with opportunities that the LO curriculum provides for addressing socio-environmental issues through EE. In this regard, Orr's (2004:9), explanation that EE is "good education" because "it's all about empowering the individual with knowledge, values, attitudes and skills on environmental issues" is useful. It is also worth mentioning that Swarts (2016) as well as Swarts, Rens and De Sousa (2015) indicate that multiple parallels exist between EE and LO. Prominent among these are the world operating as a set of related systems, a holistic approach towards education, learner-centeredness, dialogue, encouraging socially and environmentally responsible citizenship and the focus on local environmental issues. I, therefore, argue that infusing EE with LO serves as an alternative to separate real-life socio-environmental issues and the complexities thereof in the lived environment from textbook pages.

New spaces for engagement: Bridging the knowledge, values, and skills gap through infusing EE with LO

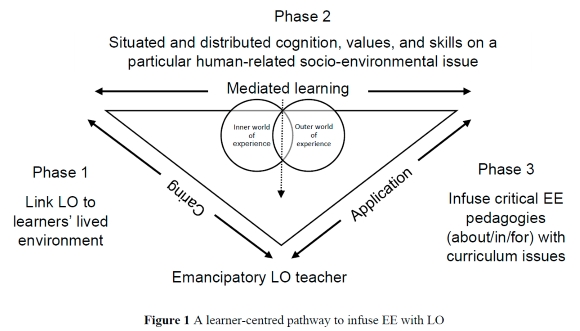

The suggested framework, depicted in Figure 1, follows a participatory pathway, and allows space for more inclusive socio-environmental content that can serve as a catalyst for unsustainable practices. The unquestioned assumption is that this schematic illustration may serve as a practical guide for LO teachers on how to move beyond a reductionist approach to a more engaged pedagogy regarding socio-environmental issues. Hence, I advocate that socio-environmental issues should be approached from what I refer to as a caring-supporting perspective, which encapsulates three phases. Phase 1 should focus on linking socio-environmental issues with learners' lived environments. Phase 2, which flows from Phase 1, should focus on contextualising and the embodiment of knowledge, values, and skills. Phase 3, which flows from Phases 1 and 2, should focus on the application of knowledge, values, and skills in the lived environment. This suggested framework serves the following purpose: it provides a practical way to encourage teachers to work removed from LO textbooks and to design suitable socio-environmental learner activities that are sensitive to their lived environment with the fundamental goal of enhancing the learning pillar "learning to be."

While it is impossible to separate the individual components (cf. Figure 1), I discuss each separately, starting with the learner.

The engaged learner

It is important to note that teachers should use the learner's whole being (i.e., body, mind, and soul) as an instrument of learning. I suggest that such an approach towards the learner (putting the "self' in learning) connects with holistic development (DBE, RSA, 2011:8). This curriculum aim alludes to what Le Grange (2004:387) refers to as "embodiment." The assumption, according to him, is that if the mind is triggered with sufficient information, "mind knowledge" will lead to "right bodily actions." Therefore, and according to Chen and Martin (2015), the need to interact with one's environment is essential because the context demands action and reflection. It appears that learning about socio-environmental issues should then be a transformative experience for learners, which is indeed the goal of LO (DBE, RSA, 2011). The logic of making learning a transformative experience for learners is that processes such as gaining critical insight and having encounters with socio-environmental issues may develop into what Ford (2016:212) calls "a process of collective discovery of unsustainable practices." In this way, life skills education on socio-environmental issues becomes an emancipatory act, which resonates with what Freire (2000:48) refers to as the "notion to develop a critical awareness of one's social reality." For this reason, knowledge of the lived environment should inspire learners to form new perspectives and take positive actions on how to live sustainably in their environment.

The emancipatory LO teacher

According to this framework, the teacher does not merely "deliver" the LO curriculum to the learners' minds (see, for example, Jansen, 2017:169). Instead, the teacher's expertise is in his/her knowledge to empower learners (Horton & Freire, 1990) where they construct meaning in a rich learning environment. This, I believe, is possible through a caring approach. For example, rather than just teacher talk about topical socio-environmental issues, he/she locates lesson topics in the learners' lived environment to evoke participation. In this instance, the LO teacher becomes what Kesson (2016) calls a thoughtful bridge builder between the content and the learner in his or her totality.

Mediated learning content

As has been mentioned earlier, learners enjoy having discussions about real-life issues that affect them. Accordingly, LO lesson topics should not only become a socially organised activity, but a holistic and transformative experience situated in participatory contact zones among learners and between learners and the LO teacher. I, therefore, argue for the need to link the LO classroom with the learners' lived world. EE serves this purpose as it focusses on the real world (Winograd, 2016). In this regard hooks (1994) and Noddings (2016) remind us that the environment invites learners to become engaged in and informed about issues that affect their lives.

Situated (local) learning through real-life case-study instruction can sustain meaningful encounters about, in and for lived experiences with real-life socio-environmental issues. Such approaches, which are central to EE (Le Grange, 2004), emphasise for me, as an LO practitioner, awareness of, presence in, and being with the environment. Moreover, these three approaches to socio-environmental issues in the lived environment mean that the LO teacher can guide learners to be able to construct their own knowledge and can be in charge of their learning through the articulation of their voices. For instance, the interplay between HIV, the economic environment, the social environment, and the bio-physical environment can be addressed from an environmental point of view that acknowledges the indigenous cultural capital of learners. Case studies on the phenomenon of sugar daddies or blessers can be used to raise critical consciousness (Freire, 2000) among learners on interconnected issues such as self-awareness, self-esteem, making good decisions, power, power relations, masculinity, femininity and gender, stereotypical views of gender roles and responsibilities, sexual abuse, teenage pregnancy, and violence (DBE, RSA, 2011). Using a dialogical approach towards such issues through contemporary real-life case studies can engage learners as human beings in their own learning (Le Grange, 2004). Freire (2000:75-76) states, for example, that dialogue "is the encounter between men, mediated by the world in order to name and change the world." Such learning, according to Grosser (2016), should include traits such as humility, empathy, integrity, perseverance, open-mindedness, and fair-mindedness. It would, therefore, be reasonable to claim that Bloom's taxonomy should be used to design inquiry-based questions to attach a human dimension to HIV. In this way, not only learners' cognitive domain but also their affective domain, which targets values, attitudes, emotions, interest, and feelings (Booyse & Du Plessis, 2014; Mlaba, 2015) to enhance sustainable change, can simultaneously be assessed.

Assessment to support dialogical learning on socio-environmental issues should also be moved from assessment of learning (summative) to assessment for learning. According to Lombard (2016) and Lombard and Nel (2017), assessment for learning promotes functional learning, that is, engagement with the learning material. This type of assessment can then be used to sow the seeds of "responsible citizenship" in learners, as emphasised in education policies (DBE, RSA, 2011:8). For example, a school campaign to stop sexual abuse will be a worthy cause to raise learners' awareness of HIV and AIDS education. Here learners can reconcile their newly acquired knowledge and skills to create new possibilities, an action that relates to Freire's (2000:34) notion of connecting "the word to the world." Such an approach, which resonates with what Lotz-Sisitka (2012/2013:30) calls "learning of connection", justifies the infusion of LO with EE on socio-environmental issues.

Limitations of the Study

The small sample size, only seven participants from seven different schools in the Potchefstroom municipal district, limits the generalisability of the research findings. Nevertheless, the findings provide sufficient data to suggest a learner-centred pathway to infuse EE with LO, with the potential to be refined and modified to suit contextual needs that will best benefit diverse learners as the curriculum intends LO to do. Furthermore, this small-scale study opens up the possibility for future research because LO teachers have a critical role to play in the rethinking of social and environmental responsibility in light of real-life issues, such as climate change, the recent Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, teenage pregnancy, bullying incidents and so forth, through critical thinking, agency and concrete action.

Conclusion

The introduction of a practical framework, as proposed, serves as a useful guide of what is possible to ignite a productive approach towards real-life socio-environmental issues. This framework also holds potential to contribute to the (re)awakening of a holistic development of responsible citizens, as described in education policies.

Notes

i. The author declares no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Beets P & Le Grange L 2005. 'Africanising' assessment practices: Does the notion of hold any promises [Special issue]. South African Journal of Higher Education, 19:1197-1207. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/EJC37215. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Bernstein B 2009. On the curriculum. In U Hoadley & J Jansen (eds). Curriculum: Organizing knowledge for the classroom (2nd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Beyers C 2013. Sexuality educators: Taking a stand by participating in research [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 33(4):Art. #813, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412171342 [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout C 2008. Introduction and terminology dilemma. In C Bezuidenhout & S Joubert (eds). Child and youth misbehaviour in South Africa: A holistic approach (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Bogdan RC & Biklen SK 2007. Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (5th ed). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Booyse C & Du Plessis E 2014. Curriculum studies: Development, interpretation, plan and practice (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Botha J & Du Preez P 2017. An introduction to the history and nature of human rights and democracy in the South African curriculum. In M Nel (ed). Life Orientation for South African teachers (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Boxely S, Krishnamurthy G & Ridgway MA 2016. Learning care for the earth with Krishnamurti. In K Winograd (ed). Education in times of environmental crises: Teaching children to be agents of change. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brown J 2013. Attitudes and experiences of teachers and students towards Life Orientation: A case study of a state-funded school in Eldorado Park, South Johannesburg. MA(DS) dissertation. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/171729bc-02c6-4514-91d1-fa4f6b0dfb14/content. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Buthelezi T 2017. Making sense of sociology in schooling today. In L Ramrathan, L le Grange & P Higgs (eds). Education studies for initial teacher development. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Chen JC & Martin AR 2015. Role-play simulations as a transformative methodology in environmental education. Journal of Transformative Education, 13(1):85-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614560196 [ Links ]

Collingridge DS & Gantt EE 2008. The quality of qualitative research. American Journal of Medical Quality, 23(5):389-395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860608320646 [ Links ]

Cooperstein SE & Kocevar-Weidinger E 2004. Beyond active learning: A constructivist approach. Reference Services Review, 32(2):141-148. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320410537658 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Curtis W, Murphy M & Shields S 2014. Research and education: Foundations of education studies. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

De Lange N 2014. The HIV and AIDS academic curriculum in higher education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(2):368-385. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/EJC153551. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement Grades 10-12: Life Orientation. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/ CAPS%20Commnets/FET/LIFE%20ORIENTATION%20GRADES%2010%20-%2012%20EDITED.PDF?ver=2018-08-29-154752-423. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Diale BM 2016. Life Orientation teachers' career development needs in Gauteng: Are we missing the boat? South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(3):85-110. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-3-670 [ Links ]

Donald D, Lazarus S & Lolwana P 2002. Educational psychology in social context (2nd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dreyer J & Loubser C 2005. Curriculum development, teaching and learning for the environment. In CP Loubser (ed). Environmental education: Some South African perspectives. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Ford DR 2016. The beautiful risk of education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(2):210-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.871405 [ Links ]

Francis D & Viljoen M 2014. Learners' perceptions and experience of the content and teaching of sexuality education: Implications for teacher education. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(3):707-716. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/EJC159157. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Freire P 2000. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2007. The new meaning of educational change (4th ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Geen AG 2007. Effective teaching for the 21st century: Priorities in secondary education (4th ed). Cardiff, Wales: UWIC Press. [ Links ]

Griessel-Roux E, Ebersöhn L, Smit B & Eloff I 2005. HIV/AIDS programmes: What do learners want? South African Journal of Education, 25(4):253-257. [ Links ]

Grosser M 2016. Development of the critical thinker. In ER du Toit, LP Louw & L Jacobs (eds). Help, I'm a student teacher!: Skills development for teaching practice (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Grosser M 2017. Cooperative learning in the Life Orientation classroom. In M Nel (ed). Life Orientation for South African teachers (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Hallows D & Butler M 2002. Power, poverty, and marginalized environments: A conceptual framework. In DA McDonald (ed). Environmental justice in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

hooks b 1994. Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Horton M & Freire P 1990. We make the road by walking: Conversations on education and social change. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Jansen J 2017. As by fire: The end of the South African university. Cape Town, South Africa: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Kesson K 2016. Cultivating curriculum wisdom: Meeting the professional development challenges of the environmental crisis. In K Winograd (ed). Education in times of environmental crises: Teaching children to be agents of change. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2010. Practical research: Planning and design (9th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Le Grange L 2004. Embodiment, social praxis and environmental education: Some thoughts. Environmental Education Research, 10(3):387-399. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462042000258206 [ Links ]

Le Grange L 2014. Currere's active force and the Africanisation of the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(4): 1283-1294. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/epdf/10.10520/EJC159186. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Le Grange L, Reddy C & Beets PAD 2011. Socially critical education for a sustainable Stellenbosch 2030. In M Swilling & B Sebitosi (eds). Sustainable Stellenbosch by 2030. Stellenbosch, South Africa: SUN Media. [ Links ]

Liamputtong P 2011. Focus group methodology: Principles and practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Lombard K 2016. Classroom assessment. In ER du Toit, LP Louw & L Jacobs (eds). Help, I'm a student teacher!: Skills development for teaching practice (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Lombard K & Nel M 2017. Assessment in Life Orientation. In M Nel (ed). Life Orientation for South African teachers (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka H 2012/2013. Think piece: Conceptions of quality and 'learning as connection' - Teaching for relevance. Southern African Journal of Environmental Education, 29:25-38. Available at https://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajee/article/view/122256. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka H, Cavella W, Kibuka-Sebitosi E, Le Roux C, Shava S, O'Donoghue R, Wilmot D, Chikunda C, Schudel I, Mathiba T, Dughudza P, Rosenberg F, Le Roux R, Robson L, Malema V, Taylor J, Conde L, Kahn A, Raven G, Ramsurup P, Misser S, Mokoena S, Snow J, Moate M, Neluvhalani E, Mandikonza C & Vogel C 2012, February. National case study. Teacher professional development with an education for sustainable development focus in South Africa: Development of a network, curriculum framework and resources for teacher education (Working Document 1.3.09). Tunisia: Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA). Available at https://triennale.adeanet.org/2012/sites/default/files/2018-07/1.3.09_document_sub_theme_1.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Magano MD 2011. The new kind of a teacher to handle the new subject-Life Orientation, in a township high school in South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 28(2):119-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2011.11892936 [ Links ]

Magano MD 2013. The emotional experiences of HIV/AIDS affected learners who stay with caregivers: A wellness perspective. Journal of Educational Studies, 12(2):19-34. [ Links ]

Mahmoudi S, Jafari E, Nasrabadi HA & Liaghatdar MJ 2012. Holistic education: An approach for 21 century. International Education Studies, 5(2):178-186. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n3p178 [ Links ]

Makoelle TM 2016. Developing an inclusive strategy for inclusive teaching and learning in a diverse classroom. In MP van der Merwe (ed). Inclusive teaching in South Africa. Stellenbosch, South Africa: SUN Press. https://doi.org/10.188/9781928355038 [ Links ]

Matshoba H & Rooth E 2014. Living up to expectations?: A comparative investigation of Life Orientation in the National Senior Certificate and National Certificate (Vocational). Pretoria, South Africa: UMALUSI. Available at https://www.umalusi.org.za/docs/assurance/2014/lifeorientation.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

McNiff J 2008. Taking action to combat HIV and Aids. In L Wood (ed). Dealing with HIV and AIDS in the classroom. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2002. Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mlaba SM 2015. Grade ten teachers ' implementation of the South African curriculum. Saarbrücken, Germany: Lap Lambert Academic Publishing. [ Links ]

Msila V 2016. Revival of the university: Rethinking teacher education in Africa. In V Msila & MT Gumbo (eds). Africanising the curriculum. Indigenous perspectives and theories. Stellenbosch, South Africa: SUN PReSS. [ Links ]

Nel M 2017. Introduction. In M Nel (ed). Life Orientation for South African teachers (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Nel M & Payne-van Staden I 2017. Life skills. In M Nel (ed). Life Orientation for South African teachers (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Noddings N 2016. Loving and protecting earth, our home. In K Winograd (ed). Education in times of environmental crises: Teaching children to be agents of change. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

November I 2015. The teacher as an agent of transformation. In S Gravett, JJ de Beer & E du Plessis (eds). Becoming a teacher (2nd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson. [ Links ]

O'Leary Z 2014. The essential guide to doing your research project (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Orr DW 2004. Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press. [ Links ]

O'Toole J & Beckett D 2013. Educational research: Creative thinking and doing (2nd ed). South Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Phasha N & Mcgogo JB 2012. Sex education in rural schools of Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 31(3):319-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2012.11893041 [ Links ]

Plevin R 2016. Take control of the noisy class: From chaos to calm in 15 seconds. Glasgow, Scotland: Crown House Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Racheal M & Magano MD 2016. The ubuntu principle amongst the Shona speaking people in promoting the wellness of HIV and AIDS orphaned learners in Zimbabwe. Indilinga: African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 15(1):28-17. [ Links ]

Reddy C 2011. Inaugural address. Environmental education and teacher development: Engaging a dual curriculum challenge. Southern African Journal of Environmental Education, 28:9-29. Available at https://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajee/article/view/122241. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Reimer K & Longmuir F 2021. Humanising students as a micro-resistance practice in Australian alternative education settings. In JK Corkett, CL Cho & A Steele (eds). Global perspectives on microaggressions in schools: Understanding and combatting covert violence. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sauvé L 1996. Environmental education and sustainable development: A further appraisal. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 1:7-34. Available at https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/490. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Schulze S 2005. Paradigms, ethics and religion in environmental education. In CP Loubser (ed). Environmental education: Some South African perspectives. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Swarts P, Rens J & De Sousa L 2015. Viewpoint: Working with environmental education pedagogies in Life Orientation to enhance social and environmental responsibility. Southern African Journal of Environmental Education, 31:98-109. Available at https://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajee/article/view/137676. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Swarts PA 2016. Die fasilitering van sosiale en omgewingsverantwoordelikheid binne Lewensoriëntering deur omgewingsopvoeding. PhD tesis. Potchefstroom, Suid-Afrika: Noordwes-Universiteit. Beskikbaar te https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/21231?show=full. Geraadpleeg 28 Februarie 2023. [ Links ]

Theron L 2014. Being a 'turnaround teacher': Teacher-learner partnerships towards resilience. In M Nel (ed). Life orientation for South African teachers. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Theron L & Dalzell C 2006. The specific Life Orientation needs of Grade 9 learners in the Vaal Triangle region. South African Journal of Education, 26(3):397-412. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/93/44. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Van den Berg G & Schulze S 2014. Teachers' sense of self amid adaption to educational reform. Africa Education Review, 11(1):59-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2013.853567 [ Links ]

Winograd K 2016. Teaching in times on environmental crises: What on earth are elementary teachers to do? In K Winograd (ed). Education in times of environmental crises: Teaching children to be agents of change. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Received: 17 May 2021

Revised: 11 April 2022

Accepted: 16 August 2022

Published: 28 February 2023