Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n1a2023

ARTICLES

Partnership to promote school governance and academic experience: Integration of remote learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in the uMkhanyakude district

B.A. NtuliI; D.W. MncubeI; G.M. MkhasibeII

IDepartment of Social Science Education, Faculty of Education, University of Zululand, Kwa-Dlangezwa, South Africa. mncubedm@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Professional Practice, Faculty of Education, University of Zululand, Kwa-Dlangezwa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Despite high hopes that schools are institutions of integrity and are properly governed, very few have demonstrated this with distinction. With this article we argue that good governance depends on the partnership between schools and parents in times of emergency. The theoretical framework from Epstein's theory of overlapping spheres of influence was used to alarm stakeholders to guard against overlapping one's roles during an emergency. In the study reported on here we used a qualitative research method, which allows data to be collected using semi-structured interviews and focus-group discussions as research instruments. The data were collected from stakeholders of school governing bodies (SGBs) and school management teams (SMTs) through WhatsApp and Zoom meetings. Thematic analysis was used to analyse qualitative data. The research findings reveal, among other problems, that most parents are digital immigrants who refuse to participate in virtual platforms for fear of endorsing remote learning, and that poor teaching and learning is due to a lack of access to digital technology, data, and poor connectivity. We recommend that parents should support remote learning for learners to achieve quality education beyond the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

Keywords: governors; parental involvement; performance; remote learning; stakeholders

Introduction and Background

Before 1994, the South African education system marginalised the voice of Black parents in school governance (Duma, 2014; Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018). After the dawn of the democratic dispensation, the South African Schools Act of 1996 (SASA) (Republic of South Africa [RSA], 1996a) was introduced firstly to advance literacy and innovation, and secondly to close the gap that existed between parents and schools by promoting partnership in education. Nhlabati (2015) and Youngs (2017) long supported the involvement of parents during emergency periods in decision-making to achieve academic efficacy. However, various challenges hinder collaborative partnerships in schools that are needed to promote the introduction of electronic learning (e-learning) platforms to fast-track innovation, virtual teaching, and learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, most schools continued a dysfunctional trend (Dube, 2020; Mpungose, 2020), even though the legislation dictated the need for a change in parents' behaviour towards embracing remote learning to improve school governance. Parents as stakeholders offer a variety of benefits for a school ranging from school governance to academic support by formulating school policies that favour the integration of cutting-edge technology in the 21st century (Duku & Salami, 2017). Schools in rural areas (herein referred to as schools in deprived contexts) have the responsibility to embrace remote learning, or else they will be left out of mainstream education during emergencies. School governance headed by digital immigrants tends to ignore e-learning platforms and take remote learning lightly (Duku & Salami, 2017).

Mncube, Davies and Naidoo (2014) and Van der Westhuizen, Basson, Barnard, Bondesio, De Witt, Niemann, Prinsloo and Van Rooyen (2002) argue that the positive effect of parental involvement in school governance and learners' academic experience is hard to witness when parents are still ignorant about the purpose of remote learning in their institutions. This is evident because some parents take remote learning lightly, without enforcing home-school partnerships (Okeke, 2014). In essence, Alhassan (2016), Basson and Mestry (2019) and Mncube et al. (2014) hold that the current model of school governance is static and does not promote the use of new technology to strengthen the partnership between schools and parents. Basson and Mestry (2019) note that strong policy imperatives that embrace online platforms can convert national initiatives to sound local policy initiatives that directly impact schools. The work done by the Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau advocates for paradigm shifts that recognise the need for parental involvement championing the integration of online learning platforms as a new form of teaching and learning in rural schools (Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018).

Section 29 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, (hereafter referred to as the Constitution) asserts that every person has the right to basic and adult basic education (RSA, 1996b). This affirmation underscores a strongly held belief that education (delivered either online or through face-to-face platforms) is one of the pillars of economic development and social transformation in a country (Mncube et al., 2014). This undertaking is even more relevant in a country where the imbalances and injustices in an area like education are well documented (Bayat, Louw & Rena, 2014). Most learners in deprived contexts lack basic modern technologies such as hardware resources (computers, laptops, mobile phones, and others) and software resources (software applications, social media, and others). These technologies demand change in the teaching of literacy and numeracy as reported in the study conducted by the World Economic Forum in 2013 (Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018; Ntseto, 2015). This failure to integrate remote learning continues to cripple the education of the most vulnerable learners in crucial subjects like mathematics and science (Bayat et al., 2014). The SGBs were singled out in the Constitution to play a governance and an oversight role, and, in turn, mitigate learners' academic challenges by promoting the use of modern technologies by teachers to support multimodal teaching strategies. However, most SGB members are digital immigrants because they lack the technical skills to perform their mandate as envisaged in the Constitution (Mkhasibe & Mncube, 2020). In under-resourced schools, these digital immigrants cannot discharge their duties to the best of their ability (Basson & Mestry, 2019; Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018).

Parents as Partners to Schools in Promoting Remote Learning

Parental involvement during an emergency period is essential to the work of the SMT as the partnership leads to improved integration of e-learning despite socio-economic challenges (Ndebele, 2015). However, differences in education level, language, and cultural styles between parents and school staff sometimes create unnecessary tension and make it more challenging to promote remote learning (Mestry, 2020). It is common knowledge that parents with no formal education participate less than their counterparts in promoting during school governance (Mpungose, 2020). Parental involvement in school activities in urban areas happens virtually through Zoom and WhatsApp platforms, and they volunteer to purchase both hardware resources and software applications for their children (Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018).

To turn the situation around, the government encourages a new sense of urgency for parents from deprived contexts to actively participate in online platforms (Dube, 2020). Mpungose (2020) cautions against unilateral decision-making in introducing remote learning platforms by schools without the involvement of parents, as this might weaken learner participation. The resolve shown by SASA to entrust parents with the authority of governing schools is arguably the most important responsibility given to the SGB to consider persuading parents to embrace e-learning when formulating school policies (RSA, 1996a). In contrast, digital immigrant parents in deprived contexts too often play the role of passive participants, owing to their limited knowledge and literacy (Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018; Ndebele, 2015). Mestry (2014) views education as a multifaceted dimension with strong discourse dependent on several factors, such as curriculum management, socio-economic condition, and demographic and geographical phenomena outside the classroom. This sentiment is shared in a study by Ndebele (2015), who explains that learners' academic experience is multidisciplinary, and its success during emergencies extends beyond the confines of the classroom. The role of parental involvement remains to support schools migrating to online learning platforms by encouraging parents to lead the home-school remote learning initiative (Khoza, 2020). The policy acknowledges that institutions like schools cannot succeed when isolated from the community. All measures and interventions to infuse remote learning must be taken in the best interest of the school (Mncube et al., 2014; Xaba, 2011).

SGBs in Promoting Remote Learning as Part of School Governance

SGBs supports the Constitution of the country as they seek to promote the best interest of schools (RSA, 1996a). SGBs are entrusted with a weighty responsibility in this respect, providing an institutional framework for overseeing the implementation of SGB resolutions. In instances where SGBs are well-capacitated, sound decisions are likely to benefit remote learning initiatives to run concurrently with face-to-face learning to improve the quality of learners' academic experience (Mestry, 2014). Mkhasibe and Mncube (2020) argue that when schools invest in modern technologies (hardware and software) with the support of parents, the potential benefits for learners are great. When school-related, family-related, or community-related barriers deter the integration of e-learning during an emergency, learners lose an important source of support for their academic experience. Mpungose (2020) identifies five major kinds of barriers to online learning: (i) poor connectivity, (ii) a lack of access to advanced digital devices such as smartphones, tablets and desktops, (iii) a lack of educational software, (iv) a lack of decisive policy imperatives, (v) a lack of continuing professional teacher development. In South Africa, a new emerging trend is seen where digital immigrant parents resist and demonise online learning as a bad teaching strategy likely to lead to learners' poor academic experience (Duma, 2014). However, SGBs, without proper information and the skills to integrate online learning, are a threat to the school, teachers, and learners (Mncube et al., 2014).

International Trends in Promoting Remote Learning Platforms

Poisson (2014) documented that parental involvement in school governance is mandatory to promote innovations like e-learning platforms to schools and the broader society. The evidence for this can be seen in countries such as the United States of America (USA), and South American and Asian countries. The departments of education in these countries understand what it means to promote e-learning or remote learning platforms as a means to decentralise the education system while promoting active parental involvement (Myende, 2019). The USA encourages citizen participation in school governance through virtual platforms so that parents would be held accountable for their practice during emergencies (Duma, 2014; Mohapi & Netshitangani, 2018).

In South Africa, Khoza (2020) notes a significant difference in the attitude of learners whose parents are digital natives from those whose parents are digital immigrants. Mkhasibe and Mncube (2020) believe that children whose parents are digitally native and have substantial educational backgrounds are more likely to support the introduction of remote learning initiatives than their counterparts. However, Mpungose (2020) argues against drawing a clear correlation between digital natives and digital immigrants but stress that learners' access to digital devices help them learn how to use remote learning platforms faster than their parents.

A Focus Theory of the Study

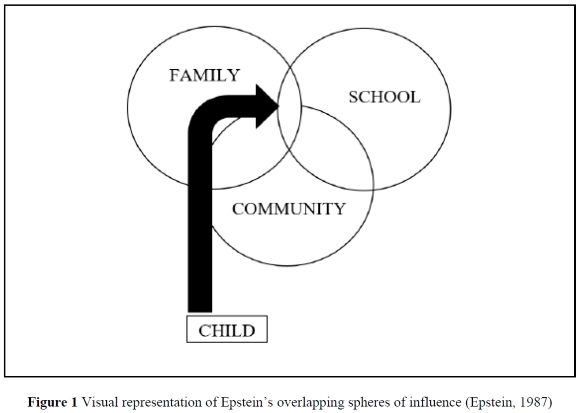

In understanding how to enhance the partnership between the SMT and the SGB in promoting digital technology and online learning platforms by learners, we adopted Epstein's (1987) theory of overlapping spheres of influence, founded upon Bronfenbrenner's (1979) ecological theory. This theory merges educational, sociological, and psychological perspectives to outline procedures for creating and sustaining successful partnerships between schools and families (Epstein, 1987; Myende, 2019). The universal vision of this partnership is viewed positively in empirical research as it acknowledges the role of numerous stakeholders in sustaining school functionality. According to Epstein (1987), this theory underscores four main components: family, child, school, and community. These model components can be pushed together or pulled apart based on forces such as technology, time, family dynamics, or philosophies of the school/family (Fantuzzo, Tighe & Childs, 2000:368). Therefore, each component must overlap to form partnerships with other components to help solve pressing challenges hampering curriculum implementation (Basson & Mestry, 2019; Epstein, Coates, Salinas, Sanders & Simon, 1997:80-85).

Epstein's (2005) theory of overlapping spheres of influence is of value since it argues for greater participation of all stakeholders in school governance for the effective delivery of quality education. As propounded by Basson and Mestry (2019), overlapping spheres of influence place a high value on learners, schools, parents, and the local school community working together to achieve all the stakeholders' desired outcomes. The SMT, through this framework, give the SGBs and parents who are digital immigrants the option to embrace digital technology for the benefit of the entire school. The participation of SGBs prompts parents to engage fully in school decisions and signals a greater cooperative approach between schools and all stakeholders whose interest is to promote school governance and the academic experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The overlapping spheres of influence invoke a sense of urgency from all interested and affected stakeholders to participate in meaningful activities shaping their children's education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Looking at the challenges faced by the SMT, the theory is relevant in providing "digital immigrants with a common understanding through which to address parents' hopes and discontent" (Mendieta, 2005:80).

The theory is also relevant as underpinning of this study because it argues for the most humanising influence - the one in which the SMT emerges as more human, more cautious, with greater respect for and more open-minded to signals and messages from diverse sources (Mahlomaholo, 2009:225). The theory, in short, contemplates, exposes, and questions hegemony and traditional power assumptions about relationships, groups, communities, societies and organisations to promote social change (Given, 2008:140). In the context of this study, an overlapping sphere of influence encourages the SMT to communicate, network and foster partnership with all stakeholders, including SGB members, to confront new realities of integrating technology into the teaching process. The responsibility of the SGB members is to enable a conducive environment for teachers to use remote learning platforms to enhance quality education in times of emergency. For instance, many SMTs' realities evaporate as they come across real teaching and learning situations that require adaptations, reflection and possible change using a different paradigm (Taole, 2013). As such, the SMT gets a mandate from all parents to introduce technological innovations meant to equip parents and teachers to improve quality education in a school. A partnership between the school and parents must articulate the extent to which parents ought to get involved as partners.

Aim of the Study

The aim with this study was to explore the perspectives of school governors and SMTs about the partnership to promote remote learning in schools located in deprived contexts in the uMkhanyakude district in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa.

To achieve the main aim of this study, the following questions were investigated:

• What are the perspectives of school governors and SMTs about the partnership to promote remote learning in schools?

• What influence does the partnership between school governors and SMTs have on the promotion of remote learning in rural schools?

Research Methodology

Research Context and Method

Remote learning is subject to controversy in rural schools, while progressive schools adopted remote learning as an ideal platform to continue curriculum delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, not all schools can integrate e-learning technology due to the strained relationship between SGBs and SMTs. The aim with this study was to explore how partnerships fail to promote remote learning and propose an alternative pathway to overcoming hindrances to participation between SGBs and SMTs. The unavailability of a guiding online learning policy for teachers and parents and the lack of training for teachers was also investigated as a possible cause for the delayed implementation of online learning.

This study was conducted during October and November 2020 in a few selected schools in the Hlabisa circuit in the uMkhanyakude district. From 33 schools in the circuit, we purposefully selected four schools. All these schools were still using the face-to-face approach during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic should have forced all schools to move all teaching online. Out of curiosity, it was interesting to understand the extent to which SGBs and SMTs became victims of the digital divide and establish what hindered their access to remote learning.

Data Collection Methods and Trustworthiness For this study we adopted a qualitative interpretive case study of four purposefully and conveniently selected schools who still used face-to-face teaching instead of remote learning despite the COVID-19 pandemic (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010; Yin, 2014). Interpretivism was used to understand and describe how SGBs and SMTs make meaning of their actions in their contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic (Creswell, 2014). An explorative case design was used to explore contextual conditions because we believe that they are relevant to the phenomenon under study. It also generated rich and deep descriptions of SMTs' and SGBs' experiences, which resulted in championing face-to-face rather than remote learning (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2000; Yin, 2014).

Two SMT members and two SGB members were selected from each of the four schools for a total of 16 participants. Of the 16 participants, four SMT and four SGB members participated in the focus-group discussion.

All participants electronically signed consent forms detailing all ethical issues (beneficence, anonymity, and confidentiality). To protect the participants' identities, pseudonyms were used. For example, the SMT members were coded as SMT1 to SMT4 and the SGB members were coded SGB1 to SGB4. Participants were required to complete an e-reflective activity one week before the Zoom focus-group meeting, followed by a WhatsApp one-on-one semi-structured interview which took about 45 minutes. The iCloud facility was activated to record meetings and interviews for easy transcription to enhance trustworthiness (credibility, confirmability, and transferability).

In terms of credibility, the study was first piloted as part of the pre-interview phase to determine the suitability of the iCloud facility to manage the process of recording and retrieval of data. This pre-interview phase was also used to test the interview questions and focus-group discussions to determine whether that led to the answering of the research questions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Interview tapes, videos, and transcribed texts were examined closely to ensure that we, as researchers, did not manipulate the data. This kind of reflection was necessary to ensure the trustworthiness of the findings and analysis process. In addressing transferability and conformability, we ensured that the results were reported systematically and carefully to show connections between the data and the results reported. However, this process can sometimes be tricky (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The services of a senior qualitative researcher in the Faculty of Education were used to manage the complex process of describing abstraction because it partly depends on the researcher' s insight or intuitive action, which may be difficult to explain to others.

Data were thematically analysed using inductive and deductive reasoning (Creswell & Poth, 2017). The data generated through the two research instruments were recorded and transcribed. Open coding was used to connect codes to categories. Deductive reasoning was used to map the codes onto the categories to form themes. The latter inductive process helped to recapture the remaining codes to form categories (Creswell, 2014).

Findings

With this study we aimed to explore the partnership between SGBs and SMTs in promoting remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The themes that emerged from the data generated from the interviews and focus-group discussions were: the role of SGB in promoting participative school activities, support that SMTs received from SGBs to promote remote learning, and roles and responsibilities of school governors. Subthemes that emerged under the last theme were the SGBs' involvement in school governance during the pandemic and collaboration between the SGBs and the SMTs to promote remote learning to improve quality education in schools.

The Role of SGBs to Promote Participation in School Activities

Most SGB participants seemed to indirectly fail to honour their role of promoting remote learning and, therefore, deprived their schools of a real chance of continuing with curriculum delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. In essence, the findings from the focus group with SGBs suggest that "most digital immigrants' parents' do not understand their roles and responsibility. SGBs further believed that meetings did not work because most parents always opposed their proposals to allow remote learning to continue." Thus, when SGBs become dysfunctional, the decentralisation process does not yield the desired results. The interview conducted with SMT1 and SMT2 supported this narrative:

It is a shame that parents do not want to use virtual platforms such as Zoom and Teams to attend urgent SGB meetings in our schools to discuss how to integrate remote learning despite multiple WhatsApp and SMSs inviting them to participate. The school can only afford to send SMSs [Short Message Service] as a means of communication, but the latter does not work as most parents do not heed a call from those SMSs. (SMT1)

In cases where parents have attended virtual school meetings, they hardly show any interest in the proposed online teaching approach. They don't read minutes sent to them via flyer or email (SMT2).

Parents refuse to support remote learning as such academic activities suffer. Therefore, the Minister of Basic Education may have to amend the SASA of 1996 as SGBs fail to govern in certain schools where meetings are postponed due to the absence of parents to form a quorum. (SMT1)

These responses coincide with the notion that some parents hardly supported schools in anything, including decisions to improve teaching and learning, claiming that it is the government's responsibility. The following was said during the focus-group discussion with an SMT: "If parents ignore their obligations during emergency periods, they miss a golden opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to learners' academic experience." In other instances, the future of their children was lost as they had the power to provide hardware resources and software applications to implement remote learning. Duku and Salami (2017) support the argument that parental involvement is non-negotiable, and that it strengthens participation in parent-teacher meetings about curricular activities.

Support that SMTs Received from SGBs to Promote Remote Learning

The respondents noted that leadership in school governance was in the hands of the parents. Their perspectives showed that parents as digital immigrants failed to understand the value of their involvement in school activities (Mkhasibe & Mncube, 2020). As an important institution, the school needs to evolve to safeguard the interest of community members, teachers, and learners. During the focus group the SGBs and SMTs agreed that "they work hard to provide quality education outcomes, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, things have been challenging as SMTs lacked support from SGBs." The COVID-19 pandemic had severely impacted the SMTs as they needed to continue with curriculum delivery through remote learning while observing social distance with the support from parents, as reflected in their interviews:

... as a matter of principle, parental involvement in school activities is mandatory to safeguard the integrity of the school. Parents in this community hardly support any initiative that aims to improve teaching and learning, and schools always receive very limited support. Still, most of them leave learners to us, hoping that we will teach them during the COVID-19 pandemic ... very sad. (SMT4)

As teachers, we don't have a good relationship with parents because they are not supportive of online learning initiatives which might save our lives. They refuse when they are called to purchase gadgets like desktop computers for their kids, citing financial difficulties. (SMT4)

Teachers feel that parent-teacher partnerships ought to provide platforms for interaction on an equal footing so that parents do not withhold their support in times of emergency. SGBs also have the mandate of dealing with budgetary functions that require parental input to be finalised for approval (Mestry, 2014). During a focus-group discussion, it was heart breaking to learn that "... schools in deprived contexts at times fail to requisition key resources such as learning and teaching support material (LTSM) or draw up the budget for school infrastructure during the COVID-19 pandemic.... "

Home-school partnerships are significant in supporting the SGB to provide oversight, necessary physical resources, and transparency in realistic budgets for the school (Poisson, 2014).

There has been a paradigm shift in parental involvement in post-apartheid education as parents in organised structures, including political parties, fought for recognition, but thereafter withdrew. The senior educator explored this further and stated:

Parents have failed to understand what they fought for during the apartheid era when they advocated people's education, as parental ignorance in education is apparent to every person, while the district empowers them with school governance and mandates them to support innovation and the integration of new technology in education. (SMT5)

It has been noted that parents ignore their responsibilities and fail to reflect on the potential damage caused to the child's academic success when teachers are not supported. This view was supported in the SMT focus group: "parental ignorance about the significance of remote learning cripple curriculum delivery and the probability of learners' academic success. Furthermore, it is, therefore, vital that the SGBs create an environment conducive to teaching and learning by supporting remote learning platforms beyond the current pandemic." The assertion of parental ignorance is supported by Van der Westhuizen et al. (2002) who argue that parents who are digital immigrants, by extension, lack basic instincts and general principles of how schools are run.

Roles and Responsibilities of School Governors SGBs' participation in virtual platforms to promote remote learning

In the data of this case study, parents alleged that the SGBs needed to be clear about their mandate on leadership, and ought to recruit parents with diverse expertise to support and advise the SMTs so that they can provide effective curriculum management. A general perception exists that parents withhold their expertise to meaningfully contribute to school governance, although their impact on learners' academic experience is well documented. This is how the participants expressed how they were identified and seconded to serve as SGB members but never participated in decision-making:

We partner with schools to promote effective school management. Despite attending meetings, we rarely contribute to major decision-making structures or witness the improved academic experience from our effort (SGB1).

It is shocking, to say the least, to me as chairperson of the SGB. The school would draft the agenda of the meetings without our contribution, and the principal would lead the meeting as though we had endorsed the agenda. Now, in such a situation, we only act as spectators as the SMT deliberates, while we sit on the side lines, confused. (SGB4)

[We are] not invited when the finance committee meets to draft and finalise the school's budget. No one bothers us with data and invites us as important members of the finance committee serving on the SGB (SGB3).

Even one of the most experienced SGB members, and a prominent supporter of the SMT, questioned the principal's behaviour and messages during some of the ongoing briefings. This point was advanced during the focus-group discussion, "our service to the school is like a window dressing because we are not taken seriously during deliberation; principals prefer to take a decision unilaterally." It was evident that SGB members required more training in order to understand their roles and responsibilities. One of the SGB members revealed that they have never attended induction training, let alone a government plan to integrate remote learning:

I am not alone; we insisted on attending briefings organised by the district to get an idea about the need for online learning. In these briefings, we are educated about the need for partnership between SGBs and SMTs, the need to collaborate with the SMTs, and how parents should change their behaviour during times of emergency. (SGB1)

The consensus is that the SGB needs to be empowered to better understand its role and responsibility in leadership so that its function is respected. This argument was emphasised during the focus-group discussion, "it has been noted that the effective management of the school as an institution is incumbent upon the SGB to govern effectively even during the COVID-19 pandemic where parents as digital immigrants drag their feet." Therefore, parents need to honour their obligations in terms of the SASA to reap the benefits of their commitment to school activities, including monitoring their children's behaviour and academic experience.

The partnership between SGBs and SMTs to improve remote learning

The results reveal that schools in deprived contexts suffered from an institutional leadership crisis, which inadvertently impacted school governance and learners' academic experience. Mosoge, Challens and Xaba (2018) hold that when SGB members do not understand their mandate, the SMT tends to get distracted from the core mandate which is curriculum supervision. The SGB members demonstrated this confusion during a focus-group discussion, "who felt that they are not empowered to participate in a technical discussion involving the decision to integrate new technology in the curriculum delivery. In our view, the introduction of remote learning requires enormous investments and as parents, we cannot afford smartphones, data, and software applications. When asked about their core mandate, their responses left more questions than answers." In a surprising response an SGB member assured us that the principal assumed the sole responsibility of making the final decision:

As much as we have ideas to support the SMTs' desire to promote remote learning, the principal sometimes overrules and dismisses our initiatives. Well, as you can imagine, the majority of us are not educated, and when it comes to online learning, we are called digital immigrants, so we don't have any leg to stand on. What we can say is that we do our best to partner with schools as the elected representative of the community to uphold and promote the interest of our school, and despite attending meetings where the agenda is pre-planned, we try to meaningfully engage the SAAT in decision-making and suggest solutions that will improve learners' academic experience as part of our mandate. (SGB1)

As you can imagine, we have a very limited role to play in supporting the school in the introduction of remote learning, let alone impacting learners' academic experience. Understandably, most parents in this community are not taking education issues seriously. They will tell you that there are many urgent, pressing, and competing demands to attend to as they are unemployed rather than to come here to listen to online learning. Parental involvement is weakened by parents' feelings of helplessness. As you can see by the level of information we have about it, the running of the school is very poor. (SGB2)

The respondents noted that effective instructional leadership was core to the schools' fundamental business of teaching and learning. Quite frankly, the SGBs and parents must collaborate on major policy standpoints by encouraging curriculum management. The claim was repeatedly made that parents were key players in maintaining effective instructional leadership, as schools were dependent on parents as the primary teachers of children.

It was evident from the results that SGB members in deprived contexts were mindful of their shortcomings in helping the school with instructional leadership. The frustration was caused by poor levels of education and bureaucratic challenges in the educational system, which created a high level of anxiety and a feeling of helplessness.

Most SGB members don't read the minutes of the previous meeting before attending the next meeting virtually (SMT3).

Our level of education and literacy is too low. There is nothing the school can do to assist us; honestly, it's too much for the school to intervene (SGB).

By law, the SGBs must participate in institutional decision-making processes, as the schools cannot alone decide on certain aspects, i.e., integration of remote learning and curriculum management (RSA, 1996a).

Discussion

The research findings reveal that schools had sometimes failed to work with parents to introduce innovation and new technology needed to improve school governance (RSA, 1996a). Parents and teachers agree on the need to integrate remote learning in teaching and learning as part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is worth noting that parents who are digital natives support their children's academic shift from face-to-face to remote learning. The academic efficacy of schools in deprived contexts depends on strong SGB leadership in embracing new technology and learning platforms. As Mosoge et al. (2018) argue, schools' academic success depends on the SGBs' ability to support SMTs' initiatives of implementing innovations during an emergency. While the school expects a lot from the SGB, it is apparent that the structure is led by digital immigrants who are frustrated by bureaucratic challenges in the education system. As a result, SGB members feel helpless and fail to support the school in realising the aims and objectives of integrating remote learning to improve quality teaching and learning.

The question that frustrated most SGB members was how to forge a partnership based on trust with SMTs to promote remote learning. Basson and Mestry (2019) and Youngs (2017) argue that the SGB's role is daunting and cannot be underestimated, as it includes promoting technology of the 21st century aligned with the aims and objectives of the school, after which the SMT ought to emerge with procedural decisions to implement the SGB's decisions. The findings show that parental involvement was implied in school governance, and sometimes parents were frustrated by questions about the affordability of cutting-edge technology. It was evident from the findings that bureaucratic challenges (subscription fees to access online learning platforms and a lack of credit facilities to pay for online learning platforms) rendered their efforts futile, thus fuelling the notion of weak leadership on their part. In short, SGBs led by digital immigrants felt isolated by the very system that created this legitimate structure, which is why they appeared at times not to have plans to integrate remote learning and improve learners' academic experience.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In this study we explored participation between the SGBs and SMTs in promoting remote learning and academic experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study cannot be generalised to all SMTs and SGBs in South Africa. The main reason for this is that this study was limited to four schools. To achieve the main aim of this study, the following questions were answered:

• What are the perspectives of school governors and SMTs about the partnership to promote remote learning in schools?

• What influence does the partnership between school governors and SMTs have on the promotion of remote learning in rural schools?

Based on the study we conclude that SGBs do not fully participate in the key decision-making process when they are most needed. They do not understand the importance of their role in implementing the school' s core mandate, which is to promote an enabling environment for academic activities within the school, including support for the implementation of online learning. Secondly, the SMTs need support from SGBs to implement remote learning on a full scale, however, most parents in rural areas are digital immigrants. The amount of pressure from the DBE and other stakeholders weigh heavily on SMTs to implement curriculum measures under strict COVID-19 protocols with little parental support. Thirdly, the parent-teacher partnership must be revisited to provide the right platform for interaction. Such platforms should encourage parents against withholding their support due to a lack of information in times of emergency. In the fourth place, the conclusion reached is that SGBs need targeted empowerment initiatives to improve their leadership roles and responsibilities to execute their function optimally.

Based on these conclusions, the following recommendations are made. SGB members need to familiarise themselves with the benefits of online technology platforms available to encourage parents to support remote learning for their children. Secondly, the SMTs should arrange virtual meetings with SGB members to build confidence in the basic use of technology. SMTs must develop strategies to use existing digital resources such as WhatsApp, Twitter etc. optimally to benefit SGB committee members so that they will find it possible to communicate with parents and allay their fears. The overlapping role of principals impacts the partnership between SMTs and SGBs, wherein principals, as members of SMTs, encourage SGBs to embrace digital technology for the benefit of the entire school. The SMTs, on the other hand, must push for the integration of remote learning into the curriculum to harness the needed partnership with parents to encourage remote learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was also noted that despite the SGBs having fears about technology, they had begun to understand the importance of their participation in supporting the introduction of technology and working with SMTs to improve learner performance. In a nutshell, we recommend that parents should support remote learning for learners to achieve quality education beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Where stakeholder discourse in schools is clear, parents work to support SMTs to introduce innovations. At the same time, SMTs hold a school functionality mandate, which, among other things, includes promoting remote learning to advance quality education and academic experience for learners.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education that allowed us to conduct the research in public institutions; the former circuit manager, district officials, the principals, educators of the schools concerned; parents and community members for making our study a success. We thank the King Cetshwayo Education district and the Esikhaleni circuit officials for allowing us to meet with them as part of data generation, and Dr Ngema and her former colleagues for their assistance with study administration.

Authors' Contributions

D. Mncube and B. Ntuli conceptualised the article and were involved in the data collection process while D. Mncube was tasked with data analysis and interpretation of results. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alhassan AB 2016. Parents and school proprietors frustrating national education policy: What should stakeholders do? IFE PsychologIA: An International Journal, 24(2):259-266. [ Links ]

Basson P & Mestry R 2019. Collaboration between school management teams and governing bodies in effectively managing public primary school finances. South African Journal of Education, 39(2):Art. #1688, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1688 [ Links ]

Bayat A, Louw W & Rena R 2014. The role of School Governing Bodies in underperforming schools of Western Cape: A field based study. Aediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27):353-363. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p353 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2000. Research methods in education (5th ed). London, England: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Creswell JW & Poth CN 2017. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dube B 2020. Rural online learning in the context of COVID 19 in South Africa: Evoking an inclusive education approach. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2): 135-157. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2020.5607 [ Links ]

Duku N & Salami IA 2017. The relevance of the school governing body to the effective decolonisation of education in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 35(2):112-125. https://doi.org/10.18820/25193X/pie.v35i2.9 [ Links ]

Duma MAN 2014. Engaging rural school parents in school governance: The experiences of South African school principals. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27):460-166. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p460 [ Links ]

Epstein JL 1987. Toward a theory of family-school connections: Teacher practices and parent involvement. In K Hurrelmann, FX Kaufmann & F Lösel (eds). Social intervention: Potential and constraints. New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Epstein JL 2005. Attainable goals? The spirit and letter of the No Child Left Behind Act on parental involvement. Sociology of Education, 78(2):179-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070507800207 [ Links ]

Epstein JL, Coates L, Salinas KC, Sanders MG & Simon BS 1997. School, family, and community partnerships: Your action handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Fantuzzo J, Tighe E & Childs S 2000. Family Involvement Questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2):367-376. [ Links ]

Given LM (ed.) 2008. The Sage encyclopaedia of quantitative research methods (Vol. 1 -2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Khoza SB 2020. Students' habits appear captured by WhatsApp. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(6):307-317. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n6p307 [ Links ]

Lincoln YS & Guba EG 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Mahlomaholo S 2009. Critical emancipatory research and academic identity. Africa Education Review, 6(2):224-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146620903274555 [ Links ]

McMillan J & Schumacher S 2010. Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Mendieta E (ed.) 2005. The Frankfurt school on religion: Key writing by the major thinkers. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mestry R 2014. A critical analysis of the National Norms and Standards for the School Funding policy: Implications for social justice and equity in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(6):851-867. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214537227 [ Links ]

Mestry R 2020. The effective and efficient management of school fees: Implications for the provision of quality education [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 40(4):Art. #2052, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n4a2052 [ Links ]

Mkhasibe RG & Mncube DW 2020. Evaluation of pre-service teachers' classroom management skills during teaching practice in rural communities. South African Journal of Higher Education, 34(6):150-165. https://doi.org/10.20853/34-6-4079 [ Links ]

Mncube V, Davies L & Naidoo R 2014. Democratic school governance, leadership and management: A case study of two schools in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development in Africa, 1(1):59-78. https://doi.org/10.25159/2312-3540/45 [ Links ]

Mohapi SJ & Netshitangani T 2018. Views of parent governors' roles and responsibilities of rural schools in South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1):1537056. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1537056 [ Links ]

Mosoge MJ, Challens BH & Xaba MI 2018. Perceived collective teacher efficacy in low-performing schools. South African Journal of Education, 38(2):Art. # 1153, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n2a1153 [ Links ]

Mpungose CB 2020. Beyond limits: Lecturers' reflections on Moodle uptake in South African universities. Education and Information Technologies, 25:5033-5052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10190-8 [ Links ]

Myende PE 2019. Creating functional and sustainable school-community partnerships: Lessons from three South African cases. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(6):1001-1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143218781070 [ Links ]

Ndebele M 2015. Socio-economic factors affecting parents' involvement in homework: Practices and perceptions from eight Johannesburg public primary schools. Perspectives in Education, 33(3):72-91. [ Links ]

Nhlabati MN 2015. The impact of parent involvement on effective secondary school governance in the Breyten Circuit of Mpumalanga. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79170889.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Ntseto RM 2015. The role of school management teams (SMTs) in rendering learning support in public primary schools. MEd dissertation. Bloemfontein, South Africa: University of the Free State. Available at https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11660/2320/NtsetoRM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Okeke CI 2014. Effective home-school partnership: Some strategies to help strengthen parental involvement. South African Journal of Education, 34(3):Art. # 864, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201409161044 [ Links ]

Poisson M (ed.) 2014. Achieving transparency in pro-poor education incentives. Paris, France: International Institute for Educational Planning. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226982. Accessed 23 November 2021. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996a. Act No. 84, 1996: South African Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 377(17579), November 15. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996b. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Taole MJ 2013. Reflective practice through blogging: An alternative for open and distance learning context. Journal of Communication, 4(2): 123-130. Available at http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JC/JC-04-0-000-13-Web/JC-04-2-000-13-Abst-PDF/JC-04-2-123-13-065-Joyce-T-M/JC-04-2-123-13-065-Joyce-T-M-Tt.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen PC, Basson CJJ, Barnard SS, Bondesio MJ, De Witt JT, Niemann GS, Prinsloo NP & Van Rooyen JW 2002. Effective educational management. Cape Town, South Africa: Kagiso. [ Links ]

Xaba MI 2011. The possible cause of school governance challenges in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 31(2):201-211. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n2a479 [ Links ]

Yin RK 2014. Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Youngs H 2017. A critical exploration of collaborative and distributed leadership in higher education: Developing an alternative ontology through leadership-as-practice. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(2): 140-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1276662 [ Links ]

Received: 15 April 2020

Revised: 16 July 2022

Accepted: 22 December 2022

Published: 28 February 2023