Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.43 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43n1a2144

ARTICLES

Learner support for reading problems in Grade 3 in full-service schools in the Gauteng province

Thembi Phala

Department of Early Childhood Education, College of Education, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. phalatal@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, the issue of learning to read is an area of concern. While studies have focused on reading problems in the Foundation Phase, little is known about this issue in full-service schools. In light of this, the aim of this study was to explore how Grade 3 teachers supported learners who experienced reading problems in full-service schools. Vygotsky's sociocultural theory was used to understand the meaning-making of Grade 3 teachers in the context of reading. This qualitative study with a case study design was conducted in 3 full-service schools in the Tshwane North district in the Gauteng province. Participants included 6 learner-support teachers and 11 Grade 3 class teachers. Data were produced using semi-structured interviews. The findings show that the methods of reading and modes of working to support learners are complex, varied, and largely teacher-driven. This set of circumstances highlight the need for co-construction of reading with learners and the addressing of specific barriers to learning to read. This was somewhat evident among the specialist teachers but not sufficiently robust. This study raises questions for professional development for reading problems in the Foundation Phase.

Keywords: full-service schools; Grade 3; reading problems; support; Vygotsky

Introduction and Background

Reading is fundamental to almost all formal learning (Spaull, Van der Berg, Wills, Gustafsson & Kotzé, 2016:13). It is a skill that cannot be acquired naturally and requires systematic and well-informed instruction (Department of Education [DoE], 2007:8). In schools, Grade 3 teachers are expected to teach learners to read. The process for learning to read is developmental. Learners follow the same pattern and order of reading behaviour along a continuum (Pretorius, Jackson, McKay, Murray & Spaull, 2016:16).

During the reading process, learners are expected to process what they are reading cognitively so that they can give meaning to it (Gillet, Temple, Temple & Crawford, 2012:436). But, for learners who struggle to process information, this might create challenges, as they might experience difficulties in understanding what has been read and may also be unable to read proficiently.

The inability to read proficiently has several negative results. It is related to a high number of learner dropouts, which hampers individuals' learning potential as well as the nation's competitiveness and general productivity (Fiester, 2010:1). In the same vein, Townend and Turner (2000:274) support this view and highlighted that inadequate reading skills also result in poor academic progress, which impedes the general development of learners. In addition to the repetition of grades, there is also the danger of social isolation among learners.

Current studies reveal that learners in South Africa are falling behind and are failing to grasp basic reading literacy skills. According to the studies conducted by the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), South African learners performed the worst among the 50 countries that took part in the assessments. In 2011, the findings revealed that 61% of learners could not read or write at the appropriate age level. In 2016, it was found that 78% of Grade 4 learners could not read for meaning in any language, and thus these learners performed at 320 points, which was below the 400 points minimal benchmark (Howie, Combrinck, Roux, Tshele, Mokoena & McLeod Palane, 2017:2). However, a critical analysis of standardised testing such as PIRLS for South Africa show the biggest challenge of contextualising and translating items into the 10 official languages (Howie, Venter, Van Staden, Zimmerman, Long, Du Toit, Scherman & Archer, 2008:15).

Furthermore, in 2000, 2007, 2013 and 2017, the Southern and Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) conducted a survey which found that South African Grade 6 learners' reading scores were 492, 495, 558 and 538 respectively (Bandi, 2016:2, Department of Basic Education [DBE], Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2017:4), which means that South Africa hovers around the SACMEQ average reading score of 500.

Another study was conducted by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which assessed the quality of both numeracy and literacy. From the study, it was discovered that 9% of Grade 4 learners performed at an advanced reading level, 37% at proficient level and 68% far below a proficient reading level (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2017:1). Furthermore, the Annual National Assessment conducted in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 for learners in Grades 2 to 7 for both literacy and numeracy also showed low scores. These results are very concerning.

As in South Africa, the lower and middle countries also experienced the same challenges with regard to the learners' reading scores. According to Azevedo, Crawford, Nayar, Rogers, Barron Rodriguez, Ding, Gutierrez Bernal, Dixon, Saavedra and Arias' findings, 53% of all children in lower and middle countries are considered "learning poor" (Azevedo et al., 2019:16). Learning poor refers to children who read below the minimum proficiency level at the end of primary school (age 10-14) (Azevedo et al., 2019:16). The findings also revealed 87% learning poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. This rate was 13% higher than that in World Bank-client countries in Europe and Central Asia.

Given the background indicated above, the issue of learners reading below the minimum proficiency level is not a unique phenomenon to South Africa - it is a continental and global phenomenon as a certain percentage of the population, even in rich countries, experience reading problems (Jackson & Kiersz, 2016; Martin, Mullis & Foy, 2016). However, the contexts present these problems and opportunities in different ways.

In literature, the concerns for low learner performance in South Africa can be partly attributed to how Foundation Phase teachers are prepared to support reading in their classrooms. It was noted that teachers were not prepared on how to teach reading - particularly in the home language (DoE, RSA, 2008:11; Pretorius et al., 2016:2). This means that the professional development for teachers on how to teach and support learners experiencing reading problems is still an issue of concern. In light of the concerns about low performance and inadequate teacher knowledge to support learning to read, with this article we expand the literature on reading problems to a context-based understanding of how Grade 3 teachers support learners who experience reading problems in full-service schools (FSS). These schools are particularly geared towards offering additional support for learners experiencing reading problems.

Literature Review

Learners experiencing reading problems are frequently referred to as struggling readers. According to Hall (2014), these learners commonly read at least 1 year below their present grade level and do not have any recognised learning disabilities. The term "reading problems" is often used interchangeably with terms such as reading challenges and reading difficulties. Reading difficulties, according to Paratore and Dougherty (2011:12), are regarded as "an unforeseen reading failure that cannot be accounted for by other disabilities." The term "reading problems" will be used throughout this article.

In literature, commonly identified reading problems include (1) reversals or swapping of letters, (2) regression, which happens when the learner's eyes move back to words that have just been read, and (3) skipping of words which happens when the learner omits or excludes some words while reading a text. "These words may be too difficult for the learner to read or they may have unintentionally not paid attention to them" (Joubert, Bester, Meyer & Evans, 2013:146-147). Adding to the problems mentioned above, Le Cordeur (2010:78) records four main challenges for learners experiencing reading problems. These challenges are a lack of vocabulary, inadequate reading fluency, negative attitudes towards reading, and poor reading comprehension. Considering the above, it is important for teachers to take note of these challenges to be able to select effective reading strategies for diverse learners' reading needs.

Selecting effective reading strategies that are responsive to individual learners' reading needs may be problematic for some teachers. "Reading strategies embrace the conscious, internally variable psychological techniques that aim at improving the effectiveness of or compensating for the breakdowns in reading comprehension, in specific reading tasks and in specific contexts" (Karami, 2008:5). They are "ways of solving problems that the learners may come across while reading" (DoE, RSA, 2008:19). From literature, the most commonly distinguished and suggested strategies are "reading aloud, independent reading, shared reading, paired reading, group guided reading, and paired reading" (DoE, 2007:19-27; Place, 2016:73).

Several studies have been conducted on how teachers can improve learners' reading abilities with reference to the types of reading methods (Lawrence, 2011; Lee, Gable & Klassen, 2012; Mule, 2014). For example, in a micro-genetic study conducted by Lee et al. (2012:824), the findings reveal that learners with learning difficulties require alternative instruction methods. The research shows that learning by phonemic association through a computer keyboard, identifying the individual words of the sentence, and using visual memory, meaning clues and linguistic clues were among the effective methods for improving learners' decoding abilities. Supporting the findings above, the five reading methods indicated below were identified and used in the literature.

In the alphabetic method emphasis is placed on the importance of knowing the letters of the alphabet before the learner can read a particular language. This method permits the learner to identify letters and to understand that letters of the alphabet are written symbols that can be learned and named individually (Hugo & Lenyai, 2013:4). Vacca, Gove, Burkey, Lenhart and McKeon, (2011:164) regard alphabet knowledge as an excellent predictor of success in early reading. However, for learners struggling to distinguish the difference between the letters of the alphabet, this method might not be of much help.

The phonic method accentuates the need for learning the individual letters and sounds of the letters before reading single words. This method allows learners to understand the relationship between the sounds of spoken language and the letters that present those sounds in written language (Choate, 2004:70; DBE, 2010:27). Consequently, they will realise the correspondence between the sound and the letter and letter combinations in their particular language. Phonics, therefore, prepares learners for fluent reading. However, based on the explanation provided, teachers who opt for this method should understand that not all learners experiencing reading problems would benefit from the method. For example, from a study conducted by Spear-Swerling (2016:520) on common reading patterns, "it was found that learners with specific word reading problems and mixed reading problems do not always benefit from the phonic method."

The language experience method allows learners to share and discuss their experiences, listen and tell stories, and dictate and write words independently (Vacca et al., 2011:124). By applying this method, learners' own understanding of language are founded on their real-life experiences. Teachers who use this method can teach both reading and writing simultaneously. Sight vocabulary and word recognition play an important role in this method. Words are used to construct sentences relating to narrated stories.

The look-and-say method or global method requires learners to learn the entire word and not the parts (sounds). Thus, this method recognises the geometric shape of the words and not the individual recognition of the letters. Considering this, this method depends on learners' visual memory and, should the learners fail to recognise the word, they will be lost (Joubert, Bester & Meyer, 2008:91). When using this method to support learners experiencing reading problems, teachers use flashcards with words, sentence strips, and story cards (Joubert et al., 2014:111). Should the teacher opt to use this method, visual learners who learn best through seeing things will be advantaged more than learners who prefer auditory and kinaesthetic learning styles.

Lastly, the eclectic method or combined method holds promise as it combines the phonic and the look-and-say methods. It uses words and sentences as its point of entry which suggests that a meaningful whole is used. This makes learners realise that letters, which have sounds form words. The eclectic method has the following benefits. Firstly, it introduces learners to strategies for unlocking words (for example, sounding); and secondly, it accommodates different learning and reading styles (Joubert et al., 2014:112). If teachers use this method, diverse learners with different reading needs will be accommodated. Carroll, Bradley, Crawford, Hannant, Johnson and Thompson (2017:29) argue that a methodology that consolidates phonics with oral language instruction and sight-word learning can be valuable for learners experiencing reading problems.

The review informed the methods that the participants in the study were using. It also helped to identify modes to support learners with reading problems. In this way we were able to establish a complex, varied, and teacher-centred approach to supporting learners with reading problems.

Theoretical Framework

This study is informed by social constructivism guided by Vygotsky's (1978) concepts of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), mediation, and cultural tools. Social constructivism emanates from a sociological perspective of theorising the world. Its greatest contribution to education lies in the fact that it posits that human development is socially situated (McKinley, 2015:184). This means that the construction of knowledge does not emanate from predetermined laws of a phenomenon in a prior way, but from interactions of key people that have a vested interest in making meaning in a specific context. The study reported on in this article was about with Grade 3 teachers and their meaning making with special reference to learner support for reading problems. Hence, the teacher is viewed as a social actor who has the capacity to act in a variety of ways to support learners with reading problems. This is captured in the concept of teacher agency.

The chosen concepts of ZPD, mediation, and cultural tools help to explore learner support in a way that power for action can be attributed to the teachers and the way in which they include the learners' voices. Ideally, there should be a co-construction of knowledge between the teacher and the learner. Vygotsky (1978) emphasised the role of the social context of learning and believed that learners construct their own knowledge through interaction with their environment (Conkbayir & Pascal, 2014:80). During the interaction, both the teachers and learners are in collaboration and this allows meaning to be co-constructed.

For Vygotsky (1997), teachers are directors of the social environment in their classrooms, the governors and guides of the interactions between the educational process and the learner (Verenikina, 2008:166). The emphasis is to shift from what the teachers must do to how the teachers are going to do it. The guided interactions create opportunities for learners to be active agents rather than passive recipients of learning.

According to Vygotsky (1978), learners learn new knowledge and skills best when they are working in their ZPD. The ZPD refers to "the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem-solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers" (Vygotsky, 1978:86). This implies that there is a gap between what learners can do independently and what they can do with the help of an adult or a capable peer. The idea is to ensure that the learners reach their potential through scaffolding - working with teachers or more knowledgeable peers to achieve their learning goals (Hammond, 2001). Scaffolding provides learners with the opportunity to use their existing knowledge to internalise new knowledge. It is, therefore, the task of the teacher to provide learners with activities that will require activation of prior knowledge to learn new knowledge through guidance.

The scaffolding of learning requires the use of cultural tools - characteristics that define how humans interact and make meaning (Conkbayir & Pascal, 2014:80). Vygotsky identified two forms of cultural tools, namely, physical and psychological tools. The former entails computers, books, and other materials, whereas the latter entails language and thought. For the full impact of scaffolding and the use of cultural tools to support interactions and dialogue, the teacher has to use mediation.

According to Wertsch (2002:105), both the action and mind are influenced partly by the mediational means that a person would use. Within the ZPD, both teachers and learners will be active but this will depend on the teacher's expertise. The learning should be intentionally targeted. There has to be the use of language, specific methodological approaches and/or resources such as books and displays. This helps learners to build the cognitive capacities necessary for a "reading child." Teachers would then have to pay careful attention to learners' ZPD, cultural tools, and positionality as agents who have mediational means.

All of the above concepts were helpful in providing a more nuanced understanding of how teachers support learners experiencing reading problems in FSS.

Methodology

Study Design

This article is based on part of a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) study in which reading support for Grade 3 learners in FSS was explored. A qualitative research approach with a case study design was deemed most suitable for this study as I sought to gain a greater understanding of how people make sense of the contexts in which they live and work (Bertram & Christiansen, 2016:26). The case study design helped to view the selected schools in which the teachers performed their work as bounded settings.

Sample and Study Site

The chief education specialist in Gauteng recommended schools for the study. Purposive sampling was used to select three FSS in the Tshwane North district in Gauteng. They are referred to as Schools A, B, and C. All schools had the basic infrastructure. African languages was used as the language of learning and teaching (LoLT) except in School C, were the LoLT was English. The participants were selected on the basis of experience in teaching Grade 3, training received in relation to supporting learners with reading problems, and also their availability and willingness to participate in the study. In total, 17 Grade 3 teachers (six learner support teachers and 11 Grade 3 class teachers) were selected. Learner support teachers are referred to LSTs and Grade 3 class teacher are referred to GR3CT. All participants were female and professionally trained teachers. However, the participants were different in terms of home language, qualifications, and years of teaching experience in Grade 3 in a full service-school. A pilot study was conducted to test the research questions and identify issues that were important for inclusion. This resulted in a revision of some questions.

Data Collection Method

Semi-structured interviews which consisted of open-ended questions were used as data collection method. This permitted the participants to express their personal perceptions and opinions of how Grade 3 teachers can provide effective reading support for learners experiencing reading problems in FSS. The interviews with participants took place after their normal teaching time for approximately an hour each over a period of 3 weeks. I started by interviewing six learner support teachers and then the 11 Grade 3 class teachers.

Data Analysis

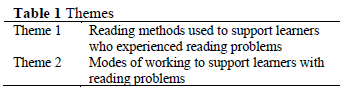

Data analysis is a technique used to structure, bring order and give meaning to data collected (De Vos, Strydom, Fouché & Delport, 2011:397). For this article, I revisited the data set and analysed it using thematic analysis as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006), which includes the following six steps: "familiarising yourself with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report" (Braun & Clarke, 2006:87-93). I started by listening to the recorded responses of the participants gathered during the interviews and transcribed the data. I read and reread the data set. The data were categorised using the colour-coding analytical system (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This helped to identify the units of meaning which were then clustered. From this, patterns emerged and themes were identified, reviewed and named as indicated in Table 1.

The above themes are discussed in the results section.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the institution's ethics review committee. Informed consent was obtained from the Gauteng DoE, the principals, and the teachers. As the interviews progressed, it was also important to ensure that participants were well informed about the specific research activities and that they had a right to participate or withhold participation without any disadvantage. Once participants were clear about the research activities, they were forthcoming in their responses.

Results

The results present two themes that make explicit the support the participants offered to the learners. The reading method and the modes of working shed light on how learners were supported.

Reading Methods Used to Support Learners who Experienced Reading Problems

Reading problems are complex. Research suggests that no one method will work for all learners (DoE, 2005). In my study, an eclectic mix of methods and dominant methods came to the fore. GR3CTs and LSTs explained how they preferred an eclectic mix of methods to support the learners to read. These methods were explained as phonic, flashcards, picture, drill, and tactile methods. Phonics was the commonly preferred method. It was evident that teacher-centred approaches in very controlled environments were favoured. Interactions with the learners were done within the ambit of the teacher-created goals for readings.

GR3CTs and LSTs opted for the phonic method. This method is about a predictable relationship between the sound of spoken language (phonemes) and the letter that present those sounds in written language (graphemes) (Choate, 2004:70; DBE, 2010:27) The excerpt shows a part of the whole method of teaching phonics. LST3 indicated that she introduced the sounds of the letters before learners were allowed to name the word. Once the learners knew how to sound the letters, she afforded them a chance to name the word. In this way, the learners learned the skill of encoding and decoding words. The choice of the method was driven by the teacher and the suitability for all learners was not questioned: "... reading the method that I am using and happy with is to lay the foundation of the sounds and then to name them the way they are ... the phonics method" (LST3).

Similarly, LST1 and GR3CT4 stated that they used the phonic method as the entry point to teach sounds. These participants, however, extended their approach with picture reading. This type of scaffolding is helpful for learners struggling to read as the pictures provide clues. LST1 taught learners to sound of the word and followed this by showing the learners a picture so that they could interpret it. Once they knew how to interpret the picture, the teacher removed the picture to assess whether the learners could remember or recall the word. This approach made demands on visual perception and information processing. The excerpt below illustrates this.

So I start teaching them to sound the word or maybe show them the picture to interpret the picture like this picture represent this and after that we maybe shift the picture and try see if the learners can remember or recall the word. (LST1)

GR3CT4, on the other hand, provided more details on her phonic-based method. In her response, she said that she taught the phonic sound first. She then drilled the sound by using pictures. Thereafter, she used the phonic charts to build the words. After she built the words, she cut the words into syllables. She then included the picture to assist learners to understand and remember the words. GR3CT4 hence paid more attention to the processes to allow for recall. While this is helpful, some learners might have problems with information processing. This, however, did not feature in her response below.

... we start with phonic sounds and drill them. You use pictures, you use phonic charts, you build the words, you cut the words into syllables so that the learner can understand. You must also include the picture so that the learner does not forget. (GR3CT4)

GR3CT9 provided a more practical way of using pictures to emphasise the sounds in order to facilitate understanding. In her response, she read the letter and the word and then placed the picture with the similar sound next to the letter.

. maybe with the support of a picture for the learner to have a clear understanding of what that letter is all about. For example, when I say 'a, ' I will say 'a ' for apple and I will put a picture of an apple next to ' a' so that she will be able to identify that this is ' a' letter and ' a' can be associate with apple because the word apple starts with the letter 'a. ' (GR3CT9)

The above were not the only methods used by participants. GR3CT1 and GR3CT11 indicated that they used flashcards to support the learners to read. GR3CT1 used flashcards to emphasise the sound that the learners could not understand whereas GR3CT11 used flashcards to afford the learners opportunities to spell and blend the words.

... if the learner doesn't understand the sound ' mph' together you must take it one by one and take the flash card and show the learner (GR3CT1).

With regard to the methods, I use the flash cards. Then I allow the learner to spell and to blend when reading (GR3CT11).

From the interviews there was also evidence of the use of tactile methods. GR3CT1 highlighted that she used the method to allow the learners to touch and feel. She started by drawing the letter in the sand and then asked the learners to follow the shape of the letter. By so doing she allowed the learner to associate the sound with what they felt in the sand.

... you can even use tactile method. Like you tell the learner that this sound is 's. ' By tactile [methods], you are going to use the teaching aid whereby you put maybe sand and draw ' s' on the sand and the learner must touch the sand and feel it and follow the drawing and say the sound ' s' several times. (GR3CT1)

Modes of Working to Support Learners with Reading Problems

When learners experience reading problems, it is important to consider the different modes of working in order to identify the problems and to support learners whose specific problems have been identified. In the study, I found different responses to how Grade 3 class teachers approached learners with reading problems and how the learner support teachers dealt with them. This was expected given their generalist and specialised roles. The Grade 3 teachers had workshops on reading using the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement curriculum. During these workshops, the teachers were introduced to modes of working to support reading and to identify learners with reading problems. The Grade 3 teachers had to reinterpret the information from the workshops and apply it in the context of their practice. Different modes of working were used by the Grade 3 teachers to scaffold learners with reading problems. GR3CT1 indicated that she used group teaching with a phonic-based approach. As an entry point, she used sounds to help learners read. Once they had mastered the sounds, she gave them an opportunity to do shared reading. Working in this way gave her insight into who was experiencing problems. She then attended to them individually. The excerpt below illustrates this.

... as an educator you start with group reading. Group reading is whereby you are going to introduce something like a sound or phonics so when you introduce it, you introduce it in the groups. After introducing that in a group, maybe the children may learn and they read together. [This] is shared reading and maybe sometimes if that group can read, you take them individually. (GR3CT1)

GR3TC3 mentioned that she divided her class into groups. She used the whole word/flash method of shared reading with groups. She wrote the word on paper and showed it to all the learners. She then read the word to all the learners and told them to read it together. She then moved around each group showing and reading the word to the learners. She then afforded the learners opportunities to read the word as a group and then as individuals. As the learners read individually, she then identified those learners who were experiencing reading problems.

Again I do shared reading. Like you show them something written on a paper; you show group by group and you read for them. Then, they will read after you then you do it group by group. Then after that, they will read one by one. They will not read all of them in the same day, the others will read the next day: that is how you pick up the problems. Immediately they read one by one is like learning is taking place - everyone wants to read. Ya, especially when others are listening to them they become so like ' I can read.' (GR3CT3)

In contrast, GR3CT5 used group teaching to teach learners but this was not her entry point. She used phonics and independent reading and periodically used group reading to foster confidence in the learners. She felt that the diagnostic approach was more appropriate: "I usually use the phonics, vowels and independent reading. Sometimes, I tell them to read in groups so that the learner can have faith in himself or herself" (GR3CT5).

All the FSSs in the study had Learner Support Teachers (LSTs). These teachers attended to learners in groups of 12. The LST participants described a more structured approach to supporting the learners, as they were specialists in dealing with barriers to learning in mathematics and reading. In the excerpts, LST1 illustrated how she structured and adapted group teaching. In her response, LST1 used reading as a whole class (12 learners) as a starting point for supporting learners to read and then followed this by learners reading in small groups (four learners). She then paired learners according to their different reading abilities so that they could support each other. Once they were feeling secure and competent, they read individually. During the individual reading, she identified the learners who struggled to read. In order to be responsive, she changed her method to suit the learners as illustrated below.

Again in class, when we also read we start by reading as a class (large), then as a group and I will also pair them where I pair the learner who is average with the one who is struggling and also asked them to read individually, so I will see which learners are still struggling and I have to change the method. (LST1)

There was also evidence of group support programmes. In order to allow learners to experience commonality of responses from their teachers, LST5 indicated that they used documentation from the teachers and their own screening tools to group learners according to the barriers they experienced in reading. Those learners that did not fit any of the common categories received individual support.

In our classroom we use a group support programme because we group those learners according to the problem that they experience and, after that, we identify if there are those learners who are not at the same: who don't have the same problems as these learners, and we do individual programmes for individual learners but for other learners with similar problems, we use group support. (LST5)

Discussion

This study confirms that learning to read at Grade 3 level is an area of concern. Both the Grade 3 class teachers and LSTs used different methods and modes of working to support learners. The LoLTs in the study were predominately Sepedi and IsiZulu. The scaffolding of the learners in these languages comprised of telling the learners what to do, naming and drilling the words, reading pictures, and reading to the learners. The literature shows that for scaffolding to be effective for learners with reading problems, there has to be a shift in terms of how the teachers provide support to learners. Firstly, the support should allow for collaboration between the teachers and the learners so that the learner can constantly be allowed to check their level of competency (Bekiryazici, 2015:915). Secondly, the support should be structurally presented to allow learners to gradually move from what they cannot do on their own to their next level of independence. Lastly, teachers should ensure that they provide learners with reading tasks that are at an appropriate level within their ZPD (Amerian & Mehri, 2014:760; Bruner, 1983:74; Ismail, Ismail & Aun, 2015:156). Similarly, Vygotsky (1978:127) accentuated that supporting learners in this manner enhanced their higher-order thinking skills, allowed them to learn new cognitive skills, and enabled them to independently learn how to solve problems when confronted with similar challenges in the future. The ultimate goal for scaffolding is, therefore, reaching independence and self-regulation (Ismail et al., 2015:156). This might be challenging for those that experience reading problems, but they should be given opportunities to explore their capabilities.

In this study, the scaffolding was inadequate. The support was presented in a manner that satisfied the teachers' goals. Learners were constrained by the unidirectional support. A one-size-fits-all approach when supporting learners experiencing reading problems was evident although there were some differences. The rates of learning and learning styles were less of a concern although this was evident to some extent in the LSTs' responses.

The mediation in this study showed that a teacher-centred approach was followed in providing reading support and the role of the teacher was to transmit knowledge to the learner. The mediation process started with the teacher choosing the method to use during the support process and the learners imitating the teacher. The process was then followed by the teacher posing closed-ended questions and the learners giving their responses. Finally, the teachers gave feedback on whether the learners answered correctly or not. For mediation to be successful, it should be interactive, allow for dialogue between the teacher, knowledgeable peers, and learners who are being supported (Guerrero Nieto, 2007:217-222). Dialogue for co-construction of meaning was limited for the teachers, as the problem child became the image to guide practice. Using such imagery limits the learners' interaction and participation in the learning process and holds back their creativity and innovation during reading support.

Cultural tools usually define how humans interact and make meaning. To be effective in providing reading support, they should signify the learners' context in the learning environment (Conkbayir & Pascal, 2014:80). In his explanation, Vygotsky (1978:127) emphasised that "like words, tools and nonverbal signs provide learners with the way to become more efficient in their adaptive and problem-solving efforts." In this study, both psychological and physical tools were used, such as flash cards, pictures, and reading books. Teachers used these tools with the specific focus on simplifying the content and helping learners read. The main issue was the relevance of the tools for learners needing specific support. For example, for those experiencing problems with visual perception, spatial problems or information processing, the cultural tools selected on a one-size-fits all approach would be problematic.

As a result, the way in which learner support was given in this study, gives a contextual understanding of where FSS in South Africa feature. In this context, reading problems are addressed in a way where multiple professionals are working on the reading problem even though the systems are not as established like in rich countries.

One of the unique things about South Africa is the number of African languages in which learners in the Foundation Phase need to be taught to read as learners up to Grade 3 are taught in their mother tongue. However, we do not have enough teachers who are professionally prepared to teach reading -particularly in all the home languages (DoE, RSA, 2008:11; Pretorius et al., 2016:2). So the problem does not only lie with poor reading, but also a lack of professional development of teachers to become reading teachers, which is problematic.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore how Grade 3 teachers supported learners who experienced reading problems in FSS. The teachers who participated in this study followed a complex and varied approaches in supporting learners who were experiencing reading problems. A teacher-centred approach was used to achieve learning goals. This limited the use of a co-constructed approach that takes into account the specific barriers to reading and learners' needs. Few attempts were made to actualise prior knowledge through scaffolding. This could be attributed to the nature of the training of Foundation Phase teachers. The short courses offered by the DBE focus on different methods of reading and modes of working but not necessarily the specifics of working with learners who experience particular reading problems. This study amplifies the need for professional development in initial and continued teacher education to include barriers to reading as a core concept to which all Foundation Phase teachers should be exposed. There should be electives to allow for deep specialisations into reading problems. This should be addressed through remedial education courses informed by the latest research on working with reading problems in African languages. This study was a small-scale study and raises ideas for further research on reading problems in African languages.

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge feedback and comments received from Professor HB Ebrahim in the writing of this article.

Notes

i. This article is based on my PhD thesis, "Reading support for Grade 3 learners in full-service schools, Gauteng."

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

iii. DATES: Received: 16 November 2020; Revised: 28 September 2021; Accepted: 1 July 2022; Published: 28 February 2023.

References

Amerian M & Mehri E 2014. Scaffolding in sociocultural theory: Definition, steps, features, conditions, tools, and effective consideration. Scientific Journal of Review, 3(7):756-765. https://doi.org/10.14196/sjr.v3i7.1505 [ Links ]

Azevedo JP, Crawford M, Nayar R, Rogers H, Barron Rodriguez MR, Ding E, Gutierrez Bernal M, Dixon A, Saavedra J & Arias O 2019. Ending learning poverty: What will it take? Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/1ef8a794-710b-584e-a540-a3923ad7ea90/content. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Bandi D 2016. Overview and analysis of SACMEQ IV study results. Available at https://static.pmg.org.za/160913overview.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2017. [ Links ]

Bekiryazici M 2015. Teaching mixed-level classes with a Vygotskian perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186:913-917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.163 [ Links ]

Bertram C & Christiansen I 2016. Understanding research: An introduction to reading research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

Bruner J 1983. Child's talk: Learning to use language. New York, NY: W W Norton. [ Links ]

Carroll J, Bradley L, Crawford H, Hannant P, Johnson H & Thompson A 2017. SEN support: A rapid evidence assessment (Research Report). Coventry, England: Coventry University. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628630/DfE_SEN_Support_REA_Report.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Choate JS (ed.) 2004. Successful inclusive teaching: Proven ways to detect and correct special needs (4th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Conkbayir M & Pascal C 2014. Early childhood theories and contemporary issues: An introduction. London, England: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2010. Introduction to the Gauteng primary literacy strategy. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2017. The SACMEQ IV project in South Africa: A study of the conditions of schooling and the quality of education. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/SACMEQ%20IV%20Project%20in%20South%20Africa%20Report.pdf?ver=2017-09-08-152617-090. Accessed 2 October 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2005. Conceptual and operational guidelines for the implementation of inclusive education: Full-service schools. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.saide.org.za/resources/Library/DoE%20-%20Incl%20Ed%20Guidelines%20Full%20Service%20Schools%20June%202005.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2007. Teaching reading in the early grades: A teacher's handbook. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/CD/GET/doc/PDF%204%20Website.pdf?ver=2007-11-30-122906-000. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2008. National reading strategy. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/DoE%20Branches/GET/GET%20Schools/National_Reading.pdf?ver=2009-09-09-110716-507. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouché CB & Delport CSL (eds.) 2011. Research at grass roots: For the social and human services professions (4th ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Fiester L 2010. Early warning! Why reading by the end of third grade matters. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation. Available at https://www.ccf.ny.gov/files/9013/8262/2751/AECFReporReadingGrade3.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Gillet JW, Temple C, Temple C & Crawford A 2012. Understanding reading problems: Assessment and instruction (8th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Guerrero Nieto CH 2007. Applications of Vygotskyan concept of mediation in SLA. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9:213-228. Available at http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/calj/n9/n9a11.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Hall L 2014. What is a struggling reader? Available at https://leighahall.wordpress.com/2014/05/12/what-is-a-struggling-reader/. Accessed 6 July 2016. [ Links ]

Hammond J (ed.) 2001. Scaffolding: Teaching and learning in language and literacy education. Marrickville, Australia: Primary English Teaching Association. [ Links ]

Howie S, Venter E, Van Staden S, Zimmerman L, Long C, Du Toit C, Scherman V & Archer E 2008. PIRLS 2006 summary report: South African children's reading literacy achievement. Pretoria, South Africa: Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, University of Pretoria. Available at https://nicspaull.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/howie-et-al-pirls-2006-sa-summary-report.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Howie SJ, Combrinck C, Roux K, Tshele M, Mokoena GM & McLeod Palane N 2017. PIRLS literacy 2016: South African highlights report. Pretoria, South Africa: Centre for Evaluation and Assessment. Available at http://www.shineliteracy.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/pirls-literacy-2016-hl-report.zp136320.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Hugo A & Lenyai E (eds.) 2013. Teaching English as a first additional language in the foundation phase: Practical guidelines. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Ismail N, Ismail K & Aun NSM 2015. The role of scaffolding in problem solving skills among children. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 85:154-158. [ Links ]

Jackson A & Kiersz A 2016. The latest ranking of top countries in math, reading, and science is out - and the US didn't crack the top 10. Business Insider India, 7 December. Available at https://www.businessinsider.in/the-latest-ranking-of-top-countries-in-math-reading-and-science-is-out-and-the-us-didnt-crack-the-top-10/articleshow/55843743.cms. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Joubert I, Bester M & Meyer E 2008. Literacy in the foundation phase. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Joubert I (ed.), Bester M, Meyer E & Evans R 2013. Literacy in the foundation phase (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Karami H 2008. Reading strategies: What are they? Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED502937.pdf. Accessed 2 October 2020. [ Links ]

Lawrence JW 2011. The approaches that Foundation Phase Grade 3 teachers use to promote effective literacy teaching: A case study. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43167752.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

Le Cordeur M 2010. The struggling reader: Identifying and addressing reading problems successfully at an early stage: Language learning notes. Per Linguam: A Journal of Language Learning, 26(2):77-89. https://doi.org/10.5785/26-2-23 [ Links ]

Lee GL, Gable R & Klassen VK 2012. Effective reading remediation instructional strategies for struggling early readers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46:822-827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.206 [ Links ]

Martin MO, Mullis IVS & Foy P 2016. Assessment design for PIRLS, PIRLS literacy, and ePIRLS in 2016. In IVS Mullis & MO Martin (eds). PIRLS 2016 assessment framework (2nd ed). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). Available at https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/downloads/P16_Framework_2ndEd.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

McKinley J 2015. Critical argument and writer identity: Social constructivism as a theoretical framework for EFL academic writing. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 12(3):184-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2015.1060558 [ Links ]

Mule K 2014. Types and causes of reading difficulties affecting the reading of English language: A case of Grade 4 learners in selected schools in Ogong circuit of Namibia. MEd thesis. Windhoek, Namibia: University of Namibia. Available at https://repository.unam.edu.na/bitstream/handle/11070/851/Mule2014.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 28 February 2023. [ Links ]

National Center for Education Statistics 2017. National assessment of educational progress: An overview of NAEP. [ Links ]

Paratore JR & Dougherty S 2011. Home differences and reading difficulty. In A McGill-Franzen & RL Allington (eds). Handbook of reading disability research. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Place J 2016. Teaching reading and viewing. In A Hugo (ed). Teaching English as a first additional language in the intermediate and senior phase. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Pretorius E, Jackson MJ, McKay V, Murray S & Spaull N 2016. Teaching reading (and writing) in the foundation phase: A concept note. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Research on Socio-Economic Policy, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Spaull N, Van der Berg S, Wills G, Gustafsson M & Kotzé J 2016. Laying firm foundations: Getting reading right. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch. Available at http://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ZENEX_LFF-email.pdf. Accessed 6 April 2017. [ Links ]

Spear-Swerling L 2016. Common types of reading problems and how to help children who have them. The Reading Teacher, 69(5):513-522. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1410 [ Links ]

Townend J & Turner M (eds.) 2000. Dyslexia in practice: A guide for teachers. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [ Links ]

Vacca JAL, Vacca RT, Gove MK, Burkey LC, Lenhart LA & McKeon CA 2011. Reading and learning to read (8th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Verenikina I 2008. Scaffolding and learning: Its role in nurturing new learners. In P Kell, W Vialle, D Konza & G Vogl (eds). Learning and the learner: Exploring learning for new times. Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong. [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1997. The collected works of LS Vygotsky (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Wertsch JV 2002. Computer mediation, PBL, and dialogicality. Distance Education, 23(1):105-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910220124008 [ Links ]