Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 n.4 Pretoria Nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n4a2138

School leadership practice at faith-based schools through a servant leadership lens

Melese ShulaI; Chris van WykI;Jan HeystekII

Edu-Lead Research entity, Faculty of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Edu-Lead Research entity, Faculty of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa jan.heystek@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article we report on an investigation into developing people and serving the community at faith-based schools through a servant leadership theory lens. Relevant literature was reviewed, and data were collected from school leaders by means of individual semi-structured interviews. Twelve participants were purposively selected from schools classified as top-performing schools in Gauteng, a province in South Africa. The interviews with these participants were audiotaped and transcribed, and the data analysed by using a process of abductive data analysis. The following measures were employed to review the servant leadership practices of faith-based leaders: being a serving leader, fostering people growth, and enhancing community relationships. Overall, principals were found to be effective leaders involved in a hands-on manner in both task-orientated and person-orientated activities. The servant leadership conception whereby "other" interests are regarded as more important than own interests serves as the basis for people development and there is a clear awareness that the enhancement of community relationships is a key facet in the communication that takes place between school principals and community members. The participants also showed concern for school-led development activities. It was evident that participating school staff were personally involved in facilitating learning activities such as collaborative workgroups and workshops and in creating a supporting structure for staff development. Apart from recommending that principals' leadership behaviour in the abovementioned areas is consolidated, we strongly support their involvement in related matters such as coping with contextual realities and enhancing community relationships. The improvement of community relationships is eventually a challenging task to be exercised by principals within the social, political and demographic contexts of faith-based schools.

Keywords: community service; contextual factors; developing people; faith-based schools; leadership practices; leadership style; leadership theories; servant leadership

Introduction

Most current expositions on the phenomenon of leadership originated in the latter part of the previous century (Greenfield, 1975; Halpin, 1966). The concept of leadership suggests a kind of behaviour undertaken by a person or persons with the idea of getting others to follow suit (Gray, 2012:102). These actions are usually defined as guiding and influencing others in a particular direction (Christie, 2010:695) or, as T Taylor, Martin, Hutchinson and Jinks (2007:404) aptly put it, "leadership is a process involving fusing thought, feeling and action to produce a cooperative effort that serves the values and purposes of both the leaders and the led."

Our study was conducted using a servant leadership theory lens. With this approach, we attempted to highlight the significance of leadership behaviour in an educational context by focusing on the principal's role in developing people and serving the community. The main focus was on faith-based schools, which, at face value have a unique character in the sense that they are mainly Christian schools that attempt to offer "citizens freedom to practise the education of their choice, thus allowing for the diversity desired in the new South Africa" (Hofmeyer & Lee, 2002:78). In light of Christian schools' apparent prescriptive value systems and concomitant limitation on choices, this assertion might sound contradictory or even ambiguous but the opposite applied in this study. In fact, we aligned ourselves with the thinking of Franco and Antunes (2020:346) who pronounced that "[s]ervant-leadership provides a conceptual structure for the new dynamics now required for leadership."

The study is significant in and for the South African context since there are many studies, which assessed and subsequently described and explained leadership practice using a servant leadership lens in a number of countries (Dulewicz & Higgs, 2005; Miller, 2018). Concerning investigations in leadership at faith-based schools in particular, the picture is, however, completely different. We could not establish any research studies with this angle of investigation.

Problem Statement

The first clearly delineated leadership approaches in the field of educational leadership are person-centred and based on the assumption that leaders are naturally exceptional in their mental and physical abilities (Smith, Montagno & Kuzmenko, 2004:81).

This kind of focus represents idealistic views about the characteristics of "great" leaders without taking into account their often-imperfect personalities (Gray, 2012:102). Subsequent research portrays a range of different perspectives. According to Hoyle (1986:106), Halpin's (1966) ideas about initiating structure and consideration are key elements in understanding the nature and functioning of educational leadership. Initiating structure means providing positive leadership as well as consistency and direction and should not be confused with autocratic leadership (Van der Westhuizen, 2015:72). Consideration, in turn, deals with the nature of the relationship between a leader and his or her followers reflecting mutual respect and trust as important dimensions (Leithwood, Harris & Hopkins, 2008:29). Gray (2012:100) further contends that it is academically irresponsible not to include context as a critical component in leadership theory. In our investigation, we thus regarded context as crucial because it emphasises that school leaders should match the style and situational factors in their practice.

Further advances in leadership research indicate a paradigm shift from traditional functionalism and behaviourism to subjective and practice-based approaches. Relevant for this study was the focus on leaders' involvement in community matters as an integral part of current school practice (Hallinger, 2019:555). Boak and Crabbe (2019:98) add developing leadership capacity and redesigning the school organisation structure as important current day activities, while Mestry (2017:7) views the promotion of a culture of professional development as a critical component of school leaders' involvement in capacity building.

In formulating our research problem, we noted the above-mentioned perspectives and opted for servant leadership theory as a plausible avenue for investigating the leadership practices at faith-based schools. This view was strengthened by taking cognisance of the fact that the landscape of studies on servant leadership has increased remarkably during the last 5 to 10 years (Gandolfi, Stone & Deno, 2017:352). Bush and Glover (2014) and Gumus, Bellibas, Esen and Gumus (2018) associate servant leadership with related theories such as moral leadership and transformational leadership, critically focusing on the values, beliefs and ethics of leaders.

Within this focus, we concentrated explicitly on leadership in faith-based schools, a research area that has not received meaningful attention from school leadership experts and scholars in the past. We are in agreement with Grace (2003:150) who remarks that "a comprehensive construct of educational inquiry must include engagement with specific faith cultures in given educational situations." Apart from having the potential of making a noteworthy contribution to current knowledge on leadership in faith-based schools specifically, and on servant leadership practices in schools in general, the rationale for the study on which this article is based, was to investigate the role of principals in developing people and in serving their communities.

The specific research problem was consequently formulated as follows: What is the role of the principal in developing people and serving the community at faith-based schools?

In order to expand the extant body of knowledge on leadership at faith-based schools, the servant leadership practices of principals and teachers were examined at such schools in South Africa. To prepare for this investigation, we first developed a conceptual and theoretical framework regarding faith-based leadership, which is expanded on in the next section. This is followed by sections containing an outline of the empirical investigation, the findings flowing from it, a discussion of the findings, and a conclusion.

Conceptual-theoretical Framework This section was structured to highlight the key tenets of school leadership that lead to the identification of criteria that served as a lens for viewing the leadership practices of principals at faith-based schools. We noted that successful school leadership has been linked with practical ideas on principals' involvement in people development and leadership in community matters (Hallinger, 2019:555). The importance of situational or contextual factors is also regarded as an integral part of this investigation. School leaders blend and eventually navigate organisational and contextual factors to establish successful school leadership practice (Miller, 2018:171).

Leadership in faith-based schools

Faith-based schools are unique because of the ways in which they are related to and influenced by the purposes, characteristics and ethos of the particular faith of a school, and by its religious traditions (McLaughlin, 2005:223). Faith-based schools also possess a "dual identity" and "dual missions" (Grace, 2009:491). This dual character is an upshot of the competitive market and accountability forces created by government policies, and of the reforms and influences from the religious communities that oversee the schools (McGettrick, 2005:106).

In South Africa, faith-based schools represent a wide range of religions and faiths but are predominantly Christian in affiliation (Motala & Dieltiens, 2008:130). These schools function under the auspices of either the Association of Christian Schools International (ACSI), the Catholic Institute of Education (CIE) or the Independent Schools Association of Southern Africa (ISASA). According to Hofmeyer and Lee (2002:78), the post-1994 educational policy context is generally supportive of faith-based schools and recognises "the argument that independent schooling offers citizens freedom to practise the education of their choice, thus allowing for the diversity desired in the new South Africa." The racial profile of post-apartheid independent schools has changed dramatically since 1994. Hofmeyer and Lee (2002:79) report that the "majority of learners at these schools are now Black, while the majority of schools are new (established since 1990), charge average to low fees and are religious or community-based." Furthermore, the number of learners attending independent schools in South Africa doubled within the first 10 years after 1994 (Motala & Dieltiens, 2008). The integrity of faith-based school leaders is of paramount importance. According to Kouzes and Posner (2006:88), "if people do not believe in a leader, they will not believe the leader's message." Brown (2007:89) argues that to be believed, leaders at these schools have to personify the life they advocate. They must act consistently with their beliefs (Hall, 2014:70). Faith-based Christian school leaders are, for example, first believed to be followers of Christ before being leaders. Hall (2014:68) notably emphasises that a Christian school leader need not be living a perfect life, but it does need to be a life of integrity. Edwards (2014:56) points out that such school leaders are expected to combine the professional and spiritual aspects of their lives as they serve the school community. Striepe, Clarke and O'Donoghue (2014:94) add that the practices of leaders are value-driven. Their perspectives on leadership, however, are shaped by their own philosophy and spirituality and enhanced by that of the affiliated faith of the school. School leaders' beliefs indeed shape their vision, their relationships and the manner in which they lead. As Hulst (2012:67) says, "faith-based Christian school leaders should in particular endeavour to be servant-hearted people, who lead as people who serve God and the community and who give of themselves, demonstrating passion for their cause." In order for these leaders to be effective, they have to lead by example and communicate clearly how the particular beliefs affect schooling (Hulst, 2012:46).

The insights obtained in this part of the literature review illustrated the unique character of faith-based schools and emphasised the servant orientation of their leaders. The exposition also served as the basis for the investigation regarding servant leadership theory.

Servant leadership theory

Although the idea of servant leadership can be traced back to early times, it is still seen by many as a fairly new term and "is often confused with only acts of service, or leadership that only serves, when in fact, this leadership style is more" (Drury, 2005:10). Gandolfi et al. (2017:351) indicate that a variety of world cultures have been practising servant leadership ideas. According to Sendjaya and Sarros (2002:58), however, one of the best recorded examples of servant leadership in history comes from the teachings of Jesus Christ who was the first to "introduce the notion of servant leadership to everyday human endeavour." Gandolfi et al. (2017:351) further remark that "these teachings were paradoxical two thousand years ago, and still present a conundrum today." These perceived contradictions and misunderstandings form part of the discussion in the next part of this section, which deals more directly with servant leadership practices.

Greenleaf's (1977) pronouncement of servant leadership as a distinguishable leadership theory was followed by a number of dissenting and assenting voices. Sergiovanni (1990:48) regards servant leadership as a fairly novel but realistic theory among various leadership theories, whereas Franco and Antunes (2020:345-346) view it as part of a new paradigm, emphasising "the moral, emotional and relational dimensions of leadership behaviour." Shula (2019:23) additionally points to the differences and parallels between servant leadership and theories such as moral leadership, ethical leadership and transformational leadership. We limit our comments in this part of the article to differences and similarities between servant leadership and just one other theory, namely transformational leadership, because the latter "has gained the greatest momentum in the field of leadership studies" (Copeland, 2014:106) and is similar to servant leadership, focusing on people as the important aspect in the organisation.

According to Bass (2000:23), a comparison between these two theories shows that they are "comparable and complementary in terms of the growth of followers through personalised considerations, intellectual incentives and reassuring behaviours." It is, however, also apparent that the core focus of transformational leadership is to change and improve the organisation while the commitment of a servant leader lies with "the psychological needs of followers as a goal in itself" (Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014:148). Despite differences between the two theories mentioned, both can be characterised as theories with a value foundation (Gandolfi & Stone, 2018:265; Middlehurst, 2008; Steyn, 2012:48), which are directly opposed to rationalistic perspectives that form part of the traditional hierarchic and bureaucratic approach (Taylor, T et al., 2007:406). C Taylor (2004:210) regards value-based theories as those that inspire "value-driven leaders who tend to relationships" and signify an "important source of hope and courage." Bush and Glover (2014:555) explain that these leaders are "expected to ground their actions in clear personal and professional values."

Our understanding of servant leaders' practices was guided by Greenleaf's (1977, 1996) explications of servant leadership attributes and by resulting discussions by various authors such as Blanchard (2002:x), Covey (2002:30), Fullan (2014:48), Sergiovanni (2005:44) and Spears and Lawrence (2004:49). The elucidation of Copeland's (2014:105) perspective, which emphasises the importance of concentrating on related leadership constructs such as moral, ethical and transformational leadership, was also of critical importance. The views of Eva, Robin, Sendjaya, Van Dierendonck and Liden (2019) were further considered for purposes of formulating key servant leadership criteria, as explained below. In combination, these criteria served as a lens for the discussion of leadership practices at faith-based schools. From the above, the following criteria were selected based on the importance for servant leadership and were used for the analysis of principals in faith-based schools as servant leaders.

Criterion 1: Being a serving leader

Eva et al. (2019:114) propose that the apparent contradiction of a leader as a servant should in fact be seen as a "juxtaposition of apparent opposites where the leader exists to serve those whom he or she leads." In order to be a servant leader, one has to be prepared to be a leader first (Taylor, T et al., 2007:405). Being a servant leader reflects both the actions of a servant who leads and of a leader who serves. Franco and Antunes (2020:351) further emphasise that servant leadership is based on the overarching action of caring for others, while Eva et al. (2019:114) see this dimension as an "other-oriented approach to leadership." This criterion embodies the notion that servant leaders answer the call to serve, and focus selflessly on the interests of others before self-interest or organisational interest.

Criterion 2: Fostering people growth

Although different kinds of leadership development can be accommodated in servant leadership, Greenleaf (1977:13-14) conceptualises the vital aspects of this criterion by asking, "Do those served grow as persons; do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?" Fostering growth by attending to these thought-provoking questions implies that others are consistently empowered while their well-being is promoted. T Taylor et al. (2007:404) regard such a perspective as "a new leadership approach [that] attempts to enhance the personal growth of workers and improve the quality of the organization through a combination of teamwork, shared decision-making and caring behaviour."

Criterion 3: Enhancing community relationships

Enhancing school-community relationships is evidently a criterion for effective school leadership (Valli, Stefanski & Jacobson, 2018:32). Eva et al. (2019:114) highlight the reciprocal nature of the relationship between a servant leader and the school community, also emphasised by Wolhuter, Van der Walt and Steyn (2015:3) as follows: "there are continuity and reciprocity between individuals and their contexts." This focus is in line with our research problem emphasising both the influence of situational factors on leadership practice and the influence servant leaders have on the school community. Within this ambit of concern for others, servant leaders have a critical responsibility for developing the school community and building a caring relationship with all school stakeholders.

In sum, the criteria that we applied in the process of discussing the successfulness of leaders at faith-based schools were those of being a serving leader, fostering people growth, and enhancing community relationships.

Research Design and Methodology

We employed a qualitative case study design (Rule & John, 2011:89) in the study reported on here. This design afforded us the opportunity to obtain in-depth information about the school lives of selected participants at faith-based schools in South Africa who function under the auspices of three umbrella bodies (ACSI, CIE and ISASA). Twelve participants were purposively selected from schools classified as top-performing schools in Gauteng (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2016). By means of telephonic conversations with head office staff we were informed that all principals and senior teachers who come under their auspices, received advanced training, which included training in servant leadership practices. We thus selected nine principals and three teachers based on geographical location in Gauteng. Individual interviews were held in a central location after school hours with these principals and teachers.

Interview schedules and tentative questions that were part of the research ethics clearance obtained from the University of South Africa (Unisa) were discussed at a combined meeting with all the participants. The purpose of the meeting was to gain a general understanding of the contexts of the schools and to explain to the participants what the study entailed. Based on the input obtained from the participants, we changed the wording of some questions. Assurance of confidentiality was conveyed at this meeting, and participants' consent was obtained. Observation notes that were made during and directly after the meetings were aligned with the format of the interview schedule and recorded in a separate column to form part of the transcribed interviews.

The individual interviews lasted about an hour per individual, and provided sufficient in-depth data. We used the principles of member checking to solicit feedback on the accuracy of transcriptions from the interviewees by email. A focus-group discussion was subsequently held to stimulate interaction between the group of participants with the idea to achieve depth in exploration of several critical answers identified during the individual interviews (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010:377). Pseudonyms were used for participants, namely Mancho, Beto, Birke, Shole, Wollima, Fulasa, Kakawo, Shiminta, Muni, Mededo, Bunaro and Basho.

We followed an abductive data analysis approach that combined inductive and deductive approaches (Bickmore & Bickmore, 2010:1009). As suggested by McMillan and Schumacher (2010:369), predetermined themes that were embedded in the research question were first selected to serve as initial directives "for what you look for in the data" (Maree, 2007:109). Segments of the data were then colour-coded and assigned to these predetermined themes. Next, the transcripts were re-read and the interview data analysed inductively. The idea was that each code had to indicate a challenge or action or another piece of relevant information that pertained to servant leadership in faith-based schools. The essence of the codes was then captured by putting similar codes together as themes. In combining the two sets of themes, we followed the process of recursive analysis (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010:377) in which categories or themes were combined by constantly searching for both supporting and contrary evidence about the essence of existing themes. After the focus-group interviews, the underlying three themes that displayed the perspectives of faith-based school leaders in their leadership practice were finalised. The explication of each theme followed the pattern of developing descriptions, using wording from the participants and "describing how the narrative outcome will be compared with theories and the general literature" (Creswell, 2009:194). We conclude the discussion of each of the themes with an evaluation based on the criteria defined in the section on servant leadership theory above.

Findings

In this section, we provide an overview of the findings, which emanated from the interviews and focus-group discussion and related to the role of school principals in developing people and serving communities through servant leadership practices in faith-based schools as described. Each finding culminates in a discussion that, among others, links the insights of international authors to the different criteria. In this way, the initial findings that pertain to a specific South African context become part of a wider discourse centring on criteria that could be employed internationally as well.

Leaders Acting as Servants

Participants were of the view that leaders of faith-based schools demonstrate servant leadership ideals such as being unselfish and having the ability to establish positive human relationships with staff and learners alike. Beto emphasised, "we are leaders of Christian schools. As such, we are called to serve others before ourselves." This "call to serve" at faith-based schools was clearly understood as pastoral care in which learners' emotional and scholastic development were addressed. Participants Wollima and Shiminta confirmed that, apart from academic performance, a sense of self-confidence, interpersonal skills, self-esteem and personal faith needs to be instilled in learners. During the focus group discussion, principals additionally indicated that they were comfortable with being regarded as servants who were answerable for staff and learners' academic, personal, spiritual and emotional needs. Shiminta commented, "social upliftment is one of the core components of Christian beliefs and part of the catholic ethos." Wollima stated that "[t]he vision of our school is created with the contribution of every staff member'" Shole referred to learners' academic, spiritual, intellectual, psychological and emotional needs as key aspects of the vision.

Wallace (2000:198) is of the view that "faith-based Christian school leaders who are servant-leaders are expected to be visionaries." According to Greenleaf (1977:22), a vision is created through foresight and conceptualisation, which means that "the servant-leader needs to have a sense for the unknowable and be able to foresee the unforeseeable which is to come." Hoyle (1986:111) regards this kind of visioning as a concern "with the transcendental character of a religion" whereas Banke, Maldonado and Lacey (2012:255) argue that Christian school leaders must also fully understand the responsibility of promoting academic excellence in a Christian school. In drawing on research conducted in four countries, Grace (2003:155) emphasises in this regard that faith-based school principals' "execution of their leadership role is so exemplary that learners achieve better scholastically than their counterparts at public schools."

In terms of the first criterion, being a serving leader, it was evident that leaders were committed practitioners who consistently put the interests of their staff above own interest. What stood out was the visionary way in which participating principals were involved in social upliftment. Mededo said in this connection, "faith-based Christian schools are called to social justice. So, that means getting up there and making it better for the disadvantaged in our South Africa. "

Staff Development as Leadership Task

Staff growth featured prominently in the interviews as a key task of faith-based school principals. As stated during the interviews, true staff development is only possible when teachers are valued as professionals. Birke expanded on this, saying, "[a]t our school we are always looking at opportunities to enhance the intellectual and professional capacity of the staff and improve their working conditions." Wollima reiterated, "we have to affirm staff... tell them they are doing a good job ... say we value you as a staff member." Shiminta, Fulasa and Mededo further referred to the emotional well-being of staff members, saying that staff empowerment actions such as shared decision-making and teamwork facilitation form an integral part of school life. The shared perspective of teamwork facilitation was highlighted by various participants. Bunaro's view was that "the most important management principle that I think about is teamwork and being part of a team. " Shole regarded the functioning of teams as "shared decision-making", and Wollima emphasised, "you need a real team approach from everybody."

The essence of this theme is mirrored by Duignan (2012:119) who emphasises that effective leaders should always be facilitating teachers' professional development and that "capacity is built through empowering, affirming, inspiring, supporting, and entrusting others." Steyn (2012:47) confirms the view that a leader's effectiveness is visible when other staff members are supported, by displaying

• respect for human dignity;

• promotion of collaborative decision-making;

• feelings of trust;

• job satisfaction; and

• commitment to organisational goals.

The criterion, fostering people growth, was applied in this theme. The participating principals showed empathy and concern for teachers and supported school-led development activities. Their success was evident from their personal involvement in facilitating learning activities such as collaborative workgroups and workshops and in creating a supporting structure for staff development.

It was, however, further established that schools in general and not only the schools under study should focus on external development opportunities such as university courses and departmental leadership activities. These external activities should include leadership programmes such as the new Advanced Diploma in Education (School Leadership and Management) proposed by Bush and Glover (2016:211-231).

School-community Relationships as Leadership Task

Good school community relationships are imperative for the effective functioning of schools and school leaders. All interviewees indicated that they were constantly aware of the challenging context in which they were working at the time. As demonstrated it was evident that the school community had a critical influence on the functioning of the school and on the behaviour of school leaders. In particular, Bunaro and Shiminta affirmed that the demographics of faith-based schools had greatly changed since 1994, with the result that the majority of current learners came from impoverished backgrounds. Basho said that this had made the internal and external context of faith-based schools more complex during the last 25 years. Mededo and Birke indicated that school leaders adapted their role as serving and caring for staff and learners "to the broader school community, including caring for parents as well as for the school's neighbourhood, and society at large." Muni's comments in this regard were pertinent: "[a]s a leader of a faith-based Christian school, I'm adamant that our schools should be reflective of society."

The value and importance of context at faith-based schools that were mentioned during the interviews, are also highlighted by various authors (cf. Eva et al., 2019; Miller, 2018; Taylor, T et al., 2007). According to Hallinger (2019:543) and Wolhuter et al. (2016:3-4), a school context can be seen as consisting of an internal and a community context. This view allowed us to outline internal context and community context as two dimensions pertinent to the functioning of faith-based leadership in schools. The internal or leader-specific context comprises the leader's own situation, including experience, knowledge and behaviour, as well as the school setting within which the leader operates, comprising learner composition, staff circumstances and organisational matters. Community context encompasses the influence of local environmental issues on school leadership such as safety and security and the living conditions of community members.

The situation described above is also seen in the South African context, where internal and community factors in the context of a school serve as co-determinants for the effectiveness of the leadership practice of such school. The current demographics of South African faith-based schools in particular present serious leadership as well as community relationships challenges to these schools and their leadership.

With regard to the criterion, enhancing community relationships, it was evident that the effectiveness of school leaders depends on the reciprocal relationship between such leaders and the school community. On the one hand, faith-based leaders' active involvement in community matters qualifies them as exemplary servant leaders. On the other hand, these leaders understand the context within which they work, and they show care for the community through their involvement in developmental issues. This kind of involvement and community support are obviously key components of effective community relationships.

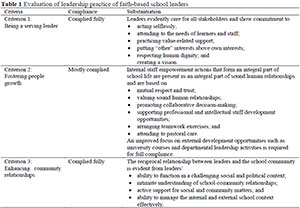

Table 1 below presents a summative review of the practices of leaders of faith-based schools. Compliance is appraised at three levels, namely complied fully, mostly complied, and no compliance. Substantiation for the evaluation of leadership behaviour per degree of compliance is included in the third column.

Discussion

The exposition in this discussion was mainly constructed by scrutinising related theoretical viewpoints and data from the interviews regarding the research problem: What is the role of the principal in serving the community and developing people at faith-based schools?

We found a close relation between theoretical conceptions of servant leadership and being leaders at faith-based schools. It was indicated clearly that principals of these schools were mindful of how applicable servant leadership tenets were included in their practice. There was a clear awareness and acceptance by principals of the practicality of "being called to serve" and how the task of leading and managing is intertwined with serving. During the interview stage of this investigation, a principal-participant was quoted as saying "we are leaders of Christian schools. As such, we are called to serve others before ourselves" In the case of faith-based schools as portrayed it is, therefore, clearly expected of principals to be servants first (Greenleaf, 1977:8) who consistently put the interests of others above own interests. Principals thus find themselves in a somewhat paradoxical position whereby they have to exercise their influence as leaders but concurrently follow a serving approach.

In the case of principals at faith-based schools, the process of serving while exerting influence applies in particular to the school community consisting of internal school members, the external community and the wider community. Enhancing community relationships is a key facet of the communication that takes place between school principals and community members. In terms of the servant-leadership paradigm, the leadership that principals provide is not only part of effective organisation and administration but also important in enhancing community relationships. In order to lead actively and improve community relationships, principals must show an intimate understanding of how these relationships function within a faith-based school setup. The demographic location of schools, schools' affiliation and the transcendental character of the Christian religion also affect relationships with different community members considerably. The improvement of community relationships is eventually a challenging task to be exercised by principals within the social, political and demographic context of faith-based schools.

We indicated previously that people development is based on mutual respect and trust and that sound human relationships and material support are key mechanisms in successful development. Respect for human dignity and commitment to school goals are also identified by authors such as Duignan (2012:119) and Steyn (2012:47) as being closely connected to the principal's task of developing effective people. These and much older theoretical deliberations (cf. Hoyle, 1986:106) further show human-related aspects such as consideration and respect as important components in people development (in this case, staff development). We argue, however, that servant leadership theory with its strong subjective base and value orientation is more relevant than traditional power-based theories to explain and lead people development initiatives in schools. The foundation of servant leadership where "other" interests are regarded as more important than own interests can be used to great effect as basis for people development.

We further found that, unlike traditional kinds of people development done in a top-down and prescriptive fashion, faith-based principals executed development where aspects such as human dignity and vision-creation were recognised as key facets. It was shown that the nurturing and fostering of self-awareness while empowering people was part and parcel of development activities of school principals. The findings additionally reflect that development actions in faith-based schools are based on the morals and values of Christianity.

Conclusion

Participating principals reflected on their own practices and strongly indicated that their first priority was to serve, which is the most important component for servant leadership. Although other leadership types may also have service as criterion, the essence of servant leadership is not the leader but the service and the community and to improve the other. Leadership in faith-based schools is clearly regarded as a multi-faceted and multi-functional activity and principals are required to perform a wide range of leadership tasks that are linked to influencing staff and learner matters while acting as serving leaders. This is similar to any other school but the focus on service and being in the service of others dominates this specific approach to leadership.

Caring for and serving other people are key actions performed by principals in faith-based schools. This servant approach served as basis for explaining the role of the principal in developing people and serving the community at faith-based schools. Staff development and getting the community involved are crucial aspects for the success of academic achievement at schools. In this research we found that servant leadership is a priority and may serve as an indication that principals who want to improve the quality of education at schools should emphasise the servant approach. More research is needed to establish the link between servant leadership and the quality of education to emphasise the importance of servant leadership and service as a strong possibility to improve schools.

Authors' Contributions

Dr Shula - Data from the thesis; data collection and writing of the first and improvement drafts. Prof. Van Wyk - Study leader; conceptualisation of article with Dr Shula. Assisted in the improvement of the drafts. Prof. Heystek - Conceptualisation and improvement of drafts and finalisation of article.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Banke S, Maldonado N & Lacey CH 2012. Christian school leaders and spirituality. Journal of Research on Christian Education, 21(3):235-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10656219.2012.732806 [ Links ]

Bass BM 2000. The future of leadership in learning organizations. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 7(3):18-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190000700302 [ Links ]

Bickmore DL & Bickmore ST 2010. A multifaceted approach to teacher induction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4):1006-1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.043 [ Links ]

Blanchard K 2002. Foreword: The heart of servant-leadership. In LC Spears & M Lawrence (eds). Focus on leadership: Servant-leadership for the 21st century. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Boak G & Crabbe S 2019. Experiences that develop leadership capabilities. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(1):97-106. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0254 [ Links ]

Brown G 2007. Weighing leadership models: Biblical foundations for educational leadership. In JL Drexler (ed). Schools as communities: Educational leadership, relationships, and the eternal value of Christian schooling. Colorado Springs, CO: Purposeful Design. [ Links ]

Bush T & Glover D 2014. School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership & Management, 34(5):553-571. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2014.928680 [ Links ]

Bush T & Glover D 2016. School leadership and management in South Africa: Findings from a systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(2):211-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2014-0101 [ Links ]

Christie P 2010. Landscapes of leadership in South African schools: Mapping the changes. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(6):694-711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210379062 [ Links ]

Copeland MK 2014. The emerging significance of values based leadership: A literature review. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(2):105-135. Available at https://fisherpub.sjf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=business_facpub. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Covey SR 2002. Servant-leadership and community leadership in the twenty-first century. In LC Spears & M Lawrence (eds). Focus on leadership: Servant-leadership for the 21st century. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2016. National Senior Certificate Examinations 2016: A system on the rise! Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/NationalSeniorCertificate(NSC)Examinations/2016NSCExamReports.aspx. Accessed 23 September 2018. [ Links ]

Drury S 2005. Teachers as servant leaders: A faculty model for effectiveness with students. In Proceedings of the servant leadership roundtable. Virginia Beach, VA: School of Leadership Studies, Regent University. Available at http://www.drurywriting.com/sharon/drury_teacher_servant.pdf. Accessed 21 February 2020. [ Links ]

Duignan P 2012. Educational leadership: Together creating ethical learning environments (2nd ed). Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dulewicz V & Higgs M 2005. Assessing leadership styles and organisational context. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2):105-123. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940510579759 [ Links ]

Edwards R 2014. Leadership. In K Goodlet & J Collier (eds). Teaching well: Insights for educators in Christian schools. Canberra, Australia: Barton Books. [ Links ]

Eva N, Robin M, Sendjaya S, Van Dierendonck D & Liden RC 2019. Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly Journal, 30(1): 111-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004 [ Links ]

Franco M & Antunes A 2020. Understanding servant leadership dimensions: Theoretical and empirical extensions in the Portuguese context. Nankai Business Review International, 11(3):345-369. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-08-2019-0038 [ Links ]

Fullan M 2014. The principal: Three keys to maximizing impact. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Gandolfi F & Stone S 2018. Leadership, leadership styles, and servant leadership. Journal of Management Research, 18(4):261 -269. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Franco-Gandolfi/publication/340940468_Leadership_Leadership_Styles_and_Servant_Leadership/links/ 5ea6a029a6fdccd79457ffa9/Leadership-Leadership-Styles-and-Servant-Leadership.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Gandolfi F, Stone S & Deno F 2017. Servant leadership: An ancient style with 21st century relevance. Review of International Comparative Management, 18(4):350-361. [ Links ]

Grace G 2003. Educational studies and faith-based schooling: Moving from prejudice to evidence-based argument. British Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2):149-167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00231 [ Links ]

Grace G 2009. Faith school leadership: A neglected sector of in-service education in the United Kingdom. Professional Development in Education, 35(3):485-494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580802532662 [ Links ]

Gray HL 2012. Leadership - an elusive concept. International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 8(2):99-106. https://doi.org/10.1108/17479881211260472 [ Links ]

Greenfield TB 1975. Theory about organisations: A new perspective and its implications for schools. In M Hughes (ed). Administering education: International challenges. London, England: Athlone Press. [ Links ]

Greenleaf RK 1977. Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Greenleaf RK 1996. On becoming a servant-leader. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Gumus S, Bellibaş MS, Esen M & Gumus E 2018. A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1):25-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216659296 [ Links ]

Hall J 2014. The life of the leader. In JL Drexler (ed). Schools as communities: Educational leadership, relationships, and the eternal value of Christian schooling. Colorado Springs, CO: Purposeful Design. [ Links ]

Hallinger P 2019. Science mapping the knowledge base on educational leadership and management in Africa, 1960-2018. School Leadership & Management, 39(5):537-560. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1545117 [ Links ]

Halpin AW 1966. Theory and research in administration. New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hofmeyer J & Lee S 2002. Demand for private education in South Africa: Schooling and higher education: The private higher education landscape: Developing conceptual and empirical analysis. Perspectives in Education, 20(4):77-85. [ Links ]

Hoyle E 1986. The politics of school management. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton. [ Links ]

Hulst JB 2012. Christian education: Issues of the day. Sioux Center, IA: Dordt Press. [ Links ]

Kouzes JM & Posner BZ 2006. A leader's legacy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Leithwood K, Harris A & Hopkins D 2008. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1):27-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800060 [ Links ]

Maree K (ed.) 2007. First steps in research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

McGettrick B 2005. Perceptions and practices of Christian schools. In R Gardner, J Cairns & D Lawton (eds). Faith schools: Consensus or conflict? London, England: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

McLaughlin D 2005. The dialectic of Australian Catholic education. International Journal of Children's Spirituality, 10(2):215-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13644360500154342 [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S 2010. Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Mestry R 2017. Empowering principals to lead and manage public schools effectively in the 21st century. South African Journal of Education, 37(1):Art. #1334, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n1a1334 [ Links ]

Middlehurst R 2008. Not enough science or not enough learning? Exploring the gaps between leadership theory and practice. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4):332-339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00397.x [ Links ]

Miller PW 2018. The nature of school leadership: Global practice perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70105-9 [ Links ]

Motala S & Dieltiens V 2008. Caught in ideological crossfire: Private schooling in South Africa. Southern African Review of Education, 14(3): 122-136. [ Links ]

Rule P & John V 2011. Your guide to case study research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Sendjaya S & Sarros JC 2002. Servant leadership: Its origin, development, and application in organizations. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(2):57-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900205 [ Links ]

Sergiovanni TJ 1990. Value-added leadership: How to get extraordinary performance in schools. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [ Links ]

Sergiovanni TJ 2005. Strengthening the heartbeat: Leading and learning together in schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Shula MT 2019. Servant-leadership practices of school principals in faith-based Christian schools of South Africa. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/26293/thesis_shula_mt.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Smith BN, Montagno RV & Kuzmenko TN 2004. Transformational and servant leadership: Content and contextual comparisons. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 10(4):80-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190401000406 [ Links ]

Spears LC & Lawrence M (eds.) 2004. Practicing servant-leadership: Succeeding through trust, bravery, and forgiveness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Steyn GM 2012. Reflections on school leadership focussing on moral and transformational dimensions of a principal's leadership practice. Tydskrif vir Christelike Wetenskap, 48(1/2):45-68. [ Links ]

Striepe M, Clarke S & O'Donoghue T 2014. Spirituality, values and the school's ethos: Factors shaping leadership in a faith-based school. Issues in Educational Research, 24(1):85-97. [ Links ]

Taylor C 2004. Modern social imaginaries. Durham, England: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor T, Martin BN, Hutchinson S & Jinks M 2007. Examination of leadership practices of principals identified as servant leaders. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(4):401-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701408262 [ Links ]

Valli A, Stefanski A & Jacobson R 2018. School-community partnership models: Implications for leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(1):31-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1124925 [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen PC 2015. Effective educational management. Cape Town, South Africa: Kagiso. [ Links ]

Van Dierendonck D & Patterson K (eds.) 2014. Servant leadership: Developments in theory and research. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Wallace TJ 2000. We are called: The principal as faith leader in the Catholic school. In TC Hunt, TE Oldenski & TJ Wallace (eds). Catholic school leadership: An invitation to lead. New York, NY: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Wolhuter C, Van der Walt H & Steyn H 2016. A strategy to support educational leaders in developing countries to manage contextual challenges [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 36(4):Art. # 1297, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n4a1297 [ Links ]

Received: 14 September 2020

Revised: 27 March 2022

Accepted: 21 July 2022

Published: 30 November 2022