Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 no.4 Pretoria nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n4a1992

ARTICLES

Developmental dyslexia in private schools in South Africa: Educators' perspectives

Salome GeertsemaI; Mia Le RouxII; Azima BhoratII; Aasimah CarrimII; Mishkaah ValleyII; Marien GrahamIII

IDepartment of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. salome.geertsema@up.ac.za

IIDepartment of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, as is globally, many people struggle with the challenges which emanate from developmental dyslexia (DD). It is thus important for educators to have adequate knowledge and a positive mindset regarding DD and the management thereof in the school context. One such important method of management is the accommodation of these learners in mainstream class. The quantitative survey study reported on here was aimed at determining the perspectives of educators in 2 private schools in the Tshwane South District, Gauteng, South Africa, regarding the knowledge of, attitude towards, and management of accommodations for learners with DD. We implemented a quantitative descriptive cross-sectional survey research approach where a self-administered questionnaire was administered after purposive sampling. Results indicate that the respondents, regardless of their qualifications, gender, or years of teaching experience, had limited knowledge of DD, but with a generally positive attitude towards inclusion and management of these learners. Furthermore, it was found that educators had an awareness of the terminology related to the accommodations that the education department granted these learners with DD. However, they were uncertain about the perceived path and nature of accommodations provided to learners. Specific details and related recommendations were explored.

Keywords: accommodations; developmental dyslexia; educators; private schools; specific learning disorders

Introduction

Developmental dyslexia (DD) is a distinct and significant impairment in the ability of an individual to read and/or spell (Charan & Kaur, 2017:9). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) classifies DD within the group of specific learning disorders under the broader category of neurodevelopmental disorders (APA, 2013). DD may not be a direct result of deficits in general intelligence and motivation, learning opportunity or sensory acuity, however, it may be due to a variation in normal anatomy and function of cognitive and language regions of the brain (Wajuihian, 2010:6). Attributable to this variation, numerous domains are affected.

DD as a developmental disorder manifests in different ways at different developmental stages in the affected domains (Bishop & Snowling, 2004:858). The areas impacted may include basic reading skills, written expression, speaking, and listening (Fisher, Francks, McCracken, McGough, Marlow, MacPhie, Newbury, Crawford, Palmer, Woodward, Del'Homme, Cantwell, Nelson, Monaco & Smalley, 2002:1186-1191). Initially the disorder is identified from a difficulty in learning letters and letter-sound association (Wajuihian, 2010:6). These evident challenges are followed by problems in learning letter combinations and reading words accurately, consequently resulting in an impaired reading rate and written expression skills (Wajuihian, 2010:6). The affected domains may negatively influence the career, communication skills, and health of a person with DD (Charan & Kaur, 2017:10). Research has shown that learners with developmental dyslexia (LWDD) are 2 or more years behind their chronological age regarding their reading abilities. However, if the reading deficit is associated with low levels of intelligence, the disorder is then referred to as a generalised learning disability (APA, 2013). DD may be a consequence of various circumstances which result in specific domains in the individual being affected.

The areas affected by DD can be attributed to its neuroanatomical basis (Krafnick, Flowers, Luetje, Napoliello & Eden, 2014:901). Researchers have observed through post-mortem studies that persons without DD present with an absence of the typical leftward asymmetry of the planum temporale as well as cortical anomalies indicative of neuronal migration errors during development, primarily in left hemisphere perisylvian regions (Krafnick et al., 2014:901). These persons have reduced grey matter volume (GMV) in several brain regions, mainly involving the left hemisphere perisylvian cortex, which is thought to be involved in written language (Krafnick et al., 2014:901). As a result of affected brain regions, a person with DD may present with a variety of symptoms.

These symptoms of DD are often physically evident in the educational settings (Griffiths, 2012:55). As such, learners must be accommodated for their unique way of learning to ensure academic success (Leseyane, Mandende, Makgato & Cekiso, 2018:5). Unfortunately, although supported by an organised application system in aid of inclusive learning, educators' knowledge of these accommodations and the nature of the application thereof, are needed for ultimate successful implementation. Preliminary global investigations pinpoint the caveats in this regard (Dovidio, Major & Crocker, 2000; Hoskins, 2015:34). Local research is, however, scarce, and nonspecific in terms of DD and its subsequent management in mainstream schools (Karande, 2009:382-391; Leseyane et al., 2018:5). We, therefore, investigated the perspectives of educators regarding the knowledge and management of learners with DD in private schools in South Africa.

Literature Review

The International Dyslexia Association (IDA) estimates that 15 to 20% of the general population experiences one or more symptoms of DD (IDA, 2017). Staff Reporter (2013) suggests that within South Africa one in 10 people has DD. Therefore, there may be approximately five million people in South Africa who have difficulty with specific literacy challenges at school or in the workplace (Leseyane et al., 2018:3). LWDD may also have some form of spoken or perceptual language difficulty (Wellington & Wellington, 2002:84-85). As a result, independent learning is affected and this includes reading, note taking, and using the internet (Wellington & Wellington, 2002:84-85). LWDD present with unique academic challenges. These challenges significantly impact on their studies as their ability to progress and attain achievement in reading, writing, numeracy, oral fluency, organisation, and self-esteem is negatively affected (Griffiths, 2012:55). Self-esteem is further impacted by different perceptions of the role players, such as the educators, in their scholastic environment.

Educators' expectations are often based on their judgements about individual learners regarding their academic potential (Hornstra, Denessen, Bakker, Van den Burgh & Voeten, 2010:516). Research has shown that educators' bias towards LWDD frequently affects how they interact with concerned pupils, leading to poor academic performance (Dovidio et al., 2000:1-28). The attitudes of educators may negatively influence their expectations for learners who display reading difficulties in classroom situations (Jussim & Harber, 2005:131-155). A limited number of international studies reflect the effect of educators' attitudes on LWDD. In a specific local study conducted by Leseyane et al. (2018) in the North West province of South Africa, learners expressed their experience with educators in public and special schools. These learners felt that educators in public schools lacked knowledge of DD and its management. This seemed to have a negative influence on the learners' academic performance (Leseyane et al., 2018:5). The impact of educators' limited knowledge of DD has also been reflected in an earlier study done by Karande (2009) in which learners had stated that they progressed better in subjects that were taught by educators who understood the challenges and difficulties that they encountered (Karande, 2009:382-391). Sander and Williamson (2010) suggest that learners with DD can be successful if the education system in which they are studying does not disadvantage them due to prejudicial perspectives towards their challenges. Educators must recognise the various effects of DD for LWDD to improve academically (Hoskins, 2015:34).

Differences in educators' expectations of LWDD versus learners without learning disabilities can be explained by accurate perception of lower levels of reading and spelling performance in LWDD. Furthermore, negative mental attitudes of educators regarding these learners can conceivably lead to differential treatment which results in increased differences in academic achievement (Hornstra et al., 2010:517).

The difference in educator treatment of LWDD in public and special schools was also investigated by Leseyane et al. (2018). The findings indicate that learners who had received education in public schools felt that educators were not patient with them, and that the support provided was not adequate. In contrast, the finding obtained from learners in special schools indicated that educators were patient with them and had knowledge on how to manage the challenges that they encountered (Leseyane et al., 2018:5-6). Olagboyega (2008:23) believes that inclusive learning implies that learners with learning difficulties, such as DD, can gain access to the curriculum without additional specialist support. This outcome can only be reached if the teaching and learning needs are supplemented so that learners are included therein (Leseyane et al., 2018:1). The educators' attitudes and high level of awareness about learning disabilities make the timely diagnosis of this disorder possible (Charan & Kaur, 2017:10). Early identification and treatment are key to helping LWDD achieve success in school and life in general (IDA, 2017).

Conceptual Framework

Since the 2000s, clinicians and educators aimed to elucidate caveats in the scholastic system where learners with specific learning needs can be accommodated. Sun and Wallach (2014) suggest such a conceptual framework in language-learning disorders for school-aged learners that includes both inherent and external factors pertaining to language abilities of the child. Focusing on the internal factors (what the child brings to class) as well as external factors (for example classroom dynamics), collaborative information sharing between the parents, educators, learners, and therapists can take place. As such, an integrated collaboration in the holistic management of these learners was highlighted as an important key to success. This framework guided our study, with the acknowledgement of more recent findings regarding the role of attitudes towards these learners as well.

Educators' expectations of LWDD may add an additional burden to prospective academic outcomes of these learners. Often these poor expectations and reactions towards LWDD stem from a lack of knowledge pertaining to this developmental challenge. Understanding the range of these educators' knowledge and their attitudes towards the inclusion of LWDD in the mainstream class context may lead to eventual solutions to address these issues. Improvements could be made in the understanding and attitudes of educators through informed advocacy for DD which may be achieved through educator training as this will assist LWDD. Educators may be empowered and may acquire better knowledge and understanding of DD.

The subsequent research question in this study was: What are the perspectives of South African educators pertaining to the knowledge of, and their attitudes towards, the accommodation of LWDD in schools?

Methodology

The aim with this research was to describe typical perspectives of South African educators pertaining to knowledge of, and attitudes towards, the accommodation of LWDD in private schools. A quantitative descriptive cross-sectional survey research approach was implemented. More specifically, a self-administered questionnaire was adapted from Jenn (2006), and the survey subsequently conducted. The quantitative approach was employed to yield specific data values from which deductions of significance could be calculated. The self-administered questionnaires were administered as these types of surveys maintain respondent anonymity and can easily be distributed to the population (Babbie, 2016).

Respondents

The respondents for this study had to meet the criteria as set out in Table 1. The respondents were purposively selected from two private schools in the Tshwane South District in Gauteng, South Africa.

Apparatus and Materials

The self-administered questionnaire comprised 31 closed-ended multiple choice questions. Some open-ended questions were also used in the section on feelings and attitudes towards DD. The educators were required to provide objective information on four factual questions. The structure of the questions was considered to avoid confusion thus achieving accurate results. Fixed alternative questions were used in which respondents were expected to choose between two or more answers. We also included Likert-type items with options of "strongly disagree", "disagree", "neutral", "agree", or "strongly agree." We compiled the questionnaire with the assistance of a qualified statistician working in the relevant academic field.

Research Procedure

Data were collected over a period of a month. An alphanumeric code was used to capture the responses from various respondents to ensure confidentiality. A statistician assisted with data analysis. A summary of the data was obtained using frequency distribution and contingency tables. We calculated percentages to reflect and draw conclusions from the respondents' responses. Specific statistical calculations and correlations were also computed with the STATA program. These calculations are included in the results section.

Research Ethics

Ethical clearance was granted by the Departmental Research and Ethics Committee of the Department of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, University of Pretoria. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before completing the questionnaire. No incentives were offered to coerce the subjects to participate, thus participation was voluntary. The purpose of the research study was explained in a letter attached to the questionnaire. Direct sampling entailed paper-based questionnaires which were delivered to the principals of the private schools. The principals offered their consent to distribute the questionnaires to educators and for data to be collected from them.

Confidentiality was ensured during sampling as the hard copy questionnaires did not require the names or any specific identifying information from the respondents. However, the names of the respondents' schools were known to the researchers. Conversely, these names remained confidential as we barred visibility thereof to other role players. The completed hard copy questionnaires were safely stored and classified as confidential information. These copies are stored in a designated space at the Department of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, University of Pretoria, for the recommended period of 15 years.

Reliability and Validity

A test-retest method was applied where the same measurement was made more than once to ensure the attainment of reliable results. Test-retest reliability relies upon administering the questions in a randomised order to a single participant on multiple occasions. Assuming no changes in the sample participant, the questions should return consistent results over multiple administrations (Babbie, 2016). Upon request, a pilot respondent was randomly chosen from the staff list by one of the principals. This respondent completed the questionnaire on three separate occasions during a single week. The questions were included in a different randomised order on each occasion. This pilot participant did not take part in the actual study. No changes occurred within this pilot respondent, and the questions returned consistent results over the three administrations of the questions in the questionnaire. To ensure face validity the aims of the research project were stated in the cover letter to the questionnaire. Questions included in the survey covered the objectives, thus additionally ensuring face validity. Finally, we included both open- and closed-ended questions to ensure construct validity.

Results

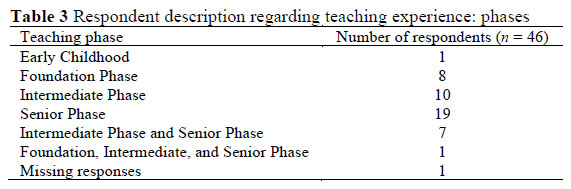

The main aim with this study was to describe typical perspectives of South African educators pertaining to knowledge of, and attitudes towards the accommodation of LWDD in private schools. An important aspect to consider in the results is that not all respondents answered all given questions, therefore, the number of respondents for each question varied. Tables 2 and 3 display the nature of teaching experiences for the different respondents (n = 47). Forty-seven respondents can be regarded as an acceptable response rate for the population of 110 staff members from which the necessary data were derived (Christensen, Johnson & Turner, 2015).

As a measure of internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was applied to the questionnaire after completion thereof. To ensure reliability, a test-retest method was applied where the same measurement was made more than once to ensure reliable results. Test-retest reliability relies upon administering the question to a single participant multiple times as described in the reliability and validity section. Assuming no changes in the sample subject, the questions should return consistent results over multiple administrations. The final Cronbach's alpha was 0.73, which indicates that the questionnaire had an acceptable reliability since the Cronbach's alpha should be > 0.7. The results are presented according to the objectives stated in the methodology section.

To Determine the Nature of the Knowledge of Private Mainstream School Educators regarding DD The questions were focused on the nature, prevalence, risk factors associated with DD, and support available for LWDD. More specifically, we investigated whether educators' higher qualifications and more teaching experience correlated with educators having more knowledge pertaining DD. Firstly, regarding qualifications, we posed questions to determine the types of qualifications that the respondents possessed (Figure 1). These qualifications were categorised into the following groups: Advanced Certificate in Education (ACE), higher certificate or diploma, undergraduate degree, and honours degree or higher. Responses indicated that educators with an honours degree or higher scored an average of 51.56% in the questionnaire. These educators scored higher on knowledge about DD than educators with an undergraduate degree (47.32%) and educators with an ACE, higher certificate, or diploma (48.75%). To test for the significance of the differences between these three independent groups, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test. The p-value obtained from this test was 0.595. Since the p-value of the Kruskal-Wallis test was > 0.05, no statistically significant difference was found between the percentage of correct answers attained by participants from different groups of qualifications.

Secondly, to determine male or female educator dominance regarding knowledge of DD, biographical information was obtained from respondents regarding their gender. There were four male and 40 female respondents. Male respondents scored an average of 54.8% and female respondents scored an average of 47.1%. To test for differences between these two independent samples, we used the Mann-Whitney test. The p-value obtained from this test was 0.577. Since the p-value of the Mann-Whitney test was greater than the set 0.05, this value indicates that there was no statistically significant difference between the percentage of correct answers attained by males and female respondents.

Thirdly, to determine whether educators with more teaching experience had more knowledge of DD, information regarding the educators' years of teaching experience was obtained. The results indicate that educators with 15 or more years of teaching experience obtained the highest average (51.7%). The Kruskal-Wallis test yielded a p-value of 0.635 which is > 0.05. As such, no statistically significant difference was determined for the percentage of correct answers attained by educators with differing years of teaching experience. Figure 2 reflects the relationship between the years of teaching and knowledge about DD.

Finally, phase experience was also investigated. This type of experience related to the specific knowledge about DD according to the phase of teaching (Table 4).

To test for significance of differences between these independent groups, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test. The p-value obtained from the Kruskal-Wallis test for significant differences between phases was 0.082, which is greater than the set 0.05. Thus, there was no statistically significant difference between the percentage of correct answers attained by educators teaching in different school phases.

To Determine the Educators' Perceived Roles in Accommodations for LWDD

From a total of 47 respondents (n = 47), results from 44 responses (n = 44) indicate the following choices for educators regarding their perceived roles in providing accommodation for LWDD (cf. Table 5). An accommodation is a change in how a learner with DD will study the same material as peers involving, for example, larger print, additional time, smaller group settings, and the use of assistive technology and support staff (Geertsema & Le Roux, 2020).

To Determine the Educators' Perceived Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Accommodations for LWDD

The following statements and questions were posed to educators and the results are presented thereafter: "Accommodations are adjustments made to allow a learner to demonstrate knowledge, skills, and abilities without lowering learning and without changing what is being assessed, for example, providing text in audio-format when academic knowledge is being assessed."

The findings show that 75% of educators knew what the term "accommodation" meant. These findings, as depicted in Figure 3, also suggest that most of the educators understood the terms "reader", "scribe", and "prompter." Of this majority, the term "reader" was the least and "scribe" the best known.

What is the perceived path for learners to be granted accommodations via the Department of Education?

Of the 47 respondents, only a few responded and the rest indicated that they did not know what the path of application for accommodations entailed. The results from the few respondents (n = 9) indicate the following regarding their knowledge and attitudes towards accommodations (cf. Table 6).

What is your school's point of view regarding accommodations?

Responses from 45 educators indicate that 68.9% believed that accommodations should be provided to learners; 6.7% indicated that accommodations should not be provided, and 24.4% were indecisive. Although representative of a positive trend towards the provision of accommodations, when considering the educators' indecisiveness, these figures may also support a general uncertainty due to a lack of knowledge regarding the actual accommodations.

To Determine whether the Participating Private Schools Provided Accommodations to Learners with DD

Responses from 44 respondents indicate that 25% of the participating schools provided accommodations, 45.5% did not, and 29.5% of respondents were unsure whether their schools provided accommodations or not.

Four respondents elaborated on the types of accommodations that their schools provided. Of the four respondents, the first indicated that readers, scribes, and extra time were provided, the second that readers and scribes were provided, the third that scribes were available and the last respondent indicated that occupational therapy was provided.

To Determine Educators' Perceived Barriers in Supporting LWDD and what Additional Support Educators would Recommend for LWDD Which barriers do educators face in providing support for a learner with DD? Educators regarded a lack of resources, not enough teacher training, large class sizes, and learners struggling to complete tasks in the allocated time as barriers.

What additional support/resources would educators recommend for learners with DD?

The key points that emerged from the 23 responses were the following: the use of pictures, sand trays/use of senses, smaller classes, the provision of occupational therapy, the keeping of a technology diary, the use of audio books, and a remedial teacher.

Discussion

With this research study we investigated typical perspectives of South African educators pertaining to knowledge of, and attitudes towards, the accommodation of LWDD in private schools in Gauteng, South Africa. The findings relating to the initial objective pertaining to the knowledge of educators about DD suggest that there was no statistical difference in the results on the knowledge about DD of the different groups of people with varying qualifications. From these findings, we can conclude that South African educators in private schools have an average to below-average knowledge of DD. In a study conducted by Charan and Kaur in 2017, a cross-sectional survey was employed to assess the knowledge and attitudes regarding DD among educators at selected schools in Punjab, India. Findings from this study correlate with those of our study in that educators' qualifications did not have an impact on their knowledge about DD.

Subsequent to qualifications, the correlation between knowledge and gender was also determined. We concluded that gender had no impact on South African educators' knowledge regarding DD, which is in line with Charan and Kaur's (2017) findings. The findings from both studies show no statistically significant difference between the percentage of correct answers attained by male and female respondents. This outcome is encouraging as developing countries such as India and South Africa have inherited gender inequalities from previous regimes and are committed to promoting inclusive educational policies.

We further investigated the correlation between the educators' years of teaching experience and their knowledge of DD. The findings show that the number of years of teaching experience had no influence on the educators' knowledge of DD. In a study conducted by Echegaray-Bengoa, Soriano-Ferrer and Joshi in Peru in 2017, the knowledge, misconceptions, and knowledge gaps of pre-service teachers (PSTs) and in-service teachers (ISTs) were investigated using the Knowledge and Beliefs About Developmental Dyslexia Scale (KBDDS). The findings suggest that knowledge about DD positively correlated with years of teaching experience. A few possible factors may be the reason for the different outcomes in the studies in Peru and South Africa. The most probable is that the Peruvian studies of Echegaray-Bengoa et al. (2017) and the slightly earlier one of Soriano-Ferrer, Echegaray-Bengoa and Joshi (2015), both focused on educators in their early years of teaching. The scholastic system in Peru also provides a special remedial stream in their Foundation Phase where these teachers would get in-service training and hands-on experience regarding specific learning disorders such as DD (Soriano-Ferrer et al., 2015). As such, educators in both Peruvian studies may have benefitted from added experience relating to the specific approaches of in-service training for remedial and early childhood education. This type of in-service training is, unfortunately, absent locally. Also, the Foundation Phase in South Africa does not provide a remedial stream in mainstream private education, and most of the respondents in our study worked in the Senior Phase (Table 3). In summary, educators in our research, irrespective of their qualifications, gender, number of years of teaching experience, and the different phases that they taught, lacked adequate knowledge of DD and there was no significant distinction between these groups regarding this lack of knowledge.

The lack of expertise regarding DD may stem from limited education training in this regard. This, in turn, may result in educators having a lack of awareness on the inclusion of learners with DD (Forlin, 2013). If educators have sufficient knowledge of DD, this will result in a more positive attitude towards LWDD (Taylor & Coyne, 2014). Such adequate knowledge of DD and positive attitudes should undoubtedly comprise the successful management thereof. We, therefore, also included information regarding the accommodations provided to these learners in the classroom context.

From our investigation into the perceived roles of educators regarding the provision of accommodations, we concluded that the near majority of educators (17 educators) believed that they needed to attend appropriate departmental courses to provide accommodations to LWDD. This is correct in that educators need to attend training by the District Based Accommodations Committee (DBAC) or Provincial Based Accommodations Committee (PBAC) to be allowed to act as a scribe and/or reader. Eight educators believed that their role was to be a reader, scribe, and prompter, however, these educators (n = 8) were not aware that they needed to attend the appropriate departmental courses to be able to provide these accommodations. Seven educators believed that their role was only to be a reader. This perception may be due to the common misconception that DD is uniquely a reading disorder (Bishop & Snowling, 2004). Similar results were reported in a study by Echegaray-Bengoa et al. (2017). Of the remainder of the educators, three believed that their role was only to be a scribe, six believed that their role was only to be a prompter, three believed that their role was to be a reader and a prompter, and three educators did not answer this question. It is somewhat alarming that only 17 respondents of the 47 believed that they needed to attend appropriate departmental courses to provide accommodations. It is suggested that, if educators knew their roles in providing accommodations for LWDD, they may be able to provide them with the necessary support. Regrettably, it is clear that South African educators in private schools are not entirely sure of this role, nor that it necessitates additional qualifications. According to Education White Paper 6 (Department of Education, 2001) regarding special needs education to build an inclusive education and training system, only 20% of learners with disabilities were accommodated in special schools. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 2.2% and 2.6% of learners in any school system could be identified as disabled or impaired. These numbers would imply that there are 400,000 disabled or impaired learners in South Africa. In 2001, statistics indicated that approximately 64,200 learners with disabilities or impairments in about 380 schools were accommodated for. Therefore, potentially 280,000 learners with disabilities or impairments were unaccounted for. This high number of both identified and unaccounted learners logically implicates the importance of appropriate knowledge and training regarding accommodation support for these learners.

In addition, we report on the terminology about accommodations. Seventy five percent of the respondents understood the term "accommodation" and a further 81.8% understood the terms "reader", "scribe", and "prompter." Although many of the educators seemed to understand the terminology regarding accommodations, it should be noted that 80.9% of educators did not answer the question pertaining the perceived path for learners to be granted accommodations. This alarming number may indicate a lack of knowledge regarding the practicalities of ensuring that LWDD received the support they need. The Department of Basic Education (dBE, 2019) noted the following summarised procedures regarding the granting of accommodations to learners in mainstream schools: (1) The school should identify learners who meet the requirements for accommodations in terms of examinations, assessments and the type of support required. (2) Parents should be informed about assessment results and recommendations and relevant reports should be obtained. (3) The initial assessment will be conducted by the School Based Accommodations Committee (SBAC) and relevant information should be obtained from specialised support services provided at the school. (4) All documentation should be submitted to the DBAC. The DBAC will then mediate relevant policies and provincial guideline documents to the SBAC. (5) A DBAC management and training plan will be developed and submitted to the PBAC for quality assurance and approval. Further assessments will be conducted by the DBAC if necessary. (6) Verification of the documentation of learners from the SBAC will be considered and appropriate accommodations in terms of the DBE form 124 will be processed. (7) The approval of readers and scribes will be done by the PBAC.

In spite of the above, not only should educators have knowledge of terminology that relates to different types of accommodations, it is also important that they understand the departmental regulations and processes involved in applying for these. As such, it is imperative that schools are positive about the processes and are willing to follow them so that they are in a better position to provide these accommodations to LWDD.

We found that the majority (45.5%) of educators from the mainstream private school who responded to this survey did not provide accommodations for LWDD. LWDD have the potential to reach academic success since DD does not impact their intelligence (Démonte, Taylor & Chaix, 2004). Unfortunately, this aptitude is negatively impacted by a lack of provision of accommodations. As reported earlier, a lack of adequate provision may possibly arise from inadequate knowledge regarding the qualifications needed to act as reader, prompter, or scribe. Furthermore, tedious departmental processes may also hinder the successful integration of accommodations in different schools. We urgently need to address these challenges for South African LWDD to succeed academically. Moreover, even though accommodations may be provided to a certain extent, educators may still face barriers in supporting LWDD in the classroom (Leseyane et al., 2018). As such, we need to investigate additional methods of ongoing classroom support to help them overcome these barriers. The respondents also yielded their perspectives on some of these barriers. Finally, it is startling that these results are from mainstream private schools where one assumes that resources and support are readily available. Numbers in mainstream public schools may, therefore, be even more distressing.

The respondents in our study were of the opinion that there was a lack of resources, not enough teacher training, large class sizes, and that learners struggled to finish tasks within the allotted time. These perspectives are not exclusive to South Africa, but it seems as these are global challenges. Elias (2014) reports on the attitudes and knowledge of secondary school teachers in New Zealand on LWDD. The results indicate similar findings as in our South African study. The respondents in the New Zealand study indicated that they were under-qualified and overworked and could not integrate effective learning strategies for LWDD in the classroom. In addition, these educators felt that more teacher training on DD was required. They also felt that large class sizes impacted educators' capacity to assist LWDD. In a study by Stampoltzis, Tsitsou and Papachristopoulos (2018) on educators' attitudes towards teaching LWDD in Greek public primary schools, the respondents elaborated on the barriers in supporting LWDD. The Greek educators felt that there was a lack of teacher training and parallel support provided by a second teacher in the classroom and by the state. In our study, respondents recommended that additional support should be provided to LWDD, namely, the use of pictures, sand trays/use of senses, smaller classes, audio books and technology diaries, remedial teachers, and occupational therapists. It is important to stress that educators should have adequate knowledge about DD to provide effective classroom support to overcome barriers. This view is reiterated by the findings in a Zimbabwean study by Chitsa and Mpofu (2016) that educators' lack of knowledge hinders the provision of appropriate support to LWDD.

Conclusion

In South Africa, one in 10 people have DD (Staff Reporter, 2013). It is, therefore, important for educators to have adequate knowledge about DD as this will result in more positive attitudes towards LWDD (Taylor & Coyne, 2014). When educators have an extensive understanding of DD, they should be able to identify learners that may possibly present with DD and provide appropriate support to these learners.

With this study we found that South African mainstream private school educators, regardless of their qualifications, gender, or years of teaching experience, had average to below average knowledge of DD. Programs should, therefore, be put in place to enhance educators' knowledge regarding DD. This type of support may, in turn, promote the development of LWDD as their special needs will be accommodated. We suggest that tertiary level educators should be trained on DD. Gwernan-Jones and Burden (2010) suggest that postgraduate teacher training should include modules that comprise ways to help learners with learning difficulties in general and learners with DD. Specific educator training pertaining to educator knowledge of DD, inclusion, and accommodations may inculcate positive attitudes among them and increase their self-efficacy beliefs (Indrarathne, 2019). Finally, it was found that educators had knowledge of the terminology related to accommodations, however, they were unaware of the perceived path to provide such accommodations. Educators should be informed about the processes to be followed in order for them to assist these learners to obtain the accommodations that they qualify for as soon as possible.

Recommendations for Future Research Within the South African context, further research needs to be conducted on educators' knowledge and attitudes towards LWDD in public schools as well. The research should be conducted in urban and rural settings alike, focusing on underserved communities. To acquire more in-depth information in this regard, interviews rather than the completion of a questionnaire should be considered and larger samples from all over South Africa should be considered for future research.

Authors' Contributions

SG and MLR developed the concept and design, and wrote the article. AB, AC, and MV collected and captured the data and assisted in the writing of the article based on their research. MG assisted with the statistics and descriptive analyses in the results section.

Notes

i. This article is based on an honours research project by AB, AC, and MV.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ Links ]

Babbie E 2016. The practice of social research (14th ed.) Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Bishop DVM & Snowling M 2004. Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin, 130(6):858-886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.858 [ Links ]

Charan GS & Kaur H 2017. A cross-sectional survey to assess the knowledge and attitude regarding dyslexia among teachers at selected schools, Punjab. International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research, 2(3):9-14. [ Links ]

Chitsa B & Mpofu J 2016. Challenges faced by grade seven teachers when teaching pupils with dyslexia in the mainstream lessons in Mzilikazi District Bulawayo Metropolitan province. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 6(5):64-75. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-0605016475 [ Links ]

Christensen L, Johnson RB & Turner LA (eds.) 2015. Research methods, design, and analysis (12th ed). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Démonte JF, Taylor MJ & Chaix Y 2004. Developmental dyslexia. The Lancet, 363(9419):1451-1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16106-0 [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2019. Information for teachers: Initial teacher education. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Informationfor/Teachers/InitialTeacherEducation.aspx. Accessed 2 March 2019. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Education White Paper 6. Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/ Portals/0/Documents/Legislation/ White%20paper/Education%20%20White%20Paper%206.pdf? ver=2008-03-05-104651-000. Accessed 5 September 2019. [ Links ]

Dovidio JF, Major B & Crocker J 2000. Stigma: Introduction and overview. In TF Heatherton, RE Kleck, MR Heble & JG Hull (eds). The social psychology of stigma. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Echegaray-Bengoa J, Soriano-Ferrer M & Joshi RM 2017. Knowledge and beliefs about developmental dyslexia: A comparison between pre-service and in service Peruvian teachers. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 16(4): 375-389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192717697591 [ Links ]

Elias R 2014. Dyslexic learners: An investigation into the attitudes and knowledge of secondary school teachers in New Zealand. Master of Professional Studies in Education dissertation. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland. Available at https://www.dyslexiafoundation.org.nz/dyslexia_ad vocacy/pdfs/re_dissertation_2014.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Fisher SE, Francks C, McCracken JT, McGough JJ, Marlow AJ, MacPhie L, Newbury DF, Crawford LR, Palmer CGS, Woodward JA, Del'Homme M, Cantwell DP, Nelson SF, Monaco AP & Smalley SL 2002. A genomewide scan for loci involved in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Human Genetics, 70(5):1183-1196. https://doi.org/10.1086/340112 [ Links ]

Forlin C 2013. Issues of inclusive education in the 21st century. Journal of Learning Science, 6:67-81. [ Links ]

Geertsema S & Le Roux M 2020. Managing developmental dyslexia: Practices of speech-language therapists in South Africa. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 14(1):71 -98. https://doi.org/10.17206/apjrece.2020.14.1.71 [ Links ]

Griffiths S 2012. 'Being dyslexic doesn't make me less of a teacher'. School placement experiences of student teachers with dyslexia: Strengths, challenges and a model for support. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(2):54-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01201.x [ Links ]

Gwernan-Jones R & Burden RL 2010. Are they just lazy? Student teachers' attitudes about dyslexia. Dyslexia, 16(1):66-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.393 [ Links ]

Hornstra L, Denessen E, Bakker J, Van den Bergh L & Voeten M 2010. Teacher attitudes toward dyslexia: Effects on teacher expectations and the academic achievement of students with dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(6):515-529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219409355479 [ Links ]

Hoskins GA 2015. Exploring the learning experiences of grades 6-9 dyslexic school learners in a long term remedial school. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/20109/dissertation_hoskins_ga.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Indrarathne B 2019. Accommodating learners with dyslexia in English language teaching in Sri Lanka: Teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and challenges. Tesol Quarterly, 53(3):630-654. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.500 [ Links ]

International Dyslexia Association 2017. IDA fact sheets. Available at https://dyslexiaida.org/. Accessed 14 March 2019. [ Links ]

Jenn NC 2006. Designing a questionnaire. Malaysian Family Physician, 1(1):32-35. [ Links ]

Jussim L & Harber KD 2005. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(2):131-155. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3 [ Links ]

Karande S, Mahajan V & Kulkarni M 2009. Recollections of learning disabled adolescents of their schooling experiences: A qualitative study. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 63(9):382-391. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5359.56109 [ Links ]

Krafnick AJ, Flowers DL, Luetje MM, Napoliello EM & Eden GF 2014. An investigation into the origin of anatomical differences in dyslexia. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(3):901-908. https://doi.org/10.1523/INEUROSCL2092-13.2013 [ Links ]

Leseyane M, Mandende P, Makgato M & Cekiso M 2018. Dyslexic learners' experiences with their peers and teachers in special and mainstream primary schools in North-West Province. African Journal of Disability, 7(0):a363. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v7i0.363 [ Links ]

Olagboyega KW 2008. The effects of dyslexia on language acquisition and development. MEng dissertation. Akita, Japan: Akita International University. [ Links ]

Sander P & Williamson S 2010. Our teachers and what we have learnt from them. Psychology Teaching Review, 16(1):61-69. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ891118.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Soriano-Ferrer M, Echegaray-Bengoa J & Joshi RM 2015. Knowledge and beliefs about developmental dyslexia in pre-service and in-service Spanish speaking teachers. Annals of Dyslexia, 66(1):91-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-015-0111-1 [ Links ]

Staff Reporter 2013. Addressing the challenges of dyslexia. Mail & Guardian, 20 September. Available at https://mg.co.za/article/2013-09-20-00-addressing-the-challenges-of-dyslexia. Accessed 18 October 2018. [ Links ]

Stampoltzis A, Tsitsou E & Papachristopoulos G 2018. Attitudes and intentions of Greek teachers towards teaching pupils with dyslexia: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Dyslexia, 24(2): 128-139. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1586 [ Links ]

Sun L & Wallach GP 2014. Language disorders are learning disabilities: Challenges on the divergent and diverse paths to language learning disability. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(1):25-38. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000005 [ Links ]

Taylor L & Coyne E 2014. Teachers' attitudes and knowledge about dyslexia: Are they affecting children diagnosed with dyslexia? Dyslexia Review, 25:20-23. [ Links ]

Wajuihian SO 2010. Prevalence of vision conditions in a South African population of African dyslexic children. MOptom thesis. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/9964/Wajuihian_Samuel_Otabor_2010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Wellington W & Wellington J 2002. Children with communication difficulties in mainstream science classrooms. School Science Review, 83(305):81-92. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jerry-Wellington/publication/237432638_Children_with_communication_difficulties_in_mainstream _science_classrooms/links/55195ba60cf21b5da3b84a38/Children-with-communication-difficulties-in-mainstream-science-classrooms.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2022. [ Links ]

Received: 16 April 2020

Revised: 30 May 2021

Accepted: 14 February 2022

Published: 30 November 2022