Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 no.3 Pretoria ago. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n3a2133

Parental involvement in children's primary education: A case study from a rural district in Malawi

Guõlaug ErlendsdóttirI; M. Allyson MacdonaldI; Svanborg R. JónsdóttirII; Peter MtikaIII

IFaculty of Education and Diversity, School of Education, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland gue14@hi.is

IIFaculty of Education and Pedagogy, School of Education, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

IIISchool of Education, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

In the study reported on here, we analysed parents' involvement in their children's primary education in 4 primary schools in rural Malawi, focusing on the home and the school. Through interviews and focus-group discussions, information was obtained from 19 parents, 24 teachers (6 from each school), and 4 head teachers. Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory was used to design the study and to interpret the data, focusing mainly on the micro- and mesosystem elements. The home and school settings represent the autonomous microsystem, whereas parental involvement is part of the mesosystem. The microsystem appeared to be active both with learner-parent and learner-teacher actions; however, mesosystemic interactions were limited. We found that parents and teachers needed to develop stronger mutual relationships and interactions to support learners better. Schools also need to communicate positive aspects of children's learning to the parents. Enhancing positive reinforcement could enhance parental involvement.

Keywords: ecological systems theory; home settings; Malawi; parental involvement; parent-teacher communication; primary school education; rural schools

Introduction

Education is considered a fundamental human right and is regarded as a key factor in developing human capital (Lumadi, 2019). In many sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, including Malawi, education is recognised as a means for expanding human capabilities and choices (Sen, 1999). For the individual, quality education teaches employability skills, provides employment opportunities, increases earnings, and improves health. For society in general, quality education stimulates innovation, strengthens institutions, and improves social cohesion (United Nations [UN], 2018; World Bank, 2018). The importance of education is encapsulated in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 4 - Quality education for all - which includes lifelong learning in inclusive settings (UN, 2015).

While many developing countries have primary school enrolment of above 90%, more than 600 million young people worldwide still fall short of basic literacy and numeracy skills - even after completing primary education (UN, 2018). As of 2017, about 90% (202 million) of school-aged children and adolescents in SSA were not achieving minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2017). A major challenge facing education systems in SSA is that children in the early grades come to school poorly prepared, reading materials are in short supply, and attendance is irregular. This results in poor school experiences, low educational attainment, low pass rates, and high drop-out rates as children fail to transition into secondary schools.

One component affecting quality education and academic achievement is parental involvement (Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003; El Nokali, Bachman & Votruba-Drzal, 2010). The purpose of studying parental involvement in rural Malawi was to acquire a deeper understanding of how parents participated in their children's education in the region. This study should expand our knowledge of the dynamics and importance of parental involvement when it comes to educational attainment. With the study we addressed the focus of SDG number 1, striving for poverty eradication through education (UN, 2015).

Parental interest and involvement in children' s education are vital for academic achievement (Dahie, Mohamed & Mohamed, 2018; El Nokali et al., 2010; Lumadi, 2019). Research has established that parental-school involvement benefits children from all walks of life in their pursuit of academic achievement (Uludag, 2008). For example, Wang and Sheikh-Khali (2014) note the role that parents can play in supporting children with home-based learning activities such as homework supervision. Other studies (e.g., Wei & Ni, 2023) highlight the role that parents can play through involvement in school governance, which has the potential to contribute to improved children's learning outcomes and school efficiency. Additionally, research has shown that complex factors influence attainment. These comprise "students' personal factors, their interactions with others such as parents, teachers, and administrators, and the larger systems that surround the students such as school districts, neighbourhoods, local economy, political policy, and multicultural relations" (Bertolini, Stremmel & Thorngren, 2012:2). However, for parents to become involved, an invitation is considered a key motivating factor. The three most important sources of invitation are the school climate, teachers, and learners (Hoover-Dempsey, Walker, Sandler, Whetsel, Green, Wilkins & Closson, 2005; Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). A positive school climate generates a welcoming feeling and conveys that parental involvement is supported and valued. A direct invitation to various activities from the teacher is also essential. The third source of invitation is the children themselves and their attitudes towards parental involvement.

With this study we aimed to describe how parents in rural Malawi participated in their children's education and how schools involved parents. The focus was on home and school settings as the location of parent-school interaction, which was linked to academic achievement (El Nokali et al., 2010). We applied the ecological systems theoretical framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) as a lens in this study to scrutinise parent-school interaction. It was within the context of the above exposition that the following research questions emerged:

1) How do parents in rural Malawi participate in their children's education?

2) How do four rural primary schools involve parents in their children's education?

School-home relationships have received much interest and are well-developed in many high-income countries in Europe, the United States of America (USA), and Australia. Within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, school-home issues have been addressed in several studies using the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS). However, there has been less research on parental involvement within SSA countries. Only a few studies (e.g., Marphatia, Edge, Legault & Archer, 2010) have directly explored the nature of parental involvement in rural schools in Malawi. With this study we addressed that research gap, focusing on four rural primary schools.

Parental involvement in their children's education has been defined as "parents' interactions with schools and with their children to promote academic success" (Hill, Castellino, Lansford, Nowlin, Dodge, Bates & Pettit, 2004:1491). Home-setting activities include parents discussing education with their children, showing interest in their children' s education, reading to and with them, and providing homework support. Activities in the school setting include parent-teacher communication and parents attending meetings at school, among others (Dahie et al., 2018; Dearing, Kreider, Simpkins & Weiss, 2006; Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003; El Nokali et al., 2010).

The motivation for this study came from the field researcher's experience as a volunteer for many years in small non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Namibia and Malawi. She visited many rural primary schools in both countries and observed the teachers' resilience in facing endless challenges. This left her with a lasting impression, along with an interest in examining various facets of primary education. By understanding the nature of parental involvement in rural primary schools in Malawi, steps can be taken by authorities to improve educational outcomes and thus increase children's potential.

Theoretical Background

To understand the different roles in the school and home and how they influence one another, we turned to Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory (EST). This theory postulates that individuals develop through reciprocal interactions and relationships within the community and broader society (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). EST comprises four systems in a nested structure, each embedded in the next. The developing individual is at the core, nested in the microsystem, which involves processes and structures in the individual's immediate surroundings. The mesosystem is a system of microsystems and links two or more settings in the microsystem and the social setting. Events in the exosystem affect the individual without that person having an active role within that system. The macrosystem includes cultural values, customs, ideology, belief systems, and laws in the developing individual's context. It is through the interconnection of these systems that the individual develops.

EST has been applied to research children's well-being through the years. Seginer (2006) examined factors that are often overlooked but affect parental involvement, namely, culture and ethnicity. Seginer aimed to recount the relations between parents' involvement and their children' s educational outcomes by applying Bronfenbrenner' s EST. Seginer focused on immigrant and minority groups and home-based involvement in the microsystem. Seginer focused on interrelations between elements in the microsystems and school-based involvement. The interpersonal context where the developing individual is not an active participant belongs in the exosystem. Lastly, Seginer investigated the cultural context through the macrosystem.

Lewthwaite (2006) applied Bronfenbrenner' s EST focusing on the development of science teacher leaders in primary schools in New Zealand. Teachers identified both personal and environmental factors, and their interaction either supported or hindered teachers' development as science teacher leaders. EST has proven to be suitable for understanding an individual' s development and accounting for complex systems in the school and home contexts (Johnson, 2008), such as parental involvement.

In our study, the main focus was on home and school settings, which, within an ecological framework, represent autonomous microsystems, whereas parental involvement is conceptualised as part of the mesosystem comprising interactions between microsystems. The different systems and elements for each system are presented in Figure 1.

Context of the research

In 2018 the Malawian population had reached 17.5 million, of which 52% were younger than 18 years (National Statistical Office, 2019). About 87% of Malawian school-aged children were enrolled in primary schools (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology [MoEST], 2016). Primary schooling is supposedly free of charge, however, parents and guardians are responsible for various costs to ensure their children's place in school, such as contributing towards a general purpose fund (GPF) and buying school materials and uniforms for their children. At an official level, there is no mechanism to implement compulsory education from Standard 1 to 8. On average, people in Malawi receive 4.5 years of schooling (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2018), and the national literacy rate is 69% (National Statistical Office, 2019).

Teacher shortages make it difficult for education authorities to hire qualified staff for all schools. In 2018 the national learner/qualified teacher ratio was 70:1 despite the national target of 60:1 by 2017 (MoEST, 2018). In 2018, it was estimated that the national survival rates from Standard 1 to 5 and Standard 1 to 8 were 61% and 41% respectively. The primary completion rate of 52% has remained relatively unchanged in recent years. Other challenges that the public education sector faces include a poor supply of teaching and learning materials and a lack of infrastructure (MoEST, 2018). Enrolment in recent decades has increased; however, due to high drop-out and repetition rates, the increase appears only in the standards for younger learners (Chimombo, 2005).

Economic and cultural factors in Malawi influence parents' attitudes and ability to support their children' s education. This is especially true in densely populated rural areas with low literacy levels and where livelihoods are based on subsistence agriculture. When school-aged children begin participating in income-generating activities, school attendance is affected by increased dropout (Chimombo, 2005). The gendered nature of parents' investment in education also undermines girls' rights to education. In some communities, parents may view sending their daughters to school as less profitable since many will become part of their husband' s households after marriage (Marphatia et al., 2010; Mzuza, Yudong & Kapute, 2014).

Methodology and Method

In this qualitative study we focused on parents and their involvement in education and the interaction between parents and teachers in home and school settings in the southern district of Mangochi in Malawi. Data were collected from some teachers and head teachers. Learners were not involved in this study; we chose to focus on parents and teachers - the adults in the school community. Standard qualitative methods of data collection -interviews and focus-group discussions - were selected as the means of obtaining information, which involved translation. The objective of the investigation was to understand the nature of parental involvement and how schools involved parents by answering the research questions mentioned earlier. We were interested in exploring the subjective meaning of the lived experiences of parents and school personnel concerning parental involvement.

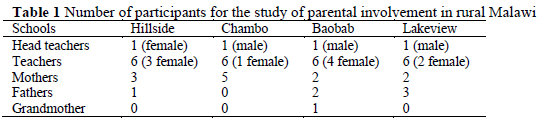

A purposive approach underpinned by pragmatism was used to select participants. We recruited 19 parents whose children attended the respective schools at the time of data collection. We also considered their availability at the time and their willingness to participate. Six teachers from each of the four schools also participated in the study, with four head teachers representing the four schools. Table 1 provides a summary of the participants in this study.

All four schools were situated in impoverished communities. The schools were characterised by overcrowded classrooms, a shortage of qualified teachers, poor provision of teaching and learning materials, and inadequate infrastructure. These conditions challenged effective teaching and learning. An overview of the size of the four schools is given in Table 2, with information based on data collected by the first author at each school.

One focus-group discussion was conducted with parents from each school. The parents were asked about their views on education and whether they read to or with their children. Teachers were interviewed in pairs and asked their opinions about parental involvement and whether parents visited the school. Head teachers were interviewed individually and asked whether they believed that parents valued education and whether the head teachers invited parents to school events. These questions, along with others, were aimed at obtaining information from each participant on parental involvement and intended to shed light on the relationship between homes and schools and whether the schools encouraged parental involvement. The focus-group discussions and interviews were audio-recorded with participants' permission and lasted between 35 and 50 minutes. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured, and participation was voluntary.

Data Analysis

All focus group discussions and interviews were transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed (Clarke & Braun, 2017). Transcripts were read and re-read to gain insight into the data, in line with what Creswell (2012:243) terms "preliminary exploratory analysis." All points of interest were highlighted, and all transcribed interviews were summarised. The next step was to use the emergent codes related to the interview questions and relevant literature. These codes were further categorised into three sub-themes: parents' perceptions about education; reading and homework; and parent-teacher communication. Lastly, those sub-themes were further arranged around two site-specific main themes: home-setting and school-setting activities. Identifiers for participants and schools are provided at the end of each quote. "PFG" indicates that the quote originated from a parent focus group, "HT" is used for head teachers, and "T" is used for teachers. Thus, "T1 Lakeview" represents a quote from Teacher 1 from Lakeview primary school.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical requirements were strictly adhered to throughout the research process. After acquiring ethical approval for this study from the MoEST and Mangochi District Educational Authority, four rural primary schools in the Mangochi district were selected for data collection. Pseudonyms were assigned to each of the schools. Head teachers were informed about the purpose, motivation, and goal of the study. Their consent was obtained, and a data collection schedule was developed. The main ethical rule, "do no harm", as recognised by Madge (1997:114), guided the study. We opted for a brief personal disclosure (Braun & Clark, 2013:93) at the beginning of each interview to build collegial rapport. We considered it important to inform participants that the field researcher was a teacher by profession and had lived in SSA with her family for many years, including 5 years in Malawi. This was an attempt to reassure the participants that she was on familiar ground since she had purposefully sought to get to know the school system during her stay in Malawi. Throughout the data collection period, 5 consecutive days were spent at each school. During that time the field researcher experienced a friendly atmosphere at each school and a collegial ambience among the teachers and among the teachers and their head teachers.

Two local research assistants were recruited because the field researcher did not speak the local languages (Chiyao and Chichewa). They facilitated focus-group discussions with parents and transcribed and translated data. Focus-group questions were translated beforehand by an organisation specialising in translation and were validated by an independent and experienced local researcher. Before beginning the research, the field researcher conducted training sessions with the facilitators, which addressed research ethics, focus-group questions, the importance of note-taking and transcribing of data, and the reasoning for the debriefing sessions after each day in the field. Both facilitators originated from the Mangochi district; through this work, they acquired in-depth information on primary education in their home region. At the end of each focus-group discussion and interview, participants were invited to ask questions related directly to the research or about education in general.

The social and economic context of this study was complicated. The population of the Mangochi district is not homogenous, with the dominant religion being Islam (72%), followed by Christianity (26%) (National Statistical Office, 2019). However, the ethnicity element is beyond the scope of this study since the history of Malawi is complicated and would require a separate study.

Limitations

With this study we examined how 19 parents in four rural primary schools in one district in Malawi participated in their children's education. These parents and six teachers at each school were identified by their respective head teachers. It is important to note that they may not represent the entire set of parents at these four schools. Therefore, findings are not generalised but may give insight into how the schools in the study and other schools with similar characteristics might focus on strengthening school-home connections.

Key Findings and Discussion

In this section, research findings are presented and illustrated with direct quotes from participants. Home-setting influences were first identified in parents' perceptions of education, and reading and homework. Thereafter, school-setting influences were identified in parent-teacher communication.

Parents' Perceptions of Education The parents participating in this study expressed belief in the importance of education, talked to their children about its value, and encouraged them to attend school. They also stated that education would improve their children's chances for a better future and becoming self-reliant:

It is very important for them to become leaders of tomorrow (PFG Lakeview).

It is important because when educated, they can be employed and rely on themselves. Parents can rely on them as well (PFG Chambo).

Parents reported that they wanted their children to become educated, noting that with education comes employment, enabling their children to become self-reliant and equipping them to support their parents. Some parents stated that people in the villages were more positive regarding education today: "Compared to the past, we were behind in education, but now children understand" (PFG Lakeview).

Over the span of just a few years, at the time of the study, enrolment had increased significantly, with many children attending school with their parents' encouragement. According to parents, this indicates the shift in attitude towards education in the communities: "In those days, children were not coming in large numbers, but now there are more learners, and this shows they are feeling OK about education" (PFG Baobab).

Parents also mentioned local role models in their communities such as teachers, nurses, or others with successful careers. Parents expressed their pleasure at this progress and discussed how such role models positively affected their children's education:

We can see a change in education because some of our children have their own living examples in the community, whereby others are teachers and nurses (PFG Hillside).

Now we are happy that most government departments are also full of educated ladies from Mangochi (PFG Hillside).

Research indicates that a role model positively affects adolescents' school outcomes and youth resilience (Hurd & Zimmerman, 2011; Hurd, Zimmerman & Xue, 2009).

On the other hand, teachers and head teachers in this study generally agreed that neither parents nor the community considered education as important or valued its benefits. One teacher remarked: "The community somehow fails to understand what teachers want a child to learn" (T1 Lakeview). According to the teachers, the parents did not help them by encouraging children to attend school. Learners' lack of punctuality and frequent absences also attested to a negative attitude towards education: "[b]ut the problem is we do not have the support from the community to encourage learners to come to school frequently" (HT Hillside). School-community partnerships are important for students' academic achievement (Epstein, 2011:313). With changing attitudes and more school-community involvement, communities can adopt a sense of ownership about their schools. This may, in turn, make parents more involved in the school and their children's learning, thereby reinforcing positive attitudes towards education.

Reading and Homework

Parents reported encouraging their children to read books, and some described noticing the benefits in their children's reading and comprehension abilities as illustrated in the two excerpts below:

My Standard 2 [child] had difficulty reading to the extent that the teacher wrote me a letter, then sent me a Standard 2 textbook so that I can read it with him. This term, there is improvement because he can read. (PFG Chambo).

Yes, the child is happy because he tells me to help where he is having problems (PFG Baobab).

In their longitudinal study, Dearing et al. (2006) show that parental involvement positively affected literacy development and may have long-lasting effects on children's prospects. Similarly, Sénéchal and Young (2008) established through their meta-analytical review that parental involvement was crucial in children's literacy acquisition and development. However, parents in Malawi are faced with some challenges in this regard due to the lack of books in the homes: "Sometimes we do [read together], and sometimes we don't. Most of the time, teachers advise learners to read the books while at school" (PFG Chambo).

Parents reported that they reminded their children to do their homework and assisted if needed: "I encourage them when they come home so that this will help them in future" (PFG Baobab). Parents were positive about homework and were willing to monitor their children's homework. However, some parents complained that "teachers are not giving them homework" (PFG Chambo).

Contrary to the parents' views on homework and its importance, teachers appeared to find it futile to send homework home with the learners due to parents' lack of interest in school-related matters or their illiteracy. A teacher and a head teacher respectively noted as follows:

Most of the parents do not know how to read or write, so you can't send the learner home with homework (T5 Chambo).

Of course, I think no one is monitoring that at home; they just leave them to do whatever they want (HT Chambo).

The three main reasons why parents become involved with their children's homework are: they think their children or their children's teachers want them to be involved; they believe their involvement has a positive effect on their children's learning; and they think they should be involved (Hoover-Dempsey, Battiato, Walker, Reed, DeJong & Jones, 2001). According to this, it may be surmised that parents' views on the importance of education, as has been demonstrated in this study, play a role in their involvement with their children's homework. However, children in these schools rarely have homework, mainly due to the teachers' perception that parents were apathetic and illiterate. This is interesting since homework can be a compelling instrument for parents. For instance, they gain knowledge about the subject matter that their children are learning at school. This creates an opportunity for conversation between parents and their children on school-related matters and provides teachers and parents with an avenue to discuss education (Walker, Hoover-Dempsey, Whetsel & Green, 2004).

Parent-Teacher Communication Parents generally agreed that when their children experienced problems at school, whether behavioural or educational, the teachers would contact them and inform them of the situation: "If a child is a problem, we come and discuss, and we do this for the betterment of the child" (PFG Baobab). On the other hand, when asked whether the school contacted them when their child did well at school, parents mentioned that the school was less forthcoming: "No, we just hear during terminal examinations results" (PFG Chambo).

Teachers and head teachers agreed that they contacted parents if learners had problems at school. Most parents appreciated being kept informed: "Yes, they are happy, and they insist that I have to call them. So we do that, we call the parents, and we sit down and discuss. Then we solve the issue" (HT Lakeview).

However, according to a teacher at Hillside, not all parents were interested or grateful when contacted but would instead tell the teachers to deal with the issue themselves, as it was their job: "Some of the parents, they say it is up to you teachers to deal with the learners so that it can change" (T5 Hillside). Nevertheless, most parents were willing to work with the school to address issues that their children may be experiencing.

Learners' absenteeism was a problem in many of the schools, and several parents stated that they visited the school regularly to either observe attendance and progress or to encourage their children:

I want to know their performance and how they behave in class. To be assured, he really comes to school (PFG Hillside).

I visit school to encourage my children about

school (PFG Baobab). Parents agreed that they felt welcome at school and that teachers and head teachers encouraged them to visit to observe their child's performance in class and to attend events at school:

Yes, they want us to [visit], just because they tell us some problems concerning learners (PFG Chambo).

Yes, I do [visit], and I can remember there was a particular meeting where he [the head teacher] advised us to visit this school so we can also know the performance of our children (PFG Hillside).

This was in accordance with teachers' and head teachers' statements that they invited parents to come to school to observe their children, and they agreed on the importance of parents visiting the school: "Yes, that is indeed important, we need to be working hand in hand with them for the betterment of the learners" (T2 Chambo).

Teachers also felt motivated when parents came to school: "We are encouraged by seeing the parents coming to school asking about the performance of their child" (T3 Baobab).

Teachers and parents appeared to agree that parents were not only invited to come to school to discuss their child's behaviour but also to observe their child' s progress in school. Nevertheless, teachers generally agreed that parents did not visit the schools on their own initiative, except on rare occasions, and "those people are the ones that went to school" (T5 Hillside) and were educated themselves. Similar findings in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal, and Uganda in 2008 show that parents generally did not visit schools unless to discuss disciplinary actions (Marphatia et al., 2010). Likewise, a study conducted in South Africa concluded that parents found the schools lacking in informing them of their child's achievement, only communicating with them if their child experienced some problems at school (Meier & Lemmer, 2015).

If parents are mainly requested to visit the school when their child is experiencing problems, it may hinder parental involvement. Parents may become unwilling to enter the school to avoid receiving more negative news about their child's behaviour (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). This emphasises the importance for schools to approach parents in more favourable circumstances, for example, by informing them when their children are doing well academically or their attendance and behaviour are commendable. Such strategic communication can act as positive reinforcement for healthy parent-teacher communication. Nevertheless, parents need to be receptive to these invitations and visit the school for such communication to occur.

Conclusion and Implications

This interview-based qualitative study provided insights into parental involvement in four rural primary schools in Malawi, investigating mainly two social systems, the microsystem and the mesosystem. With this study we sought to understand how parents connected with four primary schools, participated in their child's education and how the schools involved individual parents. We found that parents appeared to be active in the home setting. However, parents and teachers expressed different views on parental involvement.

The strongest positive relationship between parental involvement and academic achievement is "academic socialisation", which is characterised by parents communicating to their children the value of education, their expectations for their achievement, and their future aspirations (Hill & Tyson, 2009). From this study, it may be argued that academic socialisation does occur in the microsystem represented by the home setting. Even though performance data were not collected in this study, the academic socialisation observed here is likely to affect academic achievement positively. The schools acknowledged the importance of communicating with parents and tried to involve them by inviting them to come to school, for example, to observe their child's progress. A summary of the main findings in the micro- and mesosystem levels is depicted in Figure 2.

In this study we found limited mesosystemic interaction. Humans develop through reciprocal interactions and relationships within the community and broader society (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The microsystem appears to be active, however, the mesosystemic interaction was limited, with miscommunication between teachers and parents. Teachers said that they hardly ever met parents, however, parents reported visiting the school regularly. It was evident that teachers expected more involvement from parents, but parents already considered themselves involved. This disparity in their reporting was compelling but not atypical. In a study by Dauber and Epstein (2011:213), teachers stated that parents were not involved in their children's education, whereas parents reported that they were involved. Such contrasting perspectives exposed how parents and teachers interpreted each other's views differently, and the difference needs to be acknowledged and addressed to support learning to a greater extent.

Exosystemic factors, such as the lack of official disapproval of parents who do not send their children to school, may influence parental involvement and learners' educational outcomes. Another exosystemic factor is the parents' education level. The parents' belief in their own knowledge may determine whether they will participate in their children's education (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). The low literacy rate in the Mangochi district of 53% (National Statistical Office, 2019) indicates a low level of education among rural parents, which may negatively affect their involvement in their children' s education. However, according to parents in the study, their communities were beginning to value education more. Finally, macrosystemic factors such as the national shortage of qualified teachers and school reading materials may negatively affect educational outcomes.

The importance of education for socioeconomic development is globally acknowledged. Numerous research studies have established that parental involvement is an important factor in academic achievement (e.g., Dahie et al., 2018; Lumadi, 2019). Parents and teachers in the four rural primary schools need to strengthen their mutual relationship to better support learners at the micro- and mesosystem levels. They could engage in more deliberate communication and collaboration to create a more conducive mesosystem for learning. For example, teachers could contact parents to inform them of their children's good behaviour and academic progress instead of mainly contacting when problems occur. Such communication opens up opportunities for positive reinforcement and parental involvement. Teachers can send learners home with homework to give parents an added opportunity to stay involved; homework also offers teachers and parents a common ground to discuss education. The school can invite parents to learner-led conferences, where the learners showcase their school work. The school can use many such occasions to get parents more involved. However, there will be exosystemic and macrosystemic challenges which impact individuals even though they do not have an active role within that system.

To further expand our understanding of parental involvement, it may be advisable to explore the disparity between how parents and teachers view parental involvement in Malawi. In our view, it would also be valuable to examine whether there is a direct positive link between parental involvement and children's academic outcomes in rural Malawi.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank all participants for their contribution to this study. I am forever grateful to them; this study would not have materialised without them. I also want to thank my two research assistants; their help was invaluable, and their presence made the fieldwork more enjoyable. Moreover, I am indebted to the specialist who verified and validated all translations. Finally, I want to thank the people of the Mangochi district for their kindness and generosity with their time to assist me and give me directions while trying to find my way to the schools during fieldwork (GE).

Authors' Contributions

GE gathered all the data, conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript. GE also created all tables and images. SRJ, AM and PM consulted on all stages of writing and gave advice and suggested changes to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 25 November 2020; Revised: 5 July 2021; Accepted: 14 October 2021; Published: 31 August 2022.

References

Bertolini K, Stremmel A & Thorngren J 2012. Student achievement factors. Brookings, SD: South Dakota State University. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308995147_Student_Achievement_Factors. Accessed 28 March 2020. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2013. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1979. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Chimombo JPG 2005. Quantity versus quality in education: Case studies in Malawi. International Review of Education, 51:155-172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-005-1842-8 [ Links ]

Clarke V & Braun V 2017. Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3):297-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dahie AM, Mohamed AA & Mohamed RA 2018. The role of parental involvement in student academic achievement: Empirical study from secondary schools in Mogadishu-Somalia. International Research Journal of Human Resources and Social Sciences, 5(7):1-24. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abdulkadir-Dahie/publication/326957190_THE_ROLE_OF_PARENTAL_INVOLVEMENT_IN_STUDENT_ACADEMIC_ACHIEVEMENT_EMPIRICAL_STUDY_FROM_SECONDARY_SCHOOLS_IN_MOGADISHU-SOMALIA/links/5b6d9f4945851546c9fa298f/THE-ROLE-OF-PARENTAL-INVOLVEMENT-IN-STUDENT-ACADEMIC-ACHIEVEMENT-EMPIRICAL-STUDY-FROM-SECONDARY-SCHOOLS-IN-MOGADISHU-SOMALIA.pdf. Accessed 26 October 2019. [ Links ]

Dauber SL & Epstein JL 2011. Parents' attitudes and practices of involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. In JL Epstein (ed). School, family and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Dearing E, Kreider H, Simpkins S & Weiss HB 2006. Family involvement in school and low-income children' s literacy: Longitudinal associations between and within families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4):653-664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98A653 [ Links ]

Desforges C & Abouchaar A 2003. The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievements and adjustment: A literature review (Research Report RR433). London, England: Department for Education and Skills. Available at https://www.nationalnumeracy.org.uk/sites/default/ files/the_impact_ofj>arental_involvement.pdf. Accessed 8 March 2020. [ Links ]

El Nokali NE, Bachman HJ & Votruba-Drzal E 2010. Parent involvement and children's academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3):988-1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x [ Links ]

Epstein JL 2011. Sample state and district policies on school, family, and community partnership. In JL Epstein (ed). School, family and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Hill NE, Castellino DR, Lansford JE, Nowlin P, Dodge KA, Bates JE & Pettit GS 2004. Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development, 75(5):1491-1509.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x [ Links ]

Hill NE & Tyson DF 2009. Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45(3):740-763. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015362 [ Links ]

Hoover-Dempsey KV, Battiato AC, Walker JMT, Reed RP, DeJong JM & Jones KP 2001. Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36(3):195-209. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5 [ Links ]

Hoover-Dempsey KV, Walker JMT, Sandler HM, Whetsel D, Green CL, Wilkins AS & Closson K 2005. Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2):105-130. https://doi.org/10.1086/499194 [ Links ]

Hornby G & Lafaele R 2011. Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1):37-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2010.488049 [ Links ]

Hurd NM & Zimmerman MA 2011. Role models. In RJR Levesque (ed). Encyclopedia of adolescence. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2 [ Links ]

Hurd NM, Zimmerman MA & Xue Y 2009. Negative adult influences and the protective effects of role models: A study with urban adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38:777-789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9296-5 [ Links ]

Johnson ES 2008. Ecological systems and complexity theory: Toward an alternative model of accountability in education. Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education, 5(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.29173/cmplct8777 [ Links ]

Jónsdóttir SR 2012. The location of innovation education in Icelandic compulsory schools. PhD thesis. Reykjavik, Iceland: University of Iceland. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1946/10748. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Lewthwaite B 2006. Constraints and contributors to becoming a science teacher-leader. Science Education, 90(2):331-347. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20093 [ Links ]

Lumadi RI 2019. Taming the tide of achievement gap by managing parental role in learner discipline. South African Journal of Education, 39(Suppl. 1):Art.#1707, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1707 [ Links ]

Madge C 1997. The ethics of research in the third world. In E Robson & K Willis (eds). Postgraduate fieldwork in developing areas: A rough guide (2nd ed). London, England: Developing Areas Research Group of the Royal Geographical Society. [ Links ]

Marphatia AA, Edge K, Legault E & Archer D 2010. Politics of participation: Parental support for children's learning and school governance in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda. Johannesburg, South Africa: Institute of Education. Available at https://actionaid.org/publications/2010/politics-participation-parental-support-childrens-learning-and-school-governance. Accessed 4 August 2018. [ Links ]

Meier C & Lemmer E 2015. What do parents really want? Parents' perceptions of their children's schooling. South African Journal of Education, 35(2):Art. # 1073, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n2a1073 [ Links ]

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 2016. Malawi education statistics 2015/16. Malawi: Education Management Information System (EMIS). [ Links ]

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 2018. Malawi Education Statistics 2017/18. Available at https://docplayer.net/223852293-Malawi-education-statistics-2017-18.html#download_tab_content. Accessed 18 April 2020. [ Links ]

Mzuza MK, Yudong Y & Kapute F 2014. Analysis of factors causing poor passing rates and high dropout rates among primary school girls in Malawi. World Journal of Education, 4(1):48-61. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v4n1p48 [ Links ]

National Statistical Office 2019. 2018 Malawi population and housing census (Main Report). Zomba, Malawi: Author. Available at https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resourcepdf/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report%20%281%29.pdf Accessed 18 April 2020. [ Links ]

Seginer R 2006. Parents' educational involvement: A developmental ecology perspective. Parenting: Science and Practice, 6(1):1 -48. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327922par0601 _1 [ Links ]

Sen A 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sénéchal M & Young L 2008. The effect of family literacy interventions on children's acquisition of reading from Kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 78(4):880-907. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308320319 [ Links ]

Uludag A 2008. Elementary preservice teachers' opinions about parental involvement in elementary children's education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(3):807-817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.009 [ Links ]

United Nations 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, NY: Author. Available at https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. Accessed 16 July 2021. [ Links ]

United Nations 2018. Sustainable development goals. Available at https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/. Accessed 5 September 2020. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme 2018. Human development indices and indicators 2018 statistical update. New York, NY: Author. Available at http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2020. [ Links ]

UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2017. More than one-half of children and adolescents are not learning worldwide (Fact Sheet No. 46). Available at http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs46-more-than-half-children-not-learning-en-2017.pdf. Accessed 11 January 2020. [ Links ]

Walker JMT, Hoover-Dempsey KV, Whetsel DR & Green CL 2004. Parental involvement in homework: A review of current research and its implications for teachers, after school program staff, and parent leaders. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project, Harvard Graduate School of Education. Available at https://inside.sou.edu/assets/ed-health/education/docs/ecd/ParentInvolveHomework.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2020. [ Links ]

Wang MT & Sheikh-Khalil S 2014. Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85(2):610-625. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12153 [ Links ]

Wei F & Ni Y 2023. Parent councils, parent involvement, and parent satisfaction: Evidence from rural schools in China. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(1):198-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220968166 [ Links ]

World Bank 2018. Facing forward: Schooling for learning in Africa. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/facing-forward-schooling-for-learning-in-africa. Accessed 25 January 2020. [ Links ]