Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 no.3 Pretoria Ago. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n3a2093

ARTICLES

Investigating the beliefs and attitudes of teachers towards students who stutter

Abdulaziz Almudhi

Department of Medical Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia and Speech Pathology Research Unit, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia. almudhi@kku.edu.sa

ABSTRACT

With the study reported on here we aimed to investigate teachers' beliefs and attitudes towards students who stutter. These aspects were investigated through a questionnaire developed for the study. A total of 382 Saudi teachers from public and private schools from different educational levels were included in this questionnaire-based study. The results show that most respondents believed that there was a high prevalence of stuttering in the general population. Male teachers had a better understanding of persons who stutter (PWS) than female teachers. Senior teachers had better insight into stuttering. The teachers commonly had a positive opinion of PWS. Participants reported that few sources on education about and experiences with PWS were available to them. The results confirm that the teachers had reasonably good knowledge about stuttering. The results show that the teachers knew about stuttering, that they also knew about the consequences of stuttering and the way in which these children should be treated in class. The teachers possessed knowledge and had a positive attitude towards children who stutter (CWS). The findings show a change in perspectives towards CWS as a positive impact of the media.

Keywords: attitudes; beliefs; persons who stutter; stuttering; teacher

Introduction

Stuttering is a fluency disorder characterised by frequent disruption which may include repetitions (phonemes, syllables, or words), prolongations and blocks (Guitar, 2006). Stuttering is assumed to be seen in 5% of the total population (Davis, Howell & Cooke, 2002). According to published evidence (Adriaensen & Struyf, 2016), the incidence is assumed to reach a cumulative rate of 8% by the age of 3 years, while it is assumed to reach 11% by the age of 4. According to the data from the centres for disease control and prevention, the prevalence rate is assumed to be around 1.6% for children between 3 and 17 years of age (Turnbull, 2006). The relative prevalence rating derived by comparing the prevalence rates in children between 3 and 10 years and 11 and 17 years suggests that the incidence would be more in the former than the latter.

The symptoms of stuttering can be divided into overt and covert symptoms. Overt symptoms are the visible ones: repetitions, prolongations, pauses, blocks and are classified under the overt category. The secondary behaviour seen in persons who stutter (PWS) can also be classified under the overt category owing to the visibility of symptoms. While symptoms like anxiety, anticipation and hesitation are primarily categorised under the covert category, feelings of guilt, shame, inferiority, underestimation, et cetera also belong to this category.

Stuttering is usually identified and diagnosed by virtue of the overt symptoms. The covert symptoms receive relatively less attention than overt symptoms. The covert symptoms are highly individualistic and vary among PWS. Many questionnaires have been designed to investigate covert symptoms in PWS. Stuttering is regarded as an elusive condition due to its combination of overt and covert characteristics. The identification of the covert symptoms is essential in children and adolescents. These symptoms in children would hamper the development of interpersonal relationships (Fogle, 2012). Covert symptoms can also impact how these children approach adulthood, as it may have a negative influence on their mental health.

Related Work

Impact of stuttering in children

Children exhibiting stuttering may initially not be aware of their condition but may eventually become conscious of the problem. Children who stutter may be subjected to bullying - a global phenomenon (Winnaar, Arends & Beku, 2018) - and teasing (Mooney & Smith, 1995). Greene, Robles, Stout and Suvilaakso (2013) report that approximately 246 million individuals are annually exposed to some form of bullying. Bullying is considered as one of the most common reactions by peers towards CWS. Bullying, especially in the school setting, has been a common problem and has been prevalent for many years, although the problem has not been considered to be significant until recent years. Even though experts believe that most people underestimate the prevalence of bullying, studies indicate that 30 to 60% of children have been victimised during their school years (Glover, Gough, Johnson & Cartwright, 2000; Rigby, 2000; Smith & Shu, 2000).

According to a study by Berger in 2007, bullying can be classified intro three types - physical bullying, behavioural bullying and verbal bullying. Physical bullying involves physical harm being directed at another person; behavioural bullying involves a malicious act towards another person, developing a negative attitude towards the person, and so on; verbal bullying involves abuse towards and putting the person down. Bullying by peers has shown to be a common global occurrence among school-going children and adolescents. Teachers would be in a position to play a major role in regulating the behaviour of peers towards children who stutter, thus preventing bullying (Allen, 2010; Merrett & Wheldall, 1993; Stoughton, 2007). To handle such situations at school, teachers are assumed to have good knowledge about the impact of stuttering.

Role of teachers

The role of teachers has been changing with time (Balyer & Ozcan, 2020). Teachers not only play an important role in supporting the optimal educational development of CWS, but also in preparing these children to confront the challenges they will experiences during the course of their education and future employment. To handle CWS, teachers are expected to have good knowledge about stuttering. In addition to this, teachers are also expected to have a positive attitude towards CWS. The next section of this article deals with the review of studies on the attitudes and beliefs of teachers towards CWS.

The attitudes of teachers towards CWS

The perceptions that teachers and others have towards PWS are likely to have an impact on how PWS view themselves. Teachers' attitudes play a very important role when it comes to the attitudes of school-going CWS. In addition to teachers' attitudes, the attitude of peers also would have an impact on the covert behaviour exhibited by CWS (Jenkins, 2010).

Many studies have been done based on the attitudes and beliefs of teachers/educators on CWS. The majority of research, unfortunately, has indicated that educators and peers are likely to have negative perceptions or associate negative personality traits towards CWS (Cooper & Cooper, 1996; Dorsey & Guenther, 2000; Lass, Ruscello, Pannbacker, Schmitt, Kiser, Mussa & Lockhart, 1992; Thatcher, Fletcher & Decker, 2008).

The educators are found to have reported that the CWS are anxious, shy, withdrawn, self-conscious, tense, less competent, hesitant and insecure. The findings of some studies on the other side of the spectrum are also reported - Irani and Gabel (2008) report fewer negative findings in comparison with previous studies. The educators considered in this study believed that stuttering and intelligence were two different issues that may not impact each other. Thus, in summary, studies report positive and negative behaviours exhibited by educators towards CWS, with more studies leaning toward the latter. The next section deals with specific studies on the attitudes and beliefs that teachers exhibit towards CWS. Studies carried out in the current decade in different parts of the world are reviewed here.

Teachers' perceptions of the problems with CWS were compared in Rio de Janeiro and Salvador (Fonseca & Nunes, 2013). Teachers in Rio de Janeiro possessed greater knowledge, and this was attributed to the higher educational level, however, the difference was not statistically significant. The performance of the participants varied as a function of education level. This statement applied more to the participants at Salvador. Seventy-six point three per cent of respondents were of the opinion that CWS should consult speech-language pathologists (SLP) while 53.4% of respondents with an elementary school education felt that CWS should be referred to the family physician. In Salvador, 1.4% of the participants said that they would seek help from a speech therapist and a physician. In Rio de Janeiro, none of the participants reported an association of responses. With the same research question used in Shanghai, the vast majority of respondents reported that they would consult a speech and language therapist, although there was no regulated profession that addresses this issue (Gabel, Blood, Tellis & Althouse, 2004).

The awareness and attitudes of teachers towards the primary school CWS were investigated in India by employing a questionnaire (Silva, Martins-Reis, Maciel, Ribeiro, De Souza & Chaves, 2016). The questionnaire was developed as a part of the study and had three sections on awareness, attitude and teachers' perceptions. The participants were recruited through convenience sampling. Seventy primary school teachers were considered. The results indicated that the questions pertaining to the teachers' awareness towards stuttering received an average score of 63.16%. The attitude score for the teachers was 55.7% and a score of 48.5% for the teacher's perception regarding the students' interaction with the CWS was obtained. The authors concluded that the teachers were aware of the development of speech and language patterns, the errors which would be exhibited during the developmental period; this enabled them to differentiate stuttering from normal non-fluency. The teachers had a considerable amount of knowledge about stuttering.

Teachers' attitude and beliefs towards CWS were investigated through another study in India by Pachigara, Stansfielda and Goldbarta in 2011. The teachers' attitudes towards CWS was investigated using questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with 58 teachers. Results from the questionnaire show that the teachers believed that the child's environment played a significant role in shaping their behaviour. The findings also show that some of these teachers had less exposure to stuttering; at the same time they were of the opinion that they would do justice to CWS if confronted by them in future.

The teachers did not believe that CWS were shy and withdrawn. The study also targeted children with dyslexia and the teachers were of the opinion that dyslexia was more important than stuttering in the school setup.

Along the same lines, Kumar and Varghese (2018) carried out a study with the aim of assessing the awareness and attitudes of teachers towards CWS. A total of 70 primary school teachers were considered for the study aiming to assess the teachers' awareness and attitudes. The teachers were recruited through convenience sampling. A questionnaire, which was developed exclusively for the study, was used for data collection. The findings of the study show that teachers were aware of the development of speech and language patterns and were able to identify stuttering as well as differentiate stuttering with normal non-fluency. They were in a position to make appropriate referrals when needed. The limitation of the study was that it did not investigate the negative and positive behaviour of teachers towards CWS.

In some studies norm-referenced questionnaires were used to determine the behaviour and attitudes of teachers. A common questionnaire may help in drawing generalisations. The International Project on Attitudes Toward Human Attributes developed the Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes-Stuttering (POSHA-S), designed to measure worldwide public opinion and attitudes towards stuttering (St Louis, 2014). The questionnaire was modified to suit the stuttering population. The questionnaire contains two sections - one focusing on obtaining details about self-awareness and the other to obtain details about beliefs and attitudes.

Abrahams, Harthy, St Louis, Thabane and Kathard (2016) studied teachers' attitudes towards CWS in South Africa. The study had two objectives: the primary objective was to explore the attitudes of teachers and the secondary aim was to compare these responses to the respondents' data saved in POSHA-S's database. A cluster sample of 469 participants was chosen as participants. Overall positive attitudes towards stuttering were found -specifically related to the potential of people who stutter, while some teachers still held misconceptions about personality stereotypes and the cause of stuttering. The attitudes of the South African sample were slightly more positive compared to the samples in the current POSHA-S database.

The POSHA-S study was initially carried out in Kuwait (Abdalla & St. Louis, 2012). The study investigated schoolteachers' attitudes toward stuttering. Two hundred and sixty-two Arabic-speaking residents of Kuwait served as participants. The results of the study show that teachers were familiar with the concept of stuttering, however, they held misconceptions about the cause of stuttering and were biased by personality stereotypes, role entrapment (i.e. cannot do any job they want) and strategies for coping with stuttering (i.e. repetition).

The same authors carried out another study in 2014 in which they investigated the attitudes of teacher trainees and teachers towards CWS and the impact of a documentary on their attitudes and behaviour. The study was also carried out in Kuwait, where Arabic was the participants' mother tongue. Of these participants, 50% were recruited as a control group while the other 50% were recruited to the experimental group. The results of the study show that the behaviour and attitudes of the pre-service trainees and teachers were initially predominantly negative, but these changed once they had viewed a documentary on stuttering.

Similarly, Arnold, Li and Goltl (2015) used the POSHA-S beliefs sub-score to compare the scores of 269 kindergarten to Grade 12 teachers with 1,388 non-teachers from the POSHA-S database. Linear regression analysis indicated that there were no differences between teachers and non-teachers. Nevertheless, irrespective of profession, female participants provided statistically significant (p < 0.001) more accurate beliefs. An increase in age (p < 0.01) and years of education (p < 0.01) were significantly associated with more favourable beliefs. Participants who knew at least one person who stuttered were found to have more positive responses (p < 0.01).

Furthermore, Li and Arnold (2015) also considered the self-reactions sub-score. The results indicate no significant difference in any of the components forming the self-reactions sub-score, except knowledge source. Teachers generally scored higher than non-teachers, indicating a larger variety of sources of knowledge. Age (p < 0.001) and years of experience (p < 0.001) were also associated with more positive responses. Regardless of occupation, it was found that female participants generally scored higher than male participants for the accommodating and/or helping component (p < 0.001).

Researchers have pointed out that there is no flexibility in the POSHA-S questioner, as it does not allow addition and deflection of questions. Furthermore, it specifies that the study must be carried out by using a standard set of questions. It should also be noted that no previous studies have been conducted on stuttering in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the aim of this study was, using a survey questionnaire, to investigate Saudi teachers' beliefs and attitudes towards students who stutter in the Saudi population. We also investigated the impact of variables like education and experience on the teachers' awareness of stuttering.

Methods

We used a questionnaire research design in this study. Questionnaire research can provide in-depth knowledge on any topic (Creswell, 2012; Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Marshall & Rossman, 2006) and can be used for describing, analysing, and interpreting common behaviour patterns and beliefs that developed over time among teachers sharing the same culture. However, many studies have reported similar findings in different countries. But cross-cultural variations (St Louis, 2014) may have a small but significant effect on the attitudes in a given context. Hence the present study is apt in this given context.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the College of Applied Medical Sciences (CAMS 0023738), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Study Participants

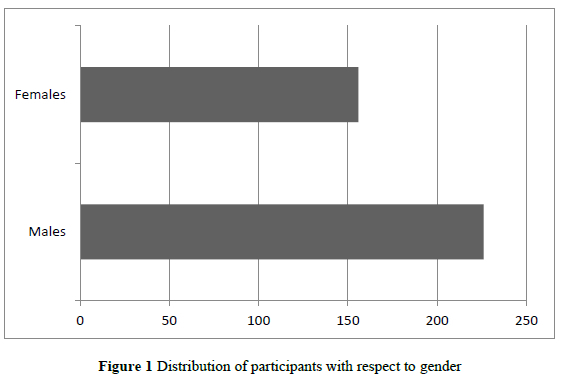

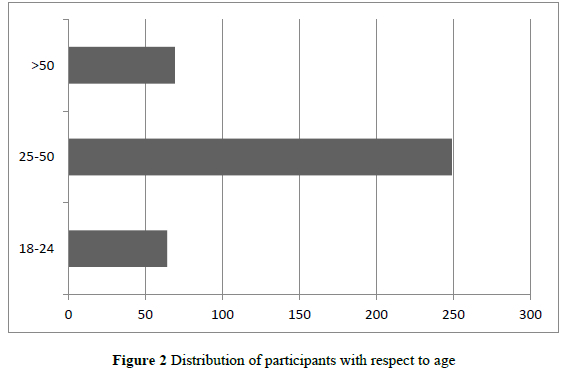

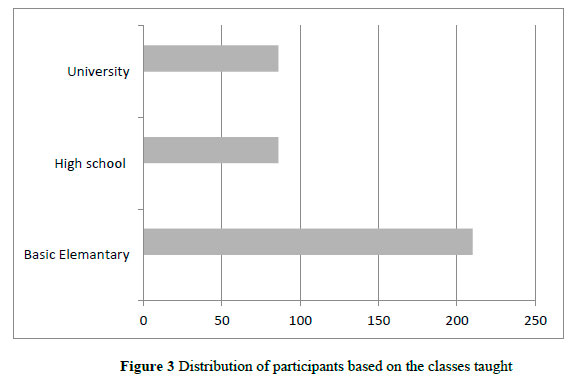

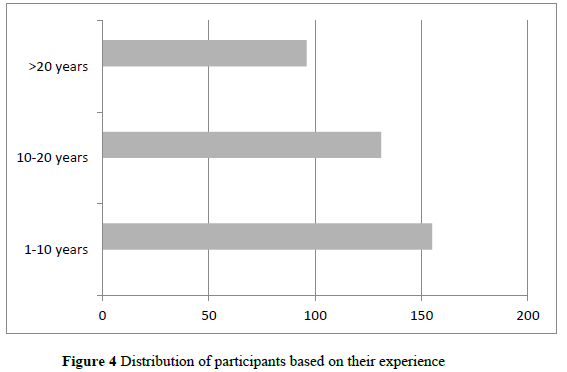

A total of 382 teachers (226 male and 156 female) participated in this study and all of them were recruited from public and private schools in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. The teachers ranged in age between 22 and 50 years. The teachers' teaching experience ranged from 1 to 30 years and the teachers taught at primary, elementary, and high schools. The number of teachers in each of these categories is indicated in the results section (Table 1). Stratified random selection was used to select the participants. In this study, the participants were divided into clusters based on the educational level of the students taught and the participants were randomly selected from these schools. Equal representation was taken from schools in different parts of Riyadh (north, south, centre, west and east). The samples of primary, secondary and high school teachers were selected from both private and public schools: (private primary school teachers n = 37 and public primary school teachers n = 107); (private secondary school teachers n = 18 and public secondary school teachers n = 87;) (private high school teachers n = 10 and public secondary school teachers n = 126). Participants within the schools were selected according to random selection.

Questionnaire

The teachers' beliefs and knowledge about stuttering were tested using the Arabic version of the POSHA-S questionnaire developed by Abdalla and St. Louis (2012). The same is provided in Appendix A.

Quality check and feedback analysis The questionnaire was circulated to two native experts and their feedback and opinions were incorporated in improving the quality of the questionnaire. The modified changes were structural modifications, font changes and shortening of the questions. Once the changes had been incorporated, the final version of the questionnaire was administered to the participants (teachers).

Results

In this study we focussed on investigating the beliefs and attitudes of teachers towards CWS. The study was carried out with 382 participants in Saudi Arabia. The participants were asked to complete a questionnaire. The questions elicited details about the teachers' beliefs and attitudes. A comparison was done based on the teachers' age, gender and experience. The association between age and gender with beliefs and attitudes was verified by employing a chi-square test.

The first part of the results focus on the distribution of the participants based on age, gender, level of experiences and classes taught. The details of the distribution are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1 indicates that the number of male participants were more than female participants (ratio of 60:40). Figure 2 indicates that most participants were between 25 and 50 years old (65%), followed by participants who were older than 50 years (18%). Fewer participants were between 18 and 24 years (16%) old. Table 1 also provides details regarding the distribution of the participants based on the classes that they taught. The majority of participants taught at basic or elementary school (55%) followed by high school (22.5%) and university (22.5%). The distribution with regard to experience reveals that the greater number of participants had between 1 and 10 years' teaching experience. About 35% of the participants had between 11 and 20 years' experience with about 25% of the participants who had more than 20 years' experience. The teachers were required to answer Yes or No to the questions on their beliefs.

Table 2 indicates that most teachers claimed that they had the ability to understand PWS (82.3%) and that they were of the opinion that stuttering negatively affected children (73.8%). The teachers did not agree that PWS seemed to be less mature compared to their peers who did not stutter (Yes = 24%, No = 76%). The teachers reported that most of the PWS (62.7%) sometimes participated verbally in class. As far as participation is concerned, the teachers believed that the CWS rarely participated in the class or sometimes participated in the class. The teachers noticed that PWS felt embarrassed or anxious during answering questions or interacting with peers who did not stutter (74.8%). They further indicated that PWS showed lower self-esteem as they did not trust themselves because of the stuttering (75.1%).

Table 3 shows the percentage of teachers' responses on questions about the characteristics of PWS. Most of teachers claimed that they had correct information about the characteristics of PWS; 66.6% of them responded negatively to the question implying that stuttering affected children's IQ. A great percentage of teachers (60.3%) believed that CWS were shy and calm, 62.5% believed that the CWS were different from other students while 67.6% believed that students who stuttered should learn how to accept teasing from others and thus develop coping behaviour. Eighty-three and a half per cent of teachers believed that stuttering was a problem that could be treated, while the majority of teachers (85%) agreed that the child's environment was a vital element in increasing or decreasing the stuttering.

Table 4 shows the percentage of teacher responses to questions about their reactions towards PWS. The results show that teachers had effective ways of dealing with PWS; 70.6% of the teachers indicated that PWS should not be exempt from speaking in front other students; 77.7% of the teachers indicated that one should not pay any attention to the PWS speech; 88.6% believed that good interaction increased the fluency of PWS, while 79.9% of the teachers claimed that punishment may not be apt and may adversely affect stuttering. Teachers were divided with regard to the belief that repetition improved fluency of speech, while 11.2% of teachers indicated that they had taught between 1 and 5 PWS. The results did not show any clear differences related to age, gender, educational level, sector, or teacher experience.

Table 5 shows the percentage of teacher responses to questions about sources of information about stuttering. The teachers did not show any preferred source of information from which they had gained information about stuttering.

The association of the teachers' age and teaching experience with their beliefs and attitudes towards PWS was evaluated in this study. Both age (p = 0.01) and years of experience (p = 0.001) showed significant correlations with the teachers' beliefs and attitudes and their communication with PWS. Older male teachers with more than 20 years of experience showed significant positive attitudes as well as healing students with stuttering than females in the same group.

The effects of gender on frequency levels of the beliefs and attitudes of respondents (teachers) towards stuttering among Saudi students were evaluated. Based on gender specificity, it was observed that the male teachers showed more information about stuttering than female teachers (95.13% male vs 59% female; p = 0.01). Also, beliefs of the severity of stuttering, understanding the impact of stuttering on the social and personal life of PWS were significantly more among male teachers than female teachers (92% male vs 85.2% female; p = 0.01). Also, the positive reactions, understanding PWS, helping students who stutter in participating in school and class activities were significantly higher among male teachers than females (96% male vs 89.7% female; p = 0.001).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate teachers' beliefs and attitudes towards students who stutter. This was the first such study conducted in the Saudi population and the results confirm the positive involvement of teachers with regard to their knowledge of CWS. The effect of two demographic variables (age, gender) on teachers' beliefs and attitudes was investigated. It was found that male teachers had a better understanding about stuttering than female teachers. Older teachers exhibited better insight into stuttering than younger teachers. There was a positive association between both these variables and the teachers' attitudes and beliefs.

Classes taught and levels of experience were the other two demographic variables considered. It was found that teachers' attitudes and beliefs did not vary with regard to the classes that they taught and their experience. However, the association between the teachers' beliefs and attitudes with these two demographic variables were not investigated here, but will be discussed in future publications.

As far as the maturity of CWS was concerned, the teachers felt that CWS were not mature enough. With regard to the verbal participation of CWS, the teachers were of the opinion that CWS would participate verbally. When they were asked about the extent of participation, they indicated that CWS participated sometimes or never and not all the time. The participants further indicated that CWS were embarrassed when questions were asked. Furthermore, the participants indicated that CWS lacked self-trust and confidence as a result of the stuttering.

Regarding the presentation skill, the majority of teachers were of the opinion that stuttering would hamper the quality of class presentations.

Approximately 50% of teachers indicated that they would report anxiety faced by CWS to parents.

However, teachers were of opinion that CWS experienced anxiety and stuttering hampered the quality of class presentations. But teachers reported that CWS were not hesitant when speaking in front of others (a casual talk). Although these two statements seemed contradictory, informing about two different situations was evaluated. The classroom presentation is a presentation on stage, which leads to an increase in stuttering and anxiety, whereas CWS talking in front of others is a general situation. The second observation was interesting as CWS would usually be hesitant in classroom situations. In addition, teachers were asked about the classroom behaviour of CWS. It was observed that CWS were shy and withdrawn in the class in terms of their social interaction. Although CWS were shy and withdrawn, they would interact with other children and participants in general discussion in the classroom when given the opportunity.

The teachers were asked whether they would pay attention to the speech of CWS. It was revealed that a considerable number of teachers paid attention to the speech of CWS. The finding was yet again interesting as it quantified the weightage given by the teachers to the speech of PWS. The next question asked whether the participants asked the CWS to repeat the utterance(s) until their speech attained fluency. There were mixed responses to this question. Half of the participants were of the opinion that the CWS should be asked to repeat while the remaining half said that they would not repeat. In the next question participants were asked whether the teachers felt that CWS were different from the other children in the class. It was observed that some teachers were of the opinion that CWS were different from other children and a lesser proportion of the participants felt that these CWS were not atypical, but were similar to other children in class.

The next question probed details regarding the treatment of these children in class and whether this treatment would in any way increasing their fluency. Most of the teachers felt that the way children were treated would have a bearing on fluency and they felt that if children were treated well, fluency would be enhanced. In the next question the teachers were asked whether CWS should learn to accept the teasing/bullying. It was observed that the teachers felt that the children should learn to accept the teasing and bullying. The participants were asked if stuttering would increase as a consequence of punishment and it was revealed that most of the participants believed that by punishing CWS their problem would increase. This finding shows that the teachers were aware of the fact that the CWS should not be punished. The next question was about a cure for stuttering. From the findings it is clear that the participants believed that there was no cure for stuttering. In the next question the participants were asked whether they believed that the environment would have a bearing on the variability of the stuttering behaviour. Most of the teachers felt that the environment would play a major role in modulating stuttering. In other words, the participants felt that an increase or decrease in stuttering was directly dependent on the environment. The next question required the participants (teachers) to indicate the number of CWS during their years of service. The results show that almost all the teachers had seen CWS, however the number was not very significant. The next question elicited details regarding the source of information and it was revealed that the participants knew about stuttering from the published information in newspaper/magazines and information on social media.

Based on the attitudinal statements, it was in general observed that the teachers commonly had a positive opinion of students who stutter. Participants reported a few sources of information about the education of and experience with students who stutter, which may have affected the response of the teachers to the questionnaire items.

The data on prevalence indicates that stuttering is a very common problem. The data regarding onset shows that the onset of stuttering would be at its peak during the early school years. The teachers would play a vital role in handling the bullying and regulating behaviour of these children.

Many studies on the attitude and beliefs of teachers/educators on CWS have been carried out in the past. The majority of research unfortunately has indicated that educators and peers were likely to have negative perceptions or associate negative personality traits towards CWS (Cooper & Cooper, 1996; Dorsey & Guenther, 2000; Lass et al., 1992; Thatcher et al., 2008). Previous studies show that the educators reported that CWS are anxious, shy, withdrawn, self-conscious, tense, less competent, hesitant and insecure. However, some studies report exceptional findings. Some of these studies have shown that participants had considerable knowledge of PWS (Pachigara et al., 2011). One more study (Kumar & Varghese, 2018) shows that teachers also understood the role of environment. Thus, the teachers would know about the role of the environment influencing stuttering.

Our study was carried out in Saudi Arabia where there is dearth of information about the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on CWS. Although such studies have been carried out globally, there could be a cultural difference owing to which the results may vary from one country/context to another (St Louis, 2014). This necessitated our study from which it was proven that the teachers had good knowledge about stuttering, consequences of stuttering, an understanding that PWS should not be punished or teased which may have negative effects on child who stutter. The teachers also knew about the role of environment influencing stuttering. These findings are in agreement with that of an earlier study by Abrahams et al. in 2016 who report that the teachers had positive attitudes towards children with stuttering. The teachers, as in our study, held minor misconceptions about CWS.

We also studied the effect of age and gender on knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding PWS. It was found that the male teachers had a better understanding of stuttering than female teachers and senior teachers had a better understanding of stuttering than younger teachers.

In earlier studies POSHA-S was used to understand the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about CWS. In our study a questionnaire designed exclusively for the study was used.

The basic strength of this study is that it was the first study conducted in the Saudi Arabia. Another strength is that the questionnaire questions were compiled after details about the studies done in the past were collected and after reviewing the questions used in these studies. A limitation of the study was that it involved schools from only one city in Saudi Arabia. Teachers' attitudes about stuttering are important, and the improvement of healthy and helpful techniques and strategies to be used in the classroom would benefit PWS. Similar studies in other regions of the country as well as in different Arab countries are needed.

Conclusion

The study was a preliminary attempt in investigating the knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of teachers in Saudi Arabia about CWS. The results show that participants in this study held fairly good knowledge about stuttering and they believed that students who stuttered had the same IQ scores as normal students. Furthermore, the participants were of the opinion that their treatment and recovery options were easy to apply during daily school activities through direct confrontation, understanding stuttering, and prompting collaboration in academic achievements. The teachers also knew about the consequences of stuttering and the way that these children should be treated in class. The results also indicate that male teachers with more teaching experience showed a better understanding about stuttering and its consequences. The study provides evidence to understand the attitudes of teachers towards CWS in Saudi Arabia. The results can be used to present sensitisation programmes for teachers to modify their attitudes towards CWS. The results of the study can be compared with the POSHA-S database to compare the attitudes of the teachers of Saudi Arabia with the attitudes of teachers in the rest of the world.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through a Research Group Project under grant number R.G.P. 1/154/40.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abdalla FA & St. Louis KO 2012. Arab school teachers' knowledge, beliefs and reactions regarding stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 37(1):54- 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjfludis.201L1L007 [ Links ]

Abrahams K, Harty M, St Louis KO, Thabane L & Kathard H 2016. Primary school teachers' opinions and attitudes towards stuttering in two South African urban education districts. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 63(1):a157. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v63i1.157 [ Links ]

Adriaensens S & Struyf E 2016. Secondary school teachers' beliefs, attitudes, and reactions to stuttering. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 47(2):135-147. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0019 [ Links ]

Allen KP 2010. Classroom management, bullying, and teacher practices. The Professional Educator, 34(1). Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ988197.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Arnold HS, Li J & Goltl K 2015. Beliefs of teachers versus non-teachers about people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 43:28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjfludis.2014.12.001 [ Links ]

Balyer A & Ózcan K 2020. Teachers' perceptions on their awareness of social roles and efforts to perform these roles. South African Journal of Education, 40(2):Art. #1723, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n2a1723 [ Links ]

Berger KS 2007. Update on bullying at school: Science forgotten? Developmental Review, 27(1):90-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.08.002 [ Links ]

Cooper EB & Cooper CS 1996. Clinician attitudes towards stuttering: Two decades of change. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 21(2):119-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0094-730X(96)00018-6 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Davis S, Howell P & Cooke F 2002. Sociodynamic relationships between children who stutter and their non-stuttering classmates. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(7):939-947. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00093 [ Links ]

Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (eds.) 2011. The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dorsey M & Guenther RK 2000. Attitudes of professors and students toward college students who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 25(1):77-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-730X(99)00026-1 [ Links ]

Fogle PT 2012. Essentials of communication sciences & disorders. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Fonseca NTM & Nunes RTA 2013. Conhecimento sobre a gagueira na cidade de Salvador [Knowledge about stuttering in the city of Salvador]. Revista CEFAC, 15(4):884-894. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-18462013000400017 [ Links ]

Gabel RM, Blood GW, Tellis GM & Althouse MT 2004. Measuring role entrapment of people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 29(1):27-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/jofludis.2003.09.002 [ Links ]

Glover D, Gough G, Johnson M & Cartwright N 2000. Bullying in 25 secondary schools: Incidence, impact and intervention. Educational Research, 42(2):141-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/001318800363782 [ Links ]

Greene ME, Robles OJ, Stout K & Suvilaakso T 2013. A girl's right to learn without fear: Working to end gender-based violence at school. Woking, England: Plan Limited. Available at https://plan-uk.org/file/plan-report-learn-without-fearpdf/download?token=HMORNNVk. Accessed 31 August 2020. [ Links ]

Guitar B 2006. Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment (3rd ed). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Irani F & Gabel R 2008. Attitudes des enseignants et des enseignantes envers les bègues : Résultats d'une enquête menée par la poste [Schoolteachers' attitudes towards people who stutter: Results of a mail survey]. Revue Canadienne D'orthophonie Et D'audiologie, 32(3):129-134. Available at https://www.cjslpa.ca/files/2008_CJSLPA_Vol_32/No_03_109-140/Irani_Gabel_CJSLPA_2008.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Jenkins H 2010. Attitudes of teachers towards dysfluency training and resources. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3):253-258. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549500903266071 [ Links ]

Kumar AS & Varghese AL 2018. A study to assess awareness and attitudes of teachers towards primary school children with stuttering in Dakshina Kannada District, India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 12(9):9-13. [ Links ]

Lass NJ, Ruscello DM, Pannbacker MD, Schmitt JF, Kiser AM, Mussa AM & Lockhart P 1994. School administrators' perceptions of people who stutter. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25(2):90-93. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461.2502.90 [ Links ]

Li J & Arnold HS 2015. Reactions of teachers versus non-teachers toward people who stutter. Journal of Communication Disorders, 56:8-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.05.003 [ Links ]

Marshall C & Rossman GB 2006. Designing qualitative research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Merrett F & Wheldall K 1993. How do teachers learn to manage classroom behaviour? A study of teachers' opinions about their initial training with special reference to classroom behaviour management. Educational Studies, 19(1):91-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569930190106 [ Links ]

Mooney S & Smith PK 1995. Bullying and the child who stammers. British Journal of Special Education, 22(1):24-27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.1995.tb00907.x [ Links ]

Pachigara V, Stansfielda J & Goldbarta J 2011. Beliefs and attitudes of primary school teachers in Mumbai, India towards children who stutter. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(3):287-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2011.598664 [ Links ]

Rigby K 2000. Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. Journal of Adolescence, 23(1):57-68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0289 [ Links ]

Silva LK, Martins-Reis VO, Maciel TM, Ribeiro JKBC, De Souza MA & Chaves FG 2016. Gagueira na escola: Efeito de um programa de formação docente em gagueira [Stuttering at school: The effect of a teacher training program on stuttering]. CoDAS, 28(3):261-268. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20162015158 [ Links ]

Smith PK & Shu S 2000. What good schools can do about bullying: Findings from a survey in English schools after a decade of research and action. Childhood, 7(2):193-212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568200007002005 [ Links ]

St Louis KO 2014. Summaries: POSHA studies. Available at http://www.stutteringattitudes.com/Side_Links/summaries.html. Accessed 11 September 2020. [ Links ]

Stoughton EH 2007. "How will I get them to behave?": Pre service teachers reflect on classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(7):1024-1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.001 [ Links ]

Thatcher KL, Fletcher K & Decker B 2008. Communication disorders in the school: Perspectives on academic and social success an introduction. Psychology in the Schools, 45(7):579-581. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20310 [ Links ]

Turnbull J 2006. Promoting greater understanding in peers of children who stammer. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 11(4):237-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750601022139 [ Links ]

Winnaar L, Arends F & Beku U 2018. Reducing bullying in schools by focusing on school climate and school socio-economic status. South African Journal of Education, 38(Suppl. 1):Art. #1596, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38ns1a1596 [ Links ]

Received: 15 July 2019

Revised: 30 June 2021

Accepted: 21 June 2021

Published: 31 August 2022

Appendix A

Questionnaire: Investigating the Beliefs and Attitudes of Teachers towards Students who Stutter

Please answer all questions in this questionnaire. Put a circle on the appropriate answer. Your answers will be confidential and only available to the researcher. Bear in mind that answering this questionnaire will take up to 10 minutes of your time. Your help is appreciated and respected.