Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 no.3 Pretoria Ago. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n3a2061

ARTICLES

A journey to adolescent flourishing: Exploring psychosocial outcomes of outdoor adventure education

Judith Blaine; Jacqui Akhurst

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa j.blaine@ru.ac.za, judyblaine19@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

There is an increasing appreciation that, in order to prepare learners for success in life, they require a holistic education providing not only academic skills, but also psychosocial competencies (Zins & Elias, 2006). Outdoor adventure education (OAE) shows potential as a way of developing these life skills, which are not easy to incorporate into the school curriculum (Sibthorp & Jostad, 2014). The aim of this qualitative study was to explore the psychosocial outcomes and perceived value of a school-based OAE programme (Journey) for adolescents in South Africa. Data from a convenience sample of 144 Grade 10 learners' post-Journey surveys, letters to the school principals and interviews with members of the focus groups (n = 20), were thematically analysed using template analysis. Applying the acronym, FLOURISHING, the analysis suggests that while Journey was beneficial for the psychosocial development of most learners, not all perceived value from their experiences. We propose that positive psychosocial outcomes could be enhanced by adopting a strength-based approach to OAE. This study provides a unique sociocultural perspective, corroborating the beneficial effects of OAE and could have implications for pedagogical policy and practice within South Africa (SA) and further afield.

Keywords: adolescent psychosocial competencies; adolescent well-being; Outdoor Adventure Education; strength-based approach

Introduction

The growth in the field of positive psychology and youth development (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) has resulted in increased understanding that holistic education, comprising basic academic skills and psychosocial competencies, is vital to prepare individuals for responsible adulthood and to thrive in life (Payton, Weissberg, Durlak., Dymnicki, Taylor, Schellinger & Pachan, 2008). Researchers have highlighted the importance of soft skills (e.g. social skills, grit, resilience and positive mindsets) to support learners' achievements, both within and away from the classroom (e.g. Richmond, Sibthorp, Gookin, Annarella & Ferri, 2018). These skills are especially essential for adolescents, navigating a progressively challenging academic workload while experiencing biological and emotional changes (Matlala, 2011). Many schools are looking for new ways to support adolescent development, with the aim of preparing our youth to survive and thrive in a capricious and changeable future (Rodkin & Ryan, 2012). Outdoor adventure education (OAE) offers promise for generating these desired outcomes, which are often difficult to achieve in a classroom (Sibthorp & Jostad, 2014).

OAE is an experiential approach to learning in which learners interact with the natural environment. For this study, OAE refers to education in, for, about and through the outdoors. This includes activities such as camping, cycling, hiking, kayaking, and running. The purposeful use of adventure, involving other people and natural resources, is thought to support the positive development of life skills as well as inter- and intrapersonal skills (Bowen, Neill & Crisp, 2016). Studies have shown that, combining elements of risk within a controlled environment, OAE not only increases learners' physical well-being, but also provides opportunities to achieve personal goals, for example, developing good interpersonal relationships (Mirkin & Middleton, 2014), enhancing resilience (Hayhurst, Hunter, Kafka & Boyes, 2015), enhancing emotional intelligence (Opper, Maree, Fletcher & Sommerville, 2014), gaining confidence (Ee & Ong, 2014), increasing life effectiveness skills (McCleod & Allen-Craig, 2007; Neill, 2002; Thomas, 2019), increasing self-efficacy (Jones & Hinton, 2007), and improving learner engagement (White, 2012).

The bulk of OAE research has taken place in the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, with a notable paucity of research from South Africa (SA). Much OAE research has been quantitative, typically employing pre- and post-test questionnaires evaluating the intervention, with few studies collecting data beyond the immediate follow-up period. Given the reported need for qualitative research, this study sought to explore the meanings and perceived benefits of Journey, a school-based OAE programme, for the learners. This study provides a unique and valuable contribution to OAE research, both for SA and internationally.

Literature Review

An underlying assumption of OAE is the premise that challenging participants will result in physical and psychological development (Czikszentmihalyi, 1990). Research suggests that demanding or stressful situations in OAE are useful for participants to develop adaptive approaches, which could assist them in future adverse situations (Overholt & Ewert, 2015).

The results of Hayhurst et al.'s (2015) two-part study of resilience in youth during a sailing voyage around New Zealand, (using a mixed-model ANOVA), reveal an increase in resilience of statistical significance (p < 0.02) for those who participated, compared to controls. The researchers acknowledged that the increases in reported levels of resilience could be due to "post-group euphoria", since they did not include a longitudinal aspect. Part two of Hayhurst et al.'s (2015) study, a repeated measures assessment of resilience was done at four points in time: a month before (T1); day 1 of the voyage (T2); the final day (T3) and 5 months after voyage (T4). They conducted other psychosocial measures of social effectiveness, self-esteem and self-efficacy at the beginning and end of the voyage. Repeated-measures ANOVA over the four time periods revealed a main effect (p < 0.001). Further analysis demonstrated a significant effect for T2-T3, indicating that resilience improved during the voyage, and this was maintained 5 months on. There were also significant increases in self-esteem, self-efficacy and social effectiveness scores. While Hayhurst et al. ' s (2015) study supports previous research, a qualitative component would have enhanced understanding of participants' perspectives on what contributed to their increased resilience.

A naturalistic mixed methods study was conducted by Thomas (2019), with year 9 private school learners (n = 260) from Brisbane, Australia and Hong Kong (HK). The Life Effectiveness Questionnaire-Version H (LEQ-H) was administered to all learners, pre-intervention and towards the end. The overall effect sizes for the Life Effectiveness Questionnaire (LEQ) were Cohen's d = 0.39 (HK) and Cohen's d = 0.51 (Brisbane), indicating positive changes in self-perceptions of learners' life effectiveness skills. Qualitative data derived from semi-structured interviews with teaching staff (n = 6), Outdoor Education (OE) leaders (n = 8) and focus groups (n = 53 learners) were presented using four themes: reflection, experiential engagement, expeditionary learning and functioning as a community. Unfortunately, data were not collected beyond the end of the programme, limiting the research since post-event euphoria was not accounted for.

Louw, Du Plessis, Meyer, Strydom, Kotze and Ellis (2012) explored the effect that an OAE programme had on 40 Black high school learners (X = 14.5 years). The experiential group (n = 20) took part in a 5-day OAE programme in the NorthWest province, SA. The LEQ-H was administered pre-OAE, immediately post-OAE and again 6 months on. Statistical analysis demonstrated effect sizes for overall life effectiveness both short-term (T1 to T2, Cohen's d = 0.35) and long-term (T1 to T3, Cohen's d = 0.50). Although this study added to previous research assessing the effect of OAE in SA, it was limited to Black high school learners and only quantitative.

In another SA study, Opper et al., (2014) evaluated the value of OAE in improving emotional intelligence in adolescent males. Employing a pre-post-test experimental design, 76 Grade 10 male learners completed the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (Bar-On & Parker, 2000) before a 23-day OAE programme, after the OAE and 3 months on. Total Emotional Quotient (EQ) scores from pre- to post-OAE showed a medium effect size, which was sustained 3 months on. A qualitative component would have enhanced the study, providing insight into what the OAE programme meant for the learners and its perceived benefits, an important omission since the success of OAE depends on learners' internalised meaning from the experience and ways it is applied beyond the experience.

Using an alternative methodology, Zygmont and Naidoo (2018) evaluated the perceived outcomes of OAE through a phenomenological study of the experiences of adolescents on an OAE programme in the Western Cape, SA. Their analysis revealed four distinct themes: once-in-a-lifetime experience, rite of passage, all-round learning and development opportunity and a long, arduous school hike. These categories related directly to programme outcomes, evolving from different levels of awareness regarding the programme experience. We conclude that for OAE to be effective, leaders should be aware of participants' perceptions of the programme and facilitate the design and implementation of the programme accordingly. There were a number of limitations to this study: a biased racial socioeconomic sample of exclusively White learners; variations in group dynamics, group leaders and routes followed: thus, each group had a different experience of the programme.

Theoretical Framework

In keeping with previous reports of OAE research, this study was based upon a social constructivist paradigm, incorporating a synthesis of Vygotsky's (1978) sociocultural theory, Dewey's (1938/1997) pragmatic and experiential learning philosophy, Bronfenbrenner's (1979) bioecological approach and elements of positive psychology. Social constructivism highlights the importance of culture and context in the co-construction of knowledge through social interactions (Raskin, 2002). This theoretical framework provided the foundations for the research aims and objectives of this study (see Figure 1).

With this study we aimed to add to and extend previous research by employing mixed methods to investigate the psychosocial outcomes of OAE on adolescents in a SA setting. There have been no studies of the outcomes of Journey at these schools, thus this study is unique in investigating the potential personal and social outcomes, the meaning and perceived benefits for the learners in this particular context. The study was guided by the following research question: What does Journey mean and what are the perceived benefits for Grade 10 learners?

Methodology

Research Setting

Journey, a 21-day experiential, cross-curricular learning OAE programme, aims to promote personal physical, intellectual, social and spiritual development. This includes self-awareness, social development, leadership development and community engagement. Learners are split into five groups of approximately 40, with four leaders per group (learners and leaders were both male and female). Covering 600 km, from the source of the Fish River to its mouth, groups journeyed simultaneously, rotating activities between hiking, cycling, kayaking, and running. Days were assigned for community work, for living solo and one "rest and create" day (see Table 1).

Research Design

In this article we report the qualitative aspects, with data drawn chiefly from semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Post-Journey surveys and learners' letters to the principals were also accessed. The methods were selected to elicit rich descriptions of the learners' experiences, expectations, concerns, and perceptions before, during and after Journey, and its effects.

Ethical approval was granted through the institutional research committee. After administrative consent from the schools, fully informed parental consent and learner assent were obtained. Survey responses and interviewee details were anonymised. We endeavoured to work confidentially, respectfully, responsibly and within careful limits to maintain integrity throughout the process. The data will be stored securely for 5 years and only used for the purposes of this study.

Participants

Grade 10 learners (46.2% female, X = 16.5) from two independent single-sex schools in the Eastern Cape, were recruited. A sample of 144 participants met the inclusion criteria and assented to take part in the study. Although participants were from diverse ethnic groups, these details are not provided as this was not the point of the research. The focus groups (N = 20), generating the majority of the qualitative data, were selected from this sample of participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection took place between September 2017 and April 2018 in four phases: Phase 1 (pre-Journey), Phase 2 (during), Phase 3 (on the final day) and Phase 4 (4 months post-Journey). Appendix A details the data collection. Through semi-structured interviews we explored learners' experiences to understand the inter- and intrapersonal dynamics and different experiences (see Table 2).

Template analysis (King, 2004), a type of thematic analysis, was selected as most suitable. We produced a list of codes (i.e. the template) to identify themes in the data. While certain of the themes were defined a priori, these could be added to or amended during data interpretation. Coding was done by applying King's (2012) procedural steps: defining a priori themes; familiarisation with the data by initial coding; initial template development and application; interpretation of findings; quality and reflexivity checks; and producing the report.

Results and Discussion

In order to gain an overview of the learners' experiences and what they valued most about Journey, a word cloud was generated from the post-Journey survey and the letters that Grade 10 learners wrote to their principals. The most frequently used words are depicted in a larger font (see Figure 2).

Referring to the word cloud and initial coding of the semi-structured interview transcripts, the acronym "flourishing" was constructed to illustrate what Journey meant. Flourishing was felt to be an apt acronym with the current increase in focus on positive psychology in education (Conoley & Conoley, 2009). In this context, flourishing is defined as a psychosocial construct that includes having rewarding and positive relationships, feeling competent and confident and believing that life is meaningful and purposeful. Although listed as independent features, the factors within the flourishing model are interdependent, where changes in one factor may cause changes in another. Each letter of the acronym is discussed below by means of references to the evidence in the data and links in the literature.

F: Friendships

L: Life lessons

O: Out-of-comfort zone

U: Ubuntu

R: Reflection

I: Intrapersonal development

S: Social development

H: Humility and gratitude

I: Individual differences (including gender)

N: Nature

G: Group dynamics

F: Friendships

Many comments in the data show that the friendship bonds and relationships that developed during Journey were deeply valued, particularly with people whom they would perhaps not usually interact with at school.

And it seems that like you end up building friendships with people that you never thought you would actually talk to. Or people that you thought would never talk to you ... (Male, solo-day interview).

Although for the most part, the comments on friendships and making new friends were positive, a few comments referred to cliques, already established prior to going on Journey, for instance: "Friend groups did not really mix, was still 'us and them' most of the time" (Female, post-Journey survey). Relationships with peers and staff are inextricably intertwined with learner well-being and mental health (Seligman, 2011), with peer relationships of particular importance (Scholte & Van Aken, 2006), and to navigate the uncertainties of adolescence.

L. Life Lessons

Many learners referred to Journey teaching them life lessons that they would perhaps not have learnt in the classroom. Post-Journey surveys and letters to the principals included comments like:

Journey was a life-changing experience.

Changes your outlook on life...

There was a sense of self-discovery in being challenged:

... I think we underestimate ourselves a lot. Coz you 're not challenged in this way in your school environment, so like I never realised like how strong my character can be at times, and ja, I think I did underestimate like my mindset and my mind, and like what I can do and what I can't. So it's a growing experience. I am learning more about myself. (Female, solo-day interview)

Research shows that OAE potentially develops life skills that are not easy to incorporate into the school curriculum, such as perseverance, leadership and communication skills (Cooley, Burns & Cumming, 2015). However, some learners felt that while they had learned life lessons, it was not as life-altering as they had anticipated.

O: Out-of-comfort Zone

The development-by-challenge theory is popular in OAE (Neill, 2008): that is when individuals face a stressful situation, they will respond by conquering their fears and grow, developing adaptive systems that may help them in future difficult situations (Overholt & Ewert, 2015). A sense of empowerment through challenge was clear for a number of learners, as in this example:

Journey is hard, Journey pushes your limits, Journey throws you out of your comfort zones and Journey tests your faith. HOWEVER with all the hardships and discomfort comes a feeling of triumph and a sense of growth that absolutely no words can describe.... (Female, letter to principal)

While numerous OAE programmes promote a development-by-challenge angle, this does not always mean that learning occurs (Leberman & Martin, 2002). For some, Journey was perceived to be too challenging, for example: "It went past a healthy challenge and became something that brought out the worst in some people and was too difficult for others ..." (Female, final focus group). Studies have shown that for personal growth, challenges need to be overcome in a supportive environment (White, 2012). Thus, a supportive environment in OAE is fundamental, with research emphasising the importance of prosocial supportive behaviour within groups (Jostad, Sibthorp, Pohja & Gookin, 2015).

U: Ubuntu

Furman and Sibthorp (2014) refer to prosocial expedition behaviour. In SA, the term "Ubuntu" refers to this concept of sharing and togetherness (Mkabela, 2015). Originating from the Zulu proverb "umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu" (translated as "one is a person through others"), it emphasises a collective spirit. In letters to the principals, the learners alluded to a sense of Ubuntu, as follows: "It was about finding strength in the unity of it all, building trust and learning to love each other, through the struggle" (Male, post-Journey survey). Unfortunately, not all groups had this sense of Ubuntu, to be explored further under group dynamics. The sense of community, feeling connected and social support is particularly important to adolescent development and understanding of self (Jostad et al., 2015).

R: Reflection

OAE as experiential learning, is based on personal growth through reflection on experiences (Opper et al., 2014). Previous research highlights solo days as an important component, leading to increased self-awareness (McKenzie, 2003) through reflective opportunities (Gassner & Russell, 2008). On Journey, learners were asked to write journals and during a solo day, through structured reflection, they were expected to write to their school principals, their parents and their future selves. As an example, this learner noted: "I have used my solo day to reflect on my journey experiences and have learnt what my weaknesses are and I am going to work on them and keep acting towards my strengths" (Female, letter to principal). Comments ranged from a focus on weaknesses and strengths, goals, achievements and future aspirations, to endorsing the benefits of reflection (Thomas, 2019).

I: Intrapersonal Development

Meta-analyses of the outcomes of OAE programmes demonstrate small to moderate effects on intrapersonal development (Neill, 2002). For some learners, Journey seemed to be beneficial to self-discovery and making more accurate self-judgements: "I've also been given the opportunity during this time to learn more about myself and think about many things such as, like, my values and morals and what I do and don't stand for" (Female, post-Journey survey). Self-confidence seemed to develop in response to overcoming challenges, taking pride in their accomplishments and feeling more confident in social contexts, which some participants reported to have been generalised into other aspects of their lives. Numerous learner comments were to "dig deep" and demonstrate determination, as shown in: "This experience is a personal growth in one' s life. You learn grit, patience, determination and life skills . it has taught me that when I'm determined, I can really achieve the things I thought I could never" (Female, post-Journey survey). A number of studies have suggested that OAE can enhance levels of resilience (e.g. Bloemhoff, 2006, 2012; Overholt & Ewert, 2015). OAE programmes provide opportunities to develop perseverance, courage from facing fears and determination, which are all aspects of improving resilience.

Learners mentioned feeling less stressed away from school, with many describing how being on Journey had helped them develop patience, empathy and tolerance. Additionally, some learners mentioned becoming more open-minded, particularly challenging their preconceived ideas about others. For example:

I think I learned that not everyone is what they seem from the outside, like from school like you see a person and you like are quick to judge what kind of person they are. Then because you 're forced to get to know them over Journey, you get to find out how they 're not always the same person you think they are. (Male, interview final day)

The above intrapersonal attributes contribute positively to social interactions.

S: Social Competence

The magnitude of relationships and social connectedness was evident from the word cloud emphasising new friends and friendships. OAE programmes are conducive to the development of social competence, because they are usually located in an unfamiliar environment, in smaller groups living in close proximity. Learners slept, travelled and connected with a smaller group of their peers. Shared experiences and shared challenges brought learners closer to form part of a common identity. In one particularly poignant comment, a learner mentioned how she got to know people on a deeper level: "... I have found that in this environment, people are more willing to listen with the intent of understanding which isn't so common at school" (Female, letter to principal). Being on Journey gave learners the time and opportunity to get to know their group members without technology or social media. Learners were exposed to diverse perspectives and were able to try out new social roles within a (hopefully) supportive setting (Richmond et al., 2018).

However, the development of social connections can be difficult for some and difficult group dynamics could detrimentally affect their experiences. Some learners referred to cliques that formed within the groups, with suggestions for the future to split friendship groups and that learners, in smaller group exercises, are compelled to interact with people outside of their friendship groups.

H: Humility and Gratitude

Both humility and gratitude are attitudes that a number of learners mentioned:

Journey was an amazing experience that allows us as humans to realize how insignificant we are in relation to the world we live in ... being put on Journey and given the minimum to survive has really made me realize how lucky I am to have what I have. (Male, post-Journey survey)

However for some, Journey was something that they neither valued nor noted benefits. This then emphasizes individual differences, since the different ways of constructing meaning were to individual attitudes, how they approached and interacted with the experience.

I: Individual Differences

Personal preferences, physical strength, fitness, motivation and previous experience with outdoor adventure activities and cultural factors are all individual differences that need to be considered. Consistent with the underlying social constructivist framework, these unsurprisingly affected the learners' experiences of Journey and the variations in perceived benefits, meanings made and outcomes, as underscored here:

I just think it's different with different people. ... life-changing could mean that you, it's helped you build character, so that's life-changing to you. Or that you've pushed physical boundaries, so that's life changing to you. Or if you met your best friend and it's made you step out of your comfort zone.... (Male, final focus group)

Studies have explored whether gender affects the outdoor education experience, with conflicting results (Gray, 2016; Whittington & Aspelmeier, 2018). In many societies there is a stereotype that presumes that males are physically stronger than females and a few learners mentioned this. Some learners referred to both gender similarities and differences, suggesting that while males coped with the physical demands, females fared better with Journey emotionally. Others appreciated that the physical aspect may be more difficult for some females, but acknowledged that this depended on the individual. Although some stereotypical differences were reported, Journey also allowed learners to challenge these.

N: Nature and Environmental Awareness

Recent research has reported the beneficial effects of being in nature (e.g. Gladwell, Brown, Wood, Sandercock & Barton, 2013) and links have been demonstrated between experiencing nature and stress reduction (Freeman & Akhurst, 2018). Learners on Journey reflected similar ideas, but interestingly this was evident in only a few comments: "Being in nature has also relieved a lot of stress and taken away some of my responsibilities" (Male, letter to principal); and "... like you 're understanding the environment and you 're one with the environment" (Male, letter to principal). Such biophilial tendencies may evoke feelings of humility in and appreciation for nature (Profice, Santos & Dos Anjos, 2016). Researchers often mention a disconnect between humans and nature, arguing that OAE is well placed to help create an awareness and appreciation of environmental issues. What was surprising in this study was how few learners freely expressed such ideas. Although mention was made of environmental challenges, mainly the drought and water shortage, this only came after explicit questions. This may well be due to their developmental stage, but could also be attributed to the mostly privileged contexts of many of the learners; where they do spend more time outdoors (perhaps taking that for granted) than in many other countries where OAE occurs.

G: Group Dynamics (including Group Leaders) As different individuals come together and form a group, the interactions prompt behaviour at group-level that influence group formation and functions in OAE (Jostad et al., 2015). Mostly, participating in OAE correlates with increases in group cohesion (Sibthorp & Jostad, 2014) and this was reportedly the case for some participants. The remoteness of the environment results in interdependence between group members, creating a supportive encouraging social system, as evidenced here:

I was lucky enough to be in Group xxx. Never in my life had I seen such a perfect mix of people, and I'm not saying we never fought or disagreed, we did, on multiple occasions but it always seemed to be functional conflict. We were a community ... a family ... we put so much trust into each other and care fiercely for one another. (Female final focus group)

For some groups, relationships improved as the learners got to know one another, but this was not so for other groups, where there was less cohesion. Prevailing hierarchies from school social networks continued in certain Journey groups, affecting the group dynamics: "... allows people to bond but they usually have popularity-based groups within the bigger groups" (Male, post-Journey survey).

Notwithstanding the impact and importance of group leadership, relatively little attention is given to this aspect in OAE research. Group leaders have a great influence on group dynamics, bringing their own personalities, abilities and expectations to the social structure of the group (Sibthorp & Jostad, 2014). For example, group leaders' unattainable expectations or shifting goals may negatively influence learner experiences (McKenzie, 2003). When participants are able to respect, appreciate and feel the support of their leaders, it makes it easier to identify with the leader and group members. For many, group leaders significantly influenced how they experienced Journey. Some seemed to appreciate the change in the adult-learner relationship, where the existing hierarchy shifted from leaders in positions of authority to being friendlier, approachable mentors. Learners also mentioned how much they valued leaders who intentionally engaged the learners and gave them some autonomy, as this remark demonstrates: "I think they (Journey Leaders) play an important role. I absolutely love [teacher] because he stepped back and gave us responsibility ..." (Male, interview final day). This is consistent with Dewey's (1938/1997) suggestion that education should develop the capacity of learners and groups to actively participate in democratic societies. However, some groups did not have the same rapport with their leaders, with some leaders apparently continuing existing patterns of hierarchy on Journey. This would have impacted the connections between group leaders and learners, influencing group dynamics and experiences.

Practical Implications of the Findings

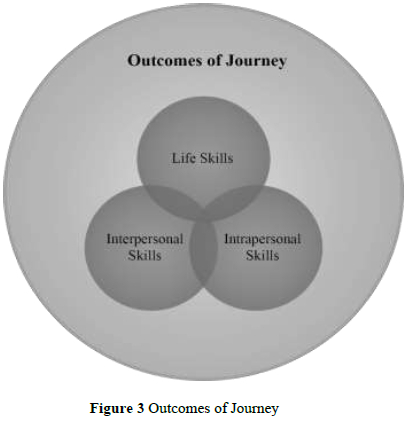

Several important practical implications arose from these findings. Journey, on the whole, appeared to be a positive experience for many of the Grade 10 learners in terms of enhancing life skills, intrapersonal skills and interpersonal skills (see Figure 3). However, not all learners experienced such positive changes. Given the complexity of adolescent development and the psychosocial outcomes that are thought to occur on OAE, this finding is perhaps not surprising.

Given that the overall findings from this study suggest personal and social development as an important outcome of Journey, this needs to be more specifically defined for each learner. Consistent with a social constructivist framework, this illustrates the importance of considering individual differences, as they inexorably influence the learners' experiences of Journey and variations in outcomes, meaning and perceived benefits. For learners to experience Journey as their own personal journey, it is important to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach. There may be ways that Journey could be crafted, planned and facilitated in order to ensure that learners feel intrinsically motivated to participate.

A suggestion is to adopt a strength-based approach to Journey. This would provide the learners with a sense of self-determination (i.e., autonomy and agency), which in turn increases their engagement and thus enhances potential outcomes. This is congruent with the underlying principles of positive psychology, whereby the use of signature strengths has been shown to be associated with improved psychological well-being (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Rather than operate from the concept of development-by-challenge common to most OAE programmes, a strength-based approach encourages growth through positive factors (Berman & Davis-Berman, 2005). It is recommended that the following are developed during Journey: positive relationships, learner engagement, positive emotions, meaning-making, competence and autonomy (see Figure 1). Adopting the metaphor that OAE is the campfire that heats up the pot to encourage personal growth, the positive factors are analogous to the logs - fuel that is added to the fire, enabling the learners to flourish. In essence, by identifying and developing their character strengths and defining their intended outcomes, learners may feel more intrinsically motivated to participate. These will then enhance positive outcomes, ensure that the experience is more meaningful to the learners and increase the chances that these benefits are transferred to other areas of their lives.

The theoretical bases and research evaluating OAE mainly originate from Western contexts, therefore this study offers a unique sociocultural perspective corroborating previous findings. However, there are a number of limitations which may influence its generalisability, including, the socioeconomic status of the learners, the length of time and associated costs of Journey, the compulsory nature of the programme and potential researcher bias.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings suggest that Journey is a challenging yet rewarding undertaking, largely beneficial for the learners, both intrapersonally and interpersonally. However, this was not the case for all learners, some of whom felt that they had not benefited. Perhaps through adopting a more explicitly strength-based approach (Passarelli, Hall & Anderson, 2010) to pre-programme briefings and in reflections during Journey, learners might feel a greater sense of autonomy, agency and competence, which could enhance intrinsic motivation to participate. This might increase the positive outcomes of Journey, while also making the experience more meaningful and valuable for learners.

Although more empirical and conceptual understanding of the ways in which OAE might benefit learners is required, the findings of this study may have implications for pedagogical policies and practice in SA and further afield. It is hoped that this research will provide a basis for considering the effects of OAE and encouraging a more widespread implementation of strength-based approaches.

Acknowledgements

Many people gave their time and support to this research project. We would like to express gratitude towards the following:

• The Grade 10 learners who participated in this study and who generously shared their experiences and stories, particularly those who formed part of the focus groups.

• Journey leaders and members of staff at Solo Camp for hosting me and allowing us access to interview members of the focus group.

• The principals of the schools for allowing me to conduct my research and for providing me access to the letters written to them on Solo Day.

Authors' Contributions

This article was written by Judith Blaine and it was supervised by Jacqui Akhurst, who also supervised Judith Blaine's PhD thesis. All images, tables and diagrams belong to the author.

Notes

i. This article is based on a doctoral thesis of Judith Blaine.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Bar-On R & Parker JDA 2000. Bar-On emotional quotient inventory: Youth version (EQ-i:YV): Technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems. [ Links ]

Berman DS & Davis-Berman J 2005. Positive psychology and outdoor education. Journal of Experiential Education, 28( 1):17-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590502800104 [ Links ]

Bloemhoff H 2006. The effect of an adventure-based recreation programme (ropes course) on the development of resiliency in at-risk adolescent boys confined to a rehabilitation centre. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education, Recreation, 28(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

Bloemhoff HJ 2012. High-risk adolescent girls, resiliency and a ropes course. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 18(Suppl. 3):128-139. [ Links ]

Bowen DJ, Neill JT & Crisp SJR 2016. Wilderness adventure therapy effects on the mental health of youth participants. Evaluation and Program Planning, 58:49-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.05.005 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Conoley CW & Conoley JC 2009. Positive psychology and family therapy: Creative techniques and practical tools for guiding change and enhancing growth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Cooley SJ, Burns VE & Cumming J 2015. The role of outdoor adventure education in facilitating groupwork in higher education. Higher Education, 69(4):567-582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9791-4 [ Links ]

Czikszentmihalyi M 1990. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Journal of Leisure Research, 24(1):93-94. [ Links ]

Dewey J 1938/1997. Experience and education. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Ee J & Ong CW 2014. Which social emotional competencies are enhanced at a social emotional learning camp? Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 14(1):24-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2012.761945 [ Links ]

Freeman E & Akhurst J 2018. Walking through and being with nature: Meaning-making and the impact of being in UK wild places. In L McGrath & P Reavey (eds). Mental distress and space: Community and clinical applications. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315620312 [ Links ]

Furman N & Sibthorp J 2014. The development of prosocial behavior in adolescents: A mixed methods study from NOLS. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(2): 160-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913489105 [ Links ]

Gassner ME & Russell KC 2008. Relative impact of course components at Outward Bound Singapore: A retrospective study of long-term outcomes. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 8(2): 133-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670802597345 [ Links ]

Gladwell VF, Brown DK, Wood C, Sandercock GR & Barton JL 2013. The great outdoors: How a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extreme Physiology & Medicine, 2:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-7648-2-3 [ Links ]

Gray T 2016. The "F" word: Feminism in outdoor education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 19(2):25-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400992 [ Links ]

Hayhurst J, Hunter JA, Kafka S & Boyes M 2015. Enhancing resilience in youth through a 10-day developmental voyage. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(1):40-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2013.843143 [ Links ]

Jones JJ & Hinton JL 2007. Study of self-efficacy in a freshman wilderness experience program: Measuring general versus specific gains. Journal of Experiential Education, 29(3):382-385. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590702900311 [ Links ]

Jostad J, Sibthorp J, Pohja M & Gookin J 2015. The adolescent social group in outdoor adventure education: Social connections that matter. Research in Outdoor Education, 13:16-37. https://doi.org/10.1353/roe.2015.0002 [ Links ]

King N 2004. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C Cassell & G Symon (eds). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

King N 2012. Doing template analysis. In G Symon & C Cassell (eds). Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Leberman SI & Martin AJ 2002. Does pushing comfort zones produce peak learning experiences? Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 7(1):10- 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400765 [ Links ]

Louw PJ, Du Plessis Meyer C, Strydom GL, Kotze HN & Ellis S 2012. The impact of an adventure based experiential learning programme on the life effectiveness of black high school learners. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 18(1):55-64. [ Links ]

Matlala MY 2011. The role of social factors influencing the moral development of black adolescents. PhD dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10500/5899. Accessed 30 April 2017. [ Links ]

McCleod B & Allen-Craig S 2007. What outcomes are we trying to achieve in our outdoor programs? Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 11(2):41-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400856 [ Links ]

McKenzie MD 2003. Beyond the "Outward Bound process": Rethinking student learning. Journal of Experiential Education, 26(1):8-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590302600104 [ Links ]

Mirkin BJ & Middleton MJ 2014. The social climate and peer interaction on outdoor courses. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(3):232-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913498370 [ Links ]

Mkabela QN 2015. Ubuntu as a foundation for researching African indigenous psychology. Indilinga - African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 14(2):284-291. [ Links ]

Neill J 2002. Meta-analytic research on the outcomes of outdoor education. Paper presented to the 6th Biennial Coalition for Education in the Outdoors Research Symposium, Bradford Woods, PA, 11 -13 January. Available at http://wilderdom.com/research/researchoutcomesmeta-analytic.htm. Accessed 20th January 2017. [ Links ]

Neill J 2008. Enhancing life effectiveness: The impacts of outdoor education programs (Vol. 1). PhD thesis. Penrith, Australia: University of Western Sydney. Available at https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:6441/datastream/PDF/view. Accessed 22 January 2017. [ Links ]

Opper B, Maree JG, Fletcher L & Sommerville J 2014. Efficacy of outdoor adventure education in developing emotional intelligence during adolescence. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 24(2):193-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2014.903076 [ Links ]

Overholt JR & Ewert A 2015. Gender matters: Exploring the process of developing resilience through outdoor adventure. Journal of Experiential Education, 38(1):41 -55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913513720 [ Links ]

Passarelli A, Hall E & Anderson M 2010. A strengths-based approach to outdoor and adventure education: Possibilities for personal growth. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(2):120-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382591003300203 [ Links ]

Payton JW, Weissberg RP, Durlak JA, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB & Pachan M 2008. The positive impact of social and emotional learning for kindergarten to eighth-grade students: Findings from three scientific reviews. Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505370.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Peterson C & Seligman MEP 2004. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Profice C, Santos GM & Dos Anjos NA 2016. Children and nature in Tukum village: Indigenous education and biophilia. Journal of Child & Adolescent Behavior, 4:6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2375-4494.1000320 [ Links ]

Raskin JD 2002. Constructivism in psychology: Personal construct psychology, radical constructivism, and social constructionism. In JD Raskin & SK Bridges (eds). Studies in meaning: Exploring constructivist psychology. New York, NY: Pace University Press. [ Links ]

Richmond D, Sibthorp J, Gookin J, Annarella S & Ferri S 2018. Complementing classroom learning through outdoor adventure education: Out-of-school-time experiences that make a difference. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(1):36-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1324313 [ Links ]

Rodkin PC & Ryan AM 2012. Child and adolescent peer relations in educational context. In KR Harris, S Graham, T Urdan, S Graham, JM Royer & M Zeidner (eds). APA educational psychology handbook (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13274-015 [ Links ]

Scholte RHJ & Van Aken MAG 2006. Peer relations in adolescence. In S Jackson & L Goossens (eds). Handbook of adolescent development. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Seligman MEP 2011. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press. [ Links ]

Seligman MEP & Csikszentmihalyi M 2000. Positive psychology: An introduction [Special issue]. American Psychologist, 55(1):5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.5 [ Links ]

Sibthorp J & Jostad J 2014. The social system in outdoor adventure education programs. Journal of Experiential Education, 37( 1 ):60-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913518897 [ Links ]

Thomas GJ 2019. Effective teaching and learning strategies in outdoor education: Findings from two residential programmes based in Australia. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(3):242-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1519450 [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

White R 2012. A sociocultural investigation of the efficacy of outdoor education to improve learner engagement. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17(1):13-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.652422 [ Links ]

Whittington A & Aspelmeier JE 2018. Resilience, peer relationships, and confidence: Do girls' programs promote positive change? Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 10(2): 124-138. https://doi.org/10.18666/JOREL-2018-V10-I2-7876 [ Links ]

Zins J & Elias M 2006. Social and emotional learning. In GG Bear & KM Minke (eds). Children's needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention. Bethesda, MD: NASP Publications. [ Links ]

Zygmont CS & Naidoo AV 2018. A phenomenographic study of factors leading to variation in the experience of a school-based wilderness experiential programme. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(1):129-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246317690686 [ Links ]

Received: 3 June 2020

Revised: 4 May 2021

Accepted: 20 August 2021

Published: 31 August 2022

Appendix A: Detailed Data Collection Procedure

Phase 1 - Pre Journey

Focus group semi-structured interviews

Two focus groups were formed (10 males and 10 females). Separate semi-structured interviews with each focus group were conducted within the school premises, lasting between 35-45 minutes. Discussion took place around the following questions:

• What do you expect to gain from Journey on both a personal level and within your group?

• What is your biggest concern about going on Journey?

• What aspect of Journey are you most looking forward to?

Phase 2: During Journey 1:1 interviews on solo day

All members of the focus groups were individually interviewed on their respective solo days since all groups passed through this point at different times, and therefore all participants were accessible. This period of time was also selected as it was a period of reflection for all learners to contemplate their experience of Journey thus far. Interviews lasted on average 10-15 minutes and discussion took place around the following questions:

• What are you enjoying the most about Journey?

• What have been your best days so far?

• What has been your least favourite thing about Journey so far?

• Have you any concerns going forward?

• How are things within your group working?

• In what ways, if any, do you think Journey has benefitted you so far?

Letters to the principal - all learners

During the solo period of Journey each learner is asked to write a letter to the school principal. The purpose of the letter is to reflect on their personal journeys at school and in particular what this physical Journey has meant to them. Although the learners' names appeared on the original letters to the principals, the copies of the letters that were used as part of the qualitative data were de-identified by the researcher (i.e. names were removed before viewing the contents of the letters). This meant that individuals could not be identified, maintaining confidentiality and anonymity.

Phase 3: Final Day of Journey

Post evaluation questionnaires - All learners

Post evaluation questionnaires were administered to all learners in order to determine the nature of their thoughts, opinions and feelings. Learners were asked to evaluate Journey based upon the following questions:

• Please could you write a few sentences to sum up your experience of Journey?

• What do you value the most having been on Journey?

• Did Journey meet your expectations? If so why/why not?

Subgroup semi-structured interviews

Members of the subgroup focus groups (i.e., two males and two females from each Journey group) were interviewed on the final day of Journey as they entered camp. Sub-groups were necessary as each Journey group took a slightly different route or means of transport down the Fish River Valley and as such, it was not possible to conduct an interview with the two main focus groups during the course of the Journey. It was also important to understand the different experiences of all Journey groups. Discussion took place around the following questions:

• What was the most significant moment for you during Journey?

• How do you feel you have benefitted as a person from this experience?

• Did Journey meet your expectations? If so, why/why not?

Phase 4: Four Months Post Journey Focus group semi-structured interviews

Prior to the end of Term 1 of the following year (which was approximately 4 months after the start of Journey), semi-structured interviews with the focus groups were conducted. As this phase took place approximately 4-months after the start of Journey, it added an important longitudinal aspect to the study, thus strengthening the study. This interval also provided a period of time in which the learners were able to reflect on their experience and possible personal growth and development. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes. Discussion took place around the following questions:

• Of the things that you learnt while on Journey, which one, in your opinion, is the most valuable to you now?

• Is there anything you learned on Journey that has negatively affected your everyday life? If so, what was it?

• Are there ways in which you have changed as a result of Journey?

• Are there ways in which you are better (or worse) off than you were before this experience?