Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n3a2086

ARTICLES

History education and changing epistemic beliefs about history: An intervention in initial teacher training

Diego Miguel-Revilla; María Sánchez-Agustí; Teresa Carril-Merino

Department of Experimental Science, Social Science and Mathematics Didactics, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain dmigrev@sdcs.uva.es

ABSTRACT

Epistemic beliefs can have an important effect on teaching practices determining how teachers approach a discipline in the classroom in different contexts. The research reported on here focused on initial teacher education, assessing the pre-service social studies teachers' epistemic beliefs about history, and their ideas regarding history education. We examined the way in which the beliefs of 59 Spanish participants had evolved after an intervention focused the fostering of historical thinking and understanding. A pre-test-post-test quasi-experimental design was applied, using the Beliefs about History Questionnaire (BHQ), which was supplemented by a qualitative approach. Results indicate progression, although it was more noticeable in pre-service primary education teachers who adhered to a more nuanced vision about historical knowledge and both objectivity and subjectivity. The way that participants with different conceptions about history thought about educational aspects were also examined and discussed. Findings suggest the effectiveness of educational interventions in initial teacher training to allow pre-service teachers to understand the specificity of this discipline.

Keywords: epistemic beliefs; historical thinking; history education; initial teacher training

Introduction

History teachers have an invaluable role in contemporary societies, not only as transmitters of knowledge about the past, but also as professionals that can help students develop disciplinary competencies and become aware of their historical consciousness (Seixas, 2017b). Adopting an adequate orientation of history education is especially important for those national contexts where recent history still plays a fundamental role in the development and understanding of national identities due to diverse reasons, such as in Spain (Martínez Rodríguez, 2014), Portugal and Brazil (Barca & Schmidt, 2013), South American nations such as Chile or Argentina (Carretero & Borrelli, 2008), Ireland (Kitson & McCully, 2005), or South Africa (Angier, 2017). In many of these national contexts the past is sometimes still regarded as controversial (Teeger, 2015) and "difficult histories", in the words of Gross and Terra (2019), are not always addressed to promote historical understanding. Teachers can provide their students with a set of critical tools that might help them establish connections between the past and the present - something that is dependent on those beliefs harboured by teachers about the specific nature and production of knowledge of an epistemological origin.

While researchers have examined the way in which epistemic beliefs can influence reasoning and other abilities and have conceptualised theoretical developmental models that try to describe progression (Kuhn, Cheney & Weinstock, 2000), initial efforts were based on broad characterisations. In contrast, the analysis of domain-specific epistemic beliefs can help the understanding of students' and teachers' ideas about the nature of knowledge in their own discipline (Buehl, Alexander & Murphy, 2002). This is a reason why focusing on history and social sciences can, in fact, provide a clearer picture of teachers' and students' reasoning and perceptions (Maggioni, Fox & Alexander, 2010).

Literature Review: Epistemic Beliefs about History and History Education

Research in history education has addressed the way in which students conceive history, examining how different visions regarding its nature can lead them to think about historical evidence in diverse ways. For instance, Lee and Shemilt (2003) developed a progression model in which they discussed how those students who regarded the past and history as analogous concepts tended to treat evidence as a direct access to what really happened. Conversely, those people that are able to conceive history as a construct usually have a more nuanced view of how to interpret and understand sources and evidence, taking into account the historical context, reliability and bias.

An analysis of the way in which teachers think about history can provide valuable information about conceptions that might influence their teaching practices. In this regard, Stoddard (2010) found that teachers' epistemic beliefs about the use of historical sources do not always automatically transfer to daily practice. Sakki and Pirttilâ-Backman (2019) found that those teachers with a naïve approach to the debate about objectivity tend to show a predilection for fostering patriotism in the classroom, and those that identified the development of critical thinking and historical consciousness among their aims adhered to a reflective epistemic stance. Complex epistemological stances are not always promoted in the curriculum, and are usually relegated in favour of a vision in which history is simply viewed as factual knowledge to be transmitted (Déry, 2017). Despite this, the most recent theoretical frameworks of historical reasoning consider the understanding about how historical knowledge is constructed and about the nature of the discipline as a key element alongside first-order knowledge and second-order concepts (Van Boxtel & Van Drie, 2018).

In the last decades, a renewed focus on historical thinking and how students should be made aware of their own historicity has clearly influenced educational research in diverse educational and national contexts. For instance, in South Africa, while new studies have focused on domain-specific epistemic beliefs (Reddy, 2020), researchers have yet to assess epistemological beliefs in history education. On the other hand, there have been very valuable efforts in South African educational research regarding the development of historical thinking (Ramoroka & Engelbrecht, 2018) and the conceptualisation of historical consciousness (Teeger, 2015), fundamental concepts related to cognition in history.

If epistemic beliefs can influence how teachers orient their daily practice, initial teacher education can have an important role to play in preparing pre-service teachers. The way that they approached their practice was analysed, which included some attempts to address epistemic issues in the classroom (VanSledright & Frankes, 2000), how a lack of first-order knowledge might impede a complex epistemological approach (Wansink, Akkerman & Wubbels, 2016), or the uneven effects of courses that explicitly address epistemic cognition in history education (VanSledright & Reddy, 2014). However, the contexts in which this was analysed have been very limited and specific, and not always in connection with initial teacher training or with key epistemological categories specifically linked with history education.

The Search for a Conceptual Framework For the last two decades, there have been considerable advances in the conceptualisation of a theoretical framework capable of outlining epistemic ideas about history. Epistemological categories were usually discussed in relation to other concepts, such as the use of evidence (Lee & Shemilt, 2003), adopted by Maggioni, VanSledright and Alexander (2009) to construct a model in which different conceptions about history could be categorised in particular stances. Maggioni and her colleagues developed a framework in which they differentiated between three different epistemic positions: a copier (or objectivist) stance, a borrower (or subjectivist) stance, and a criterialist stance (VanSledright & Maggioni, 2016). This approach was informed by general models of epistemic cognition that differentiated between levels of complexity in reasoning (King & Kitchener, 2002) with an explicit idea of progression, similar to the model developed by Martens (2015).

In Maggioni's proposal, each stance is conceptualised as a reflection of a level of higher complexity. According to this model, history has the risk of being understood as a copy of the past, and people that agree with a copier or objectivist vision tend to believe that knowledge is always available, that an undisputed and objective truth can be reached, and that opposing viewpoints about history are simply attributed to a lack of information (Chapman, 2011). The borrower (or subjectivist) stance is described as a relativistic approach to history in which the truth is not only regarded as elusive, but as sometimes conceptually impossible to reach and where interpretation assumes a key role. Finally, the criterialist stance is conceptualised as a complex approach with a clear awareness of how knowledge is produced and how interpretations vary over time. History is conceived as a construct striking a balance between naïve objectivist or subjectivist approaches.

These stances are the basis of the BHQ, an instrument developed to assess the level of agreement of history teachers with these stances (Maggioni, Alexander & VanSledright 2004; Maggioni et al., 2009). This questionnaire has been used with American pre-service teachers, but also in other educational contexts, including the Netherlands (Stoel, Van Drie & Van Boxtel, 2017), Spain (Miguel-Revilla, Carril & Sánchez-Agustí, 2017; Miguel-Revilla, Carril-Merino & Sánchez-Agustí, 2021) and Germany (Mierwald, Lehmann & Brauch, 2018). The effects of interventions or formative programmes in potential changes in epistemic cognition about history have only been tentatively examined. Alternative ways of assessing epistemic cognition in history have also been used both with students and with teachers, usually combining qualitative and quantitative methods (Nokes, 2014).

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions With this research we intended to expand on the work developed in a previous study, in which the same instrument was used in order to assess the visions of pre-service teachers (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2017). Here, the aim was to analyse pre-service social studies teachers' conceptions about history and to examine their responses while taking into account categories such as the nature of the discipline, interpretation in history, the debate about objectivity and subjectivity, and the use of evidence in historical inquiry. The main purpose was to establish a comparison between pre-service teachers' epistemic beliefs before and after a formative intervention with two distinct groups focused on how students' historical thinking and understanding are developed. We also aimed to analyse participants' ideas about how to approach history education, putting them in relation with their epistemic beliefs and establishing a comparison between groups. The research questions guiding the study were the following:

1) What are pre-service primary and secondary social studies teachers' epistemic beliefs about history?

2) What are the effects of a formative intervention that addresses how students' historical thinking and understanding are fostered?

3) How do pre-service teachers with different conceptions about history as a discipline approach history education?

Methodology

A mixed-methods design in which quantitative data were accompanied by a qualitative examination of participants' responses was used in this study. This research follows an integrated design with a concurrent sequence of implementation (Greene, 2007). To establish a comparison, the quantitative analysis followed a pre-test-post-test quasi-experimental design (Shadish, Cook & Campbell, 2002). Information was obtained from two groups, although no control group was used due to the compulsory nature of the courses and the relatively small number of students enrolled in them. Quantitative information was supplemented with a qualitative analysis that focused on four specific categories to examine participants' epistemic beliefs about history. Pre-service teachers' conceptions about how to approach history education were also inductively analysed using emergent categories (Waring, 2017).

Participants and Design of the Intervention Two different groups of pre-service teachers were selected for this study, comprising a total of 59 participants from Spain. The first group included 36 second-year pre-service teachers enrolled for a bachelor' s degree in primary education, while the second group included 23 pre-service teachers enrolled for a master' s degree in secondary education. The sampling strategy can be described as non-probabilistic, as participants were selected attending to accessibility criteria using a purposive and typical strategy (Wellington, 2015). An a priori power calculation was conducted using G*Power to examine whether the sample was adequate considering the results of previous experimental studies in the field. The analysis indicated that an estimated power of .80, similar to that found by Stoel, Van Drie et al. (2017), and an estimated effect size of d = .80, in the same range described by Mierwald et al. (2018), would require a minimum total sample size of 52 participants for two groups, a sample size comparable to that used by Stoel, Van Drie et al. (2017).

Both groups took part in an intervention that lasted a total of 15 hours in 2018. The intervention was applied separately in each case, in the framework of a course on history and social studies education that focused on characterising and providing strategies to foster the development of historical thinking and understanding. The main aim of the intervention was to help pre-service teachers understand some of the key concepts of the field in order for them to be able to use said notions to learn how to design resources or design activities in the future that could be used in primary or secondary education. For this reason, the intention with the course was to, first of all, expand the participants' theoretical notions about the potential of history education, providing examples and background information, but also, as an intended effect, to help them reflect and think about the nature of history and how to approach history education. In both instances the same professor used an identical pedagogical orientation, focusing on the same elements and utilising comparable resources.

After introducing participants to central ideas and theoretical frameworks that have conceptualised historical thinking and understanding (Lévesque & Clark, 2018), each session was dedicated to examining these notions, individually addressing the six key historical thinking concepts identified by Seixas and Morton (2013) in each of the different sessions. During the course, students were provided with theoretical tools, as well as practical examples on how to identify concepts such as historical significance, the use of evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspective and the ethical dimension of history, and how to use them in primary or secondary education classrooms (Seixas, 2017a).

Examples of different methodological strategies were also provided in the sessions, focusing on how to best address each concept in relation to the cognitive development of the students and their ideas about historical knowledge, as well as to some of the historical debates or topics being discussed in the media. For this reason, pre-service teachers also spent some sessions working with historical sources, and were taught to identify and critically examine them, and to use these resources in history education to develop historical understanding among students (Levstik & Barton, 2015). During the process, pre-service teachers were also asked to select historical sources and educational resources, to design proposals for potential teaching practices, and to take part in debates fostering a deeper reflection about the nature of history and its educational role.

Research Instrument and Data Analysis The BHQ (Maggioni et al., 2009) was applied before and after the intervention, with the informed consent of participants. The 22 items of the questionnaire, distributed in three scales (copier, borrower and criterialist), were codified using a six-point Likert scale, with values ranging from 1 to 6 (1 = Strongly disagree; 6 = Strongly agree). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the structure and psychometric properties of the instrument, which was deemed satisfactory after its application in this particular context (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2021).

Participants were also asked to respond at length on their agreement with three statements included in the BHQ: "Teachers should not question students' historical opinions, only check that they know the facts", "Even eyewitnesses do not always agree with each other, so there is no way to know what happened" and "It is fundamental that students are taught to support their reasoning with evidence." Each item was selected from one scale, using as criteria the potential information that responses might be able to provide in relation to the categories that were used.

Information obtained from the instrument was processed and analysed following two procedures. Quantitative data were transferred to the IBM SPSS software, using a technique indicated by the creators of the questionnaire in order to convert 1 to 6 Likert-scale values to -3 to +3 values (VanSledright & Reddy, 2014). Paired samples or dependent t-tests were applied to establish a comparison between the level of agreement for each of the three epistemic stances before and after the intervention.

Open-ended responses were transcribed and transferred to ATLAS.ti to codify them. After anonymising the information to reduce bias, four categories were used, including aspects related to the nature of history, issues regarding interpretation, the debate about objectivity and subjectivity, and the use of evidence in historical inquiry. These categories had been previously described by Miguel-Revilla and Fernández-Portela (2017) and applied in the study on which this work expands (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2021). Furthermore, responses provided were inductively codified using emerging categories in order to examine the participants' concerns and visions regarding history education. These were later compared with the aim of examining the way in which groups with different epistemic ideas about history approach history education, as well as the effects of the intervention.

Results

Quantitative Comparison of the Results Obtained Before and After the Interventions

The results obtained after the application of the BHQ were analysed for both groups. After testing for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and verifying all assumptions, a quantitative comparison using paired samples or dependent t-tests was applied, contrasting the level of agreement with each of the three stances before and after the intervention. Cohen's d values were provided for each analysis in order to reflect a measure of effect sizes. In the initial and final applications of the instrument, Cronbach's a coefficient ranged between .63 and .75 for the copier scale, between .61 and .58 for the borrower scale and between .70 and .80 for the criterialist scale respectively. These results were in line with previous applications of the instrument, with suboptimal a readings in some of these scales (Mierwald et al., 2018; Miguel-Revilla et al., 2021; Stoel, Van Drie et al., 2017), which are discussed later on.

Focusing exclusively on the progression evidenced by primary education pre-service teachers (cf. Table 1), the results indicate that this group favoured the criterialist position before the intervention (M = 1.43, SD = .56), and also show an important disagreement regarding the other two stances, especially with the borrower position (M = -1.38, SD = .74). Dependent t-tests indicate a statistically significant difference between the initial and final results and a large effect size only for this factor (t(35) = -5.66, p < .001, d = .87).

While participants showed a significant variation on their level of agreement with the borrower stance, the results obtained in the final test signalled their struggle to favour this position (M = -.61, SD = 1.00) after the intervention, which might indicate a more nuanced approach to this vision. The dependent t-tests did not show evidence any additional significant differences between the initial and final results for the copier (t(35) = -.79, p > .05, d = .11) or the criterialist stance (t(35) = .04, p > .05, d < .01).

For pre-service secondary education teachers (cf. Table 2) the results were very similar to the ones found in the other group, although a series of key differences could be identified. While these teachers also showed a notable level of agreement with the criterialist position, higher than the first group (M = 1.79, SD = .67), the other two stances were rejected in a more consistent way (M = -1.68, SD = .75 and M = -1.63, SD = .74 for the copier and the borrower stance, respectively).

The only statistically significant changes between the initial and the final results were the ones related to the borrower stance (t(22) = -2.81, p = .01, d = .53) with a moderate effect size. Even though the data pointed to a higher level of agreement regarding the criterialist position, and a slightly less categorical point of view in relation to the copier stance, these differences were not statistically significant (t(22) = -.50, p > .05, d = .12, and t(22) = -.42, p > .05, d = .07, respectively). Just like in the first group, while participants' epistemic beliefs did not completely change after the intervention, results indicate a more nuanced perspective, especially in relation to the borrower stance.

Qualitative Analysis of Epistemic Beliefs Before and After the Intervention

Attending to the group of pre-service primary education teachers, the results that were obtained before and after the intervention (cf. Table 3) show that the distribution of the responses in the categories differed significantly. Regarding the conception of history, 13.9% of the participants displayed a vision where the past and history were indistinguishable from each other, a key aspect of the copier stance, showing no discernible progression. On the other hand, 61.1% of the participants initially identified history with a narration, and 19.4% with a scientific discipline. Only 27.7% of teachers agreed with the first position after the intervention.

The second category focused on interpretation in history. Those participants who considered history as something analogous to the past considered history as something whose meaning had already been provided: 11.1% before the intervention, as well as 8.3% after the final test. Conversely, 52.8% of the participants initially focused on the prevalence of different interpretations, highlighting the validity of all positions and asking for "a consensus in which all points of view are taken into account" (14.PrimaryEd.Pre). While only 30.5% initially agreed that interpretation was possible in history, this percentage increased to 52.8%.

The debate regarding objectivity and subjectivity in history was analysed in the third category. Naïve positions were more categorical in nature. For instance, one participant stated that "there are different opinions, but there will always be a true one" (25.Prim.Pre). Sixty-one per cent of the participants initially displayed naïve stances, decreasing to 47.2% after working with historical thinking key concepts. The largest increase corresponded to those participants who were able to strike a balance between both objectivity and subjectivity in line with a criterialist position.

The comparison in the last category shows that participants started considering testimonies and other evidence in historical inquiry after the intervention. While 41.5% of them did not even consider these elements and instead just focused on the usefulness of "examining different points of view" (23.Prim.Pre), the figure decreased to 11.1% after the course. Responses that explicitly referred to the use of sources and evidence increased from 8.3 to 30.5%.

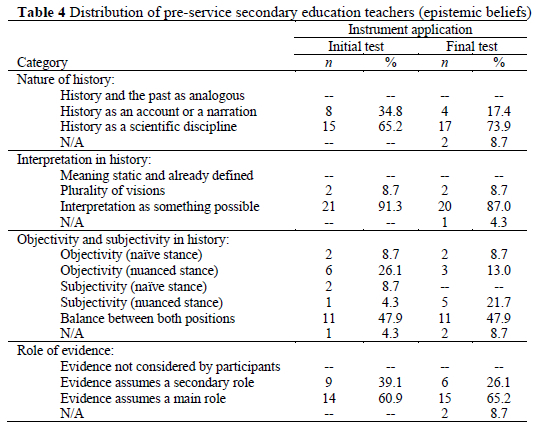

Using the same categories with secondary education pre-service teachers (cf. Table 4), progression was not as predominant as with primary teachers, although responses were in line with the criterialist stance. Participants debated between a vision of history as an account or narration (34.8%), or as a scientific discipline (65.2%), clearly opting for the second position after the intervention (73.9%). A nuanced conception was found, as participants defended that "from different accounts, a historian is capable of obtaining a guiding theme in order to know the events that happened in a particular time or place" (38.SecondaryEd.Pre), even if "there is a lack of witnesses in most of historical periods" (46.Sec.Post).

Regarding objectivity and subjectivity, this group, from the beginning, adhered to a balanced stance in which both positions were taken into account (47.9% of responses). This percentage was identical after the intervention, as participants reflected on how to reconcile the "plurality of opinions inherent to the historical discipline when working with people" (58.Sec.Pre) and yet, how "it is possible to obtain conclusions even from conflicting testimonies" (50.Sec.Post). The percentage of responses framed in naïve stances was comparably lower than in the other group. Data also suggest progression towards a nuanced subjectivist position (from 4.3% to a 21.7%) in line with quantitative findings. The same applied regarding the perception of the role of evidence in historical inquiries, as 60.9% of the participants initially highlighted the critical use of sources and documents (65.2% after the final test). In contrast to the first group, all participants mentioned the necessity to take evidence into account, even if it merely assumed a secondary role for 39.1% and 26.1% of the participants before and after the intervention, respectively.

Educational Approaches and Epistemic Beliefs about History

Both pre-service primary and secondary education teachers spontaneously made reference to a considerable number of ideas that were related to educational aspects (cf. Table 5). These categories, while linked to the discipline of history, went beyond a discussion of epistemic beliefs, and provided information about how pre-service teachers perceived that history education should be addressed in the classroom.

Among the main ideas that were identified during the analysis, the one that was more frequently repeated by pre-service primary education teachers was that teaching reasoning should be addressed in history classes. For them, "it is essential that each person learns how to defend their arguments' (15.Prim.Pre), because "no matter what their opinion is, it should be adequately substantiated' (06.Prim.Pre). This idea was reinforced by the intervention in both groups: this notion was reiterated by 58.3% of primary teachers in the final questionnaire and by 47.8% of their counterparts, highlighting that "it is fundamental for students to think and defend their opinion in a rigorous way" (43.Sec.Post).

Each group showed particular preferences. A very substantial focus on the promotion of critical thinking could be observed among pre-service secondary teachers (65.2% initially and 52.2% later on) as many of them clearly stated that "teachers should ask students about their historical opinions not only to learn about their knowledge, but also to determine their critical sense" (51.Sec.Pre). Pre-service primary teachers also shared this opinion, and although only 16.7% of them cited this aspect before the intervention, the course seemed to have encouraged 22.2% to spontaneously refer to this idea in the final questionnaire.

Both groups explicitly referred to the promotion of historical thinking - probably as a result of the intervention. Participants stated that teachers should assess "whether [students] have understood aspects related to historical time, causes and consequences, historical empathy, presentism, etc." (53.Sec.Post), or that pupils should focus on "the motivation of historical actors in order to understand the meaning of their actions" (09.Prim.Post). Secondary teachers cited this issue with higher frequency (21.7%) than their counterparts (just 8.3%).

Additionally, pre-service primary education teachers placed high value on the idea that students should be able to express their opinions about history (41.7% before; 22.2% after), as "each person has a right to give their own opinion" (11.Prim.Pre). A significant number of them (33.3%) initially highlighted that "everybody's opinions should be respected" (03.Prim.Pre).

Pre-service secondary education teachers seemed to be initially more concerned about the efficacy of learning practices (17.4%) or the link between the past and the present (8.7%), although some of these views seemed to subside after the intervention.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study we examined pre-service teachers' beliefs about history and the effects of an intervention that was designed to explicitly work with historical thinking concepts. Firstly, the quantitative comparison of the results obtained using the BHQ before and after the intervention showed progression, but not in all categories. While participants did not fundamentally change their level of agreement with the epistemic stances, they acquired a significantly more nuanced vision of the borrower (or subjectivist) position. This challenges the expectation that participants would be able to reinforce their criterialist position, but supports the results obtained by Stoel, Van Drie, et al. (2017), who report higher levels of agreement with the borrower or subjectivist stance after a comparable intervention.

Both pre-service primary and secondary education teachers showed a similar predisposition, rejecting the copier and borrower visions and showing preference for the criterialist stance. The second group displayed a more coherent position, with a higher level of agreement with a criterialist point of view, rejecting the other two stances. This preference corroborates similar studies with both pre-service teachers (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2017, 2021; VanSledright & Reddy, 2014) and students (Mierwald et al., 2018; Stoel, Logtenberg, Wansink, Huijgen, Van Boxtel & Van Drie, 2017). Despite these differences, the intervention seems to have affected both groups in a similar way with regard to the borrower stance.

Secondly, the results of the qualitative comparison signal a clear contrast between pre-service primary and secondary teachers. The first group showed a tendency to conceive history as an account or a narration, and was aware that there were many and diverse points of view about what happened in the past, even though they did not know how to discriminate among them and did not consider evidence. Participants adhered to one of the less complex categories described by Lee and Shemilt (2003), while also adopting naïve objectivist and subjectivist points of view with a general lack of awareness regarding the specificity of historical inquiry.

Significant progression in all four categories assessed was found after the intervention, in line with the aim of the formative intervention. Participants' considerations about history seemed to have changed, as a majority of them considered it a scientific discipline instead of a mere account. At the same time, the participating pre-service teachers highlighted the possibility of interpretation in history, and considered evidence as a central concept to be addressed in the classroom. Finally, their ideas about subjectivity and objectivity in history seemed to have evolved towards more nuanced considerations. This corroborates previous studies documenting how interventions have the ability to transform pre-service teachers' (VanSledright & Reddy, 2014) and students' epistemic beliefs about history (Mierwald et al., 2018; Nokes, 2014).

The effects of the course appeared to have been less noticeable for pre-service secondary education teachers. Participants in this group consistently showed more complexity in their open responses than their counterparts, both in the initial and final questionnaires, supporting the quantitative analysis. They regarded history mainly as a scientific discipline analysed through sources and contrasting evidence where nuanced and balanced visions regarding the objectivity debate can coexist. After the course, all these positions were reinforced in line with a criterialist stance.

The fact that the intervention seemed to have been more useful for primary than for secondary education pre-service teachers might be explained by their academic background (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2021). As opposed to primary teachers, secondary education teachers in Spain only begin their studies as teachers after finishing their studies in history or other social sciences. They are accustomed to disciplinary inquiry, and tend to approach historical debates considering both interpretations and facts. These results are in line with those obtained by VanSledright and Reddy (2014), who described the uneven effect of a course with pre-service teachers, but did not imply that an intervention was not useful for secondary education teachers. The quantitative and qualitative analyses indicate that this group moved towards a more nuanced subjective stance, something that might have entailed a more complex vision about how knowledge in history was constructed, instead of just an expression of a mere relativistic point of view (Stoel, Logtenberg, et al., 2017).

A qualitative examination of the participants' responses was also used to assess their visions and ideas about history education. Both groups underscored different elements, something that may hint at how diverse conceptions about history can determine the different ways that history education might be addressed in the classroom. Concerns were diverse, making interpretation difficult, but primary education teachers mentioned the need for students to express themselves and respect other people's views more often. Again, this might be a result or an expression of their academic background, more concerned with instructional aspects and how to manage pupils' global needs in primary education, than with disciplinary history.

While participants in both groups argued about the need to teach students how to reason and mostly had a negative vision of memorisation, secondary education teachers highlighted the necessity to foster critical thinking much more. These results are in line with the data obtained from studies in which teaching goals in relation to epistemic beliefs were explored and where critical thinking was detected as a fundamental objective by history teachers all across Europe (Sakki & Pirttilã-Backman, 2019). This intervention could also have reinforced the need to foster historical thinking, to link the past and the present, or to focus on the public or social dimension of history as a useful strategy in history education (Miguel-Revilla & Sánchez Agusti, 2018). A contrasting view between the two groups hint that differences in epistemic beliefs may influence the way in which pre-service teachers conceive the orientation of their teaching practice and the topics that concern them most.

At the same time, the results reinforce the importance of initial teacher education, especially for those specific cases where teachers have the difficult task of addressing a very influential recent history, something that many nations on many different continents and in different contexts, such as Spain, Canada, Chile, Ireland or South Africa have in common (Angier, 2017; Gross & Terra, 2019). Epistemic beliefs, among many other factors, can play a key role in the development of teaching practices, and learning how to adequately address a national past that is still considered controversial should be one of the aims of teacher education (Chikoko, Gilmour, Harber & Serf, 2011), especially in emerging and changing societies (Teeger, 2015) where the educational system and curriculum play a fundamental role to shape the national self-image and identity of the nation (Carretero, 2017).

Limitations and Areas for Further Study As limitations of this study, it should be noted that the scope of this research was confined to an analysis of the effects of a formative intervention. A sample size of a total of 59 participants can be described as limited, but was useful to corroborate results found in other national contexts. The instrument used in the study could be regarded as another limitation. Although the BHQ is based on a very solid theoretical framework, and a CFA was successfully applied to assess its structure and properties in this context (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2021), in this and other studies, issues with the internal consistency of the BHQ's scales were noted (Miguel-Revilla et al., 2017; Stoel, Van Drie, et al., 2017). The design of some of the items might be one of the main factors, as some items also introduce an educational perspective instead of focusing exclusively on epistemological ideas. Future efforts in designing a new instrument or adapting the current one might take this into account.

Epistemic beliefs about history do not operate in isolation, and can affect the way in which teachers approach history education. Initial teacher training has a strong responsibility of providing teachers with the adequate tools to improve their teaching practices. With this study we have shown that an intervention explicitly focused on the fostering of historical thinking can affect pre-service teachers, making them more aware of the disciplinary dimension of history while also promoting nuanced epistemic positions. While academic background can affect how history and history education are conceived, an adequate orientation can provide pre-service teachers with a complex understanding of the specificities of historical knowledge. Despite the limitations of this study, future research might expand on these aspects, further examining domain-specific epistemic differences among groups, and how formative programmes may be tailored to adapt particular needs.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Spanish Government's Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MINECO), and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), under Grant BES-2014-068910 in the framework of project EDU2013-43782-P. The work was also supported by GIR EDUHIPA -Universidad de (University of) Valladolid (U01900056).

Authors' Contributions

DMR: conceptualisation; theoretical framework; data collection; data analysis; writing of the manuscript. MSA: data analysis; writing of the manuscript. TCM: data analysis; writing of the manuscript. All authors read and agreed to the final published version of the manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Angier K 2017. In search of historical consciousness: An investigation into young South Africans' knowledge and understanding of 'their' national histories. London Review of Education, 15(2): 155- 173. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.15.2.03 [ Links ]

Barca I & Schmidt MA 2013. La consciencia histórica de los jóvenes brasileños y portugueses y su relación con la creación de identidades nacionales [Historical consciousness in Portuguese and Brazilian youngters and its relationship with the creation of national identities]. Educatio Siglo XXI, 31(1):25-46. Available at https://revistas.um.es/educatio/article/view/175091/148231. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Buehl MM, Alexander PA & Murphy PK 2002. Beliefs about schooled knowledge: Domain specific or domain general? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(3):415-449. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1103 [ Links ]

Carretero M 2017. Teaching history master narratives: Fostering imagi-nations. In M Carretero, S Berger & M Grever (eds). Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4 [ Links ]

Carretero M & Borrelli M 2008. Memorias recientes y pasados en conflicto: ¿cómo enseñar historia reciente en la escuela? [Recent memories and pasts in conflict: How to teach recent history at school]. Cultura and Educacion, 20(2):201 -215. https://doi.org/10.1174/113564008784490415 [ Links ]

Chapman A 2011. Historical interpretations. In I Davies (ed). Debates in history teaching. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Chikoko V, Gilmour JD, Harber C & Serf J 2011. Teaching controversial issues and teacher education in England and South Africa. Journal of Education for Teaching, 37(1):5-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2011.538268 [ Links ]

Déry C 2017. Description et analyse des postures épistémologiques sous-tendues par l'épreuve unique ministérielle de quatrième secondaire en Histoire et éducation à la citoyenneté [Description and analysis of the epistemological postures underpinned by the 10th grade History and Citizenship Education (HCE) uniform examination]. Revue des sciences de l'éducation de McGill [McGill Journal of Education], 52(1):149- 171. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040809ar [ Links ]

Greene JC 2007. Mixed methods in social inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Gross MH & Terra L (eds.) 2019. Teaching and learning the difficult past: Comparative perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

King PM & Kitchener KS 2002. The reflective judgment model: Twenty years of research on epistemic cognition. In BK Hofer & PR Pintrich (eds). Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Kitson A & McCully A 2005. 'You hear about it for real in school.' Avoiding, containing and risk-taking in the history classroom. Teaching History, 120:32- 37. [ Links ]

Kuhn D, Cheney R & Weinstock M 2000. The development of epistemological understanding. Cognitive Development, 15(3):309-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2014(00)00030-7 [ Links ]

Lee PJ & Shemilt D 2003. A scaffold, not a cage: Progression and progression models in history. Teaching History, 113:13-23. [ Links ]

Lévesque S & Clark P 2018. Historical thinking: Definitions and educational applications. In SA Metzger & LM Harris (eds). The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning. Malden, MA: Wiley. [ Links ]

Levstik LS & Barton KC 2015. Doing history: Investigating with children in elementary and middle schools (5th ed). New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315818108 [ Links ]

Maggioni L, Alexander P & VanSledright B 2004. At a crossroads? The development of epistemological beliefs and historical thinking. European Journal of School Psychology, 2(1-2):169-197. [ Links ]

Maggioni L, Fox E & Alexander PA 2010. The epistemic dimension of competence in the social sciences. Journal of Social Science Education, 9(4): 15-23. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/276124882.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022. [ Links ]

Maggioni L, VanSledright B & Alexander PA 2009. Walking on the borders: A measure of epistemic cognition in History. The Journal of Experimental Education, 77(3):187-214. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.77.3.187-214 [ Links ]

Martens M 2015. Students' tacit epistemology in dealing with conflicting historical narratives. In A Chapman & A Wilschut (eds). Joined-up history: New directions in history education research. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Martínez Rodríguez R 2014. Profesores entre la Historia y la memoria. Un estudio sobre la enseñanza de la transición dictadura-democracia en España [Teachers between history and memory. A study on the teaching of the dictatorship-democracy transition in Spain]. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales, 4(13):41-48 https://doi.org/10.1344/ECCSS2014.13.4 [ Links ]

Mierwald M, Lehmann T & Brauch N 2018. Zur veranderung epistemologischer überzeugungen im schülerlabor: Authentizität von lernmaterial als chance der entwicklung einer wissenschaftlich angemessenen überzeugungshaltung im fach geschichte? [Changing epistemological beliefs in student labs: Authentic learning materials as a chance to foster the development of academically adequate beliefs in the domain of history?]. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 46(3):279-297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-018-0019-7 [ Links ]

Miguel-Revilla D, Carril MT & Sánchez-Agustí M 2017. Accediendo al pasado: Creencias epistémicas acerca de la Historia en futuros profesores de Ciencias Sociales [Accessing the past: Epistemic beliefs about history in social studies pre-service teachers]. Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de Las Ciencias Sociales, 1:86-101. https://doi.org/10.17398/2531-0968.01.86 [ Links ]

Miguel-Revilla D, Carril-Merino T & Sánchez-Agustí M 2021. An examination of epistemic beliefs about history in initial teacher training: A comparative analysis between primary and secondary education prospective teachers. The Journal of Experimental Education, 89(1):54-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2020.1718059 [ Links ]

Miguel-Revilla D & Fernández Portela J 2017. Creencias epistémicas sobre la Geografía y la Historia en la formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Infantil y Primaria [Epistemic beliefs about Geography and History in Early Childhood and Primary Education initial teacher training]. Didáctica de Las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales, 33:3-20. https://doi.org/10.7203/dces.33.10875 [ Links ]

Miguel-Revilla D & Sánchez-Agustí M 2018. Conciencia histórica y memoria colectiva: Marcos de análisis para la educación histórica [Historical consciousness and collective memory: Analytical frameworks for historical education]. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 65:113-125. https://doi.org/10.7440/res65.2018.10 [ Links ]

Nokes JD 2014. Elementary students' roles and epistemic stances during document-based history lessons. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(3):375-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2014.937546 [ Links ]

Ramoroka D & Engelbrecht A 2018. The dialectics of historical empathy as a reflection of historical thinking in South African classrooms. Yesterday & Today, 20:46-71. https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2018/n19a3 [ Links ]

Reddy L 2020. An evaluation of undergraduate South African physics students' epistemological beliefs when solving physics problems. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 16(5):em1844 https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/7802 [ Links ]

Sakki I & Pirttilä-Backman AM 2019. Aims in teaching history and their epistemic correlates: A study of history teachers in ten countries. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(1):65-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1566166 [ Links ]

Seixas P 2017a. A model of historical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(6):593-605. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363 [ Links ]

Seixas P 2017b. Historical consciousness and historical thinking. In M Carretero, S Berger & M Grever (eds). Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52908-4 [ Links ]

Seixas P & Morton T 2013. The big six: Historical thinking concepts. Toronto, Canada: Nelson Education. [ Links ]

Shadish WR, Cook TD & Campbell DT 2002. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Stoddard JD 2010. The roles of epistemology and ideology in teachers' pedagogy with historical 'media.' Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 16(1):153-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600903475694 [ Links ]

Stoel G, Logtenberg A, Wansink B, Huijgen T, Van Boxtel C & Van Drie J 2017. Measuring epistemological beliefs in history education: An exploration of naïve and nuanced beliefs. International Journal of Educational Research, 83:120-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.03.003 [ Links ]

Stoel GL, Van Drie JP & Van Boxtel CAM 2017. The effects of explicit teaching of strategies, second-order concepts, and epistemological underpinnings on students' ability to reason causally in history. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(3):321-337. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000143 [ Links ]

Teeger C 2015. "Both sides of the story": History education in post-apartheid South Africa. American Sociological Review, 80(6):1175-1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415613078 [ Links ]

Van Boxtel C & Van Drie J 2018. Historical reasoning: Conceptualizations and educational applications. In SA Metzger & LM Harris (eds). The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning. Malden, MA: Wiley. [ Links ]

VanSledright B & Reddy K 2014. Changing epistemic beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teacher. Revista Tempo e Argumento, 6(11):28-68. https://doi.org/10.5965/2175180306112014028 [ Links ]

VanSledright BA & Frankes L 2000. Concept- and strategic-knowledge development in historical study: A comparative exploration in two fourth-grade classrooms. Cognition and Instruction, 18(2):239-283. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532690XCI1802 [ Links ]

VanSledright BA & Maggioni L 2016. Epistemic cognition in history. In JA Greene, WA Sandoval & I Brâten (eds). Handbook of epistemic cognition. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wansink BGJ, Akkerman S & Wubbels T 2016. The Certainty Paradox of student history teachers: Balancing between historical facts and interpretation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56:94-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.005 [ Links ]

Waring M 2017. Grounded theory. In RJ Coe, M Waring, LV Hedges & J Arthur (eds). Research methods and methodologies in education (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Wellington J 2015. Educational research: Contemporary issues and practical approaches (2nd ed). London, England: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Received: 13 August 2020

Revised: 27 June 2021

Accepted: 16 August 2021

Published: 31 August 2022