Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 n.2 Pretoria May. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n2a1989

ARTICLES

Reducing school violence: A peace education project in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Lucia Zithobile NgidiI; Sylvia Blanche KayeII

IDepartment of Human Resources Management, Faculty of Management Sciences, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa. lucian1@dut.ac.za

IIPeacebuilding Programme, International Centre of Non-Violence (ICON), Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Violence occurring in South African schools takes various forms and is a concern for all stakeholders. All forms of violence have negative effects, i.e. physical and psychological, educational damage and societal breakdown. The overall aim of the study reported on here was to explore the nature, causes and consequences of school violence, and then to design an effective intervention strategy to reduce it. In this study we used action research methodology in which stakeholders were empowered to interrupt the occurrence of violence, stop the spread of violence and change group/community norms regarding violence. This strategy of violence reduction was tested at 1 school in Umlazi, in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, in 4 stages: initial data collection, formation of an action team, design and implementation of a strategy, and evaluation of its efficacy. The action team was composed of teachers, community members, parents and learners who developed a strategy entitled, We Care (WC). Initial from both schools data showed that schools were unsafe, with school violence caused by substance abuse, theft, vandalism, physical violence, religious discrimination, sexual violence, cyber bullying, gender-based violence and gambling. WC clustered abnormal behaviour patterns demonstrated by learners into categories: violent cases and behavioural indicators of physical, sexual, alcohol and drug abuse. WC assisted high risk learners who had decided to act non-violently, help victims and assist parents and community members who perpetrated violence. A preliminary evaluation was conducted 1 year later and WC reported that they had developed capacity to assist with these categories of violence, leading to a reduction in violent behaviour at the school.

Keywords: conflict transformation; empowerment; non-violence; participatory research; school violence

Introduction

The scourge of violence in South African schools is a grave cause for concern: daily reports appear in print and electronic media regarding the high levels of physical, psychological and sexual violence (Meyer & Chetty, 2017:121). Increasingly, knives, guns, and other weapons are part of daily school life (Hendricks, 2018:76). Prevalent forms of school violence include bullying, fighting, stabbing, rape and murder (Mncube & Steinmann, 2014:204). Burton and Leoschut (2013:7) found that in 121 South African secondary schools, more than a fifth of learners had experienced violence at school, 12.2% had been threatened with violence, 6.3% had been assaulted, 4.7% had been sexually assaulted or raped and 4.5% had been robbed at school.

As early as 2001, the Department of Education (DoE) launched preventative and punitive programmes to fight the increase in school violence. Preventative measures include, Stop Rape, School-Based Crime Prevention, Management of Physical Violence at School, Opening Our Eyes and the National Strategy for the Prevention and Management of Alcohol and Drug Use Amongst Learners in Schools (Department of Basic Education [DBE], Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2013:7). Punitive interventions include office referral, security measures such as the partnership agreement between the DoE and the South African Police Services (SAPS) to prevent, manage and respond to incidents of violence in schools (DBE, RSA, 2013:7). Despite the introduction of such interventions, South Africa continues to experience high rates of school violence (Mncube & Steinmann, 2014:204). The reason for this is arguably that punitive approaches used for generations in South African schools were an ineffective strategy to manage misbehaviour (Jansen & Matla, 2011:85). This method determined what rule was broken, who was to blame, and what the punishment should be. Netshitangani (2018:163) fears that when schools focus on violence control strategies such as suspension, expulsion, arrests and fines imposed on parents or guardians, more innovative, inclusive and effective ways of dealing with violence are ignored. Further, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, has transformed the traditional aims of punishment and stresses the importance of rehabilitation of offenders through reconciliation with victims and the community at large (Wachtel, 2016:3) - a more inclusive strategy.

The study reported on here was undertaken at one secondary school in Umlazi, south of Durban. We tested the theory that all stakeholders - educators, learners, parents and community - need to be empowered and should adopt methods of dealing with conflict in socially-acceptable and non-violent ways in order to curb the cycle of violence. The specific objectives of the study were to explore the nature, causes and consequences of violence in high schools; evaluate the effectiveness of current strategies used to reduce violence in schools; investigate different strategies that can be applied by each stakeholder in violence reduction, and design, implement and evaluate alternative strategies to reduce school violence and test this model in Umlazi, South Africa. This study was underpinned by the Cure Violence model developed by Gary Slutkin (2013:11.27), which likens violence to a communicable disease that can spread from person to person. Violence, as infectious diseases, maims and kills people, and can spread from person to person among people in a locality (Ransford, Kane & Slutkin, 2013:235; Toscano, 2015:6). Violence is similar to contagious diseases in the following ways: firstly, violence clusters in certain areas, much like a disease such as cholera or tuberculosis (TB); secondly, violence spreads like a disease; and lastly, violence is transmitted through exposure. In order to change group and community culture regarding violence, one needs to view violence through a health lens and treat it as a health issue.

Literature Review

A multi-faceted phenomenon

School-based violence in South Africa is a multi-faceted phenomenon. Different parties within the school environment are involved: perpetrators of violence; victims of violent acts and witnesses to acts of violence. In some cases, perpetrators are also victims or witnesses. For example, if a child is a victim at home and treated violently by his/her caregivers, the child may well become a perpetrator at school. Figueiredo and Dias (2012:704) explain this in that children observe parental behaviour and incorporate what they see in their own lives. The ways in which violence occurs are also very varied. Learners may act violently towards each other or towards educators and educators may inflict violence on learners (Burton & Leoschut, 2013:vii). In some cases, problems originate from outside the school environment but manifest in the school (Ncontsa & Shumba, 2013:1).

Structural violence is a form of violence with a destructive effect on perpetrators, victims and witnesses. According to the Centre for Health Equity Research Chicago (2018), structural violence refers to the multiple ways in which social, economic and political systems expose particular populations to risks and vulnerabilities leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Those systems include income inequality, racism, homophobia, sexism, ableism and other means of social exclusion leading to vulnerabilities such as poverty, stress, trauma, crime, incarceration, lack of access to care, healthy food and physical activity. The dominant discourse is silent on issues around race and class with regard to school violence. The majority of violent communities and schools are in high poverty areas (Meyer & Chetty, 2017:123). These authors feel that the dominant discourse sanctions the notion that violence is expected from poor people because of their lifeworld. There is evidence in South Africa that there are huge structural and organisational differences between schools previously reserved for White learners known as former Model C schools and schools in disadvantaged communities (Meyer & Chetty, 2017:123). Johnson, Hodges and Monk (2000:191) explain that former Model C schools have historically enjoyed good facilities and resources, expectations of academic success and manageable numbers of learners in classrooms. According to Veriava (2012:para,1), the juxtaposition of "tree schools" (schools without classrooms or basic services) against the former Model C schools with their Olympic-size swimming pools, multiple sports fields and well-equipped laboratories and libraries, highlights the enduring infrastructure disparity in South Africa's public schools. Between these extremes, there exists a wide spectrum of schools, from traditional mud structures and township schools to urban and suburban schools. Veriava (2012:para. 2) further identifies a correlation between the wealth of a school and its violent behaviour: the least well-off schools, mainly Black, are vulnerable to surrounding criminal elements because of poor security such as unfenced school premises. It is further not certain that the learners' most urgent needs are addressed. This is supported by Johnson, Burke and Gielen (2011:332) who claim that a school's social and physical environment influence the degree of violence that takes place at the school. These authors posit that learner perceptions correlate poor school security to disorder, greater presence of drugs and graffiti, and an increase in school violence.

According to Draga (2016:238), the DoE's own statistics, released in 2015, highlight these painful disparities. They show that of the 23,589 previously disadvantaged schools in the country, 77% do not have stocked libraries, 86% have no laboratory facilities, and 5,225 schools have either an unreliable water supply or none at all. A total of 913 schools are expected to function without electricity, and a further 2,854 must make do with an unreliable supply. These circumstances may result in the learners being disenchanted and poorly behaved. This is contrary to former Model C schools where all schools enjoy adequate infrastructure. These differences are likely to have far-reaching consequences on the levels and characteristics of school violence.

According to Hendricks (2018:76), violence in the school context can range from psychological to physical forms of violence. The South African Council for Educators (SACE, 2011:6) lists the different types of violence as bullying, theft of property, robbery and vandalism, sexual violence, harassment and rape, gang-related violence, violence related to drug abuse, physical violence and use of weapons, shooting, stabbing and murder, violence through student protests, and racially-motivated violence.

Causes of school violence

Mkhize, Gopal and Collins (2012:40) state that actions that are harmful or inconsiderate of the well-being of others (antisocial behaviour) are learned and maintained through environmental experiences. Learners who are exposed to an antisocial environment learn to engage in antisocial behaviour. Society exposes learners to new behaviour which has not been acquired at home during their childhood. This behaviour may be positive or negative, depending on the environment. Learners may experience psychological problems in adjusting to this behaviour and eventually believe that violence is the only way to address problems (Mkhize et al., 2012:40). Van der Westhuizen and Maree (2010:4) warn that experiences of violence have become normalised within the South African society. This is supported by current crime statistics. According to Crime Stats South Africa, murders occurring in South Africa increased from 20,336 to 21,022 between 2018 and 2019, more than a 3% increase from the previous year (SAPS, n.d.). According to Pahad and Graham (2012:10), schools are microcosms of the broader communities in which they are located. For this reason, the social ills prevalent in communities are known to permeate the school environment to various degrees. This indicates that in trying to understand school-based violence, one cannot divorce the neighbourhood in which the school is located from the high rate of school violence.

Consequences and extent of school violence

School violence has an undesirable impact on the lives of young people, educators and parents, and also negatively influences effective teaching and learning (Mkhize et al., 2012:40). Mkhize et al. (2012) conducted a study in the Swayimana rural area in KwaZulu-Natal and concluded that the experiences of violence by young people are likely the results of a wide range of emotional, behavioural and educational outcomes which occur across a victims' entire lifespans. Singh and Steyn (2014:84) concur stating that learners with antisocial and violent behaviour tend to have low self-esteem and have experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

According to Njuho and Davids (2012:271), violence in schools affects every stakeholder operating within the environment, who reported that much of the violence experienced by learners in schools is perpetrated by other stakeholders. Espelage, Enderman, Brown, Jones, Lane, McMahon, Reddy and Raynold (2013:75) believe that there are incidents where learners also attack educators, but this area has unfortunately been neglected and understudied. Educators are not only the victims of learner abuse but some are the abusers themselves. Educator abuse of learners can include corporal punishment, verbal or sexual attacks.

Learners have complained about their experiences of school violence that include sexual abuse, being beaten, caned or spanked by educators or principals for misbehaviour in school (Meyer & Chetty, 2017:122). Although the South African Schools Act (Act 84 of 1996) (RSA, 1996) forbids corporal punishment, there seems to be a high reliance on physical punishment in schools (Meyer & Chetty, 2017:122). The extent of violence in South African schools varies from minor to major crimes and offenses.

Strategies on school violence reduction

Schools in South Africa have primarily relied on two strategies to stop violence: punitive and security. As noted in the introduction, the DoE had developed a range of interventions to fight the increase in school violence, which included programmes like Stop Rape and School-Based Crime Prevention (DBE, RSA, 2013:7). Several other initiatives were the formulation of school safety committees and the Hlayiseka early warning system that provides guidelines for monitoring school safety. The Hlayiseka early warning system is a management tool for principals, school governing bodies (SGBs) and educators on how to identify, prevent and manage risks and threats of crime and violence in schools; it includes codes of conduct for learners, positive discipline and classroom management (dBE, RSA & SAPS, n.d.:para. 2). Nevertheless, most of these are post-violent strategies, as they only apply once the act of violence has been committed. If they focus solely on violence control measures rather than educating learners to resolve conflicts positively and non-violently, solutions are incomplete as preventative and educative methods are needed.

Conceptual Framework

School violence is a complex issue with a variety of influencing factors, particularly the environment in which the school is located. Furthermore, the shift from punitive strategies to more inclusive and rehabilitative methods of changing behaviour (Wachtel, 2016:3) is encouraging and has led to several new strategies (discussed above) in which learners are educated to resolve conflict non-violently. One is the Cure Violence model in which violence is considered as a disease, as a possible means of educating and transforming learners and the school community from accepting violent behaviour as an acceptable choice. The idea of treating violence as a disease was developed by a Chicago physician, Gary Slutkin. Sanburn (2016:24) explains that in 2000, Slutkin started Chicago Ceasefire (now known as the Cure Violence model), a group which tapped people with connections to high crime areas to serve as "violence interrupters." After receiving tips from community members, they reached out to people who had experienced a violent episode, mediated on-going conflicts and worked with high-risk residents to change their behaviour, very similar to the way in which doctors treat outbreaks of TB and cholera (Butts, Wolff, Misshula & Delgado, 2015:1). It worked. Within a year, Slutkin's approach led to a 67% decrease in shootings in one of Chicago's most violent areas (Sanburn, 2016:24).

Since then, Cure Violence initiatives have led to similar results in other cities. According to Maguire, Oakley and Corsaro (2018:41), the Ministry of National Security in Trinidad and Tobago established the Citizen Security Program (CSP) aimed at reducing violence in 36 communities. CSP adopted the Cure Violence approach. On evaluation, the programme worked well. It prevented the escalation of tension that was likely to lead to violence, reduced the likelihood that high-risk individuals would engage in criminal and antisocial behaviour, improved public perceptions of safety, and increased coordination and collaboration among stakeholders involved in delivering violence prevention services.

According to the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2013:108), the Cure Violence model deploys a new type of worker called "violence interrupters" who are specially qualified and trained to locate potentially lethal, on-going conflicts and to respond with a variety of conflict mediation techniques to prevent imminent violence and to change the norms around the perceived need to use violence. Violence interrupters are culturally appropriate workers who live in the affected community, are known to high-risk individuals and have possibly themselves been gang members or spent time in prison, but have made a change in their lives and turned away from crime (Slutkin, Ransford, Decker & Volker, 2014:44). Butts et al. (2015:2) emphasise that violence interrupters are selected for their ability to establish relationships with the most high-risk youth in the community, usually young men between the ages of 15 and 30. Their main function is to block the transmission of violence from one person to another by defusing potentially fatal altercations (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2013:108), Violence interrupters use a variety of methods to detect conflicts, including "interrupting rumours", going to hospitals after shootings occur to prevent retaliation, paying attention to anniversaries and other important dates, being present at key locations, and being a resource to those in the community with information who are not comfortable with contacting the police (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2013:109). Mediations occur through many techniques, such as meeting one-on-one with aggrieved individuals, hosting small group peace-keeping sessions to foster diplomacy between groups, bringing in a respected third-party to dissuade further violence, creating cognitive dissonance by demonstrating contradictory thinking, changing the understanding of the situation to one which does not require violence, allowing parties to air their grievances, dispelling any misunderstandings, conveying the true costs of using violence, and buying time to let emotions cool down (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2013:109). Interrupting an on-going conflict before it becomes lethal cuts off a chain of events that are commonly known as retaliations (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2013:109). Importantly, it also prevents the exposure of others in the community to the potentially violent act, thus inhibiting transmission of the behaviour and perpetuation of the norm (Butts et al., 2015:2).

Methodology

The overall aim of the research was to explore the nature of school violence and existing strategies used to combat it and then design an effective intervention strategy to reduce violence. The research objectives of the study were exploring the nature, extent, causes and consequences of violence in participating high schools, evaluating the effectiveness of current strategies used to reduce violence in schools, investigating other strategies that can be applied by each stakeholder in violence reduction, and designing, implementing and evaluating an action research project to reduce school violence. Participatory action research (PAR) was considered a relevant method as it fosters participation of the community itself and is closely aligned to the Cure Violence method, which also requires active community participation. PAR can be said to seek understanding of the world and changing it. The specifics of an outcome are unknown as it is developed with participants. Reason and Bradbury (2001:1) emphasise the centrality of participation: PAR is "a participatory, democratic process... it seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in pursuit of a practical solution to issues of pressing concern to people." The first phase in PAR is the planning or investigatory phase and the development of the intervention, the implementation is the action phase, while reflection is the evaluation of the action. According to Lesha (2014:379), action research (AR) is a spiral process which includes problem investigation, taking action and finding facts on the result of the action. This process repeats, incorporating improvements in the next cycle. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Durban University of Technology. Psychological support was arranged prior to the start of the study, should a need arise. As the research was primarily aimed at creating constructive solutions to challenges, it was considered that there was no possibility of danger. The study included training, discussions and problem-solving. The researchers collaborated with the school, relevant nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the community.

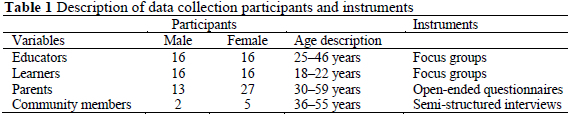

The study was conducted in the township of Umlazi in KwaZulu-Natal. To achieve the first objectives of the study data were collected in the following ways: open-ended questionnaires were distributed to parents, interviews were held with community members, and focus group discussions were held with educators and learners. Table 1 shows the description of the participants and data collection instruments used to collect the data.

For the purpose of this study, two schools were selected - one for base data and the second for the AR component. The research comprised two overlapping components - the collection of data followed by the design, testing and evaluation of the intervention. The overlapping nature of the study was that data collection continued throughout, often informally.

The initial focus was on eliciting the ideas, perceptions and experiences of stakeholders with regard to school violence, followed by identifying the major issues and the respondents' perceptions of the nature, extent, causes and consequences of violence in high schools. The respondents were asked to give their views on the effectiveness of current strategies. To achieve the objectives of the study, we employed three data collection tools: focus group discussions were conducted in both schools - two for learners and two for educators with eight participants in each group; open-ended questionnaires were issued to 40 parents of learners in both schools (20 per school); and five in-depth interviews were conducted with community members for both schools - two for the first school and three for the second school. Field notes were taken while conducting interviews and focus group discussions in order to document participants' responses and note observations of what was transpiring in the process.

Following the initial data collection, the next phase was to identify an action team who would participate in developing and planning a test intervention that would be modelled on the participatory nature of the Cure Violence method. The Cure Violence model maintains that violence is learned behaviour and that it can be prevented by using disease control methods, identifying "disruptors", empowering outreach workers to resolve conflicts non-violently and shifting perspective away from calling violent offenders "bad" people. Instead, regarding them as people with health problems that need help. A total of eight stakeholders - two learners above 18 years of age from Grade 11 classes, two educators, two parents and two community members were identified to be outreach workers. They formed a team called We Care (WC). WC's main objective was to brainstorm and to learn how to peacefully block the transmission of violence. Training for the WC group was also offered to School Peer Educators (SPEs). The SPEs is the existing school structure consisted two educators (one male and one female) and six learner volunteers from all grades (Grades 8-12, irrespective of gender and age). SPEs operated following the guidance of their code of conduct that was administered by the school. Their aims and responsibilities included building unity among learners in the school, addressing the needs of all learners in the school, keeping learners informed about events in the school and in the school community, encouraging good relationships within the school between learners and educators, and between learners and non-teaching staff, encouraging good relationships within the school between educators and parents and establishing fruitful links with other schools. However, on our arrival at the school, SPEs were less effective and operational. Hence, the School Management Team suggested that we should work with this structure as a way of capacitating them further. They admitted SPEs' limitations in the dealing with school violence and reduction strategies. SPEs and WC subsequently worked as sister bodies.

Both training sessions were conducted over 4 days. The training programme curriculum included anger and conflict, conflict resolution and mediation, paraphrasing, reflecting feelings, and understanding thoughts, feelings and actions. Non-violence and peace studies were discussed. Participants correlated the concept of peace with words such as humanity, tolerance, morality, and diversity. The core element of the training was based on how to control anger in order to avoid conflict. Most importantly, the training included how to control anger and how to resolve conflict in a non-violent manner. The Cure Violence model was discussed to equip individuals with the ability to treat violence as a transmittable disease.

Findings and Discussion

Exploration of the Nature, Extent, Causes and Consequences of Violence

Exploration is the act of searching for the purpose of discovering information, accomplished in this study by obtaining responses from

• four focus group discussions, two groups per school (one for educators and one for learners) with eight participants per group;

• 40 open-ended questionnaires from parents and

• five in-depth interviews with community members. Summarised responses from the focus group discussions, questionnaires and interviews are presented in Table 2.

Participants' responses on the causes of violence were grouped into the various themes and are presented in Table 3.

Common Forms of Violence in Schools

It was found that several types of violence originated outside the school premises. Some forms of violent behaviour such as stealing and vandalism were learned in families and communities beyond the school premises. This confirmed the need for the community to be involved in solutions; they could work with schools to take action against such external violence. Cases where learners stole each other's items such as bags, calculators, instruments or even school textbooks which they have all received from the school, were prevalent in these schools. While there were no cases of educators stealing from learners, suspicions of learners stealing from educators were stated. The participants' responses on the forms of violence are presented in Figure 1.

Consequences of School Violence

Participants pointed out the negative impact of school violence on learners, educators, parents, the education system, and the community at large. When the impact of school violence was discussed, all participants were very emotional and referred to previous incidents which they had encountered. They were worried about the number of physical incidents which lead to injuries or even death, and psychological incidents such as the high rate of school drop-outs, poor results, low self-esteem, which often results in poor learner-to-learner relationships, stress, and depression. They supported each other in saying that school violence destroyed the education system. These consequences are presented in Figure 2.

Effectiveness of Interventions

The two schools in this study, in collaboration with the DBE, were reported to have measures in place to minimise violence. One school reported that they were using a 3-part structure: SPEs, the school counsellor and the NGO, Star for Life, while the other school relied on motivating learners in the morning assembly before praying and going to the classrooms. Other programmes included those developed by the DoE such as Stop Rape, School-Based Crime Prevention, Management of Physical Violence, War Room and Dealing with Substance Abuse in response to the high rate of school violence. Strategies to reduce school violence were introduced as early as 2001, but the problem still existed in 2019.

During the data collection, data showed that participants favoured punitive measures over corrective ones. Data analysis also indicated that stakeholders perpetrated violence unintentionally because they did not understand what violence constituted.

Intervention

Intervention is characterised by the design and development of purposive change strategies. Following data collection, an action team (AT) was formed to discuss possible interventions to fight school violence. The AT decided to form a group, We Care (WC), with the objective to block the transmission of violence from one person to another. The group was presented with the Cure Violence model strategies: interrupting transmission directly, identifying and changing thinking of potential transmitters, and changing group norms regarding violence. The outcomes of the resulting discussions are presented below.

Interrupting transmission directly

WC participants brainstormed different techniques on how to locate potentially lethal on-going conflicts and mediating conflicts, interrupting transmission directly, interrupting conflicts, blocking transmission, changing the potential transmitter, mentoring individuals and changing the norm of a group. They acknowledged that most learners, parents and community members did not know that some of their actions constituted violence, hence they committed violence unintentionally. They committed themselves to start a programme that would educate people about violence and spread the gospel of peace to save lives. Their main function was to block the transmission of violence from one person to another by defusing potentially fatal altercations.

Identifying and changing the thinking of potential transmitters

WC members trained and capacitated SPEs on how to resolve conflict in a non-violent way and how to break the cycle of school violence. The training focused on how to identify and change the thinking of potential violence transmitters. On completion of the training programme, which included conflict mediation techniques, SPEs were empowered to locate potentially lethal on-going conflicts and respond with a variety of conflict mediation techniques, both to prevent imminent violence and to change the norms around the perceived need to use violence.

Changing group norms regarding violence

The training received by the WC and subsequently the SPE included empowering the community to change the norms of accepting and encouraging violence. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2013:110) explain that at the heart of Cure Violence's effort to change community norms is the idea that the norms can be changed if multiple messengers of the same new norms are consistently and abundantly heard.

Detecting and interrupting potential violent conflicts

WC and SPEs agreed to work hand in hand, where SPEs would mediate minor cases within the school and refer major cases which involved parents and community members to WC for intervention. They used specific methods to locate potentially lethal situations and responded with a variety of mediation techniques. They clustered different types of abuse, based on the suspected type, into five categories, namely, violent cases - surface injuries, bruises or burns; physical abuse - aggression, withdrawal, jumpiness or being fearful; neglect - hunger at school, fatigue, listlessness, begging and stealing; sexual abuse - lower school engagement and achievement, exhibiting sexually provocative behaviour or becoming promiscuous; and drug abuse - increase in aggression or irritability, changes in attitude, lethargy, a lack of hygiene or withdrawal from friends.

On 30 November 2016, the WC group, together with SPEs, were formally launched at the school as two structures that would work together to assist in school management. The two structures were divided as follows: SPEs worked with internal components of the school (i.e. educators and learners), and WC worked with external components of the school (i.e. parents and community members). The WC group was introduced as the structure which would try to interrupt violence outside the school environment, especially in learners' homes. SPEs were a well-known structure but the school emphasised that they would introduce the new role of teaching learners how to minimise and resolve conflicts peacefully.

Treatment for individuals at the highest risk for involvement in violence

The Cure Violence model aims to shift the perspective away from calling violent offenders "bad" people towards regarding them as people with health problems who needed help. The WC group divided their services into three categories: assist high risk learners who intend to reject violence, help learners who are the victims or perpetrators of violence, and assist parents or community members who are the perpetrators of violence.

These three categories are expanded upon in the next section.

High risk learners who intend to reject violence

The WC group consulted with high risk learners multiple times, conveying a message of rejecting the use of violence and assisting them to obtain needed services such as drug abuse counselling or referral to rehabilitation centres, depending on the level of alcohol and drug intake. WC consulted the local Drug Rehab Centre for the terms of referring learners to them.

Dealing with learners who are the victims or perpetrators of violence

SPEs and WC developed their plans of intervention depending on the nature of the cases. Different strategies were applicable to different cases, whether victims or perpetrators. For suspected perpetrators, SPEs documented a learner's suspicious actions before approaching them. The motive was to ascertain that the incident was recurring rather than being concerned about actions which were temporary. Repeated signs allowed the SPEs to approach a learner. WC obtained the information from SPEs prior to approaching a learner. SPEs and WC gave social support such as counselling to the victims and perpetrators of school violence. However, they established a working partnership with the SAPS, the local rehab centre, the local Childline Family Care and the local clinic for learners' referral. Psychological support was often necessary and professionals were therefore involved by prior arrangement.

Dealing with parents or community members who are the perpetrators of violence

WC visited parents or family members who were identified as perpetrators of violence. Depending on the nature of a case, some parents were visited while others were called to the school. One example of a visit was when WC decided to visit the family of a boy who had killed another with the intention of providing support and educating them about possible ways which they could use to block the transmission of violence. They introduced the concept that violence needed to be treated like a contagious disease which needed to be cured before it spread to other people. They warned a mother that her young children might model what they saw and become infected with violence as well. To summarise their experiences on all the home visits, the following points prevailed: parents can act as abusers and parents are not always aware that their actions constitute violence. Another point was that they may know that their children are being abused but are not able to act for various reasons such as financial dependence on the abuser, or fear of punishment or beatings by the abuser, having no other place to go to, and fears and problems regarding custody and maintenance.

WC were mindful of the fact that curing learners without support from their homes or community members was similar to the situation of someone who received an antibiotic but continued mistreating an open wound that was continually re-infected. WC are currently using their observations during home visits to formulate the education and training programme to convince people to reject the use of violence. They also discussed the cost and consequences of violence and taught alternative responses to different situations. They started to work with the people involved or most likely to be involved in violence, namely the parents of the identified learners. They used different platforms to change the way that parents and community members thought and behaved, as indicated in the next section.

Group and community norm change

WC engaged parents and community members aiming to convey the message that violence was harmful to everyone, that it was unacceptable and that it had to be stopped. To achieve their goal, they spread information in order to change behaviour and norms and taught methods of reducing violence. They used the knowledge acquired to communicate the message. They started doing door-to-door visits with the parents identified by SPEs, and participated in community events such as local councillor community meetings, school parents' meetings and school parents' consultations. For learners, they relayed the message in different forms such as consultations, open speeches at assembly, plays, and poetry and songs, where possible.

Outcomes

The outcomes of the Cure Violence model as an intervention strategy were evaluated. The WC and SPE groups were imparted with valuable knowledge during this study - knowledge that they would be able to use in years to come in the school and in the surrounding communities. It must be noted that during the study we concentrated on two high schools as the means of testing possible solutions to school violence. It is not possible to generalise the success of the intervention strategy to all South African schools, however, the outcomes indicate that curing violence before it was transmitted to other stakeholders did show noticeable results in KwaZulu-Natal. The possibility exists of widening the sample to more than the two schools in the sample. On our follow-up visit, the WC and SPE groups reported that they had arranged a Violence Awareness Day on 27 September 2017. Their theme was based on the Cure Violence context: "I refused to be transmitted with the violence disease, and you?" They also reported that they were very active in dealing with many cases involving parents. Two cases managed by the WC and SPE groups from February 2017 to September 2017 are described in the next section. The details have been modified to ensure anonymity.

Case 1: Child battery

The case was reported on 9 February 2017. It was reported that a mother of a 14-year-old girl in Grade 9 often projected her unhappiness on the girl and blamed the girl for her predicament. The mother often said that if the girl had not been born she would not be suffering so much. The abuse started at a very early age; at 6 years of age the girl had to be placed in the care of a children's home. However, she missed her mother and lied about being sick in order to be taken back home. Her mother discovered that she had lied about being ill and beat her for this. The girl was living with physical and emotional abuse on a regular basis. Her body was covered in old and new bruises. The girl told the WC group that she wished to commit suicide. SPEs referred her to the local clinic for medical treatment, and to Childline Family Care for social care. The examination report revealed that the child had marks over her whole body from being beaten with a belt, scratch marks at the back of her left hand, and fork stabs at the back of her right hand. While SPEs worked very closely with Childline Family Care to assist the child, WC started the process of visiting the mother of the child with the aim of educating her about violence. At first she was reluctant to open up to the group but on the third visit, she trusted them and started talking. She explained that she fell pregnant at the age of 16 and that her boyfriend then dumped her. She left school to look after the baby and suffered severely. She relayed that the most painful part of the entire ordeal involved seeing her former classmates living luxurious lives while she was very poor, unemployed and staying in an informal settlement. She would become furious when she saw her child, because she believed that the child robbed her of the life of which she once dreamed. WC invited a social worker to provide her with counselling. They explained the impact of the violence on her and her child. Their family visit sessions ended in July 2017 after unifying both the mother and the child. The child was observed not to have any new scars and seemed happier than before.

Case 2: Threats of assault

On 3 May 2017, a 17-year-old girl in Grade 9 reported being emotionally abused by her mother. Her mother threatened to kill her, chop up her remains and then place her remains in a refuse bag outside the house of the girl's father. She reported that her mother claimed to be tired of taking care of her while the girl's father was busy with all the "bitches" in the township. She also reported that her mother deprived her of the right to go to church. Her mother and father were no longer in a love relationship. According to the girl, she was afraid of sleeping in the same room as her mother and they barely spoke to each other. SPEs made arrangements with Childline Family Care for therapy. WC visited the mother of the child who denied that she had ever said anything of that nature to the child, but admitted to have had minor differences with her daughter in other cases. She claimed to love her child and take care of her. She revealed that she hated the father of the girl because he was irresponsible. WC invited both parents to the school, which was the only neutral venue convenient for both of them. After a long discussion with both parents, they reached agreement of being responsible for their child.

Conclusion

The overall aim of the study was to explore the nature, causes and consequences of school violence, and to design an effective intervention strategy to reduce it.

One critical challenge that each school faced was working towards the achievement of a violence-free school. It was mentioned that fighting school violence required well-trained and experienced individuals who were capable of dealing with such violence. Therefore, each school should have such individuals to handle various cases of violence. Upon implementing the Cure Violence model, it became evident that it was effective. The study contributed to the participants' knowledge and to an improvement of their conflict-handling skills. The enthusiasm of those who were trained in the Cure Violence model provided hope for the future. Since the participants in the study were actively putting the model into practice in their community, it was predicted that the Cure Violence model would continue to be more effective in the investigated schools and communities. This study was based on the concept that full participation by the stakeholders was essential. The response of the participants and their ability to develop and carry out an intervention confirmed the validity of this concept. PAR, as a methodology, provided a framework for developing this study and for facilitating active involvement in a solution. We also noted that the SPEs were school-based organisations of which membership was determined by school management and was less effective than the WC. The difference may be argued to be that one was self-motivated while the other was externally motivated. This points to the importance of willing participation.

Our recommendation for schools is to adopt the Cure Violence model in order to have trustworthy violence interrupters (such as WC) to whom victims can open up. These individuals should be trustworthy in order to ensure the confidentiality of intimate secrets. SPEs and WC in the schools where the model was tested indicated their wish to introduce at least one school per year to the model to ensure its continuity. One author also volunteered to assist schools who wished to launch the model. We were very pleased to notice that WC did indeed adhere to their confidentiality policy and provided details of the above cases without supplying the contact information of the learners and their parents. With this study was demonstrated that it was possible to apply the Cure Violence model in a school, and therefore implies that other schools could also implement the model.

The Cure Violence model seeks to create individual and community level change in those communities where it is the norm for young people to carry guns. The model caters for more serious crimes, which makes it difficult to apply it in other situations with less severe crimes. The model also recommends the use of high-risk individuals who were once involved in serious crimes, such as ex-prisoners. Reform is very complicated to achieve. The Cure Violence model uses three steps, making it is very time-consuming to move people from one step to another and very difficult to add new members who have missed the training of some steps in the model. It is very complicated for outreach workers to get time to meet and attend to training sessions because the group is composed of diverse people with busy lifestyles. Therefore, the level of absenteeism in scheduled training was very high. The model needs funding to employ violence interrupters: if there is no funding it becomes a significant challenge in sustaining outreach workers. The safety of outreach workers in visiting perpetrators in different places (homes, prisoners, hospitals) is not guaranteed.

The DoE curriculum planners for life orientation should include topics such as responding to anger, responding in peaceful and positive ways, creative and positive conflict resolutions skills and conflict avoidance as early as in the Grade R curriculum. Each school should have people to handle various violence cases. These people should be trustworthy in order to ensure the confidentiality of their victims' secrets.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to Doctor Sylvia Kaye (my supervisor); Professor Geoff Harris (co-supervisor); Bonginkosi Ngidi (my husband); Nonsindiso and Anele (my daughters); the KwaZulu-Natal DoE, which granted me the permission to conduct the research in public institutions; the principals, educators and learners of the two schools concerned; parents and community members; and WC and SPEs for making my study a success.

Authors' Contributions

LZN provided the data which was taken from her Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) study. SBK contributed to the discussions and analysis. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Bandura A 1971. Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press. [ Links ]

Bhana D 2013. Gender violence in and around schools: Time to get to zero. African Safety Promotion Journal, 11(2):38-47. [ Links ]

Burton P & Leoschut L 2013. School violence in South Africa: Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study (Monograph No 12). Cape Town, South Africa: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. Available at https://childlinegauteng.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Resources_School-Violence-Study-2012.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Butts JA, Wolff KT, Misshula E & Delgado S 2015. Effectiveness of the Cure Violence model in New York City. New York, NY: John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Available at https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1472&context=jj_pubs. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Centre for Health Equity Research Chicago 2018. What is a structural violence? Available at http://www.cherchicago.org/about/structuralviolence/. Accessed 10 November 2019. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2013. National strategy for the prevention and management of alcohol and drug use amongst learners in schools. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Drug%20National%20Strategy_UNICEF_PRINT_READY.pdf?ver=2014-07-18-150102-000. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa & South African Police Services n.d. Safety in education: Partnership protocol between the DBE and SAPS. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/SAFETY%20IN%20EDUCATION%20PARTENSRHIP%20PROTOCOL%20BETWEEN%20THE%20DBE%20AND%20SAPS.pdf?ver=2015-01-30-081322-333. Accessed 10 December 2019. [ Links ]

Draga L 2016. Infrastructure and equipment. In F Veriava, A Thom & TF Hodgson (eds). Basic education rights handbook: Education rights in South Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: SECTION27. Available at https://eduinfoafrica.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/basiceducationrightshandbook-complete.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Espelage D, Enderman EM, Brown VE, Jones A, Lane KL, McMahon SD, Reddy LA & Raynold CR 2013. Understanding and preventing violence directed against teachers: Recommendations for a national research, practice, and policy agenda. American Psychologist, 68(2):75-87. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031307 [ Links ]

Figueiredo CRS & Dias FV 2012. Families: Influences in children's development and behaviour, from parents and teachers' point of view. Psychology Research, 2(12):693-705. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539404.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Hendricks EA 2018. The influence of gangs on the extent of school violence in South Africa: A case study of Sarah Baartman District Municipality, Eastern Cape. Ubuntu: Journal of Conflict and Social Transformation, 7(2):75-93. [ Links ]

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council 2013. Contagion of violence: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13489 [ Links ]

Jansen G & Matla R 2011. Restorative practice in action. In V Margrain & AH Macfarlane (eds). Responsive pedagogy. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press. [ Links ]

Johnson S, Hodges M & Monk M 2000. Teacher development and change in South Africa: A critique of the appropriateness of transfer of northern/western practice. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 30(2):179-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/713657456 [ Links ]

Johnson SL, Burke JG & Gielen AC 2011. Prioritizing the school environment in school violence prevention efforts. Journal of School Health, 81(6):331-340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00598.x [ Links ]

Lesha J 2014. Action Research in education. European Scientific Journal, 10(13):379-386. [ Links ]

Maguire ER, Oakley MT & Corsaro N 2018. Evaluating cure violence in Trinidad and Tobago. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. [ Links ]

Meyer L & Chetty R 2017. Violence in schools: A holistic approach to personal transformation of at-risk youth [Special edition]. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 30(3):121-134. [ Links ]

Mkhize S, Gopal N & Collins SJ 2012. The impact of community violence on learners: A study of a school in the Swayimana rural area [Special edition]. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 1:38-45. [ Links ]

Mncube V & Steinmann C 2014. Gang-related violence in South African schools. Journal of Social Sciences, 39(2):203-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2014.11893283 [ Links ]

Ncontsa VN & Shumba A 2013. The nature, causes and effects of school violence in South African high schools. South African Journal of Education, 33(3):Art. #671, 15 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201503070802 [ Links ]

Netshitangani T 2018. School managers' experiences on strategies to reduce school violence: A South African urban school perspective [Special issue]. African Renaissance, 15(1):161-180. https://doi.org/1031920/2516-5305/2018/sin1a9 [ Links ]

Njuho PM & Davids A 2012. Patterns of physical assaults and the state of healthcare systems in South African communities: Findings from a 2008 population-based national survey. South African Journal of Psychology, 42(2):270-281. [ Links ]

Pahad S & Graham TM 2012. Educators' perceptions of factors contributing to school violence in Alexandra. African Safety Promotion Journal, 10(1):3-15. Available at https://www.ajol.info/index.php/asp/article/view/136062. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Ransford CL, Kane C & Slutkin G 2013. Cure violence: A disease control approach to reduce violence and change behavior. In E Waltermaurer & TA Akers (eds). Epidemiological criminology: Theory to practice. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203083420 [ Links ]

Reason P & Bradbury H (eds.) 2001. Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. Act No. 84, 1996: South African Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 377(17579), November 15. [ Links ]

Sanburn J 2016. Can we curb gun violence by treating it like a disease? Journal of Public Health, 188(1):23-24. [ Links ]

Sarwar S 2016. Influence of parenting style on children's behaviour. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 3(2):222-249. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2882540. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Singh GD & Steyn GM 2013. Strategies to address learner aggression in rural South African secondary schools. Koers - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 78(3):Art. #457, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/koers.v78i3.457 [ Links ]

Singh GD & Steyn T 2014. The impact of learner violence in rural South African schools. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 5(1):81-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09766634.2014.11885612 [ Links ]

Slutkin G 2013. Violence is a contagious disease. In DM Patel, MA Simon & RM Taylor (eds). Contagion of violence: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [ Links ]

Slutkin G, Ransford M, Decker B & Volker K 2014. Cure violence - An evidence-based method to reduce shootings and killings. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

South African Council for Educators 2011. School-based violence report: An overview of school-based violence in South Africa. Centurion, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.sace.org.za/assets/documents/uploads/sace_90788-2016-08-31-School%20Based%20Violence%20Report-2011.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

South African Police Service n.d. Crime statistics 2019/2020. Available at https://www.saps.gov.za/services/older_crimestats.php. Accessed 31 May 2021. [ Links ]

Toscano L 2015. Cure violence. Journal of Public Health:1 -49. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen CN & Maree JG 2010. Student teachers' perceptions of violence in primary schools. Acta Criminologica, 23(2):1-18. [ Links ]

Veriava F 2012. Rich school, poor school - the great divide persists. Mail & Guardian, 28 September. Available at https://mg.co.za/article/2012-09-28-00-rich-school-poor-school-the-great-divide-persists/. Accessed 31 May 2021. [ Links ]

Wachtel T 2016. Defining restorative. Bethlehem, PA: International Institute for Restorative Practices. Available at http://www.iirp.edu/pdf/Defining-Restorative.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022. [ Links ]

Received: 12 February 2020

Revised: 18 March 2021

Accepted: 28 May 2021

Published: 31 May 2022