Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 no.1 Pretoria feb. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n1a2025

ARTICLES

Effects of teachers' demographic factors towards workplace spirituality at secondary school level

Muhammad AslamI; Sohail MazharII; Muhammad SarwarIII; Abid Hussain ChaudharyIV

IInstitute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan aslamwatto@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Education, Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore, Pakistan

IIIUniversity of Okara, Pakistan

IVFaculty of Education, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

ABSTRACT

Workplace spirituality is recognised as the inner state of individuals and an aspect of their working life. In the study reported on here we aimed to unearth the effects of teachers' demographic factors (gender, age, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district) towards workplace spirituality in secondary schools. This study was a descriptive research and a cross-sectional survey research design was applied. The participants were 3,050 secondary school teachers. The participants were selected using stratified proportionate random sampling. The Workplace Spirituality Scale (WPS) developed by Petchsawang and Duchon (2009) was used along with a list of demographic variables to meet the study objectives. Different statistical techniques (t-test, mean, SD, one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis) were applied for data analysis. The results indicate that teachers were satisfied and agreed with the practices of workplace spirituality in secondary schools. Moreover, the results reveal that the teachers' demographic factors (gender, designation, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, teaching experience, and district) had significant effects on their workplace spirituality. From the results we recommend that the management of educational institutions should treat teachers equally and fairly without any discrimination for equal nurturing of workplace spirituality among teachers.

Keywords: demographic factors; secondary school teachers; spirituality; workplace spirituality

Introduction

The concepts of positive psychology, such as ethics, belief in a super force, integrity, mindfulness, trust, kindness, respect, sense of community and peace in organisations, inspiring employees, humanism, compassion, meaningful work and transcendence construct a new paradigm which is called workplace spirituality. Spirituality in the workplace is recognised as an aspect of the individual's work life, or the individual's inner state, which is developed and measured by performing meaningful work in the workplace (Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Petchsawang & Duchon, 2009).

This emerging concept of workplace spirituality holds a very important place in modern organisations. The concept of spirituality, previously prohibited in organisations, is now gradually being researched and accepted in modern organisations. Therefore, the progressive trend of workplace spirituality in management and behavioural sciences is becoming an important aspect for the success of organisations. Moreover, its worth in other than management and behavioural sciences is gradually increasing regardless of prevailing criticism and hesitations (Azad-Marzabadi, Hoshmandja & Poorkhalil, 2012).

Findings of various studies show that enhancing and developing workplace spirituality in organisations provide various advantages and benefits including improving trust, creativity, commitment, honesty, ethics, accountability, job satisfaction, motivation, integrity, sharing, involvement, and decreasing absenteeism, conflict, stress and turnover among employees (Burack, 1999; Delbecq, 1999; Freshman, 1999; Marques, Dhiman & King, 2005; Milliman, Czaplewski & Ferguson, 2003; Wanger-Marsh & Conley, 1999).

Therefore, the state of workplace spirituality in organisations has been contemplated by researchers, supervisors and administrators for the satisfaction and motivation of workers and customers (Rastgar, Jangholi, Heidari & Heidarina, 2012). The promotion of workplace spirituality and an increasing self-respect and confidence among employees lead to increased performance, satisfaction, commitment and efficiency (Karakas, 2010).

Currently, the necessity of research on workplace spirituality in organisations is increasing due to its emerging importance. Workplace spirituality creates stability and loyalty in workers and increases confidence, interest and enthusiasm (Beikzad, Yazdani & Hamdollahi, 2011). In addition, the role of spirituality in the workplace is contributory in that it provides civilization for society, perfection for organisations and obligations in the working environment (Mitroff, 2003).

The discrimination among teachers with regard to their demographic differences creates disparity in their workplace spirituality practices. Breytenbach (2016) states that workers' demographic have a significant effect on their level of workplace spirituality. The main focus of this study was on the current status of workplace spirituality among teachers with regard to their demographic factors.

Literature Review

The word "spirituality" derives from the Latin word "spiritus" that is about the metaphysical aspect of things like breath, soul and air. Spiritus is regarded as a fundamental aspect of living things that provides energy and spirit to the physical body. This means that spirit is an energy, drive and power that inhabits individuals in life when they are breathing and wakeful. Spirituality relates to consciousness, meaningful work, teamwork, mindfulness, thinking processes and connection with a super force and ultimate reality (Karakas, 2010). Zinnbauer, Pargament and Scott (1999) define spirituality as an energy and a fascinating power of life, which encourages an individual to a particular ending and a self-transcendent purpose.

The term "workplace spirituality" has different meanings in different academic disciplines, which makes is challenging to find a comprehensive definition (Tischler, Biberman & McKeage, 2002). Some scholars state that workplace spirituality is the core component of organisational culture (Daniel, 2010; Leigh, 1997). Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2003) describe workplace spirituality as a part of organisational culture which builds and increases workers' sense of transcendence, feelings of happiness, engagement with co-workers and work performance through organisational standards and ethics.

Kolodinsky, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2008) state that workplace spirituality can be categorised on three levels, namely, individual, organisational and societal level. Individual level workplace spirituality relates to personal spiritual ideas, feelings, beliefs and values in a specific workplace. Organisational level workplace spirituality relates to spiritual ideas, feelings, beliefs and values of individuals in an organisation. Societal level workplace spirituality relates to spiritual thoughts, feelings, beliefs and values of individuals about relationships with other members of society.

Mitroff and Denton (1999a) state that workplace spirituality is related to increasing meaningful work among employees, building teamwork, and creates balance between values of employees and organisational values. Petchsawang and Duchon (2009) describe workplace spirituality as building compassion with co-workers, exercising a state of mindfulness for increasing meaningful work that facilitates transcendence.

Gotsis and Kortezi (2008) describe workplace spirituality as a training of mindfulness, individual perfection, transcendence and gladness among workers that is recognised in several academic disciplines.

Breytenbach (2016) investigated the effect of several demographic variables on levels of individual spirituality, organisational spirituality and spirit at work. She found that gender and ethnicity had an effect on individual spirituality, that gender and organisational environment had an effect on organisational spirituality, and that experience and religious attachment had an effect on spirit at work.

Furthermore, Van der Walt and De Klerk (2015) found, through a quantitative approach and cross-sectional survey design, that several respondents' demographic variables have an effect on personal and organisational spirituality. Moreover, they found that several diversity factors (education, gender, religious affiliation) within a multicultural environment and across organisational cultures and contexts impacted personal and organisational spirituality.

Dimensions of workplace spirituality

Saks (2011) states that workplace spirituality is described differently by different scholars according to their context and culture. The experts on this notion connect it with various dimensions and concepts such as connectedness with society, organisation and oneself (Mitroff & Denton, 1999b), inner state of individual life, meaningful and purposeful work, teamwork (Ashmos & Duchon, 2000), personal fulfilment, organisational values, inner self, and engagement with organisation (Pawar, 2009). Likewise, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2003) indicate organisational beliefs, organisational values and connectedness. Furthermore, Liu and Robertson (2011) propose the dimensions of workplace spirituality as interconnection with a super force, co-workers, environment, and nature. However, according to literature, the common dimensions of workplace spirituality are meaningful work, compassion, inner state, mindfulness, sense of community, and transcendence. The focus of this study was on the dimensions of workplace spirituality projected by Petchsawang and Duchon (2009), namely, transcendence, compassion, meaningful work, and mindfulness.

Compassion

Compassion is a feeling developed for others: care, sympathy, support and understanding their suffering to provide a solution or relief. It is developing awareness and a desire to do good for others (Petchsawang & Duchon, 2009). Barsade and O'Neill (2014) surveyed around 3,200 employees from different organisations. The findings show that more compassion experienced within a workplace resulted in improved performance, commitment, accountability, overall job satisfaction, engagement, and teamwork which ultimately reduced stress, absenteeism and conflict in the workplace.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a state of being conscious of happenings around us and to be aware at all times. A mindful person is free from distractions and is a person who lives in the present and does not wander about past or future predicaments (Petchsawang & Duchon, 2009). Mindfulness is a friendly attention and mental presence in the workplace. Mindfulness improves attentional stability, attentional control, attentional efficiency, cognitive capacity, cognitive flexibility, positive emotions, hope, confidence, and self-regulation of behaviour (Good, Lyddy, Glomb, Bono, Brown, Duffy, Baer, Brewer & Lazar, 2015).

Meaningful work

Meaningful work is a sense of feeling that the person is working on something that is aligned with what he or she wants to achieve in life. Meaningful work gives a sense of joy, happiness and excitement. It is a means of expressing one's own inner self at work (Petchsawang & Duchon, 2009). Meaningful work contributes towards individual and organisational purposefulness, commitment, independence, control, engagement, accomplishment, proficiency, growth, mastery, self-realisation, and achievement in the workplace (Fairlie, 2011).

Transcendence

Transcendence explains a sense of connection with a higher power that gives one experiences of joy or bliss at work. Transcendence is a spiritual term and not a religious term that includes connectedness to God (Petchsawang & Duchon, 2009). Transcendence contributes towards widespread connectedness, enjoyment, limitless purpose, unity among individuals, and emotional closeness of employees in the workplace (Lace, Haeberlein & Handal, 2017).

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

Ashmos and Duchon (2000) indicate that organisations work according to doctrines of rational systems which create a situation for nurturing workplace spirituality. Workplace spirituality implies a humanistic approach in organisations. The humanistic approach had its origins in humanistic psychology (McGuire, Cross & O'Donnell, 2005). Alvesson (1982) states that the humanistic approach in organisations enhances workers' personal improvement and self-actualisation. He termed this phenomenon as "humanistic organization theory", which highlights the use of workers' different motivational strategies and personal development as a method of organisational management. This concept emphasises humanistic values such as confidence, a sense of community, unity, teamwork, self-realisation and development of organisational goals.

Melé (2003) states that organisational theory focuses on managerial aspects of organisations such as planning, organising, leading and controlling. However, he states that all managerial functions are performed by human resources for enhancement of individuals' as well as organisational performance. The presence of these humanistic elements creates the culture of the organisation. Scholars state that organisational culture relates to values, ethics, beliefs and informal practices, like trust, kindness, respect, sense of community, humanism, compassion and integrity among employees of an organisation, which creates an organisational culture (Barney, 1986; Schein, 1984). Researchers also mention that workplace spirituality is a component of organisational culture. Furthermore, it has been claimed that workplace spirituality is about establishing programmes and policies in organisations with the purpose of improving organisational values such as engagement, unity, integrity, fairness, teamwork, employees' commitment, confidence and fulfilment (Daniel, 2010; Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Leigh, 1997).

Secondary school teachers' demographics (gender, age, nature of job, qualification, marital status, designation, experience and constituency [district]) differ. Due to these differences, they are treated differently and unfairly in the workplace and as a result their experiences of workplace spirituality in schools differ. The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of teachers' demographics (gender, age, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district) on workplace spirituality in secondary schools. The objectives of the study were to

1) investigate the status of workplace spirituality in secondary schools

2) explore the effects of teachers' demographic factors (gender, age, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district) on workplace spirituality in secondary schools.

Methodology

Research Design

The study was quantitative research based on a positivist research paradigm. A cross-sectional survey design was used to investigate the effects of teachers' demographic factors on workplace spirituality in secondary schools.

Sampling

The participants in this study were teachers from secondary schools. There are a total of 36 districts in the Punjab province, Pakistan. The sample was 3,860 (1,880 male and 1,980 female) teachers. This sample was selected from 38,600 teachers from nine randomly selected districts. Ten teachers from each of 386 schools from nine districts were selected as participants. The sample was selected through stratified proportionate random sampling. We listed nine strata/subgroups on the basis of nine selected districts. Ten per cent proportionate samples were randomly taken from each stratum.

Instrument and Procedure

Petchsawang and Duchon' s (2009) WPS was used for data collection. This scale comprises four dimensions (mindfulness, compassion, transcendence and meaningful work). The questionnaire consisted of two sub-sections: the first section of the questionnaire covered the participants' demographic information and the second section covered the 22 WPS statements. Respondents responded to these statements on a 1 to 6 level Likert scale indicating the status of opinion as (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree, and strongly agree). A pilot study was conducted to validate the scale. Factor analysis was applied using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22 AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) to confirm the dimensionality, reliability and validity of Petchsawang and Duchon's (2009) WPS on a sample of 400 public school teachers. The validated instrument was used to collect data from the participants. Data collection was done personally and with the assistance of the administration of the School Education Department to ensure the maximum response rate. Three thousand and fifty questionnaires were returned, which was a response rate of 79%.

Data Analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS 22 software as well as t-tests, mean, standard deviation, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc analysis statistical techniques were used.

Results

The data analysis, results and findings of the study are discussed in this section.

Table 1 represents the demographic distribution of the sample. The total sample in this study consisted of 3,050 teachers.

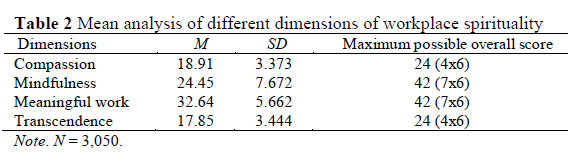

Table 2 represents the mean analysis of the different dimensions of workplace spirituality. It indicates that compassion recorded the highest mean value (M = 18.91/4 = 4.73). Mindfulness had the lowest mean value (M = 24.45/7 = 3.50). Transcendence (M = 17.85/4 = 4.46) and meaningful work (M = 32.64/7= 4.66) recorded medial mean values among all four dimensions of workplace spirituality. The results reveal that three dimensions of workplace spirituality recorded above the scale of somewhat agree (4.0) and below the scale of agree (5.0). Only mindfulness scored below the scale of somewhat agree (4.0). It reveals that teachers were more satisfied and agreed with the dimension of compassion compared to mindfulness, meaningful work and transcendence. The second and third important dimensions in workplace spirituality according to the participants were meaningful work and transcendence respectively. Mindfulness was considered the least important dimension of workplace spirituality.

An independent sample t-test was applied to determine the difference in the perceptions of male and female teachers about workplace spirituality. The results in Table 3 show that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of male and female teachers about workplace spirituality. It was concluded that teachers from the different genders practiced workplace spirituality differently.

An independent sample t-test was applied to determine contract and permanent teachers' perceptions on workplace spirituality. The results in Table 4 show that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of contract and permanent teachers on workplace spirituality. It was concluded that contract and permanent teachers practiced workplace spirituality differently.

An independent sample t-test was applied to determine married and unmarried teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality. The results in Table 5 show that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of married and unmarried teachers on workplace spirituality. It was concluded that married and unmarried teachers practiced workplace spirituality differently.

A one-way analysis of variance was applied to determine teachers' perceptions on workplace spirituality in terms of age. The analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality in terms of their age (see Table 6). Furthermore, a post hoc analysis was also performed to determine whether there was a difference between the two groups. The results of the post hoc analysis indicate that there was no significant difference in the teacher's perceptions with regard to the age groups (21-30, 30-40, 40-50, 50-60 years). This implies that teachers from all age groups thought similarly about workplace spirituality.

A one-way analysis of variance was applied to determine the teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality in terms of academic qualifications. The analysis revealed that there was a significant difference in teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality in terms of their academic qualifications (see Table 7). Furthermore, a post hoc analysis was also performed. The results of the post hoc analysis indicate that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers with regard to academic qualifications (Matric/FA, BA, MA/MSc and MPhil/PhD). It was concluded that the teachers with different academic qualifications thought differently about workplace spirituality.

A one-way analysis of variance was applied to determine the teachers' perceptions on workplace spirituality in terms of designation. The analysis reveals that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers about workplace spirituality in terms of their designation (see Table 8). Furthermore, a post hoc analysis was also performed to determine further differences between the two groups. The results of a post hoc analysis indicate that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers in the designation of PST/ESE and EST/SESE. It was concluded that the teachers from different designations thought differently about workplace spirituality.

A one-way analysis of variance was applied to determine the teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality in terms of teaching experience. The analysis reveals that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers about workplace spirituality in terms of their teaching experience (see Table 9). Furthermore, a post hoc analysis was performed to further determine any differences between the groups. The results of post hoc analysis indicate that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers with different years of teaching experience (0-5, 5-10, 10-20, and above 20 years). It was concluded that teachers with different years of teaching experience thought differently about workplace spirituality.

A one-way analysis of variance was applied to determine the teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality in terms of district. The analysis reveals that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers about workplace spirituality in terms of their districts (see Table 10). Furthermore, a post hoc analysis was performed to determine any further differences between the two groups. The results of the post hoc analysis indicate that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of teachers based on their district (Okara, T.T. Singh, Pakpatan, Bahawalnagar, Rawalpindi, Vehari, Sheikhopura, Bahawalpur, and Lahore). It was concluded that the teachers from different districts thought differently about workplace spirituality.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of teachers' demographic factors (gender, age, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district) on their perceptions of workplace spirituality in secondary schools. The results indicate that there were significant differences in the perceptions of teachers regarding workplace spirituality in terms of their demographic variables. It was indicated that demographic variables gender, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district significantly affected individuals' perceptions about workplace spirituality. These results support the findings of Kinjerski and Skrypnek (2006) who found that there was a significant difference in teachers' perceptions about workplace spirituality related to their demographic variables. Likewise, Cavanagh and Bandsuch (2002) found that there was a significant difference in employees' perceptions about workplace spirituality related to their demographic variables. Kerwar and Jaiswal (2018) also found that participants' demographics significantly influenced their perceptions on workplace spirituality. Likewise, Breytenbach (2016) conducted a study in South Africa and determined that several respondent demographic variables impacted levels of individual spirituality, organisational spirituality and spirit at work. Furthermore, Van der Walt and De Klerk (2015) conducted a study in African organisations and found that several respondent demographic variables effected personal and organisational spirituality.

Contrary to this, Chakraborty, Kurien, Singh, Athreya, Maira, Aga, Gupta and Khandwalla (2004) found no significant differences in employees' perceptions about workplace spirituality related to their demographic variables in terms of compassion, mindfulness, meaningful work and transcendence. Thompson (2000) found that there were no significant differences in the perceptions of teachers about workplace spirituality related to their demographic variables. Furthermore, it was identified that respondents' demographic factors had no effect on perceived status of workplace spirituality.

On the whole, the results of our study seem to suggest that the participants (teachers in secondary schools in Punjab, Pakistan) were treated differently in the workplace based on their demographics. This resulted in them perceiving workplace spirituality differently.

Conclusion and Further Suggestions

The results of this study indicate that there were significant differences in the perceptions of teachers regarding workplace spirituality in terms of their demographic variables (gender, nature of job, academic qualification, marital status, designation, teaching experience, and district). Therefore, it can be concluded that demographic variables significantly influence individual perceptions about workplace spirituality. The reason for this is that teachers were probably treated differently in the workplace resulting in their different perceptions of workplace spirituality in public secondary schools in Punjab, Pakistan.

We recommended that a school's administration should create an environment in which teachers of all demographic statuses are treated equally and fairly to minimises discrimination among secondary school teachers in order to result in equal development of workplace spirituality. Furthermore, teachers should share their daily experiences and practices of compassion, mindfulness, meaningful work and transcendence in their schools to develop workplace spirituality. We suggested that further studies on workplace spirituality with different organisational variables should be conducted. Future studies could also be conducted at different levels of educational organisations and in different organisations. Finally, we recommended that the management of educational institutions should treat teachers equally and fairly without any discrimination in order to build workplace spirituality among teachers.

Authors' Contributions

Muhammad Aslam conducted the research reported on here under the supervision of Professor (Prof.) Doctor (Dr) Abid Hussain Chaudhary. Sohail Mazhar and Muhammad Sarwar contributed in data collection, statistical analysis and writing of article. All four authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. This article is based on the doctoral thesis of Muhammad Aslam.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alvesson M 1982. The limits and shortcomings of humanistic organization theory. Acta Sociologica, 25(2):117-131. [ Links ]

Ashmos DP & Duchon D 2000. Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(2): 134-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/105649260092008 [ Links ]

Azad-Marzabadi E, Hoshmandja M & Poorkhalil M 2012. Relationship between organizational spirituality with psychological empowerment, creativity, spiritual intelligence, job stress, and job satisfaction of university staff. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 6(2): 181-187. Available at https://iranjournals.nlai.ir/bitstream/handle/123456789/218353/3F4B4D25C78479EB48BF5E4F8364 7339.pdf?sequence=-1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Barney JB 1986. Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3):656-665. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1986.4306261 [ Links ]

Barsade SG & O'Neill OA 2014. What's love got to do with it? A longitudinal study of the culture of companionate love and employee and client outcomes in a long-term care setting. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(4): 551-598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839214538636 [ Links ]

Beikzad J, Yazdani S & Hamdollahi M 2011. Workplace spirituality and its impact on the components of organizational citizenship behavior (Case study: Staff of Tabriz five educational zones). Journal of Educational Administration Research Quarterly, 3(9):61-90. Available at https://jearq.riau.ac.ir/article_488_9cfc9734d64d21d376f37ef673332c25.pdf?lang=en. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Breytenbach C 2016. The relationship between three constructs of spirituality and the resulting impact on positive work outcomes. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. Available at https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/60501/Breytenbach_Relationship_2016.pdf?sequenc e=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Burack EH 1999. Spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4):280-292. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282126 [ Links ]

Cavanagh GF & Bandsuch MR 2002. Virtue as a benchmark for spirituality in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 38:109-117. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015721029457 [ Links ]

Chakraborty SK, Kurien V, Singh J, Athreya M, Maira A, Aga A, Gupta AK & Khandwalla PN 2004. Management paradigms beyond profit maximization. Vikalpa, 29(3):97-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920040308 [ Links ]

Daniel JL 2010. The effect of workplace spirituality on team effectiveness. Journal of Management Development, 29(5):442-456. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039213 [ Links ]

Delbecq AL 1999. Christian spirituality and contemporary business leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4):345-354. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282180 [ Links ]

Fairlie P 2011. Meaningful work, employee engagement, and other key employee outcomes: Implications for human resource development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(4):508-525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422311431679 [ Links ]

Freshman B 1999. An exploratory analysis of definitions and applications of spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4):318-329. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282153 [ Links ]

Giacalone RA & Jurkiewicz CL 2003. Toward a science of workplace spirituality. In RA Giacalone & CL Jurkiewicz (eds). Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. [ Links ]

Good DJ, Lyddy CJ, Glomb TM, Bono JE, Brown KW, Duffy MK, Baer RA, Brewer JA & Lazar SW 2016. Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. Journal of Management, 42(1):114-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003 [ Links ]

Gotsis G & Kortezi Z 2008. Philosophical foundations of workplace spirituality: A critical approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(4):575-600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9369-5 [ Links ]

Karakas F 2010. Spirituality and performance in organizations: A literature review. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1):89-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0251-5 [ Links ]

Kerwar M & Jaiswal G 2018. Role of spirituality in organisational performance measure by ANCOVA. International Research Journal of Management, Sociology & Humanity, 9(12):40-64. [ Links ]

Kinjerski V & Skrypnek BJ 2006. A human ecological model of spirit at work. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 3(3):231-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766080609518627 [ Links ]

Kolodinsky RW, Giacalone RA & Jurkiewicz C 2008. Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2):465-480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9507-0 [ Links ]

Lace JW, Haeberlein KA & Handal PJ 2017. Five-factor structure of the Spiritual Transcendence Scale and its relationship with clinical psychological distress in emerging adults. Religions, 8(10):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100230 [ Links ]

Leigh P 1997. The new spirit at work. Training & Development, 51(3):26-33. [ Links ]

Liu CH & Robertson PJ 2011. Spirituality in the workplace: Theory and measurement. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1):35-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610374648 [ Links ]

Marques J, Dhiman S & King R 2005. Spirituality in the workplace: Developing an integral model and a comprehensive definition. The Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 7(1):81-91. [ Links ]

McGuire D, Cross C & O'Donnell D 2005. Why humanistic approaches in HRD won't work. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16(1):131-137. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1127 [ Links ]

Melé D 2003. The challenge of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(1):77-88. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023298710412 [ Links ]

Milliman J, Czaplewski AJ & Ferguson J 2003. Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4):426-447. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310484172 [ Links ]

Mitroff II 2003. Do not promote religion under the guise of spirituality. Organization, 10(2):375-382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508403010002011 [ Links ]

Mitroff II & Denton EA 1999a. A spiritual audit of corporate America: A hard look at spirituality, religion, and values in the workplace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mitroff II & Denton EA 1999b. A study of spirituality in the workplace. Sloan Management Review, 40(4):83-92. [ Links ]

Pawar BS 2009. Individual spirituality, workplace spirituality and work attitudes: An empirical test of direct and interaction effects. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(8):759-777. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730911003911 [ Links ]

Petchsawang P & Duchon D 2009. Measuring workplace spirituality in an Asian context. Human Resource Development International, 12(4):459-468. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860903135912 [ Links ]

Rastgar A, Jangholi M, Heidari F & Heidarina H 2012. An investigation on the role of spiritual leadership in organizational identification. Studies on General Management, 16:39-63. [ Links ]

Saks AM 2011. Workplace spirituality and employee engagement. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 8(4):317-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2011.630170 [ Links ]

Schein EH 1984. Culture as an environmental context for careers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 5(1):71-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030050107 [ Links ]

Thompson WD 2000. Can you train people to be spiritual? Training and Development, 54(12):18-19. [ Links ]

Tischler L, Biberman J & McKeage R 2002. Linking emotional intelligence, spirituality and workplace performance: Definitions, models and ideas for research. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(3):203-218. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940210423114 [ Links ]

Van der Walt F & De Klerk JJ 2015. The experience of spirituality in a multicultural and diverse work environment. African and Asian Studies, 14(4):253-288. https://doi.org/10.1163/15692108-12341346 [ Links ]

Wagner-Marsh F & Conley J 1999. The fourth wave: The spiritually-based firm. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4):292-302. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282135 [ Links ]

Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI & Scott AB 1999. The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality, 67(6):889-919. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00077 [ Links ]

Received: 19 April 2020

Revised: 26 November 2020

Accepted: 4 March 2021

Published: 28 February 2022