Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.42 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n1a2013

ARTICLES

Exploring working conditions in selected rural schools: teachers' experiences

Thabisile Nkambule

Curriculum Division, School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. thabisile.nkambule@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Even though quality education is important for the empowerment of individuals and development of society, some rural schools in South Africa continue to function amid tough conditions. Because little research on the topic exists, with this article I explore and identify teachers' experiences of the working conditions in rural schools in South Africa. A qualitative, descriptive and interpretive case study was used, and 5 schools were purposively selected as cases for the study, 2 primary and 3 secondary schools. Interviews and observations with 11 teachers provided insight into the difficult working conditions that teachers in some rural school need to contend with. Teachers in rural schools continue to experience difficult working conditions and due to their loyalty to their schools, they do not relocate to other schools. Dilapidated infrastructure, a lack of chalk boards, insufficient textbooks, among others, hamper teacher's working conditions and constrain their teaching. The participants in the study indicated that principals played a fundamental role in supporting and inspiring teachers who work under challenging conditions.

Keywords: learning; rural schools; teachers' experiences; teaching; working conditions

Introduction

Teaching conditions play an important role in the quality of teaching, learners' performance, and teachers' willingness to remain at a particular school (Ni, 2012; Raggl, 2015). It is generally accepted that supportive working conditions improve teacher efficacy and student achievement (Ladd, 2011; Sellen, 2016) and less supportive conditions lead to teacher attrition that undermines efforts to provide high-quality teaching to all learners (Kraft, Marinell & Yee, 2016; Marinell & Coca, 2013).

Researchers (Adedeji & Olaniyan, 2011; Brownell, Bishop & Sindelar, 2018; Du Plessis & Mestry, 2019; Stelmach, 2011) agree that rural schools face a unique set of working and social conditions such as attracting and retaining qualified teachers, especially for mathematics and science, information communications technology (ICT) and English. Learners travel long distances to school on foot and multigrade teaching and learning is almost the norm. There is scarcity of research in South Africa that explores how such conditions influence teaching and teachers in rural schools. With this article I seek to contribute to research on rural education in South Africa by exploring rural teachers' place-based experiences of their teaching and working conditions.

Understanding the Working Conditions of Teachers and Teaching

Teachers and the working conditions they contend with play a key role in achieving quality education for all (Bloch, 2009; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2008). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD, 2019) teacher reviews have shown that working conditions are crucial for the attractiveness of the teaching profession, as well as for retaining well qualified teachers. Johnson (2006) posits that working conditions are influenced by the organisational structure and the social, political, psychological, and physical features of the work environment. The New York State United Teachers (NYSUT, 2014:34) refers to the teaching conditions as the "school's systems, relationships, resources, environments and personnel that affect a teacher's ability to achieve instructional success with their students." In this article I explore teachers' experiences of the working conditions in rural schools. Adedeji and Olaniyan (2011) observe that the working condition of teachers in rural schools across sub-Saharan Africa place them at a disadvantage in providing adequate teaching activities. The National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 indicates that problems with the working conditions of teachers in South African rural schools needed urgent attention (National Planning Commission [NPC], 2012:49).

Although education is considered useful for national development in Africa, working conditions of teachers in rural schools have not changed or improved much (Opoku, Asare-Nuamah, Nketsia, Asibey & Arinaitwe, 2020). In South Africa, researchers (Emekako, 2017; Hlalele, 2013; Langa, 2013) note the poor state of classrooms, a lack of visitation by provincial officers, and poor sanitary conditions as some factors that affect the working conditions of teachers and teaching in rural classrooms. Namibian working conditions for rural teachers are influenced by malnutrition among learners (that makes it difficult for them to concentrate and grasp the content being taught), learner absenteeism, lack of motivation, and a lack of parental support and guidance (Namwandi, 2014; Shikalepo, 2020). According to Nganga and Kambutu (2017), Kenyan rural teachers' working conditions include learners sharing textbooks, which forces teachers to write summaries on chalkboards for learners to copy into their summary books, and a scarcity of teachers specialising in maths and science to ensure quality teaching and learning. The above-mentioned difficult working and social conditions indicate that rural teachers work hard to provide better education for the learners and yet still find themselves falling short.

Conceptual Framework

In this study we use Mason and Poyatos Matas' (2015) four main components of the capital model: human capital; social capital; structural capital; and positive psychological capital to identify and understand the working conditions of teachers and teaching in specific rural schools. Human capital refers to the professional knowledge and skills and opportunities for continuing professional development (Mason & Poyatos Matas, 2015), because teaching in rural schools requires teachers who have the requisite knowledge, understanding and commitment to remain in these schools. Social capital refers to the development of a school culture where teachers accept themselves as equal members and work together as a team (Mason & Poyatos Matas, 2015). The school leadership creates a favourable working environment by organising professional development and encouraging collaboration between teachers.

Structural capital refers to the existence of basic facilities in schools, such as appropriate classrooms and teaching materials, to motivate teachers to provide quality education in rural schools (Mason & Poyatos Matas, 2015). Lastly, psychological capital refers to personality traits such as commitment, resilience, and the desire to work as teachers despite the lack of incentives, to provide better education for learners. Understanding teachers' perspectives on the working conditions in rural schools is important, seeing that little research on this topic exists. In this study we explored the following questions:

a) How do teachers perceive the working conditions of teaching in South African rural schools?

b) What are the teachers' experiences of the working conditions in their schools?

c) How do these conditions enhance and/or constrain teaching and teachers in the schools?

Methodology

This study was exploratory in nature and I used a qualitative, descriptive, and interpretive case study to gain insight into the "multiplicity of teachers' perspectives which are rooted in a specific context" (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003:24). Five schools, two primary and three secondary schools, were selected as cases for this study. The underlying philosophy of a single case study is "not to prove but to improve" (Stufflebeam, Madaus & Kellaghan, 2000:283) and contribute to the existing knowledge on rural teachers' working and social conditions of teaching and learning.

In the study we used "semi-structured individual interviews and a mixture of episodic structure (asking the interviewees to draw on specific experiences, concrete cases) and narrative structure (reflecting on their experiences over time, exploring the representation that they formed of their experiences)" (Flick, 2000:75-92). It was important to focus on what the teachers said about the specific teaching conditions in their schools. The follow-up questions emerged from participants' responses, (as they emphasised specific aspects), strengthening the original interview questions, and I gained a nuanced understanding of the lived experiences through participants' detailed descriptions and explanations.

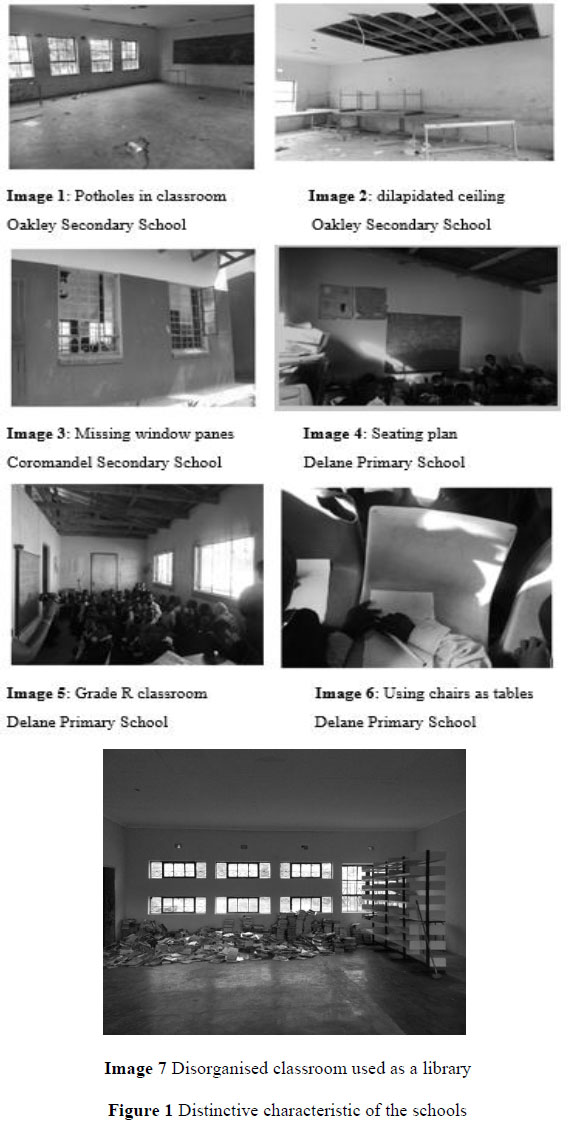

Permission was sought from the various schools to collect data. The interviews were conducted after school, and each interview session lasted between 45 minutes and an hour, varying from session to session. Data collection lasted 12 days as unexpected teacher unioni meetings took place, and some teachers attended workshops presented by the Department of Education. With the participants' permission, all interviews were audio-recorded to ensure that all information was captured accurately. I also used unstructured observations and video-recorded the physical conditions of the buildings, the available educational resources such as laboratories, libraries, and textbooks (see images in Figure 1 as examples showing the physical conditions at the schools. All schools' names are pseudonyms). The intention of this observation was to understand the reality of some of the school setting to contextualise teachers' responses during the interviews.

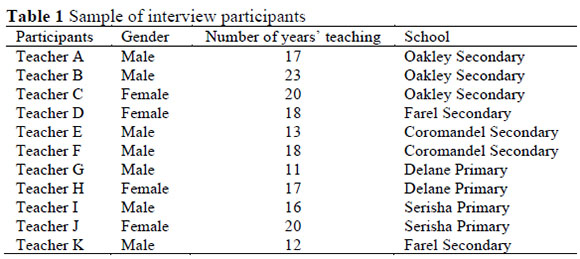

The participating schools were purposively selected, and the teachers were selected based on their teaching experience at rural schools. Table 1 outlines the teachers' number of teaching years in the different schools. Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2011) assert that the researcher decides what needs to be known and sets out to find people to provide the information. I therefore approached teachers that had participated in the Wits rural teaching practice project, because they were born in and worked within the Zembe community. Of the 15 teachers whom I approached, only 11 agreed to participate in the study - four participants from the two selected primary schools and seven participants from the three selected secondary schools. Consent forms were distributed to participants to complete before the interviews were held (see Table 1 for participants). To adhere to ethical considerations, I used letters of the alphabet to represent the teachers and pseudonyms to represent the schools. The schools were situated in different locations within the Zembe community and had distinctive characteristics (see Table 1 for the schools).

Data organisation and analysis began immediately after collection, guided by Tuckman and Harper's (2012) statement that data collection and analysis processes are inseparable in qualitative research. Each interview transcript was read several times to ensure thorough and accurate work, while coding responses to identify, analyse and report emerging patterns of the teachers' experiences and the influences on the teaching conditions, and identified themes. I then extracted quotations that were critical for each theme to enhance the teachers' descriptions and narrations of their experiences in own words; "capturing in their language and letting them speak for themselves" (Singleton & Straits, 1999:349). I used a small sample to explore and understand the teachers' experiences in detail and not to generalise the findings, which Carter and Fuller (2015) identify as a unique strength of qualitative studies.

Results

"... These Conditions have been with Us for a Long Time ..."

From the participants' responses I concluded that the working conditions in the schools have not been favourable, and that this situation had existed for a long time. The teachers got used to these conditions and lost all hope for change.

We have come to accept that it is like this; these conditions have been with us for a long time, will stay with us forever. You don't even think about them anymore, it's work as usual forever. I can't remember our school in good conditions anymore. (Teacher C: Oakley Secondary School)

... you get used to things you should not here mam,ii because the conditions are old, they have been here forever... (Teacher J: Serisha Primary School).

Even though the teachers were concerned about the lack of transformation in their schools, they have been committed to their work. Considering the number of years working in the schools, teachers have used their contextual and professional knowledge and skills to remain in rural schools. Despite the number of years in unchanged difficult working conditions, teachers' resilience and motivation was noted. Even though they acknowledged that the conditions would not normalise, they knew that teaching had to continue for the betterment of the community and the learners.

Furthermore, teachers were op the opinion that the working conditions for teaching were out of their control.

... there's nothing we can do with such conditions, nothing at all as teachers. We are expected to teach in any condition, whether good or bad . change is taking very long in rural areas (Teacher A: Oakley Secondary School).

... we just don't know what to do any more. If you don't have anything else, you stay in these conditions ... The government doesn't care about our schools here. If they don't see it, it doesn't exist; you can talk all you want. (Teacher E: Coromandel Secondary School)

... do feel left out most of the time. We really feel forgotten in our rural schools, and still have to perform in these dangerous conditions ... (Teacher G: Delane Primary School).

The teachers were aware of the continuing marginalisation of rural schools as they were expected to teach and perform under dangerous working conditions. Such reflection represents positive personal character and understanding of the "reality" of the context. These findings are similar to those described by participants in other studies (Emekako, 2017; Hlalele, 2013; Langa, 2013) in that provincial officials do not visit rural schools to assess their needs. Given the teachers' exposure to difficult working conditions, it is understandable that teachers have lost confidence in the provincial government. Balfour, Mitchell and Moletsane (2008:102) ask: "Why is it that, 17 years after the demise of apartheid, South Africa and its education system are still plagued by seemingly insurmountable challenges, with no change in sight for those who need it most, especially those who live, work, and learn in rural marginalised communities?" Such experiences in rural schools affect the provision of quality education, even though these teachers showed their commitment to provide better education - irrespective of the dangerous working conditions.

The "Appalling" and "Embarrassing" Working Conditions for Teachers and Teaching Teachers talked about their experiences of teaching conditions, to illustrate the lack of improvement, and their distress. The infrastructure, physical and teaching resources, constrained effective teaching and influenced the teachers' morale negatively. Teachers had to contend with the lack of staffrooms, libraries, chalkboards, and textbooks, which are important tools for efficient teaching. Hansen, Buitendach and Kanengoni (2015) posit that access to adequate resources has been problematic in South Africa, which affects teachers' motivation and enthusiasm for their jobs. Teachers reflected on the physical and teaching resources in the schools that influenced teaching and teachers:

The conditions are appalling. Can you imagine, we don't have a staffroom. Since I came here, it's been 15 years, still no staffroom. And 20 years later nothing has changed for us here (Teacher J: Serisha Primary School).

There are no chalkboards in some classes; it's pieces of chalkboards everywhere. I need to write while teaching ... but I can't. Teaching is about writing; [the] chalkboard is all we have here and this affects teaching and learning. The chalkboard is very important and now you don't have it, you have a small piece of it. It's all I ever know and now it's disappearing, I'm not sure how I will teach. Mr Zondo [not his real name] is also frustrated because he needs the whole chalkboard for maths, to show learners how to solve mathematics problems, but there's little left of it to use. Think of poetry; it needs to be analysed on the board, learners need to see how to do it, step by step. (Teacher A: Oakley Secondary School)

The staffroom is one of the important dedicated spaces for teachers to perform various professional duties such as marking learners' books, interacting and discuss ideas with colleagues, planning lessons and holding staff meetings. The lack thereof meant that teachers had to transform one of the classrooms and create a staffroom - in schools that do not have enough classrooms. This did not only constrain teachers but also teaching, because they did not have a place and space to prepare themselves before lessons. Hunter, Rossi, Tinning, Flanagan and Macdonald (2011:23) posit that a "staffroom not only functions as a physical space, but also a social, cultural and emotional space for teachers." Even though teachers did not have a place to interact with colleagues and destress after intense teaching, they were understanding and committed to serve the rural community and the learners.

The chalkboard is the centre of a classroom and important for teaching, especially if it is the only tool available to share knowledge. The lack of proper chalkboards slowed teachers because they could not talk and write on the board, to "allow students to keep pace with the teacher" (Muttappallymyalil, Mendis, John, Shanthakumari, Sreedharan & Shaikh, 2016:591). The "pieces" of chalkboards constrained teachers' teaching activities, e.g. drawing diagrams, doing calculations, and analysis of literature. The findings are consistent with Phiri and Mulenga (2020) that most of the chalkboards in rural schools are dilapidated and sometimes it is difficult to find any chalkboard in a school.

Textbooks are of the most important teaching tools and provide various sets of visuals and readings in rural schools. Milligan, Koornhof, Sapire and Tikly (2019:536) state that textbooks "save time, give direction to lessons, guide discussion, make teaching 'easier' and better organised." While this might be the case, it was difficult for the English and Sepediiii teachers to teach effectively without sufficient textbooks, because it meant engaging with unprepared learners. The following comment is illustrative:

Mam, just the thought of it, it's embarrassing... I can't ask them [learners] to do more reading at home, because what will they read? There's insufficient textbooks; they are always underprepared. Literature is one of the sections to teach learners independent and critical reading, thinking and writing, but now how can you do that when you don't have enough textbooks? I have three classes to teach, we move with the textbooks to the next class every time. This affects my teaching because I end up doing everything for them. We don't want to teach them to be dependent, but the conditions are not easy because they make us teach in a particular way. (Teacher F: Coromandel Secondary School)

Textbooks play a significant role in language teaching and the preparation of learners to speak a second language (English in this instance). Teachers' concerns about the insufficient textbooks to encourage a culture of reading, is understandable in a context where learners' reading and analytical skills and performance in international and local tests continues to be poor.iv Paxton (2015), in a study conducted in the Eastern Cape, identified that teachers struggled to teach without textbooks, because learners were unable to prepare before the lesson. The lack of sufficient textbooks not only constrained teachers' pedagogy but also the teaching of important skills such as thinking, speaking, and writing, which are important to promote independent learners (Makalela, 2015; Trisha, 2016). Although the lack of sufficient textbooks is a national problem in South Africa, it is worse in rural schools as there are no alternative places like community libraries for learners to access additional reading matter.

Furthermore, learners from Grade Rv to secondary school suffer in distressing classroom situations that do not stimulate learning and children's active participation. Gordon and Browne (2014) state that classrooms are considered the heart of each day' s world for the children and the teachers, and children should be allowed to feel safe and motivated to learn.

Everything is not right, the conditions are never right for teaching and learning. There are small kids here . falling ceilings, potholes in classrooms. It is our responsibility if something happens to them ... we had to use the kitchen, changed the kitchen to a classroom for grade R children. They are overcrowded ... three kids share one table, others have to use chairs as tables to write. They have to learn to write with good table and chairs . how can they learn to write in such a challenging situation? (Teacher H: Delane Primary School)

... some learners don't have chairs ... the chair is supposed to be four-legged, but it's three, it's a balancing game. It's crazy, think of a car with three wheels, how can it move because it's supposed to have four wheels? Others don't have tables, are writing on their laps. For how long will you write on your lap? For the whole day and all subjects? (Teacher C: Oakley Secondary School)

While it is unthinkable to teach and learn in a classroom with "potholes" and falling ceilings, the well-being of children is the teachers' responsibility. The above description of classrooms indicates that the physical arrangement does not support comfortable teaching for teachers. The number of children and the existing dilapidated furniture prevent the appropriate and fundamental development of reading and writing skills, which are important to set the foundation in primary schools. Gerdes, Durden and Manning (2013) state that the arrangement of the physical environment of the classroom can have a big impact on teaching and learning. One secondary school teacher gave an interesting example of a three-wheeled car to create a picture of learners' real classroom conditions, which do not make learning exciting and limit active engagement in the classroom. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2006) highlights that when classrooms are characterised by the above inadequacies, they limit the child's right to learn, and it is thus unlikely that teachers can provide quality education.

The School Culture and the Teaching Conditions Although principals were neither the focus of or participants in the study, teachers identified them as enabling or constraining working conditions for teaching.

I think our principal is doing great. The teaching mood is great ... we follow from his steps, and communication is great and shows respect. The principal encourages us to do our best with the little we have, and we have been performing well under the circumstances. (Teacher D: Farel Secondary School)

It's not bad in our school. The conditions are favourable for teaching and learning, classes have proper teaching and learning resources. Our principal makes sure that we talk about the conditions; he promises to attend to them so that we focus on our work. You don't have to worry about the conditions as a teacher; my role is to make sure that learners learn successfully. (Teacher K: Farel Secondary School)

Inspiring and supportive leadership encourages teachers to focus on their teaching, irrespective of inadequate infrastructure. It does not mean that the working conditions are not "real", but that effective principals can promote positive teachers' attitudes by promoting collegiality. These findings are consistent with social capital which states that school leaders who create favourable environments can have a positive impact on teacher retention (Mason & Poyatos Matas, 2015).

Some principals' lack of support within challenging working conditions constrained teaching and teachers.

The principal is not supportive; the staff is divided; lack of respect; it's actually not a good condition to work in our school. We have been complaining that we don't get information on time from the department; the principal stayed with the information until the last minutes. I needed to attend a physical science workshop and he informed me a day before. Mr Ndawe [pseudonym] was supposed to attend a maths workshop; and the principal didn't inform him on time. The school is chaotic, we take the lead from him. Other conditions depend on our leadership, how effective he is ... our condition of leadership is not supportive, and you can only do so much as a teacher. (Teacher F: Coromandel Secondary School)

It is crucial that teachers have opportunities for professional development, especially in a context where provincial officials rarely visit schools. Teachers' development is important to expose them to current trends in teaching, improve their skills and interact with colleagues within specialisations (Opoku et al., 2020). The relationship between the principal and the teachers constrained the working conditions as there was no support to enhance teachers' subject knowledge, which have been identified as scarce in rural schools. It is the principal who prevents professional development, thus influencing learners' performance. The findings show that even though schools are located within the same district and are exposed to the same socio-economic conditions, conditions depended on the nature of the principal's leadership and interaction with teachers.

Discussion

While quality education has been recognised as a basic human right for all, more work still needs to be done as rural schools continue to encounter difficulties in accessing quality education (Adedeji & Olaniyan, 2011; Balfour et al., 2008; Phiri & Mulenga, 2020). The results illustrate that even though rural teachers have been exposed to challenging teaching conditions, they remained committed and resilient despite poor working conditions. According to Mason and Poyatos Matas (2015:55) "teachers who choose to remain in rural schools have the requisite knowledge, understanding and commitment to remain in these schools." The teaching experiences in rural schools show that teachers have prioritised the provision of better education in spite of the difficult working conditions. These findings are different from those of other studies (Johnson, 2006; Kraft et al., 2016; Marinell & Coca, 2013) that indicate that less supportive working conditions lead to teacher attrition; instead, teachers' character led to teacher retention.

The findings in our study are consistent with those in research on the significance of the principals that encourage teacher development, create favourable environments for supportive teamwork, and promote respect and collaboration among teachers (Johnson, 2006; Mason & Poyatos Matas, 2015; Opoku et al., 2020). The combination of human, social and psychological capital plays an important role in teachers' decisions to stay at rural schools despite the challenging working conditions, because of commitment and shared goals to better the education in rural schools. Interestingly, the findings also show that even though teachers may constantly experience complications owing to the lack of proper chalkboards, insufficient textbooks, dilapidated classrooms, et cetera, leadership plays a positive role in ensuring success against all odds. On the other hand, at schools where the leadership does not address challenging working conditions, this negatively influences teachers' morale and willingness to work, owing to the unsupportive leadership.

If newly qualified teachers are to be encouraged to teach in schools with challenging working conditions, the authorities and policy makers need to take cognisance of the findings of this study. This is particularly important as the Initial Teacher Education programmes are encouraged to send their pre-service teachers to such schools for teaching practicum.

The findings should also encourage principals to constantly interact and encourage teachers working in challenging conditions to ensure that they remain at the school. The findings will also assist academics to understand the working conditions in rural schools and the teachers' experiences of such conditions.

Limitations and Conclusion

I acknowledge several limitations of this study. Firstly, the study did not include learners' perceptions of the teaching and learning conditions. Future studies could include learners' experiences in rural schools on whether and how such experiences influence their performance. Secondly, even though principals' contributions were mentioned by teachers, they were not included in the study. Principals' experiences could be included in future studies to gain insight into leaders' experiences of leading under difficult working conditions. Thirdly, the study focused only on rural schools located within a particular province; some rural schools located in different provinces have specific teaching conditions that influence them differently - something that could also be researched. In conclusion, the findings reveal the continuous challenges of teaching in rural schools, but teachers are not planning to leave the schools. The teachers' personality traits and loyalty make them resilient and help them focus on teaching and encouraging learners' successful performance. This highlights that employing teachers from rural areas could result in positive responses to challenging working conditions because they want to make a difference to the lives of others.

Notes

i . The South African Democratic Teachers' Union (SADTU) is the largest teachers' union in South Africa.

ii . The word "mam" is commonly used to address female teachers; a contraction of the word "madam."

iii. Sepedi is one of the nine official African languages in South Africa; the others are Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele, Tshivenda, Swati, Sesotho, Xitsonga and Setswana (SAlanguages.com, 2021).

iv . In the 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) results, South Africa was placed last out of the 50 countries that participated (Howie, Combrinck, Roux, Tshele, Mokoena & McLeod Palane, 2017).

v . In the South African school system there are four phases: the Foundation Phase, which starts with Grade R (reception year, or Grade 0) and lasts 4 years (up to and including Grade 3); the Intermediate Phase that starts in Grade 4 and lasts 3 years (up to and including Grade 6); the Senior Phase which consists of Grades 7 to 9 and concludes the so-called General Education and Training Band. The Further Education and Training (FET) Band includes Grade 10 to Grade 12 (3 years), thus concluding schooling education (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2021).

vi. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Adedeji SO & Olaniyan O 2011. Improving the conditions of teachers and teaching in rural schools across African countries. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: UNESCO: International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa. Available at www.uis.unesco.org/publications/teachers2018. Accessed 1 February 2021. [ Links ]

Balfour RJ, Mitchell C & Moletsane R 2008. Troubling contexts: Towards a generative theory of rurality as education research. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 3(3):95-107. Available at https://joumals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/139/49. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Bloch G 2009. The toxic mix: What's wrong with SA's schools and how to fix it. Cape Town, South Africa: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Brownell MT, Bishop AM & Sindelar PT 2018. Republication of "NCLB and the demand for highly qualified teachers: Challenges and solutions for rural schools". Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(1):4-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870517749604 [ Links ]

Carter MJ & Fuller C 2015. Symbolic interactionism. Sociopedia.isa, 1:1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/205684601561 [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2011. Research methods in education (7th ed). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2021. Education in South Africa. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/EducationinSA.aspx?gclid=CjwKCAjwxOCRBhA8EiwA0X8hizkOo-CpiuPZtFbZlstnA-fef_ochh8RKMbr_akUoQAX5JlYqDoabxoCrOcQAvD_BwE. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Du Plessis P & Mestry R 2019. Teachers for rural schools - a challenge for South Africa [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 39(Suppl. 1):Art. #1774, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1774 [ Links ]

Emekako RU 2017. A framework for the improvement of the professional working conditions of teachers in South African secondary schools. PhD thesis. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: North-West University. Available at http://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/31576. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Flick U 2000. Episodic interviewing. In MW Bauer & G Gaskell (eds). Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Gerdes JK, Durden TR & Manning LM 2013. Materials and environments that promote learning in the primary years. Available at http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cyfsfacpub. Accessed 16 April 2020. [ Links ]

Gordon AM & Browne KW 2014. Beginnings and beyond: Foundations in early childhood education (9th ed). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Hansen A, Buitendach JH & Kanengoni H 2015. Psychological capital, subjective well-being, burnout and job satisfaction amongst educators in the Umlazi region in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1):Art. #621, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.621 [ Links ]

Hlalele D 2013. Sustainable rural learning ecologies - a prolegomenon traversing transcendence of discursive notions of sustainability, social justice, development and food sovereignty [Special edition]. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 9(3):561-580. [ Links ]

Howie SJ, Combrinck C, Roux K, Tshele M, Mokoena GM & McLeod Palane N 2017. PIRLS Literacy 2016: South African Highlights Report. Pretoria, South Africa: Centre for Evaluation and Assessment. Available at http://www.shineliteracy.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/pirls-literacy-2016-hl-report.zp136320.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Hunter L, Rossi T, Tinning R, Flanagan E & Macdonald D 2011. Professional learning places and spaces: The staffroom as a site of beginning teacher induction and transition. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1):33-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.542234 [ Links ]

Johnson SM 2006. The workplace matters: Teacher quality, retention, and effectiveness (National Education Association [NEA] Best Practices Working Paper). Washington, DC: NEA. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED495822.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Kraft MA, Marinell WH & Yee DSW 2016. School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5):1411-1449. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216667478 [ Links ]

Ladd HF 2011. Teachers' perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2):235-261. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373711398128 [ Links ]

Langa PN 2013. Exploring school underperformance in the context of rurality: An ethnographic study. PhD thesis. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/9323/Langa_Phumzile_Nokuthula_2013.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Makalela L 2015. Moving out of linguistic boxes: The effects of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classrooms. Language and Education, 29(3): 200-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994524 [ Links ]

Marinell WH & Coca VM 2013. Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-part study of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools (Synthesis Report). New York, NY: Research Alliance for New York City Schools. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED540818.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Mason S & Poyatos Matas C 2015. Teacher attrition and retention research in Australia: Towards a new theoretical framework. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(11):45-66. [ Links ]

Milligan LO, Koornhof H, Sapire I & Tikly L 2019. Understanding the role of learning and teaching support materials in enabling learning for all. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(4):529-547. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1431107 [ Links ]

Muttappallymyalil J, Mendis S, John LJ, Shanthakumari N, Sreedharan J & Shaikh RB 2016. Evolution of technology in teaching: Blackboard and beyond in Medical Education. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 6(3):588-594. https://doi.org/10.3126/nje.v6i3.15870. [ Links ]

Namwandi D 2014. Rural learners taught by unqualified teachers. Namibian Sun. [ Links ]

National Planning Commission 2012. National Development Plan 2030: Our future - make it work. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at http://www.dac.gov.za/sites/default/files/NDP%202030%20-%20Our%20future%20-%20make%20it%20work_0.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

New York State United Teachers 2014. Teaching and learning condition matter: Key considerations for policymakers. Available at https://www.nysut.org/~/media/files/nysut/resources/2014/september/whitepaperteachinglearning.pdf. Accessed 22 April 2020. [ Links ]

Nganga L & Kambutu J 2017. Preparing teachers for a globalized era: An examination of teaching practices in Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(6):200-211. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1133010.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Ni Y 2012. Teacher working conditions in charter schools and traditional public schools: A comparative study. Teachers College Record, 114(3):1-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211400308 [ Links ]

Opoku MP, Asare-Nuamah P, Nketsia W, Asibey BO & Arinaitwe G 2020. Exploring the factors that enhance teacher retention in rural schools in Ghana. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(2):201-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1661973 [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2019. TALIS 2018 results (Vol. I). Paris, France: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en [ Links ]

Paxton C 2015. Possibilities and constraints for improvement in rural South Africa schools. PhD thesis. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town. Available at https://nicspaull.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/paxton-possibilities-and-constraints-for-improvement-in-rural-south-african-schools-final-incl-corrections.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Phiri D & Mulenga IM 2020. Teacher transfers from primary schools in Chama district of Zambia: Causes of the massive teacher exodus and its effects on learner's academic performance. Multidisciplinary Journal of Language and Social Sciences Education, 3(2):94-125. Available at https://library.unza.zm/index.php/mjlsse/article/view/233/241. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Raggl A 2015. Teaching and learning in small rural primary schools in Austria and Switzerland - Opportunities and challenges from teachers' and students' perspectives. International Journal of Educational Research, 74:127-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.09.007 [ Links ]

Ritchie J & Lewis J (eds.) 2003. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

SAlanguages.com 2021. Available at http://www.salanguages.com/. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Sellen P 2016. Teacher workload and professional development in England's secondary schools: Insights from TALIS. London, England: Education Policy Institute. Available at https://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/TeacherWorkload_EPI.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Shikalepo EE 2020. Challenges facing learning at rural schools: A review of related literature. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, IV(III):128-132. Available at https://www.rsisinternational.org/journals/ijriss/Digital-Library/volume-4-issue-3/128-132.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Singleton RA, Jr & Straits BC 1999. Approaches to social research (3rd ed). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Stelmach BL 2011. A synthesis of international rural education issues and responses. Rural Educator, 32(2):32-42. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ987606.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Stufflebeam DL, Madaus GF & Kellaghan T (eds.) 2000. Evaluation models: Viewpoints on educational and human services evaluation (2nd ed). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic. [ Links ]

Trisha AH 2016. A study on the role of textbooks in second language acquisition. BA thesis. Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University. Available at http://dspace.bracu.ac.bd:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10361/7627/12103043_ENH.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 28 February 2022. [ Links ]

Tuckman BW & Harper BE 2012. Conducting educational research (6th ed). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2008. Education for all global monitoring report 2009: Overcoming inequality - why governance matters. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2006. Global education digest 2006: Comparing education statistics across the world. Montreal, Canada: Author. [ Links ]

Received: 2 June 2020

Revised: 9 June 2021

Accepted: 22 July 2021

Published: 28 February 2022