Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41ns2a1905

The school organisational climates of well-performing historically disadvantaged secondary schools

Mgadla Isaac XabaI; Salome Kelly MofokengII

ISchool for Professional Studies in Education, Edu-Lead Niche, Faculty of Education, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa. ike.xaba@nwu.ac.za

IIGauteng Department of Education, Sedibeng West District, Sebokeng, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In the study reported on here we investigated the nature of the organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools. These schools were designated for Black learners during the apartheid era in townships and rural areas. Despite their "disadvantagedness", many of these schools have consistently performed well in the National Senior Certificate (NSC)ii for 3 consecutive years or more. The Organisational Climate Descriptive Questionnaire-Rutgers Elementary (OCDQ-RE) was administered to 1,050 teachers from these schools in the Gauteng Department's Sedibeng and Johannesburg South districts. Results reveal that although these schools are regarded as well-performing, their teachers perceived their organisational climates as closed with principal and teacher behaviours being closed. Teachers experienced very low engagement and above-average frustrated behaviour. An important consideration is that principals seemed to exhibit directive support, which seems to have led to teachers exhibiting features of engaged behaviour. The implication is for principals' capacity-building, which should include features of holistic school organisational behaviour and development. Furthermore, the Organizational Climate Descriptive Questionnaire for Secondary Schools (OCDQ-RS) should be validated for the South African school context.

Keywords: directive behaviour; engaged behaviour; frustrated behaviour; historically disadvantaged schools; intimate behaviour; leadership behaviour; school organisational climate; supportive behaviour; teacher behaviour; well-performing schools

Introduction

The concept "school climate" is derived from organisational climate and school effectiveness literature and research (Tubbs & Garner, 2008). For this reason, school climate is referred to as school organisational climate because the school is regarded as an organisation as it has all features typical of organisations. As an organisation, a school is concerned exclusively with teaching and learning (Theron, 2013). For this study, school organisational climate refers to teachers' perceptions and experiences of their school environments (Vos, Van der Westhuizen, Mentz & Ellis, 2012). This, Pretorius and De Villiers (2009) define as a relatively enduring, pervasive quality of the internal environment that influences teachers' behaviour and stems from their collective perceptions.

Hoy and Miskel (2005:185) define organisational climate as "the set of internal characteristics that distinguish one school from another and influences the behaviour of each school's members." Mentz (2013), typifying organisational climate as teachers' perceptions of principals' behaviour, describes it as teachers' experience of management aspects, which translates into their experience of school life and consequently, their behaviour. In this sense, Janson and Xaba (2013:138) construe organisational climate as "the team spirit in the school and social interaction between teachers and learners, between teachers and teachers [...]." Cohen, Pickeral and McClostey (2009) assert that a positive and sustained organisational climate promotes learner academic achievement and healthy development. Pretorius and De Villiers (2009:33), drawing from Hoy and Miskel (1987), surmise school climate as the "heart and soul of a school; psychological and institutional attributes that give a school its personality; [...] which describes their collective perceptions of routine behaviour and affects their attitudes and behaviour." For this reason, Tubbs and Garner (2008:18) point out that school climate is part of the school environment associated with attitudinal and affective dimensions and the belief systems and argue that "because values, attitudes, beliefs, and communications are adult focused behaviours, researchers primarily rely on participants' perceptions to measure school climate [...]."

Based on the foregoing exposition, and for purposes of this study, school organisational climate is defined as the manifestation of principal and teacher behaviour as they influence and are influenced by the internal characteristics of the school environment; and where this behaviour results in behavioural orientations that determine how they work together to achieve the school's goals.

Historically disadvantaged schools in South Africa face challenging circumstances, including inadequate educational resources, learner discipline problems, which at times culminate to violence and fatalities, teacher burn-out, overcrowded classes, lack of parental involvement and poor physical resources (Kane-Berman, 2018; Mofokeng, 2019; Ziduli, Buka, Molepo & Jadezweni, 2018:1). They often perform poorly, as is evident from poor NSC results (Nkosi, 2020) and experience challenges related to their locations - often located in townships, whereas departmental offices and officials are located mostly in towns, which results in inadequate support. Their location is a legacy of the apartheid dispensation, which segregated them according to ethnic groups inter alia, Zulus, Sothos and Xhosas. Consequently, their location resulted in challenges that include poor spatial planning, overcrowding and crime, high unemployment and poverty rates and lack of education resources.

Despite such challenges, a significant number of these schools consistently achieve good NSC results. This consistency cannot be a mere coincidence and implies that they possess factors facilitating good performance. In this regard, school organisational climate comes to mind, notably because organisational climate influences behaviour in organisations. To this end, the United States (U.S.) Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students (2016) asserts that a positive school climate leads to providing support that enables learners and staff to realise high behavioural and academic standards. In this sense, the organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged schools may influence teacher behaviour and by extension, learner behaviour, such that behavioural orientations result in consistent performance, which makes them to be characterised as well-performing schools. To this end, a positive school climate is regarded essential in promoting enduring behaviour fostering excellent results (Holloway, 2012; Lazridou & Tsolakidis, 2011; Pretorius & De Villiers, 2009; Tubbs & Garner, 2008; Vos et al., 2012). It must, however, be pointed out that these schools are characterised as well-performing because they consistently achieve NSC result above 60% (Department of Education, 2005).

A few studies on school organisational climate in South Africa were found. Three studies focused on primary schools (De Villiers, 2006; Motsiri, 2008; Vos et al., 2012) while one study focused on school climate as an enabling factor in an effective peer education environment (Moolman, Essop, Makoae, Swartz & Solomon, 2020). Studies focusing on school organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged schools could not be identified. With this study we sought to answer the question: How do teachers at well-performing, historically disadvantaged schools experience their school organisational climates? To this end, we intended to determine the organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools by:

• examining principals' and teachers' behavioural dimensions; and

• determining the types of their organisational climates.

Conceptual Framework

Hoy, Tarter and Kottkamp (1991) highlight five dimensions of secondary school organisational climates, grouped into principal and teacher behaviours, supportive and directive principal behaviour and engaged, frustrated and intimate teacher behaviour. Supportive behaviour is directed towards both the social needs and task achievement of the staff by being helpful, genuinely concerned about teachers and attempting to motivate them by using constructive criticism and setting an example through hard work. Directive behaviour, by contrast, is rigid, domineering and is directed at maintaining close and constant monitoring of all teachers and school activities to the smallest detail (Hoy et al., 1991).

Hoy et al. (1991) state that engaged behaviour reflects staff that are proud of the school, enjoy working with one another, are supportive of their colleagues and committed to the success of their learners. Frustrated behaviour is characterised by staff who feel burdened with routine duties, administrative paper work and excessive assignments unrelated to teaching. Intimate behaviour reflects a strong and cohesive network of social relations among the staff (Hoy et al., 1991). The interaction of the dimensions typifies school organisational climate into an open or closed climate. An open climate is characterised by open principal behaviour, which is reflected in genuine relationships with teachers through which the principal creates a supportive environment, encourages teacher participation and contribution and frees teachers from routine busywork so that they can concentrate on teaching. Open teacher behaviour is characterised by sincere, positive, and supportive relationships with learners, the school management team and colleagues' commitment to the school and success of learners (Holloway, 2012; Hoy et al., 1991).

According to Hoy et al. (1991), the closed climate is the antithesis of the open climate: where the principal and teachers simply go through the motions, with the principal stressing routine trivia and unnecessary busywork. Teachers respond minimally and exhibit little commitment to tasks. The principal's leadership is seen as controlling and rigid, unsympathetic and unresponsive and is accompanied not only by frustration and apathy, but also by suspicion and lack of respect for colleagues as well as the school management. Therefore, in closed climates, principals are non-supportive, inflexible, hindering and controlling and the staff is divisive, apathetic, intolerant and disingenuous.

The definitions of organisational climate highlight behavioural manifestations of organisational members as being dependent on how they experience the quality of their working life (Mentz, 2013). In this sense, organisational climate determines the behaviour of its members, and in the case of schools, how they conduct their teaching functions. The conceptualisation of the organisational climate of the schools is depicted in Figure 1.

We contend that the type of school organisational climate has an influence on teacher performance, and, therefore, it is important to gain a holistic view of the school organisational climate, in this case, well-performing historically disadvantaged schools. Moreover, as Lazridou and Tsolakidis (2011) point out, "climate has demonstrable influence on organisational effectiveness" (para. 4). Furthermore, the findings of this study could enable school stakeholders' school improvement efforts in South Africa and invoke academic discourse on school organisational climate as well as assist principals and policy makers to consider the importance of this construct. In this regard, even more variables can be explored including variables such as stakeholder engagement, relationships, school safety, school environments and infrastructure (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students, 2016). This study may also help to assess the suitability of the OCDQ-RS for the South African context.

With this study we sought to determine the organisational climate at well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools. The study was aimed at five organisational climate indicators determining how teachers perceived their schools' organisational climates, namely directive and supportive principal behaviours, engaged, frustrated and intimate teacher behaviour.

Method

Research Design

A quantitative, descriptive survey research design (Creswell, 2012) was used to examine the participants' perceptions regarding the behaviour of principals and teachers as indicators of organisational climate. This study is located within the positivist paradigm, which considers scientific explanation to be based on universal laws; aims to measure the social world objectively; and to predict human behaviour (Check & Schutt, 2012).

Population and Sampling

The population comprised teachers from historically disadvantaged secondary schools that had consistently performed well in the NSC examinations between 2015 and 2017, with pass rates of 60% and above without falling below their best average (Department of Education, 2005).

For convenience and accessibility, schools selected for the survey were from the Gauteng Department of Education's Sedibeng and Johannesburg South districts. The Department of Basic Education's school performance report indicated 30 schools that were consistently performing well (Department of Basic Education, RSA, 2018). This number was confirmed with the Institutional Support and Development Officers from the two districts. All teachers from these schools (N = 1,050) were surveyed and a return rate of 81.5% (856) questionnaires was attained.

Data Collection

Hoy et al.'s Organizational Climate Descriptive Questionnaire for Secondary Schools (OCDQ-RS) was used to investigate the schools' organisational climates by determining the behavioural dimensions of school principals and teachers.

The OCDQ-RS uses a four-point, Likert-type response scale indicating "rarely occurs", "sometimes occurs", "often occurs" and "very frequently occurs" and consists of 34 items covering the five behavioural dimensions identified earlier. The questionnaire was piloted to establish language relevance for the target population (Delport, 2002) with teachers (n = 20) who were not part of the final population.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

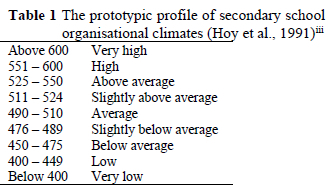

The scoring for the OCDQ-RS as detailed in Hoy et al. (1991), instructs firstly that the mean scores and standard deviations for each dimension are calculated. Secondly, the school subtest scores are converted into standardised scores with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100. This produces openness indices for principal and teacher behaviour and the openness index of schools' organisational climate. These indices are then compared with the prototypic profile of organisational climates of secondary schools used with the OCDQ-RS (Hoy et al., 1991). Finally, the standardised scores are converted into openness indices for each dimension to determine the school climate types. This is drawn from a table of categories ranging from high to low scores derived from the prototypic profiles of climates constructed using the normative data from a diverse sample of schools from New Jersey (Hoy et al., 1991) as depicted in Table 1.

The scores between 551 and 600 indicate a high to very high behaviour prevalence, while scores below 400 indicate a very low prevalence. It must, however, be pointed out that scores pertain to the New Jersey high schools against which scores in these study were compared. This is because there is currently no comparative data for South African secondary schools. Nevertheless, Pretorius and De Villiers (2009) cite Anderson's (1982) and Lindahl's (2006) assertions that the Organizational Climate Descriptive Questionnaire (OCDQ) is one of the major school climate instruments that has been widely recognised by climate researchers and reviewers and possess the "tremendous heuristic value" of the instrument, which has promoted a broad-based interest in elementary and secondary school climate.

In our study, the organisational climates of the schools were determined using the scoring guidelines with the assistance of the statistical consultancy services at the North-West University.

Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire registered a reliable Cronbach's alpha index of 0.75 overall (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Of the five behavioural dimensions, four had acceptable Cronbach reliability indices while one, intimate behaviour, had a low reliability index of 0.297, and an inter-item correlation score of 0.096. Consequently, the dimension was omitted from the analysis. This was also with the understanding that the dimension was not germane to task accomplishment but only to social interactions or needs.

Ethical Standards

To comply with ethical standards, approval was given by the Research Ethics Committee of the North-West University, the Gauteng Department of Education, the school governing bodies, and the principals of schools. Teachers were requested to complete the OCDQ-RS, and thus, their informed consent was elicited, and participation was voluntary. Participants were informed of their rights, including refusing to participate, confidentiality and non-exposure to risk or harm.

Results

Demographic data are first presented. The results of the OCDQ-RS are then presented - principal and teacher behaviours. The findings on the behavioural analyses necessitated analyses of data on organisational climate dimensions and on the types of organisational climates, followed by correlations between organisational climate dimensions.

Demographic Data

There were more female (52.1%) than male (47%) respondents. The three largest age groups were 36 to 45 years (34.8%), 26 to 35 years (20.6%), and 46 to 55 years (24.9%). Most respondents had teaching experience of between 6 and 25 years (70.7%). Respondents seemed adequately qualified, with the majority (85.7%) having bachelors and honours degrees, while 9.3% had teaching certificates and diplomas, all of which are set qualification standards for teachers. Respondents were mostly from formal township settlements (90.0%), and from schools with enrolments of above 1,000 learners (65.7%). Of the sample, 81.2% were teachers, 13.3% were heads of department, and 5.3% were deputy principals. The latter ranks were included because they had teaching responsibilities, in contrast to principals, who generally do not have teaching responsibilities.

Principal Behaviour

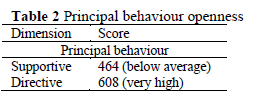

Mean scores were calculated for principal and teacher behaviour and were used to standardise the aggregate scores to determine principal behavioural dimensions and the general openness for the schools' climate. As alluded to earlier, these score were compared to the New Jersey high school scores as directed by Hoy et al. (1991). Table 2 depicts the scores for teachers' perceptions of their principals' openness behaviour.

Scores in Table 2 indicate that teachers perceived principals' openness behaviour as very highly directive (608) and below average supportive (464).

Directive principal behaviour is typified by rigid and domineering control, where the principal closely and constantly monitors all teachers and school activities, down to the smallest detail. Because very high principal directive behaviour was indicated, it was important to analyse frequency counts on items for this dimension (Table 3).

As depicted in Table 3, overall, respondents felt that their principals were not highly directive. For example, a minority (41.4%) reported that it often or very frequently occurred that teacher-principal meetings were dominated by the principal. Furthermore, the majority (60.7%) reported that it rarely or sometimes occurred that the principal ruled with an iron fist and another majority (63.8%) indicated that it rarely or sometimes occurred that the principal was autocratic while a majority of 60.3% similarly indicated that it rarely or sometimes occurred that principal talked more than they listened. Notably, less than half (47.0%) reported that principals closely checked teacher activities.

It is also noteworthy that just over half of the respondents felt that principals monitored everything teachers did and supervised teachers closely. These responses possibly explain perceptions of very high directive principal behaviour.

Although overall, supportive principal behaviour was below average, frequency analyses of items on this dimension (Table 4) are notable because respondents perceived their principals as supportive.

Respondents largely perceived their principals as exhibiting supportive behaviour. As depicted in Table 4 above, the majority of teachers felt that their principals set an example by working hard themselves, complimented teachers, went out of their way to help teachers, and looked out for the personal welfare of the staff.

However, perceptions on items such as the principal explains his/her reason for criticism to teachers; is available after school to help teachers when assistance is needed; and uses constructive criticism were perceived as rarely or sometimes occurring, which could explain the overall below-average supportive behaviour.

Teacher Behaviour

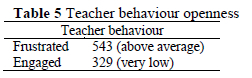

Teacher behaviour scores are depicted in Table 5.

Table 5 indicates that frustrated teacher behaviour scored above average (M = 543.36) and engaged teacher behaviour very low (M = 329.68), which indicate very low engaged behaviour.

Teacher frustrated behaviour refers to staff who feel burdened with routine duties, administrative paper work and excessive assignments unrelated to teaching, including poor relations with their colleagues.

Table 6 depicts the frequency analysis on teacher frustrated behaviour.

Perceptions on respondents' behaviour revealed above average frustrated behaviour. The majority of respondents indicated they were rarely frustrated. However, the majority of them indicated that frustrating behaviour rarely or sometimes occurred. For example, more than half indicated this on items such as the mannerisms of their colleagues become annoying (72.5%); assigned non-teaching duties are excessive (64%); routine duties interfere with the job of teaching (61.6%); teachers interrupt other members who are talking in meetings (72.2%); administrative paperwork is burdensome at their schools (55.6%) and notably, they often had too many committee requirements (57.5%).

Engaged behaviour reflects staff that are proud of the school, enjoy working with one another, are supportive of their colleagues and committed to the success of their learners. Table 7 depicts descriptive data on teacher engaged behaviour.

Overall, engaged teacher behaviour scored very low. On items of this dimension, teachers' perceptions were rather mixed. It is noteworthy that on some matters pertaining to teachers themselves, the majority reported engaged behaviour. For example, more than half were proud of their schools; helped and supported each other, enjoyed working at their schools and respected the personal competence of their colleagues.

Notably, fewer than half of the respondents (45.8%) reported that their morale was high. They, however, were engaged in some matters involving learners. For instance, a small majority (52.4%) reported being friendly with learners.

In contrast, most teachers (61.5%) reported rarely or sometimes spending time after school with learners who had individual problems. Even more disconcerting, is the majority's (63%, 63.3% and 66.8%) perception that at their schools the representative council of learners had an influence on school policy, learners solved their problems through logical reasoning and learners were trusted to work together without supervision respectively.

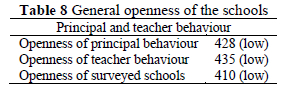

Types of School Organisational Climates The types of school organisational climates of the respondents' schools were determined from the openness indices of the schools as derived from the principals' and teachers' behaviour (Table 8).

Teachers perceived their own behaviour as very low on engagement and above average frustrated. The principal and teacher behaviour openness were perceived as low (428 and 435) respectively. These openness scores were used to determine schools' climate profiles. The schools' openness scored 410, interpreted as low and translating into closed school organisational climates.

As is typical of research findings generating interest in other areas, the findings from the descriptive data generated interest in whether the dimensions of the schools' organisational climates had any influence on each other. To this end, correlations were used to determine if there were any relationships between the organisational climate dimensions themselves.

The Correlations of the Dimensions between Principal and Teacher Behaviour

Pietersen and Maree (2016) define a correlation coefficient as a measure of the strength of a linear relationship between two variables, and whether it has a statistically significant difference from zero. This means that the correlation coefficient links two variables, and is always between +1 and -1. Gogtay and Thatte (2017) and Salkind (2014) interpret the correlation coefficients between 0.8 and 1 as very strong, between 0.6 and 0.8 as strong, between 0.4 and 0.6 as moderate, between 0.2 and 0.4 as weak, and between 0.2 and 0.0 as very weak or negligible. The relationships between the dimensions of principal and teacher behaviour were determined using Spearman's correlation coefficient and are depicted in Table 9.

The correlation coefficients between principal supportive and directive behaviour were interpreted as weak according to Salkind's interpretation (Table 9). Similarly, the correlations coefficients between supportive and directive principal behaviour and teachers engaged and frustrated behaviour were found to signify weak relationships. Furthermore, the relationships between teachers' engaged and frustrated behaviour were interpreted as weak. The weak strengths of these relationships indicate that they did not influence each other in a practical manner, even though they signified relationships between each other, and thus warranted no effect in practice.

Discussion

It is important to reiterate that the scores were interpreted according to the comparison with the New Jersey high school averages as presented by Hoy et al. (1991) and as indicated earlier and based on the extant use of the OCDQ-RS as a reliable measure of school climate. The main findings of this study reveal unexpected perceptions of schools' organisational climates regarding:

• principals' and teachers' behavioural dimensions; and

• the types of their organisational climates.

Firstly, the organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools displayed very high directive and below average supportive principal behaviour, which suggest that principals at these schools were rigid and domineering and intent on maintaining close and constant monitoring of all teachers and school activities to the smallest detail. According to Lazridou and Tsolakidis, (2011), this primarily suggests managerial principals' roles as against provision of leadership. This is more so in light of these schools being well-performing under challenging conditions, which might perpetuate the notion that high directive behaviour is critical for good performance. This implies the need for capacity-building of school leadership not only to target quantifiable outputs such as NSC results, but focus on holistic school organisational behaviour and development.

Secondly, teacher behaviour showed low engagement and above-average frustration. Engaged behaviour means that teachers are proud of the school, enjoy working with one another, are supportive of their colleagues and committed to the success of their learners. Frustrated behaviour is characterised by staff who feel burdened with routine duties, administrative paper work and excessive assignments unrelated to teaching. The ideal situation is where teachers are highly engaged and less frustrated and exhibit high morale, care for learners' welfare, independent work and commitment.

Thirdly, schools' organisational climates were found to be closed and seemed to indicate depressing climates at most, since per definition of organisational climate, high openness was expected from both principal and teacher behaviours at well-performing schools.

The unexpected results prompted an examination of descriptive data to get a sense of teachers' responses to school organisational dimension items. On principal directive behaviour, it was indeed found that the majority of teachers perceived principals as sometimes and often directive. This finding supports principal behaviour which was found to be highly directive.

Items on supportive behaviour surprisingly indicated principals being perceived as supportive.

This is puzzling considering that principal behaviour was overall perceived as below average supportive and highly directive. The possible reason for teachers' perceptions could be that principals provided detailed direction for work performance. This, we regard as directive support. In this regard, Vos et al. (2012:64), in their study of school organisational climates in South Africa conclude "[...], one has to note that the South African educators experienced most of the directive behaviour as positive, and not as negative" and thus, most items on directive behaviour can be viewed as supportive, which can be interpreted as directive support behaviour, which could explain the schools' consistent performance despite their historically disadvantaged circumstances. This finds support in perceptions indicating that it sometimes occurs that principals are autocratic while they complement and help teachers, use constructive criticism and look out for teachers' welfare. This suggests that directive support behaviour is the reason that teachers exhibit features of engaged behaviour.

Items on teacher behaviour mostly indicated frustration as sometimes and rarely occurring. Only items relating to teachers having too many committee requirements, administrative paperwork being burdensome and assigned non-teaching duties being excessive were indicated as often occurring. While understandable and real as asserted by Maddock and Maroun (2018) and Mbatha's (2016) that the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement remains difficult for teachers because of large classes and heavy administrative workloads, we take the view that this cannot be indicative of overall frustrated behaviour per definition of this behaviour. This, could rather be an indication of the connotation ascribed to items of the OCDQ-RS in the South African context.

Engaged teacher behaviour seems to yield mixed results. On the one hand, teachers' perceptions indicated engaged behaviour while indicating disengaged behaviour on the other. Notably, disengaged behaviour seemed to involve learner issues while engaged behaviour seemed to involve matters pertaining mostly to teachers' own issues. This was also puzzling as it could be expected that at these schools, teachers would be fully engaged. It is also noteworthy that the majority of teachers indicated rarely and sometimes experiencing high morale. It is possible that engaged behaviour was very low because of matters including discipline, which is one often reported challenge at schools (Mahamba, 2019; Obadire & Sinthumule, 2021).

The correlations between organisational climate dimensions indicate relationships which are not strong enough to be of predictive inferential value. Rather, they indicate, as a response to one another, weak relationships between dimensions of the OCDQ-RS.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The OCDQ-RS results indicated that well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools showed very high directive and below average supportive principal behaviour. It was also found that teacher behaviour was very low engaged and above average frustrated. Moreover, types of school organisational climates were found to be closed because of low principal and teacher openness behaviour. In practice, these findings imply organisational climate improvement efforts geared towards openness through principals decreasing directive behaviour and increasing supportive behaviour, which will result in increased teacher openness behaviour.

Data on items of the dimensions of the OCDQ-RS raised theoretical implications. The possibility exists that the OCDQ-RS description of organisational climate dimensions and its attendant items may convey different meanings in the South African school context as pointed out in the directive and supportive behaviour dimensions. This implies the necessity for validating the OCDQ-RS for South Africa. The language and terminology used may be the reason for a different understanding of its constructs such as the implications of directive support as opposed to directive-autocratic behaviour. It is, therefore, recommended that the OCDQ-RS is subjected to validation and standardisation for the South African context.

Studies of the nature of organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged schools should be conducted using mixed methods research to derive value from the qualitative exploration of what causes frustrated teacher behaviour, highly directive and below-average supportive principal behaviour from lived experiences of teachers and principals.

As pointed out earlier, no studies on school organisational climates of well-performing, historically disadvantaged secondary schools were identified from which parallels could be drawn and as such, this limited a comparison with existing studies. This study was limited by the low reliability index of intimate teacher behaviour as a dimension. Nevertheless, this study provides important insights on school organisational climates at these schools. It is also noteworthy that the OCDQ-RS only measures the organisational climate and thus how teachers experience their school cultures, and does not proffer reasons for the performance of the schools. Rather, it is suggested that organisational climate and other contextual factors may be responsible for the performance of these schools and implies a need for further studies on why these schools perform well despite their disadvantaged circumstances and most importantly, whether their characterisation as well-performing schools implies that they are effective schools.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge and thank the critical reviewers for constructive comments and suggestion to improve the article.

Authors' Contributions

SKM collected data and facilitated analysis with the statistician of the university - Professor (Prof.) Suria Ellis. SKM and MIX wrote the literature review. MIX conducted the statistical analysis for the article. MIX and SKM interpreted the data. MIX and SKM reviewed the article as guided by the critical readers. MIX wrote the final draft for review and corresponded with the SAJE Administrative and Publishing Editor.

Notes

i. This article is based on a Master's dissertation by Salome Kelly Mofokeng.

ii. The NSC is the basic schooling exit point and is currently the only indicator for school performance outcomes in South Africa.

iii. The OCDQ-RS, together with the guidelines for analysing and interpreting data, was used with the authors' permission in the interest of educational research. In this regard, the authors, Hoy et al. (1991:173) state: We encourage the use of the instruments. Simply reproduce them and use them. Share your results with us so that we can refine the measures and develop comprehensive norms. Many administrators learned to use such instruments when they were in graduate school, but their skills have grown rusty. If we can help you, let us know.

iv. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

v. DATES: Received: 5 August 2019; Revised: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 31 December 2021.

References

Check J & Schutt RK 2012. Research methods in education. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cohen J, Pickeral T & McClostey M 2009. The challenge of assessing school climate: What is school climate? Leadership and Management, 66(4): 1-5. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Delport CSL 2002. Quantitative data collection methods. In AS De Vos (ed). Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2018. The 2018 National Senior Certificate results: Schools performance report. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.ecexams.co.za/2018_Nov_Exam_Results/NSC%202018%20School%20Performance%20Report%20WEB.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2005. Motshekga: Release of 2005 matric exam results. 29 December, Wits College of Education, Johannesburg, South Africa. Available at https://www.polity.org.za/article/motshekga-release-of-2005-matric-exam-results-29122005-2005-12-29. Accessed 4 November 2009. [ Links ]

De Villiers E 2006. Educators' perceptions of school climate in primary schools in the Southern Cape. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/1647/dissertation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Gogtay NJ & Thatte UM 2017. Principles of correlation analysis. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 65:78-81. Available at https://www.kem.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/9-Principles_of_correlation-1.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Holloway JB 2012. Leadership behavior and organizational climate: An empirical study in a non-profit organization. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 5(1):9-35. [ Links ]

Hoy WK & Miskel CG 2005. Educational administration: Theory, research, and practice (7th ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Hoy WK, Tarter CJ & Kottkamp RB 1991. Open schools/healthy schools: Measuring organizational climate. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Available at http://www.waynekhoy.com/pdfs/open_schools_healthy_schools_book.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Janson M & Xaba MI 2013. The organisational culture of the school. In PC Van der Westhuizen (ed). Schools as organisations (4th ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Kane-Berman J 2018. Why some schools succeed - IRR. Available at https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/why-some-schools-succeed--irr. Accessed 20 May 2019. [ Links ]

Lazridou A & Tsolakidis I 2011. An exploration of organizational climate in Greek high schools. Academic Leadership: The Online Journal, 9(1):Art. 8. Available at https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol9/iss1/8. Accessed 17 February 2016. [ Links ]

Maddock L & Maroun W 2018. Exploring the present state of South African education: Challenges and recommendations. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(2):192-214. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-2-1641 [ Links ]

Mahamba C 2019. Can return of corporal punishment bring discipline in schools? Star, 19 April. Available at https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/can-return-of-corporal-punishment-bring-discipline-in-schools-21556881. Accessed 26 August 2019. [ Links ]

Mbatha MG 2016. Teachers' experiences of implementing the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) in Grade 10 in selected schools at Ndwedwe in Durban. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43178032.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Mentz PJ 2013. Organisational climate in schools. In PC Van der Westhuizen (ed). Schools as organisations (4th ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Mofokeng SK 2019. An investigation of the school organisational climates of well-performing previously disadvantaged secondary schools. MEd dissertation. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: NorthWest University. Available at http://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/32251/Mofokeng_SK.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Moolman B, Essop R, Makoae M, Swartz S & Solomon, JP 2020. School climate, an enabling factor in an effective peer education environment: Lessons from schools in South Africa. South African Journal of Education. 40(1):Art. #1458, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1458 [ Links ]

Motsiri TM 2008. The correlation between the principal's leadership styles and the school organisational climate. MEd dissertation. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: North-West University. Available at http://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/1860. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Nkosi B 2020. Matric results: 'Sad story' as schools with zero passes increase. Star, 7 January. Available at https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/matric-results-sad-story-as-schools-with-zero-passes-increase-40216874. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Obadire OT & Sinthumule DA 2021. Learner discipline in the post-corporal punishment era: What an experience! South African Journal of Education. 41(2):Art. #1862, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n2a1862 [ Links ]

Pietersen J & Maree K 2016. Overview of some of the most popular statistical techniques. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Pretorius S & De Villiers E 2009. Educators' perceptions of school climate and health in selected primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 29(1):33-52. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n1a230 [ Links ]

Salkind NJ 2014. Statistics for people who think they hate statistics (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Tavakol M & Dennick R 2011. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2:53-55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [ Links ]

Theron AMC 2013. General characteristics of the school as an organisations. In PC Van der Westhuizen (ed). Schools as organisations (4th ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Tubbs JE & Garner M 2008. The impact of school climate on school outcomes. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 5(9):17-26. Available at https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1615&context=facpubs. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students 2016. Quick guide on making school climate improvements. Washington, DC: Author. Available at https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/NCSSLE_SCIRP_QuickGuide508.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2020. [ Links ]

Vos D, Van der Westhuizen PC, Mentz PJ & Ellis SM 2012. Educators and the quality of their work environment: An analysis of the organisational climate in primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 32(1):56-68. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n1a520 [ Links ]

Ziduli M, Buka AM, Molepo M & Jadezweni MM 2018. Leadership styles of secondary school principals: South African cases. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 22(1-3):1-10. https://doi.org/10.31901/24566322.2019/23.1-3.911 [ Links ]