Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 supl.2 Pretoria Dez. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41ns2a1960

An investigation into policy implementation by primary school principals in the Free State province

S.B. Thajane; M.G. Masitsa

Department of Education, Faculty of Humanities, Central University of Technology, Welkom, South Africa. sbthajane@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Despite numerous attempts by the Free State Department of Education to train primary school principals on how to design and implement school policies, numerous schools do not implement school policies satisfactorily. In this article we examine the implementation of school policies in township primary schools in the Free State province, South Africa. The sample of the study consisted of 60 township primary school principals who were randomly selected from 160 township primary schools across the province. The participants completed a questionnaire based on policy implementation in township primary schools. Prior to completion, the questionnaire was tested for reliability using the Cronbach alpha coefficient. The questionnaire was found to have a reliability score of 0.909, which indicates a high level of internal consistency. The questionnaire was electronically analysed using the SPSS. The results of the analysis reveal that some school policies were reasonably well implemented at schools, while other policies were poorly implemented. This article concludes with recommendations on addressing the problem.

Keywords: implementation problems; policy implementation; school management; school policy; township primary schools

Introduction

In South Africa and throughout the world, the establishment and administration of education systems is the responsibility of the state. South Africa has nine provinces and each of them has a unique set of education circumstances that need to be managed. The country has a national department of education (DoE), namely the Department of Basic Education [DBE], which is headed by the Minister of Education and nine Provincial Departments of Education, each headed by a Member of the Executive Council (MEC).

The National Minister of Education sets national education policy and is responsible for ensuring that education is provided evenly in all nine provinces. The MECs set provincial education policies in those instances where the Minister of Education has not yet determined policies - otherwise they implement national education policy. The MECs also ensure the smooth provision of schooling in their respective provinces.

This article is based on an investigation on policy implementation by primary school principals in the Free State province, one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Policy simply means prudence in the conduct of affairs and refers to a plan of action or a statement of ideals adopted. It provides well thought out guidelines for doing something. It is a binding document on government officials as it effectively constitutes a management instruction to such officials (South Africa, 2008a:65).

Statement of the Problem and Aim of the Research

The Free State Department of Education has experienced problems of policy implementation by township primary school principals for a number of years. The DoE has school policies in place but at the level of implementation, these policies are not properly enforced (DBE, Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2012:2; Free State Department of Education, 2005:38, 2008:27; Mgijima, 2014:204). Poor or a lack of implementation of school policies has led to problems that have hampered the principals' effective management of their schools. If school policies are poorly implemented or are not implemented at all, it implies that the principal's management of the school is not effective.

To illustrate the magnitude of the problems of poor policy implementation in the primary schools, the following example is briefly explained. Safety policy requires that schools form safety committees whose responsibility would be to draft the school safety policy rules. However, in some schools such committees did not exist. The result was that those schools did not apply safety measures in schools adequately and this led to intruders entering school premises unnoticed (DBE, 2011:96; Free State Department of Education, 2008:27, 2009:3; Le Roux, 2002:95).

Theft and vandalism are serious problems experienced by township primary schools in the Free State. As a result of not installing security at centres housing school computers, photocopying machines and other valuable properties of the school, these facilities were robbed or vandalised (Chapman & King, 2008:39; DBE, RSA, 2010:6; Free State Department of Education, 2008:27, 2013:62). This problem had an impact on the management of schools in that principals sometimes had to abandon their school duties to attend court cases due to theft and vandalism that occurred in schools.

The role of the principal as the manager of the school is to ensure that there is daily planning, organising, operating, executing, maintaining and scheduling of numerous processes, activities and tasks that permit a school to accomplish its goals as an organisation (Matthews & Crow, 2010:29). The principal's task is to ensure that all school policies are implemented accurately and continuously. In the light of the foregoing, the aim of this study was to investigate policy implementation problems experienced by township primary school principals in the Free State province. A literature review was undertaken on the issues of policy implementation problems in township primary schools and an empirical investigation was conducted on the basis of the principals' views regarding policy implementation problems at their schools. The study aimed to explore the following research question: What are the policy implementation problems experienced by township primary school principals?

The Phenomenon of a School Policy

A school is an educational institution. There are various types of schools, including pre-schools, primary schools, high schools, trade schools and vocational schools. The research undertaken in this study was based on primary schools, which range from Grade 1 to Grade 7 in South Africa. The concept "policy" refers to a plan of action, especially of an administrative nature, that is designed to achieve a particular aim of the school. The policy contains guidelines and directions on how something should be done. It, therefore, serves as a guide for making management, functional and administrative decisions. It allows the executor of policy to make decisions within a certain framework (Van Deventer & Kruger, 2003:91). The reason for policy formulation is always triggered by something, and policy must comply with state law and constitution.

According to Badenhorst, (1987, in Badenhorst, Calitz, Van Schalkwyk & Van Wyk, 1987:9), any organisation is established with a specific objective in mind. In the case of a school, the overall objective is educative teaching. However, to merely say that this is the school's objective is not enough. Definite steps must be taken to ensure that this objective is realised. The usual starting point in this process is policy making. The purpose for which the undertaking is established is reflected in its policy. For the school to run its academic and non-academic activities successfully, it has to formulate a policy for its activities. A policy describes and stipulates how each activity should be undertaken or performed. Thus, the content and implications of the policy and the action and procedures which will be adopted by teachers to implement the policy must be outlined. The policy must be communicated to all with an interest in it. South African school policies are formulated by the DBE, Provincial Departments of Education, schools and school governing bodies. Some school policies are derived from the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996b, (hereafter referred to the Constitution) or legislation, while others are not.

The gist of this investigation is policy implementation. Policy implementation refers to the way or manner in which a policy is put into effect and how its objectives are realised. Stated differently, it means translating the goals and objectives of a policy into an action. As a rule, policy implementation should enable the accomplishment of what the policy stands for or is about (Joubert & Bray 2007:60). In support, Duemer and Mendez-Morse (2002:1) state that implementation is the means by which policy is carried into effect. It involves the process of moving from decision to operation. In the context of this article, implementation should enable the school to accomplish what it intends to achieve with its different policies. Policy implementation is measured by how effective it is implemented. This implies that the implementation of a policy can be done either correctly by following its implementation guidelines, or incorrectly by not following its implementation guidelines. In order to achieve its aim a policy must be implemented correctly or in accordance with its implementation guidelines. In this study we investigated policy implementation in primary schools. The intention was to establish whether policies were implemented correctly or not, and if possible, to establish reasons for poor implementation. This, in turn, should enable the Free State Department of Education and schools to introduce corrective measures.

Honing (2006:1) contends that education policy has amounted to a search for two types of policies, implementable policies and successful policies. Thus, implementability and success are important policy outcomes. However, recent trends in education policy signal the importance of re-examining what we know about what gets implemented and what works. Consequently, Honing (2006:1-2) claims that "research and experience continue to deepen knowledge about how learners experiences in school are highly dependent on conditions in their neighbourhoods, families and peer groups. In such contentions, interconnected and multidimentional arenas, no one policy gets implemented or is successful everywhere all the time." Thus, implementability and success are dependent on, or influenced by, conditions prevailing in the learners' environment. This suggests that those improving the quality of policy implementation not only focus on what is implementable and what works, but should further investigate under what conditions, if any, policies get implemented and work. The essential implementation question then becomes not simply "what is implementable and works" but what is implementable and works for whom, where, when and why?

Viennet and Pont (2017:18) claim that several crucial factors are linked to the policy that have a profound influence on and determine policy implementation such as policy justification, policy logic, and feasibility. "A policy may be the result of a need or perception which is outlined clearly to lead to the formulation, legitimacy and implementation of a solution. In order to galvanise support, policy justification should present a clear idea of the expected results from the implementation of the policy since this will move supporters forward" (Viennet & Pont 2017:26). Further, for implementation to be successful, policy targets and goals must be clear and concrete. "The causal theory underpinning the policy is essential, because it tells the story of how and why the policy change takes place and can contribute to get engagement and guide those involved" (Viennet & Pont 2017:29). Lastly, policy designers must ensure that the new policy will be easily implementable in the new environment.

Policies are not self-executing. Garn (1999:2) states that "[s]imply because policy makers express the explicit intentions in policy does not guarantee those aims will be preserved through the policy implementation process." He contends that problems such as not convincing policy implementers to adhere to the spirit of the policy makers' mandate and the absence of will and motivation to embrace policy objectives are some of the problems encountered during policy implementation. In support, Viennet and Pont (2017:10) found that the reasons preventing effective policy implementation include a lack of focus on the implementation process when defining policies at the system level, the lack of recognition that the change processes require engaging people at the core and the need to revise implementation frameworks to adapt to new complex governance systems.

Literature review

Policy implementation problems experienced by township primary school principals

The Free State Department of Education experiences poor policy implementation problems in primary schools, which hamper the principals' effective management of the schools. Poor policy implementation in primary schools has been experienced in some of the following policies and has led to the ineffective running of schools.

Admission policy

The aim of the admission policy, among others, is to ensure that school beginners are admitted to school at the right age. According to the admission policy of the DBE, learners should be admitted to school at the age of 5 years, turning 6 by 30 June in the year of admission for Grade 1. However, according to the Free State Department of Education, in some schools there are numerous learners who are admitted before they reach the age of 5 years (Free State Department of Education, 2009:3). Learners who are admitted before they are ready for admission fail at the end of their first school year because they are not yet ready to meet the academic and social challenges of the first school year. Learners who fail have to repeat the same grade in the following year and this leads to overcrowding, shortage of books and desks, and sometimes educators (RSA, 1996a).

The learner admission policy provides for the orientation and induction of new learners but, in some schools, school orientation and induction programmes are not in place. This results in new learners not being oriented and inducted in how to behave, learn and do other things at school. A lack of or poor implementation of the induction and orientation programmes may give rise to things being done or happening in a disorderly manner at the school and in retarding the teaching and learning programmes, which could lead to learners failing at the end of the year. Le Roux (2002:95) confirms this by stating that "the learner admission policy provides orientation to new learners. The new learners who are not oriented and inducted on how to do things at school may not behave or learn well nor meet other school challenges. The principals who do not implement orientation and induction programmes for learners will always be compelled to address problems caused by poor or lack of learner orientation and induction." This takes considerable time from their management programmes.

Language policy

The aim of the language policy is to give guidelines on how a language of instruction should be used in schools. Every child has the right to receive education in the official language of their choice in public schools. This policy is in compliance with section 6(4) of the Constitution that states that "all official languages must enjoy parity of esteem and must be treated equitably" (RSA, 1996b). According to the language policy, all languages should receive equitable time, resource allocation and respect but this is not the case in some schools where two languages are used as media of instruction. The language policy is mainly intended to enable the learner to use a familiar language as a medium of instruction. A sound mastery of language is essential when the child starts school.

The SGB determines the language policy of the school in consultation with various stakeholders. No form of racial discrimination may be practised in implementing language policy (RSA, 1996a:s. 6(3)). All stakeholders should ensure that the language policy meets the needs of the school community were languages other than the school' s language of learning and teaching (LoLT) or language of instruction are spoken. Before learners can use their home language as the language of instruction at school, they should constitute a class of at least 40 learners, but in some cases parents may demand that their language be used as a medium of instruction even if there are fewer than 40 learners (South Africa, 2000:54).

Safety policy

The aim of the safety policy is to ensure that educators and learners are safe at school and that educators maintain discipline of learners inside as well as outside the classroom. According to the DBE, learners should be supervised at all times and should not be disciplined by means of corporal punishment (South Africa, 2008c:256). According to South African Schools Act 84 of 1996 (RSA, 1996a), schools must have a school safety policy in place. The establishment of a school safety policy is in compliance with section 12(1) of the Constitution, which states that "everyone has the right to freedom and security of the person, including the right to be free from all forms of violence from either public or private sources, not to be tortured in any way and not to be treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way" (RSA, 1996b).

A school safety policy requires the schools to form safety committees whose responsibility it is to draft the school safety policy that will be used to manage school safety (RSA, 1996a:s. 30). The school safety committee's primary responsibility is to ensure that the school is a safe place and that everyone at school experiences safety at all times. The school safety committee members formulate, implement and monitor programmes to address school safety. They are supposed to keep the local station Commissioner of the South African Police Services (SAPS) informed on the work of the school safety committee and about the support required by the school from the police station to support their safety measures. The station Commissioner should in turn assist the safety committee members by ensuring that the school safety committee has realistic expectations of the role that the SAPS can play to support the school.

The school' s safety committee ensures that the correct and legal disciplinary measures are implemented to learners who misbehave at school. The safety committee should also ensure that their safety policy stipulates that the school is fenced, that there are no uncovered electric wires at school, that buildings are safe, that entrance into the school premises is controlled, that learners are supervised during breaks, that learners do not come to school with dangerous weapons, and that the school has a sick room with a first aid kit to treat learners who are injured or ill.

The Free State Department of Education has observed that the safety policy in some schools is not implemented as it should be (DoE, 2001:37). For instance, there are no sick rooms for learners who are sick or injured. Schools do not control entrances to their premises. Learners carry dangerous weapons and drugs to school and these offences are not reported to the police. Schools that do not properly implement safety policy experience criminal incidents within the school premises as well as a general lack of safety (South Africa, 2001:37). These incidents have a negative impact, not only on the learners' academic performance and safety, but also on the management of the school. A lack of safety impedes good management. Naicker and Waddy (2003:8) confirm that safety and security have become an increased concern following incidents of robbery, assault and drug dealing on the school premises.

Pregnancy policy

The aim of the pregnancy policy is to make schoolgirls aware that they put their health and future at risk when they become pregnant. Grant and Hallman (2008:369-382) confirm that learner pregnancy is a major problem facing many primary schools in the Free State. The issue of pregnancy among learners is something which the school discourages as it has its own risks and challenges for the school, as discussed below. The pregnancy policy of the DoE states that "any female learner who falls pregnant while attending school should be allowed to proceed with her normal schoolwork until she goes into labour or up until her parents advise the school otherwise" (2001:36). The school should not discourage the attendance of such a learner unless her parents indicated differently.

The well-being of such a learner will be the concern of the school, but the parents should take the responsibility for the learner's health. This policy is in compliance with section 9(3) of the Constitution, which states that "there should be no unfair discrimination directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex and pregnancy (RSA, 1996b). The school will encourage parents to take the learners to the doctor for continuous check-ups or medical examination as the school does not have the expertise on matters related to pregnancy complications." The school will notify the parents about the unusual development of the learner immediately and parents should take the necessary action instantly as the school will not accept or take responsibility for any eventuality. Some principals are reluctant to notify the parents of learners' well-being because this gives them extra work. They feel that it is not their responsibility to notify parents about these learners' well-being during pregnancy. Pregnant learners may sometimes require specialised care, which the school cannot provide (DoE, 2001:37).

Pregnant learners should be allowed to come back to school after labour to continue with their schoolwork. This decision will, however, rest with the family. Every learner who falls pregnant will still be subjected to all school laws and regulations, like all learners at the school. However, in some schools, this policy is not implemented. Learners who become pregnant are advised by their schools to stay at home, and their parents are not consulted. On the other hand, some parents stop their pregnant children from attending school and do not notify the school. The pregnancy policy has been found to have many loopholes because it cannot cover everything concerning child pregnancy.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) policy

The aim of the HIV/AIDS policy is to ensure that all learners are aware of HIV/AIDS and how it can be prevented and that a learner with HIV/AIDS should not be discriminated against at school. This policy is in compliance with section 9(4) of the Constitution, which states that "no person may unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds in terms of subsection (3)" (RSA, 1996b). However, in some schools, this policy is not properly implemented (Beresford, 2001:21). This results in learners being discriminated against because of their HIV status. In some cases, it is difficult for educators and principals to implement the HIV/AIDS policy because they may not know which learners have contracted the disease. In addition, the school is not in a position to provide HIV-positive learners with specialised care. However, it is usually difficult to tell if a person is HIV-positive. There are no typical features that will give one a positive indication that a learner is HIV-positive or has AIDS. It is especially traumatic to a learner when rumours are spread about their HIV status. It is also important to know that every individual has the right not to disclose their HIV status. If this is told in confidence, it is essential that this information is not passed on to fellow staff members or others in the school community.

Learning and teaching support material (LTSM) policy

According to the LTSM policy, each school is supposed to supply learners with LTSM at the beginning of each academic year. The aim of the LTSM policy is to handle or control LTSM according to the regulations of the DBE. According to the DBE, the school should have LTSM in its stock for the purpose of providing each learner with learning materials that will assist them in learning through the academic year (South Africa, 2008b:27). This policy is in compliance with section 38(2) of the South African Schools Act 84 of 1996, which states that "every learner at school must receive books and material for learning at the beginning of the new academic year" (RSA, 1996a).

However, in some schools this policy is not implemented properly (Free State Department of Education, 2008:27). In some instances, learners fail to return books at the end of the year, which results in an acute shortage of books in the following year. A lack of inventory lists and poor LTSM retrieval systems at schools add to the problem. Consequently, new learners or learners who are promoted to the next grade do not receive the LTSM at the beginning of the new academic year. LTSMs provide learners with what they are supposed to learn in a particular grade. These materials also guide learners on how they should learn.

The Free State Department of Education (2008:27) highlights that some schools in the Free State do not submit their stationery and textbook requisitions in time. This delays the process of ordering the LTSM for the following year. As a result of not submitting requisitions in time, learners receive the learning material very late in the new academic year, forcing them to share learning material with other learners. As a result, learners are not being allowed to take books home, but are expected to pass at the end of the year. Learners who do not have LTSM will not learn as much as they should and may consequently fail to progress to the next grade in the following year. It has already been stated that learners who fail increase the problems of overcrowded classes, shortage of learning material and sometimes shortage of educators. This may have a negative impact on the management of the school.

Policy on absenteeism of educators and learners

The aim of the policy on absenteeism of educators and learners is to encourage punctuality and regular school attendance of educators and learners. Educators are aware that regular absenteeism leads to syllabi not being completed in time and, consequently, learners may not perform well at the end of the academic year. At numerous schools in the province absenteeism of educators and learners is still a cause for concern (Spaull, 2013:4). Consequently, educators and learners are not able to complete their syllabi in time. Absenteeism of educators reduces their teaching time and absenteeism of learners reduces their learning time. Both have a negative impact on the learners' academic performance.

The principal is supposed to manage this policy by developing a culture of punctuality and regular attendance at school. It should be a culture that fosters a caring school environment in which the school management team and educators take an interest in each learner' s well-being and are alerted to problems that might affect a learner' s attendance. According to the DBE, RSA (2010:6), educators' absenteeism has many disadvantages that lead to underperformance in general. Irregular absence of educators compromises the smooth administration of the school. Classes without educators cause a lot of noise that disturbs other classes, and compels principals to combine classes or to give educators extra responsibility of attending to classes whose educators are absent. More contingency plans are needed to bridge the gap left by the absent educator; this hampers the management of the school. There will be no value for money if learners are not taught and educators do not teach. When classes are merged, they become overcrowded. Thus, educators' absenteeism has many disadvantages that lead to underperformance in general. It may also have an influence on learner attendance because learners will not be motivated to attend school when their educators do not attend regularly.

Research Design and Methodology

Quantitative Approach

A quantitative empirical investigation was used as a data gathering method in this study. The quantitative approach as a data gathering method is underpinned by a positivistic research paradigm. It follows a numerical method of describing observations or phenomena (Waghid, 2002:42-47). Thus, data used in this study were quantitatively acquired, written down and analysed as indicated in the different tables.

Research Population and Sample

The population for this study included 160 principals of township primary schools. The Free State Department of Education supplied us with a list of all primary schools in the province. From 160 primary schools, 60 schools were randomly selected to form the sample of the study. The sampling method used was simple random sampling. From the list of primary schools, every third school appearing on it was selected until a sample of 60 was reached.

Research Method

We became aware of the problem investigated in this study after undertaking a literature study on school policy problems in township primary schools. Discussions about school policy problems were held with four principals who were not part of the sample and a literature review assisted us in identifying items for inclusion in the questionnaire. The primary aim of the questionnaire was to get quantifiable and comparable data. The use of the questionnaire was suitable as the respondents were scattered over a wide area - the entire Free State province. In the questionnaire, the respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which compliance or non-compliance with school policies occurred at their schools by choosing from five possible answers using a Likert scale in selecting a response. The last part of the questionnaire presented the respondents with the opportunity to indicate the problems experienced by principals when implementing school policies. Data from the questionnaire were electronically analysed by a statistician using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

Validity and Reliability

Cronbach' s alpha coefficient is a measure of internal consistency showing the degree to which all items in a test measure the same attribute (Huysamen, 1993:125). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for the questionnaire and was found to be 0.909, which indicates a high level of internal consistency.

To observe validity and reliability in this study, we set the questions in the questionnaire to be clear and easy to understand. The questionnaire was pre-tested with five principals who did not form part of the sample. Participants were made aware of the significance of providing accurate information and their answers were not discussed. The question instructions were clear and understandable and participants' confidentiality was respected.

Ethical Considerations

The researcher applied to the Free State Department of Education for permission to conduct research in the township primary schools. The principals of the sample schools were informed of their involvement in the study in writing. The participants were informed that the information they provided would be handled with strict confidentiality and that they would not provide their names or those of their schools. Participation in the study was voluntary and information provided would be used only for the purpose of this study. The questionnaire was distributed to the schools and we collected the questionnaires from the schools after the completion thereof.

Administration

Permission was obtained from the Free State Department of Education to conduct research in the primary schools. Later, permission was obtained from the principals to use them in the study. We designed and duplicated the questionnaires and then administered the questionnaires in all the sample schools, and we checked the completed questionnaires for correctness.

Results

In this study we investigated the policy implementation problems experienced by primary school principal in the Free State province. The study yielded the following results.

Profile of Admission Policy

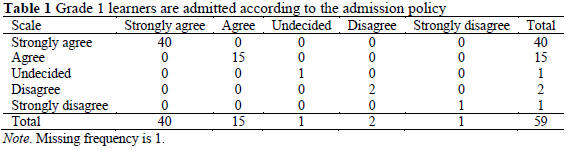

Table 1 above shows that the majority of principals (55) agreed that Grade 1 learners were admitted according to the admission policy of the school. Only three principals disagreed.

An analysis of Table 2 shows that a little more than half of the principals (34) agreed that their admission policy provided for orientation and induction of learners, while 17 principals disagreed.

Profile of Language Policy

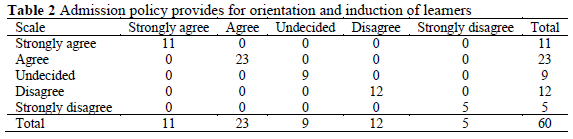

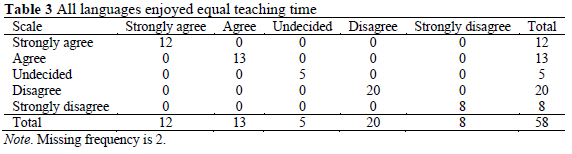

Table 3 reveals that almost half of the principals (28) disagreed that all languages enjoyed equal teaching time while 25 of principals agreed.

Profile of Safety Policy

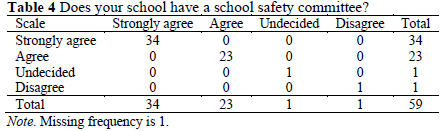

Table 4 shows that the majority of principals (57) agreed that their schools had a safety committee. Only one principal disagreed.

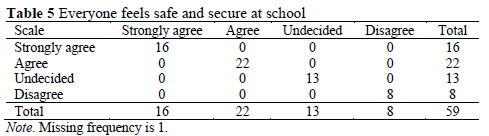

Table 5 indicates that a total of 38 principals agreed that everyone in their schools felt safe and secure, while a noticeable eight principals disagreed and 13 principals were unsure. This is a cause for concern because education must take place in a safe and secure environment.

Profile of HIV/AIDS Policy

Table 6 shows that 33 of the respondents agreed that the pregnancy policy was indeed implemented in their schools, while 12 respondents disagreed.

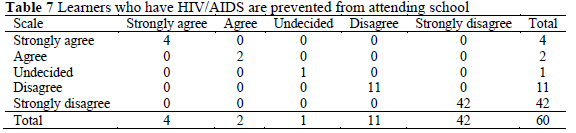

Table 7 shows that 53 of the respondents disagreed that learners with HIV/AIDS were prevented from attending school, while six of the respondents agreed, which is a cause for concern.

Profile of Learning and Teaching Support Material Policy

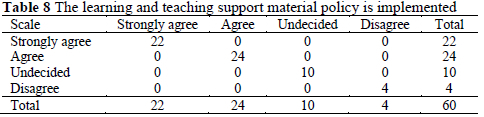

As shown in Table 8, a large number of respondents (46) agreed that the LTSM policy was implemented, while four respondents disagreed and 10 were not sure.

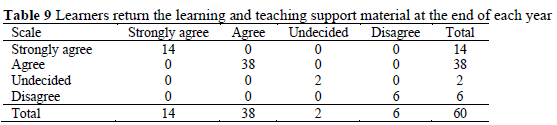

As shown in Table 9, the large majority of the respondents (52) agreed that learners returned the LTSM at the end of each year, while six respondents disagreed.

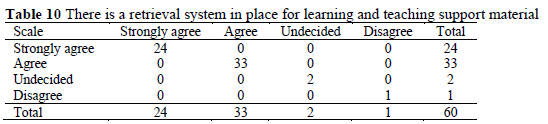

Table 10 shows that the majority of the respondents (57) agreed that there were retrieval systems of LTSM in place. Only one respondent disagreed.

Profile of Absenteeism of Educators and Learners

Table 11 shows that the majority of the respondents (44) agreed that the educators' absenteeism policy was implemented, while 11 respondents disagreed, which is a cause for concern.

Table 12 above shows that 47 of the respondents agreed that the learners' absenteeism policy was implemented and nine respondents disagreed.

The principals who completed the questionnaire indicated that they experienced the following problems when implementing school policies at their schools. Of 60 principals, only 43 indicated that they experienced problems when implementing policies at their schools, and all of them had informed senior officials of the DoE of these problems during their routine school visits.

Some parents register their children late, despite being given registration dates on time. Late registration impacts negatively on both learning and school management. Learners who register late lag behind in their studies because they miss many weeks of learning. In terms of school management, late registrations hamper allocation of teaching resources and facilities such as classrooms, stationery, and allocation of teachers. During registration, some learners do not have birth certificates and other documents such as immunisation cards and certified copies of parents' identity documents (ID), which are required during registration. As a rule, these learners are given 3 months to submit their documents, but some of them would still not submit them 6 months later. Forty three principals experienced these problems. It is, therefore, argued that admission problems experienced in schools are not only due to the principals' non-adherence to admission policy, but can also be attributed to parents who are late with registering their children.

The principals of 25 primary schools agreed that the pregnancy policy was valuable for the school. However, teachers had not been professionally trained to deal with pregnant learners. Furthermore, for cultural reasons, parents seldom report to schools when their children fall pregnant, implying that teachers may not know about the learners' pregnancy until very late. Other parents choose to keep their children at home without notifying the schools. Learners who choose to attend school are not better off because they are often absent from school for a number of reasons. It has also been found that pregnant learners are scared to attend school because they are often mocked by other learners. Therefore, designing a pregnancy policy may not solve all problems faced by pregnant learners, since there are many issues at play which cannot simply be addressed by policy.

The respondents of 10 primary schools claimed that it was easy to design a school policy on HIV/AIDS, but that it was difficult to implement all aspects of it due to the following reasons. Learners who have contracted the disease may not know about their status until very late when their health has deteriorated; learners who have contracted the disease and know their status may not easily divulge the information to their teachers; schools are not equipped with facilities to use in dealing with learners who suffer from the disease; the stigma associated with the disease makes learners who suffer from it either skip classes or drop out of school: and generally, people are afraid to work with those suffering from HIV/AIDS because of the fear of contracting the disease themselves.

It is our considered view that the problems experienced by principals when implementing school policies and their concerns have a negative impact on policy implementation. These problems have a negative impact on the policies' implementability and success (Honing 2006:1).

Discussion

Findings from the literature study suggest that the overriding aim of policy implementation is to achieve implementability and success which, in a school situation, are dependent on the conditions prevailing in the learner' s environment. Policy implementation is influenced by policy justification, policy logic and feasibility. It is dependent on the implementers' attitude about policy as well as on their will and motivation to implement it. Furthermore, being focused on the policy implementation process, involving people at the centre of implementation and flexibility during the implementation process can enhance the implementation process.

The problems experienced by participating principals indicate that they needed clarity about the implementation of certain elements of the pregnancy and HIV/AIDS policies, and have also highlighted that it was not feasible to implement some elements of these policies. Since principals and teachers are not professionally trained to deal with learners who fall pregnant or suffer from HIV/AIDS, learners not knowing their status until very late or not at all, not all elements of the two policies might be implemented fully. As a result, principals need more clarity about the implementation of these policies. Principals also need to discuss the problems that they constantly face when implementing the admissions policy with the DoE.

We found that between 86% and 96% of the sample schools implemented policies regarding governing learner admission, the establishment of school safety committees, allowing learners who have HIV/AIDS to attend school, and retrieval systems for the return of LTSMs at the end of each year. This indicates very good policy implementation by the schools, which can lead to the smooth running of the school. We also found that policies regarding or governing orientation and induction of learners, educators' and learners' absenteeism, and the supply of learning and teaching material were implemented by between 73% and 78% of the sample schools, which indicates good policy implementation.

On the other hand, we also found that policies on learner pregnancy and the allocation of equal teaching time to all languages were implemented by only 43% and 55% of the sample schools, which indicates poor policy implementation. Disregarding departmental guidelines by not allocating equal teaching time for all languages is indicative of poor school management of policy implementation and can hamper effective teaching and learning. The learner pregnancy policy is one of the policies that principals find difficult to implement. Although 96% of the sample schools had safety committees in place, 64% of the participating principals indicated that not everyone at their schools felt safe and secure. This is a serious cause for concern because teaching and learning can only be effective if they occur in a safe and secure environment. Having a safety committee in place cannot guarantee school safety and make teachers and learners feel safe at school, but a safely guarded school can.

In general, we found that the implementation of nine school policies ranged from good to very good and only two school policies were poorly implemented. It is particularly interesting to note that the admission and HIV/AIDS policies were implemented by 93% and 88% of the sampled schools despite a number of problems experienced by the principals in the implementation of these policies. The pregnancy policy was poorly implemented by the sample schools but the implementation of this policy too was fraught with problems and uncertainties.

Recommendations

The following recommendations can go a long way in alleviating the problems experienced by township primary school principals when implementing school policies.

The Free State Department of Education should address problems experienced by the principals when implementing the admission, pregnancy and HIV/AIDS policies, as well as their concerns. Addressing these problems and concerns can eliminate some policy implementation stumbling blocks and thus improve the implementability and success of the policies. The DoE should also assist principals with the implementation of other policies that are poorly implemented at school.

The problem of safety needs to be addressed at provincial and local levels since it has the potential to spill over from one town to another. The provincial security agents, which include the SAPS, should lead the discussion in this regard and suggest solutions on how the problem should be addressed. Since this process can take a long time, schools should ensure that their safety committees are functional and are always in touch with their local police station Commissioners and report to them whatever security problems they encounter.

• It is essential that every new learner receives orientation and induction. Class teachers must be given the responsibility of performing this task because they are the ones who will work closely with the learners most of the time. The principals should ensure that teachers know the school's orientation and induction programme and are able to apply them meticulously.

• The Free State Department of Education should assist principals in drawing up timetables that will ensure that all languages taught at schools are allocated equal teaching time.

• The problem of safety is not only a school problem but a national problem in South Africa. As a result, the problem needs to be addressed at national, provincial and local spheres of government. The national security agents, which include the SAPS, should lead the discussions in this regard and must suggest possible solutions on how the problem should be addressed.

• The problems surrounding pregnant learners are many and are complicated. They revolve on legal, traditional, religious and moral matters, which all too often do not agree on whether or not the pregnant learner should be allowed to attend school. The situation can be aggravated by the fact that pregnant learners are sometimes mocked by their school mates. Thus, a discussion between the pregnant learner's parents, the principal and the school governing body can usually result in an amicable resolution of the problem. Simply sticking to what the law dictates on this matter may not solve the problems that pregnant learners face.

Conclusion

In this study we have investigated policy implementation by primary school principals in the Free State province. We have found that the implementation of nine school policies ranged from good to very good, and only two policies were poorly implemented. This indicates that school policies are satisfactorily implemented in the province although improvements are required for policies that are poorly implemented. We have also revealed problems encountered by principals when implementing the admissions, HIV/AIDS, and pregnancy policies which require intervention and assistance from the DoE. We made a few recommendations which could provide solutions to the policy implementation problem encountered and hopefully address the principals' concerns.

Authors' Contributions

All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. This article is based on the doctoral thesis of Solomon Bereng Thajane.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

iii. DATES: Received: 21 October 2019; Revised: 5 September 2020; Accepted: 5 October 2020; Published: 31 December 2021.

References

Badenhorst DC, Calitz LP, Van Schalkwyk OJ & Van Wyk JG 1987. School management: The task and role of teacher. Pretoria, South Africa: HAUM Educational. [ Links ]

Beresford B 2001. AIDS takes an economic and social toll: Impact on households and economic growth most severe in Southern Africa. Africa Recovery, 15(1-2):19-23. [ Links ]

Chapman C & King R 2008. Differentiated instructional management: Work smarter, not harder. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2010. Report on the National Senior Certificate examination results. Available at https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/reportexamresults20100.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2011. Teacher performance appraisal (TPA) (Post level 1and2). Draft 4.7. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2012. National Senior Certificate examination: National diagnostic report on learner performance. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Diagnstic%20Report%2015%20Jan%202013.pdf?ver=2013-03-12-225718-000. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Report on the school register of needs 2000 survey. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. [ Links ]

Duemer LS & Mendez-Morse 2002. Recovering policy implementation: Understanding implementation through informal communication. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 10(39):1-11. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v10n39.2002 [ Links ]

Free State Department of Education 2005. Managing and leading schools. Bloemfontein, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Free State Department of Education 2008. Education guide on prevention and management of bullying. Bloemfontein, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Free State Department of Education 2009. Educational institution vacancy list one of2009 (Principals posts). Bloemfontein, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Free State Department of Education 2013. School management. Bloemfontein, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Garn GA 1999. Solving policy implementation problem: The case of Arizona charter schools. Education Policy Analyses Archives, 7(26): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v7n26.1999 [ Links ]

Grant MJ & Hallman KK 2008. Pregnancy-related school dropout and prior school performance in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 39(4):369-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00181.x [ Links ]

Honing MI 2006. Complexity and policy investigation: Challenges and opportunity for the field. Albany, NY: University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Huysamen GK 1993. Metodologie vir die sosiale en gedragswetenskappe. Halfweghuis, Suid-Afrika: Southern Boekuitgewers. [ Links ]

Joubert R & Bray E (eds.) 2007. Public school governance in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Interuniversity Centre for Education Law and Education Policy (CELP). [ Links ]

Le Roux AS 2002. Human resources management in education: Theory and practice. Pretoria, South Africa: Ithuthuko Investments. [ Links ]

Matthews LJ & Crow GM 2010. Theprincipalship: New roles in a professional learning community. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Mgijima MN 2014. Violence in South African schools: Perceptions of communities about a persistent problem. Mediterranean Journal of Social Science, 5(14):198-206. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n14p198 [ Links ]

Naicker S & Waddy C 2003. Towards effective school management: Isixaxa mbiji, pulling together, almal saam. Manual 12: Discipline, safety and security. Midrand, South Africa: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996a. Act No. 84, 1996: South African Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 377(17579), November 15. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996b. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of1996). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa 2000. Understanding the South African Schools Act. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2001. Draft revised national curriculum statement. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2008a. Human resources management circular No. 75. Bloemfontein: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2008b. National report on systemic evaluation. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2008c. School management and leadership. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Spaull N 2013. South Africa's education crisis: The quality of education in South Africa 1994-2011. Johannesburg, South Africa: Centre for Development & Enterprise. Available at http://section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Spaull-2013-CDE-report-South-Africas-Education-Crisis.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Van Deventer I & Kruger AG 2003. An educator's guide to school management skills. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Viennet R & Pont B 2017. Education policy implementation: A literature review and proposed framework (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 162). Paris, France: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/fc467a64-en [ Links ]

Waghid Y 2002. Democratic education: Policy and praxis. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]