Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 supl.2 Pretoria Dez. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41ns2a1920

Teachers' perceived self-efficacy in responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment in Lesotho

Mahlape Tseeke

Department of Educational Foundations, Faculty of Education, National University of Lesotho, Maseru, Lesotho. mahlapetseeke@yahoo.co.uk

ABSTRACT

In the study reported on here I explored teachers' perceived self-efficacy in responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools. A descriptive qualitative case study was used as a strategy of inquiry to source data from 6 teachers who taught in inclusive classrooms in mainstream schools. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews and classroom observations. The findings reveal that while extensive experience teaching learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings influenced feelings of high self-efficacy on the participating teachers, low levels of self-efficacy, which were credited to a lack of knowledge, resources, training and support were also greatly experienced. Improving teacher self-efficacy is, therefore, essential and it requires greater investment if successful inclusive education for learners with visual impairment is to be achieved.

Keywords: inclusive education; Lesotho; mainstream; secondary school; self-efficacy; visual impairment

Introduction

Inclusion of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools has not only dramatically transformed the standard of education for these learners, but it has also augmented the responsibilities of teachers. In order to meet the dynamics of inclusive teaching, teachers' roles have shifted from traditional to more innovative roles. Together with having to alter their practices and attitudes to adapt to the changing education system, teachers need to efficiently collaborate with paraprofessionals and other education stakeholders for effective implementation of inclusive education. As Brownell, Adams, Sindelar, Waldron and Vanhofer (2006) affirm, the alliance of teachers and other education stakeholders is vital in accommodating learners with various learning needs in inclusive classrooms. Thus, in order to effect inclusive education for learners with visual impairment, teachers must be part of the team leading the process (Engelbrecht, 2007) and most importantly, they must experience a high sense of self-efficacy, thereby positively influencing learners' success and improving teachers' work satisfaction (Bandura, 2006).

According to Bandura (1997), self-efficacy is the belief that one has about their potential to perform a task in order to produce successful outcome. In other words; teacher self-efficacy is an innate ability on the teacher's part to effectively promote learners' learning. In inclusive settings, teacher self-efficacy is significant because it influences teachers' approaches, their motivation as well as the efforts they invest in delivering instruction for all learners. As such, they can better administer their classes and influence learners' attainment. Although teacher self-efficacy in inclusive settings may vary due to different contexts, some studies agree that it is a crucial factor in terms of realising effective education for learners with visual impairment (Viel-Ruma, Houchins, Jolivette & Benson, 2010). For instance, Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2016) indicate that teachers' self-efficacy in inclusive settings contributes to learners' positive behaviour, motivation and achievement. Teachers whose sense of self-efficacy is high are keen to support and direct learners towards positive accomplishments (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). Thus, they are likely to seek more innovative teaching avenues that could enable them to attend to the needs of learners with barriers to learning. In addition, teachers who comprehend the implications of inclusive education would, therefore, become more accepting about the inclusion of learners with visual impairment. In this study I explore how mainstream secondary school teachers in Lesotho perceived their self-efficacy in responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment, with the hope of identifying factors that enabled and constrained teachers' self-efficacy.

Background

Inclusion of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools in Lesotho can be traced back to 1978 when the Anglican Church of Lesotho enrolled these learners into one of its secondary schools. The government's relatively recent intervention through the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) occurred in the 1990s with a pilot study on inclusive education in eight primary schools and two secondary schools across the country (Mariga & Phachaka, 1993). The success of the study prompted the government's recommendation that inclusive education practices be extended to all schools in Lesotho (Urwick & Elliott, 2010) and this recommendation was made, despite a non-existent inclusive education policy and adequate teacher training on inclusive education, among other things (Johnstone & Chapman, 2009). This, thus, indicated on the part of teachers, limited understanding of what inclusive education in Lesotho entailed.

Two decades on, there is an increase in the number of mainstream secondary schools that enrol learners with visual impairment, despite there still being no inclusive education policy from which clear guidelines can be drawn, to effect successful inclusive education for learners with visual impairment. Although the increase in the number of schools is a significant growth in the overall standard of education for learners with visual impairment in Lesotho since 1978. Teachers who teach in mainstream schools that enrol learners with visual impairment expressed negative attitudes towards inclusion of learners with visual impairment (Tseeke, 2016). This negativity can be a form of behaviour, influenced by feelings of low self-efficacy on teachers' part; which in turn, could jeopardise these learners' chances of receiving quality education. Thus, it reflects concerns about the level of self-efficacy of teachers who teach learners with visual impairment in mainstream schools. According to Malinen, Savolainen and Xu (2012), teacher self-efficacy in mainstream schools is extremely important as it influences change in teachers' attitudes. For instance, teachers who experience low self-efficacy are less inventive; they easily renounce their responsibilities in the face of intricate conditions and in most cases, assume that learners are uneducable (Bandura, 1997). These qualities are attributable to negative attitudes towards inclusion of learners with visual impairment. Thus, it was imperative to explore teachers' perceived self-efficacy in accommodating the needs of learners with visual impairment in mainstream schools, as this can affect learners' behaviour, motivation and achievement.

Inclusive education has received much attention among researchers in Lesotho. However, the research that exists, Eriamiatoe (2013); Johnstone and Chapman (2009); Mosia (2014) and Urwick and Elliott (2010), focuses more on other inclusive education-related matters than it does on teachers in mainstream secondary schools and the potential contribution they could have on successful inclusive education for learners with visual impairment. In addition, there are no studies in Lesotho on teacher self-efficacy in mainstream schools, and very few on inclusion of learners with visual impairment in secondary schools have been conducted (Ralejoe, 2019). Therefore, it is essential to explore teachers' perceived self-efficacy in relation to accommodating the needs of learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings. With this study I intend to fill the gap that exists in Lesotho literature on inclusion of learners with visual impairment in mainstream schools, as knowledge in this area would contribute towards successful implementation of inclusive education. Related studies state that research that seeks to comprehend internal factors, such as teachers' beliefs, is fundamental for efficient implementation of inclusive education for these learners (Podell & Soodak, 1993; You, Kim & Shin, 2019). This is because teacher self-efficacy beliefs among other things determine teachers' attitudes towards inclusive education and how teachers prepare and organise their teaching in order to augment the quality of education for learners experiencing learning difficulties.

This study was informed by my research conducted in 2016, which investigated teachers' perceptions towards inclusion of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools. The findings from the study indicate that teachers' perceptions were influenced by how strong their beliefs were about their capabilities to handle the needs of visually impaired learners. So, based on the results of that study and various other studies (Siegle & McCoach, 2007; Usher & Pajares, 2008) that support the significance of teacher self-efficacy in the practice of inclusive education, it was essential to explore teachers' self-efficacy in mainstream secondary schools in Lesotho in order to generate a knowledge base that shed light on the nature of teachers' self-efficacy, with the hope of identifying factors that enable and constrain teacher self-efficacies. This article was intended to respond to the following research question: What are teachers' perceived self-efficacies in responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools?

Theoretical Framework

Bandura's (1977) social cognitive theory forms the foundation of self-efficacy. The theory posits that people respond to the environmental pressures and intentionally influence their functioning and life occurrences, such as their behaviour, motivation and development in order to influence their desired outcomes (Bandura, 2005:9-10). In other words, by actively engaging in the construction of their environments, people can actually determine the outcome expectancy of their goals. Social cognitive theory further indicates that people's opinions about their competences shape their thoughts, motivation, as well as actions (Benight & Bandura, 2004). For example, people who possess high beliefs in their abilities set themselves exigent targets and work extremely hard to achieve such goals, despite being confronted by failure, and this is because they associate failure with insufficient effort, knowledge and skills (Schunk & Pajares, 2009). Self-efficacy, as embedded in the social cognitive theory, refers to one's convictions about their capability to competently execute a task (Bandura, 1997). This means that people actually perform tasks if they believe that they can execute such tasks and produce positive results (Bandura, 1997). Thus, it plays a significant role in determining how successful one becomes in accomplishing a task. For example, people whose sense of self-efficacy is high, positively deal with intricate tasks with the credence of conquering them; however, people with a low sense of self-efficacy quickly give up when faced with challenging tasks (Bandura, 2006). Additionally, people's beliefs in their capabilities are motivated by four main sources which include mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, affirmation from other people and emotional and physical state in responding to different circumstances (Bandura, 1994). These influences, for instance, can substantially impact how teachers in mainstream schools approach tasks and challenges in order to accommodate the needs of learners with visual impairment. Hence teacher self-efficacy brands itself as a major aspect in the teaching and learning process of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools as this might significantly influence the academic outcomes of such learners.

Teacher self-efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy refers to teachers' confidence about their capability to successfully influence efficient learning for learners with various learning barriers in order to bring about preferred educational outcomes (Bandura, 1997). Due to these beliefs, teachers can overcome barriers to learning and create teaching environments that provide equal access to education by all learners. According to Wood and Olivier (2007), educators who experience a high sense of self-efficacy approach teaching with enthusiasm and dedication, and are seldom absent and consequently achieve higher education outcomes. For example, a study conducted by Chestnut and Cullen (2014) showed a positive connection between teachers' self-efficacy and their progressiveness towards fresh ideas and learners' achievement. Similarly, Cheung (2008) found that learners' beliefs in their abilities and accomplishment were considerably related to teachers' beliefs in their abilities to effectively teach learners. This means that teacher self-efficacy influences learners' achievement positively. In addition, when the teacher exhibits a high sense of self-efficacy, learners believe in themselves, see importance in what they are learning and show substantial interest in school (Cheung, 2008). Teacher self-efficacy has been associated with numerous positive results in education, which include the ability to successfully manage the class (Brooks, 2016), innovative teaching strategies (Chestnut & Cullen, 2014), learner motivation (Mojavezi & Tamiz, 2012), teacher commitment (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2016) good learners' behaviour and outcomes (Zee & Koomen, 2016), and the ability to work with special education needs learners (Love, Findley, Ruble & McGrew, 2020). Teacher self-efficacy has been found to positively contribute to a classroom and school-atmosphere, teaching commitment, and positive learner behaviour (Schunk, 2012). Schunk further indicates that teachers who experience a high sense of self-efficacy express greater commitment to assisting and teaching all learners. You et al. (2019) noted that teachers with high self-efficacy made more efforts to improve their teaching skills and positive classroom management strategies; they also showed more flexibility when accepting and trying out new ideas and teaching methods. Hence, this can in turn help them devise different strategies that are learner centred to efficiently handle an array of challenges that can be presented by learners with special education needs in their classrooms.

In inclusive education settings, numerous studies have outlined teacher self-efficacy as one of the significant factors which affect the efficient implementation of inclusive education. This is because these beliefs do not only influence teachers' perceptions towards inclusion of learners with various learning needs, but they also contribute to teachers' keenness to modify their practices in order to accommodate different learning abilities (Ahsan, Sharma & Deppeler, 2012; Kristiana & Widayanti, 2017; Sokal & Sharma, 2013). Viel-Ruma et al. (2010) indicate that teachers' belief in their abilities enhances their attainment and overall satisfaction in performance; as such they seldom refer learners who face various learning challenges to special schools (Podell & Soodak, 1993). Podell and Soodak (1993)

discovered that teachers who experienced a high sense of self-efficacy thought that the general education setting was appropriate for placing learners who experienced challenges in their learning. High self-efficacy in this context could influence teachers to apply more effort and devise innovative teaching and learning strategies to accommodate learners with various learning needs; which in turn means increased learner attainment and effective implementation of inclusive education for learners with special education needs. Despite an increase in the number of studies on teacher self-efficacy in inclusive education settings, very few studies investigate teachers' self-efficacy in mainstream secondary schools that enrol learners with visual impairment. The focus of this article is therefore to explore perceived teachers' self-efficacy in inclusive settings.

Research Methodology

Research Design

A descriptive qualitative case study was employed in this study. This research design was deemed appropriate because it provided a platform to explore the meanings that teachers attach to their beliefs of self-efficacy within an inclusive setting. According to Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2007), researchers use case studies to examine the data in depth in order to inform decisions about a phenomenon in the real world. In this study, the case study was used to generate rich in-depth information and understanding of teachers' unique experiences and feelings about their self-efficacy in accommodating the needs of learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings (Yin, 2009).

Participants

The school and participants were purposefully selected because of their suitability of providing rich data for the study (Creswell, 2009). All participants worked at a school that enrolled learners with visual impairment. A total of six teachers, all of whom taught learners with visual impairment in their classrooms, volunteered to take part in the study after an invitation was extended to all teachers at the school. These participants had a minimum of 5 years teaching experience; including teaching learners with visual impairment. Of the total, three participants also provided support services and transcribed Braille for learners with visual impairment, thus they were better positioned to generate rich information about their self-efficacy with regard to responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings (Gall, Gall & Borg, 2007). Although there were other secondary schools that enrolled learners with visual impairment, the school selected was by virtue of its long history of enrolling learners with visual impairment. Unlike other schools that enrolled learners with visual impairment, this school was better resourced with teaching and learning materials, human resources and assistive devices. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Methods of Data Collection

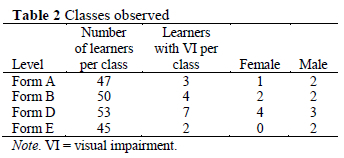

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data because they created a room for participants to express their lived experiences and feelings of self-efficacy in relation to teaching learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings (Kvale, 2007). I used interview schedules that comprised of open-ended questions, which were derived from the research question and objectives. Open-ended questions were used in order to give the participants the liberty to express themselves in relation to their self-efficacy. The interviews lasted for an hour and, with participants' consent, they were audio recorded. The responses were later transcribed verbatim. According to Patton (2002), observation is another method of data collection that can be used in qualitative research, hence observations were also conducted to elicit data to corroborate whether teachers engaged in behaviours of highly efficacious teachers; such as adapting and modifying teaching and assessment strategies, providing and using appropriate teaching materials and assistive devices and modifying the teaching and learning environment to accommodate the needs of learners with visual impairments in their classrooms. Four classes were observed twice for 40 minutes and descriptive field notes, which were later shared with the observed teachers and re-worked for clarity, were taken. Table 2 shows the number of learners with visual impairment per class observed.

Ethical Consideration

Authorisation was obtained from the MOET and the school management to carry out the study at the school. After permission was granted, and the purpose of the study explained to all, teachers at the school were asked to volunteer to take part in the study. Those who agreed to participate were approached and the purpose of the study and a detailed description of research issues were explained. These included the possible risks associated with the study, the research process, the voluntary nature of participation and participants' right to withdraw from the study at any moment that they felt uncomfortable (Creswell, 2009). Matters relating to confidentiality and anonymity were clearly communicated to the participants and, to preserve their identity, participants were asked not to state their names during the interview and this has been maintained - even in print (Hays & Singh, 2012). All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study through verbal and written means.

Data Analysis

Thematic content analysis was used to analyse data. This method picks out, examines and records the occurrence of meanings within data (Anderson, 2007; Braun & Clarke, 2006). The interview recordings, which had been conducted in Sesotho, were transcribed after which they were translated to English. The translation was kept as close as possible to the original version. The field notes taken during the observations were analysed and re-worked for clarity. The observation and interview data were then compared to identify similarities and differences and later collapsed into one data bundle after similar issues were identified. In line with Javadi and Zaria (2016), the data were then coded and categorised into different themes.

Trustworthiness

I conducted a pilot study with two teachers from another school that has enrolled learners who are visually impaired, but whose views are not incorporated in this report. This was done to test whether the interview questions were relevant to the research questions of the study and easy to answer. In addition, member checking was employed to ensure trustworthiness (Baxter & Jack, 2008); data collected through field notes and audio recorded interviews were transcribed and the transcripts were sent to the participants to check for accuracy and clarity (Merriam, 2009).

Limitations of the Study

The study focused on learners with visual impairment and while there are only three schools in Lesotho that enrol learners who are partially and totally blind, the study was limited to only one school. Furthermore, only six teachers were interviewed; of this number, three, apart from teaching, were also employed to transcribe Braille and provide support services for learners with visual impairment. As such no generalisation can be made from this study because the sample size is small. Although the study was envisaged to be completed in 2 months, it took a shorter than expected because the permission letter from the MOET to begin field work was delayed, so I was limited to only a month to carry out the research. However, the data produced was still adequate to answer the research question.

Findings

The following four categories derived from participants' responses to the face-to-face interview questions and classroom observations were revealed by the study: a lack of knowledge and skills, experience, a lack of support and resources and a lack of training.

Lack of Knowledge and Skills

A lack of knowledge and skills has been identified by the participants as one of the factors that disempower them to teach within inclusive settings. Most participants asserted that sufficient knowledge and skills on how to improve their practice would boost their teacher self-efficacy as they would better comprehend how to handle and accommodate visually impaired learners in their teaching. One participant noted: "Teaching in classes that have enrolled learners with visual impairment is about knowing and understanding different ways of imparting knowledge or subject matter to both sighted and visually impaired learners, which we can't say we do at the moment"

Participants further reported feeling frustrated, confused and demotivated to teach in inclusive classrooms as a result of not knowing how to handle the social and academic needs of visually impaired learners. They indicated that they made efforts to adapt their teaching and the teaching environment to attend to the needs of learners with visual impairment; however they were just not convinced that their efforts influenced these learners' performance positively.

Three of the participants indicated being knowledgeable and skilled in transcribing Braille to print and vice-versa. However they asserted that knowledge alone was not sufficient to teach in inclusive classrooms. They expressed their need for more knowledge and skills on how to use various techniques to adapt their instruction to suit the learning abilities of all learners.

Inadequate Teacher Training The participants consented that both pre-service and in-service teacher training were imperative for teaching in inclusive settings as they provided a platform to gain knowledge that enhanced their confidence and strengthened their sense of self-efficacy. They, however, expressed their concern about not receiving either form of training. One participant stated:

None of us, even though we went to school and have teaching qualifications were taught how to teach learners with disabilities; let alone visually impaired learners. And since we have not even received training as teachers in this school, I think that training will help us feel confident and become knowledgeable about inclusive education and hopefully we will even change our attitudes towards these learners because we feel burdened by their presence in our classes.

All the participants asserted that even as employed teachers, they never attended a single professional development training on inclusive education and yet they were expected to teach visually impaired learners. They, therefore, emphasised the need for training in order to acquire knowledge and skills about inclusive education.

Teaching Experience

Some participants admitted to struggling to teach visually impaired learners, hence they experienced low self-efficacy. However, participants with teaching experience of 15 to 23 years indicated that they had learned a few skills on how to handle the needs of these learners. One participant, who had 23 years of experience teaching visually impaired learners in particular, stated that the skills she had developed over the years have enabled her to adapt and modify her classroom and teaching strategies to accommodate visually impaired learners in her classroom. She opines:

It is really difficult to teach these learners because we do not know what works and what doesn't and this is because we know nothing about inclusive education. However, our interactions with them for these many years that we have taught has helped us develop a few skills of how to meet their needs and these skills have been proven to work well because some of these learners perform well in their examinations.

Two of the participants, however, indicated that despite having taught learners with visual impairment for many years, they still felt overwhelmed and demotivated by the magnitude of the challenges they faced teaching these learners and as such indicated experiencing low self-efficacy. One of them said:

I have taught these learners in my class for 8 years; however I always feel like a new teacher whenever I go to class because I am confronted with new challenges every day. I really do not think I have the ability to teach them. Teaching those learners demands new skills every day, skills I really do not have.

Lack of Teaching Resources and Support

Most participants reported feeling less effective due to a lack of resources such as human resources and teaching and learning material. They revealed that a lack of teaching and learning material made them incompetent and less able to assist learners who required additional help:

There is also lack of teaching and learning material, which makes it difficult for us to help these learners even when we really want to. For example, visually impaired learners have no books at all. Books that they have are old and no longer relevant.

Some participants indicated that by failing to hire more teachers and offering professional development training on inclusive education, the MOET was undermining support to learners with visual impairment. Three of these participants explained that despite not being trained to teach learners with visual impairment, the only three teachers that could transcribe Braille into print were burdened with too much work. They were expected to conduct their normal teaching load of 21 to 25 lessons per week, transcribe for both teachers and learners with visual impairment and also handle the academic and social challenges of these learners. This, they asserted, left them with very little time to prepare and devise strategies necessary for effective inclusion, which in turn made them feel less competent leading them to experience low self-efficacy in relation to teaching learners with visual impairment. For example, one teacher revealed:

I think teachers are not enough. Human resource will be enough if the Ministry of Education hires more teachers and every teacher in this school is trained to have skills and knowledge on how to teach these children. The teachers that we have are not enough because they are only knowledgeable in Braille and they are overburdened with work.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore regular teachers' perceived self-efficacy in relation to teaching learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools. The results of this qualitative case study are discussed in this section.

Lack of Knowledge and Skills

While research emphasises the significance of knowledge specific to inclusive education for enhancing teachers' self-assurance to teach in inclusive settings (Ekins, Savolainen & Engelbrecht, 2016; Sharma, Shaukat & Furlonger, 2015; Wang, Tan, Li, Tan & Lim, 2017), the findings in this study reveal that teachers in mainstream secondary schools that enrol learners with visual impairment have insufficient knowledge. This has resulted in participants' sense of low self-efficacy in relation to delivering instruction for learners with visual impairment in inclusive classrooms. The findings confirm Coleman's (2017) study that there is a positive correlation between teacher self-efficacy and the knowledge of providing instruction for learners with special education needs in inclusive settings. Participants felt frustrated, confused and demotivated to, due to inadequate knowledge of inclusive education, teach in classrooms that had learners with visual impairment. In line with Singh and Sakofs' (2006) study, teachers in mainstream secondary schools are not properly equipped to teach in inclusive settings due to insufficient knowledge and skills. In this instance, participants' efforts to make instruction rich and accessible to learners with visual impairment were hampered. According to Bandura (1997), teachers' professional efficacy is encased in their belief that they are capable of teaching and managing learners, and this can lead to stress, frustration and most importantly, negative attitudes towards inclusion of learners with visual impairment. Therefore, I argue that teachers should be equipped with knowledge and skills about inclusive education as this could enable them to devise appropriate instructional strategies for learners with visual impairment, thereby improving their self-efficacy and learners' performance.

Inadequate Teacher Training

With regard to a lack of training in inclusive education, the study revealed that participants were often frustrated and anxious when teaching learners with visual impairment in mainstream classrooms. Participants noted that they encountered problems adapting instruction and modifying the teaching and learning environment for these learners. Inadequate training that would provide skills and knowledge of how to accommodate learners with visual impairment in inclusive classrooms resulted in teachers' sense of low self-efficacy, which manifested in negative attitudes towards inclusion of learners with visual impairment. A lack of training hampers teachers' ability to address the academic and social needs of learners with visual impairment. Al-Adwan and Khatib (2017) assert that insufficient training in inclusive education leaves teachers unsure and unprepared to handle various learning abilities of learners with visual impairment in their classrooms. Similarly, the significance of professional training in inclusive education was established in a study by Leyser, Zeiger and Romi (2011), which shows a positive correlation between in-service teacher training and teacher self-efficacy. Participants in this study noted their need for professional training as this could empower them with ideas and skills of how to effect inclusive education for learners with visual impairment, thereby improving their self-efficacy. Furthermore, as indicated by Gordon (2017), training can instil self-belief in teachers' proficiency to apply various teaching techniques essential in adapting the curriculum to address the needs of learners with visual impairment. Therefore, this points to the provision of professional training that can provide a deeper comprehension of inclusive education, as this can enhance teacher self-efficacy in mainstream schools (Gordon, 2017).

Teaching Experience

The findings of this study reflect contradicting views with regard to the experience which contribute to teachers' sense of self-efficacy. On the one hand, the findings compare with Bandura's (1977) theory that mastery experience influences one's sense of self-efficacy. Participants' sense of self-efficacy is attributed by some participants to many years of teaching learners with visual impairment. Their experiences resulted in developing a few teaching techniques that helped participants cope with the challenges presented by teaching in inclusive settings. In addition, experience teaching learners with visual impairment enabled teachers to regulate and reflect on the degree of their capabilities and effectiveness. Many years of trial and error have empowered teachers with skills to diversify their teaching strategies to accommodate the needs of learners with visual impairment, thereby enhancing teachers' self-efficacy. The findings of this study confirm Williams and Williams' (2010) view that, having conquered one challenge, individuals are likely to feel enthusiastic and capable of taking on the next similar task. On the other hand, the findings show that teaching experience does not always contribute to the teachers' sense of high self-efficacy as indicated in some studies (Obrusnikova, 2008; Subban & Sharma, 2005).

The status of the other teachers, with regard to teaching learners with visual impairment, remained the same as they continued to face challenges despite having taught these learners for a number of years. Therefore, to enhance teachers' self-efficacy, experience should be supplemented by training in inclusive education which is specifically geared towards issues of learners with visual impairment.

Support and Resources

A lack of teaching and learning materials such as Braille and large-print text books and computers not only handicaps the teaching and learning process of learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings but it also contributes to teachers' feelings of doubt and low self-efficacy as evidenced by the findings in this study. Without appropriate teaching and learning materials to support learners with visual impairment, teachers' efforts to accommodate these learners in their classrooms are undermined. Teaching and learning resources facilitate the retention of newly learnt subject matter (Oliva, 2016). Therefore, the absence of these materials threatens the quality of education for learners with visual impairment and teachers' self-assurance in the quality of education they offer to learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings. The study also revealed the MOET's lack of support, which manifested itself in the Ministry's inability to offer in-service training for mainstream teachers and to employ more teachers at the school in order to reduce the workload of the three who also transcribe Braille. A lack of support required to impact teachers' self-efficacy suggests that teachers will continue to experience stress, lack of motivation and less job satisfaction (Bandura, 2006), which will in turn encumber teachers' effectiveness to successfully implement inclusive education for learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings. These learners did not fully access information, especially those with partial sightedness, as no large-print textbooks were available at the school and this further frustrated and affected participants' ability to adapt instruction for these learners, leading to participants' sense of low self-efficacy. The findings confirm Bandura's (1994) idea that one's physiological state can affect one's sense of self-efficacy. Thus, I argue that teachers in mainstream schools that enrol learners with visual impairment cannot experience a sense of high self-efficacy and effect quality teaching for learners with visual impairment if support is not provided. Additionally, reduced teachers' workloads could mean enough time for class preparation, increased motivation and innovative ideas, which in turn, could positively influence teachers' sense of self-efficacy. Therefore, I call for the availability of strengthened support structures and accessibility of teaching and learning material for enhanced teacher self-efficacy.

Conclusion and Recommendations

With this study I set out to explore perceived teacher self-efficacy in responding to the needs of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools in Lesotho. Inclusion of these learners in mainstream secondary schools highlights the role of teachers and the significance of their self-efficacy in effecting successful inclusive education for these learners. Although this article is contextually based, it appears that globally, teachers in mainstream schools struggle to effectively address the needs of learners with special education needs, due to, in part, low self-efficacy (Al-Adwan & Khatib, 2017; Siegle & McCoach, 2007; Usher & Pajares, 2008). From the results in this study we can conclude that teachers in mainstream secondary schools that enrol learners with visual impairment experience a sense of low self-efficacy due to inadequate training, support, resources and a lack of inclusive education knowledge. This study offered an understanding of the significance of equipping teachers in mainstream schools with knowledge necessary to enhance teacher self-efficacy. When teachers believe in their ability to teach learners with visual impairment in inclusive settings, their attitudes towards inclusion become positive and learners' academic achievement is likely to improve. Furthermore, the findings reveal that professional training is an impetus for teachers' high sense of self-efficacy as it could provide them with the necessary knowledge and essential skills for inclusive classrooms, hence on-going professional development in inclusive education should be facilitated. Although experience teaching learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools reflect contradicting views with regard to influencing teacher self-efficacy, it is nevertheless important in effecting inclusive education for learners with visual impairment. As a result, it must be supplemented by increased support from all education stakeholders as this could further enhance teachers' self-efficacy. Additionally, provision of resources cannot be understated because the findings of this study reveal that resources are vital in improving teachers' self-efficacy. Having adequate resources gives teachers the flexibility of varying their teaching methodologies in order to accommodate the needs of learners in inclusive classrooms. Hence, provision of these should take priority for improved teacher self-efficacy and learners' positive academic outcome. Based on the findings of this study, teacher self-efficacy for successful inclusion of learners with visual impairment in mainstream secondary schools is imperative, and as such measures aimed at strengthening such efficacies should take precedence. Therefore, to augment inclusive education for learners with visual impairment, research that investigates measures which MOET has implemented to support teachers in mainstream schools to effectively accommodate learners with special education needs should be conducted, as this would generate valuable insights. A strategic plan devised by ideas collected from teachers in inclusive schools that enrol learners with visual impairment in Lesotho could also be implemented to provide strategies which address the challenges that teachers face. A policy that gives a detailed description on who is responsible for providing support services and how these should be provided for teachers and learners with special education needs, should be developed. In addition, teachers' heavy workloads and struggles to adapt teaching and learning materials to accommodate the needs of learners with visual impairment in their classrooms should influence provision of these resources.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Miss Dineo Tseeke for being the critical reader of this article and the language editor, Dr Mahao Mahao, for making language corrections.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 23 July 2019; Revised: 27 May 2020; Accepted: 22 October 2020; Published: 31 December 2021.

References

Ahsan MT, Sharma U & Deppeler JM 2012. Exploring pre-service teachers' perceived teaching-efficacy, attitudes and concerns about inclusive education in Bangladesh. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 8(2):1-20. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ975715.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2017. [ Links ]

Al-Adwan MAS & Khatib MRF 2017. Competencies needed for the teachers of visually impaired and blind learners in Al Balqaa Province area schools. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 7(4):124-131. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v7n4p124 [ Links ]

Anderson R 2007. Thematic content analysis (TCA): Descriptive presentation of qualitative data. Available at https://rosemarieanderson.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ThematicContentAnalysis.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2019. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1977. Social learning theory. Oxford, England: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1994. Self-efficacy. In VS Ramachaudran (ed). Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. [ Links ]

Bandura A 2005. The evolution of social cognitive theory. In KG Smith & MA Hitt (eds). Great minds in management. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bandura A 2006. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F Pajares & T Urdan (eds). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Baxter P & Jack S 2008. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4):544-559. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573 [ Links ]

Benight CC & Bandura A 2004. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(10):1129-1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008 [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Brooks R 2016. Qualitative teachings in inclusive settings. Voices from the Middle, 23(4):10-13. [ Links ]

Brownell MT, Adams A, Sindelar P, Waldron N & S Vanhofer 2006. Learning from collaboration: The role of teacher qualities. Exceptional Children, 72(2):169-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290607200203 [ Links ]

Chestnut SR & Cullen TA 2014. Effects of self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, and perceptions of future work environment on pre-service teacher commitment. The Teacher Educator, 49(2):116-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2014.887168 [ Links ]

Cheung HY 2008. Teacher efficacy: A comparative study of Hong Kong and Shanghai primary in-service teachers. The Australian Educational Researcher, 35(1):103-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216877 [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2007. Research methods in education (6th ed). London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Coleman M 2017. Enhancing teacher efficacy and pedagogical practices amongst general and special education teachers. PhD dissertation. Glassboro, NJ: Rowan University. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/1887158288?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Ekins A, Savolainen H & Engelbrecht P 2016. An analysis of English teachers' self-efficacy in relation to SEN and disability and its implications in a changing SEN policy context. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(2):236-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1141510 [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P 2007. Creating collaborative partnerships in inclusive schools. In P Engelbrecht & L Green (eds). Responding to the challenges of inclusive education in Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Eriamiatoe P 2013. Realising inclusive education for children with disabilities in Lesotho. Available at https://africlaw.com/2013/07/15/realising-inclusive-education-for-children-with-disabilities-in-lesotho/. Accessed 12 July 2019. [ Links ]

Gall MD, Gall JP & Borg WR 2007. Educational research: An introduction (8th ed). New York, NY: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Gordon TQ 2017. The effects of teacher self-efficacy with the inclusion of students with autism in general education classrooms. PhD dissertation. Chicago, IL: Loyola University Chicago. Available at https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2806. Accessed 24 June 2019. [ Links ]

Hays DG & Singh AA 2012. Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Javadi M & Zaria M 2016. Understanding thematic analysis and its pitfalls. Journal of Client Care, 1(1):34-10. https://doi.org/10.15412/J.JCC.02010107 [ Links ]

Johnstone CJ & Chapman DW 2009. Contributions and constraints to the implementation of inclusive education in Lesotho. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 56(2):131-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120902868582 [ Links ]

Kristiana IF & Widayanti CG 2017. Teachers' attitude and expectation on inclusive education for children with disability: A frontier study in Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. Advance Science Letters, 23(4):3504-3506. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.9149 [ Links ]

Kvale S 2007. Doing interviews. London, England: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208963 [ Links ]

Leyser Y, Zeiger T & Romi S 2011. Changes in self-efficacy of prospective special and general education teachers: Implication for inclusive education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(3):241-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2011.598397 [ Links ]

Love AMA, Findley JA, Ruble LA & McGrew JH 2020. Teacher self-efficacy for teaching students with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with stress, teacher engagement, and student IEP outcomes following COMPASS consultation. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 35(1):47-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357619836767 [ Links ]

Malinen OP, Savolainen H & Xu J 2012. Beijing in-service teachers' self-efficacy and attitudes towards inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4):526-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.12.004 [ Links ]

Mariga L & Phachaka L 1993. Integrating children with special needs into regular primary schools in Lesotho: Report of a feasibility study. Maseru, Lesotho: Ministry of Education. Available at https://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/lesotho_feasibility.pdf. Accessed 28 November 2018. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mojavezi A & Tamiz MP 2012. The impact of teacher self-efficacy on the students' motivation and achievement. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3):483-191. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.3.483-491 [ Links ]

Mosia PA 2014. Threats to inclusive education in Lesotho: An overview of policy and implementation challenges. Africa Education Review, 11(3):292-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2014.934989 [ Links ]

Obrusnikova I 2008. Physical educators' beliefs about teaching children with disabilities. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106(2):637-644. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.106.2.637-644 [ Links ]

Oliva DV 2016. Barreiras e recursos à aprendizagem e á participação de alunos em situação de inclusão [Barriers and resources to learning and participation of inclusive students]. Psicologia USP, 27(3):492-502. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-656420140099 [ Links ]

Patton MQ 2002. Two decades of developments of qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3):261-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636 [ Links ]

Podell DM & Soodak LC 1993. Teacher efficacy and bias in special education referrals. The Journal of Educational Research, 86(4):247-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1993.9941836 [ Links ]

Ralejoe M 2019. Teachers' views on inclusive education for secondary school visually impaired learners: An example from Lesotho. Journal of Education, 76:128-142. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i76a07 [ Links ]

Schunk DH 2012. Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed). London, England: Pearson. Available at http://repository.umpwr.ac.id:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/96/[Dale_H._Schunk]_Learning_Theories_An_EducationaLpdf?sequence=1. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Schunk DH & Pajares F 2009. Self-efficacy theory. In KR Wentzel & A Wigfield (eds). Handbook of motivation at school. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sharma U, Shaukat S & Furlonger B 2015. Attitudes and self-efficacy of pre-service teachers towards inclusion in Pakistan. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 15(2): 97-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12071 [ Links ]

Siegle D & McCoach DB 2007. Increasing student mathematics self-efficacy through teacher training. Journal of Advanced Academics, 18(2):278-312. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2007-353 [ Links ]

Singh D & Sakofs M 2006. General education teachers and students with physical disabilities. Available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/27/fa/4a.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2019. [ Links ]

Skaalvik EM & Skaalvik S 2016. Teacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional, exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Creative Education, 7(13):1785-1799. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.713182 [ Links ]

Sokal L & Sharma U 2013. Canadian in-service teachers' concerns, efficacy, and attitudes about inclusive teaching. Exceptionality Education International, 23(1):59-71. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v23i1.7704 [ Links ]

Subban P & Sharma U 2005. Understanding educator attitudes toward the implementation of inclusive education. Disability Studies Quarterly, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v25i2.545 [ Links ]

Tschannen-Moran M & Woolfolk Hoy A 2001. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7):783-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1 [ Links ]

Tseeke MR 2016. Teachers' perceptions towards the inclusion of learners with visual impairment in inclusive secondary school. MEd dissertation. Wuhan, China: Central China Normal University. [ Links ]

Urwick J & Elliott J 2010. International orthodoxy versus national realities: Inclusive schooling and the education of children with disabilities in Lesotho. Comparative Education, 46(2):137-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050061003775421 [ Links ]

Usher EL & Pajares F 2008. Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4):751-796. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308321456 [ Links ]

Viel-Ruma K, Houchins D, Jolivette K & Benson G 2010. Efficacy beliefs of special educators: The relationships among collective efficacy, teacher self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 33(3):225-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406409360129 [ Links ]

Wang LY, Tan LS, Li JY, Tan I & Lim XF 2017. A qualitative inquiry on sources of teacher efficacy in teaching low-achieving students. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(2): 140-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1052953 [ Links ]

Williams T & Williams K 2010. Self-efficacy and performance in mathematics: Reciprocal determinism in 33 nations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2):453-466. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017271 [ Links ]

Wood L & Olivier T 2007. Increasing the self-efficacy beliefs of life orientation teachers: An evaluation. Education as Change, 11(1):161 - 179. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823200709487158 [ Links ]

Yin R 2009. Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

You S, Kim EK & Shin K 2019. Teachers' belief and efficacy toward inclusive education in early childhood settings in Korea. Sustainability, 11(5):1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051489 [ Links ]

Zee M & Koomen HMY 2016. Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4):981 -1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801 [ Links ]