Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41ns2a2106

Born-free1 learner identities: Changing teacher beliefs to initiate appropriate educational change

Saloshna Vandeyar

Department of Humanities Education, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. saloshna.vandeyar@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

An earlier paper focused on how born-free learners constitute, negotiate and represent their identities after almost two and half decades of democracy in South Africa. Utilising the theoretical framework of subjective realities of educational change, in this article I set out to explore what implications teachers' beliefs hold for born-free learners, and how teachers' beliefs can be changed or adapted to initiate appropriate educational change. The focus of this article is on the beliefs of teachers and how the change thereof can contribute to educational change, based on how learners perceive their identities. The epistemological lens of social constructivism and the research strategy of narrative inquiry was used. Fifty-eight born-free learners across 6 research sites participated in this study. Semi-structured interviews and field notes comprised the data capture, which were analysed using the qualitative content analysis method. Findings reveal that shifting and diverse self-identifications of born-free learners hold fundamental and crucial implications that reside at the heart of educational change, namely a change in teachers' beliefs and in teachers' practice.

Keywords: born-free learners; educational change; identity; subjective realities; teachers' beliefs; teachers' practice

Introduction and Background Context

The coining of the term "born-free" coincided with the dawn of democracy in South Africa. The strong belief that the democratic dispensation would result in a better future for all South Africans seemed to underplay the role of historical, political, social, geographical, and genealogical legacies in constituting, negotiating, and representing identities. Caught up in the jubilation of freedom, many South Africans believed that children born in the democratic era live in "a 'Rainbow Nation' where 'born-frees' run wild and free, possess the inherent ability and are obligated to change society for the better" (Cawe, 2014:1).

More than two decades later, the mask of freedom has unveiled itself to reveal both overt and covert racist practices that serve as an illustration of "fictional freedom." The 2015-2016 protest actions at South African universities were an expression of dissatisfaction of this perceived freedom by born-free learners. For more than two decades, the status quo in the educational arena, namely the curriculum, institutional culture, language policies, permanent appointment into senior promotional posts, has remained relatively the same, with the exception of a change in learner demographics (Matentjie, 2019; Taylor, 2019). It is only as recent as 2018 that language policies at schools and tertiary institutions were challenged and subsequently changed (Mutasa, 2015). The call for decolonisation of educational structures and decolonisation of the curriculum by university students awakened a response from schools and served as a catalyst to begin thinking about decolonising the school curriculum (Fataar, 2018). However, for successful and sustainable educational change to occur, change efforts need to address the key element, namely the teacher.

Teachers are no exception in terms of imposing a born-free identity on their learners. They too hold subjective perceptions and beliefs about the born-free generation of learners. Bradfield (2013:para. 21) argues that the imposition of born-free identities on learners has witnessed the classroom context become "deracialised, degendered and declassed and replaced by an individualised, economised, depoliticised discourse" that takes the focus away from the possibility of social transformation. Teachers would need to change their beliefs according to who the born-free generation of learners are. These learners do not fit in the current education system because they do not self-identify as born-free and the associated properties of that identification. The born-free generation is an identity that has been foisted on them (Cawe, 2014). Thus, there is a mismatch between teacher beliefs and the self-identification of this generation of learners. Beliefs and personal missions of teachers are crucial for educational reform as these directly inform teacher practice (Goodson, 2014). Accordingly, we ask what implications teachers' beliefs hold for born-free learners and how teachers' beliefs can be changed or adapted to initiate appropriate educational change in South Africa?

Exploring the Terrain

Understanding educational change

According to Burner (2018:122), any attempt at understanding educational change needs to respond to three questions: "What is educational change? Why is educational change necessary? How can educational change be made more effective to strengthen its implementation and sustainability?" Educational change possesses some distinctive characteristics, namely it is complex and contextual (Biesta, 2010); it is a multifaceted process that is often difficult to achieve (Fullan, 2009; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012); it is often an expression of political symbolism (Jansen, 2002); it targets school improvement in one way or another (Burner, 2018); it involves various stakeholders (Fullan, 2007); it moves through distinctive stages, namely initiation, implementation, and institutionalisation (Fullan, 2009); and it is a process that deals with what changes need to be made and how to implement these changes (Fullan, 2007).

The necessity for educational change is based on changing contexts such as "increased globalisation, advancements in technology, and developments in research into teaching and learning approaches" (Biesta, 2010:3). Increased globalisation has created populations that are more culturally and linguistically diverse (Czaika & De Haas, 2014). This rich diversity finds its way into the globalised classroom, and deserves attention. Technology has not only introduced new knowledge, but also new ways of learning and operating. Given the pace of advancements in technology, careers of learners and the job market of the future are still in the making. Thus, educational change requires that learners possess unique talents, skills, knowledge and creativity to become empowered to adapt to change (Zhao, 2011). Educational change is also propelled by new knowledge that has been generated about effective teaching and learning approaches (Burner, 2018). Hence, educational change is necessary to keep abreast with the changing times and changing contexts and to best prepare learners for the future.

Fullan (2000:24) claims that to make educational change more effective and to strengthen implementation and sustainability, we need to address aspects of capacity for change. These aspects are twofold, namely, "what individuals can do to develop their effectiveness as change agents, despite the educational system in which people are embedded, and how systems need to be transformed." System and school improvements are mainly driven by teacher agency and professional influence (Campbell, Lieberman, Yashkina, Alexander & Rodway, 2018). When teachers are the drivers of and co-constructors of educational reform, then educational change can be experienced as positive and empowering (Donaldson, 2015). The way that teachers appropriate educational change policy is largely dependent on their beliefs, values, attitudes, and mind-set, all of which inform their practice and experiences of change. According to Fullan (2001:38), educational change comprises three dimensions: the introduction of "new or revised materials, such as curriculum materials or technologies; new teaching approaches", that is, teaching strategies or activities and a change in people's beliefs, such as understandings about the curriculum and learning practices. Real change can only happen if all three dimensions of educational change have been achieved (Fullan, 2009).

The foundation for sustainable reform rests in changing beliefs and understandings as this not only relates to the subjective sides of change (Fullan, 2007) but also to skills and materials which inform and influence practice (McLaughlin & Mitra, 2001). Subjective realities are situated in personal and institutional contexts and histories, all of which need to be negotiated with change efforts (Fullan, 2001). The meaningfulness and effectiveness of new change efforts is dependent on how these subjective realities are addressed or ignored (Vandeyar, 2017). "The way in which teachers contribute to the change and actively participate in 'leading the change' has been shown to be central to the success of any reform effort" (Harris & Jones, 2019:123). Emphasis should be on "the quality of educational change, rather than on change for the sake of change" (Biesta, 2010:157).

Understanding teacher beliefs

So, what are beliefs and how do teacher beliefs inform and influence teacher practice? Definitions of the concepts "belief" and "teachers' beliefs" find its roots in tributaries of psychological and pedagogical trends (Khader, 2012; Pajares, 1992). The concept of beliefs seems to have varied emphasis and varied characteristics, namely it is "knowledge that is subjective and experience-based" (Pehkonen & Pietilä, 2003:2); it is a conceptual portrayal "that signal[s] a reality, truth, or trustworthiness to its holder to ensure reliance upon it as a guide to personal thought and action" (Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000:388); it entails "understandings about the world that are thought to be true" (Philipp, 2007:259); it guides thought and behaviour (Borg, 2001); it is "a set of ideas rooted in the psychological and mental content of the teacher that play a central role in guiding teaching behavior" (Khader, 2012:74) and it is "lenses that affect one's view of some aspect of the world or as dispositions toward action" (Philipp, 2007:259). Khan, Mehmood and Jumani (2018:113) captures these various threads and aptly sums it up by stating that teacher beliefs are viewed "as a filter, interpretive device and transformer of curricular intentions developed elsewhere."

There are two types of teacher beliefs, namely core and peripheral beliefs (Abdi & Asadi, 2015; Pajares, 1992; Phipps & Borg, 2009). Core beliefs are constant, powerfully impact behaviour (Pajares, 1992; Tang, Lee & Chun, 2012), and play a central role in teacher development (Zheng, 2009) influencing unidirectional teaching practices. Peripheral beliefs are less stable and bidirectionally relate with teaching practices.

Beliefs are also divided into categories. Fives and Buehl (2012:473) identify six categories of teacher beliefs: "(a) beliefs about self (teachers' sense of efficacy, identity, and role as a teacher); (b) beliefs about context or environment (school climate/culture, relationships with colleagues, parents and administration); (c) beliefs about content/knowledge of teaching and learning by themselves (mathematics, science, literacy, or social studies); (d) beliefs about specific teaching practices (cooperative learning, teaching science, inquiry approach and strategies); (e) beliefs about teaching approach (constructivism, transmission, or developmentally appropriate practices), and (f) beliefs about learners (diversity, exceptionalities, language differences, ability, learning, and development etc.)."

How do teacher beliefs influence teacher practice? Teacher beliefs are shaped by their own experiences as learners (Xu, 2012) and act as a scaffold, framework, or filter that guides their actions, interpretation of new information, and the goals they set for themselves and for others (Fives & Buehl, 2008). Teacher beliefs deeply influence their instructional practices, teaching decisions, behaviour, and interactions with learners (Abdi & Asadi, 2015; Fives & Buehl, 2012) and may influence learner performance (Biesta, Priestley & Robinson, 2015). What teachers do correlates with their beliefs (Amiryousefi, 2015; Nation & Macalister, 2010). "Beliefs drive classroom actions and influence the teacher change process" (Richardson, 1996:102). Macnab and Payne (2003:55) claim that "the beliefs of teachers -cultural, ideological and personal - are significant determinants of the way they view their role as educators", the way different aspects of the curriculum are emphasised and the choices that are made about teaching. Beliefs inform teacher planning, curricular decisions, choice of learning materials and strongly predict their decisions and classroom practices.

Changing teachers' beliefs is possible (Blömeke, Buchholtz, Suhl & Kaiser, 2014; Fox & Maggioni, 2014). A change in teachers' beliefs can occur by increasing teachers' pedagogical content knowledge (Fives & Gill, 2015). In so doing, teachers may develop more constructivist learning and teaching beliefs. Hence, increasing attention needs to be devoted to the interplay between teacher knowledge and teacher beliefs (Braten & Ferguson, 2015).

Theoretical Moorings: Subjective Realities of Educational Change

Subjective reality is what a person perceives as reality (Hendriks, Van den Putte & De Bruijn, 2015). Subjective reality is susceptible to a set of filters, which may modify a person's perception of that reality (Serov, 2013). Resultantly, personal perceptions of reality may differ between individuals, because of their unique perspectives on our world. The only thing to which one can hold oneself is something one has experienced or perceived. In relation to educational change, subjective realities can be understood in terms of the personal domain of educational change and identity. "The key lacuna in externally mandated change is the link to teachers' professional beliefs and to teachers' own personal missions" (Goodson, 2014:776). Subjective realities are thus a product of identity, which is complex and multifaceted in nature.

Identity formation is focussed on becoming, rather than being and is fluid, context-based and an ongoing process of construction, negotiation, and transformation (Hall, 1996). It involves "a commitment to a sexual orientation, an ideological stance, and a vocational direction" (Marcia, 1980:110). Erikson (1968:22) regards identity as "a process that is located in the core of an individual and also in the core of his communal culture." Culture, history and power all influence how a person identifies. Similarly, Hall (1994:225) emphasises the role of the past in identity formation by claiming that identity formation depends on "how one is positioned by and positions oneself with respect to the past." Thus, the notion of what identity to see "people who look the same", "feel the same thing" or "call themselves by the same name", does not make the same sense anymore (Vandeyar, 2019:459). Because "identity is always viewed from the perspective of the other" (Hall, 1993:49).

Research Strategy

The meta-theoretical framework of this study was social constructivism. At the heart of social constructivism is the social context, wherein meaning-making is generated and attention given to knowing that arises out of shared social and cultural spaces, and not only from within the individual (Schreiber & Valle, 2013). Thus, individual cognitive development is mediated through the social world. According to social constructivism knowledge is a human construction and learners actively engage in educational experiences that enable them to construct their own meaning (Vygotsky, 1978). Dyads and small groups play a key role in social constructivism (Johnson & Horne, 2016). Learner learning occurs through interactions with other learners, their teachers, and parents by means of interpersonal interactions and discussions. The social context of learning is critical as ideas are tested not just on the teacher, but with fellow learners, friends and colleagues (Burr, 2003), highlighting the fact that bidirectional, even multi-directional relationships are needed to describe beliefs and actions in context. Furthermore, institutions such as schools are socially constructed and also play a role in knowledge acquisition. Hence, what is regarded as valued knowledge is also socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1978).

Qualitative inquiry provided the methodological framework of this study. The research design comprised of a bounded case study and narrative inquiry. The case of this study was how born-free learners constitute and negotiate their identities and what implications these identities hold for educational change. Narrative inquiry is a method used to collect, analyse, and represent participants' stories (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). Reality and knowledge are viewed as socially constructed, and "situated within contexts and embedded within historical and cultural stories, beliefs and practices" (Etherington, 2007:599). Furthermore, the reconstruction of a person's experience happens in relation to the other and to a social environment (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). It "is a gentle relational methodology that has the capability to uncover what is important to the person in their situation" (Haydon, Brown & Van der Riet, 2018:125).

The research sites comprised six secondary schools situated in the Gauteng province of South Africa, namely two former White Model C schools [English-medium and Afrikaans-medium], a former Coloured school, a former township school [African],ii a former Indian school and an inner-city school that catered to a majority of black African learners. Secondary schools were chosen because the focus of the study was on adolescents and the self-creation of identity. It is during this phase that the cognitive abilities of adolescents mature and they experience changing societal expectations. The adolescent phase is also characterised by a process of reflection and observation (Brizio, Gabbatore, Tirassa & Bosco, 2015).

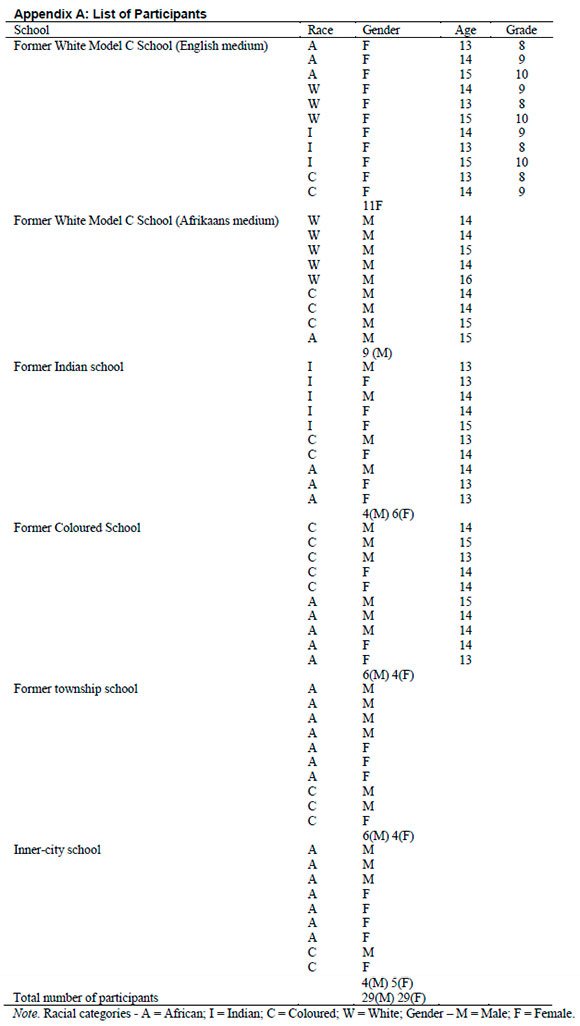

Participants of this study were selected on the basis of race, gender, and national origin (having been born in democratic South Africa). Approximately 10 born-free learners across Grades 8 to 10 at each of the identified schools were selected. An attempt was made to have an equal representation of both male and female learners in the sample at each school. Non-national learners were not included in this study (see Appendix A).

A mix of semi-structured interviews and field notes comprised the data capture of this study. A purposive sample of 58 born-free learners participated in semi-structured interviews. These interviews were conducted in 2015 to 2016 over a period of 6 months. Questions comprised of five to six broad categories and were open ended. The duration of interviews ranged between 45 and 60 minutes. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Pseudonyms were given to the research sites and participants to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

Informal observations of the ethos, culture and practices of the school were recorded as field notes. I was interested in exploring the extent to which born-free learners felt a sense of belonging and being at home at the school. Particular emphasis was on the experiences of born-free learners and how they tried to negotiate a balance between their own and other cultures by establishing relationships with other cultures and simultaneously maintaining what they perceived to be their own ethnic identity and cultural characteristics.

Data were analysed using the qualitative content analysis method. The subjective interpretation of the data underwent the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005:1278). Codes generated from the data were continuously modified "to accommodate new data and new insights about those data" (Sandelowski, 2000:338). Extensive codes and themes arose from this reflexive and interactive process. Codes and themes were organised into higher levels of categories within and across the interviews, observations, and field notes through multiple readings of the data (Merriam, 1998).

Research trustworthiness was achieved by applying the principles of transferability, credibility, dependability, confirmability and authenticity (Butler-Kisber, 2010; Seale, 2000).

The Ethics Committee at the university granted approval to conduct this study.

Findings'''

How Do Born-Free Learners Identify?

Findings on how born-free learners identify were reported in an earlier article (Vandeyar, 2019:456475). I now use those findings and link them to teachers' perceptions with regard to educational change. The focus of this article is on the beliefs of teachers and how the change thereof can contribute to educational change, based on how learners perceive their identities.

Findings revealed that born-free learners did not identify as a collective homogenous group, nor did they accept the imposed identity of born-free. Many competing views of identity that were informed by many other variables other than having been born in democratic South Africa, surfaced. These identities were complex, multifaceted, and numerous in nature.

Born-free learners' identities seemed to be shaped by the politics of identity, and defined by geographical contours of apartheid. These identities were informed by born-free learners' views of democracy in comparison to apartheid and the influence of the enduring memory that they acquired through knowledge in the blood (Jansen, 2009).

A Coloured girl - born as a Coloured girl, live within my region and that is who I am (Gizelle). Secondly, their identities seemed to be shaped by the historical legacy of apartheid. Mindsets of race superiority and rights of many people in South Africa have remained unchanged. Thus, it is not surprising that two and a half decades into democracy, these learners still identify in terms of the legacy of apartheid.

A young Indian woman who is still hampered by the reigns of apartheid and acts of racism -because it is who I see myself as. I am still hampered by another society's opinions and labels (Loshni).

Thirdly, these learners seemed to be trapped between the hyphen, in the form of psychological bondage. The inner psychological struggle of bornfree learners in terms of self-identification emerged in some responses. These learners were caught between allegiance to culture or to the nation. They thus adopted a hyphenated identity, fusing geographical location with cultural origins. For example, "South African Indian"; "South African Coloured"; "South African Muslim" and "White South African."

Fourthly, in contrast, the majority of Black learners identified in terms of personality traits, characteristics and gender. This played out differently in terms of the social context of the school. In mainly monoracial schools, Black learners identified overwhelmingly in terms of personality traits, characteristics and by name, for example, "My name is Zama. I have dark brown eyes and I am dark-skinned and soft-spoken." They did not identify in terms of race, which was a salient feature that their Black counterparts at multiracial schools foregrounded. For example, "Black African female"; "Black male." Some learners at the multiracial schools identified only in terms of gender, "a young woman in South Africa" and "a South African, feminist." Hyphenated identities in terms of geographical location did not feature at all in the self-identification of these group of learners.

In the fifth place, ancestry seemed to play a vital role in the way some learners chose to identify. For example

I am an Indian. I say this because of my ancestors and because that's what I've been told by my parents. I also follow all Indian traditions and customs. My name is also Indian in origin (Shanthi).

I am a Coloured, mixed race - I've been identified as a mixed race child because of how my background of my family is and I would say that I am because it has been passed down through our family, generation after generation. (Cecil)

In the sixth place, some learners challenged societal stereotypical labels with self-imposed identities. "I identify as an individual who occupies space" (Jonathan). Another learner emphasised capabilities and interests, "my identity should not be limited to my race and gender but to my capabilities and interests."

And lastly, only two of the 58 learners identified as born-free.

I identify as a born-free. Free to be who I want to be, free to do what I want (Rabada).

I identify as a person who is born-free in South Africa (Moosa).

Discussion: What Implications Do These Shifting Constructions of Identities Hold for Educational Change?

How do the complex, multifaceted and varied self-identifications of born-free learners affect teachers who are tasked with delivery of the curriculum? What implications do the self-identifications of born-free learners hold for educational change? Clearly a one-size-fits-all approach will not work. It would seem that the self-identifications of born-free learners hold two main implications for effective and sustainable educational change, namely a change in teacher beliefs and a concomitant change in teacher practice.

The sustainability of educational change is largely dependent on the personal and professional commitment of the teacher. Thus, the focus of educational change efforts should address beliefs, personal missions and purposes that inform teachers' commitment to change processes (Goodson, 2014). Beliefs serve as conceptual portrayals or propositions about the world (Peacock, 2001; Philipp, 2007), which "signal a reality, truth, or trustworthiness to its holder to ensure reliance upon it as a guide to personal thought and action" (Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000:388). Thus, if teachers believe that learners hold born-free identities, this will guide their thinking, which will filter into their practice and may be used as an interpretive device and transformer of curricular intentions (Bryan, 2012). Teachers' beliefs also strongly predict their decisions and classroom practices. The homogenous collective identification of learners as born-frees may lead to teachers adopting a "neutral stance" that may subvert the richness of culture in diverse classrooms. A balance needs to be struck between internally and externally mandated change, and personal perspectives of change for effective and sustainable educational reform. A lack of such a balance may result in change forces that are neither humanised nor mobilised. Instead, "change will unfold as political symbolism, lacking personal or internal commitment or ownership" (Vandeyar, 2017:379).

The success of educational change depends on "the way in which teachers contribute to the change and actively participate in leading the change" (Harris & Jones, 2019:123). The most crucial and central components for improved learner outcomes is teacher agency and professional influence (Datnow & Park, 2018; Hargreaves & Ainscow, 2015) and for school and system improvement (Campbell et al., 2018). Real, deep, empowering and sustainable educational change is primarily and profoundly dependant on teachers' identity, culture, value systems, beliefs and lived experiences all of which constitute "knowledge in their blood" (Jansen, 2009) and inform their practice within particular contexts (Vandeyar, 2020). Changing teacher beliefs will lead to fundamental changes in conception, dispositions toward action and behavioural change. When teachers take ownership of the reform and see it as part of their personal and professional mission, then change will be most successful (Goodson & Hargreaves, 1996). As Sheehy (1981) has argued, it is the inner change in teachers' beliefs that promotes educational reform efforts. Thus, teacher beliefs are an important nexus of any educational change. This unidirectional relationship between teacher beliefs and practice is pivotal to the success of any change efforts. However, within this educational social space bidirectional, even multidirectional relationships are required to describe and understand beliefs and actions in context. Beliefs are tested not just on the teacher, but with fellow learners, friends and colleagues, and may have a spiralling effect.

How Can Teacher Beliefs be Changed?

The process of change begins with a transformation of teachers' perceptions by means of a multidirectional focus of the lenses through which they view the world and project outwards into the institutional and social domain. Teachers need to dismantle their polarised thinking and begin to question their ingrained belief systems. Teachers should be willing to navigate their way through cultural borders by re-negotiating their beliefs and ideas to understand and incorporate the values and belief systems of diverse learners. An understanding of their own belief systems as well as the value systems of their learners is required to successfully respond to diversity in their classrooms, and to create educational spaces where all could feel a sense of belonging and feeling at home (Vandeyar, 2017:385). This can be done by increasing teachers' pedagogical content knowledge, which exposes them to experiences of pedagogic dissonance and an ethic of discomfort (Vandeyar, 2020:777). A "conversion" or "gestalt shift" (Nespor, 1987:321) needs to occur so that teachers' beliefs cohere with their practice. Teachers' beliefs are pivotal for understanding and improving educational processes. The focus should be on how teachers change internally and then how this personal change spirals outwards to influence institutional change and societal change (Goodson, 2014; Sheehy, 1981).

How Do Teacher Beliefs Influence Teacher Practice?

Beliefs "drive classroom actions and influence the teacher change process" (Richardson, 1996:102). Cultural, ideological and personal beliefs of teachers inform and influence teachers' purpose of teaching, the way they think about their subject matter, the choices that they make in teaching (Macnab & Payne, 2003) and their behaviours and interactions with learners (Abdi & Asadi, 2015). Teachers should not only examine their beliefs but also explore the effectiveness of their practices in teaching a class of diverse learners (Banks, 2015). I argue that teachers can change their practice by implementing a "pedagogy of compassion" (Vandeyar, 2021; Vandeyar & Swart, 2016, 2019) to ensure effective and sustainable educational change. A pedagogy of compassion comprises the following tenets, namely, dismantling polarised thinking and questioning one's ingrained belief system; changing mindsets; compassionately engaging with diversity in educational spaces; and instilling hope and sustainable peace (Vandeyar & Swart, 2019:776-778).

Dismantling polarised thinking and questioning one's ingrained belief system

Dismantling polarised thinking can only occur through the disruption of received knowledge (Jansen, 2009). A multiplicity of voices should characterise educational spaces to create opportunities for individuals to engage in dialogue and "confront each other with their respective memories of trauma, tragedies and triumph" (Jansen, 2009:153). Such opportunities will not only expose "polite silences and hidden resentments" (Jansen, 2009:153) but will also promote open discussion about the harmful nature of indirect knowledge. Resultantly, a sense of ambiguity will inform individuals' experiences, and in so doing serve to catalyse the process of questioning one's ingrained belief systems (Vandeyar & Swart, 2019).

Changing mindsets: Compassionately engaging with diversity in educational spaces

A mindset is a way of thinking, "a disposition or a frame of mind" that comprises a "collection of thoughts and beliefs" that shapes a person's thought processes, which affects how a person thinks, feels and acts (Meier, n.d.:para. 4). It is difficult, but not impossible to change a person's mindset. Various researchers in the field propose different ways of changing mindsets. Jansen (2009) claims that mindsets can be changed through the process of pedagogic dissonance. Pedagogic dissonance happens "when one's stereotypes are shattered" (Jansen, 2009:154). Zembylas (2010:707) advocates for an ethic of discomfort where "teachers and learners critique their deeply held assumptions about themselves and others by positioning themselves as witnesses to social injustices and structurally-limiting practices." Freire (1992:95) proposes that teachers become "transformative intellectuals" and actively assume a "critical democratic outlook on the prescribed content." Postma (2016:5) highlights the non-neutrality of educational spaces "where forgiveness could be cultivated and hope fostered." Vandeyar and Swart (2019:777) advocate for "knowledge of living experience" (Freire, 1992:57) and "proactive commitment to compassionately engage with diversity in educational spaces." Compassionate engagement entails not only a show of empathy, but it should move one to take action to assuage the suffering of another who is stricken by misfortune. Thus, the agentive role of the teacher.

Instilling hope and sustainable peace

The concept "hope" is generally regarded as a positive quality that one needs to cultivate in a person. According to Freire (1994:69), "whatever the perspective through which we appreciate authentic educational practice ... its process implies hope. The hope that we can learn together, teach together, be curiously impatient together, produce something together, and resist together the obstacles that prevent the flowering of our joy." For hooks (2003:xiv) hope "empowers us to continue our work for justice even as the forces of injustice may gain greater power for a time. As teachers we enter the classroom with hope." She argues that "educating is always a vocation rooted in hopefulness"; "we live by hope"; "living in hope says to us, ' There is a way out,' even from the most dangerous and desperate situations" (hooks, 2003:xiv-xv). Both Freire (1992:77) and Jansen (2009:154) claim that "hope is achievable in praxis, if acted upon." Hope is seen as a medium for overcoming despair and reclaiming agency in our pedagogy, to transform society (Jacobs, 2005). Vandeyar and Swart (2019:784) argue that "such transformation not only instils hope, but also holds the promise for sustainable peace."

Thompson (1992:129) aptly sums up how teachers' beliefs inform teachers' practice: "to understand teaching from teachers' perspectives we have to understand the beliefs with which they define their work."

Conclusion

Changing teachers' beliefs will catalyse a change in teachers' practice in a class of diverse learners. In addition to the seven roles of the teacher as identified in the Norms and Standards document (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2000:13-14), I argue that the teacher needs to fulfil and additional role, namely that of a "cultural broker" and a "transformative intellectual." Smith (2016:50) claims that it is fundamental that "teachers have a transformed mind and spirit" when teaching a class of diverse learners. This will create classrooms where the metaphors of "mirrors" and "windows"iv are operationalised; where the hegemonic culture is displaced by "equality of cultural trade" and multiple ways of knowing; where an "asset-based" approach and "funds of knowledge" is embraced; where there is a balance in power relations; where first and second order changes are addressed; where the multiplicity of learner voices are heard; where all learners feel a sense of belonging and a feeling at home and where the spirit of Ubuntu (I am, because of who we all are) prevails - a quality that includes the essential human virtues of compassion and humanity. Teachers are at the forefront of educational change and have the first step in changing the discourse in the classroom to create the beginning of some big changes (Sleeter, 2010). "To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential, if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin" (hooks, 1994:13).

Acknowledgement

This project/publication was made possible by funding received from the National Research Foundation - Grant number 96292.

Notes

i. Born-free refers to a specific generation of South Africans born after 1990, regardless of race, income, or ethnicity, who have no living memory of apartheid.

ii. During the apartheid era, the term Blacks referred to Indian, African and Coloured people of South Africa. The terms Coloured, White, Indian and African derive from the apartheid racial classifications of the different peoples of South Africa. The use of these terms, although problematic, has continued through the postapartheid era in the country. I use these terms grudgingly to help present the necessary context for my work.

iii. These findings were reported earlier (Vandeyar, 2019).

iv. Metaphors of mirrors and windows: Learner identities' need to be affirmed in class. Teachers in a class of diverse learners should create "mirrors" in which learners can see themselves reflected. Teachers should also create opportunities for learners to look out of the "window" to learn about other cultures, even those not present in the class. The classroom is a microcosm of society and the world.

v. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

vi. DATES: Received: 2 December 2020; Revised: 6 October 2021; Accepted: 13 October 2021; Published: 31 December 2021.

References

Abdi H & Asadi B 2015. A synopsis of researches on teachers' and students' beliefs about language learning. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature, 3(4):104-114. Available at https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v3-i4/14.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Amiryousefi M 2015. Iranian EFL teachers and learners' beliefs about vocabulary learning and teaching. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 4(4):29-40. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.680.6483&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Banks JA 2015. Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching (6th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Biesta G 2010. Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. London, England: Paradigm. [ Links ]

Biesta G, Priestley M & Robinson S 2015. The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6):624-640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325 [ Links ]

Blömeke S, Buchholtz N, Suhl U & Kaiser G 2014. Resolving the chicken-or-egg causality dilemma: The longitudinal interplay of teacher knowledge and teacher beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37:130-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.10.007 [ Links ]

Borg S 2001. Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT Journal, 55(1):21-29. https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/55.1.21 [ Links ]

Bradfield SJ 2013. "Teaching the born frees". Available at https://www.ru.ac.za/history/latestnews/teachingthebornfrees.html. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Braten I & Ferguson LE 2015. Beliefs about sources of knowledge predict motivation for learning in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50:13-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.04.003 [ Links ]

Brizio A, Gabbatore I, Tirassa M & Bosco FM 2015. "No more a child, not yet an adult": Studying social cognition in adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 6:1011. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01011 [ Links ]

Bryan LA 2012. Research on science teacher beliefs. In BJ Fraser, KG Tobin & GJ McRobbie (eds). Second international handbook of science education (Vol. 1). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9041-7 [ Links ]

Burner T 2018. Why is educational change so difficult and how can we make it more effective? Forskning & Forandring, 1(1):122-134. https://doi.org/10.23865/fof.v1.1081 [ Links ]

Burr V 2003. Social constructionism (2nd ed). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler-Kisber L 2010. Qualitative inquiry: Thematic, narrative and arts-informed perspectives. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Cabaroglu N & Roberts J 2000. Development in student teachers' pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. System, 28(3):387-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(00)00019-1 [ Links ]

Campbell C, Lieberman A, Yashkina A, Alexander S & Rodway J 2018. Teacher learning and leadership program: Research Report 2017-2018. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Teachers' Federation. Available at https://www.otffeo.on.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/11/TLLP-Research-Report-2017-2018.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Cawe ZN 2014. The "born-free"fallacy. Available at www.bonfiire.com/stellenbosch/2014/03/the-born-free-fallacy/. Accessed 10 May 2017. [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ & Connelly FM 2000. Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Czaika M & De Haas H 2014. The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory. International Migration Review, 48(2):283-323. https://doi.org/10T111/imre.12095 [ Links ]

Datnow A & Park V 2018. Professional collaboration with purpose: Teacher learning towards equitable and excellent schools. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351165884 [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2000. National Education Policy Act (27/1996): Norms and Standards for Educators. Government Gazette, 415(20844), February 4. [ Links ]

Donaldson G 2015. Successful futures: Independent review of curriculum and assessment arrangements in Wales. Cardiff, Wales: Welsh Government. Available at https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-03/successful-futures.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Erikson EH 1968. Identity, youth, and crisis. New York, NY: Norton. [ Links ]

Etherington K 2007. Ethical research in reflexive relationships. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(5):599-616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407301175 [ Links ]

Fataar A 2018. Decolonising education in South Africa: Perspectives and debates [Special issue]. Educational Research for Social Change, 7:vi-ix. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/ersc/v7nspe/01.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Fives H & Buehl MM 2008. What do teachers believe? Developing a framework for examining beliefs about teachers' knowledge and ability. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(2):134-176. https://doi.org/10T016/jxedpsych.2008.01.001 [ Links ]

Fives H & Buehl MM 2012. Spring cleaning for the "messy" construct of teachers' beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In KR Harris, S Graham & T Urdan (eds). APA educational psychology handbook (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13274-019 [ Links ]

Fives H & Gill MG (eds.) 2015. International handbook of research on teachers' beliefs. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fox EW & Maggioni L 2014. When it is also about you: The potential for fostering epistemic development in a cognitive development class. Paper presented at the American Education Research Association annual conference, Philadelphia, PA, 3-7 April. [ Links ]

Freire P 1992. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. London, England: Continuum. [ Links ]

Freire P 1994. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. London, England: Continuum. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2000. The return of large-scale reform. Journal of Educational Change, 1(1):5-27. https://doi.org/10T023/AT010068703786 [ Links ]

Fullan M 2001. The new meaning of educational change (3rd ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2007. The new meaning of educational change (4th ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2009. Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Educational Change, 10:101-113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z [ Links ]

Goodson I 2014. Context, curriculum and professional knowledge. History of Education, 43(6):768-776. https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2014.943813 [ Links ]

Goodson IF & Hargreaves A 1996. Teachers' professional lives. London, England: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Hall S 1993. Old and new identities, old and new ethnicities. In AD King (ed). Culture globalization and the world-system. London, England: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hall S 1994. Cultural identity and diaspora. In P Williams & L Chrisman (eds). Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory: A reader. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Hargreaves A & Ainscow M 2015. The top and bottom of leadership and change. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(3):42-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721715614828 [ Links ]

Hargreaves A & Fullan M 2012. Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Harris A & Jones M 2019. Teacher leadership and educational change. School Leadership & Management, 39(2):123-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1574964 [ Links ]

Haydon G, Brown G & Van der Riet P 2018. Narrative inquiry as a research methodology exploring person centred care in nursing. Collegian, 25(1):125-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2017.03.001 [ Links ]

Hendriks H, Van den Putte B & De Bruijn GJ 2015. Subjective reality: The influence of perceived and objective conversational valence on binge drinking determinants. Journal of Health Communication, 20(7):859-866. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018570 [ Links ]

hooks b 1994. Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

hooks b 2003. Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hsieh HF & Shannon SE 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9):1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687 [ Links ]

Jacobs D 2005. What's hope got to do with it?: Toward a theory of hope and pedagogy. JAC: A Journal of Composition Theory, 25(4):783-802. Available at https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/englishpub/11. Accessed 20 March 2018. [ Links ]

Jansen JD 2002. Political symbolism as policy craft: Explaining non-reform in South African education after apartheid. Journal of Education Policy, 17(2):199-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110116534 [ Links ]

Jansen JD 2009. Knowledge in the blood: Confronting race and the apartheid past. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Johnson MD & Horne RM 2016. Temporal ordering of supportive dyadic coping, commitment, and willingness to sacrifice. Family Relations, 65(2):314-326. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12187 [ Links ]

Khader FR 2012. Teachers' pedagogical beliefs and actual classroom practices in social studies instruction. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(1):73-92. Available at http://aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_1_January_2012/9.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Khan I, Mehmood A & Jumani NB 2018. The relationship of instructional beliefs of teacher educators with their classroom practices in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences 8(1):112-119. Available at https://www.textroad.com/pdf/JAEBS/J.%20Appl.%20Environ.%20Biol.%20Sci.,%208(1)112-119,%202018.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Macnab DS & Payne F 2003. Beliefs, attitudes and practices in mathematics teaching. Perceptions of Scottish primary school teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 29(1):55-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747022000057927 [ Links ]

Marcia JE 1980. Identity in adolescence. In J Adelson (ed). Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Matentjie T 2019. Race, class and inequality in education: Black parents in white-dominant schools after apartheid. In N Spaull & JD Jansen (eds). South African schooling: The enigma of inequality. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18811-5_15 [ Links ]

McLaughlin MW & D Mitra 2001. Theory-based change and change-based theory: Going deeper, going broader. Journal of Educational Change, 2(4):301-323. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014616908334 [ Links ]

Meier JD n.d. What is mindset? Available at https://sourcesofinsight.com/what-is-mindset/. Accessed 5 August 2020. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education (2nd ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mutasa DE 2015. Language policy implementation in South African universities vis-á-vis the speakers of indigenous African languages' perception. Per Linguam, 31(1):46-59. https://doi.org/10.5785/31-1-631 [ Links ]

Nation ISP & Macalister J 2010. Language curriculum design. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nespor J 1987. The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4):317-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027870190403 [ Links ]

Pajares MF 1992. Teachers' beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3):307-332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307 [ Links ]

Peacock M 2001. Pre-service ESL teachers' beliefs about second language learning: A longitudinal study. System, 29(2):177-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(01)00010-0 [ Links ]

Pehkonen E & Pietilä A 2003. On relationships between beliefs and knowledge in mathematics education. Paper presented at the CERME 3: Third conference of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, Bellaria, Italy, 28 February - 3 March. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.566.2269&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Philipp RA 2007. Mathematics teachers' beliefs and affect. In FK Lester Jr. (ed). Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Phipps S & Borg S 2009. Exploring tensions between teachers' grammar teaching beliefs and practices. System, 37(3):380-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.03.002 [ Links ]

Postma D 2016. An educational response to student protests. Learning from Hannah Arendt. Education as Change, 20(1):1 -9. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1042 [ Links ]

Richardson V 1996. The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J Sikula (ed). Handbook of research in teacher education (2nd ed). New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Sandelowski M 2000. Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4):334-340. [ Links ]

Schreiber LM & Valle BE 2013. Social constructivist teaching strategies in the small group classroom. Small Group Research, 44(4):395-111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496413488422 [ Links ]

Seale C 2000. The quality of qualitative research. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Serov A 2013. Subjective reality and strong artificial intelligence. ArXiv:1301.6359. Available at https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1301/1301.6359.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Sheehy G 1981. Path finders: How to achieve happiness by conquering life's crisis. London, England: Sidgwick & Jackson. [ Links ]

Sleeter CE 2010. Decolonizing curriculum. Curriculum Inquiry, 40(2):193-204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2010.00477.x [ Links ]

Smith T 2016. Make space for indigeneity: Decolonizing education. SELU Research Review Journal, 1(2):49-59. Available at https://selu.usask.ca/documents/research-and-publications/srrj/SRRJ-1-2-Smith.pdf. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]

Tang ELY, Lee JCK & Chun CKW 2012. Development of teaching beliefs and the focus of change in the process of pre-service ESL teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(5):90-107. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n5.8 [ Links ]

Taylor S 2019. How can learning inequalities be reduced? Lessons learnt from experimental research in South Africa. In N Spaull & JD Jansen (eds). South African schooling: The enigma of inequality. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18811-5_17 [ Links ]

Thompson A 1992. Teachers' beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of the research. In DA Grouws (ed). Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning. New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Vandeyar S 2017. The teacher as an agent of meaningful educational change. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 17(2):373-393. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.2O314 [ Links ]

Vandeyar S 2019. Retirando das caixas os "nascidos livres": A liberdade de escolher as identidades [Unboxing "born-frees": Freedom to choose identities]. Ensaio Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 27(104):456-475. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362019002702196 [ Links ]

Vandeyar S 2020. Why decolonizing the South African university curriculum will fail. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(7):783-796. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1592149 [ Links ]

Vandeyar S 2021. Pedagogy of compassion: Negotiating the contours of global citizenship. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 35(2):200-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2021.1880991 [ Links ]

Vandeyar S & Swart R 2016. Education change: A case for a 'pedagogy of compassion'. Education as Change, 20(3):141-159. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1362 [ Links ]

Vandeyar S & Swart R 2019. Shattering the silence: Dialogic engagement about education protest actions in South African university classrooms. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(6):772-788. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1502170 [ Links ]

Vygotsky LS 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Xu L 2012. The role of teachers' beliefs in the language teaching-learning process. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(7):1397-1402. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.27.1397-1402 [ Links ]

Zembylas M 2010. Teachers' emotional experiences of growing diversity and multiculturalism in schools and the prospects of an ethic of discomfort. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice,16(6):703-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517687 [ Links ]

Zhao Y 2011. Students as change partners: A proposal for educational change in the age of globalization [Special issue]. Journal of Educational Change, 12(2):267-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9159-9 [ Links ]

Zheng H 2009. A review of research on EFL pre-service teachers' beliefs and practices. Journal of Cambridge Studies, 4(1):73-81. Available at https://aspace.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/255675/200901-article9.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 December 2021. [ Links ]