Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 suppl.1 Pretoria Oct. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41ns1a1831

ARTICLES

Language as contextual factor of an education system: Reading development as a necessity

Elize VosI; Nadine FoucheII

IFaculty of Education, School for Languages in Education, North-West University, Potehefstroom, South Africa. elize.vos@nwu.ac.za

IIVirtual Institute for Afrikaans (VivA), South Africa

ABSTRACT

Language is a contextual factor of an education system as it determines the Language of Learning and Teaching (LOLT). In order to provide for diversity in South Africa, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, makes provision for 11 official languages and the Language in Education Policy (LiEP) promotes respect for not only these official languages, but languages in general as well as the preservation of cultural diversity by means of multilingualism. Having measures like these in place creates the assumption that different languages are used as LOLT. However, mother tongue education is not fully realised in South Africa. A large percentage of learners' LOLT is not their home language. This lack of mother tongue education may cause poor reading ability. South Africa's government and Department of Education (DoE) has certain strategies available to promote reading, however, the feasibility of these strategies is questionable when the poor reading performance of South African learners is taken into account. To find a solution for the above-stated problem, due to the fact that reading plays an important role within an education system, and the integral part it forms in nation-building, we conducted a literature study to identify current national and international reading strategies. In this article we present a synthesis of these strategies, which we refer to as a reading motivation framework, outlining the responsibilities of various social role players.

Keywords: contextual factor; education system; reading development; reading motivation framework

Introduction

Reading is a vital skill in being able to function as a member of a national and international society (One World Literacy Foundation [OWLF], 2013) and should, therefore, be promoted. Empathy with characters is developed while reading - a skill that is transferred to our daily lives to "function as more than self-obsessed individuals" (Gaiman, 2013:para. 16). A process of transformation, according to Gogan (2017:46), also takes place during the reading process because of its receptive nature (readers engage, interpret and respond to texts), relational nature (readers relate text to context) and recursive nature (readers revisit, return to and literally re-course through text).

In spite of reading's important transformation ability, and the fact that reading promotes confidence to act as a member of a national and world community, the reading ability of learners in many nations still remains problematic. This is evident from the Programme for International Student Assessment 2015 (PISA)i results, an ongoing triennial survey that assesses the extent to which 15-year-old learners near the end of compulsory education have acquired key knowledge and skills that are essential for full participation in modern societies (regardless of the school type and grade attended). A total of 72 countries and economies (of which South Africa was one) formed part of the 2015 PISA survey. It was clear that across these countries and economies, only 8.3% of learners were top performers in reading. Twenty per cent of the learners who participated in the 2015 PISA survey did not attain the baseline level of proficiency in reading, considering the level of proficiency where learners begin to demonstrate the reading skills that will enable them to participate effectively and productively in life.

The poor performance of South African learners is also evident from the most recent Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016 (PIRLS) results. The PIRLS assessment is coordinated by the International Association for Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) and is used to assess the reading ability of Grade 4 learners. The collected data make it possible to compare different countries and education systems with regard to reading. Compared to those of other countries, the South African PIRLS results were worrying, as they were the weakest out of more than 50 countries, scoring only 320 points, which is significantly below the PIRLS centre point of 500. These results indicate that South Africa was approximately 6 years behind the top-performing countries. The results also indicate that 78% of South African Grade 4 learners, compared to only 4% internationally, did not have basic reading skills. They could not read for meaning or retrieve basic information from the text. Only 2% of South African learners attained the advanced benchmark, compared to 10% internationally (Howie, Combrinck, Roux, Tshele, Mokoena & McLeod Palane, 2017). In other words, only 2% of South African learners could "integrate ideas as well as evidence across a text to appreciate overall themes, understand the author's stance and interpret significant events" (Howie et al., 2017:4).

In South Africa, the Annual National Assessments (ANAs) are standardised national assessments for literacy and numeracy for the Foundation Phase (Grade 1 to 3). Language and mathematics are also assessed in the Intermediate Phase (Grade 4 to 6) and in the Senior Phase (Grade 7 to 9). The question papers and memoranda are supplied by the National Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the schools manage the conduct of the tests as well as the marking and internal moderation. According to the 2013 ANA Diagnostic Report, specific gaps in skills, knowledge and competencies regarding reading comprehension were identified. The DBE, Republic of South Africa (RSA) (2013) lists problems regarding to learners' reading comprehension, which include poor reading and comprehension skills, as well as low reading levels (Foundation Phase); a lack of understanding of the events in a story and different figures of speech, an inability to summarise a story, analyse a text or identify the lesson of a story (Intermediate Phase); an inability to interpret the meaning of or give an opinion about different texts, difficulty explaining concepts in information texts and identifying the topic sentence of a paragraph and distinguishing the main points from supporting detail, a lack of understanding of idioms and expressions, as well as figures of speech, and insufficient vocabulary to comprehend their meaning (Senior Phase).

Eloff (2017) argues that one of the factors responsible for the poor reading performance of South African learners is the lack of mother tongue education. Despite the government's commitment to multilingualism and the promotion of all 11 official languages in public sectors, data indicate that while 67.6% of learners in the school system used English as their LOLT, this was the home language of only 7.8% of those learners (Olivier, 2009).

The above-mentioned situation exists even though there are measures in place, such as the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (RSA, 1996c) (hereafter referred to as the Constitution), the South African Schools Act (Act no. 84 of 1996) (RSA, 1996a) and the LiEP (Act no. 27 of 1996) (RSA, 1996b). These measures ensure national integration by protecting diversity, creating a democratic environment and promoting equality and basic human rights through language, among other things (Le Cordeur, 2011). The aforementioned acts were required due to the diverse linguistic nature of South Africa which is evident by the almost 58 million South Africans (Statistics South Africa, RSA, 2018) who speak at least 24 home languagesii (Du Plessis, 2000; Raidt, 1991; Steyn, Wolhuter, Vos & De Beer, 2017). A total of 11 languages are regarded as official languages (RSA, 1996c).

The Constitution (RSA, 1996c) states that provision should be made for the promotion and development of the use of all 11 official languages, the Khoi, Nama and San languages, as well as Sign Language. The Constitution also stresses the promotion of and respect for all languages used in South African communities, such as German, Greek and other languages used for religious purposes. Furthermore, s. 29 of the Constitution (RSA, 1996c) states that "everyone has the right to receive education in the official language or languages of their choice in public educational institutions where that education is reasonably practicable." The South African Schools Act (Act no. 84 of 1996) (RSA, 1996a) also ensures the acknowledgement of linguistic diversity by following an inclusive approach to language policy. This approach can be seen by the recognition of Sign Language as an official language for purposes of learning at a public school (DBE, RSA, 2010).

The LiEP (Act no. 27 of 1996) (RSA, 1996b) states that cultural diversity is a national asset that should be promoted by multilingualism, the development of the official languages and respect for all languages used in the country, including South African Sign Language and the languages referred to in the Constitution. This policy also stresses the conservation of home language(s), while providing access to and the effective acquisition of additional language(s).

However, we are faced with the situation where 59.7% of South African learners receive instruction and are assessed in a language that is not spoken most frequently at home (Olivier, 2009). D'Oliveira (2003) explains a number of reasons for this discrepancy between the actual language used at home and the LOLT. Firstly, parents choose the LOLT on behalf of their children. They expect their children to be taught in English, because it is regarded as the lingua francaiii within the South African context. Secondly, this discrepancy is due to the fact that the LOLT is part of an unalterable, pre-agreed package determined by the school governing body, according to the South African Schools Act (Act no. 84 of 1996) (RSA, 1996a). Despite the linguistically changing environment, some schools maintain the original LOLT, partly as a method to exclude certain races, while others argue that in keeping the original LOLT, the ethos of the school is maintained. Lastly, the abrupt shift to the LOLT in Grade 4 can also be regarded as a contributing factor to this disparity. The current situation in South Africa is that learners start using English as LOLT in Grade 4 (MacKay, 2014; Spaull, Pretorius & Mohohlwane 2018). The result of this shift is that neither language (home language or the new LOLT) is properly developed. The transition from formal instruction in the home language to instruction in a first or second language may lead to home language acquisition being attenuated or even lost.

According to Ball (2010), learners need fluency and literacy in their home language which lay a cognitive and linguistic foundation for learning additional languages. Mastering a home language makes learners capable of mastering basic skills (reading and communicating) and more complex, abstract academic concepts and skills and enable them to transfer this knowledge and skills to other language contexts (Prinsloo, 2007; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2006). According to Owen-Smith (2010), without a solid foundation in the home language, it is not surprising that less than 30% of African language students learning through English achieve a Grade 12 certificate. Insufficient knowledge regarding the vocabulary of the LOLT limits optimal reading comprehension (Bornman, Pauw, Potgieter & Janse van Vuuren, 2017; Hoadley, 2015).

The research aim of the article was not to propose changes to language policy with regard to LOLT, but to ensure that reading is promoted, regardless of whether the LOLT is the home language of the learner. Reading as a component of literacy is directly related to employment: In their survey of adult skills, the OECD found that individuals who can make "complex inferences and evaluate subtle truth claims or arguments in written texts" earn an hourly wage of 60% more than their peers who are only capable of reading short texts to retrieve a single piece of information (OECD, 2013:3). Consequently, the aim of this article was to integrate the best reading practices from international and national reading strategies into a reading motivation framework which indicates the specific reading motivation strategies that various social role players can use to promote the reading motivation of learners. Furthermore, the content of this article is aimed at raising policymakers' awareness of the necessity of a well-designed reading motivation framework as part of an education system.

Literature Review

International strategies

The Concept Orientated Reading Instruction (CORI) model, as discussed by Guthrie, Klauda and Ho (2013), seems to be an effective reading instruction programme to improve the reading motivation of learners that has been successfully implemented in classrooms in the United States of America (USA). The participation of the USA in the 2016 PIRLS indicated that 96% of their learners can read properly. The CORI model is based on six principles, namely:

• reaching goals by using suitable and readable reading texts;

• enabling learners to choose their own reading material;

• initiating cooperation between learners;

• emphasising the importance of reading;

• explaining the relevance of reading texts; and

• organising texts according to thematic units. Another successfully implemented reading programme is Pilgreen's Sustained Silent Reading Programme (SSR) (2000), which involves silent reading time by learners of about 15 to 30 minutes twice a week during which they read their own reading material for enjoyment resulting in self-regulated reading and reading becoming a habit and not merely a classroom activity. Reading material should consist of various texts and should be made available by the teacher. The teacher should be a role model by also reading during the silent reading time. The teaching and assessment of reading should be avoided. The only requirement is that learners should keep reading records. Garan and DeVoogd (2008:337) defined SSR as "a time devoted to free reading during which students read books of their own choice, without assessment, skills work, monitoring, or instruction from the teacher." The focus is on becoming familiar with reading and developing confidence in reading.

National strategies

In this regard, the National Reading Strategy (NRS) (DoE, RSA, 2008), The Read to Lead Campaign (RLC) (DBE, RSA, 2014) and the Shine Literacy Hour (Hickman, 2018) can be referred to as national reading strategies.

In developing the NRS (DoE, RSA, 2008), South Africa participated in a number of United Nations development campaigns. These included the UNESCO Literacy Decade 2003 to 2013 and the Education for All campaign, which aimed to have increased literacy rates by 50% by the year 2015. Underpinning these campaigns, are the millennium development goals (MDGs). Literacy promotion is at the heart of the MDGs. The purpose of the NRS was to put reading firmly on the school agenda, to clarify and simplify curriculum expectations, to promote reading across the curriculum, to affirm and advance the use of all languages, to encourage reading for enjoyment and to ensure that not only teachers, learners and parents, but also the broader community, understand their role in improving and promoting reading. Although the NRS focuses largely on primary school learners, it recognises that learning, especially the development of reading skills, is a life-long practice that continues into high school and beyond. The responsibility of the DBE with regard to the successful implementation of the NRS includes the monitoring of learner performance, improving teaching practice and methodology, training, developing and supporting teachers, managing the teaching of reading, supplying resources for and promoting research about reading and forming partnerships with universities and other specialist reading organisations (DoE, RSA, 2008).

The RLC (2015 to 2019) is a follow-up strategy of the DBE (DBE, RSA, 2014) for promoting reading. According to this campaign, reading has to be both the height of fashion and a lifestyle choice. Libraries have to be functional and well equipped with technology. Learners have to read on their level of development. The emphasis has to be on reading that promotes learning that enables the individual to attain a successful career and, therefore, take part in democracy. According to the purpose of the RLC, literacy levels have to increase to 75%. Social role players identified for achieving these reading goals are the DBE, schools, parents and caretakers, as well as spiritual and community organisations.

The Shine Literacy Hour (Hickman, 2018) is a targeted literacy teaching programme delivered in selected disadvantaged primary schools focusing on learners in Grade 2 and 3 targeted on extra support with their reading, writing and speaking. Since its establishment in 2000 they have set up the Khanyisa programme, which aims to provide children in Grade 2 with more opportunities to read and enjoy books. This part of the programme is delivered by unemployed, trained matriculants who work alongside Grade 2 teachers. The principles underlying Shine Literacy are outlined below.

Select relevant texts which are of interest to the learners, because this promotes reading for enjoyment. By doing this, learners also develop a positive reader identity: the belief of being capable of understanding texts and the skill of valuing texts. A positive reader identity in turn promotes intrinsic motivation.

Create opportunities for shared reading. This enables learners to engage with books that expose them to aspects that do not form part of their everyday life. At the same time, they develop empathy, engage with language, as well as with concepts and information that would otherwise not be accessible. In this regard, creating time to engage with texts is also worth mentioning, because this promotes the ability to learn to read. This interaction can take the form of paired reading which typically involves an adult or stronger reader, reading a book or text aloud with the child until the child is confident enough to read alone. This in turn improves the confidence of learners to read alone.

Extended conversations need to take place around the book or given text. This can take the form of observations, expansions and open-ended questions. Various skills are developed by using extended conversations, namely oral skills, reading comprehension, higher-order thinking skills such as abstraction, reasoning, and making inferences. Learners also receive validation for their efforts.

Teachers should also ensure that readers at the correct level are used in the language classroom. This provides for the diversity of the learners in the class, leading to regular, independent reading.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework underpinning this article is Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). Bronfenbrenner emphasises factors in the learner's wider social, political and economic environment as important role players in learner development and learner motivation. "According to Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory, children typically find themselves enmeshed in various ecosystems, from the most intimate home ecological system to the larger school system, and then to the most expansive system which includes society and culture" (The Psychologist Notes Headquarters, 2019:para. 3). His theory thus emphasises the important interaction between a learner and the changing environment in which s/he lives. He systematises environmental influences as follows:

• Microsystem: immediate environments (family, school, peer, neighbourhood, and child care environments).

• Mesosystem: it refers to the connections between the child's immediate environments (learner's home and school).

• Exosystem: external environmental contexts that indirectly influence the learner's development (parents' work environment).

• Macrosystem: the larger and more distant collection of people and places to the children that still influences them (the larger cultural environment, their beliefs and ideas, as well as national economy, political culture).

• Chronosystem: patterns of environmental events and transmission during life.

This theory is relevant to this article as we are of the opinion that learners' reading development is not only determined by one person, the teacher, even though this is regarded as the most important social role player. Various social role players contribute to the creation of a positive reading climate conducive to reading development and reading motivation. These social role players can be allocated specifically to Bronfenbrenner's (1994) micro- and macrosystem:

• Microsystem: parents, teacher, principal, and management team

• Macrosystem: DBE.

Methodology

The research methodology used in this study can be described as non-empirical (Mouton, 2001). A non-empirical research methodology is a methodology that focuses on the construction of theories and models; the analyses of concepts, scientific data or statistics; as well as a critical overview of the status of a given phenomenon (Mouton, 2001).

This methodology was selected, because we aimed to construct a model (a reading motivation framework) that could be used in the school and classroom setting. These contexts are regarded as important external factors which influence reading motivation (Irvin, 1998; Olen & Machet, 1997; Scheffel, Shroyer & Strongin, 2003; Snow, Barnes, Chandler, Goodman & Hemphill, 1991). However, the important role of the Education Department cannot be omitted, as this institution has a direct influence on the principal and the management team, as well as on the teachers (the most important role players). The relevance of parents as social role players can also not be left out of consideration.

With these social role players in mind, we conducted a comprehensive literature study to determine the best reading practices from international and national reading strategies. The findings that resulted from the literature study were integrated into a reading motivation framework, indicating the reading motivation strategies that each social role player can use to promote the reading motivation of learners.

In order to find recent and relevant sources for the literature study, an EBSCOHost Academic search with the following English key terms (and their Afrikaans equivalents) was launched: choice of reading texts, external and internal factors, extrinsic motivation, interests, intrinsic motivation, language education, reading assessment, reading culture, reading engagement, reading motivation, reading strategies, reading and group work, reading and technology.

A second EBSCHOHost Academic search using the same key terms was conducted to find more recent and relevant information from theses, journals, and other primary and secondary sources of information. The search was expanded using Google Scholar. The references of sources that were identified as being key sources, were searched to find all recent research on the research topic.

The main benefit of doing a literature study is to provide the reader with a mosaic of what is happening concerning a given topic (Perry, 2006). The literature review is thus regarded as a source for generating data.

The Proposed Reading Motivation

Framework

Reading is important because individuals who know how to read can become informed and educate themselves to become valuable members of society (OWLF, 2013). The proposed reading motivation framework is a means to improve language as a contextual factor of an education system. This framework consists of specific reading motivation strategies which various social role players in the school and classroom environment (the DBE, the school principal and management team, teachers and parents) can implement to improve readers' reading motivation levels.

Discussion of the Reading Motivation Framework: Strategies that Various Social Role Players can Implement

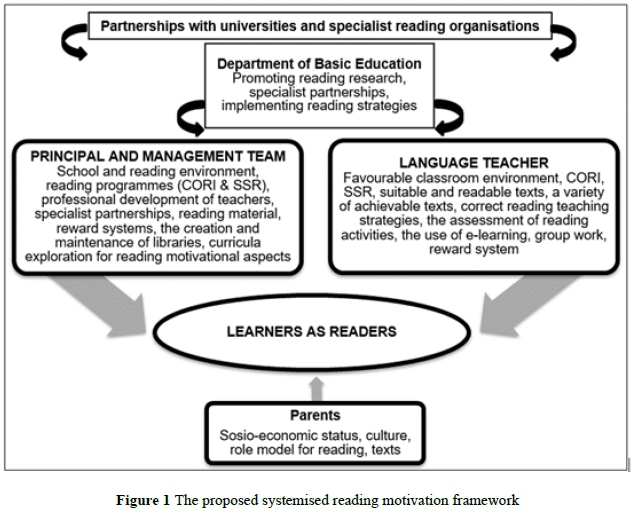

The identified social role players and strategies that emanated from the literature study are systematised in the reading motivation framework in Figure 1 and are discussed in detail in the following section.

Parents

Although the parental home is not part of the school and classroom environment for which the reading motivation framework is developed and intended, the home is the first place where the child is exposed to reading. It is the parents' responsibility to choose the "right book" for their child. The "right book" stimulates the interest of the child and the idea that reading is an enjoyable activity (Robertson, 2017:187).

Reach Out & Read (2015) shows the important role of parents reading aloud to children. This improves the literacy and language ability of their children, increases motivation and stimulates curiosity. In addition, reading aloud to children contributes to the processing of anxiety, expands their world perspective and creates a positive association with books and reading. Further reading motivation strategies that parents can include are: taking children to the library at an early age and having pleasant times reading books together, reducing and limiting children's exposure to social media (Van Vuuren, 2007), providing as much reading material as possible to children, acting as good reading role models and conducting meaningful conversations about the content of children's reading activities to stimulate and develop critical reading assessment skills and visual literacy.

The Department of Basic Education

The DBE should regularly initiate research on reading and establish partnerships with universities and specialist reading organisations to support and strengthen reading campaigns among social role players. The DBE should approach specialist teachers (experts in reading) to assist in the choice of textbooks and prescribed works, as they have first-hand knowledge of learners' reading preferences.

The necessity of a national reading strategy can annually be highlighted in the media and communicated to the social role players. In this regard, the NRS (DoE, RSA, 2008) and the RLC (DBE, RSA, 2014) can be referred to as national reading strategies (refer to the literature study section where these strategies are thoroughly discussed).

Principal and Management Team

The principal and the management team are solely responsible for creating, not only a stimulating school and learning environment, but also a favourable reading atmosphere of high standard. They should constantly keep the learners, parents and teachers motivated and establish collaboration between them. A positive attitude towards reading and the reading strategies of the DBE (including the NRS and RLC) should also be established and they, as leadership figures and role models, should aim to actively promote these through support and recognition systems. The principal remains the person responsible for the reading programme of the school.

The principal should analyse the learners' reading results and involve the parents in the school's reading programme. A careful analysis of the ANAs will indicate school and learner performance, as well as the best and weakest reading practices, for the purpose of providing information on intervention strategies. The allocation and effective use of reading time should be managed by the principal. The role players should ensure that, according to the stipulations of the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) (DBE, RSA, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c), every learner from Grade 4 to 12 should have his or her own prescribed reading material.

Furthermore, the principal should ensure that the development of reading is included in the school policy. In this regard, it is emphasised that the learners' reading motivation is a whole-school responsibility. According to Cullen (2016) different discipline-specific literacy strategies can be used by teachers to help learners improve their understanding of different course content.

Compulsory weekly silent reading time can be scheduled on the school timetable for all the grades, during which all the subject teachers should ensure that each learner reads for his or her own enjoyment. The principal and the management team can use such compulsory weekly silent reading times as a marketing strategy for the school. The school library should be maintained and regularly supplied with new books. If the school does not have a library, the principal should encourage the teachers to gradually establish subject-specific class libraries where the reading material can be utilised during the weekly silent reading time. This process will, however, be financially challenging. The principals of schools with hostels can encourage the supervisory staff to provide reading material for the residents. An annual reading week or month during which well-known authors and poets are invited to give talks to learners will increase the reading motivation of the learners.

Although the principal and the management team are primarily responsible for creating a favourable school and learning environment, the facilitation of reading is the language teacher's main challenge.

Language Teacher

According to the DBE, RSA (2013), research proves that the most important factor for learners' reading motivation and their final reading ability is the capability of the language teacher to give good reading instruction.

A language teacher should create a favourable classroom environment in which he or she focuses especially on the motivation, dedication and teaching of the learners, so that they can develop into self-directed learners.

The language teacher should promote reading pleasure in class and create a class atmosphere in which learners feel free to give their opinions on certain aspects in texts. According to Sweet and Guthrie (1996), the teacher should focus on intrinsically motivating learners to read and be careful about a reward system. Deci (1971) found that extrinsic rewards deprive learners of intrinsic motivation. According to Stipek (2002) it is better to set short-term goals which are consistent with learners' abilities and skills. If learners achieve these goals, their intrinsic motivation is increased, ultimately leading to the establishment of good reading habits. This does not imply that language teachers should refrain from using rewards, but should first attempt to increase the learners' intrinsic motivation. Alternatively, extrinsic rewards challenge learners to take on more difficult tasks. However, the use of this is only a short-term strategy, which should be discussed with the learners beforehand. The teacher should ensure that the rewards are within reach of all learners and not only the top achievers. Extrinsic reading-related rewards can also be used in the language classroom (Cameron & Pierce, 1994). Reading-related rewards are especially encouraged by Marinak and Gambrell (2008:23): "[T]he type of reward -specifically the proximity of the reward to the desired behaviour - should be carefully considered when using rewards in the classroom. If the desired behaviour is reading, rewards that are proximal to engaging with books should be offered ..."

The teacher can encourage the learners to reward themselves when a particular reading objective has been reached. When rewards are ultimately combined with a learner's goals, it provides the learner with maximum success. In this way, the rewards contribute to the learner's own sense of reading competence. However, when the teacher regularly uses rewards, it is necessary to decrease it systematically and gradually focus more on intrinsic motivation.

Furthermore, to develop intrinsically-motivated readers, language teachers should constantly take into account the reading needs and diversity of the learners, and continuously develop their reading motivation. Reading material should reflect the individuality of the learner; the learner should be able to identify with the content; and the reading material should address a variety of aspects according to the learner's developmental stage. When learners are allowed a choice of reading texts, their intrinsic motivation is increased. Learners will be more willing to read texts that reflect their field of experience, interests and needs, as well as reading texts that contain lively imagery. According to the Ontario Ministry of Education ([OME], 2003), a stimulating and diverse reading environment should be created where the reading material reflects the cultural diversity of the school and the community. The time limit sometimes set by teachers to read a text can demotivate learners. The teacher should allow enough time for reading texts, as this will increase the learners' levels of reading competence.

Gender differences should also be taken into account. According to Duckworth and Seligman (2006), Eccles, Wigfield, Harold and Blumenfeld (1993), Marsh (1989) and Wigfield, Eccles, Yoon, Harold, Arbreton, Freedman-Doan and Blumenfeld (1997), girls have higher levels of reading competence, they recognise the value of reading and their higher academic achievement can be attributed to their self-discipline. Girls are more involved in reading activities, will talk to their friends about what they have read and indulge in reading. Boys, on the other hand, are not as indulgent as girls when it comes to reading as they are more competitive with regard to reading.

According to Bandura's socio-cognitive theory (1982), the relationship between goal setting and self-esteem is an important source of learner motivation. In this regard, it is important that the language teacher will prepare the first reading task at the beginning of the new school year or term in such a way that the learners can master it. If the learner is exposed to an easier reading task, one that he or she can accomplish, and more difficult reading tasks are added systematically, the learner's self-esteem (or literacy) levels are increased in the process and he or she starts to enjoy reading activities, which is indicative of intrinsic motivation with regard to a reading task.

In addition, achievable reading tasks can be created using clear instructional verbs of which the meaning is clear to the learner. A list of instruction verbs, with the explanation and requirements of each, can be provided to the learners at the beginning of the year. Teachers should strive to keep reading tasks and assignments interesting. The traditional worksheet can be replaced with open-ended activities. The OME (2003) recommends that reading should be incorporated into other activities to demonstrate to learners that reading is an essential skill with practical value in various contexts. Teachers should also provide critical reading skills in the compilation of reading tasks. Consequently, the teacher should pose questions that focus on the cultural and political analysis of a reading text. In this regard, Robertson (2017) mentions that learners should be encouraged to verify the facts that are presented, especially in informational texts, and that learners should question the choices made by the authors of these texts. Providing feedback upon completion of a reading task is of paramount importance. Feedback can take the form of direct verbal encouragement or even written feedback.

The teacher should check the learners' reading comprehension regularly, ask questions during the reading of the text and teach the learners to summarise the contents at the end of the reading. The teacher should guide the learners to formulate syntheses with reference to other texts and sources. Learners' prior knowledge should be activated and the teacher should model how the important sections in a text are identified. Learners need to create sensory images of the text. The teacher should demonstrate how to draw connections in a text and how to make predictions of events. The CAPS (DBE, RSA, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c) is based on the principle of the International Reading Association (IRA) that no single method or single combination of methods exist according to which reading can be taught to all learners. Therefore, teachers should not only have a thorough knowledge of a variety of teaching methods, but should also thoroughly know each learner in order to use the appropriate reading method for each. Learners should have the following knowledge and skills to read fluently and with comprehension: prior knowledge and experience, an understanding of the concepts of printing, and knowledge about phonemic awareness, letter-sound relationships, vocabulary, semantics and syntax, metacognition and higher-order thinking abilities. The learner should apply his or her cognitive strategies in an adaptable manner to gain, monitor, regulate and sustain reading comprehension. In the instruction of reading texts, the teacher should pay attention to the pre-reading, during-reading and post-reading phases of the reading process which are prescribed in the CAPS (DBE, RSA, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c). Lawrence, Le Cordeur, Van der Merwe, Van der Vyver and Van Oort (2014) provide a concise description of each of these reading phases and of the different reading strategies to be used in each phase. It is important for the teacher to explain to the learners in the pre-reading phase that vocabulary knowledge is important for better reading comprehension. Furthermore, in the pre-reading phase, the learners are introduced to the text. During this phase, the learner can scan the text by, among other things, paying attention to headings and fonts and exploring the book elements (title page, table of contents, chapters and glossary). The information obtained from scanning the text is used to make predictions about the content. During reading, the learner should be given the opportunity to gain understanding of the text by asking and answering questions, visualising events and making deductions. The teacher should monitor to what extent the learners understand the text, therefore, it is important that the learners should be able to rely on teacher support. During the post-reading phase, learners regard the text as a whole and respond to it self-directedly by either summarising or answering lower to higher cognitive questions. The learner should be able to employ his or her critical reading skills during this reading phase by investigating links and associations, drawing conclusions, evaluating authors' views and arguments, answering questions raised during the reading of the text and formulating his or her own opinion about the text. In this phase, the learner may be required to reproduce the genre in his or her own writing. Assessment forms an integral part of the various reading phases, especially the post-reading phase. Combs (2012) proposes certain strategies according to which reading comprehension can be assessed with the aim of improving reading comprehension. These are retelling, posing questions, the thinking-out-loud strategy and the cloze technique.

Vos, Nel and Van den Berg (2014) explain that language structures and conventions should not be assessed in reading comprehension tests as such, but as co-determined aspects of reading comprehension construction. The ways in which the questions are formulated should be clear. Questions should be drafted on a 40-40-20% spread of cognitive levels. Questions drafted according to the various cognitive levels challenge the learners according to their skills, and even the weaker readers will feel as if they can master the reading task. Before giving the learners a reading task, it is essential that the teacher first explains the assessment criteria and rubrics to them. A variety of assessment methods should be used for reading tasks, and the learner should be guided to finally assess his or her own reading tasks using the above-mentioned assessment criteria and rubrics. Self-assessment increases the learner's mastering levels. Teachers should guard against assessing abstract knowledge of, among other things, reading comprehension strategies (skimming and scanning) instead of applied skills. According to Fouche (2016) and Vos et al. (2014), the degree of readability of texts should not be determined only by means of readability indices, since readability indices only focus on the structural characteristics of texts without taking into account the degree to which the content is abstract.

Joosten (2012) gives reasons why the teacher can use social media in the classroom environment, including its functionality, it being compliant with pedagogical requirements, the learners being familiar with its use and the fact that information can be created and shared faster and easier. The teacher can also ask the learners to quickly find information on a particular topic on their cell phones. Because many learners have access to dictionary applications on their cell phones, dictionary information is also quickly available during reading comprehension exercises. This can help to expand learners' vocabulary quickly and effectively, especially if there is a shortage of dictionaries in the classroom. The teacher can use electronic learning to develop learners into critical and motivated readers by referring them to specific websites to read articles and have follow-up discussions about these. Teachers can even create a subject-orientated blog where learners can comment on texts. Singh, David and Choo (2012:77-89) are of the opinion that "technologies, interactive and mobile computing" also enable SSR readers with a wider context than "traditional desktop PC [personal computer] interaction."

Reid (2007) indicates that group work within the peer group is particularly motivating. Stipek (2002) points out that the adolescent will rather approach the peer group for help. Collaboration among learners should be initiated by the teacher, as it is important for reading motivation. Prosocial reading objectives can be stimulated during small-group discussions where readers can share their experience of the text with the other learners during discussion groups and book discussions conducted by the readers themselves, during a team effort to design a poster about the text or during a peer group conference during which the learners give feedback.

Peer group discussions are more complex, and within the peer group, learners discover contradictions of text interpretations easier because they have the confidence to ask questions and share their views on the text. McKenna and Dougherty Stahl (2009) recommend interdependent instruction, a strategy where a discussion leader, who has to lead the analysis of a text, is alternately appointed in the group. The learners predict the text content according to the title, subtitle, pictures, bold-printed words and graphic aids. The teacher then reads a pre-determined portion of the text. The learners then discuss the particular section of the text in group format; the discussion leader takes charge and the learners have to explain difficult concepts in the groups. The discussion leader poses questions for the learners to discuss and provide possible answers to, after which the discussion leader summarises the section of text and makes predictions. This is followed by reading the next section of the text, with the next learner in the group acting as the discussion leader.

Conclusion

Language is a contextual factor of an education system due to the fact that it determines the language through which learning and assessment take place within the school system. A reality that 59.7% of South African learners are faced with, is the fact that instruction and assessment occur in a language that is not their home language. This discrepancy can be attributed to (i) parents choosing the lingua franca, English, as LOLT on behalf of a child whose home language is not English, (ii) school governing bodies maintaining the original LOLT to exclude certain races or to maintain the ethos of the school, (iii) and learners speaking African languages switching to another LOLT in Grade 4.

Receiving instruction in a LOLT that differs from learners' home language undermines the development of "a strong foundation of cognitive and academic development in the [home language] that is necessary to provide the stepping stones for learning a second language and to play the 'scaffolding' role needed to assist in the transfer of knowledge to this language" (Owen-Smith, 2010:34). Hoadley (2015:slide 8) also stresses the undermining effect of a LOLT on reading comprehension: "While many children can decode text, few can read sufficiently with understanding, especially in a [first additional language]." Therefore, it is evident that there is a relationship between the LOLT (when it is not the learner's home language) and poor reading performance.

Given the fact that more than 50% of South African learners are instructed in a LOLT that differs from their mother tongue, it is not surprising that the 2016 PIRLS results indicate that 78% of South African Grade 4 learners do not have basic reading skills. Poor reading and comprehension skills are also evident from the 2015 PISA, which indicates that only 8.3% of learners are top performers in reading. In national assessments, such as the ANA, learners' reading performance results are also worrying. According to the 2013 ANA results, poor reading performance is characteristic of all the school phases (Foundation Phase, Intermediate Phase and Senior Phase, and Further Education and Training Phase). On Grade 9 level, learners were not even capable of summarising the content of a story or identifying the topic sentence of a paragraph and distinguishing main points from supporting detail.

These results are worrying given the fact that we are living in an "information glut" economy where people navigate through vast amounts of information daily on the web. Well-developed reading skills is important to function in this type of environment (Gaiman, 2013).

We argue that a possible solution to the above-mentioned problem is the proposed reading motivation framework indicating particular reading motivation strategies that can be implemented by various social role players (the DBE, the principal and management team, teachers, and parents). All the social role players, of which the language teacher is the most important, have the responsibility to promote reading in all aspects of life; we want our learners to be readers, learners, and partners in the world community. The ideal is that this framework should be used to make policymakers aware of the necessity of a well-designed reading motivation framework as part of an education system and consequently be implemented as a reading policy.

Schleicher and Tang (2015:9) refers to the OECD report, Universal Basic Skills: What Countries Stand to Gain, which describes education as "a powerful predictor of the wealth that the country will produce in the long run. Or, put the other way around, the economic output that is lost because of poor education policies and practices leaves many countries in what amounts to a permanent state of economic recession." Perhaps a standardised reading policy is a possible solution for economic prosperity.

Acknowledgement

This research was partially supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (reference number: 112143).

Authors' Contributions

EV and NF wrote the abstract of the article. NF wrote the introduction, the methodology and theoretical framework. EV wrote the literature review and compiled the reading motivation framework (although NF gave input about the language teacher as role player in the framework). EV and NF jointly wrote the conclusion. EV compiled the reference list in accordance with SAJE requirements. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. The PISA tests are conducted in participating countries and economies of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and focus on proficiency in science, mathematics and reading.

ii. The term "home language" refers to the language that is spoken most frequently at home by a learner (DBE, RSA, 2010:3).

iii. The term "lingua franca" refers to a language used among linguistically diverse people to enable communication (Du Plessis, 2000:28).

iv. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

v. DATES: Received: 15 February 2019; Revised: 6 April 2020; Accepted: 19 May 2020; Published: 31 October 2021.

References

Ball J 2010. Educational equity for children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in the early years. Paper presented at the UNESCO International Symposium: Translation and Cultural Mediation, Paris, France, 22-23 February. Available at https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/handle/1828/2457. Accessed 1 June 2018. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2):122-147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 [ Links ]

Bornman E, Pauw JC, Potgieter PH & Janse van Vuuren HH 2017. Moedertaalonderrig, moedertaalleer en identiteit: Redes vir en probleme met die keuse van Afrikaans as onderrigtaal. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, 57(3):724-746. https://doi.org/10.17159/2224-7912/2017/v57n3a4 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1994. Ecological models of human development. In T Husen & TN Postlethwaite (eds). The international encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3). New York, NY: Elsevier Science. [ Links ]

Cameron J & Pierce WD 1994. Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3):363-123. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543064003363 [ Links ]

Combs B 2012. Assessing and addressing literacy needs: Cases and instructional strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cullen KA 2016. Culturally responsive disciplinary literacies strategies instruction. In KA Munger (ed). Steps to success: Crossing the bridge between literacy research and practice. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks. Available at https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/steps-to-success/chapter/12-culturally-responsive-disciplinary-literacy-strategies-instruction/. Accessed 26 February 2020. [ Links ]

Deci EL 1971. The effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1):105-115. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030644 [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2010. The status of the language of learning and teaching in (LOLT) in South African public schools: A quantitative overview. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/The%20Status%20of%20Learning%20and%20Teaching%20in%20South%20African%20Public%20Schools.pdf?ver=2015-05-18-141132-643. Accessed 11 May 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2011a. Kurrikulum- en assesseringsbeleidsverklaring Graad 4-6: Afrikaans Huistaal. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/CurriculumAssessmentPolicyStatements(CAPS)/CAPSIntermediate/tabid/572/Default.aspx. Accessed 12 May 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2011b. Kurrikulum- en assesseringsbeleidsverklaring Graad 7-9: Afrikaans Huistaal. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/CurriculumAssessmentPolicyStatements(CAPS)/CAPSSenior.aspx. Accessed 10 June 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2011c. Kurrikulum- en assesseringsbeleidsverklaring Graad 10-12: Afrikaans Huistaal. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/CurriculumAssessmentPolicyStatements(CAPS)/CAPSFET.aspx. Accessed 10 June 2021. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2013. Annual national assessment of 2013 diagnostic report: First additional language and home language. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2014. Read to lead campaign. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2008. National reading strategy. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/DoE%20Branches/GET/GET%20Schools/National_Reading.pdf?ver=2009-09-09-110716-507. Accessed 11 May 2021. [ Links ]

D'Oliveira C 2003. Moving towards multilingualism in South African schools. In P Cuvelier, T du Plessis & L Teck (eds). Multilingualism, education and social integration: Belgium, Europe, South Africa, Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Duckworth AL & Seligman MEP 2006. Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1): 198-208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.L198 [ Links ]

Du Plessis T 2000. South Africa: From two to eleven official languages. In K Deprez & T du Plessis (eds). Multilingualism and government: Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, former Yugoslavia, and South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Eccles J, Wigfield A, Harold RD & Blumenfeld P 1993. Age and gender differences in children's self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64(3):830-847. https://doi.org/10.1.1467-8624.1993.tb02946.x [ Links ]

Eloff T 2017. We neglect Mother tongue education at our peril. Available at https://www.politicsweb.co.za/opinion/the-elephant-in-the-room-mother-tongue-education. Accessed 25 October 2018. [ Links ]

Fouche N 2016. Cohesion marker usage in the writing of Afrikaans-speaking grade 6 and grade 9 learners. MEd dissertation. Potchefstroom, South Africa: North-West University. [ Links ]

Gaiman N 2013. Why ourfuture depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming. Accessed 20 November 2018. [ Links ]

Garan EM & DeVoogd G 2008. The benefits of sustained silent reading: Scientific research and common sense converge. The Reading Teacher, 62(4):336-344. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.62A6 [ Links ]

Gogan B 2017. Reading as transformation. In AS Horning, DL Gollnitz & CR Haller (eds). What is college reading? Colorado, CO: WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/ATD-B.2017.0001.2.02 [ Links ]

Guthrie JT, Klauda SL & Ho AN 2013. Modeling the relationship among reading instruction, motivation, engagement and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1):9-26. [ Links ]

Hickman R 2018. Supporting South Africa's children to become skilled and enthusiastic readers in the Foundation Phase: A survey of the evidence, with particular reference to Shine Literacy's programmes. Cape Town, South Africa: Shine Literacy. Available at http://www.shineliteracy.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Creating-a-nation-of-readers-a-survey-of-evidence-ePDF.pdf. Accessed 26 February 2020. [ Links ]

Hoadley U 2015. Time to learn [PowerPoint presentation]. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals70/Documents/Reports/Presentation%202%20-%20Time%20to%20Learn%20-Ursula%20Hoadley.pdf?ver=2015-07-07-145433-290. Accessed 19 November 2018. [ Links ]

Howie SJ, Combrinck C, Roux K, Tshele M, Mokoena GM & McLeod Palane N 2017. PIRLS literacy 2016: South African highlights report. Pretoria, South Africa: Centre for Evaluation and Assessment. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326588545_South_Africa_Grade_4_PIRLS_Literacy_2016_Highlights_Report_South_Africa Accessed 22 November 2018. [ Links ]

Irvin JL 1998. Reading and the middle school student: Strategies to enchance literacy. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Joosten T 2012. Social media for educators: Strategies and best practices. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Lawrence D, Le Cordeur M, Van der Merwe L, Van der Vyver C & Van Oort R 2014. Afrikaansmetodiek deur 'n nuwe bril. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Le Cordeur M 2011. Moedertaalonderrig bevorder leerderprestasie en kulturele diversiteit. Beskikbaar te https://www.litnet.co.za/moedertaalonderrig-bevorder-leerderprestasie-en-kulturele-diversiteit/. Geraadpleeg 2 Mei 2018. [ Links ]

MacKay BD 2014. Learning support to grade 4 learners who experience barriers to English as language of teaching and learning. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/14139/dissertation_mackay_bd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 April 2021. [ Links ]

Marinak BA & Gambrell LB 2008. Intrinsic motivation and rewards: What sustains young children's engagement with text? Literacy Research and Instruction, 47(1):9-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070701749546 [ Links ]

Marsh HW 1989. Age and sex effects in multiple dimensions of self-concept: Preadolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3):417-430. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.8L3.417 [ Links ]

McKenna MC & Dougherty Stahl K 2009. Assessment for reading instruction (2nd ed). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Mouton J 2001. How to succeed in your master's and doctoral studies. A South African guide and resource book. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Olen SII & Machet MP 1997. Research projects to determine the effect of free voluntary reading on comprehension. South African Journal of Library & Information Science, 65(2):85-92. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6a4c/74e73b2ee141ebac56364d514e0fcbd4ccd3.pdf. Accessed 27 April 2021. [ Links ]

Olivier J 2009. South Africa: Language and education. Available at http://www.salanguages.com/education.htm Accessed 26 February 2020. [ Links ]

One World Literacy Foundation 2013. Why reading is important? Available at https://www.oneworldliteracyfoundation.org/index.php/why-reading-is-important.html. Accessed 13 March 2019. [ Links ]

Ontario Ministry of Education 2003. Early reading strategy: The report of the Expert Panel on Early Reading in Ontario. Toronto, Canada: Author. Available at http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/reports/reading/reading.pdf Accessed 22 November 2018. [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2013. OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en [ Links ]

Owen-Smith M 2010. The language challenge in the classroom: A serious shift in thinking and action is needed. Focus, 56:31-37. Available at https://hsf.org.za/publications/focus/focus-56-february-2010-on-learning-and-teaching/the-language-challenge-in-the-classroom-a-serious-shift-in-thinking-and-action-is-needed. Accessed 13 November 2018. [ Links ]

Perry FL Jr 2006. Research in applied linguistics: Becoming a discerning consumer. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Pilgreen JL 2000. The SSR-handbook: How to organize and manage a sustained silent reading program. Portsmouth, NH: Boyton/Cook. [ Links ]

Prinsloo D 2007. The right to mother tongue education: A multidisciplinary, normative perspective. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 25(1):27-43. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610709486444 [ Links ]

Raidt EH 1991. Afrikaans en sy Europese verlede. Kaapstad, Suid-Afrika: Nasionale Opvoedkundige Uitgewery Beperk. [ Links ]

Reach Out & Read 2015. Importance of reading aloud. Available at https://www.reachoutandread.org/why-we-matter/child-development/. Accessed 21 November 2018. [ Links ]

Reid G 2007. Motivating learners in the classroom: Ideas and strategies. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996a. Act No. 84, 1996: South African Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 377(17579), November 15. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996b. National Education Policy Act, 1996. Government Gazette, 370(17118), April 24. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996c. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Robertson J 2017. Do as I do, read as I read: The role of the adult in creating confident readers. In R Evans, I Joubert & C Meier (eds). Introducing children's literature: A guide to the South African classroom. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Scheffel DL, Shroyer J & Strongin D 2003. Significant reading improvement among underachieving adolescents using LANGUAGE! A structured approach. Reading Improvement, 40(2):83-97. [ Links ]

Schleicher A & Tang Q 2015. Editorial - Education post-2015: Knowledge and skills transform lives and societies. In EA Hanushek & L Woessmann (eds). Universal basic skills: What countries stand to gain. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264234833-2-en [ Links ]

Singh MKM, David AR & Choo JCS 2012. Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) as an independent learning tool at an institution of higher learning. Ubiquitous Learning: An International Journal, 4(1):77-89. [ Links ]

Snow CE, Barnes WS, Chandler J, Goodman IF & Hemphill L 1991. Unfulfilled expectations: Home and school influences on literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/104159/harvard.9780674864481 [ Links ]

Spaull N, Pretorius E & Mohohlwane N 2018. Investigating the comprehension iceberg: Developing empirical benchmarks for early grade reading in agglutinating African languages (RESEP Working Paper Series No. WP01/2018). Matieland, South Africa: Research on SocioEconomic Policy (RESEP); Department of Economics. Available at https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Spaull-etal-WP-v11-ESRC-Paper-1-Comprehension-iceberg-v4.pdf. Accessed 25 February 2020. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa, Republic of South Africa 2018. Mid-year population estimates 2018 [Media release]. 23 July. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=11341. Accessed 13 November 2018. [ Links ]

Steyn HJ, Wolhuter CC, Vos D & De Beer ZL 2017. Die Suid-Afrikaanse onderwysstelsel: Kernkenmerke in fokus. Noordbrug, Suid-Afrika: Keurkopie. [ Links ]

Stipek D 2002. Motivation to learn: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Sweet AP & Guthrie JT 1996. How children's motivations relate to literacy development and instruction. The Reading Teacher, 49(8):660-662. [ Links ]

The Psychologist Notes Headquarters 2019. What is Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory? Available at https://www.psychologynoteshq.com/bronfenbrenner-ecological-theory/. Accessed 25 April 2020. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation 2006. Strong foundations: Early childhood care and education. Paris, France: Author. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147794. Accessed 11 June 2021. [ Links ]

Van Vuuren D 2007. Wie beinvloed jou kinders? Vrouekeur, 16 November. [ Links ]

Vos E, Nel C & Van den Berg R 2014. Assesseer leesbegripstoetse werklik leesbegrip? Journal for Language Teaching, 48(2):53-79. https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v48i2.3 [ Links ]

Wigfield A, Eccles JS, Yoon KS, Harold RD, Arbreton AJA, Freedman-Doan C & Blumenfeld PB 1997. Change in children's competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A 3-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3):451-469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451 [ Links ]