Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n3a1877

ARTICLES

A case study of two teacher learning communities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Free-Queen Bongiwe ZuluI; Tabitha Grace MukeredziII

ISchool of Education, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa zuluf1@ukzn.ac.za

IIDurban University of Technology, School of Education, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development, a South African policy, the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the Department of Higher Education (DHET) call for the formation of professional learning communities and envisage support for teachers and access to enhanced professional development opportunities at the local level. However, the formation and operation of professional learning communities in a South African context is still unclear. In this article we use the concept of professional learning communities to examine the extent to which 2 teacher learning communities operate as professional learning communities. We used interviews, observations, survey questionnaires and document analysis to generate data. The findings of the study reveal that the 2 teacher learning communities were initiated by the DBE and not by teachers. However, the size of 1 teacher learning community and the nature of its functioning seemed to adhere to the characteristics of a professional learning community while the other did not. The findings indicate that professional learning communities that operate in developing contexts might be functional when all the stakeholders play a meaningful role in supporting professional learning communities.

Keywords: basic education; professional learning communities; teacher learning communities; teacher professional learning communities

Introduction and Background

Globally, continuous professional development (CPD) models have begun to shift away from the traditional approaches that are now seen as "fragmented and offering short courses or workshops that do not put emphasis on content knowledge" (Taylor, 2002:5) towards collaborative learning in communities. This is evident from the empirical studies and the expanding literature on how teachers learn in a community of practice, particularly in teacher learning communities (TLCs), sometimes called professional learning communities (PLCs) (Brodie, 2016; Brodie & Sanni, 2014; Cereseto, 2015; Graven, 2002, Jita & Mokhele, 2014; Pirtle & Tobia, 2014). In the African region dominated by developing countries such as Namibia and Zimbabwe, TLCs took on a form of teachers' clusters to improve quality of education through sharing of resources, experience and expertise (Aipinge, 2007). However, the studies on PLCs and TLCs were mainly done in developed Western contexts. The findings of a study conducted in the Netherlands established that teachers who learnt collaboratively kept engaged in professional learning activities for longer periods and felt more confident at the start of innovation compared to those teachers who learnt mainly individually (Henze, Van Driel & Verloop, 2009:196). There is still a need for understanding the formation and operation of PLCs in developing contexts such as South Africa. In South Africa the DBE and the DHET noted that teachers were not accessing teacher development opportunities that were close to where they lived and worked. Consequently, the DBE and DHET then realised a need to promote teacher development through PLCs.

In response to the limited professional development opportunities, the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development (ISPFTED), a South African policy, was launched by the DBE and the DHET in 2011. The intention of the ISPFTED was to improve the quality of teacher education and development within a 15-year time-frame. The DBE and DHET (2011) envisaged that the establishment of PLCs in schools would enhance professional development at the local level, because teachers were experiencing significant difficulties in accessing and receiving support, resources and CPD opportunities close to where they lived and worked. This was especially true for the majority of teachers working in rural areas, whose difficulty in accessing professional development opportunities was even more pronounced. This article emerged from a larger research study conducted from 2012 to 2014 in the Zethembe (pseudonym) district, one of the 12 DBE districts in the KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa. The big study explored two TLCs: the commerce and the mathematics teacher learning communities focussing on how teachers learn, what they learn and the nature of collaborative relationships. The Zethembe district is in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal. The majority of schools in the district have limited resources and are organised into four circuits of approximately 20 high schools each. The Commerce Teachers' Association was formed in 2010. The commercial school subjects presented in the Zethembe district are accounting, business studies, economics, economics and management sciences. The Commerce Teachers' Association draws teachers from 87 high schools in the district. The Mathematics Group of 25 high school teachers form a circuit cluster that was formed in 2001. The Mathematics Group is supported by a non-governmental organisation (NGO) from outside of Zethembe District.

We used the concept of a PLC to explore the extent to which the two TLCs included here reflect the characteristics of effective PLCs. The research question of this study was: To what extent do the two identified teacher learning communities operate as professional learning communities? From the findings of this study, teachers, the DBE, the DHET, NGOs and all the stakeholders may gain insight into how these PLCs could be further supported and developed to transform them into effective PLCs, thereby enhancing teacher professional learning.

Literature Review and Conceptual Framework: Features of a Professional Learning Community (PLC)

International literature on PLCs (Hargreaves, Berry, Lai, Leung, Scott & Stobart, 2013; Pirtle & Tobia, 2014; William, 2007/2008) has established that empirical research on PLCs faces a problem in that there is a conceptual and empirical fog surrounding the PLC, and that the term is used interchangeably with TLC. When Hargreaves et al. (2013) argue that the term "PLC" has become over-used and that its meaning is often lost, they highlight that PLC is the name given to teachers' collaborative professional learning that focuses specifically on practice rather than on teaching and learning, while TLC embodies characteristics closely associated with sustained improvement in school teaching and learning. William (2007/2008) contends that TLCs are only those small groups of teachers who learn from and attempt to make changes in their classroom practice. He further states that TLCs do not include administrators and other professionals, although these people can provide TLCs with support and advocacy. Only when teachers reflect on their instructional practice, consider the effect that instruction has on students, and implement insights gained from the meeting or workshop to improve their teaching performance, can such collaboration be called a PLC (Pirtle & Tobia, 2014:1). Interestingly, in China, PLCs for teachers are specifically called teacher professional learning communities (TPLCs) and are defined as "environments in which teachers interact and collaborate regularly around issues of teaching and learning and engage in the production and consumption of knowledge about improved practices for student learning" (Sargent & Hannum, 2009:258). One may thus conclude that reflection and collaboration are central aspects of an effective PLC.

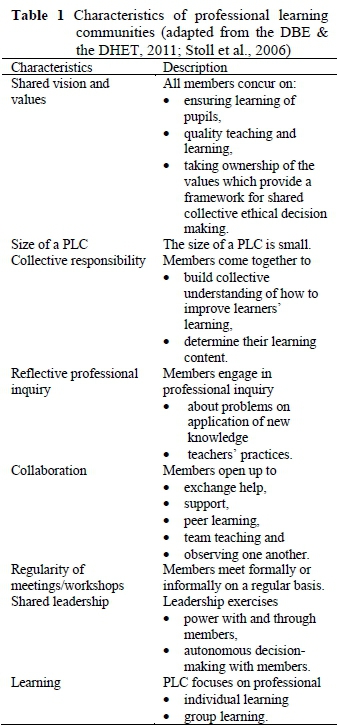

In the South African context, "PLCs are communities that provide the setting and necessary support for groups of classroom teachers, school managers and subject advisors to participate collectively in determining their own developmental trajectories, and to set up activities that will drive their development" (DBE & DHET, 2011:14). This definition of PLCs seems to imply that they operate within schools. Studies in the South African context have overwhelmingly focused on PLCs within schools. This is evident in Brodie's (2016) work, where different groups of South African researchers have studied PLCs within schools. Aligned with international literature (Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace & Thomas, 2006) the ISPFTED identifies several features of PLCs: shared values and vision, collective responsibility, reflective professional inquiry, collaboration, regular meetings and workshops, leadership, group and individual learning (see Table 1).

The essence of PLCs lies in a collaborative work culture and reflection. These two characteristics of PLCs make them different from traditional models of professional development such as once-off workshops at a central venue. Stoll et al. (2006) suggest that in order to enable PLCs to grow into collaborative learning and knowledge sharing communities, there should be adequate infrastructure for team learning opportunities. These are possibilities for members to play new roles, for example in curriculum leadership, and in creating and sharing stories of individual and community success (Chow, 2016; Hargreaves et al., 2013; Stoll et al., 2006).

Yet, based on the available literature and the ISPFTED it appears as if PLCs are poorly understood in terms of how they should be formed and how they should operate. Little seems to be known about PLCs outside of schools. In the South African context, the number of teachers in small rural schools is generally lower. In some instances, one finds that one teacher teaches one subject to all the grades, for example, one teacher teaching mathematics from Grade 8 to Grade 12. This situation implies that PLCs within one school might limit collaborative learning between teachers from different schools. Considering that PLCs and TLCs are distinct from one another, we use the term "TLC" because teachers' groups may not reflect all the features of a PLC. The aim of this article is to investigate the extent to which the two identified cases reflect the characteristics of a PLC. The PLC's characteristics in Table 1 were used as the conceptual framework for this research.

Methodology

An interpretive case study research design was used with the aim of exploring a general issue within a limited and focused setting (Rule & John, 2011). Purposive sampling was used to select two cases and eight participants. In the Commerce Teachers' Association, the sample consisted of four participants; three teachers and the subject advisor for economics. In the Mathematics Group, the sample consisted of the four participants who were interviewed (see Appendix A for the interview schedule), three teachers and the NGO mathematics facilitator. All the participants were given pseudonyms.

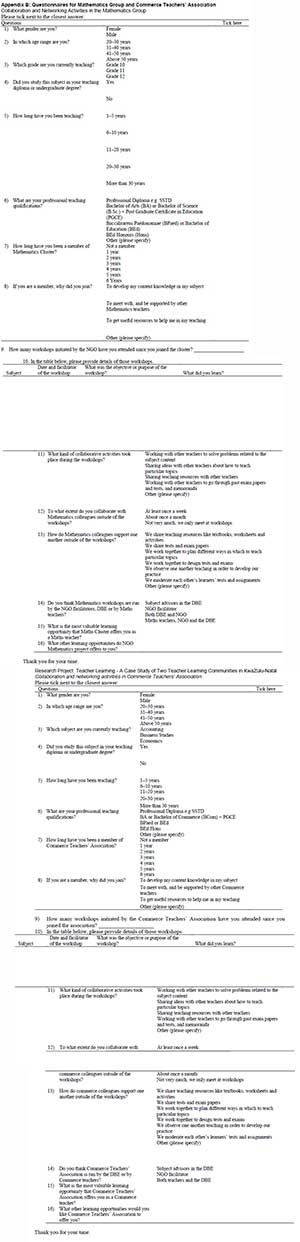

Data generation included three unstructured observations which were held in each TLC. The six observations were aimed at gauging the behaviour patterns of participants during their meetings and workshops (Nieuwenhuis, 2007). Detailed notes were taken during the meetings and workshops for each TLC and one workshop for the Mathematics Group was video-taped. Documents such as attendance registers, annual reports, and documents distributed at the workshops were analysed. In 2014, a survey questionnaire (see Appendix B) was used to gain perspectives of how teachers learnt in each group, the kind of knowledge learnt, and the nature of collaborative relationship in each of the two TLCs. According to Creswell (2014) the combination of quantitative and qualitative data generation suggests mixed methods. We argue that this study remained firmly in the qualitative approach because the survey questionnaires were not undertaken in order to cross check or confirm findings of the qualitative data, but mainly to reach many participants with open-ended questions seeking qualitative data. The questionnaire was also intended to generate participants' biographical data through closed-ended questions. In the Commerce Teachers' Association, the questionnaires were administered during a meeting which was held on 16 October 2014. We targeted at least 200 commerce teachers from 87 high schools in the Zethembe district. However, only 58 questionnaires were returned - a response rate of 30%. For the Mathematics Group we targeted 25 mathematics teachers from 20 high schools in a circuit. The questionnaires were administered in the last moderation meeting held on 22 October 2014. Twenty-five questionnaires were issued and 19 questionnaires were returned - a response rate of 75%.

Thematic analysis was adopted to analyse the transcribed qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and observations from audio and videotapes. Data from document analyses were also thematically analysed. The open-ended responses from the questionnaires were thematically analysed, while the closed-ended responses were analysed statistically. Additionally, the PLC features (Table 1) were used as an analytical tool to explore the extent to which the two TLCs operate as PLCs.

Permission to conduct this research was obtained from the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Basic Education. Ethical clearance was granted by the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Ethics Committee (College of Humanities). All the participants signed consent and we acknowledged their rights to withdraw or terminate participation.

Findings

This section is presented in two sections: the extent to which the Commerce Teachers' Association reflects the features of a PLC and the extent to which the Mathematics Group reflects the features of a PLC.

The Extent to which Commerce Teachers' Association Reflects the Characteristics of a PLC Formation and size of Commerce Teachers' Association

The Commerce Teachers' Association which was established in 2010, consisted of 287 commerce teachers (96 accounting, 106 business studies and 85 economics) and four subject advisors. In relation to the size of a PLC, William (2007/2008)

highlights that when the group is too large the meeting time may run out before all members can talk about what they have learnt. The findings of our study indicate different views by the participants about who initiated the Commerce Teachers' Association. The chairperson Celokuhle and the general secretary Sebenzile stated that the association was initiated by the teachers themselves. However, 28 of the 58 teachers surveyed stated that the Commerce Teachers' Association was arranged by commerce teachers and DBE officials. Eight teachers stated that the subject advisors arranged the Commerce Teachers' Association. The economics subject advisor concurred with what Sibusisiwe said:

Mostly it is our subject advisors and we have got commerce educators, those are the members. The subject advisors invited us to join the group and they made us aware of the Commerce Teachers' Association and invited us to attend a workshop for the Commerce Teachers' Association. (interview held on 27/08/2013)

While international literature (Hargreaves et al., 2013) claims that PLCs are initiated by teachers themselves, the formation of the Commerce Teachers' Association seemed to have been in line with managerial orders from the DBE authorities as reflected in the above interview extract. In this case, the Commerce Teachers' Association was likely to last only as long as the instruction lasted.

Shared vision

As for the shared vision, the four participants who were interviewed highlighted that the Commerce Teachers' Association was formed to improve learner performance in accounting, business studies and economics. The economics subject advisor illustrated the purpose: "The main idea is to improve results. We network with other subject advisors from other districts who already had this association" (interview held on 20/07/2014).

Contrary to the PLC feature on the shared vision, this interview extract suggests that the Commerce Teachers' Association shared the DBE-mandated vision to improve learners' performance. Generally, the poor performance of learners in the National Senior Certificate (NSC) was a major concern in the Zethembe district. According to the District Analysis Report of the 2009 National Senior Certificate Results, the overall pass rate in Grade 12 was 45.13%, which placed the district 11th out of 12 districts in KwaZulu-Natal.

Regularity of meeting

The findings from the questionnaires show that commerce teachers were not meeting regularly. The findings seem to suggest that approximately 40% of commerce teachers were not collaborating outside of the workshops of Commerce Teachers' Association, which might be because it is seen as only a DBE initiative. This is depicted in Table 2.

In addition to the commerce teachers' responses, the economics subject advisor's response on the question on frequency of meetings was: "We are supposed to meet once per term. We have not met this year due to other programmes ..." (interview held on 20/07/2014).

This situation is in contrast with the PLC feature of regular meetings. The attendance registers of workshops were called Matric Intervention Programmes (MIPs) because the focus of these meetings was on Grade 12 content. MIPs are normally used by the DBE to refer to its Grade 12 intervention programmes. These workshops were held at a central venue.

Collective responsibility

The findings from the interviews show that the Commerce Teachers' Association was led by the executive committee elected by the teachers, and the subject advisors were ex-officio members. Collective decision-making was evident during the election of a new executive committee where teachers nominated the new executive committee. The meeting was held on 16 October 2014. However, the DBE made the decisions. This was evident from the circular that was read by the Deputy Chief Education Specialist: "As Commerce Teachers' Association is a non-profit organization, the affiliation fee per school is R200 per year, payable on the day of the elective meeting" (Election meeting observation: 16/10/2014).

While Priestley, Miller, Barrett and Wallace (2011) highlight the importance of teachers' political participation in the decision-making process, this circular extract suggests that decisions were delegated by the DBE.

Collaboration

The findings from the survey questionnaires depicted in Table 3a and 3b show that there was collaboration within the Commerce Teachers' Association. Teachers were allowed to choose more than one answer, thus the percentage in these two tables adds to more than 100%. The findings shown in Table 3a suggest that the commerce teachers collaborated during the workshops:

However, these findings from the questionnaires seem to be contrary to the events of the economics workshop observed on 27 August 2013. During the workshop only the facilitator interacted with the teachers through questions. In the following observation extract the facilitator used questions to show teachers how to introduce a topic:

Mr Khambule: What is price elasticity? Yes, price elasticity is Grade 11 work, so start by exposing learners to responsiveness of price to demand before introducing the markets. What type of the market does the graph represent? All the teachers: Perfect market.

Mr Khambule: Yes, perfect market. Teachers, learners need to know how to identify and they cannot identify if they do not know the graphs of different market structures. Let us move to the next question.

Teacher: The price is determined by the interaction of demand and supply.

Mr Khambule: Thank you. It is very important to explain to the learners the difference....

The extract shows the interaction with questions between the facilitator and the teachers. In line with the cognitive perspective the teachers were learning how to introduce the topic using a question and this knowledge was then expected to be transferred to their classroom situations.

Leadership

The findings indicate that the DBE authorities seemed to be leading the Commerce Teachers' Association by calling meetings, choosing facilitators and co-ordinating workshops. This situation is evident from the following observation extract where the economics subject advisor coordinated the economics revision workshop: "Teachers must sign the attendance register, participate fully, cell phones must be on silent mode, [and they are expected to] behave as responsible adults" (observation: 23/09/2013).

This extract indicates how the DBE official played a leading role during the workshop. The workshop was facilitated by the external facilitator chosen by the economics subject advisor.

Learning

Although the data from the questionnaires show that the Commerce Teachers' Association seemed to collaborate during and outside of the workshops, findings from the observations suggest that individual learning, which is underpinned by a cognitive perspective, was promoted. This was evident from the external facilitator's introductory remarks: "How do we make learners pass, Colleagues? The language that we are going to use today will be graphical representations, cartoons, data and sets of questions that a learner must know" (facilitator: 23/09/2013).

This observation extract shows the focus of learning in the Commerce Teachers' Association facilitated by the external facilitator. Teachers learnt strategies of how to do revision with Grade 12 learners and were expected to transfer the revision skills and revision questions to their Grade 12 classes. The findings from the interviews indicate that the Commerce Teachers' Association was constrained by the unavailability of resources and funding to support the association. In the following extract the general secretary refers to the issue of membership fees: "The funding of this organisation is from its members, which are us teachers, so colleagues, let us pay our membership fee. Money is needed for petrol, accommodation and the gift for the facilitator" (Sebenzile: 23/09/2013).

From this quote it is clear that the association depends on the membership fees from each teacher to cover the expenses of the external facilitators. However, it does not mean that the shortage of collaborative learning is due to the shortage of funding, because collaboration can be informal.

The Extent to which the Mathematics Group Reflects the Characteristics of a PLC

Formation and the size of the mathematics group

The Mathematics Group is part of the DBE cluster which is assisted by an NGO. The NGO became involved with the group in 2007 to help mathematics teachers to master content and to make them competent in the teaching of mathematics, especially in rural schools faced with a shortage of resources. The cluster consisted of approximately 25 teachers. However, only 14 teachers were active in the Mathematics Group workshops. The 14 teachers were from 10 high schools; eight high schools represented by one teacher each and three high schools represented by two teachers each.

Shared vision

The Mathematics Group is a teachers' cluster functioning as "an administrative organ of the DBE that helps to simplify the management of schools" (Jita & Ndlalane, 2009:58). However, the 14 mathematics teachers active in the workshops shared a vision that seemed to focus on learning more than the DBE mandates: "One of the challenges that they are trying to address in our Maths Group is to help maths teachers to master the maths concepts as well as how to use technology to teach mathematics" (Jabulani: 1/10/2013).

This excerpt suggests that the 14 mathematics teachers' shared vision was based on the construction of new knowledge in order to improve the teaching and learning of mathematics.

Regularity of meeting

The findings suggest that the Mathematics Group's met in different places on a regular basis. The mathematics teachers attended content-based workshops which were facilitated by the subject advisor (Table 4 shows attendance figures), the NGO facilitator and the teachers themselves.

Regarding the workshops, co-operation between the DBE and the NGO facilitator was evident. The NGO facilitator explained the DBE's arrangements to accommodate her (Siza): "I used to come every 2 weeks according to DBE time which is 12h00 onwards. The DBE said 'would you rather go for 2 whole days every term?" (Siza: 22/11/2014).

Additionally, the NGO facilitator also highlighted that the Mathematics Group attended workshops during school holidays at the NGO.

Leadership

The findings suggest that the leadership in the Mathematics Group functioned consistently with shared leadership, collective responsibility and autonomous collective decision-making. For example, the cluster coordinator responded to the question about who decided on what was learnt during the workshop:

... normally the facilitator decides on what the topic for the day is, but she is flexible, which means it can change with the teachers if there is a need to do anything just for today; she was only prepared for the cyclic geometry but we saw the need to do the last term papers for Grade 12. (Hlengiwe: 21/5/2013)

The NGO facilitator exercised power through and with the teachers in the decision-making. In line with Butler, Schnellert and MacNeil (2015), this situation seems to confirm that the teachers were independent in making decisions about what should be learnt, which was evident when the NGO facilitator changed her programme in order to accommodate the teachers' learning needs.

Collaboration

From the questionnaire findings, 40% of the 19 mathematics teachers collaborated during the workshops and outside of the workshops at least once a week. The collaboration was in different ways like sharing teaching resources such as textbooks, worksheets and activities; sharing tests and examination papers; working together to plan different ways in which to teach particular topics; working together to design tests and examinations; observing one another teaching in order to develop practice; and moderating each other's learner tests and assignments. Bongani explained about team teaching during the interview, which they did willingly without the involvement of the NGO facilitator and subject advisor: "We divide topics amongst ourselves. We would then take turns when teaching the same learners. We do not just do it to the members of the small group we formed but with other schools of other teachers" (Bongani: 2/10/2013).

Hargreaves et al. (2013) maintain that observing peers teaching is a core PLC practice because it supports the de-privatisation of practice, fosters accountability among participants and focuses directly on classroom teaching and learning.

However, a quarter of the 19 teachers responded saying that their collaboration was not significant as they only met at workshops. Ten per cent of the teachers indicated that they did not meet at all outside of the workshops. This is contrary to the frequency expected for PLC characteristics.

Learning

The findings suggest individual and group learning was evident in the Mathematics Group. The individual learning is depicted in the following observation extract on solving triangles in trigonometry:

Siza: You must show the kids the six steps. STEP 1: Write an 'r' on all the line segments equal to the radius and fill in all the angles in terms of x. STEP 2: Use the sine rule in ∆ROQ to find 'RQ in terms of r andx' ... You must also do the same thing with the kids; the kids must first analyse the diagram. Now, could you try that one? - You have a space below.

Pair/small groups discussed how to teach learners using new material provided by the NGO facilitator. This is shown on the following observation extract:

5. The daily production of a sweet factory consists of at most 100 g of chocolate-covered nuts and at most 125 g of chocolate-covered raisins which are then sold in two different mixtures. Mixture A consists of equal amounts of nuts and raisins and is sold at a profit of R5 per kg. Mixture B consists of 1/3 nuts and 2/3 raisins and is sold at a profit of R4 per kg. Let there be x kg of mixture A and y kg of mixture B.

5.1 Write down the constraints represented by the above system.

5.2 Write down the equation of the profit function.

5.3 Represent the above graphically on the attached diagram sheet. Clearly indicate the feasible region.

Siza: Who will show us how to do this one? If somebody wants to do it....

Hlengiwe (coordinator): I suggest that we do it together.

Siza: The white board at the back can be used. Teacher 2 (male): The mixture B is a problem for the learners, let's start with 5.1. This is how I normally do it. If you picture it like this it will be easy for the learners:

Hlengiwe: The way I understood it, it should be half per kg and half per kg is connected with the given information.

Jabulani: Hlengiwe, elaborate please. Hlengiwe: I emphasise the point of half-half. Teacher 2: Guys, lets us come up with constraints and form the equation.

Teacher 1: At most it is represented by 1/2x +1/3y.

The above extract appears as a collective comprehension task in which teachers solve a problem as a whole group (Patchen & Smithenry, 2014:608). This kind of teacher learning is consistent with collective responsibility. The findings suggest that another form of learning was achieved through leadership development (Chow, 2016) which may be referred to as "train-the-trainer. " This is evident from another NGO programme known as the Laptop project, which is facilitated by five lead teachers within the group who were first trained to teach mathematics using the technology supplied by the NGO facilitator. The lead teachers were then required to train other mathematics teachers. Jabulani commented about the Laptop Project during the interview: "There is Mathematics software called a Geometal Sketch Pad. I have learnt how to use the Geometal Sketch Pad in the classroom" (Jabulani, 1/10/2013).

According to Chow (2016), this shared leadership in the Mathematics Group creates growth and empowerment. The findings suggest that learning for the 14 teachers in the Mathematics Group focused on the construction of knowledge individually and collaboratively and the NGO facilitator provided opportunities for negotiation between teachers. Individual learning and group learning in PLCs benefits teachers to gain different types of teacher knowledge (Zulu, 2017).

Reflective inquiry

The findings from the observation of the content workshop indicate mathematics teachers' reflections on the examination paper. One of the teachers commented during the workshop: "Though the memorandum came out, the memorandum was showing the steps" (Teacher 2).

In this quote, the teacher was reflecting about one of the challenges that she encountered when she was marking the mathematics examination -that they did not understand the content in the marking memorandum. In line with Stoll and Louis (2007), reflective inquiry means that teachers have a thorough conversation about their teaching and learning. The 14 mathematics teachers seemed to have had a thorough conversation about what their learners found difficult, such as: "The mixture B is a problem for the learners" (Teacher 2).

Clearly, the findings from this section reveal that the Mathematics Group reflected many of the characteristics of a PLC in terms of size (14) while the Commerce Teachers' Association (241) did not.

Discussion

Surprisingly, the Commerce Teachers' Association was purposefully selected as the group that was reportedly initiated by commerce teachers themselves, but the learning activities that were observed in the Commerce Teachers' Association seemed to have been managerially driven. Thus, the Commerce Teachers' Association showed limited activities that would lend themselves to standardisation such as assessment, reporting practices, interventions protocols and pedagogical best practices (Servage, 2009). The Mathematics Group was initiated by the DBE as a subject cluster, and so one could have expected more contrived collegiality and mandated collaboration, yet the learning situation in the Mathematics Group seemed to be in contrast with international literature which states that in mandated collaboration, teachers are expected to further the science of teaching (Servage, 2009).

Learning in the Commerce Teachers' Association was once off, whereas learning in the Mathematics Group was continuous and seemed to be sustained by the involvement of the NGO facilitator in terms of the funding, resource provision and regularity of workshops. Chow (2016) highlights that in order to enable the PLCs to grow into collaborative learning and knowledge sharing communities, there should be adequate infrastructure. The findings indicate that the NGO facilitator was demonstrating how to teach certain topics such as how to use the sine rule, to master the topics in order to improve teaching and learning of mathematics, created collaborative learning during the workshops. This leadership role of the NGO facilitator seemed to be a "powerful lever" (Priestley et al., 2011:269) in developing innovation in the Mathematics Group because she assumes a collegial figure rather than an authoritarian one. The findings of the study further suggest that learning in the Mathematics Group was also achieved through leadership development (Chow, 2016). This is evident from another NGO programme known as the Laptop project programme. Furthermore, the Mathematics Group's relational dimensions appeared to be based on sharing their ideas, experiences and challenges in order to support each other. This situation is in line with reflective professional inquiry, which includes "dialogue of serious education issues" (Stoll & Louis, 2007:2).

Contrary to the literature which states that PLCs have facilitators who are servant leaders who highlight the value of members' contributions, and guide teachers into a state of interdependency and reciprocity (Calhoun & Green, 2015:60), the role of the DBE officials seemed to suggest that the DBE took charge of the Commerce Teachers' Association rather than being steered by the teachers themselves. International studies on PLCs established that collective responsibility helps to sustain commitment, create accountability for those members who do not do their fair share, and ease isolation (Stoll et al., 2006; William, 2007/2008).

In contrast to this statement, the findings suggest that the lack of collective responsibility may have resulted in the low levels of collaboration among teachers during workshops. Some teachers did not see the need to contribute during the workshops because the subject advisors were regarded as the "experts." The findings suggest that leadership in the Commerce Teachers' Association appeared as a paternalistic leadership underpinned by a high level of accountability about Grade 12 learners' performance. This kind of leadership is a barrier to autonomy in PLCs' decision-making (Chow, 2016:299).

Conclusion

In this study we found that subject clusters can operate as PLCs where teachers can share their personal professional practices other than meeting for moderation and curriculum reforms, and the matric intervention programmes facilitated by the DBE. These findings support the findings of another study conducted in Mpumalanga, which showed that subject cluster meetings outside of schools provided teachers with opportunities to enhance their content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge (Jita & Mokhele, 2014). It is likely that the Mathematics Groups reflected the characteristics of a PLC better, due to the small size of the group and the presence of the NGO facilitator. The NGO facilitator created a conducive environment for sharing among the mathematics teachers and these teachers apparently took ownership of their own learning and development trajectories. On this basis it could be recommended that the Commerce Teachers' Association and similarly sized groups could break into smaller groups to enable teachers to decide on what they wanted to learn. It appeared that it was difficult for teachers to propose divergent ideas in the workshops where their authorities (subject advisors) were in the dominant position. Although the findings of this study cannot be generalised, the two TLCs have shown how leadership can support or impede the PLCs. Subject advisors can nurture PLCs by promoting shared values and encouraging teachers to take ownership of their groups.

In this study we explored the nature of the functioning of the two TLCs in order to provide insight into what teacher PLCs really are in practice. We further highlighted factors that might help to transform existing subject groups into PLCs. Therefore, the DBE needs to promote greater understanding of what PLCs are and needs to allow time for teachers to engage in PLCs -especially teachers in rural schools where professional learning opportunities tend to be limited. However, this was a small study in which we investigated only two learning communities. More comprehensive research involving a bigger sample may provide better insights into teacher professional learning through these subject groups. The research could then be extended to investigate how their learning influences the teachers' practices.

Authors' Contribution

This article was taken from the first author's Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) research study. The second author was one of the supervisors. The first author wrote the manuscript and it was reviewed by the second author.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 1 May 2019; Revised: 8 April 2020; Accepted: 19 May 2020; Published: 31 August 2021.

References

Aipinge LP 2007. Cluster centre principals' perceptions of the implementation of the School Cluster System in Namibia. MEd thesis. Grahamstown, South Africa: Rhodes University. Available at http://vital.seals.ac.za:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/vital:1449?site_name=GlobalView. Accessed 19 August 2021. [ Links ]

Brodie K 2016. Facilitating professional learning communities in mathematics. In K Brodie & H Borko (eds). Professional learning communities in South African schools and teacher education programmes. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Press. [ Links ]

Brodie K & Sanni R 2014. 'We won't know it since we don't teach it': Interactions between teachers' knowledge and practice. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 18(2):188-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10288457.2014.930980 [ Links ]

Butler DL, Schnellert L & MacNeil K 2015. Collaborative inquiry and distributed agency in educational change: A case study of a multi-level community of inquiry. Journal of Educational Change, 16:1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-014-9227-z [ Links ]

Calhoun DW & Green LS 2015. Utilizing online learning communities in student affairs [Special issue]. New Directions for Student Services, 2015(149):55-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20117 [ Links ]

Cereseto A 2015. What and how do teachers learn in professional learning communities? A South African case study. PhD thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/19707. Accessed 19 August 2021. [ Links ]

Chow AWK 2016. Teacher learning communities: The landscape of subject leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(2):287-307. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2014-0105 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education & Department of Higher Education and Training 2011. Integrated strategic planning framework for teacher education and development in South Africa 2011-2015. Pretoria, South Africa: Authors. Available at http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/Intergrated%20Strategic%20Planning%20Framework%20for%20Teacher%20Education%20and%20Development%20In%20Sou1h%20Af

rica,%2012%

20April%202011.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2021. [ Links ]

Graven MH 2002. Mathematics teacher learning, communities of practice and the centrality of confidence. PhD thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mellony-Graven/publication/276282964_MATHEMATICS_TEACHER_LEARNING_COMMUNITIES_OF_PRACTICE_AND_THE_CENTRALITY_OF_CONFIDENCE/links/5555bb2d08aeaaff3bf492c0/MATHEMATICS-TEACHER-LEARNING-COMMUNITIES-OF-PRACTICE-AND-THE-CENTRALITY-OF-CONFIDENCE.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2021. [ Links ]

Hargreaves E, Berry R, Lai YC, Leung P, Scott D & Stobart G 2013. Teachers' experiences of autonomy in continuing professional development: Teacher learning communities in London and Hong Kong. Teacher Development, 17(1):19-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.748686 [ Links ]

Henze I, Van Driel JH & Verloop N 2009. Experienced science teachers' learning in the context of educational innovation. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(2): 184-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108329275 [ Links ]

Jita LC & Mokhele ML 2014. When teacher clusters work: Selected experiences of South African teachers within the cluster approach to professional development. South African Journal of Education, 34(2):Art. # 790, 15 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071132 [ Links ]

Jita LC & Ndlalane TC 2009. Teacher clusters in South Africa: Opportunities and constraints for teacher development and change. Perspectives in Education, 27(1):58-68. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J 2007. Qualitative research designs and data gathering techniques. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Patchen T & Smithenry DW 2014. Diversifying instructions and shifting authority: A cultural historical theory (CHAT) analysis of classroom participant structures. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(5):606-634. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21140 [ Links ]

Pirtle SS & Tobia E 2014. Implementing effective professional learning communities. SEDL Insights, 2(3):1-8. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED593422.pdf. Accessed 19 November 2018. [ Links ]

Priestley M, Miller K, Barrett L & Wallace C 2011. Teacher learning communities and educational change in Scotland: The Highland experience. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2):265-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903540698 [ Links ]

Rule P & John V 2011. Your guide to case study research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Sargent TC & Hannum E 2009. Doing more with less: Teacher professional learning communities in resourced constrained primary schools in rural China. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(3):258-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109337279 [ Links ]

Servage L 2009. Who is the "professional" in a professional learning community? An exploration of teacher professionalism in collaborative professional development settings. Canadian Journal of Education, 32(1):149-171. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/canajeducrevucan.32.1.149.pdf?casa_token=7_ge6NxADTIAAAAA:2F6fZLwQExHECgLsJ-Kyu5rOIVZCYPeKbf36ViTqQA4lgG4S0CEDFjD0qWlDzVoHJPXVeHst3cpdecMVEyD4gwDH-SOao_v_WfLRKcuXK-fo1qZgsJZt0Q. Accessed 18 August 2021. [ Links ]

Stoll L, Bolam R, McMahon A, Wallace M & Thomas S 2006. Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Education Change, 7:221-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8 [ Links ]

Stoll L & Louis KS (eds.) 2007. Professional learning communities: Divergence, depth and dilemmas. New York, NY: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor N 2002. Accountability and support: Improving public schooling in South Africa. A systemic framework. Paper presented to the National Consultation on School Development, Department of Education, Pretoria, South Africa, 29 January. Available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.565.8794&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 21 August 2021. [ Links ]

William D 2007/2008. Changing classroom practice. Educational Leadership, 65(4):36-12. [ Links ]

Zulu B 2017. Teacher learning: A case study of two teacher learning communities in KwaZulu-Natal. PhD thesis. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/15581/Zulu_Bongiwe_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y . Accessed 18 August 2021. [ Links ]

Appendix A: Interview Schedule

INTERVIEW SCHEDULE

Title: TEACHER LEARNING IN COMMERCE TEACHERS' ASSOCIATION: A CASE STUDY OF TWO TEACHER LEARNING COMMUNITIES IN KWAZULU-NATAL

Thank you so much for being available for an interview. You have signed a consent form, so you are aware that this project is part of my studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). Everything that you say will be kept confidential. The interview should take 60 minutes.

A: BIOGRAPHIC QUESTIONS

1) How old are you?

2) How long have you been teaching?

3) What subject(s) and grades are you teaching and how long have you been teaching this/these subject(s)?

4) Were you trained to teach these subjects?

B: FORMATION AND MEMBERSHIP OF TEACHER LEARNING COMMUNITY

5) Do you belong to any teacher learning community? If yes tell me its name and when it was formed?

6) Who initiated the formation of this teacher learning community and why was it formed?

7) Who are the members of this teacher learning community? How were these members invited to join the group?

8) What is your portfolio in your teacher learning community?

9) When do you meet?

10) What sustain the functioning of this teacher learning community in terms of resources and funding?

C: TEACHER LEARNING AND KNOWLEDGE CONSTRUCTION

11) What do you understand by the term teacher learning?

12) Is there a learning that takes place in this learning community? If yes how does it happen? What are you learning? What are the activities that teachers do if there are any? Who facilitate this learning?

13) How useful or not useful is the learning that takes place in your teacher learning to your teaching practice? (Why?)

14) Who pre-determined what should be learnt in your teacher learning community?

15) Describe other learning experience that you have experience in your teacher learning community. Who pre-determined it? Who facilitated it? What were the activities? What was the focus? What were the resources that were used and who provided them?

D: NATURE OF COLLABORATIVE RELATIONSHIP IN THE TEACHER LEARNING COMMUNITY

16) How do you describe the relationship between teachers in this teacher learning community?

17) Who is leading the teacher learning community how was she/he chosen?

18) How do you feel about yourself regarding learning in your learning community? Does it improve the sense of being a professional? (Explain)

19) What does it mean for you to say that your teacher learning community is a professional learning community?

Thank you