Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.41 no.2 Pretoria Mai. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n2a2010

ARTICLES

Exploring the pre-service teacher mentoring context: The construction of self-regulated professionalism short courses

Tanya Smit; Pieter H du Toit

Department of Humanities Education, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. tanya.smit@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

During work integrated learning (WIL), pre-service mentoring helps prepare final-year education students for the workplace. The pre-service teacher is placed alongside a mentor teacher, and the higher education institution (HEI) stipulates the timeline and the requirements. This study follows a wide-ranging research project, identified by the acronym FIRE (Fourth-year Initiative for Research in Education). In this article we focus on pre-service teacher mentoring experiences, partnerships, roles, and teacher identity development concerning mentor teachers, not mentor lecturers. The results of 2 baseline exploratory research surveys are shared. The attitudes, beliefs, opinions and practices of Senior, Further Education and Training phase mentor teachers and pre-service teachers were gathered, measured and compared. The responses to 2 cross-sectional questionnaires in electronic format provided a competence-base for the design of curricula for 2 short courses about mentoring and self-regulated professionalism. The 2 short courses were created for mentor teachers and pre-service teachers.

Keywords: mentor teachers; mentoring; pre-service teacher mentoring; self-regulated professionalism; short course curriculum development; work integrated learning

Introduction

Mentor teachers mentoring final-year students denoted as pre-service teachers is a well-known practice in teacher education contexts (Ambrosetti & Dekkers, 2010). The WIL pre-service training phase, during which pre-service teachers visit identified schools, is fundamental in preparing them for the practice of teaching (Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 2011). Ehrich, Hansford and Ehrich (2011:530) researched mentoring across the fields of education, business and medicine and conclude that "poor mentoring is worse than no mentoring." As part of the study being reported on, two separate quantitative cross-sectional electronic baseline surveys were distributed to mentor teachers and their pre-service teachers working in 50 schools around Pretoria, in the Gauteng province, South Africa. The justification was to build on existing international evidence in the pre-service mentoring context and provide specific data relating to the South African context. The rationale for the study can be clarified as a process of zooming in on pre-service teacher mentoring to construct curricula for two short courses that would promote self-regulated professionalism. The impetus was to professionalise WIL as a marriage between schools responsible for mentoring pre-service teachers and the Faculty of Education at the University of Pretoria.

Literature Review

WIL in the South African context

Pre-service teacher education is a talking point globally (Ambrosetti, 2014) and definitely in South Africa. In South Africa, the preparation of education students resides with teacher training institutions or universities. Teacher education programmes offered by universities include a four-year Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) degree. During WIL, pre-service teachers visit schools to observe and present several lessons as negotiated with the mentor teachers, who also mentor the students. Ambrosetti, Knight and Dekkers (2014) define a pre-service teacher as an education student who is not yet qualified to teach. In the context of this study we consider pre-service teachers to be students in their final year of study at a university.

The programmes for teacher preparation in South Africa have undergone "frequent transformation and change since the early nineties" (Fraser, 2018:1). Regional teacher training colleges and universities merged (Jansen, 2002) and the requirements for teacher education qualifications (Department of Higher Education and Training [DHET], Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2015) were standardised. According to Du Plessis and Marais (2013), the WIL period influences the preparation of pre-service teachers for the teaching profession. Together with the mentor teachers, university lecturers are responsible for mentoring and assessing pre-service teachers during the WIL period.

The current increase in student-teacher numbers at universities results in many students having to complete WIL (Fraser, 2018) at schools. Fraser (2018:1) states that "managers and mentor lecturers seek alternative models and strategies to cope." In our view, the mentor teachers at schools with which pre-service teachers engage in WIL activities are equally affected by the larger numbers of students who need to be accommodated.

In the Revised policy on the minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications, WIL is defined as "structured, supervised, integrated into the learning programme, spread across the learning programme, and it must be formally assessed" (DHET, RSA, 2015:15). In 2007, the European Commission criticised teacher education as failing to prepare students for the authentic workplace environment (Ioannidou-Koutselini & Patsalidou, 2015). Pre-service teachers are currently being prepared for the workplace by using the standard benchmark of "monitoring and supervision" (Fraser, 2018:1) with very few mentoring or self-regulated learning opportunities.

Pre-service teacher mentoring

Bozeman and Feeney (2007) claim that the beginning of mentoring research originates from Kram's (1983) article as cited frequently in this field. According to Crow (2012), there is no broad definition of mentoring. In 2007, "more than 50 definitions of mentoring existed in research literature" (Dawson, 2014:137). It is agreed to be a wide-ranging, multifaceted and disputed construct by researchers such as Crisp and Cruz (2009) and Kemmis, Heikkinen, Fransson, Aspfors and Edwards-Groves (2014). Brondyk and Searby (2013:197) make the following statement: "There are several factors that might explain this lack of empirically substantiated mentoring best practices in education. Mentoring is in the theory-building phase, where researchers are beginning to describe what it is in the field. "

Mentoring is used differently in different situations and for various purposes (Kemmis et al., 2014). We are troubled by the idea that "everyone thinks they know what it is and have an intuitive belief that it works" (Allen & Eby, 2007:7). From a constructivist frame of mind, we dispute that mentoring in the field of education always succeeds. This notion is underscored by Burghes, Howson, Marenbon, O'Leary and Woodhead (2009) who mention that an established 30 to 50% of educators in England leave the profession within the first 5 years. Schunk and Mullen (2013:362) reason that "research has shown mentoring to be effective, but not explained why."

Mentoring in educational contexts is expanding (Fletcher & Mullen, 2012). There are various approaches and models of mentoring, encountering varied requests (Clutterbuck & Megginson, 1999). Pre-service teacher mentoring is a complicated "triad alliance" (Fraser, 2018:1) between the mentor lecturer, mentor teacher, and the pre-service teacher. Ambrosetti (2014) declares European mentoring as non-directive and concentrating on mutuality and reciprocity. American mentoring is directive and focuses on sponsorship, networking or career outcomes. We agree with Geber and Nyanjom (2009) that these Western perceptions of mentoring may not be appropriate in the African context. The notion of the spirit of Ubuntu and part of the South African culture, including human virtues such as compassion and cooperation, are mentioned in the Constitution of the RSA, 1996 Our view is that mentoring practices might differ to some extent in different situations, countries and cultures. Clutterbuck and Megginson (1999) emphasise that various ethnic groups, genders, convictions, stages of development and status should be taken into account during mentoring. Therefore, the uniqueness of pre-service mentoring in South Africa is further explored in this baseline study.

Pre-service teacher mentoring models, partnerships, benefits and challenges

When a final-year education student is placed with a mentor teacher in a classroom, the pre-service teacher is not familiar with the specific school or classroom culture. We agree with Ambrosetti and Dekkers (2010) that unless the roles of the mentor teacher and the pre-service teacher are clearly defined, mentoring relationships will continue to function only according to predetermined opinions. In terms of mentoring models, Butler and Cuenca (2012) describe a mentor teacher as either a person playing the role of a coach, support, or network mediator. Buell (2004:63) outlines the following three models of mentoring: "Cloning, nurturing and friendship." Mentor teachers, among other things, base their conceptualisation of mentoring on their experiences as students (Butler & Cuenca, 2012). Still, in a 21st-century setting, we regard this viewpoint for the preparation of pre-service teachers as problematic.

The partnering of a mentor and a pre-service teacher is imperative in the mentoring context of final-year education students, as is the partnership that exists between institutions of higher education, schools and mentor teachers. Communication between the role players and a shared vision are vital (Herrera, Kauh, Cooney, Grossman & McMaken, 2008).

According to Ambrosetti et al. (2014), pre-service teachers have mentoring experiences that range from positive to harmful. Ehrich et al. (2011:8) conducted a literature study of various education articles dealing with mentoring and found that 82% of the studies reviewed describe mentoring as a productive process. Hudson (2013) states that mentoring can be advantageous to pre-service teachers, mentor teachers, schools and HEIs across the board. There are, however, various challenges or barriers in the authentic pre-service teacher mentoring situation. In The dark side of mentoring, Long (1997) mentions that funding for mentoring is usually insufficient or has been terminated, and the alliances between schools and universities are found tricky (Lynch & Smith, 2012). For a mentor teacher, the additional work required by mentoring can be regarded as an additional obligation, stressful and, time-consuming (Walkington, 2005). Pre-service teachers still feel insecure about their position and tasks in the mentoring relationship, and mentor teachers are not always confident in their mentoring abilities (Ambrosetti, 2012).

According to Ambrosetti et al. (2014:234), prospective teachers go through the following phases during mentoring and before entering the profession: "The preparation for mentoring, pre-mentoring towards mentoring and post-mentoring." There is a correlation between the work of Ambrosetti et al. (2014) and that of Stroot, Faucette and Schwager (1993) 20 years earlier. While comparing the phases identified by Ambrosetti (2014) and Stroot et al. (1993), we started to consider self-regulation as vital for pre-service teachers during the mentoring prior to entering the profession.

Short course development: Pre-service teacher self-regulated professionalism and teacher identity development

The construct "self-regulated professionalism" combines constructs such as self-regulated learning and professional learning. Both the pre-service teacher and mentor teacher embark on a journey of self-empowerment, an essential 21st-century feature (De Boer, Du Toit & Bothma, 2015) that suggests a constant process of "learning about learning" (Hugo, Slabbert, Louw, Marcus, Bac, Du Toit & Sandars, 2012:130), and learning about professionalism.

We support the idea that professional teacher identity is about the self (Beijaard, Meijer & Verloop, 2004; Farrell, 2011; Fraser, 2018) and regard that challenges in the profession should be handled from a constructivist perspective. The development of professional teacher identity is, therefore, not a once-off final-year teaching preparation activity. We agree with Pillen, Den Brok and Beijaard (2013:87) that "professional identity is a continually changing, active and ongoing process." The evolving teacher identity of pre-service teachers is specifically about them being confronted with their "teaching practices, teacher knowledge, beliefs and attitudes" (Steenekamp, Van der Merwe & Mehmedova, 2018:2).

Self-regulation is fittingly regarded as imperative in pre-service teacher preparation during the transition from being a student to becoming a teacher (Campbell & Brummett, 2007). Schunk and Mullen (2013:363) state that "if quality mentoring is taking place, self-regulated learning is playing an influential part." We agree with Jado (2015) that HEIs need to develop self-regulated life-long learners. This exploratory baseline study informed the construction of the curricula of two short courses in which the experiences of pre-service teachers and mentor teachers guided the design process.

Curriculum design is done in various ways and for different situations. Currently, aspects such as globalisation, 21st-century skills and evolving technologies force the reconsideration of curriculum content worldwide (Wiles & Bondi, 2015). Gosper and Ifenthaler (2014) maintain that no mutual perception of the construct "curriculum" exists in the higher education sector. The 3P model of Biggs, Kember and Leung (2001) guided the construction of the curricula of the short courses with a focus of ultimately cultivating self-regulated professionalism. The two short courses were positioned in the post-school education training field (Moon, 2014).

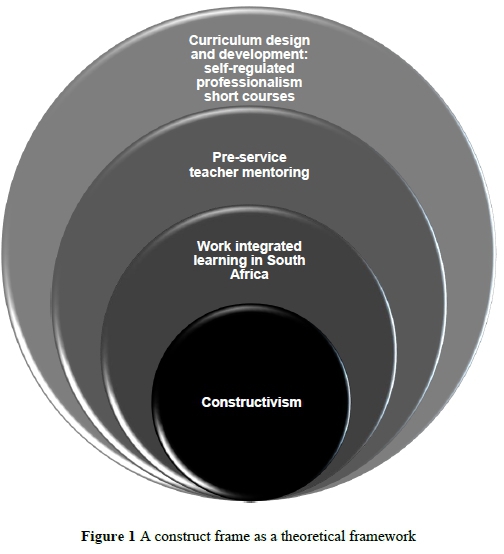

A Construct Frame as the Theoretical Framework The outer frame that supports the theoretical aspects of the study is constructivism. Inside this frame, other smaller frames exist, each representing a set of constructs derived from theories in the literature. Although various points of view regarding the denotation of constructivism exist (Hershberg, 2014; Schunk, 2012), we regard constructivism as an epistemological grounding of theories applicable to our view of mentoring. This epistemological grounding, in essence, refers to the various interrelated constructs relating to innovation. These constructs were used to inform the curricula of the short courses in a dynamic fashion - establishing it as innovative courses, informed by the exploratory baseline study data and the literature. As constructivist researchers and practitioners, we prefer to use a construct frame instead of a theoretical or conceptual framework commonly used in research studies. The construct frame shown in Figure 1 outlines the baseline constructs, which are not stagnant, but fluid.

The construct frame in Figure 1 is represented as spheres, acknowledging the integration between the baseline constructs. The framework is based on the constructivist approach. The WIL and pre-service mentoring spheres are contextually infused, and all spheres are interlinked with the design of the self-regulated professionalism short courses, bound by the foundation of constructivism. The short courses were specifically designed to be implemented for this specific context.

Methodology

Ethical clearance was obtained from the applicable HEI and permission was granted by the Dean of the Faculty. The Department of Education gave permission for the study to be conducted. The schools and mentor teachers also consented.

As stated, two cross-sectional online baseline surveys were developed and distributed - one for mentor teachers and the other for pre-service teachers. The purpose was to measure and compare attitudes, beliefs, opinions and practices (Creswell, 2012) in the South African pre-service teacher mentoring context.

Sampling

The two population groups were mentor teachers and pre-service students teaching or studying in the Pretoria area. We used non-probability, convenience sampling to select the pre-service teachers as they were "available, convenient, and representative" (Creswell, 2012:145). The sample frame included students enrolled for the Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) and pre-service teachers in the Senior and Further Education and Training phase. The sample size was 280 pre-service teachers.

The pre-service teachers were placed at 50 secondary schools in Pretoria for the WIL period. Snowball sampling was used to select the mentor teachers who participated in the study; e-mails were sent to the schools to request them to forward the online baseline survey to the mentor teachers. Sixty-five mentor teachers participated in the study.

Data Collection

The quantitative baseline study consisted of mostly multiple-response and four-scale response questions to provide a competence-base for the development of the two short courses. Some of the items in the two surveys were similar. The two surveys differed in how the questions were presented, bearing in mind the experience and background of the respondents. We developed the baseline survey outlined by Clow and James (2014) and used the Qualtrics software program to develop the surveys.

Lastly, we evaluated and piloted the surveys before we distributed them online.

Two structured online surveys were designed. We opted to design the surveys to encourage the two sample groups to respond in a constructive fashion. The two surveys had a split-questionnaire design (Clow & James, 2014) as the questions were divided into construct headings, as indicated in the results section.

The first questions requested respondents' demographic information. The pre-service and mentor teachers responded to multiple-choice questions by choosing one or more answers from the options provided. In some cases, the respondents selected one of many options. Furthermore, the Likert four-scale model was used, as we requested the respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with a statement. Towards the end of the survey there were open-ended questions and the respondents typed the answer(s) in the spaces provided. The questionnaire for pre-service teachers was distributed internally through the virtual learning environment, Blackboard Learn. The mentor teacher survey was forwarded to the participating schools as an attached link, using our Google e-mail account. The schools were politely requested to forward the link to the teachers who were mentoring pre-service teachers at the time. The mentor teachers had to click on the link and complete the online survey. According to Shih and Fan (2009:26), in general, the e-mail survey response rate is approximately 20%. In this case, the average response rate for pre-service teachers was 55%. The mentor teachers' response rate was lower, at 20%. In our view, the low mentor teacher response rate was due mainly to the fact that we could not contact them personally.

In the pre-service teacher survey, the respondents were asked questions about persons who had significantly influenced their teacher identities. The final-year education students rated their most recent mentoring experience while sharing the problems they experienced during the WIL period. In the mentor teacher survey, the participants were requested to indicate the number of years they had been in the teaching profession and the number of years they had been mentoring. The mentor teachers rated their competence to mentor and commented on the challenges when mentoring pre-service teachers. In the pre-service teacher and mentor teacher surveys, we asked questions relating to the following constructs: Mentoring experiences and the extent to which pre-service teachers were prepared for their entry into the teaching profession. The respondents also answered questions about suitable mentoring approaches, partnering during mentoring, and the fulfilment of roles during the mentorship process.

Data Analysis

The exploratory baseline quantitative data were gathered, prepared, organised and analysed using the Qualtrics software program. We created an online codebook for every survey and used descriptive quantitative analysis to describe the trends that emerged from the data. Through this detailed analysis process, the data were summarised by depicting the results in graphs and tables. We compared the responses of the mentor teachers and the pre-service teachers to the survey questions and used graphs and charts to report the data and summarised results.

Results

The Demographic Information of Respondents The 102 participating pre-service teachers were heterogeneous. Afrikaans- and English-speaking participants accounted for 51% of the total. In comparison, 13% spoke Sepedi, 9% stated that their home language was isiZulu, and the rest spoke siSwazi, isiXhosa, isiNdebele, Sesotho, Setswana and Xitsonga. The gender of the mentor teachers and pre-service teachers who completed the surveys was predominantly female (61%).

Of the 65 teachers who completed the online survey for mentor teachers, 57% were Afrikaans and 18% English speaking. Concerning mentor teachers, 22% were beginner teachers, and the majority (50%) had 11 to 20 years of teaching experience. It is especially noteworthy that the majority of the mentor teachers (53%) had up to 5 years of mentoring experience, which indicates that there is no correlation between the number of years in the teaching profession and the number of years acting as a mentor teacher for pre-service teachers.

Experiences during the Pre-Service Teacher Mentoring Period

The mentor teachers had predominantly positive mentoring experiences (90%) during the preliminary baseline study WIL period, as indicated in the bar chart in Figure 2.

The responses received from the pre-service teachers indicated a slightly different scenario with 83% having had somewhat to very positive experiences. As seen in Figure 2, none of the mentor teachers had very negative mentoring experiences, while 5% of the pre-service teachers reported negativism. The pre-service teachers indicated that the main benefit of the mentoring relationship was to gain classroom management skills (21%) followed by developing professionally and being prepared for the teaching profession. The key challenges they had during the WIL period included learner behaviour (32%), workload (16%) and the communication between the school and the University (12%). A cause for concern was that 5% of the pre-service teachers indicated no significant assistance from their mentor teachers during the WIL period. The mentor teachers rated the opportunity to develop future teachers as the most significant benefit of mentoring pre-service teachers. From the data, the respondent mentor teachers indicated that mentoring had been a challenge as final-year education students were not prepared for the realities of the profession.

Influence on the Development of Pre-Service Teacher Identity

Some pre-service teachers (7%) stated that their lecturers did not significantly influence their professional teacher identity development (Figure 3). Mentor lecturers who mentored the final-year education students during their WIL experience only had a 1% impact on their identity development.

The value of mentoring in the school context can be seen in Figure 3. In total 28% of the pre-service teachers stated that the teachers they had while still at school had influenced their teacher identities; 26% indicated that the learners whom they taught during the WIL period had influenced the formation of their teacher identities; 22% indicated that the mentor teachers had affected their teaching identities.

Pre-Service Teacher Mentoring: Competence, Roles, Approaches and Partnering

In this section, the responses obtained through the baseline surveys concerning the competence of mentor teachers to mentor, the approach used, suggestions on how mentor teachers needed to be selected and the role descriptions of the mentor and pre-service teachers are discussed. As shown in Figure 4, 26% of the pre-service teachers thought that the mentor teachers were only marginally, or not competent to mentor.

As shown in Figure 4, only 2% of the mentor teacher respondents considered themselves slightly competent to mentor a pre-service teacher. We find the result in Figure 4 noteworthy since more than 50% of the mentor teachers indicated that they had less than 5 years of mentoring experience, which, in our opinion, is an indication that they were relatively inexperienced with regard to mentoring at the time.

The independent variables in Figure 5 indicate that the pre-service teachers and mentor teachers had mostly the same idea regarding their preferred approach during pre-service teacher mentoring.

As seen in Figure 5, 69% of the pre-service teachers and 64% of the mentor teachers indicated that the most preferred approach was an interactive mentoring approach that enabled the mentor and pre-service teachers to influence one another. The respondents furthermore favoured a self-regulated mentoring approach. The mentor teacher allowed the pre-service teacher to learn through observation, reflection and action (as indicated by 27% of pre-service teachers and 25% of mentor teachers). Thirty per cent of pre-service teachers and 31% of mentor teachers regarded taking responsibility for their own learning as the principal role of pre-service teachers during mentoring (see Figure 6).

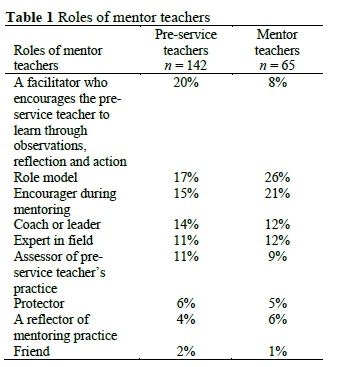

The respondents had different perceptions about the role of a mentor teacher (Table 1), with the majority of pre-service teachers expecting the mentor teachers to reflect on their practice (20%). In comparison, only 8% of the mentor teachers regarded these steps as essential and preferred instead to act as role models for the pre-service teachers. This could be the reason why 26% of the pre-service teachers did not regard their mentor teachers as competent mentors.

There is a dissimilarity between the baseline data (Table 1) and current research on the roles of mentor teachers and pre-service teachers (Ambrosetti et al., 2014). The authors acknowledge that mentor teachers and final-year education students should take responsibility for their professional learning. Therefore, the baseline data in Table 1 promote the stance for the self-regulated professionalism to be incorporated in pre-service teacher mentoring short courses.

Preparedness of Pre-Service Teachers for the Profession

To establish a competence base for the construction of the curriculum of two short courses, we asked three qualitative exploratory questions in the two online baseline surveys. The mentor teachers and pre-service teachers indicated the extent to which, in their opinion, the pre-service teachers were prepared for the profession. The majority of the final-year education students and mentor teachers indicated that personal time and classroom management of pre-service teachers needed attention.

Discussion

In this article, some of the results from a cross-sectional electronic baseline survey are shared as it informed the construction of two pre-service mentoring short courses. We do not report on a follow-up study relating to the design and implementation of the courses in this article. The curricula of the short courses (one designed for mentor teachers and the other for pre-service teachers) reflect the South African context. Moon (2014) suggests that students should have input when a curriculum is developed for them. In terms of developing the curricula of the short courses, the word "training" is not correct, since a skill, knowledge or directives for behaviour were not imparted. The baseline data, gathered through two cross-sectional surveys, provided a competence base that informed the construction of the short courses. From this baseline study, it was apparent that the roles of the mentor teacher during the WIL period was vital. The respondents agreed that a reflective, self-regulated learning mentoring practice was an essential aspect of professionalism. In collaboration with the South African Council for Educators (SACE), teachers earn professional development points (PDP) by attending short courses. The short courses we developed are informed by the baseline data and accredited by the SACE. The rationale behind the design of the short course curricula was to introduce different innovations into our practice and the practices of all involved.

In the pre-service teacher mentoring context, the mentor teachers and pre-service teachers' data from the exploratory baseline survey informed the content - the ways of mastering competencies outlined through the learning outcomes in the short courses. The respondents indicated their preparedness for a more interactive, reciprocal mentoring approach to nurture self-regulated professionalism. The approach to professional learning is graphically illustrated in Figure 7.

Apart from the quantitative data, it was important to keep relevant learning theories in mind. We used the curriculum design structure framework by Wiles and Bondi (2015), relevant literature and the quantitative data from the exploratory baseline survey to construct the short courses. As the respondents indicated in the baseline surveys, they favoured a self-regulated mentoring approach. We designed the courses in such a way that all participants were encouraged to use the principles of self-regulated professional learning. As outlined in Figure 7, from the rich data gathered and reported on, it was noticed that the study material and manuals for the short courses should incorporate the constructs of reflective, reciprocal mentoring in scholarly communities of practice. The idea was that it had to be employed in an interactive fashion. The curriculum framework design revolved around self-regulated professional learning. The construct of facilitative mentoring (Du Toit, 2017) was in line with the theoretical underpinning of the study using a constructivist lens. Moreover, we are of the view that the baseline data justified our stance for promoting the scholarship of self-regulated professionalism. The implementation of the short courses, the outcome, and the lessons learned are shared in a follow-up article.

Acknowledgements

We thank the mentor teachers and pre-service respondents for completing the surveys. We acknowledge the participating secondary schools for permission to conduct the quantitative study. We thank the WIL office and the late Professor Fraser for their willingness to assist and allow us access to ClickUp to distribute the pre-service teachers' survey.

Authors' Contributions

TS drafted and conceptualised the article. TS conducted the data collection and conducted the analysis. PHdT co-conceptualised the article. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 13 March 2020; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 16 April 2021; Published: 31 May 2021.

References

Allen TD & Eby LT (eds.) 2007. The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Ambrosetti A 2014. Are you ready to be a mentor? Preparing teachers for mentoring pre-service teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(6):30-42. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.2 [ Links ]

Ambrosetti A & Dekkers J 2010. The interconnectedness of the roles of mentors and mentees in pre-service teacher education mentoring relationships. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(6):42-55. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n6.3 [ Links ]

Ambrosetti A, Knight BA & Dekkers J 2014. Maximizing the potential of mentoring: A framework for pre-service teacher education. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 22(3):224-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.926662 [ Links ]

Ambrosetti AJ 2012. Reconceptualising mentoring using triads in pre-service teacher education professional placements. PhD dissertation. Norman Gardens, Australia: Central Queensland University. [ Links ]

Beijaard D, Meijer PC & Verloop N 2004. Reconsidering research on teachers' professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2):107-128. https://doi.org/10.10167j.tate.2003.07.001 [ Links ]

Biggs J, Kember D & Leung DYP 2001. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(1):133-149. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158433 [ Links ]

Bozeman B & Feeney MK 2007. Toward a useful theory of mentoring: A conceptual analysis and critique. Administration & Society, 39(6):719-739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707304119 [ Links ]

Brondyk S & Searby L 2013. Best practices in mentoring: Complexities and possibilities. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 2(3):189-203. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-07-2013-0040 [ Links ]

Buell C 2004. Models of mentoring in communication. Communication Education, 53(1):56-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452032000135779 [ Links ]

Burghes D, Howson J, Marenbon J, O'Leary J & Woodhead C 2009. Teachers matter: Recruitment, employment and retention at home and abroad. London, England: Politeia. Available at https://www.politeia.co.uk/wp-content/Politeia%20Documents/2009/July%20-%20Teachers%20Matter/Teachers%20Matter'%20July%202009.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2021. [ Links ]

Butler BM & Cuenca A 2012. Conceptualizing the roles of mentor teachers during student teaching. Action in Teacher Education, 34(4):296-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.717012 [ Links ]

Campbell MR & Brummett VM 2007. Mentoring pre-service teachers for development and growth of professional knowledge. Music Educators Journal, 93(3):50-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/002743210709300320 [ Links ]

Clow KE & James KE 2014. Essentials of marketing research: Putting research into practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Clutterbuck D & Megginson D 1999. Mentoring executives and directors. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Crisp G & Cruz I 2009. Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50:525-545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2 [ Links ]

Crow GM 2012. A critical-constructivist perspective on mentoring and coaching for leadership. In SJ Fletcher & CA Mullen (eds). The Sage handbook of mentoring and coaching in education. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond L & McLaughlin MW 2011. Policies that support professional development in an era of reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6):81-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171109200622 [ Links ]

Dawson P 2014. Beyond a definition: Toward a framework for designing and specifying mentoring models. Educational Researcher, 43(3):137-145. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14528751 [ Links ]

De Boer AL, Du Toit PH & Bothma T 2015. Activating whole brain® innovation: A means of nourishing multiple intelligence in higher education. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(2):55-72. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa 2015. National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Revised policy on the minimum requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Government Gazette, 596(38487), February 19. Available at https://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/National%20Qualifications%20Framework%20Act%2067_2008%20Revised%20Policy%20for%20Teacher%20Education%20Quilifications.pdf. Accessed 6 March 2019. [ Links ]

Du Plessis EC & Marais P 2013. Emotional experiences of student teachers during teaching practice: A case study at Unisa. Progressio, 35(1):206-222. [ Links ]

Du Toit PH 2017. Workshop on innovative mentoring. 19 September. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Ehrich L, Hansford B & Ehrich JF 2011. Mentoring across the professions: Some issues and challenges. In J Millwater & D Beutal (eds). Practical experiences in professional education: A transdisciplinary approach. Brisbane, Australia: Post Pressed. [ Links ]

Farrell TSC 2011. Exploring the professional role identities of experienced ESL teachers through reflective practice. System, 39(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.01.012 [ Links ]

Fletcher SJ & Mullen CA (eds.) 2012. The Sage handbook of mentoring and coaching in education. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Fraser WJ 2018. Filling gaps and expanding spaces -voices of student teachers on their developing teacher identity. South African Journal of Education, 38(2):Art. # 1551, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n2a1551 [ Links ]

Geber H & Nyanjom JA 2009. Mentor development in higher education in Botswana: How important is reflective practice? South African Journal of Higher Education, 23(5):894-911. Available at https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC37567. Accessed 21 June 2018. [ Links ]

Gosper M & Ifenthaler D (eds.) 2014. Curriculum models for the 21st century: Using learning technologies in higher education. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7366-4 [ Links ]

Herrera C, Kauh TJ, Cooney SM, Grossman JB & McMaken J 2008. High school students as mentors: Findings from the big brothers big sisters school-based mentoring impact study. Philadelphia, PA: Public/Private Ventures. [ Links ]

Hershberg RM 2014. Constructivism. In D Coghlan & M Brydon-Miller (eds). The Sage encyclopedia of action research (Vol. 1). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Hudson P 2013. Mentoring as professional development: 'Growth for both' mentor and mentee. Professional Development in Education, 39(5):771-783. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.749415 [ Links ]

Hugo JF, Slabbert J, Louw JM, Marcus TS, Bac M, Du Toit PH & Sandars JE 2012. The clinical associate curriculum - the learning theory underpinning the BCMP programme at the University of Pretoria. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 4(2): 128-131. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.188 [ Links ]

Ioannidou-Koutselini M & Patsalidou F 2015. Engaging school teachers and school principals in an action research in-service development as a means of pedagogical self-awareness. Educational Action Research, 23(2):124-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2014.960531 [ Links ]

Jado SMA 2015. The effect of using learning journals on developing self-regulated learning and reflective thinking among pre-service teachers in Jordan. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(5):89-103. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1083603.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2021. [ Links ]

Jansen JD 2002. Political symbolism as policy craft: Explaining non-reform in South African education after apartheid. Journal of Education Policy, 17(2):199-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110116534 [ Links ]

Kemmis S, Heikkinen HLT, Fransson G, Aspfors J & Edwards-Groves C 2014. Mentoring of new teachers as a contested practice: Supervision, support and collaborative self-development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43:154-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.001 [ Links ]

Kram KE 1983. Phases of the mentor relationship. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4):608-625. https://doi.org/10.5465/255910 [ Links ]

Long J 1997. The dark side of mentoring. The Australian Educational Researcher, 24(2):115-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219650 [ Links ]

Lynch D & Smith R 2012. Teacher education partnerships: An Australian research-based perspective. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(11):132-146. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n11.7 [ Links ]

Moon J 2014. Short courses and workshops: Improving the impact of learning, teaching and professional development. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315042367 [ Links ]

Pillen MT, Den Brok PJ & Beijaard D 2013. Profiles and change in beginning teachers' professional identity tensions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 34:8697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.04.003 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Schunk DH 2012. Learning theories and educational perspective. Boston, MA: Pearson. Available at http://repository.umpwr.ac.id:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/96/[Dale_H._Schunk]_Learning_Theories_An_Educational..pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 30 May 2021. [ Links ]

Schunk DH & Mullen CA 2013. Toward a conceptual model of mentoring research: Integration with self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 25:361-389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9233-3 [ Links ]

Shih TH & Fan X 2009. Comparing response rates in email and paper surveys: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 4(1):26-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2008.01.003 [ Links ]

Steenekamp K, Van der Merwe M & Mehmedova AS 2018. Enabling the development of student teacher professional identity through vicarious learning during an educational excursion. South African Journal of Education, 38(1):Art. # 1407, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n1a1407 [ Links ]

Stroot SA, Faucette N & Schwager S 1993. In the beginning: The induction of physical educators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 12(4):375-385. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.12A375 [ Links ]

Walkington J 2005. Mentoring pre-service teachers in the preschool setting: Perceptions of the role. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 30(1):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910503000106 [ Links ]

Wiles J & Bondi J 2015. Curriculum development: A guide to practice (9th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]