Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40ns2a1444

ARTICLES

Transition from special school to post-school life in youths with severe intellectual disability: Parents' experiences

Emalda EllmanI; Amshuda SondayII; Helen BuchananIII

IDepartment of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa and Western Cape Education Department, Cape Town, South Africa

IIDepartment of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa helen.buchanan@uct.ac.za

IIIDepartment of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Transitions are important landmarks in the educational career of youths, as successful transitions prepare them for adult life. When youths with disabilities leave school, the transition to post-school life is accompanied by several challenges. To our knowledge, there is currently limited information about how parents of youths with severe intellectual disabilities in South Africa experience this transition process. The study reported on here aimed to describe parents' experiences of the transition of their child with severe intellectual disability from special school to post-school in a small town in the Western Cape, South Africa. A qualitative descriptive study using in-depth semi-structured interviews was conducted with 5 parents of youths with severe intellectual disability. Inductive analysis of the transcripts yielded 2 themes: "It really hit us hard", and "adjustment to post-transition life." The findings indicate that the meanings that parents attribute to their experience of transition are influenced by their personal responses and coping strategies within the context in which they find themselves during the transition period. Occupational therapists can assist in providing smoother transitions for youths with disabilities. Recommendations include addressing transition services on policy level.

Keywords: disability; education; parents; school to post-school; severe intellectual disability; South Africa; special school; transition; transition planning; youths

Introduction

Transitions are a natural part of life for all people (Stewart, 2013). Many forms of transition take place in a person's life - transitions to day-care, primary school, secondary school, further education and training, tertiary education, leaving home, first job, buying a home and so forth. Youths leaving mainstream high schools are excited about new possibilities, such as further education and training, employment, and other options that lead to independence (Cooney, 2002; Dewson, Aston, Bates, Ritchie & Dyson, 2004; McGill, Tennyson & Cooper, 2006). However, this transition on leaving school does not occur naturally for youths with disabilities. Studies from Australia and America report that young people with intellectual disabilities (ID) and their families find the transitional experience from school to post-school life quite demanding (Kim & Turnbull, 2004; Winn & Hay, 2009). The transition is usually accompanied by several challenges including difficulty finding employment due to high unemployment levels, restricted community participation, continued living with parents and dependence on the family (Davies & Beamish 2009).

Occupational therapists support the transition process for families and children with and without disabilities, enabling children to develop and become as independent as possible (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008). Occupational therapists possess unique skills that enable them to play a vital role in the transition planning for youths with disabilities (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008; Kardos & White, 2006; Mankey, 2011; Miller, 2012). Miller (2012:135), however, suggests that "school-based occupational therapists in America are currently not fulfilling their full potential as secondary transition service providers within the school system." In the South African context, the role of school-based occupational therapists primarily involves facilitating the transition process and providing prevocational preparation, vocational training and job placement (Nel & Van der Westhuyzen, 2009).

In 2001, the South African government launched Education White Paper 6, a 20-year plan to address shortcomings in the education system (Department of Education, 2001). The White Paper highlighted inadequate opportunities for programme-to-work linkages as a barrier to learning and development (Department of Education, 2001). In addition, the lack of parental recognition and involvement has been identified as causing learning barriers (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2005a). Long-term plans from the White Paper include the "development of an inclusive education and training system that will uncover and address barriers to learning, and recognise and accommodate the diverse range of learning needs" (Department of Education, 2001:45). According to this plan, the role of special schools is to offer "comprehensive education programmes that provide life-skills training and programme-to-work linkages" (Department of Education, 2001:21). The latter part of this statement alludes to the transition from school into employment. Unlike countries such as the United States of America (USA) and Canada, which are compelled by law to provide guidelines to smooth transition planning for youths with disabilities (King, Baldwin, Currie & Evans, 2005; Mankey, 2011), South Africa does not have legislation that addresses this transition.

According to Vlachos (2008), every school has the responsibility to provide transition planning for school leavers, which should ideally be the role of the life skills teacher. The South African Department of Basic Education makes provision for alternative teaching methodologies, strategies and assessment (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2011:4), which align with the Department's policy on inclusion. However, while the Department of Education, Republic of South Africa (2005a) refers to an individual learning plan as a viable option for addressing the needs of learners who continue to experience barriers to learning, transition from school to post-school is not addressed. This gap in policy suggests that more planning is needed for the transitions of children with severe intellectual disability (SID) within the South African schooling system, and more specifically to consider post-school options.

Planning for transition assists disabled youths and their parents to prepare for an event that can otherwise be traumatic. Accessing information can instil a feeling of confidence in moving from one environment to the next. Conversely, research suggests that when transition planning is neglected or deemed unimportant, parents become stressed, as they do not know what to expect once the child reaches transition age (Kraemer & Blacher, 2001). Various studies report the school-to-post-school transition as a stressful period for parents of children with ID (Bennie, 2005; Beresford, 2004; Kraemer & Blacher, 2001; Smart, 2004; Ward,

Mallett, Heslop & Simons, 2003). In addition, parents are often only marginally involved in the transition process and planning thereof for their child (Bhaumik, Watson, Barrett, Raju, Burton & Forte, 2011; Davies & Beamish, 2009). As children with severe disabilities frequently remain at the same school, they do not experience the transition from primary to secondary school, and parents are, therefore, inexperienced when the school-to-post-school transition occurs (Hurst, 2009). When these parents are either not involved or only partially involved in transition planning for their child, they are likely to experience the transition as stressful.

Transitions such as those from school to post-school, may entail assuming new occupations,i blending them with existing ones and giving up some occupations (Shaw & Rudman, 2009). This conceptualisation of a transition as an occupational transition falls within the discipline of occupational science which studies "how such changes ... are negotiated by individuals" and "how they are shaped by broader environmental features" (Shaw & Rudman, 2009:362). Research has shown that contexts are very influential on occupational performance (Dunn, Brown, McClain & Westman, 1994; Green, 2002). The transition experience explored in this study occurred in the environmental context of a small town in the Western Cape of South Africa. The town, located approximately 150 km from the nearest city, has no established transport system and thus parents are dependent on the limited options available within the town. The study sought to answer the following research question: What are parents' experiences regarding the transition from special school to post-school of their child with intellectual disability?

Study Aim and Objectives

This study aimed to describe how parents experienced the transition from special school to post-school of their child with SID in a small town in the Western Cape. The objectives were to: (a) describe parents' personal responses linked to the transition, (b) describe the strategies parents used to cope with the transition, and (c) identify the contextual factors that influenced their experience.

Methodology

Research Approach

A qualitative approach was followed to best answer the research question as there was an interest in describing the experiences of parents in context. This was best suited to this study as qualitative research "stud[ies] focus on things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them" (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005:3).

Research Design

A qualitative descriptive research design was most appropriate for this research as it served to demonstrate how participants experienced the world. Furthermore, "qualitative descriptive studies offer a comprehensive summary of an event in the everyday terms of those events" (Sandelowski, 2000:336). This design also offered a lens to gain an understanding of the experiences of parents as their child transitions from school to post-school.

Population and Sampling

The study population comprised parents of SID youths living in a small town in the Western Cape who had experienced school-to-post-school transition. Participants were recruited through a non-governmental organisation (NGO) for people with disabilities in the town. Purposive sampling, specifically, criterion sampling, was used deliberately to select individuals based on predetermined criteria (Creswell, 2007). Participants were selected for their ability to contribute to an understanding of the research problem (Creswell, 2007). The following criteria were used to select five participants:

1) Parents (biological or adoptive) of a child with SID residing in the afore-mentioned town whose child:

• had attended a special school for learners with ID,

• was between 18 and 35 years of age, and

• had experienced a transition from school to post-school.

2) Parents who had sufficient verbal communication skills in English or Afrikaans to describe their experiences.

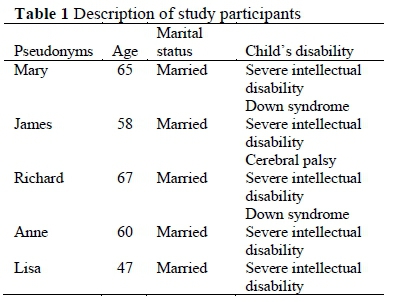

Details of the five participants are shown in Table 1.

Data Collection

Data were collected using individual in-depth semi-structured interviews. This method was chosen to enable the five participants to express themselves more freely and to share their thoughts, feelings and opinions. Two questions were asked - "Tell me about your experience with the transition of your child from school", and "What contexts or situations have influenced or affected your experiences of transition for your child?" Each participant was interviewed twice; in-depth information was gathered in the first interview, and the second interview elicited further details about the participants' experiences (Seidman, 2006). Interviews lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes. Four participants were interviewed in their homes and one was interviewed at the NGO. The interviews were conducted in Afrikaans or English - whichever language that participants were most comfortable using. An independent researcher translated the Afrikaans interviews into English.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded with a Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim by the first author. Inductive analysis with a content analysis approach was followed to allow themes and categories to emerge from the data (Mayring, 2000). Mayring's (2000) content analysis steps involve developing a criterion definition (based on the research question and underpinning theory) to establish which parts of the transcriptions will be considered, working through the data to identify categories, revising and reducing the categories until the main categories emerge, checking reliability of the main categories, and finally, interpreting the results. In this study, the criteria for selecting codes in the transcribed data were any references to parents' personal responses to their child's transition and coping strategies that they employed to manage their transition experience. The first author identified the data codes with the guidance of the second and third authors, and then worked through the codes to identify provisional categories. These categories were revised in collaboration with the second and third authors until the final themes and categories emerged.

Ensuring Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured using the strategies of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Krefting, 1991). Credibility was achieved by sufficient submergence in the research setting in order to identify and verify recurring patterns. Several strategies were used to address credibility in this study. Firstly, the first author familiarised herself with the participating organisation early on in the research process to build a trusting relationship; secondly, the sampling method ensured that diverse participants with a wide range of perspectives were selected; thirdly, peer scrutiny occurred throughout the research process, and finally through member checking of the findings. To achieve transferability, dense information about the participants, the context and setting were provided. Dependability was accomplished through accurate description of the methods of data gathering, analysis and interpretation. Confirmability was addressed through involving a team of researchers throughout the research process. Once the data were analysed, member checking took place to ensure that the findings were accurate.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC reference number: 625/2012). All participants were informed about their right to confidentiality and anonymity. Pseudonyms were used to protect participants' identities. Audio-recordings and transcriptions were stored on a password protected computer. Hard copies were securely stored in a locked cupboard to which only the first author had access.

Findings

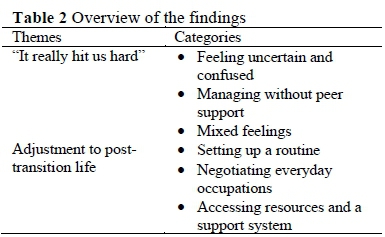

Two themes with three categories each emerged from the data (see Table 2 for an overview).

Theme 1: "It Really Hit Us Hard" This theme captures the participants' response to the transition experience as they came to terms with the realities that they faced. The transition influenced their lives in ways that they had not anticipated and that had a profound effect on them.

The first category "feeling uncertain and confused" describes their unfamiliarity with what was happening that was marked by feelings of uncertainty and bewilderment. This was attributed to not knowing what was expected of them and what was going to happen. Participants felt restricted in their daily lives and felt that, at least for a short while, life came to a standstill and they were not able to make decisions.

You are without counsel because you don't know what's going to happen next. My wife and I had to plan, you always had to plan that there's someone at home or that she had to move with us, which was difficult because you can't leave her on her own. That also limited us in a way ... like when you want to go out or if you get an invitation, because you have somebody. (James)

Parents felt that the uncertainty was exacerbated by poor communication from the school. Although they expressed deep gratitude, appreciation and trust in the educators and staff of the special school, participants asserted that no one at the school had communicated with them about the transition. Some participants recalled the school advising them that when their child turned 18, he/she would have to leave school. They also felt that the school could have better prepared them for what they could expect. Where the school had arranged post-school placements, participants lacked information about the placement, which left them feeling unable to prepare themselves or their child adequately for the transition.

The school did not communicate with us about [NGO name] or that the child is completing his school year and we were really not properly prepared for this transition and it really hit us hard once the child actually completed their schooling and had to go to a new environment which we did not know or understand and it was foreign to the child as well. (Lisa)

Lacking knowledge about the transition from school was common among all the participants in the study. Not knowing what was going to happen next caused an uncertainty about the future that made the transition period challenging. An added obstacle was the limited options for post-school placement for youths with SID in the study setting. As parents were aware of this, they felt overwhelmed and uncertain about the future. In addition, they felt inadequately prepared to make decisions to accommodate changes caused by the transition, which were life changing and often influenced their lives substantially.

I was not ready yet, not ready to leave my job. Ifelt I still wanted to work but did not have a choice. I, I, I... always felt she is my problem and I could not expect or ask other people to look, to take care of her because it's my problem. (Anne)

In the second category "managing without peer support", participants described the transition as a time of coping on their own. They felt that the burden was theirs and that they could not involve others; they did not want to intrude on people or be a nuisance to them. Most participants embraced their situation of being alone, handled circumstances as they arose and carried on with their lives. However, they felt as though the people close to them did not care, which made them feel hurt.

I just accepted that he was our problem over and out ... This is my child and I have to deal with him. So we didn't have support from anywhere ... I never received any support from family or friends, or help or so on. (Mary)

Participants spoke about the disparity in how their ID child was treated compared with their other children. Some participants said that family and friends never offered to help because they were not used to their child with SID. The transition brought a sense of loneliness for many parents. They rarely asked for help and people seldom reached out to them. Although there was a general longing to engage with others, participants never initiated or created opportunities to engage. This affected their lives as they missed opportunities to enjoy life and felt that life was slipping past them.

If you have a disabled person, child or adult, then you don't have friends ... As soon as you have such a person then there's not friends for you. I don't know what the problem is. ... Sometimes you long for people to come to you. (Lisa)

This is a lonely road, a very alone road (James)

. The third category "mixed feelings" describes the fluctuations in participants' feelings while going through the transition. Although some experiences were positive, most were negative. Feelings were influenced by context, specifically the physical and social environment. At certain intervals during the transition, parents were happy, content and even experienced joy, which they described as positive. However, their location in relation to the city raised awareness of the lack of resources available to them in the area. Most participants had previously experienced sending their child away from home to the city to access education. One parent reflected on his first encounter with transition when his young son was left behind at a school for learners with SID in the city. He seemed to relive the emotional turmoil and pain he had experienced then. To avoid similar experiences during this transition, parents were grateful to have options available in the area - even though they were limited. They were, therefore, pleased when members of an NGO came to recruit disabled people for their organisation as it provided an alternative to staying at home and contributed to a more positive experience of the youth's transition. In the words of one father, "It was much easier because he was closer. He came home every night. It was much easier for me. I am happy. He is happy. It was positive" (Richard).

On the other hand, there were also negative experiences that seemed to outweigh the positives. Parents disclosed frequently feeling stressed, worried and uneasy. Some were anxious because they had work responsibilities that required their attention and they could not find suitable people to look after their child. Others felt confined or restricted with no hope for the future. These feelings seemed to be exacerbated when participants lacked information, which limited their ability to plan. Some parents viewed the transition as the end of a road, saying that life had come to a standstill. In cases where no NGOs were available at the time, youths were compelled to stay at home and parents, especially mothers, had to stay home with them. For these parents the transition resulted in forced isolation. One mother said: 'We can't go out anywhere as we like, if you go out you want to relax ... but it's not possible" (Lisa).

One participant - a career woman - felt troubled about staying at home years before her retirement age. Her decision to stay at home influenced her financial independence negatively and contributed to her ambivalence towards the transition.

Theme 2: Adjustment to Post-Transition Life This theme captures the participants' experiences as they grappled with changes in their personal lives during the transition. This led them to develop coping strategies.

The first category "setting up a routine" gives some insight into how participants' personal routines were altered. For some it meant having time to relax as the morning rush of readying their child for school no longer applied. On the other hand, parents found that the transition placed certain limitations on their personal routines. One participant explained that having her child at home created a barrier to her usual morning routine, as her daughter would constantly call on her to do things like change the television channel or bring her something to eat, which disrupted her schedule.

Participants shared that being at home was strange for their child as well. Engaging in household activities, which had previously been fun, were no longer pleasurable. Some parents arranged playdates with other youths with SID to create opportunities for socialisation, but this impacted negatively on their own routines. For example, the youths struggled to understand one another when engaging in conversation due to poor speech, which required the parents to intervene.

For some parents, the transition opened doors to establish new routines. Some volunteered their services at the NGO where their child attended to assist with the daily running of the organisation, while others became involved in their community. Through assisting at the NGO, parents were also able to keep an eye on their children and facilitate the process of settling in: "Lately I've volunteered at [name of NGO] as a parent, I'm there every day . I speak with the other children there and this also contributed to him fitting in more easily" (Anne).

For this parent, it meant a great deal that her son was now fitting in. She enjoyed volunteering at the NGO as it provided her with the peace of mind she needed because she was able to observe her child's interactions during the day. Other parents experienced no significant change in their routines as the only difference was in exchanging one destination (school) for another (NGO). This allowed them to continue in more or less the same manner as they had when their child went to school.

The second category "negotiating everyday occupations" encompasses participants' struggles with making practical household arrangements during the transition period. For some this meant waking up very early to prepare for the day and to prepare breakfast for their child. Parents had to communicate continually with their spouse and others about daily schedules such as carrying a house key, preparing meals and driving, especially for children with high support needs that were unable to take on these roles and responsibilities. Hence, participants had to balance work and social obligations to create stability to accommodate the needs of their child. In households where both parents were working, negotiating shifts became important to the general functioning within the home. As both parents were responsible for caring for their child, they had to first care for themselves to avoid burnout. Therefore, taking turns to work provided relief for participants: "There was a time when she worked day shift and I worked night shift so we could relief [sic] one another" (James).

School holidays were particularly challenging when there was no one to take care of or supervise the child. Parents were compelled to take the child to work, which required them to have a good relationship with their employer. One parent explained that her employer understood her situation as he also had a son with ID and he allowed her to take her son to work during school holidays and occasions when there was no one to take care of him. Other parents did not have the same experience and felt the only option available was to leave the job they loved.

Participants described the effort required to perform ordinary occupations and activities of daily living. Going on an outing required thorough research of the area to be visited, especially when the child used a wheelchair. Outings often proved challenging and parents frequently had to rely on others to stand in when they had to go somewhere urgently.

The third category "accessing resources and a support system" captures how many of the participants accessed support to help sustain and enhance their quality of life during the transition process. Participants drew on resources such as their faith in a higher power, families, personal skills and abilities, organisations and influential people in the community, of which they had previously been unaware. These resources helped them to deal more effectively with the transition. Feeling frustrated and weak and not wanting to burden others with their problems, they turned to their faith and opted to pray instead. Their spirituality seemed to sustain them during lonely times when they did not feel comfortable communicating with others, but instead felt that speaking to God was the only option: "... you can just ask the Lord to help you because who can help you through that loneliness^ (Anne).

Participants felt prompted to become involved in a local NGO for various reasons. Some, driven by concern for their children's safety, volunteered their services to keep an eye on them. Others noticed that the NGOs were short-staffed and decided to assist, while others volunteered their services to secure a place for their child at the organisation.

The financial burden was a real strain for some families. One participant' s wife left her job to be a full-time caregiver to their child with their only support coming from the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) disability grant. Other participants similarly claimed that the "SASSA money" was all the support they received. For some, family members, especially participants' own children and grandchildren, provided relief during times of difficulty. This almost invisible resource of siblings providing assistance was also constantly available to parents during the transition period.

Discussion

This study provides a developing-country perspective of how parents experienced the post-school transition of youths with intellectual impairment. The findings suggest that the participants' experiences of the transition were largely influenced by the interaction between their personal responses, the coping strategies that they employed and the contexts in which they experienced the transition.

Personal responses and coping strategies are embedded in the context, which consists of temporal (chronological and developmental age, life cycle and disability status) and environmental (physical, social and cultural) aspects (Dunn et al., 1994). In this study, participants' personal responses and coping strategies influenced one another and the context, in turn, impacted them both. The environmental context in which the transition occurred elicited a personal response from the parents that prompted them to apply coping strategies to address or alleviate the impact of the transition. The environmental context also drove parents to employ coping strategies. Due to the limited options available, one mother decided to leave her job in order to take care of her daughter. However, this coping strategy led to her feeling stressed and socially isolated. The participants' experiences of the coping strategy being successful or not, induced them to either continue using the strategy, to alter it, or to try a new one. Thus, the response appeared to occur at an individual level.

At the time of their child' s transition from school, the participants struggled to manage their everyday occupations. They found it particularly challenging to continue with paid work or to work the same shifts, manage their homes and socialise. Once they stopped engaging in occupations that were meaningful to them, parents experienced the transition negatively. They described emotions such as stress, anxiety, frustration and uncertainty due to the limited options available to their children, which concur with the findings of several previous studies (Beresford, 2004; Cooney, 2002; Davies & Beamish, 2009; Gillan & Coughlan, 2010; Kraemer & Blacher, 2001; Rapanaro, Bartu & Lee, 2008).

Mothers, who acted as primary caregivers, felt unprepared for the transition and experienced stress, anxiety, worry and frustration. This feeling of unpreparedness for the transition from special school by parents has also been reported in other studies (Bhaumik et al., 2011; Chambers, Hughes & Carter, 2004, Gillan & Coughlan, 2010; Raghavan, Pawson & Small, 2013; Ward et al., 2003). Learners with ID have diverse needs that are unique to the individual (Ellman, 2004). Therefore, unlike their mainstream counterparts, parents of youths with SID have to consider their children's unique support needs; they have to ensure that their child is properly cared for and is safe, while simultaneously providing enabling opportunities. A lack of information about the transition could potentially place their already vulnerable child at risk of exploitation or abuse. The guidelines for inclusive learning programmes (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2005b) outline a vision of working collaboratively with parents. Special schools can contribute by providing parents with information to reduce some of the stress associated with the school-to-post-school transition. In addition, involving parents in the transition process could be beneficial to youths with SID, their parents and the school.

Participants in this study were dissatisfied that they were not involved in the transition process, an occurrence noted in the literature (Bhaumik et al., 2011; Chambers et al., 2004; Gillan & Coughlan, 2010; Raghavan et al., 2013; Ward et al., 2003). Johnson's (2003) four steps in the basic transition process (planning, preparation, linkage and exit) view parents and family as integral to this process. Bennie (2005) similarly views parents as integral to the team and suggests that they should be active, contributing team members from the start. He argues that it could be problematic if planning is left to the last year or two of schooling. Therefore, a concerted effort should be made to introduce a transition plan early on, that defines the learners' long-term goals once they leave school. In other contexts, the transition plan forms part of the individual education plan (Bennie, 2005), referred to as an individual learning plan (ILP) in the South African context (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2005a). The ILP is a document capturing the specific learning needs of an individual with special needs (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2005a). It consists of "an individual learning programme, a work schedule or work plan and the specific adapted lesson plans" (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, 2005a:20). Although this document provides valuable information about the youths' educational support needs while at school, it does not provide a collaborative future plan for when they leave school.

Literature suggests that parents and caregivers are frequently poorly informed about post-school options for youths reaching transition age (Bhaumik et al., 2011; Chambers et al., 2004; Raghavan et al., 2013). In South Africa, it is not clear who is responsible for the transition planning of learners but it is said to be primarily the role of the guidance teacher (Vlachos, 2008). In other parts of the world, occupational therapists are viewed as key members of the transition team as they have the skills to support learners' functioning and performance in activities of daily living as well as engagement in occupation (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2014). Occupational therapists in special schools in South Africa are an untapped resource uniquely skilled to deal with transition planning and are in a position to meet with parents without placing pressure on the curriculum. It is suggested that transition planning should begin early, possibly at the age of 12 years, and that parents should be involved and receive written feedback regarding the transition plan (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008). Furthermore, parents should receive ongoing support during the transition process.

Recommendations

A national policy should be developed to address transition services specifically for this vulnerable group. With regard to practice, the occupational therapy role as it relates to school-based transition should be more clearly defined in South Africa. Collaboration should be improved among key role players within education, such as occupational therapists, educators, circuit-based education officials and parents. Future studies should address the transition of learners from special schools from differently resourced areas in South Africa, as a different context may yield different findings. Studies should also look into South African occupational therapists' involvement in transition services in special schools. An intervention to address transition issues with parents and learners should be developed and tested to address specific elements of the transition from school. Studies that explore how the youth with ID experience this transition could contribute to the existing research in this area.

Conclusion

This research found that the parents' experiences of the transition was influenced by their personal responses and coping strategies in the context in which they found themselves. The research also revealed that occupational therapists in special schools in South Africa could render a much greater service to reduce the stress experienced by parents during the transition period. Transition planning should be more organised and structured. Accountability should be assumed by a specific division within the Department of Education to achieve the goal of preparing parents and youths with ID for the special-school-to-post-school transition in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the parents who participated in this study as well as the University Research Committee at the University of Cape Town for funding this study.

Authors' Contributions

All authors conceptualised the study which EE conducted as part of a masters' degree. EE conducted the participant interviews and AS and HB assisted with data analysis. EE wrote the first draft of the article. All authors contributed to all drafts and reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. In occupational therapy, occupations "refer to the everyday activities that people do as individuals, in families and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life. Occupations include things people need to, want to and are expected to do" (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2012:para. 2).

ii. This article is based on the masters' dissertation of Emalda Ellman.

iii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association 2008. FAQ: Occupational therapy's role in transition services and planning. Bethesda, MD: Author. Available at http://www.web-kids.org/uploads/1/3/5/3/1353427/faq_ot_role_in_transition.pdf. Accessed 6 February 2012. [ Links ]

American Occupational Therapy Association 2014. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process 3rd edition. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Suppl. 1):S1-S48. [ Links ]

Bennie G 2005. Effective transition from school to employment for young people with intellectual disabilities in New Zealand (Country Report for 25th Asia-Pacific International Seminar on Special Education National Institute of Special Education, Japan). Palmerston North, New Zealand: Ministry of Education. Available at https://www.nise.go.jp/cms/resources/content/383/d-240_16.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2020. [ Links ]

Beresford B 2004. On the road to nowhere? Young disabled people and transition. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30(6):581-587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00469.x [ Links ]

Bhaumik S, Watson J, Barrett M, Raju B, Burton T & Forte J 2011. Transition for teenagers with intellectual disability: Carer's perspectives. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(1):53-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00286.x [ Links ]

Chambers CR, Hughes C & Carter EW 2004. Parent and sibling perspectives on the transition to adulthood. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 39(2):79-94. [ Links ]

Cooney BF 2002. Exploring perspectives on transition of youth with disabilities: Voices of young adults, parents, and professionals. Mental Retardation, 40(6):425-435. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040%3C0425:EPOTOY%3E2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Davies MD & Beamish W 2009. Transitions from school for young adults with intellectual disability: Parental perspectives on "life as an adjustment". Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(3):248-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250903103676 [ Links ]

Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (eds.) 2005. The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2011. Guidelines for responding to learner diversity in the classroom through Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/GUIDELINES%20FOR%20RESPO NDING%20TO%20LEARNER%20DIVERSITY %20%20THROUGH%20CAPS%20(FINAL).pdf?ver=2016-02-24-110910-340. Accessed 27 June 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Education White Paper 6. Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/Specialised-ed/documents/WP6.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2005a. Curriculum adaptation guidelines of the Revised National Curriculum Statement. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/adaptation_guidlines.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2005b. Guidelines for inclusive learning programs. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://gimmenotes.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Guidelines-for-inclusive-learning-programmes.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2020. [ Links ]

Dewson S, Aston J, Bates P, Ritchie H & Dyson A 2004. Post-16 transitions: A longitudinal study of young people with special educational needs: Wave two (Research Report No. 582). Nottingham, England: Department for Education and Skills (DfES Publications). Available at http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/rr582.pdf. Accessed 6 February 2010. [ Links ]

Dunn W, Brown C, McClain LH & Westman K 1994. The ecology of human performance: A contextual perspective on human performance. In CB Royeen (ed). The practice of the future: Putting occupation back into practice. Rockville, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association. [ Links ]

Ellman B 2004. The experience of teachers in including learners with intellectual disabilities. MEd thesis. Stellenbosch, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch. Available at http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/50152. Accessed 24 May 2020. [ Links ]

Gillan D & Coughlan B 2010. Transition from special education into postschool services for young adults with intellectual disability: Irish parents' experience. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(3):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00265.x [ Links ]

Green MC 2002. Promouvoir l' ergotherapie; notre facon de nous percevoir [Promoting occupational therapy; how we see ourselves]. Occupational Therapy Now, 4(4):32-33. [ Links ]

Hurst J 2009. The challenges of maintaining occupation at times of transition. In J Goodman, J Hurst & C Locke (eds). Occupational therapy for people with learning disabilities. A practical guide. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-10299-8.00009-5 [ Links ]

Johnson JR 2003. Parent and family guide to transition education and planning. What parents and families need to know about transition education and planning for youth with disabilities: An insider's perspective. Available at https://www.esc1.net/cms/lib/TX21000366/Centricity/Domain/99/what_parents_need_to _know_about _transition_planning.pdf. Accessed 6 February 2012. [ Links ]

Kardos MR & White BP 2006. Evaluation options for secondary transition planning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60:333-339. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.60.3.333 [ Links ]

Kim KH & Turnbull A 2004. Transition to adulthood for students with severe intellectual disabilities: Shifting toward person-family interdependent planning. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29(1):53-57. Available at https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/6250/PCPF7_Transition_to_Adulthood _8_07.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 25 April 2020. [ Links ]

King GA, Baldwin PJ, Currie M & Evans J 2005. Planning successful transitions from school to adult roles for youth with disabilities. Children's Health Care, 34(3):193-216. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326888chc3403_3 [ Links ]

Kraemer BR & Blacher J 2001. Transition for young adults with severe mental retardation: School preparation, parent expectations, and family involvement. Mental Retardation, 39(6):423-435. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2001)039%3C0423:TFYAWS%3E2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

Krefting L 1991. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45:214-222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214 [ Links ]

Mankey TA 2011. Occupational therapists' beliefs and involvement with secondary transition planning. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Paediatrics, 31(4):345-358. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2011.572582 [ Links ]

Mayring P 2000. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2):Art. 20. [ Links ]

McGill P, Tennyson A & Cooper V 2006. Parents whose children with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour attend 52-week residential schools: Their perceptions of services received and expectations of the future. The British Journal of Social Work, 36(4):597-616. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch297 [ Links ]

Miller E 2012. Occupational therapists' intervention approaches in secondary transition services for students with disabilities. MS thesis. Richmond, KY: Eastern Kentucky University. Available at https://encompass.eku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi7referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1082&context=etd. Accessed 6 February 2012. [ Links ]

Nel L & Van der Westhuyzen C 2009. Conducting transitional strategies that support children with special needs in assuming adult roles. In I Söderback (ed). International handbook of occupational therapy interventions. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75424-6_42 [ Links ]

Raghavan R, Pawson N & Small N 2013. Family carers' perspectives on post-school transition of young people with intellectual disabilities with special reference to ethnicity. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(10):936-946. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01588.x [ Links ]

Rapanaro C, Bartu A & Lee AH 2008. Perceived benefits and negative impact of challenges encountered in caring for young adults with intellectual disabilities in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(1):34-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00367.x [ Links ]

Sandelowski M 2000. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4):334-340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4%3C334::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-G [ Links ]

Seidman I 2006. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (3rd ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Shaw L & Rudman DL 2009. Guest editorial: Using occupational science to study occupational transitions in the realm of work: From micro to macro levels. Work, 32(4):361-364. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0848 [ Links ]

Smart M 2004. Transition planning and the needs of young people and their carers: The alumni project. British Journal of Special Education, 31(3):128-137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00343.x [ Links ]

Stewart D 2013. Transitions to adulthood for youth with disabilities through an occupational therapy lens. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. [ Links ]

Vlachos CJ 2008. Developing and managing a vocational training and transition planning programme for intellectually disabled learners. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/709/thesis.pdf7sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 6 April 2020. [ Links ]

Ward L, Mallett R, Heslop P & Simons K 2003. Transition planning: How well does it work for young people with learning disabilities and their families? British Journal of Special Education, 30(3):132-137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00298 [ Links ]

Winn S & Hay I 2009. Transition from school for youths with a disability: Issues and challenges. Disability & Society, 24(1):103-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802535725 [ Links ]

World Federation of Occupational Therapists 2012. About occupational therapy. Available at https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy. Accessed 7 September 2020. [ Links ]

Received: 21 November 2016

Revised: 21 July 2017

Accepted: 10 December 2019

Published: 31 December 2020