Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40ns2a1845

ARTICLES

Life-design counselling for survivors of family violence in resource-constrained areas

Cobus J. VenterI; Jacobus G. MareeII

IDepartment of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa cbsventer@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa kobus.maree@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to explore and assess the feasibility of counselling based on life-design principles in enhancing the career resilience of children who are exposed to family violence. The research project involved a QUALITATIVE-quantitative mode of inquiry with 6 participants chosen based on certain characteristics. Life-design-related intervention strategies, together with various (postmodern) qualitative and quantitative techniques, were used to gather data, while data analysis was done using thematic content analysis. Quantitative data were collected from parents as well as the participants before and after the intervention. Certain themes, sub-themes and sub-sub-themes that all contributed to participants' career resilience were identified. Following the intervention, findings obtained from a qualitative perspective indicated that the outcomes of the life-design-related counselling intervention were substantial. The findings showed that various narrative techniques could be used to enhance the career resilience of children exposed to family violence. Future research could assess the value of life-design counselling in enhancing the career resilience of survivors of family violence in diverse group contexts. A greater focus could be placed on the (unforeseen) external trauma that had an impact on participants' ability to (re-)construct their career-life narratives to enhance their future selves and careers.

Keywords: adaptability; career resilience; careers; children; family violence; life-design; narrative; resilience; trauma

Introduction

Family violence, as a social phenomenon, has received increased attention over the last decade, especially with regard to its effects on the family structure as a whole. Historically, most studies have focused on family violence in general, while neglecting the effects of family violence on the psychological and emotional development of the child (Asen & Fonagy, 2017; Jouriles, McDonald, Mueller & Grych, 2012; Thiara & Humphreys, 2017; Wherry, Medford & Corson, 2015). Research over the past decade (Asen & Fonagy, 2017; Jouriles et al., 2012; Thiara & Humphreys, 2017; Wherry et al., 2015) has begun to study, with an invested interest and focus, the effects of family violence on the psychological, psychosocial and educational functioning of children. To sum up literature, children's (ongoing) exposure to domestic abuse, domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV) will most likely result in their social-cognitive competencies being negatively affected. Adverse symptoms such as loneliness and sadness, anxiety and separation anxiety, fear of death, disrupted sleep patterns, nightmares, inattention and daydreaming, delayed brain growth and development, promiscuous behaviour, substance abuse, self-harming and suicide (Asen & Fonagy, 2017; Barbarin, Richter & DeWet, 2001; Department of Social Development [DSD], Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD) & United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], 2012; O'Malley, Kelly & Cheng, 2013; Renner, 2012) can all be associated with exposure to family violence.

Little research has attempted to determine the effects of family violence and IPV on the (career) resilienceiof children within the South African context. This further highlights the need for research and subsequent knowledge pertaining to family violence and the effects thereof on children's career resilience. Zolkoski and Bullock (2012), in a study on resilience in children and youth, reported that few children grow up to reach their full potential if exposed to factors such as family dissension, which can have a detrimental effect on their ability to cope with stress and handle adversity successfully in life in an attempt to support themselves. Studies indicate that children who are exposed to family violence, in some cases, tend to be more resilient than other children (Howell, 2011; Miller, Howell & Graham-Bermann, 2012). However, the majority of children who present with poor school functioning, poor behaviour and low resiliency levels tend to be children with a background of witnessing IPV (Howell, 2011; Miller et al., 2012). Research in South Africa has neither explored the impact of family violence on the child nor expanded therapeutic interventions that can increase their career resilience. The aforementioned statement confirms that South Africa has a legitimate shortcoming in knowledge and research pertaining to the effects of family violence on a child's career resilience and lacks any sound research addressing such effects through applied scientific/therapeutic intervention strategies that could potentially enhance the child's career resilience.

Career Resilience

Over the past decade, career resilience has been studied in various ways and within various fields, including psychology, medicine, nursing and entrepreneurial development (Myers, Rogers, LeCrone, Kelley & Scott, 2018). Resilience can be conceptualised as an interdependent set of virtues and/or qualities that support individuals' psychological health and positive adaptation in the midst of disorder, trauma and trauma-related symptoms (Lengelle, Van der Heijden & Meijers, 2017; Nakkula, Foster, Mannes & Bolstrom, 2010; Ungar, 2011, 2013). Career resilience can therefore be viewed as a personality trait or construct that enables individuals to prosper despite challenging environmental factors that cause career disruptions, and it supports them to find a new "self' that is more capable of navigating the current situation (Abu-Tineh, 2011; Bimrose & Hearne, 2012; Pouyaud, Cohen-Scali, Robinet & Sintes, 2017).

Recent research suggests that we are currently finding ourselves in "liquid societies" where individuals have to manage their careers in an environment that offers less and less stable employment conditions, and where they are required to adapt to this change in the career market (Rossier, Ginevra, Bollmann & Nota, 2017). Hartung and Cadaret (2017) write that careers in the 21st century are no longer stable, and this situation requires individuals to be adaptable and resilient in order to "remain productive, purposeful, and gainfully employed" (p. 12). Although the concept of career resilience can be complex, especially when defining it from a personal as well as a corporate point of view, research indicates that career resilience is needed to enable individuals to successfully cope with and adapt to the changing vocational environment

(Mishra & McDonald, 2017; Waddell, Spalding,

Canizares, Navarro, Connell, Jancar, Stinson & Victor, 2015). Career resilience supports individuals when they take action to maintain a high level of performance while dealing with failures, professional disappointments and changing circumstances or work environments (Pouyaud et al., 2017). Recent research tends to agree with this viewpoint and expands on it, stating that career resilience is made up of three subdomains: self-efficacy; risk taking; and dependency (Lyons, Schweiter & Ng, 2015; Mishra & McDonald, 2017). Individuals who display all of these traits in their careers are more likely to be career resilient than individuals who do not exhibit them (Mishra & McDonald, 2017). Focusing on career resilience can potentially provide us with a better understanding of how individuals can thrive despite distressing circumstances. It could also provide us with an opportunity to enhance resilience in those who are experiencing trauma (i.e. family violence) and ultimately enhance career resilience in these survivors of trauma.

Life-Design Framework

When career development is proposed, it should be acknowledged that continual reflections between the self and the environment are imperative to ensure that careers are constructed in a meaningful manner (Savickas, Nota, Rossier, Dauwalder, Duarte, Guichard, Soresi, Van Esbroeck & Van Vianen, 2009). Life-design counselling emphasises the social environment, interactions and experiences that individuals construct and derive meaning from (Cardoso, Silva, Gonçalves & Duarte, 2014). Life-design counselling views life as continuous and supports individuals in negotiating the uncertainties of various transitions in life (Cardoso, Duarte, Gaspar, Bernardo, Janeiro & Santos, 2016; Savickas, 2015). In essence, the lifedesign paradigm can be seen as an intervention strategy that combines career construction and self-construction (Di Fabio & Maree, 2012), and it can be characterised as a process that is lifelong, holistic, contextual and preventative (Di Fabio & Maree, 2013; Savickas et al., 2009). The life-design framework can ultimately be viewed as a new paradigm that supports individuals to construct their careers by exploring their dominant life narratives in relation to their broader life stories (Maree, 2013), allowing individuals to construct future (career) narratives with the help of counsellors (Watson & McMahon, 2015).

Both Maree (2013) and Savickas et al. (2009) refer to life design as a paradigm that focuses on an individual's adaptability, narratability, activity and intentionality. It allows individuals to be adaptable, flexible and resilient, as they construct both their sense of self and their careers within a postmodern society that is characterised by continual changes in the workplace. Life-design counselling subsequently emphasises narratives that individuals construct for their lives, as this creates meaning (Cardoso, Janeiro & Duarte, 2018).

Family Violence

Despite various forms of legislation, domestic violenceii still increases on a yearly basis, with children either witnessing or being the victims of family violence. In many cases, these children grow up to be the alleged perpetrators of family violence and/or IPV (Pretorius, Mbokazi, Hlaise & Jacklin, 2012). IPV can be defined as the violence between two parents or caregivers, and according to numerous researchers (MacMillan, Wathen, & Varcoe, 2013; Mahenge, Stöckl, Mizinduko, Mazalale & Jahn, 2018), children who hear, witness and/or personally experience such incidents suffer trauma that can be classified as part of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). A recent study on the needs of children exposed to domestic violence found that in most cases where family violence is present, children are the unnoticed or silent victims (Clarke & Wydall, 2013). Studies show that children who live in a home environment characterised by familial violence are more likely to experience physical abuse themselves than children who are not exposed to such an environment. They are also more likely to exhibit "attention bias"iii (Briggs-Gowan, Pollak, Grasso, Voss, Mian, Zobel, McCarthy, Wakschlag & Pine, 2015:1194; Clarke & Wydall, 2013).

A positive correlation has been found between the level of family violence and children's resiliency levels, which supports the theory that factors such as parenting ability and effectiveness, as well as the mental health of parents, play a role in the degree of resilience that individuals develop to effectively handle IPV and domestic violence (Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell & Girz, 2009; Khodarahimi, 2014). IPV and domestic violence negatively influence an individual's ability to construct a resilient life and research has shown that children who are chronically exposed to such circumstances (which are typically associated with families in resource-constrained settings), often turn to street life due to familial conflict and abject poverty (Embleton, Mwangi, Vreeman, Ayuku & Braitstein, 2013). Research by McFarlane, Symes, Binder, Maddoux and Paulson (2014) indicates that the effects of family violence can transfer to subsequent generations (i.e. have an intergenerational impact), which means that children who are affected by family violence run a high risk of experiencing growth and developmental delays as well as dysfunctional behaviour.

Goal of the Study

The purpose of this study was to explore and assess the feasibility of counselling based on life-design principles in enhancing the career resilience of children who are exposed to family violence in resource-constrained settings.iv The following (exploratory) questions guided the research:

• How did the survivors of family violence in this study experience life-design-based counselling?

• How did the intervention influence participants' career resilience?

Method

Research Design

Nonexperimental implementation research was conducted, using a QUALITATIVE-quantitative mode of inquiry. Six intrinsic case studies were conducted, embedded in an intervention framework (uppercase denotes the priority given to qualitative data). This study utilised non-probability, stratified purposive sampling with six participants chosen based on certain characteristics which allowed engagement with the research questions and interaction with the dominant themes. All participants were referred to the researcher by a local non-profit organisation (NPO), all adhering to the required characteristics as delineated next. Participants had to be 1) between the ages of 9 and 13 years; 2) primary school learners; 3) experienced family violence (current or past violence); and 4) willing to engage with the process of life-design-related counselling. The duration of the study for all participants was 10 weeks with some participants extending the intervention process by one week.

Data Gathering

For this research project both quantitative and qualitative data were collected in an attempt to better understand the unspoken challenges of the phenomenon being studied (Jackson, 2015). Qualitative data collection was done as part of the life-design-related counsellingv and included the following techniques, namely, interviews, conversations, observations and educational-psychological interventions. Quantitative data were collected before and after the life-design-related intervention from both parent(s) and participant(s). The quantitative measures that were utilised are as follows: The Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA) (Prince-Embury, 2008), The McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Ryan, Epstein, Keitner, Miller & Bishop, 2005), The McMaster Clinical Rating Scale (MCRS) (Ryan et al., 2005), and the McMaster Structured Interview of Family Functioning (McSiff) (Ryan et al., 2005).

Data Analysis

Data analysis in this study was achieved through thematic content analysis, which can be best described as a process that highlights certain themes giving meaning to, or "voicing", the reality of participants (Braun & Clarke, 2006:80). Thematic analysis can be seen as a type of narrative analysis in which the researcher attempts to uncover commonalities or emerging themes that run through the experiences of individuals (Maree, 2016). During the process of identifying themes in the qualitative data, the primary scales of the RSCAvi(sense of mastery, sense of relatedness, and emotional reactivity) were first implemented deductively as a priori themes. An attempt was also made to identify new themes, sub-themes and sub-sub-themes as thematic analysis was implemented, working towards a richer and more comprehensive description of the data gathered. In an attempt to provide structure and trustworthiness to the identified and documented themes, the following six steps of thematic analysis (as delineated by Braun & Clarke, 2006) were executed: 1) become familiar with the data; 2) generate initial codes; 3) search for themes; 4) review themes; 5) define themes; and 6) write-up or producing the report.

Ethical Issues

To ensure that the proposed study was ethically sound, informed assent was obtained after informing all participants of the nature of the study. Throughout the study confidentiality and anonymity remained intact, as well as through the process of communicating the findings. Care was taken to ensure that all participants were protected from any harm; and the voluntary nature of participation was discussed with all participants, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. The study, along with all the quantitative and qualitative intervention strategies, was administered by a registered educational psychologist to ensure the correct implementation and interpretation of the techniques, strategies and data.

Throughout the study an attempt was made to maintain the trustworthiness of results by means of a thorough audit trail, reflective journals, observation notes, and detailed and continuous feedback discussions between the main researcher (first author) and the supervisor (second author) . Maree (2012) contends that the concept of trustworthiness in qualitative research has both internal and external validity. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pretoria.

Findings

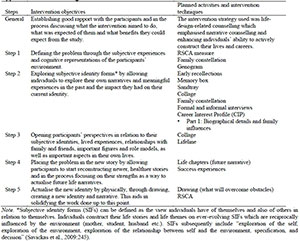

The following table gives an indication of the relevant themes, sub-themes and sub-sub-themes that emerged during the deductive-inductive process.

Below, verbatim responses are provided (where applicable) to promote and substantiate participants' sub-themes.

Sense of Mastery Brief description

The sense of mastery scale comprises three sub-themes - optimism, self-efficacy and adaptability -all of which contribute to individuals' ability to engage in effective problem solving, enhance their self-efficacy and master their environment (Prince-Embury, 2015).

Optimism

Currently I am in a good space in my life. I have clothes, food, a roof over my head, and friends. I still fight but I don't fight as much as I use too. I don't use my fists as much anymore but talk more. (2, 6, 20, 648-653).vii

Self-efficacy

In the future I see myself as a policeman, with a good job, children, and a house (3, 3, 11, 403).

Adaptability

Overall I don't talk negatively to myself. Whenever I try and don't do something correct then I will just try again until I get it right (4, 8, 31, 1,035-1,039).

Sense of Relatedness

Brief description: This scale contributes to the degree of a person's ability to relate to other individuals, thus increasing the quality of their relationships and their sense of relatedness (Prince-Embury, 2007).

Sense of trust

My mother will never disappoint me. She always comes on my birthday and brings me presents (3, 1, 5, 175-176).

Perceived access to support

My grandmother and grandfather mean a lot to me. They make sure we have food, help us with homework, and make sure we go to school (3, 3, 9, 314-315).

Comfort with others

I really like my grandmother and grandfather. I also like my family. They are there when you need them, they buy you clothes and look after you. They also help me to be a good person (5, 3, 12, 380).

Tolerance of differences

My father forgot to congratulate my brother on his birthday which hurt him really bad. I phoned my father and told him what he did was mean and I am really cross at him (4, 2, 9, 308-311).

Emotional Reactivity

Brief description: The emotional reactivity scale comprises three sub-themes - sensitivity, impairment and recovery - all of which play a part in an individual's emotional reactivity and ultimate levels of resilience (Prince-Embury, 2007).

Sensitivity

When my parents fight it makes me angry because I don't want them to fight in front of my sister (6, 1, 7, 231).

Recovery

I am still angry when I think of what my father did to my brother. That was more than a week ago but when I think of him, I still get angry (4, 4, 19, 618619).

Impairment

I don't think I can ever be a good person again (6, 3, 22, 734).

Inductively Identified Themes

Problem solving

When my sister and I get angry at one another we sort it out. We sit and talk to one another and we would play (3, 1, 3, 78-79).

Communication

Grandmother and I had a discussion and she said that I need to start listening to them and start obeying them, especially when they ask me to do something (1, 9, 18, 591).

Roles

At this stage my mother is not staying with us but we don't hold that against her as she needs to work otherwise, she would not be able to support us. At least she sends money to my grandmother to buy bread and milk. (3, 3, 12, 421-423)

Affective responsiveness

When my stepfather wants to hurt my mother, I will stand up and protect her because I care about her and I love her (2, 1, 4, 1,198-1,200).

Affective involvement

I helped my brother with washing some stuff at home since he doesn't like it. I enjoy helping my brother because I feel good afterwards and I like to help my brother (1, 8, 10, 335-336).

Behaviour control

Nobody disciplines me when I don't listen to my mother or grandmother. I just go and say sorry afterwards (2, 1, 8, 241-242).

Inductively Identified Sub-Themes Manifestations of the influence of an enhanced sense of self

When people make me angry, I helped myself to change. I just tell myself to keep quiet and walk away. This way I don't get angry (1, 8, 12, 380381).

Increased awareness of changing cognitive processes

Yes. I can remind myself of all the good things and the fact that I want to be a better person. I can also keep on telling myself that I don't want to hit people anymore (3, 7, 23, 867-868).

Enhanced future perspectives

My dream is to live in a big house with my mother, grandmother, grandfather, and my brothers. I would like to be like my mother except that I wouldn't want to work in a pub. I want to be a doctor one day. (4, 3, 13, 410-412)

Identification of strengths and weaknesses

I can study hard to get somewhere in life. This is something I can do by myself (3, 6, 21, 760).

Emotional awareness

When the adults fight and I see it then it makes me angry and I then want to fight as well (3, 1, 3, 108).

Expressions of personal growth

If I want to reach my dream then it is important that I keep on studying. I also need to change my behaviour like I can't hit other children or use foul language (1, 7, 9, 284-285).

Incomplete cognitive processing

No. I know there are other things I would like to do but I haven't thought about it (2, 5, 17, 562).

Unwillingness to forgive

When he hurts my mother, I want to assault him. I still want to but he keeps on closing his door (1, 5, 6, 181).

Anxiety

Sad. We are used to them fighting but regardless I still get scared and I worry about my mother. It is not nice to see them fight like that (1, 5, 5, 168169).

Appreciation of kinship relationships

... love you grandfather. You are the only grandfather that I love at this moment and grandmother is the only grandmother whom I love (4, 3, 10, 333-334).

Feelings of being accepted

My mother, grandfather, and uncle. They constantly tell me that they are proud of me (4, 8, 30, 1,000).

Inadequate relationships between children and biological parents

I don't talk to my father that much anymore. When I do Skype them I will mostly talk with my oldest brother, Aunt Kitty, and my stepmother. I am still angry at him (4, 3, 11, 373-374).

Appreciation of social interactions

... I gave this one boy a piece of bread to help him. It felt like Jesus was in my heart. We are now best friends and he is my only best friend (5, 2, 8, 255256).

Inductively Identified Sub-Sub-Themes

Conditional forgiveness

If I forget about all the bad things that happened and start thinking about all the good things that happened. Like I can forgive my father and move forward in life (3, 3, 9, 336-337).

Work ethic

To go forward means that I am going to work hard, study hard, do my homework, work in class and listen to my teachers (3, 3, 10, 339-340).

Values

I feel good when I help people. That is why I am no longer going to bully other children (2, 9, 26, 847).

Religious beliefs

Here is my future. God came into my heart and he told me to be a better person. He told me to look after my children, be happy, and have a good job

(5, 9, 22, 744-745).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore and assess the feasibility of counselling based on life-design principles for enhancing the career resilience of children who are exposed to family violence in resource-constrained settings. The primary research question was: What is the influence of life-design-related counselling on the career resilience of survivors of family violence in resource-constrained settings?

The secondary (exploratory) questions guided the research:

• How did the survivors of family violence in this study experience life-design-based counselling?

• How did the intervention influence participants' career resilience?

In this section, I shall review the research questions against the framework of the findings of the study. I draw on literature related to life-design-related counselling resilience, especially during adolescence, to compare my findings to previous findings. I also discuss the secondary research questions first, after which the primary research question is considered.

How Did Survivors of Family Violence in this Study Experience Life-Design-Based Counselling?

All six participants relished the opportunity to be a part of the life-design intervention, as it allowed them the opportunity to express their feelings, discuss their past traumatic experiences, gain better insight into their own behaviour, and achieve a higher sense of emotional awareness and introspection. This enabled them to start the process of constructing healthier and new identities that could help them to actualise their future career aspirations. The process furthermore allowed participants to realise what impact exposure to family violence has had/still has on their behaviour towards others and their relationships with friends and family. Most participants were able to verbalise, through the life-design counselling process, their desired future careers, but also their unpreparedness in terms of preparing for such careers. When participants were supported in this process, most of them constructed better future career trajectories and, in the process, assumed their role as social actors, motivated agents and autobiographical authors. Participants, at times, struggled to think of practical ways in which they could work towards their future career goals. It was evident that they generally lacked information about future careers and that limited discussions had taken place with parents/caregivers in relation to this topic.

How Did the Intervention Influence Participants' Career Resilience?

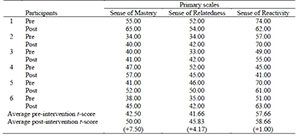

Considering participants' pre- and post-test scores, most participants improved their resiliency scale scores. They increased their scores on sense of mastery (optimism, self-efficacy and adaptability) and sense of relatedness (trust, support, comfort and tolerance), which indicates that the life-design-related intervention had a substantial effect on enhancing these core dimensions. It is evident that the processes involved in the life-design-related intervention were able to increase those intrinsic qualities in individuals that contributed to their career resilience. Not all participants indicated a positive decrease in their emotional reactivity scale (sensitivity, recovery and impairment), with only a few indicating growth in relation to the core dimensions that are directly linked to resilience. One possible explanation for this finding could be that participants had been exposed to adverse circumstances on a daily basis, which contributed to their inability to recover from continuous emotional arousal. In general, the life-design-related counselling intervention appeared to have a substantial impact on participants' resiliency scores. By enhancing the core dimensions involved in resilience, participants' career resiliency levels would be enhanced. Despite the fact that all participants were exposed to family violence throughout this study, they indicated enhanced resiliency levels, which revealed the value of the life-design-related intervention.

What is the Influence of Life-Design-Related Counselling on the Career Resilience of Survivors of Family Violence in Resource-Constrained Settings?

Family violence, as a vertical stressor, influenced the way participants perceived themselves and dictated the shaping not only of their individual identity, but also the family's perceived shared identity. This, coupled with limited socioeconomic resources, increased the negative effects of family violence on participants. Those who experienced family violence were unable to access the necessary psychological, emotional and social support to help them deal effectively with the psychological impact of family violence. In essence, my study supported existing research (Asen & Fonagy, 2017; Barbarin et al., 2001; DSD et al., 2012; O'Malley et al., 2013; Renner, 2012) delineating the impact of family violence on its victims. The study furthermore indicated that one can expect to find the same negative consequences for individuals exposed to family violence in the South African context as can be found in international literature. Through the life-design-related counselling intervention, participants were able to engage with their social environment in a process of meaning making, especially with regard to their traumatic experiences related to family violence. Participants were given the opportunity to verbalise their experiences and, in the process, become aware of the impact of these experiences, not only on their personal development but also on their interactions with the people around them. The life-design-related counselling intervention allowed participants to construct new, healthier identities and in the process rescript their future life stories. By engaging in the process of actualising new identities and constructing future careers, participants were able to enhance certain aspects and constructs of (career) resilience within individuals, which means that they grew throughout the process and were able to give expression to their authentic selves. Participants exhibited enhanced adaptability and narratability, which was apparent in the manner they approached the construction of future careers and the rescripting of new identities.

Relating Our Findings to the Available Literature on the Topic

By comparing deductive a priori themes with existing literature, I observed and came to learn that the specific constructs that constitute resilience were present within participants. These constructs were not only present; participants actually reflected them in a positive manner, which suggests that the qualities involved may have been enhanced by the life-design-related intervention. Participants in general exhibited enhanced levels of mastery and relatedness which, according to Prince-Embury (2007, 2008), indicates individuals' ability to engage in effective problem solving, enhance their self-efficacy, master their environment and relate to other individuals, thus increasing the quality of their relationships and their sense of relatedness. A decrease was noted in participants' emotional reactivity after they had engaged with the life-design-related intervention that indicates no improvement in individuals' ability to regulate the "speed and intensity of negative emotions" when faced with adversity (Prince-Embury, 2015:59). The inability to successfully regulate emotional states, with consequent negative emotional reactivity, has been linked to both psychological and physical health problems (Feldman, Lavallee, Gildawie & Greeson, 2016).

Inductively identified additional themes allowed us to explore further the concept of resilience and allowed us to identify different themes that formed part of the participants' lives. Themes related positively to those identified in the McMaster Model of Family Functioning (MMFF) (Ryan et al., 2005) and reflected the manner in which these families' daily functioning influenced participants' resilience. Participants in this study presented with behaviours such as stress, anxiety, depression, difficulty with emotional regulation, lack of adaptability, and conduct problems. This finding generally supports the findings of previous research by others and suggests that these behaviours are a direct result of participants' exposure to family violence (Acuna & Kataoka, 2017; Carr & Kellas, 2018; Gugliandolo, Costa, Cuzzocrea & Larcan, 2015; Li, Eschenauer & Persaud, 2018; Wang & Kenny, 2014). Inductively identified sub-themes and sub-sub-themes (as listed in Table 1) all provided evidence of the various "symptoms" associated with individuals who are exposed to chronic IPV and/or domestic violence. Part of the life-design-related counselling approach involves counsellors serving as a reflective audience and aiding individuals to become mindful of their emotions, thoughts and feelings - an aspect that is central to career construction (Del Corso, 2017), as well as to this study.

The research furthermore provided evidence, albeit extremely limited, of the effectiveness of life-design-related counselling interventions to enhance resilience and contribute to existing research. The life-design-related counselling process enhanced certain aspects of resiliency in participants, and in the literature discussion it was shown to have a long-term impact. However, the harmful long-term impact of domestic violence on participants' resilience was also highlighted in the literature discussion and emphasised the importance of minimising the negative external variables. The sample consisted of a small number of participants living in a specific socioeconomic environment and within a specific cultural and educational context. The results can therefore not be generalised to the wider population. Numerous unanticipated variables that had not been accounted for had an impact on the lives of participants. These unanticipated variables included parent(s) losing their jobs; the alleged perpetrator (aggressive and/or abusive parent) returning to the home environment; loss of family members; crime; and the diagnosis of terminal illness among family members. Some participants experienced additional trauma and adverse experiences that had an effect on their emotional well-being and possibly their resiliency levels.

Advice to Others Who May Wish to Conduct This Type of Intervention and Analysis The first aspect relates to the specific activities that were chosen as part of the life-design-related intervention. Some participants struggled with these activities, which made it difficult for them to engage fully with the process. Introducing different activities could have supported us in obtaining even richer data, especially from the younger participants. This could have enhanced the trustworthiness of the results. Likewise, the parents/caregivers could have been involved in the life-design-related counselling intervention, largely because their continual involvement could have enhanced the emotional and psychological growth that took place within participants. Moreover, administering the RSCA questionnaire again six to 12 months after the study has been completed could be considered to assess the longer-term impact of the research. In addition, using alternative questionnaires to establish whether the increase in resiliency scores was still present in participants after this period could be considered. In future, more attention should also be given to the allocated period, ensuring that participants are able to complete the tasks in the life-design-related intervention. More time should be provided to allow participants to consult more methodically with family members and peers. If they had more time, participants would be able to critically reflect on the sessions and engage in better planning for the next session(s).

Recommendations for Future Research The following aspects can be considered for future research. Firstly, future life-design-related interventions should consider constructing their interventions according to the same guiding principles applied in the current research. This would allow the researcher to explore participants' core dimensions (related to resilience) that have a direct impact on career resilience, and how these individuals potentially recover from adverse circumstances. Secondly, participants should always be given the opportunity to engage in the life-design-related intervention in their own mother tongue and with a facilitator that they feel comfortable with. Ensuring that these aspects are present could potentially enhance the efficacy of the life-design-related intervention. Thirdly, participants' socioeconomic backgrounds and cultural identities should always be taken into consideration when planning the specific life-design-related counselling activities. Fourthly, activities should be created in such a way that they can be used with participants of various ages and in various developmental phases. Younger participants could find it challenging to engage in activities that are not appropriate for their developmental phase and/or cognitive functioning level. Adapting activities to different ages would allow for the gathering of more trustworthy and valid data. Fifthly, future research could explore the roles teachers may fulfil in ensuring that the work done as part of the life-design-related intervention is continued in a way that facilitates more effective career transitions. Finally, all potential external variables influencing participants' career resilience should be taken into consideration and be addressed in the planning phase of the research study.

Conclusion

The value of intervening by means of life-design-related counselling in the lives of children who are experiencing family violence has been enormous. Providing this intervention meant that the individuals were helped to effectively construct successful future career trajectories. Overall, the findings suggest that the intervention managed to enhance participants' career resilience, thus supporting them to construct better future life and career trajectories. I believe that this intervention could be introduced as part of the school curriculum in an effort to introduce more individuals to this process and the value they can gain from this experience. The life-design-related counselling process helps to address the challenges faced by the South African healthcare system on how to support individuals concerned in a way that is both culturally applicable and financially viable - in the current and future social environment.

Authors' Contributions

Guided and assisted by Prof. Maree from the outset, Cobus J. Venter wrote the initial draft manuscript and provided the data for all tables included in this manuscript. Dr Venter conducted all patient interviews and also conducted all statistical analyses. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript. Prof. Maree both reviewed and contributed significantly to the writing of the manuscript at all levels.

Notes

i . We recognise that resilience as an umbrella term refers to individuals' ability to bounce back and/or maintain equilibrium in their personal lives. Career resilience implies much the same with the focus being on the career environment and the adversities that individuals face throughout their careers. Resilience and career resilience refer, in most ways, to the same intrinsic values and constructs, and this matter was acknowledged throughout the study.

ii . Domestic violence can be defined as the violence between two parents or caregivers evident in the taxonomy by Holden (2003:152) which "outlines specific types of exposure, each falling into one of the four broad dimensions of prenatal exposure (i.e. real effects on the foetus or mother's perception that the prenatal IPV had effects on their foetus), direct involvement (i.e. child intervenes, participates in, or is victimized during the incident), direct eyewitness (i.e. child observes the incident), and indirect exposure (i.e. child overhears the incident, observes initial effects, experiences the aftermath, or hears about it)."

iii . Briggs-Gowan et al. (2015) explain that attention bias in the context of family violence refers to children who, because of prolonged exposure to family violence, have developed an abnormal sensitivity to any trigger or threat of violence.

iv . When considering the construct of resource-constrained settings this study took into consideration additional dimensions of the socioeconomic status (SES) of a family, for example access to valued resources (food, medicine, psychological services, housing); family resources (employment, satisfaction of basic needs, poverty-related resources); and caregiver strain (the stress and anxiety parents experience while taking care of children, especially children with special needs) (Munsell, Kilmer, Vishnevsky, Cook & Markley, 2016). A family's SES should therefore not be considered only in terms of their material possessions (or lack of), but should rather contemplate the resources that they have and how these resources supplement one another or work together to ensure that the family is able to function effectively in life.

v . For a more extensive description of the life-design-related counselling intervention please refer to Appendix A.

vi . The pre and post RSCA scores have been added as Appendix B.

vii . A four-digit coding system was applied where the first number referred to the participant, the second number referred to the type of life-design-related counselling intervention, the third number referred to the page number and the fourth number referred to the line(s) where the responses could be found.

viii . Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abu-Tineh AM 2011. Exploring the relationship between organizational learning and career resilience among faculty members at Qatar University. International Journal of Educational Management, 25(6):635-650. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541111159095 [ Links ]

Acuna MA & Kataoka S 2017. Family communication styles and resilience among adolescents. Social Work, 62(3):261-269. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx017 [ Links ]

Asen E & Fonagy P 2017. Mentalizing family violence Part 1: Conceptual framework. Family Process, 56(1):6-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12261 [ Links ]

Barbarin OA, Richter L & DeWet T 2001. Exposure to violence, coping resources, and psychological adjustment of South African children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(1):16-25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.16 [ Links ]

Bimrose J & Hearne L 2012. Resilience and career adaptability: Qualitative studies of adult career counseling. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3):338-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2012.08.002 [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Briggs-Gowan MJ, Pollak SD, Grasso D, Voss J, Mian ND, Zobel E, McCarthy KJ, Wakschlag LS & Pine DS 2015. Attention bias and anxiety in young children exposed to family violence. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(11): 11941201. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12397 [ Links ]

Cardoso P, Duarte ME, Gaspar R, Bernardo F, Janeiro IN & Santos G 2016. Life Design Counseling: A study on client's operations for meaning construction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 97:13-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2016.07.007 [ Links ]

Cardoso P, Janeiro IN & Duarte ME 2018. Life design counseling group intervention with Portuguese adolescents: A process and outcome study. Journal of Career Development, 45(2):183-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316687668 [ Links ]

Cardoso P, Silva JR, Gonçalves MM & Duarte ME 2014. Narrative innovation in life design counseling: The case of Ryan. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3):276-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.001C [ Links ]

arr K & Kellas JK 2018. The role of family and marital communication in developing resilience to family-of-origin adversity. Journal of Family Communication, 18(1):68-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2017.1369415 [ Links ]

Clarke A & Wydall S 2013. 'Making safe': A coordinated community response to empowering victims and tackling perpetrators of domestic violence. Social Policy and Society, 12(3):393-406. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474641200070X [ Links ]

Del Corso JJ 2017. Counselling young adults to become career adaptable and career resilient. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Di Fabio A & Maree JG 2012. Group-based Life Design Counseling in an Italian context. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1): 100-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2011.06.001 [ Links ]

Di Fabio A & Maree JG (eds.) 2013. Psychology of career counseling: New challenges for a new era. New York, NY: Nova. [ Links ]

DSD, DWCPD & UNICEF 2012. Violence against children in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Authors. Available at http://www.cjcp.org.za/uploads/2/7/8/4/27845461/vac_final_summary_low_res.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2018. [ Links ]

Embleton L, Mwangi A, Vreeman R, Ayuku P & Braitstein P 2013. The epidemiology of substance use among street children in resource-constrained settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 108(10):1722-1733. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12252 [ Links ]

Feldman G, Lavallee J, Gildawie K & Greeson JM 2016. Dispositional mindfulness uncouples physiological and emotional reactivity to a laboratory stressor and emotional reactivity to executive functioning lapses in daily life. Mindfulness, 7:527-541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0487-3 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann SA, Gruber G, Howell KH & Girz L 2009. Factors discriminating among profiles of resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(9):648-660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.01.002 [ Links ]

Gugliandolo MC, Costa S, Cuzzocrea F & Larcan R 2015. Trait emotional intelligence as mediator between psychological control and behaviour problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24:2290-2300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0032-3 [ Links ]

Hartung PJ & Cadaret MC 2017. Career adaptability: Changing self and situation for satisfaction and success. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Holden GW 2003. Children exposed to domestic violence and child abuse: Terminology and taxonomy. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6:151-160. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024906315255 [ Links ]

Howell KH 2011. Resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to family violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(6):562-569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.001 [ Links ]

Jackson MR 2015. Resistance to qual/quant parity: Why the "paradigm" discussion can't be avoided. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2):181 -198. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000031 [ Links ]

Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Mueller V & Grych JH 2012. Youth experiences of family violence and teen dating violence perpetration: Cognitive and emotional mediators. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15:58-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0102-7 [ Links ]

Khodarahimi S 2014. The role of family violence on mental health and hopefulness in an Iranian adolescents sample. Journal of Family Violence, 29:259-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9587-4 [ Links ]

Lengelle R, Van der Heijden BIJM & Meijers F 2017. The foundations of career resilience. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-669540 [ Links ]

Li MH, Eschenauer R & Persaud V 2018. Between avoidance and problem solving: Resilience, self-efficacy, and social support seeking. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(2):132-143. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12187 [ Links ]

Lyons ST, Schweiter L & Ng ESW 2015. Resilience in the modern career. Career Development International, 20(4):363-383. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-02-2015-0024 [ Links ]

MacMillan HL, Wathen CN & Varcoe CM 2013. Intimate partner violence in the family: Considerations for children's safety. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12):1186-1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.005 [ Links ]

Mahenge B, Stöckl H, Mizinduko M, Mazalale J & Jahn A 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence during pregnancy and their association to postpartum depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229:159-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjad.2017.12.036 [ Links ]

Maree JG (ed.) 2012. Complete your thesis or dissertation successfully: Practical guidelines. Claremont, South Africa: Juta and Company Ltd. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2013. Counselling for career construction. Connecting life themes to construct life portraits. Turning pain into hope. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense. [ Links ]

Maree K (ed.) 2016. First steps in research (2nd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

McFarlane J, Symes L, Binder BK, Maddoux J & Paulson R 2014. Maternal-child dyads of functioning: The intergenerational impact of violence against women on children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18:2236-2243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1473-4 [ Links ]

Miller LE, Howell KH & Graham-Bermann SA 2012. Potential mediators of adjustment for preschool children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(9):671-675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.005 [ Links ]

Mishra P & McDonald K 2017. Career resilience: An integrated review of the empirical literature. Human Resource Development Review, 16(3):207-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484317719622 [ Links ]

Munsell EP, Kilmer RP, Vishnevsky T, Cook JR & Markley LM 2016. Practical disadvantage, socioeconomic status, and psychological well- being within families of children with severe emotional disturbance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25:2832-2842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0449-y [ Links ]

Myers DR, Rogers R, LeCrone HH, Kelley K & Scott JH 2018. Work life stress and career resilience of licensed nursing facility administrators. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(4):435-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816665207 [ Links ]

Nakkula MJ, Foster KC, Mannes M & Bolstrom S 2010. Building healthy communities for positive youth development. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5744-3 [ Links ]

O'Malley DM, Kelly PJ & Cheng AL 2013. Family violence assessment practices of paediatric ED nurses and physicians. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 39(3):273-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjen.2012.05.028 [ Links ]

Pouyaud J, Cohen-Scali V, Robinet ML & Sintes L 2017. Life and career design dialogues and resilience. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-669540 [ Links ]

Pretorius D, Mbokazi AJ, Hlaise KK & Jacklin L 2012. Child abuse: Guidelines and applications for primary healthcare practitioners. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Prince-Embury S 2007. Resiliency scales for children and adolescents: A profile of personal strengths. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. [ Links ]

Prince-Embury S 2008. The resiliency scales for children and adolescents, psychological symptoms, and clinical status in adolescents. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 23(1):41-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573508316592 [ Links ]

Prince-Embury S 2015. Assessing personal resiliency in school settings: The resiliency scales for children and adolescents. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 25(1):55-65. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2014.22 [ Links ]

Renner LM 2012. Single types of family violence victimization and externalizing behaviors among children and adolescents. Journal of Family Violence, 27:177-186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-012-9421-9 [ Links ]

Rossier J, Ginevra MC, Bollmann G & Nota L 2017. The importance of career adaptability, career resilience, and employability in designing a successful life. In K Maree (ed). Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0 [ Links ]

Ryan CE, Epstein NB, Keitner GI, Miller IW & Bishop DS 2005. Evaluating and treating families: The McMaster approach. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Savickas ML 2015. Life designing with adults - developmental individualization using biographical bricolage. In L Nota & J Rossier (eds). Handbook of life design: From practice to theory and from theory to practice. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1027/00447-000 [ Links ]

Savickas ML, Nota L, Rossier J, Dauwalder JP, Duarte ME, Guichard J, Soresi S, Van Esbroeck R & Van Vianen AEM 2009. Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3):239-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjvb.2009.04.004 [ Links ]

Thiara RK & Humphreys C 2017. Absent presence: The ongoing impact of men's violence on the mother-child relationship. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1):137-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12210 [ Links ]

Ungar M 2011. Community resilience for youth and families: Facilitative physical and social capital in contexts of adversity. Children and Youth Social Services Review, 33(9):1742-1748. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013493520 [ Links ]

Ungar M 2013. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3):255-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805 [ Links ]

Waddell J, Spalding K, Canizares G, Navarro J, Connell M, Jancar S, Stinson J & Victor C 2015. Integrating a career planning and development program into the baccalaureate nursing curriculum: Part I. Impact on students' career resilience. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 12(1):163-173. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnes-2014-0035 [ Links ]

Wang MT & Kenny S 2014. Longitudinal links between fathers' and mothers' harsh verbal discipline and adolescents' conduct problems and depressive symptoms. Child Development, 85(3):908-923. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12143 [ Links ]

Watson M & McMahon M 2015. From narratives to action and a life design approach. In L Nota & J Rossier (eds). Handbook of life design: From practice to theory and from theory to practice. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1027/00447-000 [ Links ]

Wherry JN, Medford EA & Corson K 2015. Symptomatology of children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 8:277-285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0048-x [ Links ]

Zolkoski SM & Bullock LM 2012. Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12):2295-2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009 [ Links ]

Received: 6 May 2019

Revised: 10 December 2019

Accepted: 23 January 2020

Published: 31 December 2020

Appendix A: The Life-Design Intervention Plan

Appendix B: Pre- and Post RSCA Scores