Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1794

ARTICLES

Pre-service teachers' pedagogical development through the peer observation professional development programme

Luis Miguel Dos Santos

Woosong Language Institute, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea. luismigueldossantos@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Student-teaching internships in a teacher-preparation programme are a significant way for teachers to gain practical skills and transfer their textbook knowledge into classroom practice. One of the outcomes of student-teaching internships is that pre-service teachers can observe experienced teachers' teaching pedagogy and strategies for implementing their skills. The purpose of the research study reported on here was to explore how pre-service teachers acquire and improve their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation training model at the secondary school at which they intern, with a focus on pre-service teachers with an interest in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) teaching. The results indicate that most of the participants could learn and improve their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation professional development programme - particularly young teachers without significant work experience. More importantly, the research proved how a peer observation cycle programme may apply to different educational systems with similar structures internationally, particularly in former European colonised countries with similar backgrounds.

Keywords: peer observation cycle programme; pre-service teachers; student-teaching internship; teacher preparation programme; teachers' professional development

Introduction

As in many other countries, including a large number of post-colonial countries in Asia and Africa, the effectiveness and application of teachers' professional development and preparation programmes have been a topic in educational fields for decades. A significant number of methodologies and theories exploring both pre-service and in-service education exist as training agencies enrol individuals in order to help them improve (Dörnyei, 2005; Dos Santos, 2017; Richard, 1998).

In classrooms, teachers' professional behaviour, curricula and instruction, and teaching and learning strategies play a vital role in students' learning experiences (Zepke, Leach & Butler, 2014). In order to become qualified teachers in Kindergarten Education to 12th grade (K-12) classrooms, individuals with a secondary school diploma may complete a bachelor's degree with a focus on education, along with a student-teaching internship. Individuals with a bachelor's degree or higher may alternatively complete a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) or postgraduate teacher training with a student-teaching internship in order to achieve Qualified Teacher Status (QTS). Although South Africa does not have the QTS as described above, individuals must follow either way to achieve their initial license in teaching. Besides traditional classroom instructions communicated via textbooks, pre-service teachers must complete a student-teaching internship at a partnered school. A student-teaching internship in a teacher-preparation programme is a significant way for teachers to gain practical skills and transfer their textbook knowledge into classroom practice (Whitty, 2014). For instance, one of the assessments in a student-teaching internship is the capstone project, through which pre-service teachers identify how to transfer textbook knowledge into real classrooms with appropriate instruction and suggestions from experienced teachers and supervisors at the partnered school. Through directions from school supervisors and university programme coordinators, pre-service teachers make improvements to their own practice by observing other pre-service and in-service teachers' behaviour and classroom instruction (Dos Santos, 2016a; Wall & Hurie, 2017).

The purpose of this research study was to understand how pre-service teachers acquire and improve their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation cycle programme (Dos Santos, 2017) (hereafter referred to as POCP) at their interned secondary school(s), with a focus on pre-service teachers with interest in STEM teaching (Dos Santos, 2016b). The results of this research indicate that more than half of pre-service teachers improved their teaching pedagogy after the peer observation professional development programme, particularly young teachers without significant work experience. In this paper I provide recommendations and suggestions for internship supervisors and curriculum developers at universities, to help them improve the curriculum and student-teaching expectations, as well as the programme content and strategies that may be beneficial to career-changing teachers (i.e. teachers from the professional industry to the teaching profession) transferring rich industry and vocational experience into the K-12 classroom environment (Yuan & Lee, 2014). This study was guided by the following research questions:

1) How do pre-service teachers enrolled in a PGCE programme describe the student-teacher internship experience of the Peer Observation Cycle Programme?

2) How do teachers (senior, mid-level, and pre-service) improve their teaching pedagogies and strategies after the completion of the Peer Observation Cycle Programme?

Background

Macau Special Administrative Region (Macau SAR) is an area of multi-cultural cities located in southern China, where Eastern (primarily Chinese) and Western teaching strategies can be found in local educational institutions (Cheng, 1999; Dos Santos, 2017). Observation and evaluation are widely used in teachers' professional development programmes. Regardless of their orientation (e.g., Eastern or Western teaching practices), student-teaching internships and teaching observations offer various benefits to teachers, administrators, and even students, such as recommendations for teaching strategies and the development of confidence, to aid the management of all classroom situations (Dos Santos, 2016a, 2017). In order to receive QTS and the PGCE, career-changing teachers must complete a student-teaching internship and observation programme (Yuan & Lee, 2015). Literature provides evidence of the effectiveness of in-service teachers' teaching practice, yet there is very little research on the peer observation of pre-service career-changing teachers.

The research study reported on here took place at Chinese-language-oriented private secondary schools in Macau SAR, in order to explore how pre-service teachers acquire and improve their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation training model (Dos Santos, 2016a, 2017) at their interned secondary school(s), with a focus on career-changing and pre-service teachers with interest in STEM teaching (Dos Santos, 2018). Although we collected data from participants who were working in the private sector, all K-12 teachers must receive their QTS in order to provide teaching and services to students. Therefore, the status of public and private schooling does not make significant differences in the field of teachers' qualification and teaching qualities. It is worth noting that the POCP is one of the elements of the student-teaching internship.

The application of South African context

Although this study was conducted in Macau SAR, a former colonial city of Portugal in southern China, the applications and outcomes of this study may apply to a large number of former colonial countries in the sub-Saharan region in Africa with a similar European influential background (O'Sullivan, Wolhuter & Maarman, 2010). As a result, I categorised four benefits for South African scholars.

Firstly, like many former colonial countries and states, Macau SAR and a large number of African countries were colonies and territories of European countries. The culture, understanding, and perspective were influenced by their former European suzerainties (Mwaniki, 2012). Therefore, South African readers may find the effective points from the multi-cultural understanding and practice from this study as influences of the former European colonies and territories (i.e. Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) may impact the overall educational developments in Macau SAR and South Africa. For example, some researchers (Chisholm, 2005) argue that due to the historical perspective of South Africa, the previous National Curriculum tended to observe the European curriculum for its application in South Africa (Cross, Mungadi & Rouhani, 2002). Although the outcomes-based curriculum reform has been introduced to respond to South Africans' needs (Chisholm, 2005), the general structure and order continue to follow the former structure (Cross et al., 2002). Due to European leadership, Macau SAR and South Africa had employed the European or localised-European educational system, which may share similar practices (Muchie & Baskaran, 2013). Therefore, although the locations of Macau SAR and African countries are not similar, the educational practices are influenced by European policy (Luckett, 2016).

Secondly, I refer to the differences and similarities of the political influence and the original roots of curriculum planning. Although Macau SAR and other former colonial African countries had gained independence during the last century, the political system and legal policies had been influenced by the former suzerainty. Localised educational systems had been modified and introduced after independence (Eacott & Asuga, 2014). However, all these countries and regions could share similar foundational systems. For example, the procedure and legal factors of QTS in South Africa may have similar requirements as the European standard. A large number of normal schools and schools of education in Macau SAR and South Africa employed the European and westernised curriculum and instruction for their potential and pre-service teachers. The training system and internship protocol share a large number of similarities (Woeber, 2001). Chisholm (2015) further indicates the similarities and adaptions between the German and South African curriculum in terms of philosophy and structure. In short, although this research collected data from the Macau SAR environment, the result can reflect the European and South African educational curriculum due to the original roots of the curriculum structures and orders (Bertram, 2009).

In sum, although the study took place in Macau SAR, the city background (Bertram, 2009), training for teachers (Woeber, 2001), curriculum and instruction (Chisholm, 2015), and practices (Eacott & Asuga, 2014; Luckett, 2016) could share a large number of similarities which do not limit to their location. It may thus be beneficial to South African readers and scholars from former colonial countries to employ the POCP by Dos Santos (2017) in their school environment (Cross et al., 2002).

Theoretical Framework

Bandura's model is based on the notion of individual-centred relationship, so that individuals influence their environment and the environment influences their behaviour. Social Cognitive Theory indicates a triadic relationship (i.e. reciprocal determinism) among individuals, behaviour, and environment to describe complex learning decisions and behaviour, such as learning from observation (Bandura, 1983, 1986, 1989, 1991). Bandura (2004) indicates that the knowledge and behaviour from teachers' professional development might influence individuals' behaviour, outcome, expectations, and personal goals. It is worth noting that this theory focuses on how teachers learn by watching others. If teachers observe that their co-workers gain knowledge from participating and observing from the POCP (Dos Santos, 2017), they will seek to model the advantage and teaching strategies as the way of professional development. Bandura postulates that self-efficacy serves a role in a teacher's decision to follow their observation and model since it reflects the individual's beliefs about whether they may achieve a given level of success at a particular task (Bandura, 1997).

In short, this research was guided by the POCP (Dos Santos, 2017) with the concepts of Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1983, 1986, 1989, 1991) to answer the research questions. It is worth noting that the concepts of modelling, self-efficacy, and triadic relationship have been implemented into the POCP (Dos Santos, 2017).

Methodology

This study employed a qualitative research method to collect data. Face-to-face interviews and observations to collect and gather meaningful data took place in 2018 (Creswell, 2012; Seidman, 2013) to explore the pre- and post-peer observation professional development programme.

Site

The study context was Macau SAR, a Special Administrative Region of China and the former overseas territory of Portugal (Cheng, 1999). Macau SAR had an approximate population of 600,000 in the 2010s, with Chinese residents in the majority in the city. As of the 2017/2018 academic year, 46 secondary schools operated in the city, of which four are publicly funded secondary schools and the rest are privately funded secondary schools. A total of 12,829 students were enrolled in junior high schools, and 13,779 students were enrolled in senior high schools. The above enrolments included both traditional day schools and non-traditional students in evening schools. A total of 2,727 secondary school teachers were registered, which includes full-time and part-time teachers. These numbers do not include support staff such as librarians, reading specialists, lab technicians, counsellors, and social workers.

The research study was conducted at one of the privately funded secondary schools, as these schools represent the majority of the population in Macau SAR. As of the 2017/2018 academic year, the total enrolment number for the research site was 1,109 secondary school students with Chinese heritage and backgrounds, of which 48% were male students and 52% were female students.

Participants

A total of 20 individuals participated in the research study: 12 pre-service teachers, four mid-level teachers, and four senior-level teachers. All of these participants were STEM teachers (their native language was Chinese Cantonese), and they had completed their education by taking their undergraduate degrees and PGCE programmes at Chinese higher education institutions. All 12 pre-service teachers were career-changing teachers who had completed their undergraduate degrees with a focus on STEM. Six of the pre-service teachers were professional workers with at least ten years of work experience, while six were recent university graduates with less than two years of work experience (Dos Santos, 2017). It is worth noting that these participants were the entire population of the department. In other words, all teachers in the department participated in this research.

Data Collection and Peer Observation Cycle

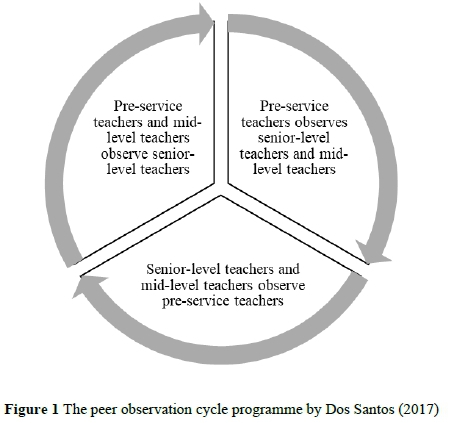

To explore how pre-service teachers acquire and improve their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation training model, this research employed the POCP, created by Dos Santos (2017). This programme focuses on teachers' professional training for in-service teachers, including junior, mid-level, and senior teachers. However, this research focused on the development for pre-service teachers. Therefore, this research replaced junior-level teachers' positions with pre-service teachers.

Observation and pre-observation cycles

According to Dos Santos (2017), three teachers were assigned to a single observation group. Firstly, pre-service teachers observed both senior and mid-level teachers. Secondly, senior and mid-level teachers observed pre-service teachers. Thirdly, pre-service and mid-level teachers observed senior teachers. The POCP is illustrated in Figure 1. The POCP serves as one training cycle or focuses on one single subject (e.g. biology). If each party believes another training cycle or another subject should be commenced, the same POCP can be followed.

Prior to the start of the POCP, I invited all the teachers to a pre-observation meeting, to clarify the steps of the POCP. During the pre-observation meeting, I explained the details and context of the observation. The teachers were encouraged to ask questions about the progress of the programme, such as the observed courses, grading rubrics, attendance, and the order of the observations.

Actual observation process

The observers' position within the classroom was planned to avoid any interruptions to the teaching. The observers were invited to sit quietly in the back corner of the classroom. The rubrics and field note worksheets were handed out to each observer for their evaluation and comments.

Post-observation sharing meeting

After the completion of the POCP, each teacher (i.e. the senior, mid-level, and pre-service teachers) was invited to a post-observation sharing meeting. The purpose of this meeting was to provide the results of the observation, to discuss the satisfaction of the rubric requirements, and to share comments from the observers' field notes, along with insights from each lecture.

Post-observation cycle interview with the researcher

To gain a deeper understanding, answer the research questions, and explore how pre-service teachers acquired and improved their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation training model, each teacher was invited to attend a semi-structured, face-to-face, one-on-one, in-depth interview. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Each teacher was invited to a follow-up interview for triangulation.

Data Analysis

An open coding strategy (Merriam, 2009) or first-level coding procedure (Saldaña, 2013) was employed in order to narrow down all the interview transcripts into first-level categories. I then continued to narrow down the categories into meaningful themes by using an axial coding strategy (Merriam, 2009) or second-level coding procedure (Saldaña, 2013). As a result, five meaningful themes were reported and used to answer the research questions (Thomas, 2006).

Protection of Human Subjects

Protecting the participants' identities, we allowed them to remain anonymous to any other employees at the study site. As the community and the industry surrounding secondary school environments in Macau SAR are relatively small, pseudonyms were assigned to protect participants' further career development after the completion of the PGCE programme (Merriam, 2009).

Interview Language Usage

As all of the participants' first language was Cantonese, they were invited to participate in the interviews in their native language. The completed themes and categories were translated into English for the purpose of reporting on them (Merriam, 2009).

Findings

Although the details of each teacher's understanding and experiences were different, similar ideas to the current research study were found. In fact, the research study mainly focused on the understanding of issues regarding pre-service teachers. However, I also interviewed and collected data from both senior and mid-level teachers in order to capture the holistic situation within the student-teaching internship procedures. The analysis of the interviews yielded three themes: teaching strategies and practices were absorbed from other peers; the belief that industry experience should be included in classroom environments; new teaching strategies were learnt, and knowledge from others was acquired.

Based on the interview transcripts and subsequent discussions, I categorised each sub-theme based on the background of the participants (pre-service teachers with little work experience [PSTLWE], pre-service teachers with significant experience [PSTSE], and in-service teachers). These categories were a result of each sub-group sharing similar understandings, experiences, and concepts during the interview sessions. In the following section I report on their understanding, based on the qualitative data.

Teaching Strategies and Practices were Absorbed from Other Peers

The POCP (Dos Santos, 2017) is widely used for teachers' professional development. This programme advocates the way in which interactions between peers can potentially motivate teachers to share their teaching experience and classroom management skills, which are not listed in textbooks. In addition, the industry expectations and real-life practices of career-changing teachers with significant work experience can be shared with other teachers, in order to improve their current practice.

Pre-service teachers with less work experience

The six pre-service teachers with less work experience reported a similar understanding after the completion of the POCP. Four of them believed that observing in-service teachers' teaching strategies and classroom management could serve as a model for them. According to PSTLWE#1:

I did not have any teaching experience before this student-teaching internship. I would not know how to manage the situation if … students sleep in the classroom. Should I punish the students or not? The best thing about this observation programme is that it provides opportunities for different teachers at the school to observe each other. I can learn a lot from my peers' practices.

In fact, secondary school teachers in Macau SAR are allowed to teach at least two subjects related to their undergraduate degree. For example, teachers with an undergraduate degree in engineering are allowed to teach mathematics and physics. PSTLWE#3 said:

… If I had not completed this Peer Observation Cycle Programme, I would not know how to teach another subject matter outside my area of expertise. My undergraduate degree is in engineering, so I can teach mathematics, physics, and chemistry. Observing chemistry teachers' classroom practices was key, as I do not have any experience with teaching chemistry.

Another participant shared his/her experience after the completion of the POCP. PSTLWE#4 was a potential teacher in the field of natural science. Based on his/her undergraduate degree, he/she is allowed to teach both geography and biology. He/she said:

Based on my university studies … I have the confidence to teach biology … However, as I would like to gain an endorsement in biology, I also want to observe teaching strategies for biology courses. The observation enabled me to understand the differences between teaching biology and geography. Some teaching strategies and activities are different. I cherished this observation programme as it provided me with extraordinary experience with regard to student-teaching internships.

Pre-service teachers with less work experience generally discussed the observations positively, as other experienced teachers assisted them in gaining skills with regard to classroom management and teaching strategies. This was particularly useful for pre-service teachers wanting to gain a second endorsement. As Weiner (2012) mentioned, pre-service teachers will benefit if their supervisors and mentors provide essential modelling and leaderships during the first few years of their teaching. The above finding echoes how Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1983, 1986, 1989, 1991) reflected the concepts of modelling with the POCP (Dos Santos, 2017).

PSTSE

Unlike the pre-service teachers with less work experience, the career-changing pre-service teachers with significant work experience expressed different understandings of and ideas about the POCP (Wilson & Deaney, 2010). None of the pre-service teachers with significant work experience advocated the effectiveness of the POCP. Most of them believed that the curricula in secondary schools could not respond to the demands of the current industry and university admission requirements. PSTSE#2 said:

Although students cannot work in the industry immediately after secondary school, a solid foundation with regard to fundamental science should be learnt during secondary school. The current curricula and teaching strategies in secondary school classrooms tend to be teacher-centred and textbook-oriented. Hands-on practice and experience are not encouraged.

Two other participants discussed the way in which teacher-centred teaching methodologies and curricula tended to focus on teacher-centred teaching strategies; students did not have the authority to put theory into practice in the classroom. PSTSE#4 said:

In chemistry classes, I believe students should go to a laboratory or at least watch a video of the chemical elements. I used to learn chemistry from textbooks and drawings more than twenty years ago. I cannot believe that, twenty years later, these teacher-centred and textbook-oriented teaching methodologies are still practiced. Now, my supervisor for the student-teaching internship continues to ask me to observe these outdated lectures.

PSTSE#5 shared similar ideas about the teacher-centred teaching methodology:

I do not mind observing others' teaching, but if you ask me to observe a teacher-centred classroom, I do not think it is beneficial. The current workplace and the industry usually do not use such teacher-centred sharing. In the current workplace, we are talking about critical thinking, brainstorming, and sharing, but the teacher-centred methodology has killed students' critical thinking.

Three other participants stated that the daily quizzes used in the classroom they were observing placed a significant amount of pressure on the students. PSTSE#1 said that, in his biology class, students viewed this methodology negatively, "although our current workplace requires a lot of testing and timed assignments … we should provide a happier secondary school environment for future students. I cannot agree with my supervisors' use of quizzes."

PSTSE#3 believed that daily or weekly quizzes did not only increase the pressure placed on students, but also increased the workload for both students and teachers:

Quizzes are good but, unlike university and students in international schools, the students in traditional teacher-centred or local schools need to take at least eight subjects per semester and at least six subjects each school day. In addition to learning, students still need to complete assignments and prepare for tests … as an industry manager, I do not want to increase the pressure placed on our future leaders.

Pre-service teachers with significant work experience generally expressed negative views with regard to their observations of other experienced teachers. Their expectations did not match their understanding of teaching and learning in secondary school education. For example, some researchers (Gan, Nang & Mu, 2018) indicate that teachers tended to employ their previous and positive experience and expectations into their classroom practice. Although their student-teaching internship offered significant experience and modelling to their teaching philosophy, teachers tended to employ their perspectives, practices, and concepts into their classroom management (Han & Yin, 2016). More importantly, all of the participants in this category stated that the curriculum could not meet the requirements or the demands of current workplaces.

In-service teachers

The eight in-service teachers believed that, after completion of the POCP, they had gained numerous benefits and upgraded their teaching strategies by observing their peers, regardless of their status and experience. Several in-service teachers stated that observing new university graduates and pre-service teachers with less work experience increased their understanding of how to interact with young people. Senior In-Service Teacher (SIST)#1 believed that some interactive activities and extracurricular games could increase students' interest in learning: "Although I have supervised countless pre-service teachers, this is the first time that several of my mentees inspired me with regard to teaching and learning. I believe this is mainly because of the Peer Observation Cycle Programme." SIST#4 also shared how the POCP allowed him/her to engage with other mid-level in-service teachers (MLISTs) and pre-service teachers:

Traditional observations for pre-service teachers mainly focus on a top-down approach, meaning that senior teachers observe pre-service teachers and mark down the grades. Pre-service teachers do not need to observe senior teachers and provide feedback about their teaching practices. Basically, I do not know how I can improve my teaching. The Peer Observation Cycle Programme allowed me to diagnose the problems with my teaching skills.

MLISTs also believed that the POCP allowed them to upgrade their teaching strategies by observing senior teachers and refresh their skills by observing pre-service teachers. Some teachers stated that their observations of senior teachers allowed them to upgrade their teaching. For example, MLIST#4 stated:

For teachers' professional development, MLISTs are observed by senior teachers and the leadership for the purpose of contract renewal, but mid-level teachers do not observe senior teachers', junior teachers', and pre-service teachers' teaching. Therefore, the Peer Observation Cycle Programme allowed me to observe others and improve myself.

Another participant stated that the teaching strategies of pre-service teachers refreshed his/her ideas about how to employ the theoretical practice in his/her classroom:

I like to follow the textbook curriculum, so I believed my students could follow the lecture easily. I was wrong. One of the pre-service teachers handed out worksheets and extra paper, which allowed students to note down the main points of the lecture. I had not thought about doing this before these observations.

In conclusion, after the completion of the POCP, all 20 participants stated that they had developed and learnt new teaching strategies and knowledge from their peers, regardless of their status and experience. It is worth noting that the mid-level and senior teachers, from the pre-service teachers' perspectives, tended to employ teacher-centred and textbook-oriented teaching strategies (Farmer, Chen, Hamm, Moates, Mehtaji, Lee & Huneke, 2016). However, the in-service teachers acquired positive teaching and learning strategies after the meetings and observations through the POCP. Therefore, all parties (not just pre-service teachers) who had participated in the observation activity gained and refreshed skills from each other.

The Belief that Industry Experience should be Included in the Classroom Environment

One of the features of the POCP is that all teachers may improve their teaching strategies during each observation (Dos Santos, 2017). Therefore, the teachers participating in the POCP could observe each other's development throughout the semester. One of the significant improvements made through the POCP is that all teachers, regardless of their status and experience, believed that using industry experience, hands-on practice, and real-world exercises would be beneficial. It is worth noting that the idea of adding industry experience came from the observations of the pre-service teachers with significant work experience.

Pre-service teachers with less work experience

Many pre-service teachers with less work experience stated that they had observed the development and progress of both PSTSE and in-service teachers, particularly with regard to teaching strategies and classroom management. All of the group members in these categories stated that in-service teachers also improved their teaching exercises and activities after they had observed the pre-service teachers' lectures. For example, PSTLWE#6 said:

Almost all STEM teachers at school need to participate in the Peer Observation Cycle Programme. Participation in the Peer Observation Cycle Programme can help pre-service teachers to meet the PGCE requirements and help in-service teachers to satisfy the requirements related to teachers' professional development hours as well. I can see that all of us are improving.

Besides the overall development of teachers, PSTLWE#4 clearly shared his/her views about how the first observation was different from the last observation during his/her student-teaching internship:

When three of us (i.e., pre-service, mid-level, and senior level teachers) completed our first cycle of the programme, we understood our backgrounds and teaching methodologies. After the third cycle, during the last cycle of observations (i.e., the fourth cycle), I could not only see myself but also the senior teacher and mid-level teacher employing some activities and games that I had employed in my lectures to motivate my students.

Many pre-service teachers in this category believed that the nature of sharing in the POCP allowed all the members in the POCP to gain new knowledge by sharing with and observing others.

PSTSE

One of the keys to STEM education is transferring textbook scientific knowledge into the industry. Unlike traditional liberal arts subjects, STEM training tends to involve vocational training. Almost all PSTSE stated that the relationships between in-service teachers were not just a case of supervisors and student-teachers; they were also peers who could exchange life experience. For example, three PSTSE stated that in-service teachers were eager for industry-oriented learning curricula. PSTSE#6 said:

After the second cycle of the programme, I had established an engaged relationship with several in-service teachers. By the end of the last cycle of the observation programme, we were learning from each other. I learnt classroom management and the management of student discipline from in-service teachers. The other in-service teachers learnt industry practices and exercises from me.

PSTSE#4 believed that MLISTs were open to learning from others and developing their teaching strategies:

Before I started the Peer Observation Cycle Programme, my expectation was that I would learn from other in-service teachers with experience. However, at the end, all of us learnt from each other, particularly several mid-level teachers. We sat together to exchange ideas. I could share my industry experience, and they could share their classroom management techniques.

From the perspective of PSTSE, all members in the programme learnt from and exchanged knowledge with each other through engaged relationships. It is worth noting that the nature of sharing allowed all members to develop trusting relationships with each other (DeNeve, Devos & Tuytens, 2015).

In-service teachers

With regard to in-service teachers' sharing, I noted that the four MLISTs advocated the benefits of the POCP, particularly the post-observation sharing meeting, and the observation steps, which involved observing and commenting on all members of the POCP, regardless of their status and experience. These MLISTs agreed that the nature of this POCP eliminated the top-down approach and the hierarchy that existed within the teacher-centred school system. Currently, senior teachers and school leadership observe and comment on the classroom practices of lower-level teachers. However, this POCP allowed all teachers to observe and make comments to each other without any limitations. For example, MLIST#1 stated:

I did not expect to be able to comment on the teaching strategies and practices of senior teachers. I felt glad that the senior teachers accepted my suggestions. Before this programme, there was no room for lower-level teachers to comment on or even observe the teaching of senior teachers.

MLIST#2 focused on how to implement different types of teaching and learning materials into his/her classroom:

An observation made by PSTSE#2 allowed me to think about how to combine real-life practice with our classroom exercises. I have never worked in the industry before; I did not know what the expectations of the industry were. I really learnt something from all the members.

In conclusion, all pre-service and in-service teachers stated that the POCP had two advantages. Firstly, the POCP allowed all teachers with different backgrounds, statuses, and experiences to share their teaching strategies and practices with others without any limitations (Weiner, 2012). Secondly, the POCP developed sharing and communication between senior-level and lower-level teachers; traditional observation programmes tended to focus on a top-down approach (DeNeve et al., 2015). As a result, all levels of teachers benefited from the completion of the POCP.

Increasing the Self-efficacy and Self-identity of Teachers

All of the pre-service teachers were career-changing teachers with at least one year of work experience. Although they were conducting coursework for the PGCE programme, none of them had any teaching experience in the K-12 education system. Therefore, the student-teaching internship served as their first experience of teaching in a real classroom.

Pre-service teachers with less work experience

Although the pre-service teachers with less work experience generally had one or two years of work experience, most of them were still exploring their career pathways. As these participants were still establishing their careers, the student-teaching internship and their participation in the POCP allowed them to establish the self-efficacy and self-identity of secondary school teachers. The following statements were shared by two participants. PSTLWE#5 stated:

Before I started this PGCE programme, I worked as a salesperson … I did not have any problem changing my career pathway to teaching. During the student-teaching internship and the Peer Observation Cycle Programme, I enjoyed my time as a secondary school teacher. During this time, I gained the self-identity of a teacher. I absolutely cherished the Peer Observation Cycle Programme. The programme allowed me to start conversations and exchange insights and comments with senior and mid-level teachers.

Pre-service teachers with less work experience usually take a student-teaching internship as a way of deciding whether or not they should stay in the teaching industry over the long term.

PSTSE

Changing a career pathway is not easy, particularly for professionals with significant years of experience in a certain field. Many PSTSE believed that the student-teaching internship and the POCP increased their self-efficacy and their self-identity with regard to being secondary school teachers. PSTSE#4 worked as an occupational safety specialist before joining the PGCE programme. During his former career, he provided training programmes to adult learners and employees about workplace safety issues. He shared the following with regard to experiencing the change from teaching adult learners to secondary school students:

I used to train adults, and now I have to educate the youth. Both positions are very meaningful, but I have to adjust my idea of the audiences. The traditional way of conducting an observation involves me observing the senior teachers' science classes and the senior teachers observing my science classes, with no interactions or bridges to connect us. The Peer Observation Cycle Programme is very useful because we are adults and we can talk to each other. I can develop the minds of teachers, as well as my own confidence.

In terms of self-identity, PSTSE#5 shared how the student-teaching internship, particularly the POCP, allowed him/her to establish a self-identity as a teacher:

I have never had experience as a teacher. The student-teaching internship has a requirement of being a student-teacher, but the Peer Observation Cycle Programme allowed me to enter the classroom and the field of teaching. I feel that I am part of the school, not just an outsider or student-teacher with the PGCE programme.

Unlike pre-service teachers with less work experience, these groups of participants tended to take student-teaching internships to establish their self-identity (Danielewicz, 2001). In conclusion, both pre-service teachers with less work experience and teachers with significant work experience stated that the student-teaching internship and the POCP provided significant opportunities to access the teaching industry and gain a deeper understanding thereof. Many participants believed that self-efficacy and self-identity had been established due to the sharing and exchange that had taken place as part of the POCP (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017).

Discussion

The purpose of this research study was to explore how pre-service teachers acquired and improved their teaching pedagogy through the peer observation training model (Dos Santos, 2017) at the secondary school(s) at which they interned. It focused on pre-service teachers with an interest in STEM teaching, particularly for teachers who received their training at former colonial countries and regions in African and Asia (Mwaniki, 2012). The results of this study indicate that most of the participants believed that the POCP had positive outcomes. It is worth noting that the study context was a multi-cultural and former colonial city where the understanding, pedagogy, and teachers' professional training curriculum and instruction were highly influenced by the European standard. Although the Asian context was conducted, South African scholars may benefit from the result of the study. In the following section I answer the research questions (Woeber, 2001).

Comments on the Student-teaching Internship Experience Through the POCP

In this study, I found that both pre-service teachers with less work experience and teachers with significant work experience took this opportunity to gain self-efficacy and self-identity as secondary school teachers, as not all of the pre-service teachers had any teaching experience prior to the student-teaching internship (Bandura, 2004; Dos Santos, 2016b).

Firstly, some pre-service teachers, particularly participants with less work experience, stated that the sharing and exchange in the POCP increased their confidence with regard to improving their own teaching strategies. Pre-service teachers with significant work experience stated that observing others' classroom teaching strategies could improve their own classroom practices, as traditional teacher-centred methodologies did not match the demands of the current workplace (Dos Santos, 2017). All of them agreed that the sharing and exchange of teaching ideas and classroom management skills might be beneficial.

Secondly, another advantage of the POCP was that the programme allowed all teachers to establish communication. Unlike the traditional top-down observation approach, the POCP invited all teachers of different statuses and backgrounds to observe each other's classroom practices. More importantly, the post-observation sharing meeting allowed all participants to share their feedback and comments after the observation. This practice not only developed cooperation between the pre-service teachers and in-service teachers, but also allowed pre-service teachers to comment on the teaching practices of in-service teachers (Forte & Flores, 2014).

Thirdly, the POCP also allowed in-service teachers to learn teaching strategies and practices from pre-service teachers. In most observation programmes, in-service teachers comment on the teaching practices of pre-service teachers but are not required to learn new teaching practices from pre-service teachers themselves (Whitty, 2014). This POCP provides opportunities for all participants to learn from each other.

How to Improve Teaching Pedagogies and Strategies after the Completion of the POCP

Firstly, all of the participants, regardless of their status and experience, stated that they had learnt new teaching practices from each other through the POCP. More importantly, several of the pre-service teachers with less work experience indicated that many of the in-service teachers had helped them to enhance their learning materials after the completion of the POCP (Stewart, 2014).

Secondly, although almost all of the pre-service teachers with significant work experience disagreed with the teaching strategies of the in- service teachers; most of them had gained an understanding of how to implement potential classroom practices with practical exercises and activities (Mena, Hennissen & Loughran, 2017).

Thirdly, it is worth noting that the sharing and exchange of ideas regarding the combination of industry expectations and materials in classroom practice are encouraged. After the completion of the POCP, all teachers had developed relationships involving peer learning, rather than student-teacher relationships.

Application to South African Context

In the South African context, school leadership and scholars could introduce and enhance improvements for their K-12 schools. First of all, although the interview data were gathered from teachers in the Macau SAR setting, South African teachers could benefit as the POCP was not merely design for teachers in Macau SAR. In fact, peer observation training programmes are of the key factors for teachers' professional development in the contemporary educational environment (Stewart, 2014). South African readers can edit and localise the element of the POCP into the most appropriate procedure for their own schools.

Secondly, a demand for change. Most of the pre-service teachers with significant work experience expressed that the teacher-centred teaching strategies were not appropriate for the contemporary classrooms in the Macau SAR context. It is worth noting that in the South African context, second-career teachers and pre-service teachers with significant work experience may express similar and different opinions about the current classroom environment. In fact, scholars indicated that the teaching strategies in the South African classroom needed to be improved immediately in order to respond to the demands of globalisation. If the South African school leadership applied the POCP into their schools, the result could uncover some problems and potential solutions from the perspectives of front-line teachers (Muchie & Baskaran, 2013).

Thirdly, professional, vocational, hands-on, and industrial experience are some key factors to learn and transfer into the society and workplace. It is worth noting that not only students should learn these demanding skills, but fellow teachers should also learn from each other (O'Sullivan et al., 2010). The POCP provides the platform for fellow teachers to exchange skills from previous life experiences regardless of their status and roles at the school. It also allows all personnel at schools to open their horizons to interdisciplinary subjects and skills at the workplace (Forte & Flores, 2014). Therefore, South African scholars may employ the POCP in the application of professional, vocational, hands-on, industrial experience sharing and exchange for their school teachers.

Last but not least, the encouragement of interdisciplinary exchange. Unlike the traditional peer observation where teachers observe each other within the same or similar subjects (e.g. English teachers observe other English teachers' teaching), the POCP encourages teachers from different departments to observe each other's teaching lessons. In fact, South Africa is a multi-industrial country where manufacturing, mining, agriculture, communications, tourism, wholesale and retail trade, finance and business services, and investment incentives are some of the major economic sectors. Both students and teachers should be prepared for the rapidly changing development in order to compete in the global economy. Therefore, the POCP allows teachers from different departments to share their understanding and feedback from their own perspective and expertise (Wall & Hurie, 2017).

Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

According to Chisholm (2005, 2015), in the push for teachers' professional development, this research reinforces the importance of considering the teachers' professional training programme (Danielewicz, 2001) through the POCP (Stewart, 2014). Based on the results, this study outlined the individual perceptions of peer observation and teachers' professional training for use by school administrators, university student-teaching supervisors, pre-service teachers, and in-service teachers (Weiner, 2012).

For my study, the POCP by Dos Santos (2017) tended to focus on the development of in-service teachers, including junior, mid-level, and senior teachers. However, as the nature of this research focused on the development of pre-service teachers within the student-teaching internship, I swopped the position of junior teachers with that of pre-service teachers from one of the PGCE programmes. The result gained positive answers and allowed me to create a new POCP - particularly for pre-service teachers and in-service teachers' professional development (Wilson & Deaney, 2010).

The limitations of this study provide opportunities for future research. Firstly, peer observation is one of the most common tools used alongside the observation of teaching - for example, material preparation, students' motivation, curriculum development, feedback, and self-efficacy (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). This study would have been strengthened by the inclusion of exchanges between participants regardless of their status and experience; however, some senior teachers and school leadership may not agree with pre-service teachers commenting on their teaching practices, particularly in school environments in the former colonial countries and regions in Africa and Asia (O'Sullivan et al., 2010).

Secondly, student-teaching supervisors in secondary schools may choose to mask evaluation reports, rubrics, and feedback from student-teachers. In the future, I will continue to employ the POCP in regions outside of Chinese environments, particularly in school environments in the former colonial countries and regions in Africa and Asia (Bertram, 2009; Chisholm, 2015). Regardless, the results of this study indicate positive feedback with regard to teachers' professional development, as all teachers involved had learnt new teaching practices (Eacott & Asuga, 2014) from other each at the peer-learning level (Wall & Hurie, 2017).

Thirdly, this study employed the behaviouristic concept of teacher development as a driver of teachers' professional development. However, a large number of alternative professional development models and theories exists (Weiner, 2012) in the field of teachers' education. Therefore, further research studies may be conducted in order to answer these concerns.

Fourthly, some missing parts of the historical background of South African and Macau SAR educational environments were concerned. As this research was one of the very first about the curriculum and teachers' professional development issues between South Africa and Macau SAR, further research studies within this field are encouraged.

Lastly, due to the limitation of a single-focus study, this research only recruited participants from one school and one single department (STEM). In future, researchers may expand the focus to a national level in order to collect data on general performance and understanding.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 4 November 2018; Revised: 5 July 2019; Accepted: 24 October 2019; Published: 31 August 2020.

References

Bandura A 1983. Temporal dynamics and decomposition of reciprocal determinism: A reply to Phillips and Orton. Psychological Review, 90(2):166-170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.90.2.166 [ Links ]

Bandura A 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Bandura A 1989. Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25(5):729-735. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729 [ Links ]

Bandura A 1991. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2):248-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L [ Links ]

Bandura A 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: WH Freeman. [ Links ]

Bandura A 2004. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2):143-164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660 [ Links ]

Bertram C 2009. Procedural and substantive knowledge: Some implications of an outcomes-based history curriculum in South Africa. Southern African Review of Education with Production, 15(1):45-62. [ Links ]

Cheng CMB 1999. Macau: A cultural Janus. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [ Links ]

Chisholm L 2005. The making of South Africa's National Curriculum Statement. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(2):193-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027042000236163 [ Links ]

Chisholm L 2015. Curriculum transition in Germany and South Africa: 1990-2010. Comparative Education, 51(3):401-418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2015.1037585 [ Links ]

Creswell J 2012. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cross M, Mungadi R & Rouhani S 2002. From policy to practice: Curriculum reform in South African education. Comparative Education, 38(2):171-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060220140566 [ Links ]

Danielewicz J 2001. Teaching selves: Identity, pedagogy, and teacher education. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

DeNeve D, Devos G & Tuytens M 2015. The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers' professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47:30-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.003 [ Links ]

Dörnyei Z 2005. The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Dos Santos LM 2016a. Foreign language teachers' professional development through peer observation programme. English Language Teaching, 9(10):39-46. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n10p39 [ Links ]

Dos Santos LM 2016b. Relationship between turnover rate and job satisfaction of foreign language teachers in Macau. Journal of Educational and Development Psychology, 6(2):125-134. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v6n2p125 [ Links ]

Dos Santos LM 2017. How do teachers make sense of peer observation professional development in an urban school. International Education Studies, 10(1):255-265. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n1p255 [ Links ]

Dos Santos LM 2018. Career decision of recent first-generation postsecondary graduates at a metropolitan region in Canada: A social cognitive career theory approach. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 64(2):141-153. Available at https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ajer/article/view/56293. Accessed 13 June 2020. [ Links ]

Eacott S & Asuga GN 2014. School leadership preparation and development in Africa: A critical insight. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(6):919-934. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214523013 [ Links ]

Farmer TW, Chen CC, Hamm JV, Moates MM, Mehtaji M, Lee D & Huneke MR 2016. Supporting teachers' management of middle school social dynamics: The scouting report process. Intervention in School and Clinic, 52(2):67-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451216636073 [ Links ]

Forte AM & Flores MA 2014. Teacher collaboration and professional development in the workplace: A study of Portuguese teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1):91-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2013.763791 [ Links ]

Gan Z, Nang H & Mu K 2018. Trainee teachers' experiences of classroom feedback practices and their motivation to learn. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(4):505-510. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1450956 [ Links ]

Han J & Yin H 2016. Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Education, 3(1):1217819. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1217819 [ Links ]

Luckett K 2016. Curriculum contestation in a post-colonial context: A view from the South. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(4):415-428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1155547 [ Links ]

Mena J, Hennissen P & Loughran J 2017. Developing pre-service teachers' professional knowledge of teaching: The influence of mentoring. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66:47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.024 [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Muchie M & Baskaran A (eds.) 2013. Innovation for sustainability African and European perspectives. Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mwaniki M 2012. Language and social justice in South Africa's higher education: Insights from a South Africa university. Language and Education, 26(3):213-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2011.629095 [ Links ]

O'Sullivan MC, Wolhuter CC & Maarman RF 2010. Comparative education in primary teacher education in Ireland and South Africa. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4):775-785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.013 [ Links ]

Richards JC 1998. Beyond training: Perspectives on language teacher education. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Saldaña J 2013. The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Seidman I 2013. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (4th ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Skaalvik EM & Skaalvik S 2017. Motivated for teaching? Associations with school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67:152-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.006 [ Links ]

Stewart C 2014. Transforming professional development to professional learning. Journal of Adult Education, 43(1):28-33. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1047338.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020. [ Links ]

Thomas DR 2006. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2):237-246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748 [ Links ]

Wall DJ & Hurie AH 2017. Post-observation conferences with bilingual pre-service teachers: Revoicing and rehearsing. Language and Education, 31(6):543-560. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1340481 [ Links ]

Weiner L 2012. The future of our schools: Teachers unions and social justice. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. [ Links ]

Whitty G 2014. Recent developments in teacher training and their consequences for the 'University Project' in education. Oxford Review of Education, 40(4):466-481. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.933007 [ Links ]

Wilson E & Deaney R 2010. Changing career and changing identity: How do teacher career changers exercise agency in identity construction? Social Psychology of Education, 13:169-183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-010-9119-x [ Links ]

Woeber C 2001. The influence of Western education on South Africa's first black autobiographers. English Studies in Africa, 44(2):57-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138390108691305 [ Links ]

Yuan R & Lee I 2014. Pre-service teachers' changing beliefs in the teaching practicum: Three cases in an EFL context. System, 44:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014/02/002 [ Links ]

Yuan R & Lee I 2015. The cognitive, social and emotional processes of teacher identity construction in a pre-service teacher education programme. Research Papers in Education, 30(4):469-491. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.932830 [ Links ]

Zepke N, Leach L & Butler P 2014. Student engagement: Students' and teachers' perceptions. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2):386-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.832160 [ Links ]