Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 no.3 Pretoria ago. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1793

ARTICLES

A professional development programme for implementing indigenous play-based pedagogy in kindergarten schools in Ghana

Felicia Elinam DzamesiI; Judy van HeerdenII

IDepartment of Basic Education, Faculty of Educational Foundations, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana. felicia.dzamesi@ucc.edu.gh

IIDepartment of Early Childhood Education, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In this article we report on the development and implementation of a professional development programme for teachers of the kindergarten curriculum (4-5 year olds) in Ghana. Kindergarten teachers in Ghana have little experience and meagre training in implementing a play-based pedagogy as recommended in the national curriculum. An indigenous play-based kindergarten teacher development programme was developed and successfully used to improve participating teachers' knowledge, skills, attitudes and practices during the first year of its implementation. Data collected through classroom observation, interviews, photographs, participating teachers' reflective journals and an evaluation questionnaire revealed that this programme had a positive impact on classroom practices and learners' active participation in learning. The essential components of the programme are described as a guide for professional teacher development for delivering indigenous play-based pedagogy (IPBP) in early childhood education.

Keywords: indigenous play; indigenous play-based pedagogy; kindergarten; professional development programme

Introduction

In recent years, kindergarten (KG) education in Ghana has continued to receive increasing attention because of the government's commitment to quality education at that level. The 2006 KG curriculum, which focuses on six learning areas (language and literacy, environmental studies, numeracy, creative activities, music, dance and drama, and physical development) recommends facilitation of children's learning through play-based pedagogy. This recommendation is viewed as an effort to reform preschool education in the kindergarten 1-2 curriculum (4-5 year olds). However, to successfully implement this play-based curriculum in the classroom, it is essential to have teachers who possess the requisite content knowledge and pedagogical skills and are confident of their ability to guide and facilitate meaningful learning through play-based pedagogy in a familiar context.

Recent research studies (Agbenyega & Klibthong, 2011; Buabeng-Andoh, 2012) and commissioned reports (Associates for Change, 2016; Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service, 2012) indicate that kindergarten teachers are ill prepared to implement the recommended play-based pedagogy successfully (Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service, 2012). Some of the reasons suggested for this unreadiness are the inadequate content coverage of play-based pedagogy at pre-service level (Associates for Change, 2016; Sofo, Thompson & Kanton, 2015; Tamanja, 2016) and the absence of continuing in-service professional development programmes to address some of the knowledge- and skills-related challenges. It is against this backdrop that an in-service professional development programme was developed for empowering kindergarten teachers in the Ghanaian setting to use familiar indigenous forms of play, including folktales and games, to teach the kindergarten curriculum. In Ghana, like most countries in the world where early childhood education has been overlooked for many decades, teachers work under difficult conditions; large class sizes and a lack of resources and teaching materials. A professional development programme that utilises indigenous games and resources is of the essences because it allows teachers to use locally available materials and resources in implementing a play-based pedagogy. In 2012, the government initiated a programme to improve the quality of kindergarten education in Ghana. To do this, the entire kindergarten education system was reviewed and subsequent recommendations made. A call for the contextualisation of play-based pedagogy by means of defining a new pedagogy that is sensitive to the culture of the Ghanaian child and appropriate training for the teachers was suggested (Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service, 2012). This recommendation, if followed through by the government and other relevant stakeholders such as curriculum developers, researchers and teachers, would help in addressing some of the difficulties that kindergarten teachers face in implementing the kindergarten curriculum.

Play in Early Childhood Education

Play has been viewed as an integral part of early childhood education and has been considered a tool for learning, a right of children and an important activity for children's well-being and holistic development. Play has traditionally been said to be characterised as child initiated, with the adults assuming passive supervisory roles (Dockett, 2011; Fleer, 2015). Recently, researchers and practitioners have challenged various theorisations of play. The idea that play is child initiated has been challenged by Fleer (2013) who argues that children's play should include adults' mediation. The notion that all play promotes learning has also been questioned, and the debate about how play relates to learning and whether the two concepts should be separated or maintained in early childhood education, is continuing (Makaudze & Gudhlanga, 2011; Pramling Samuelsson & Asplund Carlsson, 2008).

Recent studies have shown that early childhood teachers' understanding and views of the relation between play and learning impact greatly on their pedagogical decisions and practices such as classroom arrangement, the level of their involvement in children's play and the provision of support to children (Einarsdottir, 2014; Fleer, 2013). Wu and Rao (2011) conducted a study in which they examined early childhood educators' perceptions of the relationship between play and learning in German and Chinese cultures. The researchers reported that teachers' views of play and learning were mirrored in their classroom arrangement and influenced their level of participation in children's play. According to the study, Chinese teachers linked the acquisition of pre-academic and cognitive skills with children's play and frequently intervened; their German counterparts believed that children's free play allowed them to acquire social and decision-making skills and to deal with life. Both views are in agreement with Ghanaian early childhood educators' views regarding how play relates to learning. One group of educators believes that children learn both academic and social skills as they play (Abdulai, 2016); another group portrays kindergarten as a place for preparing children for formal school. The emphasis of this group is on "getting children ready for formal schooling" (Osei-Poku & Gyekye-Ampofo, 2017:78).

Early Childhood Education (ECE) Curriculum Implementation

Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, Berk and Singer (2009:19) identify two approaches to preschool curriculum delivery: the empty-vessel approach and the whole-child approach. The empty-vessel approach is characterised by direct instructional practices, teacher-centredness, worksheets, memorisation and drills. In the whole-child approach the child is regarded as an active constructor of knowledge who learns by exploring and discovering. This approach emphasises playful learning, where children find meaning in every interaction they have within a rich environment under the guidance of a supportive adult. Studies in Ghanaian kindergartens show that the role of teachers during children's play comprised mainly the provision of materials for play and supervision to ensure children did not hurt themselves (Agbagbla, 2018). These findings agree with a research study by Dockett (2011) which indicated that the role that teachers play in children's play is determined by their understanding of how children learn. According to Dockett (2011), teachers who believe that children learn by themselves do not intervene in children's play. On the other hand, teachers who believe children learn within a social context intervene in children's play to provide them with support and scaffold their learning as they play.

Lately, educators and researchers have emphasised the need for linking play and learning in a more logical manner and a more active role of teachers in children's play in early childhood settings. The term "playful learning" has been used to describe planned play activities or experiences where teachers try to mix play with learning (Bodrova & Leong, 2010; Lillard, 2013). Playful learning is a goal-oriented play experience that spans several play types linked to several educational areas. The focus of playful learning is to achieve curriculum goals through play where children learn and practice skills, attitudes and knowledge (Einarsdottir, 2014). The overriding advantage of achieving learning outcomes through play is that it permits the realisation of educational goals through contexts that are familiar and meaningful to the child, and which are, from the viewpoint of the child, innately self-motivating. Linking educational goals to play presupposes that children acquire knowledge in meaningful ways and develop favourable dispositions towards learning.

Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie (2013) note that playful learning seeks to keep an equilibrium between child-initiated play and teacher-directed play activities. Playful learning encourages adult engagement in children's play activities with the view to deliberately provide children with the needed support. The role of the teacher in playful learning, according to Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie (2013), is to provide support for children's learning during play instead of following a more instructive approach of directed teaching.

Other researchers recommend a pedagogy that integrates play and learning. Pramling Samuelsson and Asplund Carlsson (2008) for example, propose the notion of the playing learning child. The authors conceptualise play and learning as two interrelated concepts. They emphasise the common dimensions (such as creativity, joy and meaning making) of both play and learning. The authors consider play as a vital aspect of the process of learning, in which case learning involves play in the same way as play involves learning. This means that the role of the teacher during play is as important as it is during learning. According to these authors, teachers' roles include encouraging, supporting and stimulating the interests of children. The pedagogy of the playing learning child supports communication and interaction between the teacher and the children and among the children.

Play, Work and Learning: African Perspectives

In African cultures, play, work and learning are inseparable (Boyette, 2016; Michelet, 2016:234). This is because the delivery of learning content to African children involves wedging children's daily routines into the community and family livelihood (Boyette, 2016). Thus, as children engage in social life and leisure (including play) in their communities, they discover the embedded skills, knowledge and attitudes inherent in such activities (Gwanfogbe, 2011). Therefore, children in Africa do not see any difference between playing and working or participating and learning (Michelet, 2016). Ng'asike (2014), who observed the play activities of nomadic pastoral children in Kenya, noted that as the young children took care of the herds, they developed the skill to distinguish scars on the hooves of the animals, for example. According to Ng'asike, this skill and knowledge these children acquired through this process of play were relevant to their future work of rearing animals.

Furthermore, in Africa natural contexts provide children with enormous play opportunities (Ng'asike, 2014:48). Ng'asike found that nomadic children in Kenya engaged in sand and water play at riverbeds. The river ecosystem also presented children with the opportunity to "hunt birds and squirrels, collect insects, and engage in livestock herding." Ogunyemi (2016) identified five varieties of childhood play in Nigeria. She mentioned physical play, which included children running errands for adults within their neighbourhood; music and dance; children moving in groups and playing adult roles (which falls under social play); children's free play, including using readily available local materials such as empty cans, clay, sticks and plastic to create objects with which they played; games with rules, consisting of games that already have established rules which children follow; and adult-moderated play, which included moonlight storytelling, community festivals and dancing.

Various authors agree that the different forms of indigenous play promote children's learning and holistic development (Bayeck, 2018; Ogunyemi, 2016). In a Southern African study, Makaudze and Gudhlanga (2011) explored the game of riddles played in the Shona community of Zimbabwe. The game involves short oral puzzles in which objects and situations are covertly referred to in analogies to which children have to offer answers based on their understanding and observation of their environment. The study revealed that in addition to entertainment and socialisation, riddles promoted children's learning and development in almost every domain. According to these authors, riddles promote cognitive development; memorisation, quick and logical thinking as well as creative thinking. They also contend that riddles serve as a socialisation tool for children as they learn to work in teams, observe social rules such as taking turns, and develop public-speaking skills. The findings also show that children learn about their customs and cultural values and acquire knowledge about their environment through riddles.

African folktales have furthermore been found to develop academic and higher-order thinking skills in children. For example, Agbenyega, Tamakloe and Klibthong (2017) studied Ghanaian Anansi stories. The authors argue that Anansi stories can be used to teach academic concepts to children as an Anansi story easily lends itself to a discussion between the teacher and the learners, thereby affording the teacher the opportunity to evaluate learners' understanding and to make all the necessary adjustments during lesson delivery, hence promoting learners' understanding of curriculum concepts.

Moreover, African indigenous play forms have been found to promote lifelong qualities in children. Bayeck (2018) found that through Oware (a board game), children can develop skills such as patience, negotiation, spatial thinking and decision making. Wadende, Oburu and Morara (2016) also note that story-telling and a practical assignment afford young children with the opportunity to develop qualities such as being responsible for themselves and others; to do hard work and be truthful. Ogunyemi (2016) asserts that through social play children develop empathy, self-confidence and compassion.

Materials needed for play in the African context are cheap to design and readily available within the local context. Bayeck (2018) studied five board games from four African countries: Oware from Ghana; Bao from Tanzania; Moruba and Morabaraba from South Africa and Mweso (Omweso) from Uganda. Bayeck suggests that by creating holes in the ground on a playground, children could play Oware. What is being suggested here is that through the indigenous play-based programme, teachers are empowered to use diverse types of indigenous play and resources and to design play materials for children with little or no financial constraints.

Indigenous Play-Based Pedagogy

Research has shown that play-based pedagogies in early childhood education in Africa, and specifically in Ghana, are underpinned and fashioned by information on approaches that are implemented by programmes in Western contexts. This situation is problematic, as issues such as access to resources and beliefs and practices are not addressed (Pearson & Degotardi, 2016). Hence the need for a contextualised pedagogy that promotes a culturally relevant kindergarten education that takes into consideration the sociocultural context of Ghana (Abdulai, 2016).

Indigenous play-based pedagogy refers to the use of indigenous play forms as the main context of learning to promote teaching, learning and development (Abdulai, 2016; Agbenyega et al., 2017). It advocates joint adult-child indigenous play, where both teachers and learners interact in a familiar social cultural learning environment, with teachers providing learners with the emotional, social, cognitive and communicative resources to enrich their play. In an IPBP, the teacher's role includes the following: planning a lesson based on predetermined lesson objectives; selecting an appropriate game or folktale; designing appropriate hands-on, child-centred play activities; providing materials and other resources for children's play activities; joining in children's play and/or guiding children's play to extend and guide children towards intended concepts; and being open to children's ideas and contributions to knowledge.

Literature on indigenous play has mainly focused on its potential to promote learning and development in young children. However, little is said about realising the pedagogical potential of indigenous play - about how early childhood educators can exploit it to facilitate conceptual development at the kindergarten level in accordance with curricular requirements.

Research Question

While the Ghanaian kindergarten curriculum emphasises learning through play, it fails to show teachers how to employ the pedagogy to deliver curriculum content. In the study reported on here, eight kindergarten teachers participated in a participatory action research study with the aim of using different forms of familiar indigenous play in an indigenous play-based pedagogy in the kindergarten classroom. The research question that guided the study was: How can a professional development programme be used to enhance teachers' knowledge, attitudes and practices to implement an indigenous play-based pedagogy in the kindergarten classroom?

Method

The research, a participatory action study, was conducted in five kindergarten schools in the New Juaben municipality in the eastern region of Ghana. The participants were eight kindergarten teachers who had between eight to thirty-seven years of experience working with young children.

Participatory action research (PAR) researchers seek to "know with others rather than about them" (Bhana, 1999:230). PAR in schools is about actions and change of practice, and teachers participate in PAR with the view to develop and improve their own practice (Einarsdottir, 2014). Bhana (1999:235) explains empowerment as the process of "raising awareness in people of their abilities and resources to mobilise for social action." Actions that were taken were noted, and data gathered were analysed throughout the study (Bhana, 1999). The aim of the participatory action research conveyed here was to solve the problems that were important to the teachers (Einarsdottir, 2014).

The conceptual framework that underpins the development of the current professional development programme was constructed by modifying different aspects of several teacher professional development models such as the UNIVEMALASHI Project, the Collaborative Action Research Project and the Iterative Approach. The study progressed through four phases, namely diagnosis, capacity building, implementation and post-implementation.

Phase I: Diagnosis

The first phase of the study (diagnosis) lasted about three weeks. It involved one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with the eight teachers to identify their prior knowledge relating to their approaches to delivering the kindergarten curriculum and their beliefs about and attitudes towards a play-based pedagogy. The interview discussions provided an opportunity for the participants to ask questions, reflect on their practices and determine their own training needs. The overreaching findings of the diagnostic interviews showed that the teachers needed to develop in all the areas of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. The results, in addition to the information from the review of other professional development programmes and models, informed the activities of the second phase.

Phase 2: Capacity Building

This phase comprised various stages aimed at exploring ways in which Anansi stories and various Ghanaian indigenous games, identified by the teachers themselves, could be used within the framework of the play-based programme in implementing the KG curriculum. Several capacity-building workshop sessions were organised around each of the stages: The first stage (theory) focused on introducing the principles underlining the IPBP to the teachers. This was followed by a second stage (modelling), which consisted of applying the principles discussed in the first stage to model indigenous play-based teaching to the teachers, where one of the researchers acted as facilitator. During the modelling phase the teachers learned first-hand how the IPBP empowers learners to generate their own ideas and how flexible the pedagogy was. In the final stage (trialling), the teachers came up with different Anansi stories and a variety of indigenous Ghanaian games that could be used in implementing the KG curriculum. The teachers were given the opportunity to familiarise themselves with designing and using locally available materials and resources for the IPBP implementation. The participants worked together in small groups, discussing, sharing and explaining their ideas until they reached consensus. This process introduced the participants to the "culture of reflective planfulness" (Onwu & Mogari, 2004:166).

Hands-on, activity-based tasks

Hands-on, activity-based tasks were an integral part of the workshop. The activities assigned to the teachers were aimed at teaching and developing the skills of creativity (in other words, teachers should cultivate the ability to consider other alternatives) in using appropriate Ghanaian indigenous play to help learners develop their imagination and learn curriculum content. The activities were designed to encourage the teachers to be open to accommodate ideas generated by children to help the teachers use different questioning techniques for diagnosing any learning difficulties and for eliciting children's ideas. For example, four different tasks were designed around an Anansi story that was narrated to the teachers. The teachers worked in groups to complete the tasks. By completing each of the tasks, the teachers acquired knowledge, skills and attitudes relevant to the implementation of an IPBP in their actual classroom contexts.

Task one required of the group to use playdough and clay to mould different household utensils (based on the narrated Anansi story). This activity allowed the teachers to play with different textures, colours and shapes. The teachers also had the opportunity to search their immediate environment for materials or explore a play-box that was provided to them. By providing the teachers with a play-box (a box with different materials and props), the teachers got ideas on how to collect and keep materials for their use in the classroom. It was observed that by the end of the workshop sessions, more than half of the teachers had created their own play-boxes, which they later used in their classrooms during the implementation phase. In performing this activity, the teachers made decisions regarding alternative sources to identify and design appropriate materials for their lessons.

In the second task, the teachers were asked to think about the domains of development that could be promoted through the activities they engaged in. This task was important because in the actual classroom teachers would have to design activities that would promote children's development in all the different domains (physical, social, emotional, language and psycho-social) to reflect the general goals of the Ghanaian KG curriculum (Curriculum Research and Development Division [CRDD], 2004). The group's answers included fine-motor, hand-eye-coordination, social and thinking skills. According to the teachers, fine motor skills and hand-eye-coordination are promoted through moulding with playdough and clay. They believed that these skills were particularly important for formal schoolwork, which require of children to do a lot of writing.

The third task required of the teachers to identify concepts in the KG curriculum that were evident in the activities that they performed. The teachers named shapes, colours and textures, and compared sizes and weight. The purpose of this activity was to allow the teachers to make the link between a selected Anansi story, activities, and the KG curriculum concepts. The teachers learned in reverse order - storyline, tasks (activities) and concepts. In the actual classroom situation, the teachers would already have a topic (concept), such as shape, colour or texture. The teacher would then have to select a storyline that could help teach the concepts and then design activities through which the concepts could be learned.

According to the Ghanaian KG curriculum, learning should be presented to young children holistically and not in fragments. The curriculum therefore requires of teachers to employ an integrated approach to teaching in the KG. The fourth task was thus designed for teachers to think about possible ways of integrating learning areas in the KG through the implementation of the IPBP. The teachers realised that various aspects of numeracy (shapes), literacy (listening to the story), environmental studies (family), physical education (fine motor development), creative arts (moulding) and music and dance (singing) were included in the Anansi story.

Phase 3: Classroom Implementation

In this phase the eight teachers employed Anansi stories and other indigenous games such as Nana wo ho and Pilolo to teach the KG curriculum concepts. In three of the five schools that participated in this study, the teachers worked in pairs (although each of the teachers had her own kindergarten class). The remaining two schools had only one teacher each, who worked individually. The paired teachers worked collaboratively, planned their lessons together and supported each other in facilitating lessons based on indigenous play. The teachers took turns to teach and to observe and provide constructive feedback aimed at improving subsequent lessons. The researchers also provided feedback to the teachers to improve subsequent lessons.

The Final Phase: Post-Implementation

This phase was aimed at evaluating the outcome and impact of the indigenous play-based programme on the teachers and the learners. One-on-one individual semi-structured interviews were employed with the eight teachers to discuss how they experienced the implementation of the indigenous play-based pedagogy. This phase offered the teachers the opportunity to explain their reasons for the changes in their practices and to point out possible challenges they encountered during the implementation.

The following data collection methods were used to gather data during the study.

1) Interviews: Each of the eight kindergarten teachers participated in two interviews: the first at the beginning of the study and the second towards the end of the study. The first interview was aimed at identifying teachers' training needs. The second was conducted to further discuss how the teachers implemented the IPBP and how their participation in the indigenous play-based professional development programme (IPBPDP) influenced the way they implemented the KG curriculum.

2) Observations: Each participating teacher was observed at least twice. The first observation focused primarily on how the teachers applied the principles of an indigenous play-based pedagogy. Further observations were aimed at assessing the progressive improvement and refinement of the implementation of the IPBP. Observer schedules were used at this point.

3) Photographs: The teachers themselves took photographs that reflected what they were doing and the changes that had occurred during the study. The teachers also used the photographs to document the impact of the implementation of the IPBP on their learners. The photographs were further used to elicit discussion during the second interviews, giving the teachers the opportunity to reflect on their practices.

4) Reflective journals: The participants, who were also considered co-researchers, were encouraged to document their reflections on what they did, how they did this and to indicate how they felt about the implementation of the IPBP. To assist the teachers in completing the reflective journals, they were provided with guidelines on different aspects of the teaching and learning process to reflect on.

5) Evaluation questionnaires: A year after the implementation of the IPBP in the participating schools, the head teachers and participating teachers answered questionnaires to indicate the impact of the study on the practices of the teachers and possibly on their learners.

Data were analysed throughout the data collection period and at the end. For the purpose of data triangulation, data were collected from different sources. Member checking was used as a quality measure. During the initial stages, member checking was done informally, and in the final stages, participants commented on the findings and conclusions.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria. All participants were made to understand that their participation was voluntary and anonymous, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information. Participants signed consent for their photographs to be used in the dissemination of the study.

Results

The Situation Before the Study

The study included five public kindergartens in the eastern regions of Ghana. Like all public kindergartens in Ghana, the participating kindergartens open at 7:30 in the morning and close at 14:00 in the afternoon. The children spend about 7 hours of every day of the week at the kindergartens. A typical day in the kindergarten commences with a morning assembly at 8.00, after which children "march" into their classrooms. The teachers follow timetables that indicate specific learning areas (subjects) to be studied at a particular time, a practice similar to that in formal schools. Children study three or four subjects a day: language and literacy (lesson A: pre-reading and lesson B: reading aloud); numeracy and environmental studies. Each subject is allocated a 30-minute slot during which teachers teach and assess children's learning. The routines also include snacks, outdoor games, lunch and rest breaks. Children often engage in different forms of games during outdoor playtime, which is usually unsupervised.

Prior to the study, the curriculum implementation was mainly teacher-centred; learners passively memorised what they were taught. The teachers employed direct instruction and then used familiar objects, such as drinking straws and bottle tops, to teach the curriculum concepts. It was clear from the teachers' initial interviews that they were aware that the KG curriculum expected of them to employ a play-based pedagogy at the kindergarten level; however, they admitted that they could not employ the required pedagogy because they lacked the necessary knowledge and skills. Nevertheless, they were willing to be trained in using indigenous play that provided a familiar socio-cultural context for teaching and learning in the kindergarten context.

Evolution of Indigenous Play-Based Pedagogical Practices

During the capacity building workshop, the kindergarten teachers took turns to narrate Anansi stories and perform different indigenous games. The teachers were involved in discussions on the ways in which the different stories and games could be used to teach different concepts from the curriculum to promote active child participation and enjoyment. Analysis of the interview data, the researcher's observation field notes and the participants' reflective journal entries and photographs showed that the teachers made conscious efforts to change the way they implemented the kindergarten curriculum following their participation in the professional development programme. These changes were exemplified in four aspects, namely the teachers' knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and consequently their approaches to implementing the indigenous play-based pedagogy.

Teachers' Knowledge

The teachers demonstrated their acquisition of knowledge in the implementation of the indigenous play-based pedagogy. The change in teaching practice resulting from their acquisition of knowledge and skills was shown in the way that they taught different curriculum concepts; creating their own stories and how they arranged their classrooms to create a relaxed and welcoming learning environment. This is how the teachers explained how they taught different concepts:

I did not know I could use 'Nana wo ho' to teach two- or three-letter words; … after the workshop, we now know… .

It wasn't like first, where I just tell the story then we get up and go. … this time we extract a lot and learn a lot from the story.

I used an Anansi story to teach parts of the body … I accompanied the story with the box, it is like a television, so when I was telling the story then I was showing them the pictures. After that I asked them some questions and then I asked them to mould the characters in the story.

Creation of own stories

The teachers understood from the participatory action research that they needed to be creative, that they could create their own stories that would help them teach specific curriculum concepts: "… sometimes I am even tempted to create my own story … because I know that through that the children learn a lot."

Classroom seating arrangement

The teachers acquired the knowledge and skills that helped them arrange their classrooms in varied ways. The teachers did not regard the lack of space as a challenge to the implementation of an indigenous play-based pedagogy: This comment is a representative view: "… previously we were thinking we did not have enough space, but after the workshop we know that we can even set up certain arrangements in the classrooms for the children to feel comfortable."

Use of outdoor spaces

The teachers engaged children in outdoor activities in order to provide different learning environments that engaged the emotions of the learners:

When I am teaching …, I try to change the environment. When I am using a story and the play to teach, I take the learners outdoors. This helps to change their mood and they feel free to express themselves.

Figures 1 and 2 confirm the teachers' acquisition of knowledge, shown in the way that they arranged their classrooms during lessons, and how they used outdoor spaces.

Figure 1 illustrates a semi-circular seating arrangement during an Anansi story session. The same semi-circle is seen in Figure 2, where the teacher used it outdoors.

Teachers' role in children's play

The results show that after their participation in the study, the teachers performed active roles in children's play, which helped the children to learn concepts. The teachers joined the children in their play activities to demonstrate concepts to them and provide materials for their play. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the teachers' active roles during the children's play to promote learning.

In Figure 3 the teacher provided culturally relevant materials for children's play and discussed their uses with the learners. In Figure 4 the teacher demonstrates how to use clay to mould different characters in the story narrated earlier.

Teachers' attitudes

Evidence from the second interview and classroom observation indicates that the teachers' attitudes towards the KG curriculum delivery had changed. The teachers collaborated with each other in designing and mobilising resources and teaching-learning materials. The teachers even teamed up with other teachers and older learners to mobilise resources.

We have even decided to ask the primary school teacher … to ask the primary school pupils to bring us clay. We will keep it somewhere and anytime we need it we go for it.

Change in teacher-child interactions

The teachers similarly indicated the change in their mode of interacting with their learners during lessons. They no longer assumed the position where they were the knowledge pot and the learners passive recipients of the teachers' knowledge; they were open to learners' contributions to knowledge construction in the classroom and viewed themselves as co-learners. The following teacher's voice and Figure 5 confirm this: "… They, the learners, will rather teach you, you will not teach them, because it helps them to think wide and far."

In Figure 5 the children suggested that the teacher create human facial features such as nose, eyes and mouth. The teacher had not planned to draw those features, she only agreed to do so when the children insisted that a human being must have such features.

Hands-on, active child-centred methods

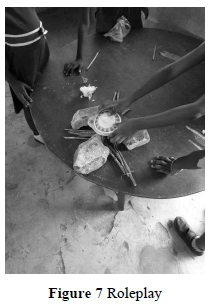

The data from the interviews, observations and photographs reveal that the teachers had changed the instructional methods that they used to implement the KG curriculum. The majority (seven) of the teachers employed the narration of Anansi stories in a combination with hands-on and child-centred approaches such as roleplay, dramatisation and moulding. Figures 6 and 7 show examples of the different methods that the teachers employed to implement the curriculum concepts.

In Figure 6 the children are dramatising a forest scene from the story the teacher had narrated to them earlier in the classroom. Figure 7 shows children roleplaying making supper.

Summary and Discussion

Before starting the participatory action research study, the kindergarten curriculum implementation was not play-based, although it was the recommended pedagogy. Teachers mainly employed lecture methods with emphasis on the teaching of academic concepts with the aim of preparing the children for primary school. This agrees with other studies that show that although kindergarten teachers believed that children learnt better through play-based pedagogies, they did not implement these (Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service, 2012).

During the participatory action research study, the kindergarten teachers engaged in discussions and listened to lectures about how to facilitate curriculum concepts through indigenous folktales and games, using locally available materials and resources to enrich the implementation of the kindergarten curriculum. Increasingly they found ways to link indigenous play to their classroom pedagogical practices. They systematically planned for play, designed materials (most of which they collected from the school or home environment without having to buy) to support children's play and they participated in the children's play. They employed child-centred play activities such as storytelling, dramatisation, roleplay, moulding with clay and drawing to deliver the curriculum concepts. When the teachers used folktales and games in their lessons, children's interest and participation in the lessons increased. This agrees with other findings (Einarsdottir, 2014).

The teachers asserted that when indigenous folktales and games were used to teach curriculum concepts, children learned more concepts, and the development of other aspects such as language, emotional, social, physical (fine and gross motor) skills were promoted. This supports other findings which show that indigenous play-based pedagogy, in addition to facilitating academic conceptual development, promotes children's holistic development (Agbenyega et al., 2017; Awopegba, Oduolowu & Nsamenang, 2013; Pearson & Degotardi, 2016; Sofo & Ocansey, 2014).

Although the kindergarten teachers made several changes in planning for play, designing play materials, participating in children's play and being open to children's construction of knowledge, the teachers did not fully exploit the extended learning potential of the new approach. Classroom observation showed that on most occasions the teachers did not interrogate children's thinking behind their creations and ignored children's suggestions to explore certain topics further. The teachers mainly focused on achieving their lesson objectives and did not want to extend the lessons. Although the teachers knew that children learned more concepts through indigenous play-based pedagogy, they missed opportunities to expand children's lessons beyond what they had planned to teach. This may reflect the teachers' lack of confidence to allow the children to direct the learning process in the kindergarten classroom, making them ignore issues that children raised during lessons.

Participatory action research aims at increasing teachers' awareness of their capacity to improve their classroom practices (Einarsdottir, 2014; Onwu & Mogari, 2004). The eight kindergarten teachers' reflections showed that the project opened their eyes to what they could do, empowered them and strengthened their beliefs. The teachers saw that an indigenous play-based pedagogy promoted children's holistic development, and their participation in the study appeared to have strengthened that belief. By participating in the study, the teachers reflected on their practices. Despite their active participation in the study and the fascinating changes they had made to their kindergarten classrooms during the study, it seemed that the traditional lecturing and teacher-centred approach to implementing the kindergarten curriculum could not be completely replaced with the IPBP. The IPBP is considered time-consuming with regard to planning, organising and designing of materials, and the children need sufficient time to explore the materials during the lesson. In contrast, the traditional lecture method focuses on quickly teaching a set of concepts within the stipulated time.

This participatory action research was used to deliver a professional development programme for the teachers to work collaboratively with the researchers. The study addressed crucial issues in kindergarten education in Ghana. The aim was to improve teachers' attitudes, beliefs and pedagogical practices and to benefit the participating schools and ultimately the education of kindergarten children in Ghana. Changing approaches to education is no doubt a long-term process, and hopefully this study was a step in the right direction.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank all the teachers and learners who took part in this study for allowing us to share their space during this study.

Authors' Contributions

FED wrote the manuscript and provided data for the analysis. JVH was the supervisor for the PhD study on which this article is based. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 31 October 2018; Revised: 6 October 2019; Accepted: 15 November 2019; Published: 31 August 2020.

References

Abdulai A 2016. Pedagogy of indigenous play: The case of Ghana's early childhood education. International Journal of Research and Reviews in Education, 3:28-34. Available at http://www.bluepenjournals.org/ijrre/pdf/2016/December/Abdulai.pdf. Accessed 1 August 2020. [ Links ]

Agbagbla F 2018. A professional development programme for Ghanaian kindergarten teachers to implement an indigenous play-based pedagogy. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. Available at https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/69988/Agbagbla_Professional_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 July 2020. [ Links ]

Agbenyega JS & Klibthong S 2011. Early childhood inclusion: A postcolonial analysis of pre-service teachers' professional development and pedagogy in Ghana. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 12(4):403-414. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2011.12.4.403 [ Links ]

Agbenyega JS, Tamakloe DE & Klibthong S 2017. Folklore epistemology: How does traditional folklore contribute to children's thinking and concept development? International Journal of Early Years Education, 25(2):112-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1287062 [ Links ]

Associates for Change 2016. The impact assessment of the Untrained Teacher Diploma in Basic Education (UTDBE) in Ghana. Accra, Ghana. Available at https://docsend.com/view/dzwwrxy. Accessed 5 May 2018. [ Links ]

Awopegba PO, Oduolowu EA & Nsamenang AB 2013. Indigenous early childhood care and education (IECCE) curriculum framework for Africa: A focus on context and contents. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: UNESCO: International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa. Available at http://www.iicba.unesco.org/sites/default/files/Fundamentals%20of%20Teacher%20Education%20Development%20No6.pdf. Accessed 17 August 2020. [ Links ]

Bayeck RY 2018. Why African board games should be introduced into the classroom. The Conversation, 7 January. Available at http://theconversation.com/why-african-board-games-should-be-introduced-into-the-classroom-88139. Accessed 3 June 2018. [ Links ]

Bhana A 1999. Participatory action research: A practical guide for realistic radicals. In M Terre Blanche & K Durrheim (eds). Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Bodrova E & Leong DJ 2010. Curriculum and play in early child development. In RE Tremblay, M Boivin & RDeV Peters (eds). Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Available at http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/textes-experts/en/774/curriculum-and-play-in-early-child-development.pdf. Accessed 4 August 2018. [ Links ]

Boyette AH 2016. Children's play and culture learning in an egalitarian foraging society. Child Development, 87(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12496 [ Links ]

Buabeng-Andoh C 2012. An exploration of teachers' skills, perceptions and practices of ICT in teaching and learning in the Ghanaian second-cycle schools. Contemporary Educational Technology, 3(1):36-49. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ca7d/a8aa6839dd2175fcdedf15d04b13504661d9.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2020. [ Links ]

Curriculum Research and Development Division (CRDD) 2006. Curriculum for kindergarten 1 - 2. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Education Youth and Sports. [ Links ]

Dockett S 2011. The challenge of play for early childhood educators. In S Rogers (ed). Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: Concepts, context and cultures. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Edwards S & Cutter-Mackenzie S 2013. Pedagogical play types: What do they suggest for learning about sustainability in early childhood education? International Journal of Early Childhood, 45:327-346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-013-0082-5 [ Links ]

Einarsdottir J 2014. Play and literacy: A collaborative action research project in preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(1):93-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.705321 [ Links ]

Fleer M 2013. Play in the early years. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fleer M 2015. Pedagogical positioning in play - teachers being inside and outside of children's imaginary play. Early Child Development and Care, 185(11-12):1801-1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1028393 [ Links ]

Gwanfogbe MB 2011. Africa's triple education heritage: A historical comparison. In AB Nsamenang & TMS Tchombe (eds). Handbook of African educational theories and practices: A generative teacher education curriculum. Bamenda, Cameroon: Human Development Resource Centre. Available at http://www.thehdrc.org/Handbook%20of%20African%20Educational%20Theories%20and%20Practices.pdf. Accessed 2 August 2020. [ Links ]

Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Berk LE & Singer DG 2009. A mandate for playful learning in preschool: Presenting the evidence. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lillard AS 2013. Playful learning and Montessori education. The NAMTA Journal, 38(2):137-174. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1077161.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2020. [ Links ]

Makaudze G & Gudhlanga ES 2011. Playing and learning: The interface between school and leisure in Shona riddles. Mousaion, 29(3):298-314. [ Links ]

Michelet A 2016. What makes children work? The participative trajectory in domestic and pastoral chores of children in southern Mongolia. Ethos, 44(3):223-247. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12130 [ Links ]

Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service 2012. Programme to scale-up quality kindergarten education in Ghana. Available at https://issuu.com/sabretom/docs/10_12_12_final_version_of_narrative_op. Accessed 20 July 2016. [ Links ]

Ng'asike JT 2014. African early childhood development curriculum and pedagogy for Turkana nomadic pastoralist communities of Kenya. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2014(146):43-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20072 [ Links ]

Ogunyemi FT 2016. The theory and practice of play. Paper presented at the Play Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 12-14 July. [ Links ]

Onwu GOM & Mogari D 2004. Professional development for outcomes‐based education curriculum implementation: The case of UNIVEMALASHI, South Africa. Journal of Education for Teaching, 30(2):161-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747042000229771 [ Links ]

Osei-Poku P & Gyekye-Ampofo M 2017. Curriculum delivery in early childhood education: Evidence from selected public kindergartens in Ashanti region, Ghana. British Journal of Education, 5(5):72-82. Available at https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/53691476/Curriculum-Delivery-in-Early-Childhood-Education.pdf?1498666801=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DCURRICULUM_DELIVERY_IN_EARLY_CHILDHOOD_E.pdf&Expires=1598955740&Signature=BersJIyq0uVuCjJaEF1uPLj4Kl9oCAd1wuxZjgF~dl346PhsNDTKiLQzxsVF14vxk4wEhFpgH4Q55F~~gNz4P5omYcE6jVkEBvbTTLNc8Md3~aQOT3j4Mp0IgsrrIhSeY5PZiG1w2zMZwEsT8Tu62wgGOTEwPs~xdEf22hl17uReHOU~nrrIQm9Vz9nQvWGEFMQk1RGIvHsHrUQbxsYOrcU5Gqo~BmQV0-vySIqImS09WNuQxOwBznVYEwymP1JnLjaBLBHb9M-K4FJc-qcgcSjayNfCwlAcHIIQKpAX7MvVDMsqeFPA8rld8Ymf1-F82WObNraDdE5bkCiOx6-zag__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. Accessed 14 July 2020. [ Links ]

Pearson E & Degotardi S 2016. Innovative pedagogical approaches in early childhood care and education (ECCE) in the Asia-Pacific region: A resource pack. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Available at https://worldomep.org/file/ARNEC-Resorce-pack.pdf. Accessed 2 August 2020. [ Links ]

Pramling Samuelsson I & Asplund Carlsson M 2008. The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(6):623-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802497265 [ Links ]

Sofo S & Ocansey R 2014. Inter-disciplinary learning. Ghana Physical Education and Sports Journal, 3:6-9. [ Links ]

Sofo S, Thompson E & Kanton TL 2015. Untrained teachers diploma in basic education programme in Ghana: Teacher trainees' and lecturers' perspectives. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 5(6):7-13. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Seidu_Sofo/publication/297760334_Untrained_Teachers_Diploma_in_Basic_Education_Program_in_Ghana_Teacher_Trainees'_and_Lecturers'_Perspectives/links/577d253b08aed39f598f6a15/Untrained-Teachers-Diploma-in-Basic-Education-Program-in-Ghana-Teacher-Trainees-and-Lecturers-Perspectives.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020. [ Links ]

Tamanja EMJ 2016. Teacher professional development through sandwich programmes and absenteeism in basic schools in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(18):92-108. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105900.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020. [ Links ]

Wadende P, Oburu PO & Morara A 2016. African indigenous care-giving practices: Stimulating early childhood development and education in Kenya. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 6(2):a446. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i2.446 [ Links ]

Wu SC & Rao N 2011. Chinese and German teachers' conceptions of play and learning and children's play behaviour. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19(4):469-481. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2011.623511 [ Links ]