Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 no.3 Pretoria ago. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1857

ARTICLES

The relationship between assessment and preparing BEd undergraduate students for the South African school context

Nicole Imbrailo; Karen Steenekamp

Department of Education and Curriculum Studies, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. karens@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The Bachelor of Education (BEd) undergraduate degree at a university in the Gauteng province, South Africa, aims to prepare pre-service teachers by using their experiences to expose them to the South African schooling context. This is done using a scaffolded process that includes formative assessment, summative assessment and Work-Integrated Learning (WIL, also known as teaching experience). This paper describes research findings based on a sequential mixed method design used within a constructivist paradigm to collect data on the role of assessment in pre-service teacher preparation. Eighty participants answered 16 questions on a nominal scale, and from this sample, 8 participants took part in semi-structured, one-on-one interviews. Based on the findings, it was concluded that all types of assessment were beneficial for pre-service teacher preparation as part of an assessment schedule - especially the case with WIL. However, WIL was criticised for not aligning with the current context and for a need to include the realities of paperwork, policies and systems as well as the emotional strain experienced by in-service teachers. The results suggest that by making WIL more authentic could impact pre-service teachers during their careers when deciding whether to remain in the profession.

Keywords: assessment; formative; preparation; pre-service teacher; summative; work-integrated learning

Introduction

In this article we report on a research study aimed at determining the relationship between assessment and the preparation of pre-service teachers for teaching practice. The first objective of the study was to determine whether assessment adequately prepared pre-service teachers for in-service experiences. The second objective was to determine how and whether WIL assessment provided pre-service teachers with an interface between what the university assessed and what pre-service teachers experienced in schools.

This study is relevant to South African and international institutions offering a Bachelor of Education degree as it provides insight on the types of assessments that institutions can use to best prepare pre-service teachers during their studies. Institutions can also focus on the types of WIL experiences that pre-service teachers are being exposed to.

The BEd undergraduate degree presented at a Gauteng university where the study was conducted uses a scaffolded assessment process to prepare pre-service teachers for future teaching in the South African context (Aragon, Culpepper, McKee & Perkins, 2014; Faez, 2012). The diverse contextual environment in South Africa can be challenging for teachers who are not prepared to accommodate learners from different genders, races, religions, cultures, languages and/or disabilities (Faez, 2012; Landsberg, Krüger & Swart 2016; Matsko & Hammerness, 2014). It is essential to monitor the development of pre-service teachers through assessment to identify whether they are aware of how the schooling system works and whether they are prepared to operate within that environment (Engelbrecht, Nel, Nel & Tlale, 2015; Walton, Nel, Muller & Lebeloane, 2014). Mentorship plays a role in assisting pre-service teachers to feel better prepared for these environments while also learning how to manage classroom discipline within an inclusive environment (Christoforidou, Kyriakides, Antoniou & Creemers, 2014). According to Brown, Lee and Collins (2015), well-prepared pre-service teachers whom they surveyed in the United States of America felt confident about handling day-to-day situations in the classroom, leading to job satisfaction. This appears to contrast with the experiences of novice and in-service teachers in South Africa who have raised concerns about job satisfaction, and report feeling overwhelmed due to a lack of preparedness (Walton et al., 2014).

Literature Review

Within the BEd programme, assessment is a scaffolded process that gradually prepares pre-service teachers for formal assessment. During the first two years of their teaching experience, pre-service teachers are not formally assessed on teaching practice during the observation period or teaching experience, as the purpose of the observation period is to allow pre-service teachers to become familiar with the expectations and contextual challenges of teaching (Landsberg et al., 2016). During this period pre-service teachers gradually start teaching classes and are assessed on their reflection of these experiences by completing formative assessments in the form of assignments. During the last two years of WIL, pre-service teachers are assessed formally on their teaching practice on how they incorporate the theoretical component of their BEd degree practically into the classroom (Tuytens & Devos, 2011; Waggoner & Carroll, 2014; Wiliam, 2011). Over the span of their teaching experience, feedback is provided by the mentor teachers and lecturers to guide the pre-service teachers' teaching practice and to establish an understanding of best practice (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2015b). Assessment of the pre-service teacher becomes gradually more stringent as more comes to be expected of them.

Assessment of pre-service teachers

As noted above, assessment is a scaffolded process, important for pre-service teacher preparation. Assessment is a tool that monitors the development of pre-service teachers, indicating their achieved level of mastery. It is a continuous process and should have clear intended outcomes. These processes and outcomes include pre-service-teachers' study patterns, their understanding of the learning content and lecturers' grading and feedback of assessments (Brookhart, 2004). This underlines the importance of assessment as a structured and scaffolded process for preparing pre-service teachers. Assessment of pre-service teacher preparation needs to be valid and reliable. Valid assessment must measure the level of mastery in relation to the outcomes stipulated by the course content. Assessment also needs to be reliable, with pre-service teachers evaluated in a manner that is free from bias. Assessment that is valid and reliable gives a reliable and authentic indication of pre-service teacher preparation (Reddy, Le Grange, Beets & Lundie, 2015).

In this study we used Kirkpatrick's four levels of evaluation (Tuytens & Devos, 2011), namely: reactions, learning, transfer and results. Level one focuses on how the pre-service teacher reacts to the content. Positive reactions do not guarantee learning, while negative reactions may decrease the possibility of learning. Level two focuses on how much has been learnt and whether there has been an advance in skills, knowledge or attitude through what has been conveyed. Level three focuses on how this information has changed the pre-service teacher's behaviour. This is where pre-service teachers begin to modify their practice according to the information they have gained. Level four determines how the pre-service teacher has changed his or her practice as a direct result of what has been learnt and understood about the expectations of the role (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2016). Pre-service teachers who complete the BEd undergraduate degree are assessed using both formative and summative assessment in addition to practical assessment through WIL (Tuytens & Devos, 2011; Waggoner & Carroll, 2014; Wiliam, 2011).

Formative assessment

Formative assessment is a continuous process that provides evidence about pre-service teachers' ability to integrate course content into informed teaching practice (Sztajn, Confrey, Wilson & Edgington, 2012). Examples of formative assessment include class activities, group work and assignments that are integrated into classroom practice (Wiliam, 2011). Wiliam (2011) suggests that formative assessment should be used as a guideline to make instructional decisions that Verberg, Tigelaar and Verloop (2015) believe support learning and aid development. Learning support and development can be achieved through timely and specific feedback of performance which is connected to the pre-established criteria of the course content (Sztajn et al., 2012).

Feedback has been found to motivate pre-service teachers (Wiliam, 2011) to reflect on developmental areas (Gulikers, Biemans, Wesselink & Van der Wel, 2013), enabling the learning process to be scaffolded by the lecturer or mentor teacher through re-teaching, revisiting and emphasising content not yet mastered (Cornish & Jenkins, 2012). Formative assessment informs summative assessment (Gulikers et al., 2013) as it not only recognises strengths but identifies developmental areas in pre-service teachers' practice before they complete a summative assessment designed to provide evidence of teacher performance and to identify whether the teacher has been prepared adequately to receive certification (Cornish & Jenkins, 2012).

Summative assessment

Summative assessment identifies the level of mastery of the pre-service teacher in relation to the outcomes stipulated by the course content (Gulikers et al., 2013) and can also indicate the pre-service teacher's level of competency (Bakx, Baartman & Van Schilt-Mol, 2014). The results obtained from summative assessments are used to judge the pre-service teacher's performance after a process of scaffolded learning support and development and are the outcomes of assessment, as previously mentioned in the review of literature. These results are quantifiable and should align with the pre-service teacher's successful induction into the field of teaching (Cornish & Jenkins, 2012). Summative assessments are conducted at the end of the learning cycle as the final level of task complexity that acts as a reflection of the pre-service teacher's preparation (Nel, Nel & Hugo, 2012) and should be used in conjunction with the results obtained from WIL teaching practice.

The constructivist position argues that the learner needs an opportunity to interact with sensory data, as experienced through the WIL component of assessment, which prepares pre-service teachers for the future school context. This requires the pre-service teacher's active participation and engagement as he or she reflects on social experiences and interactions through the process of assimilating and accommodating of new knowledge to reach equilibrium (Nel et al, 2012). During assimilation, the pre-service teacher is taught skills, abilities, values and attitudes that are required for in-service teaching (Piaget, 2013). The pre-service teacher takes this information and tries to make meaning of these and their own attributes until they reach acceptance of these attributes through accommodation. Equilibrium is reached when the assimilated actions and accommodations of pre-service teachers have led to a desired result (Piaget, 2013): a confident and prepared pre-service teacher. During the learning process, universities are making an effort to prepare pre-service teachers by equipping them with attributes believed to be important for future teachers, in which knowledge is constructed through experiences and supportive learning. Woolfolk Hoy (2014) reiterates the importance of learning that is embedded in authentic experiences through the process of self-awareness, shared responsibility and the exploration of multiple perspectives. WIL is discussed in the next section, using experiential learning theory.

Work-integrated learning

The BEd undergraduate degree offers a range of summative and formative assessments including those related to WIL. This learning is based on the experiential learning theory as described by Kolb (2015). Kolb describes experiential learning as a transformative learning process that requires pre-service teachers undergo an ongoing four-stage cycle of learning through experience.

The learning process begins with concrete experiences which provide pre-service teachers with information. In the South African schooling context, they gain these experiences through WIL (also known as teaching experience). Pre-service teachers then use these experiences to progress to stage two in which they process the experiences by reflecting on them to construct new understandings about them. During reflection, the pre-service teachers deconstruct these experiences with their newly gained information to inform and improve their practice. Reflection takes the newly gained information and makes it meaningful to the pre-service teachers, drawing on the human experience of perception and interpretation to construct new meanings (Goby & Lewis, 2000; Sherwood & Horton-Deutsch, 2012).

Once reflection has occurred, pre-service teachers then progress to stage three, which is abstract conceptualisation. Pre-service teachers take this new, meaningful information and apply it to multiple aspects of their teaching. For example, the pre-service teacher may note that one class of learners responds to positive reinforcement using stickers or praise written in their books, while another class may respond to being allowed to leave earlier for break. The teacher could then use this specific information about each class to apply to multiple aspects of their teaching such as classroom discipline strategies, management and motivation. The last of the four stages is active experimentation, in which pre-service teachers test their ideas in real-life situations (Schenck & Cruickshank, 2015; Weinstein, 2013). The cycle then begins again as the pre-service teacher actively experiments in the classroom and forms new concrete experiences. The process is transformative in that it allows pre-service teachers to take in new information, make it meaningful and construct their own practice (Goby & Lewis, 2000). Knowledge is constructed through concrete experiences in the classroom and abstract experiences that take place thereafter. Both concrete and abstract experiences are beneficial in preparing pre-service teachers (Kolb, 2015).

The theory behind WIL is that it encourages students to reflect on their practice and refine it through experience. WIL is the practical component of the BEd degree that exposes pre-service teachers to the schooling context from their first year in a scaffolded manner.

Pre-service teachers specialising in the Senior-Further Education and Training (FET) phase BEd undergraduate qualification need to complete teaching experience in Grades 7 to 12. In their first year of WIL, they are exposed to the school's context during the observation week (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2015a). Following this, pre-service teachers have the opportunity to observe the classroom through the lens of their mentor teacher by focusing on teaching approaches, classroom management strategies and organisational and administrative tasks associated with the profession (Lee, Tice, Collins, Brown, Smith & Fox, 2012). During this time, the pre-service teacher can ask questions and raise concerns with the mentor teacher to develop content-specific information (Matsko & Hammerness, 2014). The pre-service teachers are required to teach for three weeks in their second and third years and to demonstrate what they have learnt during this time through formative assessments, which are marked by their lecturers. In their final year, pre-service teachers are required to complete twelve weeks of teaching experience at a school. During this time, the pre-service teacher will be expected to prepare and present at least one lesson that is externally evaluated by their lecturer (Council of Higher Education, 2011). The lecturer will use a rubric to evaluate the pre-service teacher on their level of competence in the classroom ranging from classroom presence, classroom management, introduction of the lesson, transition into the teaching-and-learning phase and how the student concludes the lesson (Bakx et al., 2014). All aspects that are evaluated during this evaluation stem from the expectations of the student at the stipulated National Qualifications Framework (NQF) level and in terms of the Department of Higher Education and Training (2015b).

Methodology

A constructivist lens was the most appropriate for this study as this paradigm provides an explanation of how pre-service teachers construct their own reality about preparation during their undergraduate BEd studies through events and activities. Constructivism assumes that knowledge is constructed socially as people interact with the world around them (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014), and that multiple realities exist because reality is constructed through personal experiences, interpretation and application of knowledge (Du Plooy-Cilliers, Davis & Bezuidenhout, 2014). This research paradigm was the most suited to the aim of this study as we focused on multiple realities constructed by participants during their BEd undergraduate degree and their experiences gained during their first few years as novice teachers (Charmaz, 2014). We were then able to investigate the meaning underlying these events and activities to find a shared truth.

In this study we needed to take these multiple realities into consideration as all pre-service teachers have different learning experiences of assessment, depending on their assimilation and accommodation of information. Reasons for this include whether they had read the expectations before starting the assessment; time taken to complete the assessments; whether they had consulted with others; whether they had read through feedback and remembered to apply it to their next task; how much time they had set aside to study for tests and examinations; and whether they knew how to study effectively according to their learning styles. To identify meaningful patterns or trends in the assessment of pre-service teacher preparation for the South African schooling context, the study explored these realities through a mixed method design.

In this study we used an explanatory, sequential mixed method designed to answer the research question. We examined, firstly, whether pre-service teachers were prepared for the South African context (quantitative research) and, secondly, how they were prepared through assessment for the South African context (qualitative research). The purpose of the explanatory, sequential design was to understand the multiple realities formed by each participant within their specific teaching contexts and the factors that determined whether, and how, they were prepared for this context (Tran, 2016).

Population

Participants were purposively sourced through social media. Eighty novice teachers who had completed a BEd undergraduate degree (Senior-FET phase) from a university and who had one to five years' experience voluntarily participated in the quantitative data collection. In order for us to develop an understanding of how this four-year qualification prepared pre-service teachers, all participants were required to have a BEd undergraduate degree. No participants with a post-graduate certificate in education were selected as they did not hold a four-year qualification. The participants completed a questionnaire containing 16 questions focusing on assessment preparation.

Eight participants volunteered to complete the interview based on their preparation for the teaching profession and were divided into three participant types, namely: confirming cases, disconfirming cases and neither confirming nor disconfirming cases. Participants who were prepared answered "yes" to more than 93% of the questions (confirming cases), participants who were unprepared answered "no" to 40% or more of the questions (disconfirming cases) and participants who were moderately prepared answered "yes" to 50% of the questions. Participants who scored 7.5 were exactly mid-way between a confirming or disconfirming case and could not be considered as either, forming a third participant type. All three participant types were selected for semi-structured, one-on-one interviews so that we could gain insight into why some participants felt adequately prepared through assessment, some felt inadequately prepared and some felt prepared in some areas but not in others. Using the three participant types helped to contextualise the data by indicating whether the frequency of responses was linked to the South African schooling context.

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

Quantitative data were collected using a self-administered, closed-ended questionnaire with 16 "yes"/"no" questions that included a comment section to allow for elaboration on the nominal scale responses.

Once data had been collected from all 80 participants, analysis was done using deductive reasoning, also known as "top-down" logic (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). The process of deductive reasoning takes one or more statements (or premises) made by participants and uses these to reach a logical conclusion. An argument is "deductively valid if its conclusion follows with certainty from the premises," meaning that the conclusion drawn from the premise is true (Dowden, 2017:335). The data were transcribed into an Excel document using the coded segments in the questionnaire. For the comment section, the coding system needed to differ from the first two tabs. The comments were read and annotated using open coding; this allows the researcher to ask questions about the data and make comparisons between data to find differences and similarities.

Transcripts were annotated with labels that included relevant words, phrases or sentences. Open coding enabled us to interpret the meaning of the multiple realities experienced by each participant and interpret this to construct meaning in a constructive research paradigm (Urquhart, 2013).

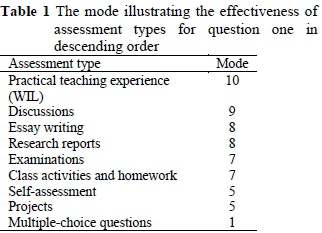

Question one of the questionnaire required of participants to rank assessments based on effect- tiveness, with 1 being the least effective and 10 the most effective assessment type. After the numbers given by participants were coded, the mode of each assessment type was used to rank assessments from the least to the most effective, as shown in Table 1 below.

Questions two to 16 were coded according to a "yes"/"no" nominal scale to determine the mode of each question to gain more in-depth understanding of the assessment types used during the BEd undergraduate degree and how these prepared pre-service teachers for the South African context. In response to these questions the participants needed to indicate whether assessments during their undergraduate degree included authentic classroom experiences; provided clear guidelines and expectations; gave enough time for assessments to be completed; provided feedback; and gave such feedback within two to three weeks after assessment submission.

The quantitative data were used to inform us about confirming and disconfirming cases. Confirming and disconfirming cases are defined by Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom Duan and Hoagwood (2015) as data which, in this study, would confirm that participants were prepared through assessment for the South African schooling context (confirming cases) or disconfirm the preparation of pre-service teachers through assessment for the South African context (disconfirming cases).

Confirming and disconfirming cases allowed us to identify whether participants were adequately prepared through assessment for the South African schooling context during their BEd undergraduate studies. After the quantitative data analysis had been completed, eight participants were selected as being the most confirming or most disconfirming due to the frequency of their responses. For the purpose of this study, the frequency of responses refers to how often a participant answered "yes" or "no" to the questions. Participants answering "yes" to all 15 close-ended, self-administered questions had the highest frequency of "yes" responses, confirming that they were adequately prepared through assessment for the South African context. Alternatively, participants who answered "no" to all close-ended, self-administered questions had the highest frequency of "no" responses, confirming that they were not adequately prepared through assessment. Participants who answered "yes" to some of the questions were adequately prepared through assessment in some areas and inadequately in others, as illustrated in Table 2.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative data were collected using semi-structured questions informed by the data from the quantitative data for one-on-one interviews. Eight participants were asked to indicate their experiences with multiple-choice assessment and self-assessment; what aspects should have been included in their learning; and the guidance provided during their WIL. Self-assessment is an important part of the teaching profession where the pre-service teacher uses reflection to deconstruct concrete experiences from the classroom, along with newly gained information to create meaningful experiences that inform and improve their practice. Thus, leading the pre-service teacher to construct their own knowledge or reality (Goby & Lewis, 2000; Sherwood & Horton-Deutsch, 2012).

All interviews were recorded (with consent) using a recording device and transcribed into a Microsoft Word document for coding (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al., 2014) and interpretative analysis (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). Using a recording device enabled us to give undivided attention to each participant and to listen to the context of each answer while identifying any subtext or hidden meaning(s). The purpose of the qualitative data collection was to gain deeper insight into the factors that made participants feel that they were adequately or inadequately prepared through assessment, while also considering the contextual factors and the role that these play in their preparation.

Qualitative data were analysed using constructivist grounded theory, which uses data collected through observations and interactions, and from materials, to analyse data into units of meaning (Charmaz, 2014). We chose this method of analysis as verbal and non-verbal responses were collected during the data collection phase, meaning that the data were collected using observations (non-verbal responses), interactions (semi-structured questions and responses) and materials (an audio device). Qualitative data relies on abductive reasoning and abductive inference to draw logical conclusions from the data collected (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). Abductive reasoning is used in grounded theory because it allows the researcher to interpret experiences in conjunction with the theoretical framework and draw conclusions about what the participant is expressing about the experiences described. This type of reasoning is then used to compare participants' experiences and to align the conclusions into a common trend or pattern identified among the participants from the raw data (Charmaz, 2014).

The data analysis started by transcribing the raw data into a Word document from the recordings made during the data collection phase. Each transcription required of us to listen to the recording, write down what had been said and listen to the recording again to ensure that the raw data had been captured word for word. In the transcriptions we used the pseudonyms given to each of the participants during the initial quantitative transcription process. Once the data had been transcribed, we included non-verbal responses noted during the interviews. These included changes of pitch, movements, facial expressions and body language (Creswell, 2013).

The transcripts were annotated line by line, with units of meaning added to the transcripts in the form of labels. These included relevant words, phrases, sentences or sections identified during the quantitative data collection phase. Information was coded if it was repeated multiple times during the interviews, stood out from the data collected, was explicitly important in answering the research question or reminded us of a theory or concept discussed in the literature review (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al., 2014). Using more in-depth information obtained by probing (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014), the data deepened the understanding of what pre-service teachers experienced in the South African context and how these authentic experiences led to their views about preparation (Ågerfalk, 2013).

The themes identified in this study included assessment, the preparation of the pre-service teacher for the South African context, and the preparation of pre-service teachers during the BEd undergraduate programme. The analysis of the quantitative and qualitative data suggests that participants felt prepared by assessment but did not feel prepared for the South African context when trying to create an inclusive environment for learners with language and learning barriers and behavioural problems. Furthermore, because of the practical assessment strategies used for preparation purposes, participants became confident in their preparation during the BEd undergraduate degree.

Findings

Assessment Appeared to be Beneficial to Teacher Preparation

To determine their level of mastery, pre-service teachers are assessed using formative assessments, summative assessments and WIL. Assessment tasks given to pre-service teachers were made available at the beginning of the semester. All participants agreed that they were given sufficient time to complete the assessments and that guidelines were generally clear. When these were unclear, students were able to get clarity about the guidelines. In this way, assessments prepared pre-service teachers for future in-service experiences because they were clear about the expectations of the assessments. Findings of this study show that pre-service teachers found all assessment types beneficial, including multiple-choice questions, which were initially the lowest-ranked assessment types.

The findings in relation to assessment are presented by firstly looking at multiple-choice questions followed by WIL and self-assessment.

Multiple-choice Tests were Beneficial and Assisted Participants in Developing their Own Assessment Strategies

Participants all stated that multiple-choice questions assisted them in learning about the theoretical aspects of their modules and, because of the nature of multiple-choice questions, that they had to master this theory to attain a high score. Fuhrman (1996) explains that multiple-choice assessments continue to be used to test students as they have high reliability in testing student knowledge and can cover a broader amount of content than other assessment types. If constructed correctly, diverse skills and abilities can be assessed with this type of assessment. Einig (2013) and Massoudi, Koh, Hancock and Fang (2017) found that using multiple-choice questions as part of a formative assessment strategy improved performance in examinations. By contrast, Fish (2017) argues that multiple-choice questions that test the lower levels of Bloom's taxonomy have little to no benefit for the learner. Hahn, Fairchild and Dowis (2013) found that multiple-choice assessment had no influence on examination performance.

These contradictory viewpoints may arise because not all multiple-choice assessments meet assessment guidelines; these aim to ensure that assessments are reliable and valid in providing an authentic representation of a learner's content mastery. If they do not meet these guidelines, assessments do not serve the purpose originally intended.

Participants raised concerns about poorly structured multiple-choice questions that lead participants to guess the answers or misinterpret the questions. According to Gyllstad, Vilkaitė and Schmitt (2015), poorly structured multiple-choice assessments lead to misrepresentation of results and thus affect the reliability and validity of the assessment type as a measure of learners' level of mastery. D'Sa and Visbal-Dionaldo (2017) emphasise that a large number of high-quality multiple-choice questions should be pre-generated, removing implausible distractors and revised to ensure that this type of assessment meets the assessment guidelines. This can only be done effectively through faculty training. Abdulghani, Ahmad, Irshad, Khalil, Al-Shaikh, Syed, Aldrees, Alrowais and Haque (2015) found that the quality and validity of multiple-choice assessments improved when faculty received training on how to design a multiple-choice assessment to meet learners' needs.

When structured using higher order questioning strategies indicated by Bloom's taxonomy, multiple-choice questions are a beneficial assessment type that can enhance student learning and performance. When poorly structured, however, multiple-choice assessments have little to no positive effect on learner performance and may negatively impact on the learner's grades if s/he becomes confused and tries to guess the answers. The quality of a multiple-choice assessment relies on creating a sound structure and reviewing the items in alignment with the higher-order thinking proposed by Bloom's taxonomy and assessment guidelines while removing implausible distractors. A well-structured multiple-choice question can be an effective assessment type that tests pre-service teachers' theoretical knowledge before moving on to the practical application of this content during WIL.

WIL was Beneficial but not Authentic to the South African Context

WIL was initially indicated as the most beneficial assessment type. However, when questioned further, participants indicated that it was not authentic to the current South African teaching context. They elaborated by stating that it focused on developing pedagogical practices but did not include the full dimensions of the role such as developing classroom management strategies and carrying out administrative and organisational tasks.

WIL provides pre-service teachers with insight into the teaching profession. However, Arends (2011) states that pre-service teachers need to be made aware of the administrative and organisational tasks currently used within the system. Pre-service teachers need to be provided with the opportunity to work through formal governmental documentation and to complete school reports and learner reports that form part of day-to-day work. Pre-service teachers also need to know how to set up assessments and how long it takes to mark these, especially for larger groups. Assessments could be expanded into teaching pre-service teachers how to capture and calculate learners' marks and how to do this in effective and time-saving ways. Harris (2017) indicates that teachers spend relatively little of their time teaching and most of their time inputting data, planning lessons and carrying out other administrative tasks. Philipp and Kunter (2013) explain that more experienced teachers near the end of their careers learn to focus on positive interactions and try to optimise their time while mid-career teachers are often committed to too many tasks; this increases their chances of emotional exhaustion and burnout. Not preparing pre-service teachers for this time-consuming part of their role may be one of the largest factors leading to teacher burnout and exhaustion and to their leaving the profession.

In contrast, Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2017) found that burnout was often associated with job satisfaction, which was dependent on the social climate experienced within the school. Grosemans, Boon, Verclairen, Dochy and Kyndt (2015) note that pre-service teachers cannot be taught everything relevant to the teaching profession within four years and that pre-service teachers need to be aware that their more experienced counterparts are also learning as their own practice develops. Teaching is not static and there is no one-size-fits-all method that can be passed on from one teacher to the next. Hoffman, Wetzel, Maloch, Greeter, Taylor, DeJulio and Vlach (2015) suggest that teaching pre-service teachers needs to involve more than presenting content and techniques in a theoretical manner so that they can use theory to inform their teaching practice. Pre-service teachers could benefit from going to schools for a longer duration in their first three years and begin teaching from their first year so that they can practice applying the theory taught at the institution from the beginning of their studies, rather than waiting until they reach their final year.

Pre-service teachers also need to be taught about the teaching role in its entirety and be given the opportunity to complete formal documentation and reports and carry out marking and other responsibilities that are a time-consuming part of their role. They cannot simply be taught about this in a theoretical manner and WIL should be the platform where they develop - not only their pedagogical expertise, but also their understanding of the role in its entirety. This would provide them with a more authentic experience allowing them to make informed decisions about whether to become a teacher, in turn leading to fewer teachers leaving the profession later in their careers.

Self-assessment is a Beneficial Tool, Promoting Life-long Learning

Novice teachers who participated in this study explained that self-assessment remained an important informal and formal practice after they had completed their BEd undergraduate degrees. According to Fry, Klages and Venneman (2018), self-assessment is not a naturally occurring process and should be taught to all pre-service teachers as it leads to improved classroom instruction and higher levels of learner achievement. Critical reflection enables teachers to deconstruct their contextual experiences and reconstruct these using the newly formed information to improve their practice (Sherwood & Horton-Deutsch, 2012). Beijaard and Meijer (2017) explain that this type of assessment strategy can be a transformative process, enabling personal growth and the development of a professional identity that leads to many advantages for the teacher and learners.

The development of a professional identity is an important part of self-assessment practices. Sööt and Viskus (2015) found that novice teachers were unable to critically reflect on their own practices as they had not developed such an identity and, therefore, did not know enough about themselves to have meaningful and constructive insights into their own practices. The reflection process requires of novice teachers to be able to reflect on multiple levels including their own beliefs, environment, behaviour, competencies, identities and mission. To be effective, reflection on these levels needs to be robust. Khan (2017) found that reflection was more meaningful for experienced teachers than beginner teachers as it is a complex process that needs to be robust enough to incorporate interaction between theory and practice on multiple levels. This robust reflection allows teachers to engage in transformative practices which cannot be achieved through informal reflection.

According to Svojanovsky (2017), self-assessment is a transformative process that should allow pre-service teachers to move from a transmission approach of teaching to an approach that is more interactive and that focuses on teaching for understanding. The study showed that making this shift was very challenging for pre-service teachers as mentor teachers were not able to assist them in this type of reflective practice, because the mentor teachers themselves were often unable to align with these new teaching approaches.

The findings illustrate that multiple-choice assessments benefited pre-service teachers in their undergraduate degree by showing them how multiple-choice questions should not be structured and taught pre-service teachers how to improve their own assessments. WIL and self-assessment were also seen as very beneficial as pre-service teachers found that this helped them to assimilate into the role of the teacher through contextually rich experiences. However, it should be noted that more exposure to teaching earlier on in their studies could be highly beneficial. The findings on assessment meet the first objective in that assessment is beneficial in preparing pre-service teachers.

WIL provided pre-service teachers with an interface between what is assessed at university and the experiences at school when focusing on the pedagogical practices of teachers. However, WIL needed to be more authentic by preparing teachers for the administrative and organisational tasks that make up a large part of their roles. The finding shows that WIL did not completely meet the secondary objective of the study, and institutions should consider the type of schools that pre-service teachers attend and how to better expose them to the administrative and organisational aspects that form a large part of the teaching role.

The ethical issues that arose during this study was ensuring that participants signed the informed consent prior to taking part in research. We also needed to ensure that participant details remained confidential and anonymous throughout the study.

Future research areas should focus on what assessments in WIL could assist in preparing pre-service teachers for the administrative and organisational aspects of teaching, the authentic and contextual experiences gained at different schools and how to prepare lecturers for the development of well-structured multiple-choice questions. These posed a challenge at times as social media creates a more informal channel of communication, which should be considered for future research.

Conclusion

This study provided insight into the preparation of pre-service teachers through assessment within the South African context. Evidence from this study suggest that pre-service teachers were prepared, however, also highlighted aspects where assessment was lacking. Institutions should focus on providing pre-service teachers with authentic experiences that include the administrative and organisational aspects of teaching while ensuring that the experience is contextually rich by exposing pre-service teachers to learners of difference genders, races, religions, cultures, languages and/or disabilities. Institutions should also consider the duration of teaching experience to ensure that pre-service teachers are provided with a sufficient amount of time to implement the theory taught at the institution in the classroom. Lastly, lecturer training on assessment strategies is required to ensure that well-structured multiple-choice questions are administered and other assessments types may be structurally improved.

Authors' Contributions

NI as student and KS as supervisor collaborated on this article as an output on the completion of a master's degree in Education.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 30 May 2018; Revised: 16 October 2019; Accepted: 3 December 2019; Published: 31 August 2020.

References

Abdulghani HM, Ahmad F, Irshad M, Khalil MS, Al-Shaikh GK, Syed S, Aldrees AA, Alrowais N & Haque S 2015. Faculty development programs improve the quality of multiple choice questions items' writing. Science Reports, 5:9556. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09556 [ Links ]

Ågerfalk PJ 2013. Embracing diversity through mixed methods research. European Journal of Information Systems, 22(3):251-256. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2013.6 [ Links ]

Aragon A, Culpepper SA, McKee MW & Perkins M 2014. Understanding profiles of preservice teachers with different levels of commitment to teaching in urban schools. Urban Education, 49(5):543-573. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0042085913481361 [ Links ]

Arends F 2011. Teacher shortages? The need for more reliable information at school level. Review of Education, Skills Development and Innovation, November:1-4. Available at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/2702/RESDI%20newsletter,%20November%202010%20issue.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2020. [ Links ]

Bakx A, Baartman L & Van Schilt-Mol T 2014. Development and evaluation of a summative assessment program for senior teacher competence. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 40:50-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.11.004 [ Links ]

Beijaard B & Meijer PC 2017. Developing the personal and professional in making a teacher identity. In DJ Clandinin & J Husu (eds). The Sage handbook of research on teacher education (Vol. 1). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Brookhart SM 2004. Assessment theory for college classrooms [Special issue]. New Directions for Teaching & Learning, 2004(100):5-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.165 [ Links ]

Brown AL, Lee J & Collins D 2015. Does student teacher matter? Investigating pre-service teachers' sense of efficacy and preparedness. Teaching Education, 26(1):77-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2014.957666 [ Links ]

Charmaz K 2014. Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Christoforidou M, Kyriakides L, Antoniou P & Creemers BPM 2014. Searching for stages of teacher's skills in assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 40(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.11.006 [ Links ]

Cornish L & Jenkins KA 2012. Encouraging teacher development through embedding reflective practice in assessment. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2):159-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.669825 [ Links ]

Council of Higher Education 2011. Work-integrated learning: Good practice guide (HE Monitor No. 12). Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at http://cctprojects.co.za/wbeproject/documents/WIL/Higher_Education_Monitor_12.pdf. Accessed 27 April 2020. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2013. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training 2015a. Higher Education Act (101/1997) and National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Policy on minimum requirements for programmes leading to qualifications for educators and lecturers in adult and community education and training. Government Gazette, 597(38612):1-48, March 27. Available at http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/Policy%20on%20minimum%20requirements%20for%20programmes%20leading%20to%20qualification.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training 2015b. National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Revised policy on the minimum requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Government Gazette, 596(38487):1-72, February 19. Available at http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/National%20Qualifications%20Framework%20Act%2067_2008%20Revised%20Policy%20for%20Teacher%20Education%20Quilifications.pdf. Accessed 27 April 2020. [ Links ]

Dowden BH 2017. Logical reasoning. Sacramento, CA: California State University Sacramento. Available at https://www.csus.edu/indiv/d/dowdenb/4/logical-reasoning-archives/logical-reasoning-2017-12-02.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2020. [ Links ]

D'Sa JL & Visbal-Dionaldo ML 2017. Analysis of multiple choice questions: Item difficulty, discrimination index and distractor efficiency. International Journal of Nursing Education, 9(3):109-114. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-9357.2017.00079.4 [ Links ]

Du Plooy-Cilliers F, Davis C & Bezuidenhout RM 2014. Research matters. Claremont, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Einig S 2013. Supporting students' learning: The use of formative online assessments. Accounting Education, 22(5):425-444. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2013.803868 [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P, Nel M, Nel N & Tlale D 2015. Enacting understanding of inclusion in complex contexts: Classroom practices of South African teachers. South African Journal of Education, 35(3):Art. # 1074, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n3a1074 [ Links ]

Faez F 2012. Diverse teachers for diverse students: Internationally education and Canadian-born teachers' preparedness to teach English language learners. Canadian Journal of Education, 35(3):64-84. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/canajeducrevucan.35.3.64.pdf?casa_token=kFmhBsiWQqQAAAAA:5rBgS7fYXVonP-5F_rUfDkH5Y7wQwvqP_DVKkY_dVjbsYoAyjndqIadvrm4e8K39JN-MYpI1HDCV0wzzfI8wjqf1PYNt2qzt3IheieTT7L4BCU8d_KNRjg. Accessed 5 April 2020. [ Links ]

Fish LA 2017. The value of multiple choice questions in evaluating operations management learning through online homework versus in-class performance. Business Education Innovation Journal, 9(2):103-109. [ Links ]

Fry J, Klages C & Venneman S 2018. Using a written journal technique to enhance inquiry-based reflection about teaching. Reading Improvement, 55(1):39-46. [ Links ]

Fuhrman M 1996. Developing good multiple-choice test and test questions. Journal of Geoscience Education, 44(4):379-384. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-44.4.379 [ Links ]

Goby VP & Lewis JH 2000. Using experiential learning theory and the Myers-Briggs type indicator in teaching business communication. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 63(3):39-48. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F108056990006300304 [ Links ]

Grosemans I, Boon A, Verclairen C, Dochy F & Kyndt E 2015. Informal learning of primary school teachers: Considering the role of teaching experience and school culture. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47:151-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.011 [ Links ]

Gulikers JTM, Biemans HJA, Wesselink R & Van der Wel M 2013. Aligning formative and summative assessments: A collaborative action research challenging teacher conceptions. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 39(2):116-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.03.001 [ Links ]

Gyllstad H, Vilkaitė L & Schmitt N 2015. Assessing vocabulary size through multiple-choice formats: Issues with guessing and sampling rates. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 166(2):278-306. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.166.2.04gyl [ Links ]

Hahn W, Fairchild C & Dowis WB 2013. Online homework managers and intelligent tutoring systems: A study of their impact on student learning in the introductory financial accounting classroom. Issues in Accounting Education, 28(3):513-535. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50441 [ Links ]

Harris C 2017. 'When teachers spend more time on planning than the teaching, we know we have a problem'. TES Global, 1 November. Available at https://www.tes.com/news/when-teachers-spend-more-time-planning-teaching-we-know-we-have-problem. Accessed 24 May 2020. [ Links ]

Hoffman JV, Wetzel MM, Maloch B, Greeter E, Taylor L, DeJulio S & Vlach SK 2015. What can we learn from studying the coaching interactions between cooperating teachers and preservice teachers? A literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52:99-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.09.004 [ Links ]

Khan MI 2017. Reflection and the theory-practice conundrum in initial teacher education in the UK. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 11(1):64-71. Available at https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/54233564/Reflection_and_the_Theory_Practice_Conundrum_in_Initial_Teacher_Education_in_the_UK.pdf?1503582642=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DReflection_and_the_Theory_Practice_Conun.pdf&Expires=1599141715&Signature=Us4eeXsU5JEDyPgaN-f4UeUW5ZwInzKw1EywIAEZsUzMedWPRPeXBk5dAWMed4pPxALndoVlTcJNJPMJi1QuXljuTKBcO0bGO76U9SO1hJaCxHL6hol1HyUs-heUfK~mcso0jx2XhULIF8DQYLPnxyv4mzu8yKXB~2x8dMjz2vqRmwFDIXARBQS1ao8ElSIL5OHilqPf9GhaI33MA27YRUlhf7hr4CS7BPaScWzuN~nvWuXgZjOnoERDC-BwfBBVko1lQdT4AnBFOMoREIYfEZjSgCr32TR1fb9dKHeJI~SRkeMOwqy5EdrZyg1MQ9Bh51TzhLNh6oneAGQmNqPPPg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. Accessed 3 April 2020. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick JD & Kirkpatrick WK 2016. Kirkpatrick's four levels of training evaluation. Alexandria, VA: ATD Press. [ Links ]

Kolb DA 2015. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Landsberg E, Krüger D & Swart E (eds.) 2016. Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspective (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Lee J, Tice K, Collins D, Brown A, Smith C & Fox J 2012. Assessing student teaching experiences: Teacher candidates' perceptions of preparedness. Educational Research Quarterly, 36(2):3-19. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1061946.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2020. [ Links ]

Massoudi D, Koh SK, Hancock PJ & Fang L 2017. The effectiveness of usage of online multiple choice questions on student performance in introductory accounting. Issues in Accounting Education, 32(4):1-17. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-51722 [ Links ]

Matsko KK & Hammerness K 2014. Unpacking the "urban" in urban teacher education: Making a case for context-specific preparation. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(2):128-144. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487113511645 [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S 2014. Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Nel N, Nel M & Hugo A (eds.) 2012. Learner support in a diverse classroom: A guide for foundation, intermediate and senior phase teachers of language and mathematics. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N & Hoagwood K 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42:533-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [ Links ]

Philipp A & Kunter M 2013. How do teachers spend their time? A study on teachers' strategies of selection, optimisation and compensation over their career cycle. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.04.014 [ Links ]

Piaget J 2013. The principles of genetic epistemology (Selected works Vol. 7). Translated by W Mays. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Reddy C, Le Grange L, Beets P & Lundie S 2015. Quality assessment in South African schools. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta. [ Links ]

Schenck J & Cruickshank J 2015. Evolving Kolb: Experiential education in the age of neuroscience. Journal of Experiential Education, 38(1):73-95. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1053825914547153 [ Links ]

Sherwood GD & Horton-Deutsch S 2012. Reflective practice: Transforming education and improving outcomes. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International. [ Links ]

Skaalvik EM & Skaalvik S 2017. Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Social Psychology of Education, 20:15-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9363-9 [ Links ]

Sööt A & Viskus E 2015. Reflection on teaching: A way to learn from practice. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191:1941-1946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.591 [ Links ]

Svojanovsky P 2017. Supporting student teachers' reflection as a paradigm shift process. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66:338-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.001 [ Links ]

Sztajn P, Confrey J, Wilson PH & Edgington C 2012. Learning trajectory based instruction: Toward a theory of teaching. Educational Researcher, 41(5):147-156. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0013189X12442801 [ Links ]

Tran TT 2016. Pragmatism and constructivism in conducting research about university-enterprise collaborate in the Vietnamese context. In 1st International Symposium on Qualitative Research (ISQR) Proceedings (Vol. 5). Oporto, Portugal. Available at https://proceedings.ciaiq.org/index.php/ciaiq2016/article/view/1048/1021. Accessed 31 May 2020. [ Links ]

Tuytens M & Devos G 2011. Stimulating professional learning through teacher evaluation: An impossible task for the school leader? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5):891-899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.02.004 [ Links ]

Urquhart C 2013. Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Verberg CPM, Tigelaar DEH & Verloop N 2015. Negotiated assessment and teacher learning: An in- depth exploration. Teaching and Teacher Education, 49:138-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.007 [ Links ]

Waggoner J & Carroll JB 2014. Concurrent validity of standards-based assessments of teacher candidate readiness for licensure. Sage Open, 4(4):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244014560545 [ Links ]

Walton E, Nel NM, Muller H & Lebeloane O 2014. 'You can train us until we are blue in our faces, we are still going to struggle': Teacher professional learning in a full-service school. Education as Change, 18(2):319-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823206.2014.926827 [ Links ]

Weinstein N 2013. Experiential learning. Research starters: Education. [ Links ]

Wiliam D 2011. What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1):3-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.001 [ Links ]

Woolfolk Hoy A 2014. Educational psychology (12th ed). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]