Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n3a1836

ARTICLES

Critical skills for deputy principals in South African secondary schools

Jan B. Khumalo; C.P. Van der Vyver

School of Professional Studies in Education, Faculty of Education, North West University, Mahikeng, South Africa. jan.khumalo@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The development of critical skills for deputy principals is a matter which deserves attention, owing to the critical role which deputy principals are expected to play in school management. However, this area of research is neglected and has received limited attention in the literature that focuses on school leadership development. In this vein, the critical skills needed by deputy principals should be identified in order to suggest measures or programmes to develop the skills. Moreover, the role of deputy principals in school management and leadership brings expectations which need to be met through effective performance. In order for deputy principals to perform their duties as expected, they need proper skills and professional development. The purpose of the study reported on here was to identify and establish the extent of the need of critical skills for deputy principals in secondary schools. In order to achieve the aim of the study, a quantitative survey was adopted to collect the data. The paradigm used was the post-positivist paradigm. The participants in the study were 157 secondary school deputy principals from one province in South Africa. Data were gathered using a standardised questionnaire and analysed by means of descriptive statistical techniques, including frequencies, means and percentages. The results reveal that deputy principals in the studied sample needed positional-awareness or role-awareness, technical, socialisation and self-awareness skills in order to perform their duties effectively. We recommend a preparation programme, mentoring and ongoing professional development to develop these skills for deputy principals in order to empower them to contribute to the attainment of quality education.

Keywords: critical skills; deputy principals; mentoring; professional development; school management team; secondary schools; South Africa

Introduction

The current discourse about the imperative to transform school leadership practices presupposes the empowerment of deputy principals to enable them to perform their duties effectively. The justification for the empowerment of deputy principals stems from the need to employ deputy principals who are envisaged by the Department of Basic Education to contribute to improving the quality of school management and leadership. According to their job description, deputy principals play a supportive role to the principal and are accountable for the improvement of the performance of their schools. In order to fulfil this crucial role, deputy principals require critical skills to enable them to carry out their duties and responsibilities as expected. At the same time, the identification of critical skills for deputy principals is a matter that merits more research in light of the discovery of an empirical gap in this field of study.

There is an inadequate body of knowledge on deputy principalship in South Africa (Mailula, 2006; Potgieter, 1990). Globally, some studies (e.g. Barnett, Shoho & Okilwa, 2017; McDaniel, 2017; Petrides, Jimes & Karaglani, 2014) have brought deputy principalship into the spotlight. In addition, some research work corroborates the view that deputy principals need appropriate knowledge, skills and habits to perform their duties and responsibilities effectively (Dodson, 2015; Lile, 2008; Nieuwenhuizen & Brooks, 2013).

The deputy principal is part of the school management team (SMT), which has the statutory duty to undertake the professional management of schools. This dispensation suggests a more prominent curriculum and instructional leadership role for the deputy principal and an acknowledgement of the urgent need to equip deputy principals with the requisite critical skills.

Policy documents that contain prescriptive measures on the expected levels of performance for deputy principals include the Personnel Administrative Measures (PAM) document (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2016) and the Strategy to Improve School Management and Governance in Schools (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2017). To complement clear policies and guidelines on expected levels of performance of school leaders, such as deputy principals, the Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa (2017:7) reinforces the need for the skills development of deputy principals by arguing that "incompetent middle managers will weaken the management teams of schools." Similarly, the "main contributor of underperformance and dysfunctionality in schools is related to the capacity, competence and nature of the school management team" (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2017:4). In the same manner, school leaders or deputy principals need appropriate administrative and management skills to be able to function optimally within the context of national development.

The identification of skills for deputy principals as part of their professional development is also highlighted in the National Development Plan 2030 and Vision 2025. These policy documents reveal the need to have "highly skilled individuals" and accentuate the urgent need for lifelong learning and continuous professional development to build the capabilities of individuals such as deputy principals. In addition, the priorities regarding the improvement of school management include the development of human capacity (National Planning Commission, Republic of South Africa, 2012). In order to play their envisaged role as part of the SMT that will contribute to the improvement of learning outcomes, the skills needed by deputy principals should be identified so that these can be developed.

The contribution of this study towards the scholarship on deputy principalship is not only significant in the South African context but also for a global audience. Studies conducted on deputy principalship in other parts of the world accentuate the need for the professional development of deputy principals (Barnett et al., 2017; Harris, Muijs & Crawford, 2003; Petrides et al., 2014). Scholars interested in the deputy principalship world-wide will relate to the findings of the study, which seem to be similar across diverse contexts.

In an attempt to address the problem implied in the preceding paragraphs, the question that guided this research was formulated as follows: What are the critical skills that deputy principals need to improve their performance? To answer the research question, the investigation sought to identify the critical skills needed by deputy principals to perform their duties effectively and the extent to which these skills were needed. The consulted literature revealed the critical skills needed by deputy principals. From there, a standardised questionnaire and several statistical techniques were used to determine the extent to which the skills were needed.

Conceptual-theoretical Framework

This paper is premised on the argument that deputy principals need to be equipped with critical skills to enable them to perform their duties effectively. An understanding of critical skills for deputy principals can be constructed through the three-skill theory (Daresh, 2006; Daresh & Alexander, 2016; Daresh & Arrowsmith, 2003; Daresh & Playko, 1992, 1994), which unpacks critical skills for school leaders. The three-skill theory teaches that the skills that are needed by school leaders such as deputy principals can be categorised into technical, socialisation and self-awareness skills. A more recent study conducted in South Africa added a fourth category of skills, namely positional-awareness skills (Khumalo, Van der Westhuizen, Van Vuuren & Van der Vyver, 2017) or what Daresh and Alexander (2016) labelled role-awareness skills. Each of these clusters of skills comprises a subset of skills that are critically needed by deputy principals for the performance of their duties. In the paragraphs that follow, the three clusters of skills are scrutinised and the use of the theory as the metaphorical frame on which this study was built, is justified.

Technical skills

According to Damooei, Maxey and Watkins (2008, in Nasir, Ali, Noordin & Nordin, 2011:10) technical skills refer to "skills that require a combination of specific knowledge and skills of the work that needs to be done in order to achieve the performance target." Similarly, technical skills mean "technical procedures or practical tasks that are typically easy to observe, quantify and measure" (Nasir et al., 2011:10). In fact, technical skills for deputy principals are skills that are tangible, specific and usually teachable, such as, inter alia, how to budget or how to evaluate the performance of teachers and departmental heads.

Additionally, technical skills are regarded as those skills that are related to the specific field of study, preparation, or even profession. School managers and leaders constantly need to upgrade their knowledge to keep abreast of the latest developments in their field. To develop their technical skills, deputy principals can attend courses, seminars, conferences or tutorials that are specifically targeted to develop these skills, or they can even consult the literature on skills development. Technical skills can be regarded as "the ability to perform work in a technically competent manner and to monitor the work in an independent and critical manner" (Abd. Rahman, 2000:10).

In addition, the following technical skills surfaced from the literature: the capacity to delegate and empower others, to develop networks, to implement change management (Cranston, Tromans & Reugebrink, 2004), to apply communication skills, to use techniques for improving the curriculum and instruction, to work with teams, to develop the curriculum and to apply time management (Weller & Weller, 2002). Arguably, deputy principals need these skills to understand how to do their work.

Socialisation skills

Socialisation skills or "social skills are skills that allow a person to interact and communicate with others and to act appropriately in given social contexts" (Little, Swangler & Akin-Little, 2017:9). In the school context, social or socialisation skills imply those skills that enable the deputy principal to interact with the members of the SMT, the staff, the learners, the school governing body (SGB) and the entire school community, and to communicate effectively with them. Further definitions of social or socialisation skills also reveal that these are "the skills that are used to communicate and interact with one another, both verbally and nonverbally through gestures, body language and personal appearance" (Little et al., 2017:9). Social or socialisation skills enable school leaders to develop an awareness of what other people will expect from them and the standards of behaviour they have to uphold.

In concurrence with the social or socialisation skills already generated, the following skills have been documented by Weller and Weller (2002:25): "people skills, working with teams, the ability to work with the community and knowing the informal leaders and networks at the school." In addition, skills such as "being inspiring, envisioning change for the school, demonstrating strong interpersonal people skills and managing uncertainty for the self, have also been identified" (Cranston et al., 2004:237-238).

Social or socialisation skills can be understood as "skills that enable individuals to function competently when performing social tasks" (Cook, Gresham, Kern, Barreras, Thornton & Crews, 2008:133). In a school management-leadership context, social tasks may have to do with the deputy principal's interaction with stakeholders, which requires them to master particular social skills. Little et al. (2017:10) suggest that "social skills involve specific learnt behaviour, comprise both initiation and response behaviours and entail interactions with others." These skills are assumed to be "socially reinforced and denote skills that are context specific" (Little et al., 2017:10). Although the definitions of social skills may be different, there seems to be consensus on how social skills are developed (Little et al., 2017). For deputy principals, Owen-Fitzgerald (2010:iii) proposes what he terms "a variety of professional development training" to develop their skills. Among the kinds or types of professional development activities put forward, is mentoring, which can be useful to enable the deputy principal to learn socialisation skills from an experienced mentor.

Self-awareness skills

Self-awareness is "a process of learning through and from experience and gaining new insights of self and or practice" (Greene, 2017:1). In the same vein, self-awareness skills are defined as "a set of coping and self-management skills that increase self-efficacy" (Hatami, Ghahremani, Kaveh & Keshavarzi, 2016:89). In fact, "people who have a high degree of self-awareness recognise how their feelings affect themselves, other people and their job performance" (Goleman, 2004:84). In the school environment where there could be conflict and tension, a deputy principal with self-awareness and emotional intelligence will be honest with him or herself and act in the best interest of the learners, the school and the education system. Moreover, Goleman (2004:82) argues that "emotional intelligence is the sine qua non (necessary or essential condition) of leadership." That is why "effective leaders are distinguished by a high degree of emotional intelligence, which includes self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills" (Goleman, 2004:82).

The significance of the acquisition of self-awareness skills for deputy principals is that self-awareness is viewed as an interrelated set of thoughts and experiences that make people look into themselves and discover their hidden selves (Mohammadiary, Sarabi, Shirazi, Lachinani, Roustaei, Abbasi & Ghasemzadeh, 2012; Safarihalavi, 2012). Self-awareness means prioritising goals and trying to reach them flexibly, without being afraid of failure (Abbasi & Fani, 2006). In order to play a more prominent role in instructional leadership, deputy principals are required to understand their own identity as part of the SMT and, accordingly, fulfil their management and leadership roles.

Role-awareness or positional-awareness skills

Role-awareness or positional-awareness skills refer to the "demonstration of knowing what the job is all about and how it affects the individual person" (Daresh & Arrowsmith, 2003:14). The development of role-awareness or positional-awareness skills also entail adopting measures that are geared towards the development of the skills of deputy principals. The deputy principal's role-awareness or positional-awareness skills entail "an awareness of what it means to possess organisational authority and power" (Khumalo et al., 2017:204). Acquiring role-awareness skills or positional-awareness skills, which are related to a leader's own identify, is necessary to understand how the leadership capability of deputy principals can be enhanced by developing their role-awareness or positional awareness skills.

Unpacking the concept of role-awareness or positional-awareness further, makes an understanding of the concept pertinent for the deputy principal. In other words, the meaning of role-awareness or positional-awareness skills relates to how a leader such as a deputy principal should know him or herself. Accordingly, people who have role-awareness or positional-awareness skills are honest with themselves and with others (Goleman, 2004).

Daresh and Arrowsmith (2003) offer advice on how school leaders such as deputy principals can develop their positional-awareness or role-awareness skills. Activities that are suggested to assist deputy principals in the development of critical skills include the identification of a mentor to provide feedback about the development of the deputy principal; the crafting and periodical review of an educational philosophy; working with a colleague who will observe their work and report on observed performance; and considering how to deal with personal stress (Daresh & Arrowsmith, 2003). The position of a deputy principal who understands and uses the position effectively can assist to contribute to overall effective management and improvement of learning outcomes.

Methodology

Research Aim

The aim of the study was to establish the critical skills that deputy principals need in the daily performance of their duties and to ascertain the extent to which the skills were needed. As a result, recommendations were made for the development of skills for deputy principals by means of a professional development programme.

Research Design

This study was in the form of a quantitative non-experimental survey, which was framed within the post-positivist paradigm. We preferred the post-positivist paradigm because we believed that the skills needed by deputy principals could be measured. In this vein, the extent to which the skills were needed was measured using a standardised instrument. In order to align the paradigm to the method adopted for the study, a survey was used to collect data from the participants.

Population and Sampling

The participants who took part in the study were a population of deputy principals of secondary schools in one province of South Africa. Initially, the sampling technique used for the study was a census sample, but this sampling technique was unsuccessful because the return rate was too low. Subsequently, the researchers used a convenient sample of secondary school deputy principals who were attending their union conference. Owing to the difficulties encountered with the administration of the questionnaire in the province, we conducted the study among participants to whom we had easy access. The deputy principals were from schools representative of the demographics of South Africa. The participants included new and experienced deputy principals in secondary schools. Two hundred questionnaires were administered to the respondents. A total of 157 (78.5%) questionnaires were returned and used for data analysis. The overall response rate comprised 42% of all secondary school deputy principals in the province. Consistent with standard research protocol, we were wary to generalise the results of the research to the whole population of deputy principals owing to the sampling strategy that was used.

Ethical Aspects

Permission to conduct this research was obtained from the Department of Basic Education in the province. As the research unfolded, permission was also sought from a teacher union to administer questionnaires to their members who were attending a union conference. The questionnaire was administered to secondary school deputy principals who attended the conference as delegates. The research was also approved by the ethics committee of the university under whose auspices it had been conducted. Every questionnaire was accompanied by a cover letter in which the aims of the research were explained. The anonymity of the respondents was assured. The respondents were under no obligation to complete the questionnaire and could withdraw from the research at any time. The respondents also agreed to participate in the study.

Data Collection

The data for the research were gathered by means of a standardised questionnaire developed by Khumalo et al. (2017). In an attempt to avoid redundancy, we argued that this questionnaire (the Professional Development Needs Analysis Questionnaire for Deputy Principals [PDNAQ]), was the only context-specific instrument that we could find and use for data collection for this research. The questionnaire consisted of 85 items and was constructed from the theoretical constructs of skills that were identified from the literature and the PAM document (Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa, 2016). The PAM document highlights the job description of the deputy principal and inherently reveals critical areas in which they might need skills to perform effectively. The questionnaire was based on the original questionnaire, which was developed for new principals by Legotlo (1994). In view of the fact that Legotlo's (1994) questionnaire was developed a while ago and under different circumstances and in a different context, it was adapted, updated, refined and validated for this study.

Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire used for the study was standardised and its validity and reliability were determined. The questionnaire consisted of structured Likert-type items with four response options ranging from "to almost no extent" to "to a large extent." Both the confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses were used and Cronbach's alpha values were calculated to ensure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire (see Khumalo et al., 2017:198-199). The analyses ascertained the validity of the questionnaire while Cronbach's alpha values, which were higher than 0.60, confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire. When used for the study, the questionnaire showed that it measured what it was supposed to measure. All aspects of its construction were given due regard, and its design passed the litmus test of the normative design of quantitative survey questionnaires.

Data Analysis

The data collected for the study were analysed by means of descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means and percentages. The data analysis process sought to determine the extent to which the critical skills that were identified were needed by deputy principals. The ranking of the skills in the data analysis followed the procedure of starting from the lower level moving up to the higher level of the ranking scale used. The constructs and items with mean scores of 2.5 and higher were regarded as critical skills for deputy principals, while those with a lower mean score were regarded as those that are not urgently needed by deputy principals. The results of the study are presented in the next paragraph, followed by a detailed discussion of the implications of the findings.

Results

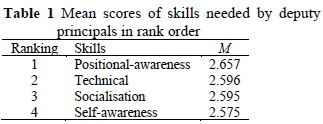

The results of the study presented in this section reveal critical skills for deputy principals who participated in the study and were determined by the ranking of their mean scores. The ranking of the skills was undertaken by computing the mean score of each cluster of skills and the individual items in each cluster of skills. For reporting purposes, the skills with mean scores higher than 2.5 were regarded as critical skills for deputy principals and these are reported in this article. The results of the research show that the sampled deputy principals needed positional-awareness or role-awareness, technical, socialisation and self-awareness skills. The overall mean scores of critical skills needed by the deputy principals are reported in Table 1.

In addition to the overall mean scores of each cluster of skills, the mean scores of the individual skills items are reported on in Table 2. The mean scores of both the clusters of skills and the individual items are highlighted below.

Discussion

It was anticipated that the empirical part of the study would either corroborate what was found in the literature or reveal new knowledge. To some extent, the results corroborated the findings from the literature review, but there were some exceptions, which are highlighted in the presentation of the results.

Despite such exceptions, the findings seem to concur with the argument made in the literature about the urgent need for the skills development of deputy principals. For example, Nieuwenhuizen and Brooks (2013) explain that deputy principals need preparation and training to play an effective role as "an integral and indispensable part" (Hausman, Nebeker, McCreary & Donaldson, 2002:136) of the SMT. This view is reinforced by the proposition that deputy principals should possess "appropriate knowledge, skills, and habits of the mind" (Oliver, 2005:90) to perform their duties effectively. As pointed out in this article, the appropriate knowledge, skills and habits of the mind could be encapsulated in the critical skills for the deputy principals that were detected in this study. Although reference was made to what the literature review uncovered, we acknowledge the limitations of the sample used which constrain the generalisation of results. We also argue that the results do provide useful pointers for future professional development of deputy principals in different contexts.

Positional or Role-awareness Skills

We discovered that the sampled deputy principals needed an awareness of their position or role, which indicates how they can use the power and authority that they have. By virtue of their position as the "second in command" in schools, deputy principals have inherent authority, which they can and must be able to use properly to get the job done and to fulfil their supportive role to the principal. One of the duties of the deputy principal is liaison with internal and external stakeholders. Knowledge of, and skills in galvanising the community to be involved in the development of the school is a crucial aspect of the use of organisational power and authority. In similar vein, deputy principals should understand the power relations in the management echelon of the Department of Basic Education so that they can act appropriately.

In the absence of the principal, the deputy principal is expected to be in charge of the school. While executing this crucial function, the deputy principal has to be bold to use his or her power and authority within the scope of his or her duties to ensure the efficient running of the school. For example, the deputy principal should not feel helpless and say that teachers refuse to attend classes when the principal is not present. If need be, he or she must use his or her power and authority to coerce those who do not want to do their work to ensure effective teaching and learning. Concomitant to the use of power and authority is the notion of ac- countability for one's management actions - something that deputy principals should take cognisance of.

Technical Skills

Deputy principals need technical skills that will empower them with the knowledge of how to do their jobs properly. The technical skills identified in this study show that the sampled deputy principals needed some specific knowledge to help them to proverbially "balance at the top of the greasy management pole." Arguing in favour of the acquisition of technical skills, the study resonates with part of the vision of the Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa (2017:2) to develop "appropriate administrative skills and professional education management competencies by school leaders." Basic technical skills such as time tabling, organising meetings, drafting a budget, among other aspects of general school administration, need to be developed. In addition, deputy principals need knowledge of education law to ensure that they do not act in a judicially incorrect manner.

Daresh and Alexander (2016) theorise that new school leaders regard technical and managerial skills as crucial upon assumption of duty. Therefore, these skills need to be developed to enable them to survive the early years of deputy principalship. In contrast to Daresh and Alexander's (2016) findings, South African deputy principals who participated in the study seemed to prioritise positional-awareness or role-awareness skills.

Social or Socialisation Skills

The deputy principal functions within a school as a social system. Therefore, the acquisition of socialisation skills is crucial to ensure that cordial working and social relationships are established with key partners in education. The relationship with officials from the Department of Basic Education such as circuit managers, subject advisors and district officials is a necessary pre-requisite to achieve the objective of effective teaching and learning. In order to ensure that deputy principals receive the necessary in-service support, critical socialisation skills are necessary to cement relationships in the schooling sector.

Another key focus area regarding the development and use of socialisation skills is building positive relationships with organisations in the school community. Once relationships with community organisations are cordial, various structures that are interested in the school will avail themselves of the opportunity to participate in school activities. Socialisation skills will also enable deputy principals to understand the limitations of their scope of work described in the job description.

Deputy principals need strong human relations skills which will enable them to embrace colleagues who are different and to treat them fairly. The diversity of schools today requires school leaders such as deputy principals who understand that human beings are not machines and that when one manages and leads them, one needs to be sensitive to their particular circumstances.

The establishment of positive relationships with community organisations and mobilising the community to support the school requires a socially competent deputy principal. To be able to develop their socialisation skills, deputy principals may adopt techniques such as understanding the school community, and appreciating the internal and external realities of the school (Daresh & Alexander, 2016). Likewise, Little et al. (2017) remark that socialisation skills enable one to interact with others and act appropriately in given social contexts.

Self-awareness Skills

Self-awareness skills are skills that reveal how much deputy principals know about their own strengths and weaknesses. To understand their own personalities can enable deputy principals to manage people better. In a school context, deputy principals manage people who report to them such as departmental heads, teachers, non-teaching staff and even learners. Again, in the management of these people, knowledge of the leadership role may contribute to the transformation of the school into a thriving learning organisation.

The ability of deputy principals to view themselves in light of how they are viewed by the public as role models for learners is a key component of self-awareness. Deputy principals with high self-awareness normally possess a fervent desire to make a difference in the lives and careers of learners. Armed with a knowledge of their biases, strengths and weaknesses, deputy principals will be able to assist teachers who need help with their teaching duties. A deputy principal who is aware of his or her own unique personality will understand the individuality and uniqueness of colleagues and will assist them when they need assistance with their work. This intervention in the work of colleagues who need help will enable deputy principals to empathise with colleagues and identify and help colleagues who need help.

The tendency to reflect on their own work is necessary for deputy principals to improve their own practice and to meet the expectations of both the public and the employer, regarding their performance and conduct in the school. Self-reflection has proven to be a vital part of self-awareness because it entails self-introspection and self-criticism. Self-awareness can be viewed as the process where a person focuses attention on the self and processes private and public self-information. The self-reflection activity is important for a deputy principal who must manage and lead people at a school.

Self-awareness for the deputy principal implies "a process of learning through and from experience and gaining new insights of self and/or practice" (Greene, 2017:1). Self-reflection as a component of self-awareness has inherent advantages to build competence, prevent burnout and create life-long learning of professionals (Finlay, 2008; Urdang, 2010; Yip, 2006). Similarly, deputy principals who are aware of who they really are will strive to be competent, be satisfied in their role, and participate in on-going professional development activities. To enhance deputy principals' self-awareness, the following activities are suggested (Daresh & Alexander, 2016): deputy principals may identify a personal mentor in their area or district to provide feedback on their career development and generate a statement of personal professional values.

Conclusion

This research revealed how the three-skill theory can be applied to the skills development of the sampled deputy principals, thereby contributing to the body of knowledge on their professional development. Although the three-skill theory was identified from the literature and underpinned the theoretical framework of the study, the fourth skill (positional-awareness skill) as identified by the study of Khumalo et al. (2017), was also confirmed in this study. As a dearth of literature existed on the skills development of deputy principals and their overall professional development, this study undoubtedly contributed to the expansion of knowledge in the field.

The methodological benefit of this study lies in identifying critical skills that deputy principals who took part in the study needed and confirming the extent to which these skills were critically needed. Moreover, the results provide knowledge about the clusters of skills, namely positional-awareness or role-awareness, technical, socialisation and self-awareness skills that deputy principals need to fulfil their roles. The Department of Basic Education will benefit from this research by noting and possibly considering the skills development measures for deputy principals that are suggested in this research. We argue further that future professional development endeavours could infuse the development of the skills into their programmes. The research also sheds light on the kind of deputy principal envisaged to lead and manage schools in the context of national development. Measures such as a preparation programme, mentoring and ongoing professional development are recommended to develop the critical skills that deputy principals need.

Lastly, it is recommended that future research should focus on adequate preparation and continuous professional development of deputy principals using the critical skills identified in this research.

Authors' Contributions

JBK wrote the manuscript and generated the quantitative data for the study. CPVdV wrote the empirical section of the manuscript and conducted the statistical analyses. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 1 March 2019; Revised: 20 August 2019; Accepted: 30 November 2019; Published: 31 August 2020.

References

Abbasi T & Fani AA 2006. The relationship between self-awareness and understanding, interpersonal skills and knowledge of career management and environmental management in education [Special issue]. Human Sciences Modares, 1(1):101-120. [ Links ]

Abd. Rahman MF 2000. Perception of industry towards competencies of German-Malaysian institute graduates in relation to their qualification for highly skilled technician. Master's thesis. Johor, Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. [ Links ]

Barnett BG, Shoho AR & Okilwa NSA 2017. Assistant principals' perceptions of meaningful mentoring and professional development opportunities. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 6(4):285-301. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-02-2017-0013 [ Links ]

Cook CR, Gresham FM, Kern L, Barreras RB, Thornton S & Crews SD 2008. Social skills training for secondary students with emotional and/or behavioral disorders: A review and analysis of the metaanalytic literature. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16(3):131-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426608314541 [ Links ]

Cranston N, Tromans C & Reugebrink M 2004. Forgotten leaders: What do we know about the deputy principalship in secondary schools? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(3):225-242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120410001694531 [ Links ]

Daresh JC 2006. Beginning the principalship: A practical guide for school leaders (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Daresh JC & Alexander L 2016. Beginning the principalship: A practical guide for new school leaders (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Daresh JC & Arrowsmith T 2003. A practical guide for new school leaders. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Daresh JC & Playko MA 1992. Induction programs: Meeting the needs of beginning administrators. NASSP Bulletin, 76(546):81-83. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F019263659207654614 [ Links ]

Daresh JC & Playko MA 1994. Aspiring and practising principals' perceptions of critical skills for beginning leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 32(3):35-45. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578239410063102 [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2016. Personnel administrative measures (PAM). Government Gazette, 608(39684):1-216, February 12. Available at http://www.privateschool.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/PAM.pdf. Accessed 6 April 2020. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2017. Strategy to improve school management and governance in schools. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Principals/STRATEGY%20TO%20IMPROVE%20SCHOOL%20MANAGEMENT%20AND%20GOVERNANCE%20IN%20SCHOOLS.pdf?ver=2018-06-27-103843-220. Accessed 8 March 2020. [ Links ]

Dodson RL 2015. What makes them the best? An analysis of the relationship between state education quality and principal preparation practices. International Journal of Educational Policy & Leadership, 10(7):1-21. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1138292.pdf. Accessed 23 February 2020. [ Links ]

Finlay L 2008. Reflecting on 'reflective practice' (Practice-based Professional Learning Centre Discussion Paper 52). Milton Keynes, England: The Open University. Available at http://ncsce.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Finlay-2008-Reflecting-on-reflective-practice-PBPL-paper-52.pdf. Accessed 8 March 2020. [ Links ]

Goleman D 2004. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 82(1):82-91. [ Links ]

Greene A 2017. The role of self-awareness and reflection in social care practice. Journal of Social Care, 1(1):Article 3, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7614X [ Links ]

Harris A, Muijs D & Crawford M 2003. Deputy and assistant head: Building leadership potential. Nottingham, England: National College for School Leadership. Available at https://www.rtuni.org/uploads/docs/Deputy%20and%20Assistant%20Heads.pdf. Accessed 21 March 2020. [ Links ]

Hatami F, Ghahremani L, Kaveh MH & Keshavarzi S 2016. The effect of self-awareness training and painting on self-efficacy of adolescents. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology, 4(2):89-96. https://doi.org/10.15412/J.JPCP.06040203 [ Links ]

Hausman C, Nebeker A, McCreary J & Donaldson G Jr 2002. The worklife of the assistant principal. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(2):136-157. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210421105 [ Links ]

Khumalo JB, Van der Westhuizen P, Van Vuuren H & Van der Vyver CP 2017. The Professional Development Needs Analysis Questionnaire for Deputy Principals. Africa Education Review, 14(2):192-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1294972 [ Links ]

Legotlo MW 1994. An induction programme for newly-appointed school principals in Bophuthatswana. PhD thesis. Potchefstroom, Suid-Afrika: Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys. Beskikbaar te https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/8992. Geraadpleeg 2 Februarie 2020. [ Links ]

Lile S 2008. Defining the role of the assistant principal. National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 55(5):1-11. [ Links ]

Little SG, Swangler J & Akin-Little A 2017. Defining social skills. In JL Matson (ed). Handbook of social behavior and skills in children. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64592-6 [ Links ]

Mailula MJ 2006. A management programme to assist deputy principals in dealing with change. PhD thesis. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: North-West University. Available at https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/2468. Accessed 16 February 2020. [ Links ]

McDaniel L 2017. Andragogical practices of school principals in developing the leadership capacities of assistant principals. PhD dissertation. Macon, GA: Mercer University. [ Links ]

Mohammadiary A, Sarabi SD, Shirazi M, Lachinani F, Roustaei A, Abbasi Z & Ghasemzadeh A 2012. The effect of training self-awareness and anger management on aggression level in Iranian middle school students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46:987-991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.235 [ Links ]

Nasir MD, Ali DF, Noordin MKB & Nordin MSB 2011. Technical skills and non-technical skills: Predefiniton concept. In Proceedings of the IETEC'11 Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ahmad_Nabil_Md_Nasir/publication/259782791_Technical_skills_and_non-technical_skills_predefinition_concept/links/0c96053843a6721934000000.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2020. [ Links ]

National Planning Commission, Republic of South Africa 2012. National Development Plan 2030: Our future-make it work. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-workr.pdf. Accessed 6 April 2020. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuizen L & Brooks JS 2013. The assistant principal's duties, training, and challenges: From colour-blind to a critical race perspective. In JS Brooks & NW Arnold (eds). Antiracist school leadership: Toward equity in education for America's students. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Oliver R 2005. Assistant principal professional growth and development: A matter that cannot be left to chance. Educational Leadership and Administration, 17:89-100. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ795084.pdf. Accessed 10 February 2020. [ Links ]

Owen-Fitzgerald V 2010. Effective components of professional development for assistant principals. DEd thesis. Fullerton, CA: California State University. [ Links ]

Petrides L, Jimes C & Karaglani A 2014. Assistant principal leadership development: A narrative capture study. Journal of Educational Administration, 52(2):173-192. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2012-0017 [ Links ]

Potgieter PC 1990. Die inskakeling van nuutaangestelde adjunk-hoofde van sekondêre skole. MEd skripsie. Potchefstroom, Suid-Afrika: Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys. Beskikbaar te http://dspace.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/8944/Potgieter_PC.pdf?sequence=1. Geraadpleeg 2 Februarie 2020. [ Links ]

Safarihalavi A 2012. I actually can't. Journal of Philosophy, 40(1):84-101. [ Links ]

Urdang E 2010. Awareness of self-a critical tool. Social Work Education, 29(5):523-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903164950 [ Links ]

Weller LD & Weller SJ 2002. The assistant principal: Essentials for effective school leadership. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Yip KS 2006. Self-reflection in reflective practice: A note of caution. The British Journal of Social Work, 36(5):777-788. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch323 [ Links ]