Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 supl.1 Pretoria abr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40ns1a1899

ARTICLES

School counsellors' perceptions of working with gifted students

Deniz OzcanI; Huseyin UzunboyluII

IDepartment of Special Education, Faculty of Education, Ondokuz Mayis University, Samsun, Turkey. deniz.ozcan@omu.edu.tr

IINear East University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Special Education Program, Nicosia, North Cyprus, Mersin 10, Turkey, and Higher Education Planning, Supervision, Accreditation and Coordination Board, Nicosia, North Cyprus, Mersin 10, Turkey

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to determine the perceptions of school counsellors who work with gifted students in the school environment. A qualitative research design was used in this study. The participants were 52 school counsellors who work in primary schools of private colleges accepting gifted students in Turkey. A semi-structured interview schedule was used as a data collection tool. Data analysis was conducted through content analysis. Results show that school counsellors need training on how to provide efficient counselling and guidance to address the personal, academic and social challenges experienced by gifted students.

Keywords: academic characteristics; giftedness; personality characteristics; qualitative research; social relations

Introduction

The world has experienced many important changes in recent years, such as education innovations, technological developments, increased environmental awareness, human health innovations, economic growth and countless new expectations from the field of information technologies (Bhattarai, 2015; Guler, 2016; Iyer, 2016; Voloshina, Demicheva, Reprintsev, Stebunova & Yakovleva, 2019). While technological developments require a very careful process (Cetinkaya, 2019), one of the most important developments in the field of education involved focusing more closely on the education of gifted children (Sahmurov, Aylak, Bedirhanbeyoglu & Gulen, 2017). The teaching of gifted students is seen as a sub-branch of special education, and the theoretical and research aspects are examined from a special education perspective (Akmese & Kayhan, 2016).

Giftedness is asynchronous development where advanced cognitive abilities and heightened intensity combine to create inner experiences and awareness that are qualitatively different from the norm. This asynchronicity increases with higher intellectual capacity (Webb, Gore, Amend & DeVries, 2007). The uniqueness of the gifted renders them particularly vulnerable and requires modifications to mainstream parenting, teaching, and counselling methods for them to develop optimally (Andrew, 1994). Gifted students differ from their peers in terms of the psychological counselling and guidance services that they need. In addition to their varying cognitive capacities, gifted students exhibit different affective development (e.g., sensitivity, intensity, perceptiveness, excitability, divergent thinking, precocious talent development and advanced moral development). Their needs, concerns, and how they experience development may be quite different (National Association for Gifted Children [NAGC], n.d.). Rapid information processing in itself may contribute to possible intense emotional responses to environmental stimuli. The characteristics just mentioned may even contribute to difficulties in carrying out developmental tasks. In general, it is important that parents, educators, counsellors, psychologists and psychiatrists are informed about the affective development of gifted children and adolescents, and apply that knowledge to their relationships with this population (NAGC, n.d.). Although gifted students generally develop healthy social relationships, they can experience difficulties as a result of their leadership characteristics. Guidance counsellors have a great responsibility to help these students express themselves, attain a sense of belonging and overcome any difficulties they may experience in social relationships (Colangelo, 2002; Moon, 2002; Robinson & Noble, 1991; Sak, 2014a).

Gifted students may be regarded as socially and emotionally similar to their non-gifted peers, with similar guidance and counselling needs (Colangelo, 1997; Neihart, Reis, Robinson & Moon, 2002; Silverman, 1993). However, current literature indicates the necessity of special assistance for gifted students in various areas and under several conditions, which include emotional intensity and increased sensitivity (Lovecky, 1993; Mendaglio, 2002), perfectionism (Schuler, 2002), depression (Neihart et al., 2002; Silverman, 1993), feeling different from others (Coleman & Cross, 2001), social isolation (Silverman, 1993), social skills deficits/peer-relationship problems (Moon, Kelly & Feldhusen, 1997; Webb, Meckstroth & Tolan, 1989), and stress management issues (Moon, 2002; Webb et al., 1989). In addition to these needs, Cross (2004) states that the social and emotional needs of gifted students are not static, but are greatly influenced by the environment and culture in which they live. Some of these difficulties may be exacerbated in students with dual or multiple exceptionalities who may lack effective coping skills or who may already be cognitively or affectively overwhelmed at school (Silverman, 1993). Metin and Aral (2020) argue that gifted students with advanced academic and intellectual abilities differ from average children. Their ability to learn faster and think more quickly and deeply than average students, while requiring less repetition or practice to master assigned material, provides for greater educational challenges in their studies (Coleman & Cross, 2001; Sak, 2014a; Silverman, 1993; VanTassel-Baska, 1998). However, if no challenges are academically presented, these students can become bored and exhibit disruptive behaviour.

A lack of goals, motivation or direction, and failure to develop self-regulatory strategies can affect the academic performance of gifted students for various reasons (Attar, 2019; Siegle & McCoach, 2002). They may feel pressured to meet the expectations of their parents or teachers, and many are afraid of academic failure and frustration (Ataman, 2014; Sak, 2014a; Schuler, 2002; Silver-man, 1993). Gifted students may also need special assistance with university and career planning (Colangelo, 2002; Silverman, 1993). Moreover, it can be difficult for gifted students to narrow their career choices because they can do so many things extremely well (Greene, 2002; Silverman, 1993), thus necessitating guidance during this decision-making period.

Specialised guidance and counselling services for gifted students to address their unique personal, social and academic characteristics are needed to gain maximum educational achievement (Col-angelo, 1997, 2002; Kerr, 1991; Moon, 2004; Peterson, 2002; Reis & Renzulli, 2004; Silverman, 1993; Tsikati, 2018; VanTassel-Baska, 1990).

Many studies in the existing literature have focused on social and emotional development, and more specifically on how the counselling needs of gifted children should be addressed by parents, educators and clinical practitioners (Moon, 2004). According to Lovecky (1993) and Peterson (2002), the common myth among educators, counsellors, school psychologists, and even mental health professionals is that gifted students do not need any additional or specialised guidance to address their advanced abilities.

Cross (2004) and Silverman (1993) claim that effective psychological and counselling programmes for gifted students are valuable for their positive effects on psychological and social development, and for their support and guidance of these students in a public education system that is not inherently designed to improve or maximise their success. School counsellors provide specialised support and guidance to gifted students in academic, vocational, social and emotional domains (Peterson, 2008). However, many educators and parents have realised that these children have complex social and emotional needs due to their extraordinary capabilities.

No formal public institutions for gifted students exist in Turkey other than the Anatolian Fine Arts High Schools (secondary level) and Science and Art Centres, which are both contingent on support from the Ministry of National Education. As for private institutions, there are colleges using differentiated education programmes for educating gifted children. They select those students through exams and offer them scholarships for their education. It is estimated that there are nearly 700,000 gifted students in Turkey, despite the restricted number of institutions. Consequently, gifted students are educated in regular classrooms, which creates problems or challenges for both the teacher and their peers (Keser & Erdem, 2019; Milli Egitim Bakanligi [MEB], 2013).

Research has indicated that gifted students experience discomfort when participating in group work, and that they prefer to work alone because they are afraid of being misunderstood (Mendaglio & Peterson, 2007). On the other hand, teachers may observe behaviour or emotional problems exhibited by gifted children in the classroom, which could possibly be due to the fact that they have a more sensitive nature compared to other children and may perceive the class work as being too easy. Hence, they may actually withdraw from classroom activities (Manning, 2006). In this situation, the gifted children need the support of specialised school counsellors to overcome these challenges. School counsellors in Turkey are trained in general education faculties at universities, where the gifted education course occupies only one part of the special education course. It does not exist in teacher-training programmes and, in addition, hardly any in-service training programmes on how to work with gifted students are available for volunteer counsellors. Therefore, it is important to identify the problems that school counsellors experience in supporting gifted students in the school environment, and to provide solutions.

Aim of the Research

The aim of the study was to determine the perceptions of school counsellors working with gifted students in the school environment. To reach this aim, the study sought to answer the following questions.

1) What are the difficulties that school counsellors experience as a result of gifted students' personality characteristics?

2) What are the difficulties that school counsellors experience as a result of gifted students' academic characteristics?

3) What are the difficulties that school counsellors experience as a result of gifted students' issues with social relations?

4) What are the views of school counsellors regarding their professional competencies for guiding gifted students?

Methodology

The qualitative method was used in this study. This method is used to answer questions about experiences, meaning and perspective - most often from the standpoint of the participant. The data acquired is usually not amenable to counting or measuring. Using the qualitative research method means including small-group discussions for investigating beliefs, attitudes, and concepts of normative behaviour; semi-structured interviews to seek views on a focused topic or with key informants, for background information or an institutional perspective; in-depth interviews to understand a condition, experience or event from a personal perspective; and analysis of texts and documents such as government reports, media articles, websites or diaries to learn about distributed or private knowledge (Hammarberg, Kirkman & De Lacey, 2016; Rader, 2013). In this study semi-structured interviews were used to seek the participants' views on gifted students.

Participants

The participants in this study included 52 school counsellors who work in primary schools at 18 private colleges that accept gifted students in Istanbul, Turkey. As working with gifted students was a requirement for participation, purposive sampling was used to select school counsellors at schools where gifted students had been enroled. Purposive sampling (also known as judgement, selective, or subjective sampling) is a sampling technique in which the researcher relies on his or her own judgement when choosing the population of the study (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2012). Participation in this study was voluntary.

Data-Collection Tool and Data-Collection Process A semi-structured interview schedule was used as a data collection tool. This is the most common format of data collection in qualitative research. According to Oakley (1998), a qualitative interview is a type of framework in which the practices and standards are not only recorded, but also achieved, challenged and reinforced.

Interviews are frequently used in qualitative studies to investigate opinions, emotions or experiences in depth. This technique requires the researcher to structure an interview that consists of open-ended questions and, depending on the outcome of the interview, the researcher can incorporate follow-up questions to enhance their understanding of the data (Turnuklu, 2000; Yildirim & §ims.ek, 2008).

Related literature was examined thoroughly, and issues mentioned in the reviewed literature formed the basis of the questions in the semi-structured interview used to collect data in this study. The semi-structured interview schedule consisted of three questions: "What kinds of problems do you experience with gifted students while guiding them?"; "Which factors make your guiding process difficult?"; and "What do you think about your professional competency to guide gifted students?" To enable clear and efficient interaction with the school counsellors, questions were designed to attain open and detailed answers from participants. After the first draft of the semi-structured interview form had been composed, eight guidance counsellors, four special education counsellors, three assessment and evaluation specialists and three teachers were consulted for their opinions. A pilot study with five participants was conducted through phone conversations to test the content validity and reliability of the instrument.

School counsellors were contacted by phone and appointments were arranged to conduct the semi-structured interviews. The researcher conducted the interviews face to face over a period of four months. Each interview of 8 to 12 minutes was audiorecorded.

Data Analysis

The content analysis technique was used to analyse the collected data. Content analysis is defined as summarising a text with specific encodings and smaller content categories (Büyüköztürk, Kiliç Cakmak, Akgün, Karadeniz & Demirel, 2008). According to Tavçancil and Aslan (2001), content analysis is defined as a scientific approach that investigates the social reality by objectively and systematically classifying the message, meaning and linguistic information (verbal and written), as well as other materials. In our study a specific type of content analysis was used, namely categorical analysis. In general, this type of analysis refers to the division of a given message into units and then grouping these units into categories according to certain criteria (Bilgin, 2006).

Often, transcribed interview texts constitute a common starting point for qualitative content analysis. The objective in such analysis is to systematically transform a large amount of text into a highly organised and concise summary of key results. Analysis of the raw data from verbatim transcribed interviews to form categories or themes is a process of further abstraction of data at each step of the analysis - from the manifest and literal content to latent meanings. Researchers play an active role during the instrument development, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the result processes. Three different experts in the field were asked to comment on the reliability and appropriateness of the codes and themes. Miles and Huber-man's (1994) agreement and disagreement formula was considered to determine the reliability and appropriateness for use of each code. Reliability value was calculated as 90% and as such themes were created. The findings are explained in the form of tables, and direct quotations are given to confirm the reliability of the themes.

Results

This section reports on the findings of the study regarding the difficulties that school counsellors experienced when working with gifted students.

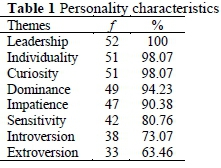

The Difficulties that School Counsellors Experienced as a Result of the Personality Characteristics of Gifted Students were Categorised under Eight Themes

As shown in Table 1, the difficulties that school counsellors experienced based on the personality traits of gifted students seemed to be due to the students' leadership qualities f = 52), individuality f= 51), curiosity f = 51), dominance f= 49), impatience f = 47), sensitivity to events f = 42), periodic introversion f = 38), and extreme extroversion characteristics (f = 33). As seen in the table, the personality traits of gifted students are such that they make it difficult for school counsellors to assist them. This finding is evidenced in the following striking responses:

Behaviours of gifted students are different from their peers. They always aim to be at the 'top of the world.' They always need their own space and the environment that can suit their superiority. Because their self-esteem is so high, they tend not to accept classroom teachers as authority. They are in pursuit of different expectations in the classroom environment; when these possibilities are not provided, they tend to reject becoming part of the classroom environment. (Participant 24) Their perfectionist nature makes them feel frazzled. Even if they are superior in some aspects, we are having difficulties providing opportunities for developmental satisfaction that their age requires. Even if they have a strong sense of providing personal and social services in the best possible way, we do not always achieve the desired success. (Participant 11)

I can observe different personality traits with my students who are recognised as gifted. Some students are seen to be directing people around them without being aware of what they are doing. In addition, they do not accept any instruction and insist on doing what they wish to do. (Participant 32) One of the most outstanding problems which I come across is that they can shut themselves down from healthy communication and isolate themselves in the classroom. They seem not to share their knowledge and their opinions, and they do not want to engage in team work. They prefer to study individually to solve their own problems. (Participant 51)

They get angry with the students' questions on the topics studied in classroom. The class time is long for them and they tend to get bored, resulting in bad classroom harmony (Participant 3). We have encountered various aspects associated with personality traits of gifted students. They can be extroverted and social. They want to behave according to their own rules, which can lead to violations of class rules, as well as class mismatches. While students being introverts do not have any difficulties with class rules, they have serious problems in social relations, and they are always faced with self-abstraction. (Participant 43) Gifted students invariably elicit responses from their peers and their teachers because they ask so many questions and criticise everything. I have difficulties in solving this problem since the logic and the method conducted by me does not satisfy these students. This entails that the school counsellor cannot provide sufficient guidance to prevent this situation. (Participant 14)

The Difficulties that School Counsellors

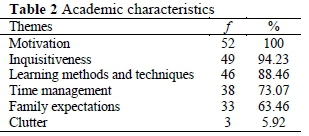

Experienced as a Result of the Academic Characteristics of Gifted Students were Categorised under Six Themes

As shown in Table 2, the difficulties that school counsellors experienced with the academic characteristics of gifted students were mostly motivation (f = 52), inquisitive characteristics (f = 49), learning methods and techniques f = 46), time management f = 38), family expectations f = 33) and scattered or cluttered work (f = 3). School counsellors generally struggled to guide gifted students when faced with their low motivation and their need for different learning methods and techniques in classrooms. They also struggled to deal with their endless inquisitiveness.

These difficulties are evidenced in the following responses:

While many gifted students are expected to have high academic performance in their community, I cannot observe the majority of these children academically in the same paradigm. While doing individual work, they cannot stay focused on one activity for a long time and they get overstressed by classwork and do negative interventions in their peers' work. Similarly, their use of the notebooks and books continues to be cluttered and irregular. (Participant 2)

I can observe that gifted students have a strong affinity with numbers. They can construct their knowledge and create new things individually using their own learning methods and techniques. Hence, they are tightly pressed into the classroom [sic] and show different negative reactions. With decreased motivation, they exhibit behavioural disorders in the classroom such as playing with pens and biting their pencils to attract teachers' attention. (Participant 17)

Gifted students are subjected to the same academic and performance examinations as other students, resulting in evaluation errors. These high-potential students are either getting clear high scores or are scoring low on meaningless levels due to low motivation. Another difficulty related to the academic performance of these gifted students is the expectations from their families, teachers, school administration and school counsellors. (Participant 39)

The Difficulties that School Counsellors

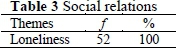

Experienced as a Result of Gifted Students' Issues in Social Relations were Categorised under a Single Theme

As shown in Table 3, the difficulties that school counsellors experienced in terms of the social relations of gifted students are entirely related to loneliness f = 52, 100%). All of the school counsellors agreed that this problem was caused by the leadership and sensitivity characteristics of gifted students.

After a short time in a social setting, they get acquainted with the people around them, but this acquaintance happens spontaneously. Gifted students always want to be popular among their friends, to manage the game and play it. Such an attitude is usually criticised by other students causing them to withdraw and to stay alone. In these cases, I experience difficulties in supporting these students in the socialisation process. (Participant 13)

The Difficulties that School Counsellors

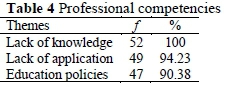

Experienced in Respect of their Professional Competencies for Guiding Gifted Students Emerged as Three Themes

As shown in Table 4, three themes were derived from the views of school counsellors regarding the level of their own professional competence for guiding gifted students. They are focused on a lack of training f = 52) at bachelor's degree level, inadequacies due to implementation deficiencies (f = 49), and gaps in education policy (f = 47). School counsellors indicated that they neither had enough knowledge to guide gifted students nor enough work experience with them. Moreover, because of education policies, they did not know exactly what their main responsibilities were, and they were uncertain about their working hours or working areas. As voiced by one of the study participants, they were in fact handicapped regarding the best way to serve these students and families.

The reasons behind the above inadequacies were expressed by the school counsellors as follows:

I think it would be beneficial to have elective and compulsory courses related to children having development disorders and in need of special education in the psychological counselling and guidance programmes in undergraduate education. Knowledge related to giftedness is crucial for a successful guidance of these students. Unfortunately, the university did not equip us with the necessary tools to guide the gifted children. (Participant 24)

I can say that the schools have problems in diagnosing gifted children, especially when they inform the schools about identifying specific areas of gift-edness. Problems arising from differences between areas can be reflected in children's thoughts, and emotional and behavioural situations. For this reason, school counsellors will keep suffering from these issues until they receive adequate training and support from outside. We also have difficulties in meeting the expectations of parents about the academic and social development of these children. (Participant 50)

Three different steps need to be functional for gifted students to benefit from guidance services effectively. The first one is to recognise the gifted students; the second one is to avail them of appropriate training; and the third step is to direct them to higher education opportunities. In these three steps, we, the school counsellors, should play an active role. However, we do not consider ourselves professional enough to manage these steps because the education policy of the state is not clear enough about gifted students. We do not even know our main responsibilities, working hours, or working areas. We are, in fact, handicapped regarding the best way to serve these students and families. (Par ticipant 47)

Discussion and Conclusion

A recent American study of college courses on school guidance counselling found little evidence of any training in the characteristics, social and emotional development, or counselling needs of high-ability (gifted) students (Peterson, 2002). The prevailing attitude there seems to be that bright students do not really need guidance counsellors much, because they are smart enough to figure things out for themselves. Unfortunately, this attitude seems to be quite pervasive. Children with an extended vocabulary or great curiosity about how things work may show early signs of giftedness. Other characteristics are not so obvious, making it difficult to identify gifted children in many settings, even at school. It is useful for guidance counsellors to be familiar with and able to recognise traits of giftedness that can be used to help the classroom teacher. Based on the results of our research, it can be said that school counsellors have difficulty in guiding gifted children toward academic success because of the latter's personal characteristics, which include leadership spirit, impatience, curiosity, periodic introversion, extreme extroversion, dominance, individualism, and extreme sensitivity to events. Counsellors struggle to solve these behaviour problems because the logic and methods they use do not satisfy these students' needs. They will not be able to achieve much as long as these extreme character traits are not under their control, and they currently lack the training, theoretical knowledge and skills to deal effectively with these personal characteristics of gifted students. Many counselling issues arise from the incompatibility of the unique features of gifted individuals with their environment (Maree, 2019a; Robinson, 2002). According to Webb, Amend, Webb, Goerss, Beljan and Olenchak (2005), the common themes for which gifted children of school age need counselling include fear of failure, stubbornness, overreacting, difficulty with peer relations, intense sibling rivalry, low self-esteem, perfectionism, and depression. However, the counsellor can experience challenges in conveying knowledge to these students about their abilities. Counsellors should have a strong theoretical base and knowledge of the characteristics of gifted children to provide them with effective counselling services.

Another difficulty that school counsellors experience relates to the academic characteristics of gifted students. These include both low and high levels of motivation, inquisitiveness, time management, uncommon learning methods and techniques, scattered and cluttered study, as well as the expectations of their families. They learn at a faster pace, think or process more deeply, and require less repetition or practice to master assigned material, thus warranting greater educational challenges in their coursework (Coleman & Cross, 2001; Maree, 2019b; Sak, 2014b; Silverman, 1993). More specifically, these students have learning methods and techniques that differ from those used by other students in the class environment and that often result in boredom and demotivation of gifted students during regular classroom studies. A one-size-fits-all application in the regular classroom is not suitable for this kind of student who has scattered and cluttered studying preferences. The expectations of gifted students' families for the students' self-development and academic success are extremely high. However, most school counsellors lack the knowledge and practice to guide and empower students and to fulfil the expectations of their families. The academic achievements of gifted students may not always be realised to the full extent of their abilities, as being gifted may not be the only criterion for academic success. Achievement requires motivation and effective work practices in addition to talent. Gifted students need to

be able to fulfil their potential and must be guided in their academic endeavours. They need counselling services to help them with time management, motivation, efficient study methods and techniques. It is also necessary for these students to enrich their learning experiences with effective classroom activities and diversified instructional programmes in which they feel comfortable and where they can express their opinions freely. School counsellors play an important role in supporting those students who very often face problematic issues and challenges associated with academic life. Counselling services can be effective in supporting students across a wide range of issues (Pattison & Harris, 2006).

In addition to difficulties based on gifted students' personal and academic characteristics, the social issues they experience can create difficulties for school counsellors who struggle to help them to avoid feeling lonely. All of the school counsellors in our study concurred that this problem was caused by the students' leadership and sensitivity characteristics. The more talented the student, the more likely that he/she experiences difficulty in respect of social relations with peers. Hollingworth (1926) defined an IQ range of 125-155 as "socially best intelligence," as the children who scored in this range tended to be more balanced, self-confident and outgoing than peers above the 160 IQ level. Very high IQ leads to particular social development problems that correlate with social isolation (Ataman, 2014; Maree, 2017; Sak, 2014b). However, the social isolation of the children in our study was not the clinical isolation of emotional distress, nor did it result from the fact that the children were gifted. Rather, it was due to the lack of a suitable peer group with which to connect or relate (DeHaan & Havighurst, 1961; Gross, 1993; Janos, 1983; Maree, 2019c; Rosenberg, 1959).

The most important and general conclusion that we could draw was that school counsellors lacked knowledge about the characteristics of gifted students, which was why they struggled to guide and counsel the gifted students in terms of personal and academic characteristics and social relations. The school counsellors reported a lack of training at the bachelor degree level at university, gaps in education policy on gifted education, and a lack of expertise with these students. As discussed previously, knowledge issues related to giftedness are crucial in guiding gifted students. However, it has been noted that the knowledge and training provided by universities are not enough to effectively train counsellors on how to work with gifted students. School counsellors therefore graduate without having a strong theoretical basis or knowledge of the characteristics of gifted children. Furthermore, the education policies are not clear about the role of school counsellors or the education of gifted students.

Most of the school counsellors in our study were or had been employed as teachers before becoming counsellors. Despite the obligations of and demands on senior psychologists and guidance counsellors regarding proper in-service training for school counsellors, no training is typically provided (Campbell & Wackwitz, 2002; Maree, 2019b). Universities need to train more school psychologists and counsellors to engage in gifted education research. Meanwhile, professional associations need to encourage this research and grant scholarships to provide avenues for the dissemination of best practices and to highlight and promote services - both at academic and at state/governmental policy levels (Campbell & Colmar, 2014; Maree, 2016, 2020).

To conclude, gifted students tend to differ from their peers regarding their psychological counselling and guidance service needs. In addition to their advanced cognitive development, gifted children can exhibit differing emotional development, depending on their individual characteristics. This varying development potentially elicits a variety of psychological issues. Gifted students form a special group that requires special counselling by well-educated and trained professionals who are mindful of their students' tendencies toward abnormal behaviour and who are acutely conscious of their feelings. After all, gifted students are regarded as the architects of the future and school counsellors are expected to assess and respond to their needs. Therefore in-service training programmes should be arranged for school counsellors to focus on the personal, academic and social characteristics of gifted students, and to examine what their families expect from school counsellors.

Authors' Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to each stage of the research.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

ii. DATES: Received: 6 September 2019; Revised: 2 October 2019; Accepted: 22 January 2020; Published: 30 April 2020.

References

Akmese PP & Kayhan N 2016. An examination of the special education teacher training programs in Turkey and European Union member countries in terms of language development and communication education. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 11(4):185-194. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v11i4.742 [ Links ]

Andrew SM 1994. Exceptional children require an exceptional approach: Issues in counselling gifted children (Vol. 4). Counselling and Guidance Newsletter, Summer. [ Links ]

Ataman A 2014. Ustun zekaltlar ve ustunyetenekliler konusunda bilinmesi gerekenler [What to know about gifted and talented]. Ankara, Turkey: Vize Yayincilik. [ Links ]

Attar S 2019. A design of gifted personality traits scale. International Journal of Learning and Teaching, 11(2):049-059. https://doi.org/10.18844/ijlt.v11i2.929 [ Links ]

Bhattarai B 2015. Socio-economic impact of hydropower projects in dzongu region of North Sikkim. Global Journal of Sociology, 5(1): 14-27. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjs.v5i1.79 [ Links ]

Bilgin N 2006. Sosyal bilimlerde içerik analizi: Teknikler ve örnek çaltsmalar [Content analysis in social sciences: Techniques and case studies]. Ankara, Turkey: Siyasal Kitabevi. [ Links ]

Büyüköztürk S, Kiliç Cakmak E, Akgün OE, Karadeniz S & Demirel F 2008. Bilimsel arasttrma yöntemleri[Scientific research methods]. Ankara, Turkey: Pegem A Yayincilik. [ Links ]

Campbell M & Colmar S 2014. Current status and future trends of school counseling in Australia. Journal of Asia Pacific Counselling, 4(2):181 -197. https://doi.org/10.18401/2014.4.2.9 [ Links ]

Campbell M & Wackwitz H 2002. Supervision in an organization where counsellors are a minority profession. In M McMahon & W Patton (eds). Supervision in the helping professions: A practical guide. Sydney, Australia: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Cetinkaya L 2019. The usage of social network services in school management and their effects. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 11(1):116-127. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v11i1.4014 [ Links ]

Colangelo N 1997. Counseling gifted students: Issues and practices. In N Colangelo & GA Davis (eds). Handbook of gifted education (2nd ed). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Colangelo N 2002. Counselling gifted and talented students. The National Research Center on the Gifted Newsletter, Fall. Available at https://nrcgt.uconn.edu/newsletters/fall022/. Accessed 21 April 2020. [ Links ]

Coleman LJ & Cross TL 2001. Being gifted in school: An introduction to development, guidance, and teaching. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Cross TL 2004. On the social and emotional lives of gifted children: Issues and factors in their psychological development (2nd ed). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

DeHaan RF & Havighurst RJ 1961. Educating gifted children. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Greene MJ 2002. Career counseling for gifted and talented students. In M Neihart, SM Reis, NM Robinson & SM Moon (eds). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Gross MUM 1993. Exceptionally gifted children. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Guler A 2016. Effectiveness of expectation channel of monetary transmission mechanism in inflation targeting system: An empirical study for Turkey. Global Journal of Business, Economics and Management: Current Issues, 6(2):222-231. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjbem.v6i2.1394 [ Links ]

Hammarberg K, Kirkman M & De Lacey S 2016. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Human Reproduction, 31(3):498-501. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334 [ Links ]

Hollingworth LS 1926. Gifted children: Their nature and nurture. New York, NY: Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1037/10599-000 [ Links ]

Iyer VG 2016. Social impact assessment process for an efficient socio-economic transformation towards poverty alleviation and sustainable development. Global Journal on Advances in Pure & Applied Sciences, 7:150-169. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjpaas.v0i7.3175 [ Links ]

Janos PM 1983. The psychological vulnerabilities of children of very superior intellectual ability. PhD dissertation. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University. Available at https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=osu1487239392029118&disposition=inline. Accessed 15 March 2020. [ Links ]

Kerr B 1991. A handbook for counseling the gifted and talented. Alexandria, VA: American Association for Counseling and Development. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED334473.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2020. [ Links ]

Keser SC & Erdem P 2019. The effectiveness of plastic arts education weighted creative drama in the education of gifted/talented children. Contemporary Educational Researches Journal, 9(1):032-037. https://doi.org/10.18844/cerj.v9i1.3856 [ Links ]

Lovecky DV 1993. The quest for meaning: Counseling issues with gifted children and adolescents. In LK Silverman (ed). Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver, CO: Love Publishing. [ Links ]

Manning S 2006. Recognizing gifted students: A practical guide for teachers. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 42(2):64-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2006.10516435 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2016. Career construction counseling with a mid-career Black man [Special issue]. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(1):20-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12038. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2017. Gifted education in Africa. In SI Pfeiffer (ed). APA handbook of giftedness and talent. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2019a. Career construction counselling aimed at enhancing the narratability and career resilience of a young girl with a poor sense of self-worth. Early Child Development and Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1622536 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2019b. Group career construction counseling: A mixed-methods intervention study with high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 67(1):47-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12162 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2019c. Self- and career construction counseling for a gifted young woman in search of meaning and purpose. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19:217237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-018-9377-2 [ Links ]

Maree JG 2020. Innovative career construction counselling for a creative adolescent. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 48(1):98-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1504202 [ Links ]

Mendaglio S 2002. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: Implications for counseling. Journal of Advanced Academics, 14(2):72-82. https://doi.org/10.4219%2Fjsge-2003-421 [ Links ]

Mendaglio S & Peterson JS (eds.) 2007. Models of counseling gifted children, adolescents, and young adults. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Metin S & Aral N 2020. The drawing development characteristics of gifted and children of normal development. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 15(1):73-84. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v15i1.4498 [ Links ]

Miles MB & Huberman AM 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Milli Egitim Bakanligi 2013. Üstün tetenekli bireyler strateji ve uygulama plant 2013 - 2017 [Strategy and implementation plan for gifted individuals 2013 - 2017]. Ankara, Turkey: Author. Available at https://www.tubitak.gov.tr/sites/default/files/10_ek-1_ustunyetenekliler.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2020. [ Links ]

Moon SM 2002. Counseling needs and strategies. In M Neihart, SM Reis, NM Robinson & SM Moon (eds). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Moon SM (ed.) 2004. Social/emotional issues, underachievement, and counseling of gifted and talented students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Moon SM, Kelly KR & Feldhusen JF 1997. Specialized counseling services for gifted youth and their families: A needs assessment. Gifted Child Quarterly, 41(1):16-25. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F001698629704100103 [ Links ]

National Association for Gifted Children n.d. What is giftedness? Available at http://www.nagc.org/resources-publications/resources/definitions-giftedness?id=574. Accessed 15 September 2019. [ Links ]

Neihart M, Reis SM, Robinson NM & Moon SM (eds.) 2002. The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Oakley A 1998. Gender, methodology and people's ways of knowing: Some problems with feminism and the paradigm debate in social science. Sociology, 32(4):707-731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038598032004005 [ Links ]

Pattison S & Harris B 2006. Counselling children and young people: A review of the evidence for its effectiveness. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 6(4):233-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140601022659 [ Links ]

Peterson JS 2002. An argument for proactive attention to affective concerns of gifted adolescents. Journal of Advanced Academics, 14(2):62-70. https://doi.org/10.4219%2Fjsge-2003-419 [ Links ]

Peterson JS 2008. The essential guide to talking with gifted teens: Ready-to-use discussions about identity, stress, relationships, and more. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing. [ Links ]

Rader DJ 2013. Deterministic operations research: Models and methods in linear optimization. Hoboken, NJ: John Willey & Sons. [ Links ]

Reis SM & Renzulli JS 2004. Current research on the social and emotional development of gifted students: Good news and future possibilities. Psychology in the Schools, 41(1):119-130. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10144 [ Links ]

Robinson NM 2002. Assessing and advocating for gifted students: Perspectives for school and clinical psychologists (RM02166). Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476372.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2020. [ Links ]

Robinson NM & Noble KD 1991. Social-emotional development and adjustment of gifted children. In MC Wang, MC Reynolds & HJ Walberg (eds). Handbook of special education: Research and practice (Vol. 4). Bingley, England: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Rosenberg S 1959. Exposure interval in incidental learning. Psychological Reports, 5(3):675-675. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1959.5.3.675 [ Links ]

Sahmurova A, Aylak U, Bedirhanbeyoglu H & Gulen IO 2017. Examination of the relationship between giftedness and ADHD symptoms during educational processes. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences, 7:52-57. https://doi.org/10.18844/prosoc.v4i3.2631 [ Links ]

Sak U 2014a. Üstun zekalilar: Özellikleri, tanilanmalari, egitimleri [Characteristics, diagnoses and education of gifted children]. Ankara, Turkey: Vize Yayincilik. [ Links ]

Sak U 2014b. Yaraticilik gelisimi ve gelistirilmesi [Creativity development]. Ankara, Turkey: Vize Yayincilik. [ Links ]

Saunders MNK, Lewis P & Thornhill A 2012. Research methods for business students (6th ed). London, England: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Schuler P 2002. Perfectionism in gifted children and adolescents. In M Neihart, SM Reis, NM Robinson & SM Moon (eds). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Siegle D & McCoach DB 2002. Promoting a positive achievement attitude with gifted and talented students. In M Neihart, SM Reis, NM Robinson & SM Moon (eds). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. [ Links ]

Silverman LK (ed.) 1993. Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver, CO: Love Publishing. [ Links ]

Tavsancil E & Aslan AE 2001. Sözel, yazili ve diger materyaller için içerik analizi ve uygulama örnekleri [Content analysis and application examples for verbal, written and other materials]. Istanbul, Turkey: Epsilon Yayincilik. [ Links ]

Tsikati AF 2018. Factors contributing to effective guidance and counselling services at university of Eswatini. Global Journal of Guidance and Counselling in Schools: Current Perspectives, 8(3):139-148. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjgc.v8i3.3716 [ Links ]

Turnuklu A 2000. Egitimbilim arastirmalarinda etkin olarak kullanilabilecek nitel bir ara§tirma teknigi: Görüsme [An effective qualitative research method for educational sciences: Interview]. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Yönetimi [Educational Administration: Theory and Practice], 6(24):543-559. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/108517. Accessed 21 February 2020. [ Links ]

VanTassel-Baska J (ed.) 1990. A practical guide to counseling the gifted in a school setting (2nd ed). Reston, VA: The Council for Exceptional Children. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED321512.pdf. Accessed 28 March 2020. [ Links ]

VanTassel-Baska J 1998. Counselling gifted learners. In J VanTassel-Baska (ed). Excellence in educating gifted and talented learners (3rd ed). Denver, CO: Love Publishing. [ Links ]

Voloshina LN, Demicheva VV, Reprintsev AV, Stebunova KK & Yakovleva TV 2019. Designing an independently installed educational standard for 'teacher education'. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 14(2):294-302. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v14i2.4240 [ Links ]

Webb JT, Amend ER, Webb NE, Goerss J, Beljan P & Olenchak FR 2005. Misdiagnosis and dual diagnoses of gifted children and adults: ADHD, bipolar, OCD, Asperger's, depression, and other disorders. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press. [ Links ]

Webb JT, Gore JL, Amend ER & DeVries AR 2007. A parent's guide to gifted children. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press. [ Links ]

Webb JT, Meckstroth EA & Tolan SS 1989. Guiding the gifted child: A practical source for parents and teachers. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press. [ Links ]

Yildirim A & Simsek H 2008. Sosyal bilimlerde nitel arastirma yöntemleri [Qualitative research methods in social sciences]. Ankara, Turkey: Seçkin Yayinlari. [ Links ]