Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.2 Pretoria May. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n2a1455

ARTICLES

Case study of isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners who experience barriers to learning in an English-medium disadvantaged Western Cape school

Maimona SalieI; Mokgadi MoletsaneI; Robert Kananga MukunaII

IDepartment of Educational Psychology, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

IIDepartment of Psychology of Education, School of Education Studies, University of the Free State, QwaQwa, South Africa mukunakr@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In the study reported on here, we focused on the use of English as language of learning and teaching (LoLT) for isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners in a historically disadvantaged school in the Western Cape, South Africa. It was a qualitative case study within an interpretive research paradigm. We used focus groups and interviews for data collection and conducted thematic analysis for the qualitative findings. The participants were 12 Foundation Phase learners (6 females and 6 males aged 7-9 years), 8 female Foundation Phase teachers (aged 29-56 years) and 12 parents/caregivers (aged 29-57 years). The results from this study show that isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners growing up in historically disadvantaged areas and attending disadvantaged schools experience several barriers to learning. The barriers to learning investigated included exposure to isiXhosa as primary language, psychological-social barriers, English as language barrier to teaching and learning and a lack of parental involvement and support.

Keywords: barriers to learning; English as language of learning and teaching; Foundation Phase; historically disadvantaged schools; inclusive education; isiXhosa-speaking learners

Introduction

As a result of political, socio-economic and educational transformation after 1994, classrooms in South Africa that have previously accommodated learners exclusively from certain homogeneous groups have undergone major changes with regard to learner populations. South African society has become more open and social relations have become less formal (Engelbrecht, Green & Naicker, 1999). However, South African classrooms are no longer as homogeneous as they used to be. Classrooms now host learners of all races, who speak different languages, who have different learning styles, who are at different developmental and intellectual levels, and who are from different socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds, and so on (Alexander, 2010).

Many forums and conferences were held at national and international level promoting the discourse on inclusive education. In 1992 the National Education Coordinating Committee (NECC), working on the basis of a broadly democratic non-racial principle, set about developing proposals for reforming the formal education system into a unitary system of education (NECC, 1997). In addition, the Salamanca Statement on principles, policy and practice in special education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1994) proclaimed that regular schools with an inclusive orientation were the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all. The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994) further decreed that it was beneficial to implement inclusive education in mainstream schools, as it developed cultural awareness, tolerance and communication skills in learners.

The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994) resulted in reforming the South African education system to become more inclusive and beneficial to all, with emphasis on an education system of formal and informal support. Similarly, in Education White Paper 6, it is acknowledged that the early years of a child's life are critical for the acquisition of language (Department of Education [DoE], 2001). Young children learn best through communication by using meaningful social activities to interact with their environment. Education White Paper 6 (DoE, 2001) clearly stipulates that learners who experience barriers to learning in mainstream education classrooms needed to be supported in various ways (DoE, 2001:26). Effective management policy, planning and monitoring capacity to guide and support the development of an inclusive education and training system (DoE, 2001:46) are thus very important for its success.

Despite the measures taken by the DoE to ensure equal, accessible and quality learning opportunities for all learners, many learners still experience barriers to learning because they do not receive the attention or the support that they need in the classroom (Ladbrook, 2009). However, Education White Paper 6 (DoE, 2001) acknowledges that in an inclusive education system all learners can learn and need support. This implies that education structures, systems and learning methodologies should be designed to meet the needs of all learners. This constitutes a challenge for all teachers, as they need to address cultural and language differences in the mediation of the curriculum within the classroom and need support in overcoming these challenges. The success of inclusive education is largely dependent on the support received from teachers, parents and the community. Parental and community support generates a sense of belonging and a feeling of trust that comes from shared experiences. Walton (2011:243) emphasises the role of the community and parents in supporting inclusion, which is characterised by Ubuntu, an ancient African word meaning "humanity to others." This African philosophy of being emphasises cooperation in sharing and understanding: "I am because we are, or I am fully human in relationship with others." Mukuna (2013) asserts that in the South African context the idea of Ubuntu is cited in various texts as a unique indigenous form of being in community with others. The South African democratic society promotes diversity, which in turn promotes an inclusive educational system. Diversity highlights both the strength and tolerance of the community and parents, and the elements of caring, sharing and acceptance. The continuous development and growth of diversity, especially in minority languages in disadvantaged communities, largely depends on the acceptance levels of the majority towards the less developed official languages of the minority (Crystal, 2012).

IsiXhosa-speaking learners in South Africa are members of one minority-language group and they experience challenges in classes where English is the LOLT. Although learners should become proficient in English, the language used in the world of work, isiXhosa learners develop their identity in terms of culture, behaviour and attitudes, and gain a sense of belonging through isiXhosa.

As mentioned above, the environment in South African classrooms has become diverse. This is because learners from diverse backgrounds are in the same class - learners who experience educational barriers, highly advanced learners, learners who under achieve, learners from diverse economic backgrounds and learners with a preferred mode of learning. These factors highlight the responsibility of the Department of Education and parents to address the barriers to learning that some of the dis-advantaged isiXhosa-speaking learners experience in English-medium classrooms (Owen-Smith, 2010). These disadvantaged learners often do not receive support for learning at home. Many of them come from poverty-stricken backgrounds and suffer from malnutrition. As a result, they already lag in the development of their first language. They thus may not have the spoken language skills in their first language that are required to develop reading with comprehension and creative writing skills (Navsaria, Pascoe & Kathard, 2011; Prinsloo, 2011).

Section 29 (2) of the Constitution or the Republic of South Africa (1996), stipulates that all South Africans have the right to be educated in the official language of their choice where that education is reasonably practical (DoE, 1997). However, laws enacted to encourage equity and tolerance of diversity are now becoming conflicting and contribute to barriers to learning for learners, whose primary language is not English, in English-medium classrooms.

There is thus a need to address these challenges that isiXhosa-speaking learners are experiencing, because the South African policy on inclusive education is based on providing education that is appropriate to the needs of all learners regardless of their origins, backgrounds or circumstances (Donald, Lazarus & Lolwana, 2006). South Africa needs to invest in an education system that benefits all its people, but which should also be effective and competitive in the global market.

It is important to consider that the high levels of investment in human capital and a strong education system are drivers of economic growth. Investors are not interested in poor human capital resulting from learning barriers that have not been overcame. Many first-world countries like Germany and Japan can attribute much of their economic success to the heavy investment in human capital (Kim, 2014). South Africa's current level of spending on public education relative to the gross domestic product (GDP) is well above the global average. Investment in training has grown significantly since the implementation of the Skills Development Act (Republic of South Africa, 1998) and the Skills Development Levies Act (Republic of South Africa, 1999). However, in spite of the high level of investment in human capital in terms of education and training, South Africa still has a very high drop-out and failure rate in primary and high schools (Alexander, 2010). South Africa's investment in human capital does not seem very effective in driving its economy to a competitive global market level. Despite the high level of investment in education and training, only half of South African learners who registered for Grade 1 in 2003 progressed to Grade 12 (Spaull, 2015). Based on the results of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), the Department of Education acknowledges that South African children are not able to read at expected levels and are unable to execute tasks that demonstrate key skills associated with literacy (Rule & Land, 2017; Spaull, 2015). Many learners drop out of school because the barriers to learning that they experience are not addressed. This is one of the most important challenges for human resource development in South Africa. South Africa needs to prioritise a strategy for the supply of people who possess priority skills needed to achieve accelerated growth in order to be competitive in the global market. One such skill is proficiency in English, on which meaningful global participation depends.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to investigate the barriers to learning that isiXhosa-speaking learners in the Foundation Phase experienced in classes where English was used as LoLT. This study was guided by the following research question: "What are the barriers to learning that Foundation Phase isiXhosa-speaking learners are experiencing in an English-medium classroom?"

Method

Research Design

A research design is a logical strategy for gathering evidence about knowledge (De Vos, 2005:389). McMillan and Schumacher (2006:9) define research methodology as the ways in which one collects and analyses data. These methods have been developed for acquiring knowledge through credibility, transferability and dependability procedures. This study was a qualitative case study within an interpretivist research paradigm. Interpretivist researchers tend to endow feelings, events and social circumstances with meaning (Terre Blanche, Durrheim & Painter, 2006).

According to Neill (2007 in Yin, 2011:188), the key points of qualitative research are:

• The aim is a complete, detailed description.

• The design emerges as the study unfolds.

• The researcher is the data gathering instrument.

• Subjective individual interpretation of events is important, e.g. uses participant observation, in-depth interviews, etc.

• Data are in the form of words, pictures or objects.

• Qualitative data are more "rich," time consuming, and less able to be generalised.

• The researcher tends to become subjectively immersed in the subject manner.

A case study design is ideal for this type of research because it focuses on context and the lives and experiences of participants (De Wet, 2010). The case study uses multiple sources of evidence as this makes its findings more creditable and authentic (Yin, 2003). We used the qualitative approach to investigate and make meaning of the growing frustration stemming from isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners' challenges in English-medium classrooms in Western Cape schools.

Participants and Setting

The sample for this study was purposively drawn from a population at a historically disadvantaged primary school situated in a disadvantaged area in the Western Cape. South African primary schools provide formal education to children from 6 to approximately 13 years. This particular school was chosen because it was known for the diversity of languages, cultures, and socio-economic backgrounds of its learners. Pilot studies with small groups were conducted to ensure that the questions in the guidelines for the interviews delivered authentic responses.

The participants in the study were 12 Foundation Phase learners (six females and six males aged 7-9), 12 parents/caregivers (of the Foundation Phase learners), and eight Foundation Phase teachers (aged 29-57 years) with various levels of qualifications and experience. All learner participants had isiXhosa as their primary language and used English as LoLT. All teacher participants had been trained to teach through the mediums of English and Afrikaans.

Research Instruments

We conducted two focus group interviews (one with parents and one with teachers) and individual interviews with the Foundation Phase learners. A focus group interview entails that a researcher interviews several participants simultaneously, while an individual interview entails that each participant is interviewed individually (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). We used the focus groups to interview English-speaking Foundation Phase teachers, some of whom were also fluent in Afrikaans (speaking and writing), and isiXhosa-speaking parents, some of whom were also fluent in English (speaking and writing).

The focus group interviews varied from 1 to 2 hours and were held at the school. Individual interviews with learners lasted about 30 minutes. Participants were interviewed more than once to ensure the reliability and validity of the data. On this basis, we established some level of rapport with the participants during the first meeting, at which the aim of the research was explained. Participants were interviewed in a familiar, natural, friendly, educational environment. To facilitate the individual interview process, the researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with all learners. These interviews included some unstructured questions evolving from the interchange between the researchers and each participant, obviously directly relating to the challenges that isiXhosa-speaking learners experience in English-medium classrooms.

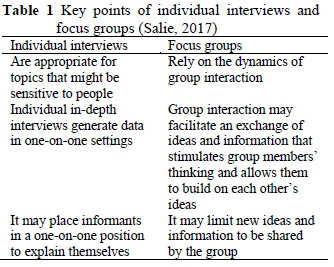

The focus group interviews were very useful because they allowed a space in which the participants with similar interests and concerns were given the opportunity to express their opinions about how they viewed the challenges that their children or learners were experiencing in the English-medium classroom. We ensured that the discussion was not dominated by certain individuals and that each participant in the focus group played an active role in contributing to the discussion. We conducted two focus groups (see Table 1) in order to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. We also employed interpreters to translate the isiXhosa and Afrikaans into English to ensure that the participants understood all the points being raised.

Interviews were chosen as method because of the validity and reliability of the data it produced and the benefits of face-to-face interviews to increase the validity and reliability of the responses (Alshenqeeti, 2014; Bolderston, 2012).

Ethical Considerations

Actions and competence of researchers

De Vos (2005:63) states that much research is undertaken in South Africa across cultural boundaries but emphasises and notes that people do not take the time to get to know and respect one another's cultural customs and norms. In order to obtain the proper co-operation and respect from participants, we researched the participants' culture and customs and discerned how participants might perceive them. We also made concerted efforts to understand and respect the interviewed participants' cultures and customs in an effort to understand the meanings people give to their experiences, culture and customs. We tried to ensure that the analysis of the data collected would be beneficial, not only directly to the research participants, but more broadly to other researchers and society in general. By asking broad questions that allowed the participants to answer in their own words we tried to qualify their understanding through further probing questions. In addition, the interviews allowed the researchers to observe the participants' behaviour, which inevitably increased the reliability and the validity of this study.

We hoped that this study would be beneficial to participants whose primary language was not the LOLT, and to teachers who taught in a language different from the learners' primary language. Furthermore, we hoped that the outcome of this research would serve as some form of guidance to parents in making informed decisions before enrolling their children in schools where the LOLT was not their primary language.

Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of the Western Cape (UWC) and the Western Cape Education Department (WCED). Participants were informed in detail about the nature and objectives of the research. As the learner participants were under 18 years of age, informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. The actual names of the participants and their educational institutions were substituted with pseudonyms to ensure anonymity.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The data were analysed by using a thematic framework proposed by Ritchie and Lewis (2003). This framework was used to classify and organise data according to key themes, concepts and emergent categories. Each category was divided into sub-categories as the data were analysed. Relationships among the categories were established through discovering patterns in the data. We used triangulation, which is cross-validation among data sources and data-collection strategies (McMillan & Schumacher, 2006:374). To find regularities in the data, we compared different sources (parents, teachers and learners), and adopted two methods (interviews with individual learners and focus groups with parents and teachers). At the same time, we looked for discrepancies and negative evidence that might modify or refute a pattern. The developed patterns and themes were then used to report the experiences of the participants. The anonymity of the participants was protected by the use of pseudonyms in the presentation of the results.

Results and Discussion

Data collected in this study show that many isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners who grow up in historically disadvantaged areas and attend disadvantaged schools experience several barriers to learning. These include exposure to isiXhosa communication, psychological-social barriers, cognitive ability challenges, English as language barrier to learning and teaching, and a lack of parental involvement and support.

Participants' Comments Regarding English as Language of Learning and Teaching (LoLT)

Focus groups

Individual interviews

Exposure to IsiXhosa as Primary Language

The participating learners experienced learning barriers because their home language was isiXhosa and the LoLT was English (see Table 2). Many of the participating learners experienced cognitive challenges because of their limited proficiency in English, which was exacerbated by a home environment where limited reading material in English was available. Some of the participants even experienced cognitive stress - not because of lower performance - but because of their limited English proficiency as a result of a lack of exposure to English in their homes. Through observations and access to learners' daily writing materials, tasks and assessments, we noted that many of the participating learners experienced difficulties in reading with comprehension. They were therefore unable to articulate their responses due to their limited English vocabulary and sequencing, grammatical errors in writing and speaking, and difficulties in following and understanding class discussions (see Table 3). In addition, some learners experienced a feeling of isolation in communicating their concerns and views in English. This again led to some of them experiencing anxiety in speaking and reading. This was determined during interviews with the teachers and parents.

You can sense their anxiety especially when they must read from the board ... They struggle with pronunciation which leads to grammatical errors and understanding ... we say bad (naughty) but they say bed (furniture) ... this gives the sentence a total different meaning ... . (Teacher III)

Saito, Horwitz and Garza (1999) indicate that reading in a second language provokes anxiety in some learners who receive instruction in their second-language. They determined that learners' reading anxiety increased in line with their perceptions of the difficulty of reading in a second language. These results were based on research conducted on a sample of 383 French, Japanese and Russian learners in foreign language reading.

We noted that the more anxious the isiXhosa-speaking learners became, the worse their performance in English was. They either stuttered, repeated the question, paused for long periods or just kept quiet. Their lack of proficiency in spoken English constrained them in expressing themselves freely. The learners also tended to suppress information. This led to poor test performances and an inability to perform in class - especially in verbal assessments, which contributed to teachers' inaccurate assessments.

A great deal of research has been conducted to compare the academic performances of learners who were taught in their mother tongue with those taught in a foreign language (English) (Brock-Utne, 2005; Desai, 2003; Langenhoven, 2005). The findings indicate that there was a positive influence in the use of a learners' mother tongue in education in terms of cognitive and affective development, which is similar to Govender's (2010) findings with isiZulu-speaking learners. These findings indicate that isiZulu-speaking learners experienced major problems, including difficulty in using pronouns in sentences, and that they did not interact sufficiently or become involved with more competent speakers of English (Govender, 2010), which contributed to their limited vocabulary and grammar. According to Govender (2010) participating isiZulu-speaking learners had a limited ability to understand the messages that they heard in English, because they were unfamiliar with the use of English vocabulary.

Psychological-Social Barriers

During the interviews we found that participants experienced psychological-social barriers because they were afraid that they would expose their weakness in English, which would label them negatively. These were caused by anxiety and a lack of motivation because of emotions such as fear and nervousness that blurred their thinking and resulted in them failing to organise the message to be communicated. When a message is not organised properly, it cannot be conveyed effectively, which leads to miscommunication. The results from this study indicate that such anxiety and a lack of motivation are related to the use of English as LOLT. It was found that the isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners were experiencing anxiety because of a fear of making grammatical mistakes and answering questions incorrectly. The learners' anxiety stemmed from a desire not to make mistakes when answering questions because their answers were under scrutiny. The learners also experienced reading anxiety when they were asked to read aloud. The learners felt exposed and isolated when their use of English was the focus of attention. One teacher participant remarked as follows: "Yes, they feel isolated because they are too afraid of being snubbed at" (Teacher II).

Blease and Condy (2014) agree that anxiety, insecurity, a lack of motivation and passive learning are psychological-social factors at play in the language usage of learners in classrooms. In addition, Nomlomo's (2007) comparative study reveals self-esteem as a psychological factor that could affect isiXhosa learners when learning English.

English as Language Barrier to Teaching and Learning

The transcripts from participants' responses demonstrate that English was a language barrier to teaching and learning in the Foundation Phase.

Some of the participating parents acknowledged that English was a language barrier to learning and believed that their children's academic performance could have been better had they been taught in isiXhosa. Parents suggested that the school could help their children to navigate their new environment and bridge their learning at school by applying the experiences that they brought from home. Parents argued that this may assist learners to build confidence, to make suggestions, ask and answer questions, and create and communicate new knowledge in their mother tongue. However, parents also argued that learning always started at home in the child's home language and that this played a vital role in their child's life. The parents stated that the mother tongue was important to understand their culture, history and religion. They emphasised that children who were unaware of their culture, language and history might lose their self-confidence. The use of the mother tongue in early education of learners leads to a better understanding of the curriculum content and to a more positive attitude towards school. It further helps them to affirm their cultural identity, which in turn has a positive impact on the way they learn. The use of learners' mother tongue in the classroom promotes a better transition between home and school.

Consequently, when learners start school in a language that they still have to learn, it suppresses their potential and eagerness to express themselves freely. It dampens the spirit, inhibits their creativity, and makes their early learning experience unpleasant. Unfortunately, this negatively affects their learning outcome at a very young age. As a result, parents are aware of the poorer academic performance of their children and suggested that the school should prepare and allow the children to receive their education in their mother tongue, isiXhosa. One teacher explained as follows: "They are so young, yet they never give up trying" (Teacher III).

All participants indicated that the learners were motivated to learn and be taught in English as a second language. One teacher illustrated as follows: "They are so motivated and eager to master English at such a young age" (Teacher V).

These results correlate with those of previous studies, which reported that motivation was identified as one of the key factors in the process of acquisition and achievement and attainment of a second language (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2007).

The results from this study show that most of the participating parents played a big role in encouraging their children to start learning in English. The majority of South African parents prefer that their children are taught in English (Alexander, 2010). This is because many South Africans consider English to be a major international language (Madileng, 2007). As a result, many South African parents feel that it is crucial that their children develop the ability to read, write and listen with understanding, and speak English in order to develop to their full potential (Madileng, 2007). The emphasis on English is essential for people in the non-English speaking world. English language proficiency means opportunities, better jobs, higher salaries and the ability to be able to compete globally (Egan & Farley, 2004). Data from the parents' focus group interviews and learners' individual interviews indicate that the participants regarded English as a superior language for teaching and learning.

"English is good for good jobs" (Parent B). "My child must learn good English to study so that he can get a good job" (Parent F). "English is the language of the world ... the language of opportunity" (Parent J). "English is good for learning. If you can do English, you can go to university" (Learner B). "I study English so that I can buy a house for my family ... a real big house" (Learner K).

A Lack of Parental Involvement and Support Limit Learning

All the teacher participants in this study agreed that a lack of parental involvement and support limited learning. However, most of the teachers felt that it was not their responsibility to involve parents in the learners' learning, but that of the school management team. They indicated that it was very difficult to change the behaviour and attitudes of adults. The teachers also felt that they were already overloaded with work and did thus not have the time to teach parents how to support and guide their children to develop academically. This was a clear indication that most parents were not actively involved in supporting their children's academic development. Nomlomo (2007) argues that parental involvement is related to the parents' own competency and literacy. Nomlomo's (2007) comparative study revealed that parental involvement was more evident in the case of learners who were taught in isiZulu than for those learners who were taught in English. This indicated the link between parental proficiency and learners' effective language acquisition. It allowed the parents to assist their children with schoolwork. Parents who lacked such competence in English could obviously not assist their children with their homework.

Most of the parents indicated a need for support and mentioned that the school should reach out to them to guide then in making wise, informed decisions on how to support their children to achieve academic success. These parents were looking for specific ways to become involved and help their children.

According to Delgado-Gaitan (1990), second-language literacy acquisition activities at home were encouraged by preschool teachers in the United States of America (USA) in the 1990s. Ladky and Stagg Peterson (2008) studied 21 immigrant parents of various educational levels, 61 teachers and 32 principals. They reported on various successful ways of helping children to excel academically in classes where the LoLT was not their home language by involving their parents. The parents played a crucial role in aiding their children to become successful, independent learners.

Conclusion and Limitations, Findings and Future Research

Based on prior and informal research and observations of learning in the Foundation Phase, disad-vantaged South African learners with learning deficits in the Foundation Phase is becoming a big problem. Learners in disadvantaged schools with a lack of parental support and guidance fall further and further behind, which leads to a situation where remediation is almost impossible. The problem is that the gap between what learners should know and what they do know grows bigger and bigger as they progress at school. The learning deficits acquired early in children's school careers become so big that it is difficult for them to catch up. This leads to failure and adds to an already high dropout rate later in school.

Best practices from other countries with similar economic and educational backgrounds should be researched, modified and designed to fit the context of South African schools. The curriculum should aim at developing well-rounded, literate, thinking, caring and skilled adults while actively helping to encourage diversity and gradually accommodating English as LoLT. This process should start in the Foundation Phase using learners' primary language to unlock the curricula. It is well known that learners' learning increases when parents are invited to help learners at home and supporting and volunteering at school. Having enlisted parents' involvement, teachers and administrators can obtain a valuable support system by creating a team working towards each child's success. Parents' and teachers' consultation and collaboration can create a climate for the maximum realisation of a learner's potential. When parents, families and community members are involved with schools, all children benefit. Adult participation indicates that school is important and that the work children do is worthy of adult attention, support and involvement. Effective communication with families and communities means that the school values the support that families give their children. Schools will thus produce learners who will be better prepared to acquire not only knowledge, but also the attitudes and skills to interact positively and productively with people in a diverse democratic South African society.

Some limitations were encountered during this study. The research focused on the experiences of isiXhosa-speaking Foundation Phase learners; this seemed to exclude possible barriers experienced by Foundation Phase speakers of other languages. The influence of correlational dimensions such as school location and poor-quality schools, and how these influence learners' capacity were not investigated.

For future research we recommend a comparative study on the use of curriculum adaptation strategies and how they would be employed in a linguistically and culturally diverse classroom. It should also be researched how South African schools can reach out to parents to create culturally aware school-family partnerships to reduce cultural discontinuities, create diverse learning opportunities, improve ethnic and racial perceptions and attitudes, and foster inter-ethnic friendships that enhance learning. The way in which South African schools can provide parents with the necessary materials and activities that are adapted to accommodate the needs of families from different cultural backgrounds, enhance parental involvement and support and reduce the challenges that children experience in English-medium classrooms should also be researched.

Authors' Contributions

MS wrote the manuscript, conducted the participant focus group interviews and provided data for Tables 1, 2 and 3. MMK revised the manuscript and MKR designed the techniques for data collection and performed qualitative analyses. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. This article is based on the doctoral thesis of Maimona Salie.

ii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

iii. DATES: Received: 23 November 2015; Revised: 26 October 2017; Accepted: 29 August 2019; Published: 31 May 2020.

References

Alexander N 2010. Schooling in and for the New South Africa. Focus, 56:7-13. Available at https://hsf.org.za/publications/focus/focus-56-february-2010-on-learning-and-teaching/schooling-in-and-for-the-new-south-africa. Accessed 6 April 2020. [ Links ]

Alshenqeeti H 2014. Interviewing as a data collection method: A critical review. English Linguistics Research, 3(1):39-15. https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v3n1p39 [ Links ]

Blease B & Condy J 2014. What challenges do foundation phase teachers experience when teaching writing in rural multigrade classes? South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(2):36-56. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajce/v4n2/04.pdf. Accessed 28 April 2020. [ Links ]

Bolderston A 2012. Conducting a research interview. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 43(1):66-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjmir.201U2O02 [ Links ]

Brock-Utne B 2005. But English is the language of science and technology: On the language of instruction in Tanzania. In B Brock-Utne, Z Desai & MAS Qorro (eds). LOITASA research in progress. Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: KAD Associates. [ Links ]

Cheng HF & Dörnyei Z 2007. The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1):153-174. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt048.0 [ Links ]

Crystal D 2012. English as a global language (2nd ed). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Delgado-Gaitan C 1990. Literacy for empowerment: The role of parents in children's education. New York, NY: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Department of Education 1997. Language in education policy. Government Gazette, 18546, December 19. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Education White Paper 6. Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/Specialised-ed/documents/WP6.pdf. Accessed 22 August 2019. [ Links ]

Desai Z 2003. A case for mother tongue education? In B Brock-Utne, Z Desai & M Qorro (eds). Language of instruction in Tanzania and South Africa (LOITASA). Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: E & D Ltd. [ Links ]

De Vos AS 2005. Qualitative analysis and interpretation. In AS De Vos, H Strydom, CB Fouché & CSL Delport (eds). Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human services professions (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

De Wet C 2010. Victims of educator-target bullying: A qualitative study. South African Journal of Education, 30(2):189-201. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v30n2a341 [ Links ]

Donald D, Lazarus S & Lolwana P 2006. Education psychology in social context (3rd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Egan D & Farley S 2004. The many opportunities of EFL training. T+D, 58(1):54-61. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P, Green L & Naicker S 1999. Inclusive education in action in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Govender R 2010. IsiZulu-speaking foundation phase learner's experiences of English as a second language in English medium schools. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/3706/dissertation_govender_r.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 2 April 2020. [ Links ]

Kim S 2014. The challenge of filling the skills gap in emerging economies. Guardian, 7 October. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/oct/07/the-challenge-of-filling-the-skills-gap-in-emerging-economies. Accessed 21 June 2016. [ Links ]

Ladbrook MW 2009. Challenges experienced by educators in the implementation of inclusive education in primary schools in South Africa. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43166301.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2020. [ Links ]

Ladky M & Stagg Peterson S 2008. Successful practices for immigrant parent involvement: An Ontario perspective. Multicultural Perspectives, 10(2):82-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960801997932 [ Links ]

Langenhoven KR 2005. Can mother tongue instruction contribute to enhancing scientific literacy?: A look at Grade 4 Natural Science classroom. In B Brock-Utne, Z Desai & MAS Qorro (eds). LOITASA research in progress. Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: KAD Associates. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2010. Practical research: Planning and design (9th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Madileng MM 2007. English as a medium of instruction: The relationship between motivation and English second language proficiency. MAPL dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/2332/dissertation.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2020. [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S 2006. Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (6th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Mukuna RK 2013. Administration of the adjusted Rorschach comprehensive system to learners in a previously disadvantaged school in the Western Cape. MEd thesis. Bellville, South Africa: University of the Western Cape. Available at https://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11394/4269. Accessed 27 March 2020. [ Links ]

National Education Coordinating Committee 1997. National education policy investigation (NEPI): Support services. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Navsaria I, Pascoe M & Kathard H 2011. 'It's not just the learner, it's the system!' Teachers' perspectives on written language difficulties: Implications for speech-language therapy. South African Journal of Communication Disorders, 58(2):95-104. Available at https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/19939/Navsaria_Article_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 31 March 2020. [ Links ]

Nomlomo VS 2007. Science teaching and learning through the medium of English and isiXhosa: A comparative study in two primary schools in the Western Cape. PhD thesis. Bellville, South Africa: University of the Western Cape. Available at https://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11394/2406/Nomlomo_PHD_2007.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 22 March 2020. [ Links ]

Owen-Smith M 2010. The language challenge in the classroom: A serious shift in thinking and action is needed. Focus, 56:31-37. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ba57/ff0758c5e4b9939ad71913a6735055c82c25.pdf. Accessed 27 March 2020. [ Links ]

Prinsloo CH 2011. Linguistic skills development in the home language and first additional language. Paper presented at a seminar of NRF-funded consortium for "Paradigms and Practices of Teaching and Learning Language", Pretoria, South Africa, 11-12 March. Available at http://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/3758/6860.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 19 April 2020. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of1996). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1998. Act No. 97, 1998: Skills Development Act. Government Gazette, 401(19420), November 2. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1999. Act No. 9, 1999: Skills Development Levies Act. Government Gazette, 406(19984), April 30. [ Links ]

Ritchie J & Lewis J (eds.) 2003. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Rule P & Land S 2017. Finding the plot in South African reading education. Reading & Writing, 8(1):a121. https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v8i1.121 [ Links ]

Saito Y, Garza TJ & Horwitz EK 1999. Foreign language reading anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 83(2):202-218. https://doi.org/10.1111/00267902.00016 [ Links ]

Salie M 2017. Investigating the importance of parental support in enhancing academic achievement in foundation phase learners. PhD thesis. Belville, South Africa: University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Spaull N 2015. Schooling in South Africa: How low-quality education becomes a poverty trap. In A De Lannoy, S Swartz, L Lake & C Smith (eds). South African Child Gauge 2015. Cape Town, South Africa: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. Available at http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/367/Child_Gauge/South_African_Child_Gauge_2015/ChildGauge2015-lowres.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2020. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche M, Durrheim K & Painter D (eds.) 2006. Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences (2nd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town Press (Pty) Ltd. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain, 7-10 June 1994. Paris, France: Author. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427. Accessed 19 April 2020. [ Links ]

Walton E 2011. Getting inclusion right in South Africa. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46(4):240-245. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1053451210389033 [ Links ]

Yin RK 2003. Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2011. Applications of case study research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]