Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1664

ARTICLES

A proverb in need is a proverb indeed: Proverbs, textbooks and communicative language ability

Çiler HatipoğluI; Nilüfer Can DaşkınII

IDepartment of Foreign Language Education, Faculty of Education, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey ciler@metu.edu.tr

IIDepartment of Foreign Language Education, Faculty of Education, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey

ABSTRACT

In the study reported here we focus on proverbs in English Language Teaching (ELT) coursebooks and how the pithy structure and the "wisdom"-loaded content of proverbs can contribute to the development of foreign language learners' communicative competence as defined by Bachman (1990). We discuss how the most frequently used coursebooks in the context of English as a foreign language (EFL) were identified through a questionnaire administered to 127 first and fourth-year EFL pre-service teachers. We also show how these popular coursebooks were scrutinised for the inclusion and presentation of proverbs by using content analysis and an analysis form to uncover (1) the number of the proverbs incorporated, (2) whether or not the presentation of the proverbs in the coursebooks would foster the development of the competencies identified by Bachman (1990), and (3) whether they were among the most known and frequently used proverbs in present-day English (i.e., currency). The findings reveal a number of problems related to the frequency and currency of the included proverbs, and to the adequacy of the presentation of the proverbs in the examined coursebooks to help studentsi develop their communicative competence.

Keywords: communicative competence; ELT textbooks; proverbs; teaching English

Introduction

Nowadays, it is widely accepted that to achieve (intercultural) communicative competence (CC) in a target language, it is not sufficient to master the grammar of the language in isolation from its cultural context (Byram, Gribkova & Starkey, 2002; Corbett, 2003). According to Bachman's model (1990:87), the framework adopted in the study reported here (Bachman's Model of Communicative Competence [BMCC]), learners need to develop both their organisational (i.e., grammatical and textual competences) and pragmatic competences (i.e., illocutionary and sociolinguistic competences) (see Appendix B). Proverbs are an integral part of the cultural references and figurative language within the sociolinguistic competence, and despite being "ubiquitous" (Steen, 2014:118), they are usually neglected in foreign language teaching (FLT) and FLT materials. Litovkina (2000) points to the fact that proverbs are rarely incorporated in the FL classes and are usually used as time-fillers and not studied in context. Proverbs are commonly associated with culture teaching (Bessmertnyi, 1994; Çakir, I 2006; Can Daşkın, 2011; Ciccarelli, 1996; Hendon, 1980; Richmond, 1987; Yano, 1998), and their contribution to the development of many of the competences indicated in Bachman's CC model remains understudied.

Littlemore and Low (2006a, 2006b) demonstrate, however, how figurative language could play an important role in the development of each of the components in Bachman's framework. Since metaphors are a rich and diverse category (Botha, 2009), and each of their sub-types requires special attention, our first aim with this study was to show that proverbs (as conventional metaphors) have features that can be utilised to enhance not only cultural competence, but also overall CC. Following these discussions, our second goal was to identify the extent to which textbooks incorporate proverbs in a way that would foster the development of the communicative language ability of language learners. To do this, the use of proverbs in local and international EFL textbooks used in Turkey were examined quantitatively and qualitatively, and the manner and purposes of their presentation in these materials were discussed with reference to BMCC. In the study we focused on coursebooks in an EFL setting, since research in these contexts shows that coursebooks are still the most widely used tools in language instruction, and that few teachers enter class without them (Allen, 2015; Can Daşkın & Hatipoğlu, 2019; Jafarigohar & Ghaderi, 2013; Kayapinar, 2009; Ötügen, 2016; Sadeghi & Richards, 2015; Swe, 2017). Books are sometimes even viewed as providers of readymade syllabi (i.e., content and teaching/learning activities) for teachers and can shape much of the practices in language classrooms (Batdı & Eladı, 2016; Engelbrecht, 2008; Kayapinar, 2009; Wall & Horák, 2011).

Many experts (Amuseghan & Olayinka, 2007; Ohia & Adeosun, 2002; Sackstein, Spark & Jenkins, 2015) argue that frequently there is "'uncritical reliance' on the authority of these sources and that the books are not properly examined, analysed and evaluated before selection for use in the classroom" (Amuseghan & Olayinka, 2007:179). Therefore, the selected books often do not include enough materials to help students develop their CC at maximum level, and this, in turn, usually has a negative impact on the quality of language learning. By focusing on proverbs in coursebooks, we aimed to extend the discussion initiated by Littlemore and Low (2006a) by referring to more specific examples (i.e., proverbs) and to set a model for studying, not only the proverbs, but also other metaphorical expressions in relation to the development of CC.

Proverbs

Proverbs are defined in various ways by different groups of researchers (D'Angelo, 1977; Dundes, 1975; Giddy, 2012; Harnish, 1993; Mieder, 2004; Milner, 1971; Norrick, 1985; Ulusoy Aranyosi, 2010). One group of experts take a structural approach and describes proverbs as propositional statements including at least a topic and a comment (Dundes, 1975; Milner, 1971). Others approach them from ethnographic and (super) cultural perspectives and state that proverbs are typically spoken, conversational forms whose sources are not known and which usually have a didactic function (Giddy, 2012; Norrick, 1985; Ulusoy Aranyosi, 2010). Still, others prefer to follow an empirical approach, which helps them to derive and/or modify their definitions (Mieder, 2004).

In this study, the definition proposed by Mieder (2004:3) was adopted. This definition is more inclusive when compared to the others and it is empirically derived (i.e., it is based on the views of the native speakers (NS) of American English):

A short, generally known sentence of the folk which contains wisdom, truth, morals, and traditional views in a metaphorical, fixed and memorisable form and which is handed down from generation to generation.

Literature Review

Proverb instruction in second/foreign language (L2) classrooms has been studied from various perspectives. Some of these studies have employed questionnaires to uncover instructors' or students' attitudes to and/or experiences of the teaching and learning of proverbs. For example, using a questionnaire, Hanzén (2007) uncovered that teachers had a positive attitude towards using proverbs in English language teaching. In another study, Liontas (2002) explored L2 learners' and EFL student-teachers' thoughts about idiomaticity in a more general sense. He showed that learners were aware of the important role of idioms in communication and expressed a desire and interest in learning them. He also found that the learners were not given explicit instruction on idioms and were not happy with their knowledge of idioms. By administering a questionnaire to EFL student-teachers, Can Daşkın and Hatipoğlu (2019) uncovered important information regarding their proverb learning experiences in high school. EFL student-teachers had a positive attitude towards the instruction of English proverbs, however, they thought that their English teachers and the coursebooks they used in high school were not sufficient for teaching proverbs. They also expressed discontent with their knowledge of English proverbs. Other studies suggest activities for and approaches to the teaching of proverbs (e.g., Çakir, A 2016; Göçmen, Göçmen & Ünsal, 2012; Gözpınar, 2014).

Closely related to the scope of this study are those which have analysed FLT materials in terms of proverb use, even though they are, to the best of our knowledge, limited in number. Among them are studies conducted by Hanzén (2007), Turkol (2003), and Vanyushkina-Holt (2005) who scrutinised textbooks employed in specific countries, and attempted to identify the groups of proverbs included in the books and the ways in which they were presented to learners. Vanyushkina-Holt (2005) examined 20 randomly selected textbooks used to teach Russian as a foreign/second language and found that Russian proverbs were underestimated and underrepresented in these materials. She further indicated that even though some textbooks included a reasonable number of proverbs, they were not presented effectively and/or explicitly.

Hanzén (2007) reviewed 11 randomly selected textbooks used in English A and English B courses at seven upper secondary schools in Sweden and found that few proverbs were used in EFL teaching. Similarly, Turkol (2003) scanned dozens of popular Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) books and encountered "proverbs" as an index item only in one of the books where proverbs were incorporated along with rhymes, poems and songs to improve students' speaking skills, but the functions of proverbs in communication were not discussed.

In contrast, Alexander (1984) analysed 13 dictionaries and reference books in terms of the eight types of fixed expressions in English, one of which consisted of proverbs and proverbial idioms. His study showed the extent to which the scrutinised coursebooks covered fixed expressions and made a comparison among them for teachers and learners. Lázár (2003), who introduced Mirrors and Windows as an intercultural communication textbook, indicated that the book included examples of proverbs, idioms, and sayings from various cultures for comparison in the language section of each unit to show the reflection of culture in language. Finally, Koprowski (2005) analysed three contemporary English coursebooks with regard to the usefulness of lexical phrases, which included idiomatic expressions. With reference to corpus data that shows the frequency and range of the phrases, he shows that the multi-word lexical items included in coursebooks are not useful and may have limited pedagogical value.

Only three studies indirectly focused on proverbs in coursebooks employed in Turkey. In 2010, I Çakir quantitatively analysed three English coursebooks used in primary schools in Kayseri/Turkey in terms of culture-specific expressions and cultural references such as festivals, idioms, proverbs, superstitions, et cetera. He reports that very few cultural elements with a limited number of proverbs were included in the examined textbooks. Similarly, Arıkan and Tekir (2007) asked teachers and students to assess the quality of a local English coursebook, Let's Speak English 7. Teachers evaluated the book negatively arguing that it should have contained more cultural expressions and vocabulary such as proverbs and idioms. Lastly, in a rather different study, Khan and Can Daşkın (2014) investigated EFL student-teachers' use of idiomatic expressions, which included proverbs, in in-house instructional materials they had designed for a course. They found that the student-teachers' use of idiomatic expressions was inadequate in quantity and quality as the ways in which the few idioms were presented were pedagogically not successful at enhancing learners' communicative competence.

Building on previous research and following up on the authors' earlier study (Can, 2011), which also offers the baseline of this study, we systematically scrutinised a wide range of popular local and international EFL coursebooks in terms of the quantity and quality of proverbs used with reference to BMCC.

Method

Research Questions

We used the following research questions to guide this study.

1.What is the role of proverbs in developing each of the competencies in BMCC?

2.How are the proverbs in the examined coursebooks presented to the learners?

a.How many proverbs are included in the most popular coursebooks used in Turkish high schools?

b.What kinds of competencies can the use of proverbs in the examined coursebooks develop?

3.How many of the proverbs contained in the EFL coursebooks are among the proverbs that are frequently used/commonly known by NS of English?

Participants

One hundred and twenty-seven first and fourth-year students aged between 18 and 20 years at the Departments of Foreign Language Education (i.e., pre-service teachers) in two top-ranking state universities in Turkey participated in this study. The participants graduated from various high schools all over Turkey and were advanced users of English as they had been learning the language for more than ten years. Many of the participants were from low-income working families. Only 29% of the participants' fathers and 12% of mothers held tertiary qualifications. These conditions, it seems, led to limited educational opportunities for the participants (e.g., taking extra language courses, using technology to improve their language proficiency, going abroad for educational or any other purpose). Only 25% of the students had been to foreign countries; mostly to the United States of America (USA) (due to the popularity of "work and travel" programmes), the United Kingdom (UK) and Germany, and the majority stayed there for two to six months. The bulk of the participants' language-learning experiences were limited mainly to their language classes.

When asked, most of the students (68%) stated that coursebooks were the sole materials employed for proverb teaching in their FL classes. Only 32% indicated that their teachers used additional supplementary materials (e.g., videos, songs, worksheet, lists, proverb dictionaries).

Furthermore, as is evident from Appendix A, most of the participants reported that they rarely or never interacted with NS of English (Items b-f in Appendix A), read newspapers (Item i) and books in English (Item j), listened to English programmes on the radio (Item k), or watched TV news in English (Item g). The only activities in which they engaged relatively often were listening to English songs (Item l), surfing English websites on the internet (Item m), and watching movies and English TV channels (Items h and a). The findings of this study were consistent with the results of a study conducted by Hatipoğlu (2009:347) who also found that the majority of pre-service EFL teachers in Turkey "never have face-to-face conversations with, or write to or receive e-mails from native speakers" of English.

The data from the questionnaires highlighted the significance of EFL classes and coursebooks in Turkey. Most of the participants were exposed to English predominantly in the classroom and the coursebooks were the only/main teaching materials. Therefore, it could be argued that the coursebooks had a considerable influence on what teachers taught in class and how they did it (Cunningsworth, 1995; Koprowski, 2005; Sadeghi & Richards, 2015; Swe, 2017). All this underlines the importance of the selected coursebooks for the success of language education in the country, which is why we focused our analysis on the most frequently used coursebooks in Turkish high schools.

Data Collection

To answer the first research question, in-depth scrutiny of the available literature was conducted. Then, a questionnaire comprising two parts was adapted from Can (2011) for the purposes of this study and was used to collect data from the participants. The questions in Part 1 of the questionnaire gathered detailed background information about the participants (i.e., age, gender, schools they graduated from, their language learning experiences, self-evaluated proficiency level, level of education of the parents, monthly family income). The questions in Part 2 were intended to identify the coursebooks (i.e., names, levels) and other teaching materials used by high school teachers in EFL classrooms in Turkey.

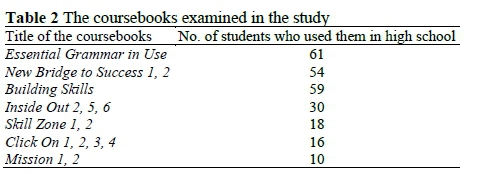

Data Analysis

Our aim with the quantitative analysis of the questionnaire data was to identify the commonly employed coursebooks in Turkish high schools. After the analysis of the questionnaire data, the 15 most frequently employed EFL coursebooks in Turkish high schools were identified and examined (Table 2). Our analysis focused on the books used in Turkish high schools because the university entrance exam is based on the curriculum and materials covered in Turkish high schools and determines to which universities and departments students are accepted (Hatipoğlu, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2017).

Step 2 in the analysis was scrutinising coursebooks for proverb use. In doing this we followed Mieder's (2004) definition of proverbs, and several proverb dictionaries and lists prepared by researchers such as Haas (2008), Hirsch, Kett and Trefil (2002), Hornby (2000), Ridout and Witting (1969), Simpson and Speake (2003) were used as reference material. All proverbs in the books were identified following detailed reading and content analysis techniques. It was not possible to utilise any of the known search programs, as the authors did not know which of the many proverbs would be found in the examined coursebooks.

The content analysis was done using the analysis form adapted from Can (2011) (see Appendix C). For each proverb identified, detailed information about where (e.g., unit title, grammar section, speaking section, etc.), how (e.g., matching activity, discussion, translation, in a text, etc.) and for what purpose (e.g., to practise the target grammar point, to teach culture, etc.) the proverb was incorporated, was entered in the form.

As part of the analysis form, the use of the identified proverbs was classified following the categories in BMCC. Through the analysis we identied the frequency of use, which competences could be develop through their use, and whether the proverbs were among the most known/most frequently used by NS of English.

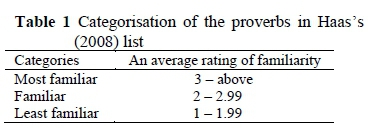

The reference list including the most known/commonly used proverbs in oral and written interactions in a language is known as the "paremiological minimum" (Mieder, 2004). The paremiological minimum forms part of the cultural literacy of NS and is very important for FL instruction (Mieder, 2004). Considering the English language, a precise paremiological minimum is not known, but Haas (2008) established a descriptive paremiological minimum for English. She asked college students from four regions in the USA to complete proverb generation and proverb familiarity tasks and found that proverb familiarity was stable across the studied regions. The list of proverbs derived at the end of her study is called the "descriptive paremiological minimum" (Haas, 2008:328). Haas's (2008) list was used for the analysis of the proverbs in this study. Proverbs were classified as shown in Table 1 and noted in the analysis form.

In this way, rather than following the impressionistic method that involves subjective evaluation, the analysis form was used in order to achieve a more objective and principled evaluation of the coursebooks as well as to yield an in-depth analysis. In this respect, Tomlinson (2003:23) affirms that "making an evaluation criterion-referenced can reduce subjectivity and can certainly help to make an evaluation more principled, rigorous, systematic and reliable."

Results and Discussion

Proverbs and Bachman's Model of Communicative Competence (BMCC) (1990)

Based on a detailed critical review of the available studies, in this section we aim to show how proverbs can contribute to the development of the four competences listed in BMCC. We focus on BMCC since it emphasises all language skills and components equally, which, in our opinion, is vital for the EFL contexts where the development of the grammatical and textual competences is sometimes deemed more important than the development of intercultural awareness (Hatipoğlu, 2012, 2013, 2016; Lenskaya, 2013; Loumbourdi, 2014).

As is evident from Appendix B, CC in Bachman's (1990) model consists of two main components: Organisational Competence (OrgC) and Pragmatic Competence (PragC). Under OrgC, Bachman lists two sub-competencies: Grammatical Competence (GrC) and Textual Competence (TextC). Studies done in various contexts show that proverbs can be used to develop both (Abu-Talib, 1982). Proverbs are practical tools that can be employed to teach vocabulary (because they stick in learners' minds), to exemplify and practice grammar points, to show creative use of language, and to teach and practice pronunciation due to their musical quality (Babiker, 2017; Hallin & Van Lancker Sidtis, 2017; Holden & Warshaw, 1985; Nuessel, 2003; Rowland, 1926; Yurtbaşı, n.d.). That is, when utilised appropriately, proverbs can pave the way for the improvement of language learners' GrC.

Proverbs are powerful rhetorical devices and may, through their use, contribute to the development of TextC and effective spoken/written communication (Vanyushkina-Holt, 2005; Weigle, 2013). Studies in applied linguistics demonstrate that competent writers/speakers regularly use proverbs in topic transition sequences and/or at the beginning/end of their texts to introduce or summarise an idea (Drew & Holt, 1998; Irujo, 1986; Littlemore & Low, 2006a; Obeng, 1996; Vanyushkina-Holt, 2005).

In Bachman's (1990) CC model, PragC is also divided in two sub-categories: Illocutionary Competence (IllocC) and Sociolinguistic Competence (SoclC). IllocC "refers to one's ability to understand the message behind the words that one reads or hears or to make clear one's own message through careful use of words" (Littlemore & Low, 2006a:112). It also consists of ideational, manipulative, heuristic and imaginative functions. Research has shown that NS frequently utilise proverbs to perform these functions in everyday interactions. By employing proverbs, they carry out indirect speech acts and make their speech more polite (Mieder & Holmes, 2000; Norrick, 2007; Obeng, 1996; Searle, 1975), give advice, educate, persuade, and embellish their speeches and writings (D'Angelo, 1977; Weigle, 2013). Proverbs also help us to "strengthen our arguments, express certain generalizations, influence or manipulate other people, rationalize our own shortcomings, question certain behavioural patterns, satirize social ills, poke fun at ridiculous situations" (Mieder, 1993:11). Due to the flexible nature of proverbs, speakers manipulate them and generate anti-proverbs that are used to create humour, irony, and jokes (Litovkina, Mieder & Földes, 2006; Mieder, 2004). All these illustrate how teaching proverbs can contribute greatly to the development of FL learners' IllocC.

SoclC in BMCC (Bachman, 1990) includes sensitivity to dialect, register, naturalness, as well as the ability to interpret cultural references and figures of speech. Studies show that proverbs are used by NS as "a significant rhetorical force in various modes of communication" (e.g., friendly chats, powerful political speeches, best-seller novels, influential mass media) (Mieder, 2004:1). Therefore, the teaching of proverbs is important for the enhancement of learners' sensitivity to dialects and registers.

Proverbs can also facilitate the improvement of students' sensitivity to naturalness (Prodromou, 2003; Sinclair, 1992; Wray, 2000; Yorio, 1980). Research reveals that non-native speakers (NNS) and language learners avoid using idiomatic expressions and prefer literal and direct language (O'Keeffe, McCarthy & Carter, 2007) which gives their "language a bookish, stilted, unimaginative tone" (Cooper, 1999:258). Since proverbs are part of the formulaic language, good knowledge of these can lead to more fluent, more natural language production, which, in turn, can increase students' motivation to learn the target language (Porto, 1998). Therefore, the teaching/learning of idiomatic expressions is crucial if the aim is to accomplish command of more authentic language.

Proverbs "capture the heart of human experience" (Holden & Warshaw, 1985:63); they are part of cultural literacy and express the shared knowledge, values, history, and thoughts of a nation (Hirsch et al., 2002). Therefore, the teaching/learning of proverbs in EFL classes can lead to the improvement of the cultural and cross-cultural sensitivity of FL learners. By examining the use of proverbs in various contexts, learners gain insight into how NS conceptualise experiences, objects, and events (Bessmertnyi, 1994; Ciccarelli, 1996; Kuimova, Uzunboylu & Golousenko, 2017; Richmond, 1987; Yano, 1998), and are able to compare and contrast native and target cultures.

Many of the existing proverbs are figurative language items as they are usually metaphorical and contain prosodic devices (Babiker, 2017; D'Angelo, 1977; Lakoff & Turner, 1989; Mieder, 2004; Norrick, 1985; Ridout & Witting, 1969). Hence, they can be used to prompt "figurative thinking" and enhance metaphoric competence (Littlemore & Low, 2006a). In this way, learners' understanding of not only the literal but also the non-literal meanings of expressions can be enhanced.

Following the discussions above it can be claimed that the teaching/learning of proverbs can improve not only OrgC but also PragC and consequently CC of learners since "proverbs and the metaphors contained in them comprise a microcosm of what it means to know a second language" (Nuessel, 2003:158). These expressions require both the knowledge of linguistic structures and the sociolinguistic and discourse factors. That is why Litovkina (2000:vii) argues that

[t]he person who does not acquire competence in using proverbs will be limited in conversation, will have difficulty comprehending a wide variety of printed matter, radio, television, songs, etc., and will not understand proverb parodies which presuppose a familiarity with a stock proverb.

How are the Proverbs in the Examined Coursebooks Presented to the Learners?

To empirically test BMCC by evaluating the use of proverbs in teaching materials, the coursebooks used by 10 or more of the participants in our study were analysed (Table 2). A total of 15 locally and internationally published coursebooks were examined. An example of a local coursebook written by Turkish teachers of English specifically for Turkish learners was New Bridge to Success (NBS) while books such as Inside Out, Skill Zone, Mission and Click On are international coursebooks.

How many proverbs are included in the most popular coursebooks used in Turkish high schools?

The examined books included 136 proverbs but the frequency of proverb use changed from one coursebook to another (see Figure 1), and the mean of proverb use per book (M = 10.5) can be said to be quite low despite the fact that proverbs are frequently used in authentic interactions (Ellis, 2008). Moreover, considering that each of the examined coursebooks in the sets consists of at least 10 units and 150 pages, it can be argued that proverbs are not given adequate space in these. Therefore, in terms of quantity of proverbs, the coursebooks do not seem to be representative of real-life language use. Besides, the large type-token ratio (TTR = 0.91) shows that the same proverb is rarely recycled in the coursebooks, which limits students' opportunities to revise and learn those proverbs.

Among the examined coursebooks, the Click On series was the set that included a relatively higher number of proverbs, which may be due to the nature of the set. Click On extensively presents everyday language mostly in the form of dialogues while Mission, Inside Out and Building Skills focus mainly on literal meanings and written language. The high number of proverbs in Click On was a positive finding, showing that writers had tried to represent language realistically since proverbs are an important part of the oral tradition of English (Dundes, 1975; Ellis, 2008; Friesen, 1978; Nnolim, 1983).

Conversely, no proverbs were found in Skill Zone 1 and Inside Out 2, and only one proverb was included in each of the coursebooks Click On 1, Click On 2, New Bridge to Success 2 and Essential Grammar in Use. Apart from the results related to Click On 3 and 4, and Inside Out 5, the findings related to the remaining 12 books are consistent with the results of the previous studies in which it was found that the analysed FL coursebooks incorporated a limited number of proverbs (Çakir, I 2010; Hanzén, 2007; Turkol, 2003; Vanyushkina-Holt, 2005).

What kinds of competencies can the use of proverbs in the examined coursebooks develop?

Quantity alone is not enough to determine sufficiency in terms of proverb instruction. The way proverbs are presented is equally important. Therefore, one of our objectives with this study was to uncover what kinds of competences, as identified in BMCC, could potentially be developed by the ways in which the proverbs were presented in the coursebooks.

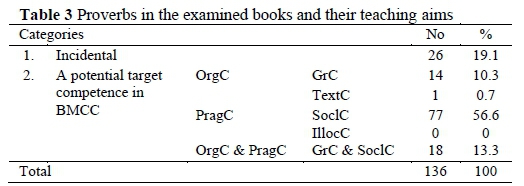

Of the 136 proverbs included in the coursebooks, 19.1% were incidental (Table 3). They were usually given as unit (sub-)titles, as part of the reading and listening texts, or as a list in a separate section without any exercises/questions related to them (i.e., the development of none of the competences indicated in BMCC was targeted) (see Example 1).

Example 1 Incidental proverb presentation "A healthy mind in a healthy body" à given only as a unit title in Click On 3.

With regard to proverbs given incidentally, Vanyushkina-Holt (2005) maintains that students either do not notice them or skip them as unimportant details since such a use of proverbs is suitable for NS who can recognise and understand them automatically. Even though integrated in the coursebooks, the burden of making use of such proverbs is on the students and the teachers. Unless the students have special interest in learning proverbs or the teachers spare precious class time to explicitly introduce them, incidental proverbs are not learned.

One hundred and ten (80.9%) of the proverbs were taught explicitly in the coursebooks. The bulk of those (70%, 77/110) were directed towards students' SoclC while no proverbs focusing on the development of the IllocC were encountered. This shows that none of the examined coursebooks dealt with the underlying messages and functions (e.g., ideational, manipulative) of proverbs.

The SoclC in BMCC (i.e., the most popular competence in the studied coursebooks) comprises four sub-competences: (i) sensitivity to dialect, (ii) sensitivity to register, (iii) sensitivity to naturalness, and (iv) ability to interpret cultural references and figures of speech. Scrutiny of the selected books showed exercises focusing on the interpretation of cultural references and figures of speech (i.e., sub-competence iv), but no section in the examined books was devoted to the first three sub-competences identified by Bachman (1990). In the majority of the exercises aiming to develop learners' ability to interpret cultural references, students were asked to discuss the meaning(s) of the proverbs. Most of these exercises (N = 55) appeared in the writing sections of the coursebooks (e.g., in Click On 3 and Click On 4 students were asked to read and discuss the given proverbs) while a relatively smaller number (N = 17) formed part of the reading sections. Only in Skill Zone 2, proverbs (N = 3) were incorporated in the speaking sections and differently from the other coursebooks, students were asked not only to discuss these proverbs, but also to compare them with their native culture (i.e., exercises developing students' ability to interpret cultural references) (see Example 2). On the other hand, there was only one reference to the figurative aspect of proverbs. In Inside Out 5, the proverb "Time is money" was given as a metaphor based on which some expressions were taught, and the idea that some expressions contained the same underlying conceptual metaphor was emphasised. The scarcity of reference to the figurative aspect of proverbs uncovered in this study supports Tomlinson (2003) who argues that the expressive and poetic functions of the language are ignored in language teaching materials.

Example 2 Proverb instruction related to the "ability to interpret cultural references" as part of SoclC "Money is the root of all evil," "Money doesn't grow on trees," "Money is a terrible master but an excellent servant"

given in the speaking section of Skill Zone 2. Students are required to discuss the meaning of these proverbs and compare them to the relevant proverbs about money in their own language.

Only 15 of the identified proverbs (11%) were aimed at developing students' OrgC. Among those, 10.3% (N = 14) targeted the development of GrC. Half of these proverbs were located in the vocabulary sections of the books where the main aim was to teach the proverbs themselves (see Example 3). The other half was placed in the grammar sections, where the proverbs were used to teach and practice certain grammar points or to test learners' grammatical knowledge (see Example 4). The exercises in both of those sections were mechanical (e.g., fill-in-the-blanks, matching). Apart from those, only one of the proverbs was aimed at developing the students' TextC. In Mission 1 learners were encouraged to use proverbs as a writing strategy in an exercise where they were instructed to use a proverb to end their essays. The small number of proverbs in the OrgC category was an unexpected finding as many studies describe how effective proverbs could be in teaching grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation (Babiker, 2017; Hallin & Van Lancker Sidtis, 2017; Holden & Warshaw, 1985; Nuessel, 2003), and textual organisation (Drew & Holt, 1998; Littlemore & Low, 2006a; Mieder, 1993; Obeng, 1996).

Example 3 Proverb instruction related to "vocabulary" as part of GrC

"Like father like son"

given in the revision section of Click on 4 for the students to fill in the blanks in the proverb to learn the complete form.

Example 4 Proverb instruction related to "syntax" as part of GrC

It used to be said that "beauty was in the eye of the beholder"

given in the grammar section of Inside Out 5 to exemplify passive report structures.

"Time is money" à given in the grammar section of Inside Out 5 as an example for general statements in which the definite article is not used with plural or uncountable nouns.

Through our examination of the coursebooks, we uncovered a small number of examples (13.3%) where proverbs were used to potentially develop more than one of Bachman's competencies simultaneously. These included cases in Click On 4 and Inside Out 5, where the same proverb was used to develop both GrC and SoclC. For example, some of the proverbs (N = 6) in the vocabulary sections of Click On 4 were aimed at teaching not only their structure and meaning, but also encouraging students to interpret them. Similarly, proverbs included in the pronounciation section of Inside Out 5 (N = 12) aimed at teaching vowels, but the students were also asked to discuss the meaning of these proverbs (see Example 5). Consequently, these instances are good examples of how proverbs in coursebooks could help students to improve their vocabulary and pronunciation (i.e., GrC) while also developing their SoclC by asking them to interpret such cultural references.

Example 5 Proverb instruction related to both GrC and SoclC

"Charity begins at home," "Blood is thicker than water," "Home is where the heart is," "Birds of a feather flock together," etc.

given in the pronunciation section of Inside Out 5 with underlined single vowel sounds. Students were to listen to the proverbs to write the phonetic symbols of the underlined single vowel sounds and then to match them with their meanings given in the following section. In the last section, students were asked to choose the proverb they liked best and discuss their choice with a partner.

The overall analyses show that the use of proverbs in the examined coursebooks could moderately help learners develop SoclC and GrC (to a lesser degree), but not TextC (there was hardly any reference to the role of proverbs in the organisation of texts) or IllocC, even though proverbs are an important part of all these competences. The examined coursebooks displayed partial focus on the meaning and structure of proverbs but not on their interactional functions (i.e., no information about how, where, when and in interaction with whom they could/should be used). This distribution is problematic because proverbs are functional units and knowing their linguistic structure is not sufficient to enable students to use them successfully. Students will not be able to benefit from proverbs if they are not aware of the rules specifying their usage (Nuessel, 2003). Even though the number of proverbs aimed at developing SoclC was relatively higher, many of the aspects related to this competence were neglected. For instance, in most of the analysed coursebooks the metaphorical or figurative aspects of proverbs were underestimated as they were only included as examples of accurate structures or as examples of vocabulary items. In addition, although students were encouraged to discuss the meaning of proverbs, little indication of any cultural explanation to guide these discussions was given and no systematic analysis across different cultures, which could have contributed to the development of students' intercultural communicative competence (ICC), was provided (Can Daşkın, 2011). This finding was in line with the result of a study by Byrd, Cummings Hlas, Watzke and Montes Valencia (2011) who claim that teachers'/students' perspectives as part of cultural dimensions are neglected more often than cultural products and practices. They maintain that "understanding underlying cultural attitudes and beliefs and knowing how to teach them is a challenging task and one that deserves more professional attention" (Byrd et al., 2011:22). Therefore, we argue that ELT books should include more exercises that encourage learners to analyse proverbs across different cultures more systematically so that they can have access, not only to the NS' culture, but also to other world cultures. Doing this, we hope, will equip learners with skills enabling them to discover and interpret their own and other cultures, and will help them become independent intercultural analysts and interpreters.

The general findings of this study are parallel to the results of other studies on coursebook evaluation. Hanzén (2007) reports that the coursebooks examined in her research included proverbs mainly for discussion, in different types of texts, like headings or/and examples of grammar. Likewise, Vanyushkina-Holt (2005) found that proverbs were not given in ironic and humorous contexts in the analysed textbooks, even though some textbooks used proverbs in lists, titles, as examples for certain grammar topics, and as invitations to discussions, the included proverbs were usually not the point of focus. Few textbooks offered cultural explanations regarding the proverbs, and most of them did not investigate the figurative meanings of proverbs. Moreover, Turkol (2003) shows that the few proverbs she encountered in one of the coursebooks were incorporated along with rhymes, poems and songs to improve speaking skills, but their functions in communication were not discussed. It can be argued, therefore, that the examined textbooks usually fail to include information related to the pragmatic use of proverbs (Campillo, 2008).

The findings of this study, also, support Tomlinson's (2003:431) claims that (1) there is a return to the central place of grammar in the language curriculum, (2) there are few attempts in published materials to focus on the ways in which linguistic choices are constrained by setting, situation, status, and purpose, and (3) "tasks requiring oral interaction tend to be situated in neutral, culture-free zones, where the learner is only called upon to 'get the message across.'"

How many of the proverbs contained in the coursebooks are among the proverbs that are frequently used and commonly known by NS of English?

Together with the quantity and quality of proverb use in the examined coursebooks, the currency of these expressions was considered in this study because it is crucial that teachers and material designers select the proverbs that are well known/ frequently used today for teaching.

The results given in Figure 2 show that 45% (N = 61) of the proverbs included in the examined books were not included in Haas's (2008) descriptive paremiological minimum. Among the remaining proverbs, 26% (N = 36) were among the most familiar, 13% (N = 18) were among the familiar and 13% (N = 18) were among the least familiar proverbs in the paremiological minimum. A small number (N = 15, 11%) of the proverbs in the examined coursebooks were among the generated ones (i.e., proverbs that are re-produced/altered by NS of English).

The analyses given above show that many of the proverbs included in the examined coursebooks were not selected based on their frequency of use by NS of English. These results are consistent with the findings of some of the previous studies in the field (Hanzén, 2007; Vanyushkina-Holt, 2005), which also found that the proverbs included in the coursebooks were not among the well-known/ frequently used proverbs in present-day English. Mieder (2004) argues that proverbs which are in use today should be taught, especially considering the time constraint on language learning. Both teachers and coursebook writers need to be selective when incorporating proverbs in language teaching. The incorporation of the most familiar and frequently used proverbs should pave the way for effective and efficient teaching.

Conclusion and Implications

Our aim with this study was threefold: (i) to show how proverbs could contribute to the development of the learners' CC as defined by Bachman (1990); (ii) to identify the competencies that proverbs in the coursebooks could develop; (iii) to uncover whether the proverbs in the coursebooks were among the most known/frequently used proverbs in present-day English.

Scrutiny of the available literature shows that "proverbs can be an umbrella" under which any number of language teaching objectives may be accomplished (Holden & Warshaw, 1985:63). If they are combined with the appropriate technique, proverbs may be used to develop learners' GrC, TextC, IllocC, and SoclC. Incorporating proverbs in language classes can widen students' perspec-

tives of the world and can enable them to understand both their own and foreign cultures better, since proverbs are the devices that "unite speakers, speakers to their communities, and communities to ideas of universal 'truth' in human experience" (Gibbs, 2001:167).

The findings of this study underline once again that coursebooks are "the visible heart of any ELT program" (Sheldon, 1988:237) and that their content should be considered carefully. An overwhelming majority of our participants reported that they were exposed to English mainly in the classroom where, as in other EFL contexts, the coursebooks (Sinclair & Renouf, 1988; Swe, 2017; Tsagari & Sifakis, 2014) were the main/sole teaching materials. Therefore, coursebooks (especially in EFL contexts) are essential means for teaching proverbs in a way that can contribute to the development of learners' CC. Unfortunately, many of the coursebooks examined in this study included only a limited number of proverbs and these did not support the development of all of the competences in BMCC. Among the four sub-competencies specified by Bachman (1990), GrC (vocabulary, grammar, phonology) and SoclC (interpreting cultural references) were the better supported ones. TextC and IllocC, on the other hand, were rarely dealt with or totally neglected, which in our opinion, was a valuable opportunity squandered. Our suggestion, therefore, is that writers of learning material should start by scrutinising studies on formal, semantic, cultural, literary, and pragmatic features of proverbs and try to incorporate the results of their research more effectively in language coursebooks by means of various communicative tasks. The form and meaning of proverbs should be accompanied by their functions and cultural and figurative background, which are, according to De Caro (1978), the required parts of the proverb competence. NS who acquire proverb competence at an early age not only know which individual proverbs exist, but also know what they mean in their culture and how they are used in communication (De Caro, 1978).

Examination of the coursebooks also showed that most of the proverbs were not among the well-known/frequently used ones by NS of English. This finding confirms Tomlinson's claim (2003:72) that there is a "wide mismatch between … research findings and actual practice in many coursebooks and published materials." The findings also support Koprowski (2005) and Ur (1996) who argue that sometimes coursebooks fail to present appropriate and realistic language models, fostering cultural understanding and addressing discourse competence. Many of the teaching materials examined for this study exposed students to proverbs with limited usefulness and no real-life language use. With regard to specifying useful multi-word lexical phrases for inclusion in the coursebooks, Koprowski (2005:331) also asserts that "writers and publishers may need to reassess their priorities and avoid careless, convenient, or arbitrary specification."

Many proverbs exist in English (Norrick, 1985) but space in coursebooks allocated to such proverbs is limited. Therefore, it is coursebook writers' professional and pedagogical responsibility to "minimize or eradicate the inclusion of questionably useful" (Koprowski, 2005:328) expressions in those materials. The selection of proverbs to be included in the coursebooks should be principled, careful, and based on either empirically composed lists or corpora. Close collaboration should also exist between researchers, coursebooks writers, administrators, teachers, and students.

It is hoped that this study will serve as a guide for material writers, publishers, administrators selecting teaching materials, and teachers whose aim is to create and choose materials with high pedagogical value. Studying proverbs may not solve all of the problems in language teaching classes but it may provide some answers for important questions (Holden & Warshaw, 1985). After all, a good beginning makes a good ending.

Authors' Contribution

This article is the outcome of the two authors' combined work. Each author was responsible for 50 percent of the outcome.

Notes

i .In this article the terms "students" and "learners" are used interchangeably and they mean "native speakers of Turkish learning English."

ii.Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abu-Talib M 1982. Proverbs in the classroom. In A Benhallam (ed). Proceedings 2nd Spring Conference of MATE. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.134.1581&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed October 2017. [ Links ]

Alexander RJ 1984. Fixed expressions in English: Reference books and the teacher. ELT Journal, 38(2):127-134. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/38.2.127 [ Links ]

Allen C 2015. Marriages of convenience? Teachers and coursebooks in the digital age. ELT Journal, 69(3):249-263. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv005 [ Links ]

Amuseghan SA & Olayinka AL 2007. An evaluation of intensive English (Book I) as a coursebook for English as second language in Nigeria. Nebula, 4(3):179-201. Available at https://cdn.atria.nl/ezines/web/Nebula/2008/5.1-5.2/nobleworld/A_and_O.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Arikan A & Tekir S 2007. An analysis of English language teaching coursebooks by Turkish writers: "Let's speak English 7" example. International Journal of Human Sciences, 4(2):1-18. Available at https://j-humansciences.com/ojs/index.php/IJHS/article/view/321/223. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Babiker GIS 2017. Using translated Sudanese proverbs in ELT at tertiary level (A case study of the Faculty of Arts-University of Kordofan). PhD dissertation. Al-Ubayyid, Sudan: University of Kordofan. [ Links ]

Bachman LF 1990. Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Batdı V & EladıŞ 2016. Analysis of high school English curriculum materials through Rasch measurement model and Maxqda. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri [Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice], 16(4):1325-1347. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2016.4.0290 [ Links ]

Bessmertnyi A 1994. Teaching cultural literacy to foreign-language students. English Teaching Forum, 32(4):24-27. [ Links ]

Botha E 2009. Why metaphor matters in education. South African Journal of Education, 29(4):431-444. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n4a287 [ Links ]

Byram M, Gribkova B & Starkey H 2002. Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg, France: Language Policy Division, Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education, Council of Europe. Available at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1562524/1/Starkey_InterculturalDimensionByram.pdf. Accessed 10 January 2020. [ Links ]

Byrd DR, Cummings Hlas A, Watzke J & Montes Valencia MF 2011. An examination of culture knowledge: A study of L2 teachers' and teacher educators' beliefs and practices. Foreign Language Annals, 44(1):4-39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01117.x [ Links ]

Çakir A 2016. Raising awareness on the Turkish learners of English about the arbitrary nature of figurative expressions. European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(2):248-252. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejms.v1i2.p248-252 [ Links ]

Çakir İ 2006. Socio-pragmatic problems in foreign language teaching. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 2(2):136-146. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/104652. Accessed 26 April 2017. [ Links ]

Çakir İ 2010. The frequency of culture-specific elements in the ELT coursebooks at elementary schools in Turkey. Novitas-ROYAL, 4(2):182-189. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED552914.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2017. [ Links ]

Campillo PS 2008. Examining mitigation in requests: A focus on transcripts in ELT coursebooks. In EA Soler & S Jordà (eds). Intercultural language use and language learning. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Can N 2011. A proverb learned is a proverb earned: Future English teachers' experiences of learning English proverbs in Anatolian Teacher Training High Schools in Turkey. MA thesis. Ankara, Turkey: Middle East Technical University. Available at https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12613381/index.pdf. Accessed 24 February 2020. [ Links ]

Can Daşkın N 2011. Killing two birds with one stone: Proverbs and intercultural communicative competence. In S Ağıldere & N Ceviz (eds). Proceedings of the 10th International Language, Literature and Stylistics Symposium. Ankara, Turkey: Bizim Büro. [ Links ]

Can Daşkın N & Hatipoğlu Ç 2019. A proverb learned is a proverb earned: Proverb instruction in EFL classrooms. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(1):57-88. https://doi.org/10.32601/ejal.543781 [ Links ]

Ciccarelli A 1996. Teaching culture through language: Suggestions for the Italian language class. Italica, 73(4):563-576. https://doi.org/10.2307/479507 [ Links ]

Cooper TC 1999. Processing of idioms by L2 learners of English. TESOL Quarterly, 33(2):233-262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587719 [ Links ]

Corbett J 2003. An intercultural approach to English language teaching. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

Cunningsworth A 1995. Choosing your coursebook. Oxford, England: Heinemann. [ Links ]

D'Angelo FJ 1977. Some uses of proverbs. College Composition and Communication, 28(4):365-369. https://doi.org/10.2307/356733 [ Links ]

De Caro FA 1978. Proverbs and originality in modern short fiction. Western Folklore, 37(1):30-38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1499135 [ Links ]

Drew P & Holt E 1998. Figures of speech: Figurative expressions and the management of topic transition in conversation. Language in Society, 27(4):495-522. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500020200 [ Links ]

Dundes A 1975. On the structure of the proverb. Proverbium, 25:961-973. [ Links ]

Ellis NC 2008. Phraseology: The periphery and the heart of language. In F Meunier & S Granger (eds). Phraseology in foreign language learning and teaching. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht A 2008. The impact of role reversal in representational practices in history textbooks after Apartheid. South African Journal of Education, 28(4):519-541. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/191/130. Accessed 1 January 2020. [ Links ]

Friesen P 1978. The use of oral tradition in the novels of Conrad Richter. PhD dissertation. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University. [ Links ]

Gibbs RW Jr 2001. Proverbial themes we live by. Poetics, 29(3):167-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(01)00041-9 [ Links ]

Giddy P 2012. "Philosophy for children" in Africa: Developing a framework. South African Journal of Education, 32(1):15-25. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n1a554 [ Links ]

Göçmen E, Göçmen N & Ünsal A 2012. The role of idiomatic expressions in teaching languages and cultures as part of a multilingual approach. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55:239-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.500 [ Links ]

Gözpınar H 2014. Activities to promote the use of proverbs to develop foreign language skills. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM), 4(4):107-111. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594330.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2020. [ Links ]

Haas HA 2008. Proverb familiarity in the United States: Cross-regional comparisons of the paremiological minimum. Journal of American Folklore, 121(481):319-347. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaf.0.0020 [ Links ]

Hallin AE & Van Lancker Sidtis D 2017. A closer look at formulaic language: Prosodic characteristics of Swedish proverbs. Applied Linguistics, 38(1):68-89. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu078 [ Links ]

Hanzén M 2007. "When in Rome, do as the Romans do": Proverbs as a part of EFL teaching. Bachelor degree thesis. Jönköping, Sweden: Jönköping University. Available at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:3499/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 30 December 2019. [ Links ]

Harnish RM 1993. Communicating with proverbs. Communication and Cognition, 26(3-4):265-290. [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2009. Do we speak the same culture?: Evidence from students in the foreign language education departments. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Comparative Literature and the Teaching of Literature and Language: We Speak the Same Culture (Vol. 29). Ankara, Turkey: Gazi University. [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2010. Summative evolution of an English language testing and evaluation course for future English language teachers in Turkey. English Language Teacher Education and Development (ELTED), 13:40-51. Available at http://www.elted.net/uploads/7/3/1/6/7316005/v13_5hatipoglu.pdf. Accessed 30 December 2019. [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2012. British culture in the eyes of future English language teachers in Turkey. In Y Bayyurt & Y Bektaş-Çetinkaya (eds). Research perspectives on teaching and learning English in Turkey: Policies and practices. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2013. ODTÜ Türkçe İngilizce Sınav Derleminin Oluşturulmasındaki İlk Aşamalar (METU TEEC) [First stage in the construction of METU Turkish English Exam Corpus (METU TEEC)]. Boğaziçi University Journal of Education, 30(1):1-19. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/43799. Accessed 15 January 2018. [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2016. The impact of the University Entrance Exam on EFL education in Turkey: Pre-service English language teachers' perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 232:136-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.038 [ Links ]

Hatipoğlu Ç 2017. Linguistics courses in pre-service foreign language teacher training programs and knowledge about language. ELT Research Journal, 6(1):45-68. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/296293. Accessed 20 December 2017. [ Links ]

Hendon US 1980. Introducing culture in the high school foreign language class. Foreign Language Annals, 13(3):191-199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1980.tb00751.x [ Links ]

Hirsch ED Jr, Kett JF & Trefil J 2002. The new dictionary of cultural literacy. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Holden MH & Warshaw M 1985. A bird in the hand and a bird in the bush: Using proverbs to teach skills and comprehension. The English Journal, 74(2):63-67. https://doi.org/10.2307/816272 [ Links ]

Hornby AS (ed.) 2000. Oxford advanced learner's dictionary of current English (6th ed). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Irujo S 1986. Don't put your leg in your mouth: Transfer in the acquisition of idioms in a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 20(2):287-304. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586545 [ Links ]

Jafarigohar M & Ghaderi E 2013. Evaluation of two popular EFL coursebooks. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 2(6):194-201. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.2n.6p.194 [ Links ]

Kayapinar U 2009. Coursebook evaluation by English teachers. Inonu University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 10(1):69-78. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/92310. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Khan Ö & Can Daşkin N 2014. "You reap what you sow": Idioms in materials designed by EFL teacher-trainees. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language, 8(2):97-118. Available at http://www.novitasroyal.org/Vol_8_2/khan_can-daskin.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019. [ Links ]

Koprowski M 2005. Investigating the usefulness of lexical phrases in contemporary coursebooks. ELT Journal, 59(4):322-332. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci061 [ Links ]

Kuimova MV, Uzunboylu H & Golousenko MA 2017. Foreign language learning in promoting students' spiritual and moral values. Ponte, 73(4):263-267. https://doi.org/10.21506/j.ponte.2017.4.56 [ Links ]

Lakoff G & Turner M 1989. More than cool reason: A field guide to poetic metaphor. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Lázár I 2003. Présentation de mirrors and windows: Un manuel de communication interculturelle [Introducing mirrors and windows: An intercultural communication textbook]. In I Lázár (ed). Intégrer la competence en communication interculturelle dans la formation des enseignants [Incorporating intercultural communicative competence in language teacher education]. Bachernegg, Kapfenberg: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Lenskaya E 2013. The price of standardized testing in Russia. Available at http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/international_perspectives/2013/10/the_price_of_standardized_testing_in_russia.html. Accessed 15 October 2017. [ Links ]

Liontas JI 2002. Exploring second language learners' notions of idiomaticity. System, 30(3):289-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00016-7 [ Links ]

Litovkina AT 2000. A proverb a day keeps boredom away. Pécs-Szekszárd: IPF-Könyvek. [ Links ]

Litovkina AT, Mieder W & Földes C 2006. Old proverbs never die, they just diversify: A collection of anti-proverbs. Veszprém, Hungary: Pannonian University of Vesprém. [ Links ]

Littlemore J & Low GD 2006a. Figurative thinking and foreign language learning. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Littlemore J & Low G 2006b. Metaphoric competence, second language learning, and communicative language ability. Applied Linguistics, 27(2):268-294. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/aml004 [ Links ]

Loumbourdi L 2014. The power and impact of standardised tests: Investigating the washback of language exams in Greece. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang GmbH. [ Links ]

Mieder W 1993. Proverbs are never out of season: Popular wisdom in the modern age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mieder W 2004. Proverbs: A handbook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Mieder W & Holmes D 2000. Children and proverbs speak the truth: Teaching proverbial wisdom to fourth graders. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers. [ Links ]

Milner GB 1971. The quartered shield: Outline of a semantic taxonomy. In E Ardener (ed). Social anthropology and language. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nnolim CE 1983. The form and function of the folk tradition in Achebe's novels. ARIEL, 14(1):35-47. Available at https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ariel/article/viewFile/32643/26695. Accessed 20 May 2017. [ Links ]

Norrick NR 1985. How proverbs mean: Semantic studies in English proverbs. Berlin, Germany: Mouton. [ Links ]

Norrick NR 2007. Proverbs as set phrases. In H Burger, D Dobrovol'skij, P Kühn & NR Norrick (eds). Phraselogie: Ein internationales handbuch der zeitgenössischen forschung [Phraseology: An international handbook of contemporary research] (Vol. 1). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Nuessel F 2003. Proverbs and metaphoric language in second-language acquisition. In W Mieder (ed). Cognition, comprehension and communication: A decade of North American proverb studies (1990-2000). Baltmannsweiler, Germany: Schneider-Verlag Hohengehren. [ Links ]

Obeng SG 1996. The proverb as a mitigating and politeness strategy in Akan discourse. Anthropological Linguistics, 38(3):521-546. [ Links ]

Ohia IN & Adeosun N 2002. ELS coursebooks and self-instruction: A pedagogical evaluation. In A Lawal, I Isiugo-Abanihe, IN Ohia & E Ubahakwe (eds). Perspectives on applied linguistics in language and literature. Ibadan, Nigeria: Stirling-Horden. [ Links ]

O'Keeffe A, McCarthy M & Carter R 2007. From corpus to classroom: Language use and language teaching. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ötügen R 2016. Ingilizce siniflarinda öğretmen tarafindan hazirlanan materyaller: Öğretmen ve öğrenci görüşleri [Teacher-made materials in ELT classes: Teachers' and students' views]. Atatürk Üniversitesi Kazım Karabekir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 33:23-34. Available at https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/266118. Accessed 13 December 2019. [ Links ]

Porto M 1998. Lexical phrases and language teaching. Forum, 36(3). [ Links ]

Prodromou L 2003. Idiomaticity and the non-native speaker. English Today, 19(2):42-48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078403002086 [ Links ]

Richmond EB 1987. Utilizing proverbs as a focal point to cultural awareness and communicative competence: Illustrations from Africa. Foreign Language Annals, 20(3):213-216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1987.tb02947.x [ Links ]

Ridout R & Witting C 1969. English proverbs explained. London, England: Pan Books. [ Links ]

Rowland D 1926. The use of proverbs in beginners' classes in the modern languages. The Modern Language Journal, 11(2):89-91. https://doi.org/10.2307/314127 [ Links ]

Sackstein, S, Spark L & Jenkins A 2015. Are e-books effective tools for learning? Reading speed and comprehension: iPad® vs. paper. South African Journal of Education, 35(4):Art. # 1202, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n4a1202 [ Links ]

Sadeghi K & Richards JC 2015. Teaching spoken English in Iran's private language schools: Issues and options. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 14(2):210-234. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-03-2015-0019 [ Links ]

Searle JR 1975. Indirect speech acts. In P Cole & JL Morgan (eds). Syntax and semantics (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Sheldon LE 1988. Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials. ELT Journal, 42(4):237-246. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.237 [ Links ]

Simpson JA & Speake J (eds.) 2003. Oxford concise dictionary of proverbs. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sinclair J 1992. Shared knowledge. In Proceedings of the Georgetown University roundtable in linguistics and pedagogy: The state of the art. Georgetown, NW: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Sinclair J McH & Renouf A 1988. A lexical syllabus for language learning. In R Carter & M McCarthy (eds). Vocabulary and language teaching. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Steen G 2014. The cognitive-linguistic revolution in metaphor studies. In JR Taylor & J Littlemore (eds). The Bloomsbury companion to cognitive linguistics. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Swe ST 2017. Teachers' use of authentic materials for teaching cultural elements lessons through coursebooks in EFL classrooms. In A Maley & B Tomlison (eds). Authenticity in materials development for language learning. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Tomlinson B (ed.) 2003. Developing materials for language teaching. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Tsagari D & Sifakis NC 2014. EFL course book evaluation in Greek primary schools: Views from teachers and authors. System, 45:211-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.04.001 [ Links ]

Turkol S 2003. Proverb familiarity and interpretation in advanced non-native speakers of English. M.S. thesis. New Haven, CT: Southern Connecticut State University. [ Links ]

Ulusoy Aranyosi E 2010. "Atasözü" neydi, ne oldu? [What was, and what now is, a "proverb"]. Milli Folklor, 22(88):5-15. Available at http://www.millifolklor.com/PdfViewer.aspx?Sayi=88&Sayfa=2. Accessed 12 September 2017. [ Links ]

Ur P 1996. A course in language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Vanyushkina-Holt N 2005. Proverbial language and its role in acquiring a second language and culture. PhD dissertation. Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College. [ Links ]

Wall D & Horák T 2011. The impact of changes in the TOEFL® exam on teaching in a sample of countries in Europe: Phase 3, the role of the coursebook Phase 4, describing change. ETS Research Report Series, 2011(2):i-181. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2011.tb02277.x [ Links ]

Weigle SC 2013. English as a second language writing and automated essay evaluation. In MD Shermis & J Burstein (eds). Handbook of automated essay evaluation: Current applications and new directions. Oxford, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wray A 2000. Formulaic sequences in second language teaching: Principle and practice. Applied Linguistics, 21(4):463-489. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.4.463 [ Links ]

Yano Y 1998. Underlying metaphoric conceptualization of learning and intercultural communication. Intercultural Communication Studies, 7(2):129-136. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.602.4108&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 25 September 2017. [ Links ]

Yorio CA 1980. Conventionalized language forms and the development of communicative competence. TESOL Quarterly, 14(4):433-442. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586232 [ Links ]

Yurtbaşı M n.d. How to learn English through proverbs. Istanbul, Turkey: Arion. [ Links ]

Received: 13 February 2018

Revised: 1 April 2019

Accepted: 14 June 2019

Published: 29 February 2020

Appendix C: The Analysis Form Used for Coursebook Analysis (Adapted from Can, 2011)