Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1738

ARTICLES

The effect of psychological violence on preschool teachers' perceptions of their performance

Zeynep ÇetinI; Miray Özözen DanacýII; Abdullah KuzuIII

IDepartment of Child Development, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey zcetin@hacettepe.edu.tr

IIDepartment of Early Childhood Education, Izmir Democracy University, Izmir, Turkey

IIIEmeritus Professor, Department of Educational Sciences Instructional Technologies, Faculty of Education, Izmir Democracy University, Izmir, Turkey

ABSTRACT

The phenomenon of psychological violence (mobbing) explained within the context of psychological aggression, is gaining attention due to increased focus on industrialisation and work life. The study aimed to examine the effects of mobbing experienced by teachers on the way they perceive their performance. The research sample consisted of 698 teachers (647 female/51 male) working in public preschools. The Mobbing Scale developed by Yaman (2009), and the Teachers' Perception of Performance Scale developed by Özözen Danacý (2009) were used as data collection tools. In data analysis, the correlations of teachers' psychological violence levels to their self-performance assessment and managing skills were determined. The findings suggest that there is a significant negative relationship between psychological violence and work performance. Based on the findings obtained in this study, the aim was to establish an educational environment without any psychological violence to provide an improved service.

Keywords: classroom; performance; preschool; primary education; psychological violence (mobbing); teacher

Introduction

In an ever-changing world, educational institutions play a significant role in realising social objectives and finding the best solutions for the systems within the society. Therefore, educational institutions should have the power and outfit to overcome obstacles. The progressive increase in the demand for a skilled labour force, proper functioning of healthy educational institutions, the quality of superior-subordinate relationships, and the existence of stress and conflicts are important issues that influence the establishment of an institutional culture. Factors such as competition, transformation, and different views within educational institutions play significant roles in the emergence of psychological violence or mobbing. Mobbing is a world-wide problem in many universities, as is in modern workplaces. Strict hierarchy, administrators' authoritarianism, academic jealousy, hostile attitudes from students, a lack of job security, and working in the same department for a long time may be regarded as main organisational factors of mobbing (Cogenli & Asunakutlu, 2016; Garthus-Niegel, Nübling, Letzel, Hegewald, Wagner, Wild, Blettner, Zwiener, Latza, Jankowiak, Liebers & Seidler, 2016.)

Currently, people spend a significant amount of time at their workplaces. Conflict and differences of opinion are experienced in all institutions, but these differences and conflicts may progress to become bullying, tiring, humiliating, or even physically and psychologically damaging issues (Yaman, 2009). Of these issues, psychological and social problems are the most significant. Psychological abuse or emotional pressure is one such problem, and bullying (by one or more people against another person) is applied cognitively or systematically through hostile and unethical methods (Leymann & Gustafsson, 1996).

Psychological violence is psychological terror, emotional attack, physical attack, or threatening behaviour. Konrad Lorenz first referred to mobbing in the 1970s for defining the joint attacks of small groups of animals on a big animal to defend themselves; after twenty years, mobbing has become a popular subject in Europe and beyond (Tutar, 2004).

Psychological violence (mobbing) has negative impacts on organisations and organisational culture and may cause many negative outcomes in individuals. The job performance of an individual exposed to psychological violence in the workplace is negatively affected. The initial psychological effects of mobbing are an unwillingness to go to work, exhaustion, loss of concentration, and frustration, where these lead to a decline in job performance. Chronic tension, stress, and conflicts decrease an individual's creativity, innovative thinking skills, productivity, and motivation, which are collectively termed as a decrease in performance.

Economic effects of mobbing include an increase in psychological and physical health expenses, and income losses due to being unemployed (Tinaz, 2006). Moreover, mobbing causes million-dollar damages due to the increase in the turnover of experienced, well-performing staff, a decrease in productivity and performance, and a decrease in work quality (Hoel, Rayner & Cooper, 1999). The social effects of mobbing may include damage to professional reputation and the victim being perceived as unsuccessful. Psychological and physical effects of mobbing on victims include depression, fear, tachycardia, distraction, aches, gastrointestinal disorders, feeling of desolation, loss of appetite, unintentional weight loss, loss of self-confidence and self-esteem, and post-traumatic stress disorder, in more serious cases (Bayrak, 2007; Tinaz, 2006).

Violence at Work, published by the International Labour Organization ([ILO], n.d.), states that although psychological violence is considered harmless, it is included on the same list as bullying, murder, rape, or robbery (Davenport, 1999). Hornstein (1996) and Pillay (2016) estimate that as many as 23 million Americans face workplace abuse daily, which is close to epidemic proportions. This shows the extent of psychological violence.

Mobbing disrupts the physical, mental, social, and economic well-being of academics and workers in other spheres, and obstructs effective scientific activities. In addition, mobbing reduces job satisfaction and causes unemployment (Vartia-Väänänen, 2003).

Literature Review

Davenport, Schwartz and Elliott (2002) put forth that studies indicate that psychological violence is more prevalent in non-profit organisations, schools and health sectors, which decreases work efficiency in these sectors. Communication/interaction between the members of educational and other institutions, and perceptions on these relations have significant effects on institutional productivity and performance levels, of which a decline in the quality and quantity of work due to bullying behaviour at work is the most prevalent (Canitez-Okur, 2007; Pillay, 2016; Yaman, 2009).

Although the exact cost of productivity loss and negative social effects caused by psychological violence in health, psychology, and legal systems cannot be defined, performance decline is believed to result in the loss of millions of dollars (Aquino & Byron, 2002; Davenport, 1999).

Performance can be defined as the action or process of performing a task or function, or as an employee behaviour pattern. To ensure success in a job, the job to be performed by an employee should be defined, the standards required by the job should be specified, and compliance of the employee's qualifications to these standards should be examined. Thus, performance and success are closely connected concepts (Akcakaya, 2012; Armstrong, 1996; Aydin, 2009; Helvaci, 2002).

On an educational basis, teachers' assessment before and after their education indicate the efficiency of the educational programme. Evaluating the performance of teachers is not an activity exclusive to experts, supervisors or principals. The realistic face of the performance assessment is the teachers' self-assessments, as they assess their own performances (Helvaci, 2002).

Since performance is important, it is necessary to define the psychological effects that reduce any performance that may affect it.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

Teacher assessment studies demonstrate that instead of increasing the pressure on teachers, teachers' energy should be directed toward more fundamental issues rather than superficial and unusual acts. Therefore, the main objectives of assessing teachers' performance are to inform them about their current performance, develop their professional competence, assist in individual improvement and institutional development, increase in individual productivity and motivation, and develop institutional productivity and loyalty (Brown, 2005; Mathias, Mertin & Murray, 1995).

Teacher motivation is an essential factor for student motivation in the classroom and advanced level education reforms. The competencies of early childhood education teachers, including their attitudes, knowledge, and skills, are important for the progress and development of the institution to reach its main objectives (Henniger, 1999; Kulpcu, 2009; Sheridan & Rice, 1991).

This research was conducted to define the possible relationship between exposure to psychological violence and work performance. The effects of psychological violence on performance and occupational satisfaction of the preschool and classroom teachers exposed to mobbing were examined for various variables.

Methodology

Research Model

A relational survey model, a type of general survey model, was used in this study because it was suitable for the topic and objectives. The relational survey model is a research model aimed at determining the presence and/or the degree of changes in two or more variables (Karasar, 2004). The research was designed as a survey model using the random sampling method.

Research Universe

The research study group consisted of preschool and classroom teachers working in primary schools, which included preschools affiliated to the Ministry of Education in the central districts of Sakarya and Kocaeli, and the city of Duzce in Turkey. This sample group was chosen for its ease of access.

Sample

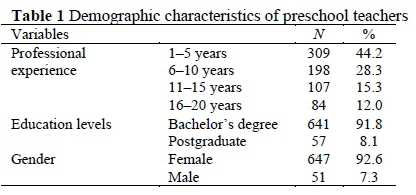

The research sample consisted of 698 teachers, of which 352 teachers were from 20 preschools in the central district of Duzce, 265 preschool teachers were from 25 preschools in the central district of Sakarya, and 81 teachers were from preschools in the central district of Kocaeli. Different numbers of teachers from each educational institution were selected to constitute the study group. All 698 preschool teachers completed the data forms properly. As the majority of primary teachers in Turkey are female, 647 of the sample were female while only 51 were male. Frequencies and percentages of the distribution of teachers for demographic variables are presented in Table 1.

Data Collection Tools

The questionnaire, used as the data collection tool, comprised of three sections. The first section was for recording of the teachers' personal information. The second section included a mobbing scale consisting of 23 items, and the third section included the Teachers' Perception of Performance Scale consisting of 26 items.

The data was collected on a voluntary basis and permission for the research was granted by the national ministry of education.

Personal information form

The researchers prepared the personal information form to obtain socio-demographic information from the participants. This form included questions about the teachers' gender, professional experience, and education level.

Mobbing scale

The Psychological Violence-Mobbing Scale developed by Yaman (2009) was used to measure psychological violence. Yaman's (2009) scale was found reliable and valid in a study on reliability and validity of scales and is widely used to measure psychological violence in scientific studies. The factor load of the scale differs between .77 and .91. The reliability coefficients for internal consistency are as follows: .91 for humiliation, .77 for discrimination, .79 for sexual harassment, and .79 for communicative obstacles. The test-retest reliability coefficients are .91 for humiliation, .78 for discrimination, .82 for sexual harassment, and .82 for communicative obstacles. Item analyses show that the item-total score correlations of the subscales vary between .54 and .78. The mobbing scale can thus be regarded as a valid and reliable instrument to be used.

Teachers' perception of performance scales

The scale developed by Özözen Danacý (2009) for teacher performance management is a five-point Likert-type scale with 26 items. The minimum score is 1, and the maximum score is 4 on the scale. According to the analysis results, the scale was demonstrated for use as a one-factor scale after removing the item with the lowest factor-load (the interruption of classes, for example, outside announcements or students being called out of class). In the reliability and validity studies of the scale conducted by Özözen Danacý (2009), the factor load values of the items in the scale range between .42 and .85. Total variance explained by the factors is 86.43%, and the Cronbach's Alpha reliability coefficient is α = .89.

Data Analysis Techniques

SPSS 17.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software was used for data analysis. In the data analysis standard deviation, arithmetic mean, frequency, and percentages from descriptive statistics were used. Moreover, t-test, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), regression analysis, the non-parametric Mann Whitney U test, and the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis H test were used to determine statistical significance.

A simple correlation analysis was done to determine the level (degree-volume-strength) and direction of the relation between psychological violence that teachers are exposed to and teachers' performance perceptions. As the data form was not completed properly for four participants, these were not analysed.

Results/Findings

This section includes the research findings based on the research problem.

Descriptive Statistics Results of Teachers on Both Scales

It was observed in Table 2 that teachers mainly chose "Sometimes" to respond to questions (X̅ = 2.29).

The two items that yielded the highest number of responses were, "I use the most proper teaching methods and techniques for the development and readiness levels of students" (X̅= 4.04), and "I establish connections with the prior knowledge of students in the learning process" (X̅= 4.19). The two items to which the participants responded with "Never" were "I produce or participate in new projects to increase the quality of education" (X̅= 1.23), and "I collaborate with people, institutions and organizations to increase the quality of education" (X̅= 1.44). These analyses indicate that teachers do not perform practices focusing on the external stakeholders much.

According to Table 3, regarding being exposed to psychological violence, 47.1% of the participants (328 teachers) selected the item "The institution does not provide an atmosphere available for a healthy communication with my colleagues". Forty-nine percent of participants (342 teachers) selected "Legal rights of teachers are not provided in the workplace," 27% (188 teachers) highlighted that "teachers are excluded from the group and isolated," and 26% (181 teachers) stressed, "some gossips turning around on them."

Teachers' Levels of Exposure to Mobbing according to their Demographics

Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations of the psychological violence level for teachers according to gender. When the teachers' views on determining psychological violence levels to which they were exposed were analysed, a significant difference for gender was observed [t(2.671)= -308; p < 0.04]. The data indicates that male teachers were less exposed to psychological violence compared to female teachers.

Table 4 indicates the gender differentiation, if any, for the sub-dimensions of psychological violence to which teachers were exposed, and significant differences for the sub-dimensions of humiliation and discrimination were observed. The study results suggest that women were exposed to more humiliation and discrimination than men. No significant differences in terms of gender were found for the sub-dimensions of sexual harassment and communication obstacles.

Table 5 indicates whether the teachers' levels of exposure to mobbing differed according to their education level, and a significant difference was found (U = 1376.4; p > 0.04). This indicated that teachers with postgraduate degrees were exposed to more psychological violence than teachers with bachelor's degrees.=

Table 6 presents the mean scores of the teachers' exposure to mobbing when professional experience is taken into account. When the data was analysed, a significant difference was observed between the teachers' views on the exposure to mobbing regarding professional experience. Dunnett's C test was conducted to define the groups among which this difference was statistically significant, and statistically significant differences [f (8.348) = 2.561; p < 0.04] were found between teachers with six to ten years' professional experience and teachers with sixteen to twenty years' experience. The arithmetic mean scores indicate that teachers with six to ten years' experience reported the highest perception level for exposure to mobbing. This group was followed by teachers with one to five years' experience (X̅= 2.265), eleven to fifteen years' experience (X̅ = 2.106), and sixteen to twenty years' experience (X̅ = 2.069) respectively. The average psychological violence level for years of professional experience was determined as (X̅ = 2.169).

The Relationship between the Level of Mobbing Experienced by Teachers and Their Performance Perceptions

A Pearson correlation analysis was done to determine the level (degree-volume-strength) and direction of the relation between the psychological violence perpetrated on teachers and their performance perception. The results are presented in Table 7.

There is a moderately significant, negative relationship between the teachers' views on mobbing experienced and their performance perceptions (r =-.501; p < 0.05).

The study results indicate that an increase in the exposure to mobbing among preschool and classroom teachers in the educational institutions led to a significant decline in the perceptions of their performance. Therefore, it can be stated that the educational institutions where teachers were exposed to psychological violence showed a high probability of decline in teachers' performance levels.

Correlation Analysis Results for the Relationship Between Teachers' Level of Exposure to Mobbing and Their Level of Performance Perceptions by Demographic Characteristics

Correlation analysis results for the relationship between teachers' level of exposure to mobbing and their performance perceptions regarding education level and gender variables, are discussed in this section.

Table 8 indicates the relationship between the teachers' levels of exposure to mobbing and their performance perceptions, and how, if at all, these differed by education level. The data suggests that there was a moderate negative linear correlation for the difference between the scores of performance perceptions of teachers and their views on psychological violence by education level.

Table 9 shows the relationship between the teachers' levels of exposure to mobbing and their performance perceptions by gender. The data suggests that there is a moderate negative linear correlation for the difference between the scores of performance perceptions of teachers and their views on psychological violence by gender.

Discussion

The consequences of psychological violence are not only limited to individuals, but can also affect business institutions, and thus the economy and the country. Therefore, the results of the study are important for influencing countries' economic situations, employee performance, and productivity.

Study findings suggest that there is a significant relation between psychological violence in educational institutions and the performance of teachers. There is a negatively significant relationship between the effect of psychological violence on preschool and classroom teachers in primary education institutions and their performance. A significant decrease in the work performance of teachers was found in educational institutions where teachers were exposed to psychological violence.

Blase and Blase (2003) indicate that two-thirds of teachers receive psychological counselling. Demirel (2009) and Ravisy (2000), indicate that the most significant effects of psychological violence on teachers include loss of time, loss of team spirit, unwillingness to work, lack of concentration, unwillingness to give lectures, occupational burnout, loss of desire to learn and conduct research, occupational failure, avoiding occupational activities, and being less productive. Moreover, studies (Branch, Sheehan, Barker & Ramsay, 2004; Ege, 1999; Sheehan, Barker & Rayner, 1999) show that mobbers inflict psychological violence and rob workers of a healthy and efficient work environment, preventing the success of hardworking and talented employees. Kilic (2007) defines this fact as mobbers pose as hardworking and essential parts of their organization, however, mobbers regard the success of other employees in the organisation a major drawback.

Tutar (2004) states that mobbers with narcissist personality disorder exhibit antipathetic, narcissist, egocentric and jealous mobbing behaviour, which is explained by the social skill deficiency model and Machiavellianism (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Menesini, Sanchez, Fonzi, Ortega, Costabile & Lo Feudo, 2003). Zapf (1999) states that victims of mobbing are honest, hardworking, self-confident, and trustworthy people. Thus, the characteristic definitions of the mobber and the victim can be directly related to the concept of mobbing and the concepts of diligence and efficient individuality.

Bandow and Hunter (2008) state that the workplace environment and workplace civility/incivility are the two important factors affecting employee motivation and productivity. Successful, creative, honest, and promising individuals are more exposed to psychological violence, indicating that high-performance individuals are the targets of mobbers who rob them of self-motivation. Bullies inflict psychological violence on individuals whose performance levels are, or may be, high, resulting in a decrease in their work performance and productivity. Although the exact cost of productivity loss and negative social effects caused by psychological violence in health, psychology, and the legal system cannot be defined, it is estimated to cost millions of dollars (Aquino & Byron, 2002; Davenport, 1999). Many studies emphasise that unethical behaviour is damaging to the future of organisations as such behaviour negatively affects communication and loyalty within the organisation, increases the turnover rate, results in a decline of self-respect, and decreases motivation (Ozkalp & Kirel, 2001). Moreover, Kilic (2007) and Lodge (2001) underline the significant relationship between psychological violence and performance, and state that in the first phase of psychological violence, no significant effect is observed on the victim, but a significant decline in performance is observed in the subsequent phases.

The analysis of data for the demographic characteristics demonstrates significant relationships between being exposed to psychological violence and teachers' gender, occupational experience, or educational levels.

Inter-gender correlation was evaluated and it was found that female teachers were more exposed to psychological violence compared to male teachers. Moreover, teachers with less professional experience were more exposed to mobbing than teachers with more professional experience, and teachers holding postgraduate degrees were more exposed to psychological violence compared to teachers with bachelor's degrees. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the dimensions of humiliation and discrimination between female and male teachers. There were no significant differences in the dimensions of sexual harassment and communication obstacles of psychological violence between female and male teachers.

Other studies on psychological violence suggest that men are four times more likely to engage in physical aggression than women. Women usually apply indirect psychological violence on their victims, such as gossiping and spreading false rumours; compared to men, women are more likely to develop depression (Bowmen, Stevens, Eagle & Matzopoulos, 2014; Fineman, Gabriel & Sims, 2010; Mayer, Tonelli, Oosthuizen & Surtee, 2018; Morris, 2002; Yaman, 2009). Salin (2001) points out that more women than men are exposed to mobbing, however, women experience more intense feelings in the aftermath of violence.

Lorenz (1982) argues that carnivores release their aggressive energy through ritual fighting in which they do not harm each other. However, humans do not have any protection mechanisms that suppress aggression. According to Freud (1993), the two important innate characteristics of human beings are sex and aggression. These two tendencies make social coherence harder to reach. Bullies cannot control their aggression instincts and they exert this dominant instinct on weaker individuals in particular, or on people with a possibility of gaining strength in the future. The research findings that indicate that women are more exposed to psychological violence compared to men are compatible with Freud's neuropsychological studies that regard women as physically weaker than men.

At universities the number of female academics receiving psychological counselling is higher than that of male academics. Field (1996) and Yaman (2009) state that mostly women receive psychological counselling, which indicates that women are more exposed to psychological violence than men at universities and state schools. The reasons why men receive less psychological counselling include not being exposed to psychological violence or not wanting to consider themselves weak to the extent that they need to receive psychological counselling.

The examination of the relationship between the teachers' levels of exposure to psychological violence and their performance perceptions in terms of demographic characteristics show a linear correlation among professional experience and participants' gender.

The results from this study show that teachers with six to ten years' experience were more exposed to psychological violence than teachers with sixteen to twenty years' experience. This finding demonstrates that young teachers with less experience are more likely to be victimised. Kilic's (2007) study shows that mobbing victims highlight that they were exposed to mobbing behaviour early in their professional lives. This result suggests that because young employees perform well, are dynamic and are willing to perform highly productive tasks, they are exposed to psychological violence by other employees at work.

Conclusion and Further Suggestions

Concrete and effective measures have not yet been taken to prevent mobbing. Mobbing is considered and addressed as arguing, conflict, and stress, and no awareness of mobbing exists in many countries and societies.

The results of this study show a negative relationship between mobbing and educational performance, while it also shows the way to enhance educational performance.

This study analysed the exposure levels of preschool and classroom teachers who work in primary educational institutions, to mobbing, and examined the impact of psychological violence on teachers' performance. The fewer victims who reported mobbing in the present study may be attributed to the non-autonomous corporate structure of primary educational institutions, and demographic and geographical characteristics. The examination of data in terms of demographic characteristics shows that exposure to mobbing was significantly related to gender, professional experience, and education level. Moreover, there was a significant relation between psychological violence and the perception of teachers' performance suggesting that psychological violence should be compared with other factors in future studies.

To prevent psychological violence in educational institutions, certain measures should be taken at an individual level. According to study, teachers who are exposed to psychological violence may suffer from emotional shock and worry, may not think clearly, which may lead to improper behaviour. At this point victims should exhibit strong and confident attitudes, and address and resolve any other problems in their personal lives to exhibit these strong attitudes.

Mobbing is shaped by a hierarchical structure, therefore, bullied teachers should try to increase their hierarchical importance in the organisation. Considering that lonely, defenceless, vulnerable, and weak individuals, particularly women, are more exposed to psychological violence, victims should present a strong facade to confirm that they are not alone and have strong institutional and individual powers supporting them.

Victims should strengthen their relationships with other people, excluding the bullies, learn how to recognise bullies, get to know bullies, search for background reasons of psychological violence, and cope with bullying accordingly.

Bullies' most significant weapons are victims' fear, whether work related or personal. Therefore, victims should be careful not to provide bullies with unintentional ammunition. Individuals should be confident, brave, and strong, and if necessary, claim their rights taking legal action.

Apart from the individual level, to prevent psychological violence at educational institutions, certain measures should be taken at institutional level. Objective criteria should be defined, and a well-defined performance assessment system should be designed with the cooperation of teachers and administrators. Teachers' weaker areas should be determined and developed; possible managerial problems at schools should be determined in advance, and when such problems arise, they should be resolved swiftly.

If preliminary efforts are made to raise consciousness and case studies analysed for possible psychological violence at educational institutions, small-scale signalling events can be noticed promptly. Moreover, basic principles of universal ethics should also be considered. Bullying victims mainly complain about groupings and isolation. Therefore, institution management should take measures to prevent groupings and isolation in the workplace.

In recent years mobbing in European countries has increased dramatically. At German universities courses on mobbing are presented as a sub-section of working psychology. In Sweden mobbing has become one of the significant reasons for early retirement, and the number of mobbing victims has exceeded one million in Italy (Ege, 1999; Ravisy, 2000).

As a first step in this struggle, past events and cases should be named and classified, necessary preventive measures should be taken, and information should be provided. Primary education teachers are responsible to shape the magical first years of primary learners' lives, therefore, consciousness of psychological violence inflicted on these teachers should be raised.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript, provided data for the tables, conducted all statistical analyses, and reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our supervisor, co-workers, and educational sciences specialists for their support in this study.

References

Akcakaya M 2012. Performance management and the problems encountered in application. The Research at Blach Sea, 32:171-202. [ Links ]

Andersson LM & Pearson CM 1999. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3):452-471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131 [ Links ]

Aquino K & Byron K 2002. Dominating interpersonal behavior and perceived victimization in groups: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Journal of Management, 28(1):69-87. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F014920630202800105 [ Links ]

Armstrong M 1996. Employee reward. London, England: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. [ Links ]

Aydin I 2009. Supervision on teaching. Ankara, Turkey: Pegem Akademi. [ Links ]

Bandow D & Hunter D 2008. Developing policies about uncivil workplace behavior. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 71(1):103-106. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1080569907313380 [ Links ]

Bayrak KS 2007. Psychological violence in business life and the reasons for intimidation. The Journal of Selcuk University Social Sciences, 16:433-448. [ Links ]

Blase J & Blase J 2003. The phenomenology of principal mistreatment: Teachers' perspectives. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(4):367-422. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230310481630 [ Links ]

Bowmen B, Stevens G, Eagle G & Matzopoulos R 2014. Bridging risk and enactment: The role of psychology in leading psychosocial research to augment the public health approach to violence in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 45(3):279-293. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0081246314563948 [ Links ]

Branch S, Sheehan M, Barker M & Ramsay S 2004. Perceptions of upwards bullying: An interview study. In S Einarsen & MB Nielsen (eds). Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Bergen, Norway: Department for Psychosocial Science. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29460127_Perceptions_of_Upwards_Bullying_An_Interview_Study. Accessed 30 December 2019. [ Links ]

Brown A 2005. Implementing performance management in England's primary schools. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 54(5/6):468-481. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410400510604593 [ Links ]

Canitez-Okur AB 2007. Emotional bullying at work, mobbing, the methods of handle: Industrial clinical psychology and management of human resource. Ýstanbul, Turkey: Beta Publishing. [ Links ]

Cogenli MZ & Asunakutlu T 2016. Mobbing in academy: An investigation at Adim Universities. Erzincan University Institute of Social Sciences Journal, 9(1):17-32. [ Links ]

Davenport N, Schwartz RD & Elliott GP 2002. Mobbing: Emotional bullying at work. Ýstanbul, Turkey: Sistem Publishing. [ Links ]

Davenport NZ 1999. Mobbing in workplace: Is it an epidemic? Article of Postgraduate, 12:1-2. [ Links ]

Demirel Y 2009. Psikolojik taciz davranýþýnýn kamu kurumlarý arasýnda karþýlaþtýrýlmasý üzerine bir araþtýrma [A study comparing the mobbing behaviour between public institutions]. Tisk Academi, 4(7):118-136. [ Links ]

Ege H 1999. Mobbing: Che cos'é il terrore psicologico sul posto di lavoro [Mobbing: What is psychological terror at work]. Bologna, Italy: Pitagora Editrice. [ Links ]

Field T 1996. Bullying in sight: How to predict, resist, challenge and combat workplace bullying: Overcoming the silence and denial. Didcot, England: Success Unlimited. [ Links ]

Fineman S, Gabriel Y & Sims D 2010. Organizing and organizations (4th ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Freud S 1993. My life and psikanaliz. Translated by K Sipal. Istanbul, Turkey: Say Publishing. [ Links ]

Garthus-Niegel S, Nübling M, Letzel S, Hegewald J, Wagner M, Wild PS, Blettner M, Zwiener I, Latza U, Jankowiak S, Liebers F & Seidler A 2016. Development of a mobbing short scale in the Gutenberg Health Study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89(1):137-146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1058-6 [ Links ]

Helvaci A 2002. The importance of performance evaluation in performance management process. Ankara University Journal of Educational Sciences, 35(1-2):155-169. [ Links ]

Henniger ML 1999. Teaching young children. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hoel H, Rayner C & Cooper CL 1999. Workplace bullying. In CL Cooper & IT Robertson (eds). International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 14). Chichester, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [ Links ]

Hornstein HA 1996. Brutal bosses and their prey. How to identify and overcome abuse in the workplace. New York, NY: Riverhead Books. [ Links ]

International Labour Organization n.d. Violence at work - A major workplace problem. Available at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/genericdocument/wcms_108531.pdf. Accessed 2 January 2017. [ Links ]

Karasar N 2004. The methods of scientific researches. Ankara, Turkey: Nobel Publishing. [ Links ]

Kilic ST 2007. Mobbing, mobbing enforcements at the industry, individual effects, organizational and social costs. MEd dissertation. Eskiþehir, Turkey: Anadolu University. [ Links ]

Kulpcu O 2009. A study on the motivation tools that can be used to motivate teachers and administrators working in elementary schools (Gaziantep sample). MEd dissertation. Gaziantep, Turkey: Gaziantep University. [ Links ]

Leymann H & Gustafsson A 1996. Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2):251-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414858 [ Links ]

Lodge D 2001. Thinks. New York, NY: Viking Press. [ Links ]

Lorenz K 1982. Vergleichende verhaltensforschung: Grundlagen der ethologie [Comparative behavioral research: Fundamentals of ethology]. München, Germany: Grundlagen der Ethologie DTV Wissenschaft. [ Links ]

Mathias JL, Mertin P & Murray A 1995. The psychological functioning of children from backgrounds of domestic violence. Australian Psychologist, 30(1):47-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050069508259606 [ Links ]

Mayer CH, Tonelli L, Oosthuizen RM & Surtee S 2018. 'You have to keep your head on your shoulders': A systems psychodynamic perspective on women leaders. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 44(1):a1424. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1424 [ Links ]

Menesini E, Sanchez V, Fonzi A, Ortega R, Costabile A & Lo Feudo G 2003. Moral emotions and bullying: A cross-national comparison of differences between bullies, victims and outsiders. Aggressive Behavior, 29(6):515-530. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10060 [ Links ]

Morris A 2002. Critiquing the critics: A brief response to critics of restorative justice. The British Journal of Criminology, 42(3):595-615. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/42.3.596 [ Links ]

Ozkalp E & Kirel C 2001. Organizational behaviour. Eskisehir, Turkey: T.C. Anadolu University Education, Healthy and Scientific Research Studies Foundation. [ Links ]

Özözen Danacý M 2009. The scale of teachers' performance perception. MEd dissertation. Sakarya, Turkey: Sakarya University. [ Links ]

Pillay SR 2016. Silence is violence: (Critical) psychology in an era of Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2):155-159. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0081246316636766 [ Links ]

Ravisy P 2000. Le harcélement moral au travail [Moral harassment at work]. Paris, France: Delmas. [ Links ]

Salin D 2001. Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: A comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4):425-441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000771 [ Links ]

Sheehan M, Barker M & Rayner C 1999. Applying strategies for dealing with workplace bullying. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2):50-57. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268632 [ Links ]

Sheridan H & Rice E 1991. Difficult dialogues: Achieving the premise in diversity. Paper presented at the National Conference on Higher Education, Washington, DC, 10-15 February. [ Links ]

Tinaz P 2006. Bullying at work: Mobbing. Istanbul, Turkey: Beta Publishing. [ Links ]

Tutar H 2004. Psychological violence in the workplace is spillover: Causes and consequences. The Journal of Management Sciences, 2(2):92-104. [ Links ]

Vartia-Väänänen M 2003. Workplace bullying - A study on the work environment, well-being and health. PhD thesis. Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/35947078_Workplace_bullying_A_study_on_the_work_environment_well-being_and_health. Accessed 10 December 2019. [ Links ]

Yaman E 2009. The validity and reliability of the Mobbing Scale (MS). Kuram ve Uygulamada Eðitim Bilimleri [Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice], 9(2):981-988. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ847787.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2019. [ Links ]

Zapf D 1999. Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2):70-85. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437729910268669 [ Links ]

Received: 29 May 2018

Revised: 29 January 2019

Accepted: 9 July 2019

Published: 29 February 2020.