Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1559

ARTICLES

A hope-based future orientation intervention to arrest adversity

Gloria Marsay

Department of Practical and Missional Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. marsay@global.co.za

ABSTRACT

Hope has been identified as a key element to success in planning one's future. An attitude of hope opposes feelings of despair and can sustain one through adversity. The study reported on in this article is based on the premise that everyone needs hope to thrive and that educators can be providers of hope for the future, since they are responsible for building capacity in young people. Educators can assist young people towards successful transition from school to tertiary education and training, before entering the world of work, by focusing on practical interventions. The prevailing difficulties within the economic-socio-political arena contribute to ubiquitous feelings of helplessness and hopelessness among both privileged and disenfranchised people. The intention of this case study was to explore the efficacy of a hope-based future orientation intervention to arrest the negative impact of adversities faced by a university student. The participatory action research approach was used to gain insight into the experiences of the participant. The analysis was qualitative. The efficacy of this intervention, which uses constructs of hope as a unique foundation, is discussed.

Keywords: education; future orientation; guidance; hope; livelihood; work

Background

Despite good policy, many South African young people receive only fragile guidance and preparation for the future. The Department of Higher Education and Training (2016) reveals that 68% of South Africa's unemployed people are between 15 and 34 years old. Most South Africans receive a limited form of guidance as part of a compulsory school subject, Life Orientation. However, although this could be an effective approach, educators who present Life Orientation have limited training on today's dynamic world of work. An impact study done by South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) reveals that the targeted areas of access, redress, equity, quality, and efficiency set by the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) have not yet been attained (SAQA, 2016). A climate of social instability and exclusion pervades. A plethora of challenges hinders the individual's drive towards autonomy, self-determination, purpose, and employability.

The problem addressed in this article is twofold. Firstly, the prevailing difficulties within the economy and the #FeesmustFall protests highlight that institutions of higher education and training in South Africa are presently in crisis, not only regarding funding and fee structure, but also pedagogically. The protests have had a pervasive negative impact on all learners. (Msila, 2016). Secondly, there is a lack of guidance and adequate preparation for the future regarding the transition between secondary education and tertiary education and training. These two disempowering discourses contribute to ubiquitous feelings of despair and hopelessness among both privileged and disenfranchised people. Consequently, young people's hope for a successful future is diminished.

Clearly, it is necessary to find ways to instil and restore hope among the South African youth, while at the same time empowering them with effective skills to make realistic decisions, set appropriate goals and plan a sustainable livelihood. This article is based on the premise that everyone needs hope to thrive and that professionals, including educators, who assist young people can be providers of hope for the future, since they are responsible for building capacity in young people (Botman, 2007). The intention of the article is to explore the efficacy of a hope-based intervention.

Literature Review

A growing body of research shows evidence that hope has important implications for personal development in the face of adversity and has been identified as a key element to success in planning one's future. Interventions designed using the theory of hope have been researched globally.

A study conducted by Cheavens, Feldman, Gunn, Michael and Snyder (2006) provides promising evidence about the initial efficacy of a group intervention to increase hope and enhance strengths. Findings suggest that by turning attention to hope there is likely to be movement toward increasing human potential, individually and collectively. Diemer and Blustein (2007) suggest that urban adolescents may benefit from interventions that facilitate their vocational hope and connection to their vocational future. After the earthquake in Haiti, Scioli and Charles (2012) successfully piloted the Hip Hope Intervention with youths. Results of the study conducted by Amundson, Niles, Yoon, Smith, In and Mills (2013) in a collaborative study conducted in Canada and the United States of America confirmed the hypothesis of a significant pathway from hope to school engagement to vocational identity and higher academic achievement. In a study with a group of workers with intellectual disability conducted by Santilli, Nota, Ginevra and Soresi (2014) in North-east Italy, a significant link between career adaptability, hope, and life satisfaction was identified. Elez (2014), in a study that focused on working with immigrant clients, and Smith, Mills, Amundson, Niles, Yoon and In (2014) in a study that focused on participants who experienced a high level of barriers, report that being hopeful about one's ability and one's future is essential to success.

In the South African context, studies using hope-based interventions to instil hope in people who have experienced adversity have been piloted. A focused ethnographic research approach with disenfranchised young sexual offenders in a group context (Marsay, Scioli & Omar, 2018) illustrated the efficacy of the broad-based hope-based approach. There was evidence indicating the that four constructs of hope, as described by Scioli and Biller (2009, 2010), namely attachment, survival, mastery, and to some degree spirituality, had been enhanced. The participants were able to make better choices in their relationships, seek out appropriate social support, and set realistic goals for their future. A qualitative case study (Marsay, 2016a) demonstrates the efficacy of the hope-based intervention. The participant was a young lady who was experiencing physical and emotional difficulties. Findings in this study illustrate the efficacy of a multidisciplinary approach and the empowering ability of the hope-based intervention. The participant was able to make preferred choices regarding her future studies, establishing meaning and purpose for her newly made choices. The study illustrates how the participant used the constructs of hope to assist her in seeking out appropriate social support, managing her ability to concentrate, and cope more effectively when faced with adversity.

Literature regarding guidance and counselling approaches used globally suggests the importance of self-determination, and how self-determination is linked to attitude (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wehmeyer & Little, 2013). In a study conducted in South Africa to understand what contributed to success of disenfranchised people in the world of work, self-determination was found to be an essential personality trait in circumventing adversity (Marsay, 2014). Findings show how participants were able to benefit from acquiring personal competencies and marketable skills (mastery); they had the ability to use creative ways to circumvent and overcome adverse conditions (survival); they made good use of social support structures (attachment); and they had a sense of purpose and mission for their lives (spirituality). In summary, those who were successful in the world of work showed evidence of making effective use of the four constructs of hope (Scioli & Biller, 2009, 2010).

Theoretical Framework

Throughout the world scholars are recognising that hope is an attitude which becomes especially important when people are faced with insecurity and adversity (Amundson et al., 2013; Ginevra, Sgaramella, Ferrari, Nota, Santilli & Soresi, 2017; McNenny & Osborn, 2015; Scioli & Biller 2009, 2010; Scioli, Ricci, Nyugen & Scioli, 2011; Snyder, 2000; Snyder, Feldman, Shorey & Rand, 2002). McNenny and Osborn (2015) who write about global sustainability in education, state that a pedagogy of hope, into which emerging awareness, acceptance, and action can be successfully integrated, is available to us as educators, if together with our students, we claim the courage to do so.

Several scholars in South Africa refer to the pedagogy of hope described by Freire (1992) as an important way forward for South African young people (Botman, 2007; Dreyer, 2011; Le Grange, 2011; Van Louw & Beets, 2011). Le Grange (2011) asserts that hope is meaningless if it is not anchored in practice. The intention of this study was to illustrate how hope can be learnt, shared, and practiced.

Snyder (2002:249) defines hope as the perceived capability to derive pathways to desired goals and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways. Scioli and Biller (2009, 2010) describe fundamental hope as a stable character-strength that is a future-directed, four-channel emotion network, constructed from biological, psychological, and social resources. These resources are channelled into four constructs: attachment, mastery, survival and spirituality.

Furthermore, Scioli and Biller (2009, 2010) suggest that hope, characterised as a strength or skill, can be learned. This is an important insight because hope is often diminished by the challenges and barriers that confront the South African youth, as discussed earlier. The fact that hope as a skill can be learned, is liberating. The theoretical framework postulated by Scioli and Biller (2009, 2010), combined with the alternate approach to making decisions for the world of work researched by the author (Marsay, 2000) is used in this case study.

Methodology

To explore the efficacy of a hope-based intervention participatory action research was used in the case study described in this article. The approach taken in this case study was education action research (Adelman, 1993), which is a subset of participation action research (MacDonald, 2012; Morales, 2016; Reason & Bradbury, 2008). The purpose of action research is to produce practical knowledge that is useful in everyday contexts of people's lives and to contribute to increased well-being - economically, politically, psychologically, and spiritually (Reason & Bradbury, 2008:4). Participation action research has the potential to result in acceptable and sustainable educational innovations since it involves participation of significant stakeholders (Mubuuke & Leibowitz, 2013).

Participation action research can blur the distinction between research and practice. As an educational psychologist in practice, I have a special interest in helping vulnerable students to reach their full potential. I have adopted a dual role as researcher wishing to find a way to assist students with overwhelming problems (Schein, 2008). As researcher I acknowledge the importance of reflexivity, taking time to consider my position of power, and the way in which I share my power in practice. I communicate my expectation of wanting to develop a useful intervention honestly and authentically to the participant. The participant has knowledge of his difficulties, and I have knowledge of processes which may assist the participant. Participant action research as explained by Lewin (Adelman, 1993:13) assumes that the person needing help must be involved in the research process from the start.

Participant

The participant was purposively chosen because he expressed difficulties. He was not succeeding in his chosen tertiary education field, and he was experiencing extreme disabling anxiety. He was feeling helpless and hopeless during his second attempt at first year university studies. The participant was 21 years old when he sought assistance. Together, the participant and I planned the intervention, took action, observed and reflected on the outcome over a period of time, using the structure suggested by Steyn and Vlachos (2011).

Data Collection

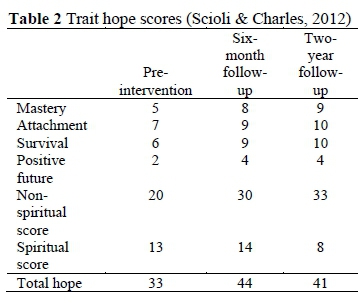

Data was collected using an objective and subjective mixed methods approach. Objectively the participant completed two self-report questionnaires. Snyder, Harris, Anderson, Holleran, Irving, Sigmon, Yoshinobu, Gibb, Langelle and Harney's (1991) Trait Hope Scale is a 12-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess hope in adults. Items are scored using an eight-point Likert scale and scores are created for overall hope. Items 1, 4, 6 and 8 make up the pathway subscale and items 2, 9, 10 and 12 make up the agency subscale. Scioli's questionnaire, Trait Hope Split Half Form A (Scioli & Charles, 2012) was completed pre-intervention. Snyder's Adult Trait Hope Scale was repeated after a six-month period, and Scioli's Trait Hope Split Half Form B was completed after a six-month period. Both these self-report questionnaires were used to gain in-depth insight into all aspects of hope as stated by the different theorists. A comparison of these scores is illustrated in Tables 2 and 3 in the results section.

During follow-up interviews six months, one year and two years later, the participant was invited to evaluate the process in conversations with the researcher. Relevant verbatim quotes give voice to the participant's experiences.

Data Analysis

By engaging in an iterative, cyclic, and self-reflective process the participant and I made meaning of the data collected. Preliminary subjective interpretations were challenged, and data was revisited after six and twelve months (Higginbottom, Pillay & Boadu, 2013). The assessment on rigour in this study was performed using the criteria of credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The participant read and confirmed that this case study was a true reflection of his experiences.

Ethical Considerations

This study strictly adhered to the principles of respect and protection, transparency, scientific and academic professionalism, and accountability, stated by the Human Sciences Research Council (2019). Informed consent was obtained from the participant at the beginning of the process. The participant was included in all decision-making regarding the research process and the intervention. The participant was briefed on the aims and implications of the research and he consented to this data being shared for the benefit of others (Denny, Silaigwana, Wassenaar, Bull & Parker, 2015).

Case Study

The participant was a young man, Sean, (pseudonym for the purposes of this article) who sought help during his second attempt at first year at university. He identified two problems. Firstly, he thought that he had chosen the wrong study pathway, because he was not motivated and found the content of the course difficult. Secondly, he found his level of anxiety debilitating. Sean's request for assistance coincided with the #FeesmustFall protest at its most intense. He was filled with despair and anxiety because of the unrest and he was not coping academically. He was unable to attend lectures and found it difficult to study on his own because he could not concentrate. During the protests, classes were disrupted and students were prevented from attending lectures and writing exams. Precious study time was lost. Exams were eventually written in a tense environment with strict security procedures which exacerbated Sean's anxiety - a result of his historic struggles with several criteria of Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). GAD criteria are excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least six months, about several events or activities (such as work or school performance) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sean also displayed evidence of ADD. He showed a persistent pattern of inattention, was prone to making careless mistakes, struggled to hold attention, was unable to follow through on instructions, failed to finish tasks because he lost focus, struggled to organise tasks, tended to avoid doing tasks that required mental effort, and was easily distracted by his surroundings and/or thoughts. He was diagnosed with ADD before he was 12 years old and was prescribed Concerta. The ADD symptoms interfered with his social and academic functioning. He did not work well under pressure and found social interaction difficult. Once he started university, he took Serta as an anxiolytic.

Sean completed the Grade 12 examinations in 2014 and passed with university entrance grades in English, Afrikaans, Mathematics, and Life Orientation as compulsory subjects, and Physical Sciences, Geography, and History as chosen subjects. He identified Geography as the subject which he enjoyed the most. At school he was provided with career guidance using psychometric computer-based testing. Sean said: "I completed computer-based tests that pointed to engineering as the best option. It also seemed like a good choice at the time. There was very little human interaction associated with these tests." Based on the results from the computer-based test he chose to study engineering. Sean struggled during his first year at university and found the volume of work overwhelming. He felt that he had not been adequately prepared to cope with the emotional and academic demands of tertiary education. As a result of this floundering during his first year, he decided to change course for his second year. He converted to a Bachelor of Commerce, because he believed that this course would offer him a good foundation in the future world of work, and he thought it would be less difficult. However, as the course progressed, he found that he was again floundering. He had no background of business and economics as he had not taken these subjects at school and lacked interest in these subjects.

Based on this history, Sean agreed to participate in the hope-based intervention, which consisted of 6 hour-long sessions conducted one on one.

The intervention

The steps taken in this intervention (see Table 1) were influenced by those suggested by Steyn and Vlachos (2011:27), which include a needs analysis, planning and development, implementation, managing the work, the resources and the people, and evaluation. A preliminary session involved discussion around the participant's present situation and past experiences. The participant and I completed a needs analysis of what he expected the outcomes of the intervention would be. During this session the participant was briefed about the research exercise and invited to consider being a participant in the project. The processes of participation action research and hope-based intervention was explained to him in detail. He was given time to consider the invitation, agree to participation and he was assured that he could withdraw from the programme at any time, should he choose to do so. The intervention strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines in health research as prescribed by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA, 2008). The principle of best interest or well-being, the principle of respect for persons, and the principle of justice were all adhered to in this intervention.

Examples of questions

The exact questions used in the discussion cannot be provided as each question asked was dependent on the answer to the previous question. However, the questions listed in Figure 1 are examples of questions which form the framework for the hope-based intervention.

Results

The outcome of the intervention was positive. Sean changed his course to follow a Bachelor of Science (BSc) course in Geoinformatics, his preferred field of study. This course was more congruent with his chosen subjects at school and his high interest in Geography.

Scores of Scioli's Trait Hope Scale and the Snyder's Adult Trait Hope Scale were compared. Sean's trait hope (Scioli & Charles, 2012) scores improved to a total hope improvement of 33%, as illustrated in Table 2. His non-spiritual score improved from 20 to 30 points (50% increase), with the most significant increase being in the mastery and survival scores. Sean's total hope score on the Adult Trait Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1991) showed an increase of 10.6% as illustrated in Table 3. Both pathway and agency subscales increased.

This intervention did not target spirituality. This construct of hope is very personal and is influenced by factors that were not examined in this study. The focus of this study was on developing skills to enhance mastery, attachment, and survival. The increase in these scores is evident over the two years.

These subscales increased after the intervention and then remained stable after a period of two years. It is very difficult to quantify feelings of hope, which are abstract by nature. However, these scores show how the constructs of hope have at least remained constant over a period of two years. The verbatim quotes give a rich description of how Sean managed to set goals, make decisions, and remain hopeful regarding his ability and his future vocational pathway. Sean selected his new pathway because, he said that

something to do with Geography was always on my radar. I knew something about it and did research around different courses offered by universities.

Sean and I discussed possible job opportunities using Geography as a major and he did some job-shadowing before he made his selection.

Verbatim Quotes

Sean felt that the techniques of the survival component (controlling anxiety and focusing attention) of the intervention assisted him the most. He was able to seek and receive assistance from his support group of fellow students, indicating the efficacy of the attachment component. Furthermore, Sean stated that the practical skills he had learnt in the mastery component (study skills and exam techniques) of the intervention were useful to him. Sean could focus and apply himself to his studies more easily. Sean was able to use academic support available to him. He also remembered and used the survival meditation (Scioli & Charles, 2012) when he felt anxious. He found the use of the emotion freedom tapping techniques useful in times of anxiety. Sean also realised that when faced with adversity it was not the "end of the world," and that his attitude "became more positive and hopeful." Six months after the initial intervention Sean was asked to evaluate his progress. He was asked: How is uni going? How is the new course working for you?, to which he replied as follows:

I am really enjoying my new courses this semester I am really finding them interesting. I unfortunately failed one subject, Programming, but I will be taking again next year. The rest I did pass which I am have happy about that as it is a big step forward for me compared to previous years! I am much happier and getting all my work done in a much more effective way!

At the beginning of his second year, I contacted Sean to follow up on his progress. Sean wrote:

Uni is going quite well at the moment am enjoying it a lot more than I did in the past and am finding it easier to work like I need to be. The atmosphere seems to be good but if anything happens it usually happens around exams so we will have to hope for the best.

Halfway through his second year, Sean wrote:

It wasn't my best semester unfortunately. I did fail a module which I am quite down about but am at a winter school for it now so hoping it doesn't hold me back if I can manage to pass now. It is a bit of a hit but am dealing with it alright.

At the beginning of his third year of study Sean reported:

I am in my last year of my undergrad now so will hopefully be done at the end of this year! Last year went quite well thank you, did really struggle with one module but managed to pass it in the end so everything is on track … For me personally I can say the techniques that helped the most were the calming techniques you gave me with the tapping one [EFT] being the one that still works well for me. But on a bigger scale your reassurance about my University situation and also your insight into the job market and potential jobs really helped me a lot and put me at ease a lot.

When asked about the effectiveness of medication, Sean replied:

The meds have helped me get through my day-to-day activities, keep my head above water, while our work [the hope intervention] has helped in the long run with life in general.

Sean's mother wrote the following:

Sean is in 3rd year already - can you believe it after the two years of confusion and often sadness. The course did change from when he started it and it probably does not offer the 'human / geography' aspect that he was looking for and it has become more IT [Information Technology] slanted. Although not naturally his aptitude, he has nevertheless plodded on, doing summer schools and supplementary exams on the way. He is hanging in … and can see a future and is starting to email a few relevant companies for work experience opportunities. He is still taking Serta and Concerta when needed. We're just ticking off the months now. Thank you for making him not be afraid to change and that things take time.

Discussion

Part of the subjective internal work embraced by the hope-based intervention is to bolster fundamental hope as a unique foundation, based on the four constructs of attachment, mastery, survival and spirituality (Scioli & Biller, 2009, 2010). The results illustrated in Table 2 indicate that all the constructs of hope were enhanced and were consistent with findings from previous studies in the South African context (Marsay, 2014, 2016a; Marsay et al., 2018). Sean's ability to set goals for himself, to plan pathways, and to exercise personal agency is illustrated in Table 3.

Sean's verbatim quotes illustrate his sustained progress over a period of two and a half years. The hope-based intervention empowered Sean to work more effectively, to seek assistance when he needed it, to persevere when he faced adversities (he sought assistance through winter school when he failed one subject). When examining the verbatim quotes, the reader can understand how Sean became more self-determined and hopeful. The quote from Sean's mother shows his ability to persevere. He demonstrates vocational hope and has connected to his vocational future as described by Diemer and Blustein (2007). Sean's positive trajectory confirms the hypothesis of Amundson et al. (2013) of a pathway from hope to school engagement, to vocational identity, and to higher academic achievement. Sean's ability to move forward in his chosen pathway after the intervention, resonates with the findings of studies discussed in the literature review. This study supports the link between being hopeful about one's ability and one's future, and success.

The work involved making effective use of external opportunities and resources available for example (Sean's decision to join winter school), which offered him academic support, requires self-determination as explained by Wehmeyer and Little (2013). Sean's ability to exercise personal agency and become self-determined can be regarded as an essential key to his success. The results of this case study also resonate with the study illustrating the importance of self-determination described in the literature review (Marsay, 2014). Sean was able to benefit from acquiring personal competencies. He was able to study more effectively (mastery); he displayed the ability to use calming strategies when he needed them to overcome adverse conditions (survival); he made good use of support structures by attending winter school (attachment); and he had developed a sense of purpose for his studies (spirituality). These results are comparable with the results of the pilot study conducted in the South African context (Marsay, 2016a; Marsay et al., 2018).

We are now faced with two questions. Was the success of the intervention a result of developmental maturation that stimulated motivation? It is important to note that the essential skills that Sean had identified as being underdeveloped were learnt and strengthened during the intervention, which concurs with Scioli and Biller (2009), that hope can be learned. As being reported in the literature review, hope is a key element to success.

The second question: Was the success of the intervention a result of on-going support from the researcher? Perhaps this question emphasises the importance of the construct of attachment to bolster hope and consequently sustain achievement, as illustrated in the case studies discussed in the literature review.

Limitations and Future Directions

One of the drawbacks of qualitative research studies is that events, cases, processes, situations, individuals, and their behaviour are unique, context-dependent and thus, not generalisable. Hence, the primary limitation of this study was that it comprised only one case study. However, the study can be replicated, and the findings of other pilot studies can be compared to provide clarity (Marsay, 2016a; Marsay et al., 2018).

Scioli (2007:143) states that no continent is more hope-challenged than Africa. In developing countries community members are in the best position to assist young people with their transition into the world of work (Arulmani, 2014; Marsay, 2016b; Watts, 2009). It may be prudent for educators as prominent members of the community to take up the social responsibility of assisting learners towards a successful future (Dreyer, 2011; Le Grange, 2011; Marsay, 1996). A successful future can be accomplished by instilling and restoring hope using a hope-infused approach towards the future, provided that, at all levels, the process is guided by a professional with specialised clinical experience. While this work is exploratory and opinion based, it is worthy of further research in the South African context. Future studies could examine the efficacy of the programme with young people who are making the transition from secondary education to tertiary education and training. Perhaps we, as educators, can help our young people by having the courage to practice the four constructs of hope with them.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to acknowledge the input from the participant whose voice is captured in this article and thanks him for his contribution to this study.

References

Adelman C 1993. Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1(1):7-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102 [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). Arlington, VA: Author. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ Links ]

Amundson N, Niles S, Yoon HJ, Smith B, In H & Mills L 2013. Hope-centred career development for university/college students. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling. Available at http://ceric.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/CERIC_Hope-Centered-Career-Research-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed 12 February 2020. [ Links ]

Arulmani G 2014. Career guidance and livelihood planning. Indian Journal of Career and Livelihood Planning, 3(1):9-11. Available at http://www.iaclp.org/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/3_Gideon_Arulmani_IJCLP_Vol_3.43213432.pdf. Accessed 10 February 2020. [ Links ]

Botman HR 2007. A multicultural university with a pedagogy of hope for Africa. Inaugural address, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 11 April. Available at https://digital.lib.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.2/4436. Accessed 3 June 2019. [ Links ]

Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Gum A, Michael ST & Snyder CR 2006. Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. Social Indicators Research, 77(1):61-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5553-0 [ Links ]

Denny S, Silaigwana B, Wassenaar D, Bull S & Parker M 2015. Developing ethical practices for public health research data sharing in South Africa: The view and experiences from a diverse sample of research stakeholders. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 10(3):290-301. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1556264615592386 [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training 2016. Draft policy: Building an effective and integrated career development services system for SA. Available at http://www.nstf.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Policy-Brief_Building-Career-Dev-Services-System_final.pdf. Accessed 3 June 2019. [ Links ]

Diemer MA & Blustein DL 2007. Vocational hope and vocational identity: Urban adolescents' career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(1):98-118. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1069072706294528 [ Links ]

Dreyer LM 2011. Hope anchored in practice. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(1):56-69. [ Links ]

Elez T 2014. Restoring hope: Responding to career concerns of immigrant clients. Revue Canadienne de Développement de Carrière [The Canadian Journal of Career Development], 13(1):32-45. Available at http://cjcdonline.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/CJCD-Complete-Vol-13-1.pdf#page=34. Accessed 5 February 2020. [ Links ]

Freire P 1992. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. London, England: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Ginevra MC, Sgaramella TM, Ferrari L, Nota L, Santilli S & Soresi S 2017. Visions about future: A new scale assessing optimism, pessimism, and hope in adolescents. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 17:187-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-016-9324-z [ Links ]

Health Professions Council of South Africa 2008. Booklet 6: General ethical guidelines for health researchers. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/6/files/hpcsa-ethical-guidelines-for-researchers.zp158370.pdf. Accessed 3 June 2019. [ Links ]

Higginbottom GMA, Pillay JJ & Boadu NY 2013. Guidance on performing focused ethnographies with an emphasis on healthcare research. The Qualitative Report, 18:1-16. https://doi.org/10.7939/R35M6287P [ Links ]

Human Sciences Research Council 2019. Code of research ethics. Available at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/about/research-ethics/code-of-research-ethics. Accessed 3 June 2019. [ Links ]

Le Grange L 2011. A pedagogy of hope after Paulo Freire. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(1):183-189. Available at https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/high/25/1/high_v25_n1_a14.pdf?expires=1580880739&id=id&accname= guest&checksum=EE8C451743CA2A1885FE9714CF1AEA06. Accessed 5 February 2020. [ Links ]

Lincoln YS & Guba EG 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

MacDonald C 2012. Understanding Participatory Action Research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2):34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 [ Links ]

Marsay G 2014. Success in the workplace: From the voice of (dis)abled to the voice of enabled. African Journal of Disability, 3(1):99. https://doi.org/10.4102%2Fajod.v3i1.99 [ Links ]

Marsay G 2016a. Jumping hurdles in life using best practice interventions - A hope filled case study. International Journal of Psychology, 51:474. [ Links ]

Marsay G 2016b. The psychology of hope and earning a livelihood in South Africa. Available at https://thoughtleader.co.za/psyssa/2016/10/18/the-psychology-of-hope-and-earning-a-livelihood-in-south-africa/. Accessed 17 February 2020. [ Links ]

Marsay G, Scioli A & Omar S 2018. A hope-infused future orientation intervention: A pilot study with juvenile offenders in South Africa. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(6):709-721. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1480011 [ Links ]

Marsay GMD 1996. Career and future orientation of learners as a responsibility of the teacher. MEd dissertation. Johannesburg, South Africa: Rand Afrikaans University. Available at https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/%20access/manager/Repository/uj:9697?view=list&f0=sm_subject%3A%22Schools+--+Aims+and+objectives%22&sort=sort_ss_sm_creator+asc. Accessed 17 February 2020. [ Links ]

Marsay GMD 2000. Narrative ways to assist adolescents towards the world of work: Never ending stories ... bound to change. PhD thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: Rand Afrikaans University. [ Links ]

McNenny G & Osborn J 2015. Discourses of hope in sustainability education: A critical analysis of sustainability advocacy. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10. Available at http://www.jsedimensions.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/McNenny-Osborn-JSE-Nov-2015-Hope-Issue-PDF.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2020. [ Links ]

Morales MPE 2016. Participatory Action Research (PAR) cum Action Research (AR) in teacher professional development: A literature review. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 2(1):156-165. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105165.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2020. [ Links ]

Msila V 2016. #FeesMustFall is just the start of change. Mail & Guardian, 20 January. Available at http://mg.co.za/article/2016-01-20-fees-are-just-the-start-of-change. Accessed 3 June 2019. [ Links ]

Mubuuke AG & Leibowitz B 2013. Participatory action research: The key to successful implementation of innovations in health professions education. African Journal of Health Profession Education, 5(1):30-33. https://doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.208 [ Links ]

Reason P & Bradbury H (eds.) 2008. The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Ryan RM & Deci EL 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1):68-78. [ Links ]

Salomon S 2011. It is in your hands: Emotional freedom technique (EFT) (2nd ed). Ambler, PA: SpiralPress. [ Links ]

Santilli S, Nota L, Ginevra MC & Soresi S 2014. Career adaptability, hope and life satisfaction in workers with intellectual disability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1):67-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.02.011 [ Links ]

Schein EH 2008. Clinical inquiry/research. In P Reason & H Bradbury (eds). The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Scioli A 2007. Hope and spirituality in the age of anxiety. In RJ Estes (ed). Advancing quality of life in a turbulent world. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Scioli A & Biller HB 2009. Hope in the age of anxiety: A guide to understanding and strengthening our most important virtue. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Scioli A & Biller HB 2010. The power of hope: Overcoming your most daunting life difficulties-no matter what. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications. [ Links ]

Scioli A & Charles W 2012. HIP HOPE: A workshop for building hope in young people of all faiths. [ Links ]

Scioli A, Ricci M, Nyugen T & Scioli ER 2011. Hope: Its nature and measurement. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3(2):78-97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020903 [ Links ]

Smith BA, Mills L, Amundson NE, Niles S, Yoon HJ & In H 2014. What helps and hinders the hopefulness of post-secondary students who have experienced significant barriers. Revue Canadienne de Développement de Carrière [The Canadian Journal of Career Development], 13(2):59-74. Available at http://ceric.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/What-Helps-and-Hinders-the-Hopefulness-of-Post-Secondary-Students.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2020. [ Links ]

Snyder CR (ed.) 2000. Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. London, England: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Snyder CR 2002. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4):249-275. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01 [ Links ]

Snyder CR, Feldman DB, Shorey HS & Rand KL 2002. Hopeful choices: A school counsellor's guide to hope theory. Professional School Counselling, 5(5):298-308. [ Links ]

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C & Harney P 1991. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4):570-585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority 2016. Assessment of the impact of the South African National Qualifications Framework (NQF): Data and information highlights from the 2014 NQF impact study. Waterkloof: Author. Available at http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/papers/2016/2016%2002%2004%20DATA%20HIGHLIGHTS%20100-page%20BOOKLET%202014%20NQF%20Impact%20Study.compressed.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2020. [ Links ]

Steyn GM & Vlachos CJ 2011. Developing a vocational training and transition planning programme for intellectually disabled students in South Africa: A case study. Journal of Social Sciences, 27(1):25-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2011.11892903 [ Links ]

Van Louw T & Beets PAD 2011. Towards anchoring hope. South African Journal of Higher Education, 25(1):168-182. Available at https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/high/25/1/high_v25_n1_a13.pdf?expires=1580478398&id=id &accname=guest&checksum=3A246835054ADA80F8197FB3AECA2BD3. Accessed 31 January 2020. [ Links ]

Watts T 2009. The role of career guidance in the development of the National Qualifications Framework in South Africa. In South African Qualifications Authority. Career guidance challenges and opportunities. Hatfield, South Africa: South African Qualifications Authority. Available at http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/genpubs/2009/career_guidance.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2020. [ Links ]

Wehmeyer ML & Little TD 2013. Self-determination. In ML Wehmeyer (ed). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Received: 7 July 2017

Revised: 19 April 2019

Accepted 3 August 2019

Published: 29 February 2020.