Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 suppl.1 Pretoria Sep. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1537

ARTICLES

"You can be anything" - Career guidance messages and achievement expectations among Cape Town teenagers

Katherine Morse

Department of Sociology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa. kathm71@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Do high school learners in Cape Town have realistic tertiary study plans? During 2015, 813 Grade 11 learners were surveyed with regard to their expectations for academic achievement and post-school plans. Learners attended average-performing, no- or low-fee Cape Town high schools. Follow-up discussions were held with 10 learners, 2 teachers and 1 family. In line with previous South African studies, it was found that almost all Grade 11 learners expected to study at tertiary level. Although learners expressed confidence that they would achieve their goals, 70% predicted that their school marks would increase over the following 15 months to an unlikely or impossible degree. Learners in the lowest quartile of school performance were most at risk of overestimating their future improvement and, additionally, reported that their current marks were higher than reflected in school records. Young people are encouraged to plan for university education without consideration of how realistic or attainable this option is for them. They are repeatedly told: "You can be anything!" Some learners moderate this message with practices of self-regulated learning, involving careful checking of recent marks, setting goals, and reviewing progress. Others pretend to have marks that they do not have and rely on the power of self-belief to make their expectations a reality. This leads to a likely mismatch between plans and actual academic attainment.

Keywords: achievement; career guidance; goal setting; self-belief; teenagers; tertiary education

Introduction

Young people in Cape Town, like their counterparts internationally, have high expectations of accessing tertiary education. This study focused on Coloured and Black African learners in Grades 11 and 12.i The study found that young people have highly unrealistic expectations given their current academic achievement level and the historic performance of their school. These unrealistic expectations are enforced by a dominant community message: "You can be anything!" This message is heard from politicians, teachers, and parents. The emerging Black middle class and the story of the "one who made it" serve as evidence to support the message. The result is that many young people make plans for unattainable goals while neglecting to explore realistic possibilities (Bray, Gooskens, Kahn, Moses & Seekings, 2010). In South Africa 50% of young people of school-leaving age are not in employment, education or training (NEETs), (Branson, Lam & Zuze, 2012). We need to ask serious questions about what is being done to prepare young people for life beyond high school.

The South African Context

The high school life orientation curriculum expects of learners to settle on and describe a career pathway that they expect to follow (Department of Education, 2003). Learners tend to choose professional careers that require tertiary study and teachers encourage them to explore university options (Bray et al., 2010). Learners and teachers fail to make the link between current academic performance and likely access to tertiary education. There is often a sense that they might "get lucky" with an application and that "everyone should try for university." Young people from impoverished backgrounds rarely consider obstacles or make contingency plans (Bray et al., 2010).

When 20-year-olds are asked why they are not attending an educational institution, only 5% state that they have completed their education (Statistics South Africa, 2014). Many still believe that they are going to go on to tertiary education even after years of failing to gain access to a tertiary course (Bray et al., 2010). More recent research indicates that there is an improvement in the number of learners accessing tertiary education. However, a substantial gap still exists between the numbers who expect to study at tertiary level and those who do (Van Broekhuizen, Van der Berg & Hofmeyr, 2016).

The research questions addressed in this study evolved from the dual context of the weight of unfulfilled expectations of young people and South Africa's desperate attempts to build a healthy and vibrant economic environment. NEETs are a large untapped resource. The failure to assist them into further study or work has a collective impact on the psyche of our nation as the ambitions of our young people are continually thwarted (Cosser, 2009).

This observation resonates with my own field experience as expressed in the following field notes:

I am standing in front of the class of Grade 11 'repeaters.' I've been told that they are not expected to pass, they are a difficult class and that no one expects much from them. They ask me why I am doing this research and I explain that half of young people are not in employment or study. The class nod understandingly. I tell them that I am hoping to find ways we can ensure more young people get into jobs or tertiary study when they finish school. The class are still nodding. I tell them that I want to do something about all those young people sitting at home with nothing and the young people actually applaud! Some are standing and grinning. I have expressed the hopes and fears of their own hearts and the resonance is evident.

It is a sweet and spontaneous moment that still makes me tingle when I remember it.

Literature Review

Internationally, young people encounter obstacles when moving from school to further education and employment (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2000). Studies show that the youth have high educational expectations but that disadvantaged youth have the highest expectations (Kao & Thompson, 2003). Even in countries like Japan and Germany, which have previously been noted as promoting successful transitions, recent research shows an emerging group of NEETs, (Pilz, Schmidt-Altmann & Eswein, 2015). NEETs in these countries are less likely to have attained satisfactory academic grades in high school and less likely to have completed high school.

In Cape Town disadvantage is more often equated to the historical disadvantage imposed by apartheid and the ongoing inequity in financial resources that often affect Black African youth, (Swartz, 2009). However, the pattern of high expectations and unfulfilled plans is similar. Cape Town survey data suggested that only 18% of Black African students passed their matric with a Bachelor Passii despite high expectations of passing and going on to further study (Lam, Ardington & Leibbrandt, 2008). Bray et al. (2010) and Cosser (2009) noticed that while young people in all neighbourhoods have high expectations of going on to tertiary study, young people in poor or very poor Black African neighbourhoods were more likely to expect to study further than young people from Coloured neighbourhoods. In reality only 3.1% of Coloured and 3.2% of Black African young people participate in university education (Statistics South Africa, 2014).

Bray et al. (2010) and Swartz (2009) noticed that while high-status careers are sought after by both young people and their parents, there is a lack of specific knowledge about what exactly is required to achieve these high-status careers, particularly in the poorest Black African neighbourhoods. They seem to be more focused on being someone, in terms of career status, than on doing something (Swartz, 2009). Hence they might refer to being a doctor rather than helping sick people.

Various theories exist about why disadvantaged youth overreach in their education and career expectations. In an international comparative study Sikora and Saha (2007) found that in countries with the greatest inequality, young people are most likely to make ambitious tertiary study and career plans. They proposed that these plans represent knowledge of the surest route out of poverty, which disadvantaged young people see played out by their much more advantaged counterparts. This phenomenon, observed by the researchers in highly disparate economies, is described as "a revolution of rising expectations" (Sikora & Saha, 2007:72).

Yowell (2002) found that minority Latino youth in the United States of America (USA) had expectations for themselves that were far higher than real outcomes. All students in the study expressed a belief in education as the key to upward mobility and economic success. In addition, the majority of students believed that personal laziness was the main reason for possible failure, a sentiment echoed by young people in Swartz's Cape Town study (2009). No students in either study recognised that the school system, economic structure or limited opportunities within their community were possible obstacles to occupational success. Bray et al. (2010) note that disadvantaged youth rarely consider that obstacles to their goals might exist, or make contingency plans.

Oyserman (2013) has developed a theory to explain disparity in school outcomes despite common high achievement aspirations. Identity-based motivation (IBM) theory explains that there may be a gap between aspiration to a future self and action to achieve that outcome. Aspirations will only be acted upon if they come to mind at the right moment and the future outcome feels immediate and relevant in that particular moment (Lewis & Oyserman, 2015). Relevance is assessed by congruity with identity: do people like me have this possible future? This question refers to race, gender, culture, and social class. It is assessed by feeling connected to the strategies needed to enact the steps that will lead to the future outcome, like asking questions in class, reviewing previous exam papers during weekends, et cetera. Finally, the interpretation of difficulty is important. If a young person interprets difficulty as meaning that the task is impossible, they will not engage in the task. If they interpret it as meaning that the task is important and difficulty is to be expected on important tasks, then they are more likely to engage in the task (Oyserman, 2013).

In an American study entitled, "Unskilled and unaware of it," Kruger and Dunning (1999) report that people who underperform on a task are more likely to over-estimate their abilities. People with average or above-average abilities are more likely to rate themselves accurately. The results from this study have been replicated and the noted effect has been named the Dunning‑Kruger effect. Kruger and Dunning (1999) argue that people who underperform not only make mistakes, but they are unaware of their mistakes and make unfortunate choices as a result. Alexander, Entwisle and Bedinger (1994) found that students and parents who more accurately reported previous results were more likely to accurately predict future results.

I use the word "calibration" in this study to indicate how well learners' beliefs about their academic performance align to their actual performance and how realistic their confidence in their ability to improve is against comparative grade improvement data. Kruger and Dunning (1999) first coined the term "calibration" with regard to accuracy of self-assessment or ability to rate one's own performance. Practices of "self-regulated learning," first described by Zimmerman and Shunk (1989) and developed by Zuffianò, Alessaandri, Gerbino, Kanacri, Di Giunta, Milioni and Caprara (2013), appear to incorporate calibration. These practices include setting realistic goals against known baselines, developing specific learning strategies and reviewing achievements. In terms of IBM theory, they are the actions that lead to the desired future self (Oyserman, 2013).

The literature review points to the expectation that Cape Town youth have tertiary education ambitions that exceed likely outcomes based on current academic performance. The Dunning-Kruger effect tells us that the lowest performing learners are likely to report their performance as better than it really is. There are many theories about why underperforming learners report higher than actual performance and have corresponding overreaching achievement expectations. Their explanations of why they do this are likely to be similarly varied.

Methodology

In my 2015 study of Grade 11 learners' expected academic achievement and future plans, data was collected quantitatively and qualitatively. I employed a multi-stage sampling design in which I surveyed 813 Grade 11 learners from six high schools in Cape Town. Schools were selected based on the average matriculation bachelor pass performance for the province. School feesiii at these schools varied from free to a moderate cost of R12,500 per annum. All Grade 11 learners who attended school on the day of the survey were included. Learners who participated were aged from 15 to 19 years, of which 61% were female as one all-girls school was included in the sample. Due to the profile of low-cost, average-performance schools, very few White learners were included in the sample.

Quantitative Data

The survey was distributed electronically via tablets and was completed during school time. The survey contained 100 multiple-choice questions and three open-answer questions that could be completed in 20 to 40 minutes. Questions focused on intentions for post-school study or work as well as current study habits and confidence in academic ability. Learners were also asked to recount their most recent marks (i.e. Grade 11 term 2) and predict their final matric marks. Demographic information was also collected.

Actual Grade 11 term 2 results were obtained from four of the six participating high schools to provide a comparison between reported and actual results.iv Comparative Grade 11 term 2 and final matriculation results were obtained from a further two Cape Town high schools to provide an estimate of likely mark increases between these two time points. The two additional schools were selected as I was aware of the fact that they keept good records of results.

The survey was designed on SurveyCTO and the survey data was analysed in STATA using simple and multiple-regression analysis. The survey was based on previous surveys relevant to this piece of research (Cosser & Du Toit, 2002; James, 2000; Lam, Ardington, Branson, Case, Leibbrandt, Menendez, Seekings & Sparks, 2008).

Qualitative Data

During the school visits I took detailed field notes and conducted semi-structured interviews with available life orientation teachers at each school. Interviews lasted 20 to 40 minutes and topics covered were payment of school fees, matriculation completion rates, tertiary education access rates, and career guidance offered during life orientation lessons. Notes were taken during these interviews.

Following the survey I asked for volunteers to participate in further research. An effort was made for gender balance, with the final interview sample consisting of six females and four males.

Learners were interviewed during term 1 of Grade 12. Discussions lasted for 40 to 60 minutes for rounds 1 and 2. In both rounds the discussions took place at school or at a public mall, depending on what was more convenient for the interviewees. Notes were taken during the interviews and these were made available to the interviewees for their approval. For the first round of discussions I used a semi-structured interview with 5 topics: academic progress, the expected study and career future, family and community views on education, school choice, and hazards and obstacles to the expected future.

The second round of semi-structured interviews was conducted four to six months later, after the learners had received the results from their mid-year exams. All learners from the first round of interviews were invited to the second round, but only four agreed to participate. All were invited to bring their families but only one family agreed. Two life orientation teachers who had participated in the discussions at schools during the school visits were invited to participate in the second round of interviews. The selected teachers had shown the strongest interest in teaching career guidance and seemed most likely to offer insightful reflections on the findings from the research.

Teachers, family members, and learners were asked for their theories about why some young people reported their marks as higher than they really were. They were also asked what they thought would happen to young people with overreaching tertiary education expectations. The message of "you can be anything" was explored and learners were asked about the impact of participating in the study.

Qualitative data was analysed thematically using Braun and Clarke's method (2006). The documents generated from the interviews were coded for recurring patterns and themes.

In this paper I report on a portion of what was a much wider study completed for my Masters' degree. The focus of this paper is on learner reports of current academic achievement, expected matriculation results, and tertiary study expectations. Additional data not reported includes extensive field notes and observations from the school visits, career guidance content being taught in schools, career fields that interest young Cape Town learners, family and community views on education, tertiary institute preferences, actual post-school results and statistical modelling of the relationship between socio-economics, achievement and study ambitions.

Ethical Concerns

The University of Cape Town ethics committee cleared this study. Permission was granted by the Western Cape Education Department to work with the schools. The school principals also gave permission for the learners and teachers to participate in the study. Parental permission was not sought. All learners were at least 15 years old. At the start of the survey the learners consented electronically. Consent forms were read aloud and explained during the lesson. Four learners chose not to participate in the study and occupied themselves with other activities while the survey was completed. Learners who participated in discussions signed further consent forms clearly stating that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that they could also withdraw their data. One learner chose to do this. The one family that participated also signed a consent form and their right to withdraw was explained.

With regard to confidentiality, learners and family members who participated in discussions were given the option of using their real names or pseudonymns. Dineo and Anga proudly chose to use their real names, while other learners' names were changed. Schools were given number designations - School 1, School 2, and so on.

Results and Discussion - Aiming for Tertiary but Missing the Mark

In this section I report and discuss results in two main sections: In the first section I cover the inflated reports of academic achievement, how more realistic learners engage in self-regulated learning practices, and how less realistic learners engage in a kind of creative "photoshopping" of their memories to bring these in line with their own self-image. In the second section I cover expectations for final matriculation marks, self-belief as an explanation for over-reaching expectation, goal-setting, and the role of the message "you can be anything" in creating unrealistic expectations.

Inflated Reports of Academic Achievement

Learners in this study had high expectations of studying at tertiary level, with 87% indicating their intention to go on to study further after high school. Of those who planned to study further, 61% expected to study at university, 21% at a university of technology and 18% at a technical and vocational education and training (TVET) college. There were no significant differences in gender and study expectations. Most of these learners had reasonable knowledge of which institutions offered their preferred courses, how long the courses would take to complete, and which careers they would lead to.

Self-calibration, or the ability to recall marks accurately, and realistic predictions of final matriculation marks are critical when considering tertiary options. Put simply, a learner's current marks should be the baseline from which academic goals are set (Zuffianò et al., 2013). The final high school academic attainment directly impacts on entry pathways to tertiary institutions, with all tertiary courses having a minimum academic entry requirement.

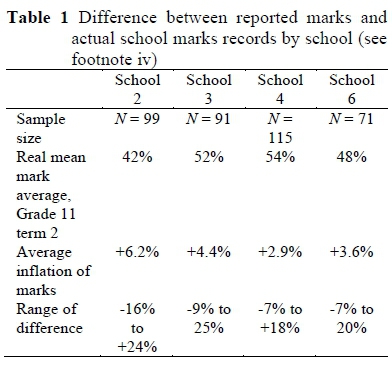

Learners at all schools inflated the record of their most recent marks (see Table 1). Some learners made very large errors, mostly in a positive direction. Seventeen per cent of learners reported that they were copying their marks into the survey rather than writing them from memory. Interestingly, there was no difference in the accuracy of those who said that they had copied the marks and those who said they had written from memory. Table 1 shows the difference between reported Grade 11 term 2 marks and actual school records at the four schools able to produce actual records.

Are learners unaware of their grades or are they deliberately mis-reporting? Learners were told that I would gain access to the actual results from their schools so there seemed to be little incentive to deliberately mis-report. Figure 1 shows that the better the learner's actual Grade 11 marks, the less likely they were to report inflated marks. Learners in the lowest quartile of performance were most likely to give inflated reports of their grades and this was true in each school and across the sample. In other words, underperforming learners do not know (or will not admit) their current marks and report that their performance is much better than it really is. They show poor self-calibration (Zuffianò et al., 2013). This is the same phenomenon reported by Kruger and Dunning (1999).

Self-regulated learning

Self-regulated learning practices was one of the themes noted during analysis of the interviews. Discussion participants Dineo and Esinako spoke about their self-regulated learning practices. These included a continued awareness of performance and checking for mark changes, or self-calibration (Zuffianò et al., 2013). Both were incredulous that people would mis-report their marks. They reacted similarly, with shock and laughter, then checked that they had heard correctly. Dineo and her mother offered the following explanation:

Dineo (Grade average 60%): We all twist the truth a little bit. I take my marks really seriously. I check them. I go back and check my progress.

Do you mean you carry a copy of your report so you can check?

Dineo: No, when I get home, I check with my report.

Dineo's mother: Every day they are coming from school and they sit down and I ask them, how did they go? How were their marks today? Ever since primary school they know I will ask them every day, how are they going.

Esinako also discussed the role of his mother in checking his marks. Even though his mother lives far away, in the Eastern Cape, when he goes to see her takes brings his report and they sit and discuss each subject. She knows which marks have gone up and which have not. Most recently she was unhappy with his 49% for Mathematics. "She had quite a lot to say about that!" Esinako told me.

Photoshopping marks

Some learners showed an astonishing difference between actual marks attained and reported marks. It seemed that they engaged in a kind of photoshopping. The process of photoshopping refers to electronically manipulating an actual photograph by cropping (cutting bits out), resizing, changing the colour, or changing the focus.

Underperforming learners photoshop their marks so that their recall represents what they believe they could have or can still achieve rather than what they did achieve. Justifications for this include that the results are incorrect, that the weightings for the various component tasks were unfair, or that the teacher was to blame. The remembered marks, then, are marks that have been filtered through stories (or lies) that excuse the learners from having to do anything to change their academic efforts.

When I told Esinako about the learners who mis-reported their marks, many by over 20%, he said:

Esinako (Grade average 69%): Wow, really? They need to be more realistic. They tell you the mark they'd like to have instead of the mark they do have.

How do you think it is going to affect them?

I think it's going to affect their future courses. They're going to apply for something they don't have the marks for. They aren't going to be accepted. Then it is going to be too late to re-apply.

Mrs Hendricks, a teacher at School 6, offered the suggestion that admitting to low marks will have consequences of needing to work harder in order to remedy the situation. Pretending to have good marks means that nothing needs to change. This is congruent with Yowell's (2002) findings that a lack of success among disadvantaged young people is attributed to laziness rather than systemic failure.

Mrs Hendricks: I wonder if they're in denial and they don't want to face reality. They're afraid of that reality because they know the consequences of not succeeding. They believe they can be anything, but they aren't doing anything towards it.

Mrs Marais at School 3 agreed that this pretending or lying was about avoiding responsibility for change.

Mrs Marais: This is about not wanting the mark, discarding the mark. Feeling ashamed. They lie to themselves. Ninety per cent of learners come from a mind-set of compromise. Any amount of lying can be justified for the right reason. 'There is still a tomorrow, I can fix it up.' Then they don't have to take accountability. They feel at ease. They don't have to fix it now. There is still next term.

Underachieving learners may in some way be aware of their actual performance and performance potential. However, this information does not fit with what they believe about themselves. If a young person's internal image is fragile, then protecting this fragile self-image may take priority over adjusting self-perceptions in line with reality. Indeed, some of the young people in this study lived in such difficult circumstances that photoshopping the reality of their life was the only way to have a robust and healthy psyche.

Oyserman (2013) offers an explanation with her Identity-Based Motivation theory. She explains that young people need to feel connected to both the idea of their future self and also the actions needed to reach that future self. The connection is created by a congruence with identity (I see myself as this sort of person) and also an immediacy of time (I need to take these steps now to reach my future self).

Keanu is a good example of IBM at work. He had mis-reported his own marks at 23% higher than they really were. I asked him about this.

Keanu (Grade average 43%): I would try to meet somewhere in the middle.

Do you mean the middle of what your marks were and what you hoped or thought they could really be?

Yes.

If I had seen you just after the survey and told you that I'd checked your marks and you had reported them at 23% higher than they really were, what would you have said?

I would have been so embarrassed.

Following that mid-Grade 11 report Keanu's parents had a long and serious talk with him about the consequence of his current disruptive behaviour in class and the actions that would need to be taken if he was to reach his dream of obtaining a bachelor pass in his matriculation final. This connected his future goal with an immediate need for action, (Oyserman, 2013). Keanu believed in his potential because he had prior experience of working hard and achieving high marks in primary school. This meant that the idea of hard work was relevant to his identity (Oyserman, 2013). His mid-Grade 12 report showed that his grade average had improved by an astonishing 20% in one year. Over time he was able to use the mark calibration practices he had already started to develop in primary school to take action towards achieving his desired future self.

Expectations for Matriculation Final Marks

The average expected matriculation final mark was 69%, an unlikely expected increase of 18% between mid-Grade 11 reported marks and the end of Grade 12. At all schools, learners expected to increase marks, however, at the schools with the lowest historical academic performance, these expectations were paradoxically the highest. Some learners expected astonishing increases of over 50%. Sikora and Saha (2007) might say that this is a micro example of their theory that those with the greatest disadvantage have expectations pushed upwards by the visible success of the more privileged. Table 2 shows the historic matriculation bachelor pass per school, the average expected mark increases per school and the standard deviation and range of these expected increases.

To ascertain how likely the expected mark increases were, data was collected from 50 students in two additional schools in Cape Town. Change in performance was measured from mid-Grade 11, 2014, to school leaving - end of Grade 12, 2015. This data formed a comparison for rating how realistic surveyed learners' predicted changes in performance were. The average change in this comparative sample was +4%, the range was -3% to +22% and the standard deviation was 5%. It is evident that all learners who expect a mark change of more than +22% are in the realm of wild imagination. This is particularly devastating for learners who require minimum tertiary entrance scores well beyond their current academic achievement.

In this study, schools with weaker academics produced more learners at risk of predicting an unachievable mark increase. In fact, low marks are a strong predictor of risky expectations of mark increases, just as they also predict inflated reporting of recent marks. Current marks correlated with expected change in marks at r = -0.12, p < 0.01.

Seven hundred and thirteen learners expressed an intention to study further. Seventy-five percent (533) of these did not have the minimum marks needed for entrance into the tertiary course of their choice in mid-Grade 11. The learners most at risk did not have the marks required and also had unrealistic expectations of mark improvements. Hence, they were making plans that they were very unlikely to be able to achieve.

Self-belief

Young people interviewed unanimously advocated for believing in yourself, dreaming big. This is congruent with Oyserman's (2013) theory that all people hold an idea of a successful future self. For some this dreaming big is demonstrated by high expectations. They believe these high expectations will bolster their academic performance. Other learners, while holding to the importance of self-belief and confidence, also talked of the importance of setting realistic, specific, achievable goals, and holding yourself accountable for doing the work needed to achieve these. These are the practices of self-calibration described by Zimmerman and Shunk (1989). The outcomes for the two groups of young people are likely to be startlingly different.

Anga, with an average in the high 40s, had the expectation of her marks improving by an unlikely 15%. She believed that confidence or even over-confidence played a vital role in success. "If you don't believe in yourself, no one else is going to do it for you!"

Anga (Grade average 46%): The real world is actually quite cruel and people will pull you down. If you get sucked into that you won't achieve. You need to tell yourself you can do it, no matter what someone tells you, no matter what your mark situation.

Boosting myself … unlocking my true potential … being confident enough to tell myself I can achieve. I used to fail isiXhosa but now I'm actually passing it. I told myself, 'I'm going to get 80%.' And then I see my marks come up into the 50s. It lies in you, what you do. Hard work, dedication, study, stay focused.

While there is a plethora of popular materials on self-belief, research shows that it contributes very little to overall academic achievement (Zuffianò et al., 2013). Zuffianò et al. (2013) show that previous academic achievement is the most significant predictor of future academic achievement.

Goal setting

The average expected matriculation final mark was close to 70% for all learners. It is almost as though there was an invisible line of respectability and achievement around this level of performance. For some this expectation was related to wanting to secure a place at a tertiary institution, but for others it was due to wanting to be seen as an achiever. This resonates with the findings by Bray et al. (2010) and Swartz (2009) in their Cape Town-based ethnographic research. Both observed that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds were more focused on the status of having a professional career than on how they would achieve that goal.

Some learners set their matric goal based on their belief in their ability and others based on the minimum entry requirements for the desired tertiary course.

Keisha (Grade average 48%): I'm expecting 75% plus. That is my goal.

Why 75?

Because that is the mark I need to get into university - either UCT or UWC.vi

Nangamso expresses some of the complexity of goal setting based on aspirations rather than on the real possibility of achievement. Nangamso plans to go to UCT but with an average of only 55% in mid‑Grade 11 the chance of this is poor. She attributes success to having dreams and working hard. While she acknowledges that not everyone has the capacity to study at tertiary level, she does not seem to consider that this might include her. Consistent with Yowell's (2002) findings she blames the laziness of those who don't succeed and does not consider a lack of systemic support or complications of poverty.

Do you think you have high expectations?

Nangamso (Grade average 55%): Yes, I expect those marks because I need them. I really want to get into UCT. It is my dream.

So your goal of going to UCT causes you to expect you will get these marks?

Yes, because those are the marks I need.

What do you think about those who don't pass matric?

They didn't set goals for themselves, didn't work hard towards those goals, didn't work as hard. … We can't all go to tertiary. We don't have the same capacities. We don't have the same goals.

In the full sample, 90% of young people's actual Grade 11 marks average was less than 65%, putting them out of range for most university courses in the Western Cape. While young people in this study realised that not everyone could enrol at a tertiary institution, they mostly did not consider that they were individually at risk of not succeeding. This is in line with Sikora and Saha's (2007) analysis, which indicates that the youth in the most disadvantaged and unequal countries have the highest expectations of proceeding to tertiary education. Hence, in developing economies young people are at greatest risk of having unfulfilled expectations.

You can be anything

I told Dineo's family that I have often heard the message "you can be anything" conveyed to young people. I had heard the minister for Social Development give this message twice in the past month to halls full of teenagers from disadvantaged backgrounds. I asked Dineo what she thought of this message and she offered surprising insight.

Dineo: The ideal is - you can be anything, go for anything. It's the ideal. But in the townships there are so many challenges that hold you back. People like me, Black, females … when they reach a goal, you know how valuable it is because you know where you came from, and the struggles you had. But those challenges shouldn't be there. The challenges with sanitation and stuff.

A teacher from School 5, Mrs Hendricks, stated that she actively encouraged the learners to believe that there are tertiary options for everyone even though she knows that some end up working in local shopping centres. While she estimated that 35 to 40% of learners in Grade 12 would finish with averages under 40%, she also believed that post‑school study options existed for everyone. She generally agreed with the message "you can be anything" but cited laziness and a lack of goal setting as the reason that learners did not achieve.

Esinako did not see poverty or disadvantage as an excuse to underachieve. He said that he believed that learning resources were available equally to all - internet, television (TV), and online textbooks. Keanu agreed, indicating that the school system offered the same building blocks to all and it was up to each person what he or she did with them. Both Esinako and Keanu cited the story of the one who succeeded against the odds as evidence that all can succeed against the odds.

Esinako: You can't let your circumstances determine your future. People make excuses to cover for their lazy ways. Everyone has challenges but they choose if they will be a success. We have a lot of people come from impoverished backgrounds who are success stories. There is a story about a young black South African guy who went into mining and now he's a billionaire.

Some young people interviewed perceived that "you can be anything" was only true if it was linked to opportunity and resources and that distribution of these was not equal. Other young people had bought into the narrative and believed that the education system was an equaliser with all young people getting essentially the same building blocks. Although they admitted to potential learning hazards like big classes and poor discipline, these young people felt that these hazards should not become excuses to not achieve. Swartz in South Africa (2009) and Yowell in the USA (2002) similarly found that disadvantaged youth believed that laziness was the reason for possible failure with none identifying problems in the school system, economic structure or limited opportunities in their community. This can only lead the most vulnerable young people in developing economies to attribute their lack of academic success to personal attributes, robbing them of the hope and courage needed to succeed in a repressed labour market.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Eighty-seven per cent of Grade 11 learners in this study had expectations of going on to tertiary study. Seventy-five per cent of those did not have the marks needed to meet minimum entry requirements for their preferred courses. Learners in the lower performance quartiles were more likely to inflate their reports of recent marks and also to have unrealistically high expectations of their final matriculation results. This unawareness of recent performance means that they did not have a performance baseline from which to set goals or measure achievement. The unrealistic expectations of final marks put them at risk of applying to tertiary courses that they were unlikely to be able to access. Two key recommendations following from this research are discussed in the next section.

Promote Self-Regulated Learning

Learners in this study who were most able to accurately report their marks (or best calibrated) were also the highest performing learners. These learners described processes of self-regulated learning. They were aware of and continually referred to their recent marks. Their parents were also aware of their recent marks and were continually checking current performance. They set realistic goals based on current performance, developed strategies, and reviewed progress. These findings are congruent with the self-regulated learning strategies described by Zuffianò et al. (2013).

Believing in the ability to improve is not the same as believing that you can be anything. Learners most at risk from the lie that you can be anything are those who do not engage with actual hard work, goal setting, and strategising. They are convinced that their self-belief alone can make a dream reality. They hold a desirable view of their future self but fail to take the actions that will lead to the future becoming a reality (Oyserman, 2013). This incongruity between their actions and plans leads them to photoshop memories of their marks. They mis-report them as the marks they think they should have obtained. They adjust their truth to avoid taking responsibility for poor performance.

Young people need to be explicitly taught to make the link between academic performance and tertiary entrance. Current academic performance is the best indicator of future academic performance (Van Broekhuizen et al., 2016). There are challenges for young people in understanding university and course entrance criterion. In the Western Cape each institute has its own individual, and sometimes complex, admission points calculations. This makes it difficult for young people to set realistic achievement goals. Teachers need to be knowledgeable to guide young people, and also to check that plans are likely to be attainable.

Young people can be taught to apply goal setting to academic performance with personal academic reviews taking place each quarter as reports are released. The teacher can ask: "Did you reach your goals for this term? What strategies did you try? What are your goals for next term? How will you achieve this?"

Stop Telling Young People they can be Anything

The self-belief narrative, "You can be anything!," is communicated in schools, by communities, in homes, in classrooms and by politicians. This lie is attractive in the face of desperate poverty. Stories of the one who succeeded against the odds are cited as evidence. The beautiful wealth just over the fence from township poverty leads to an understandable development of expectations, however, the educational and economic enablers that could lead to a realisation of these dreams are not able to keep up. In line with the findings of Sikora and Saha (2007) inequality boosts expectations and young people in the poorest and most unequal countries are most likely to be unfulfilled.

Changing this community narrative is possibly the biggest challenge ahead of us. During the course of this study I heard it spoken by learners, teachers, parents, and politicians. These were all people who genuinely wanted the best for young people growing out of struggling backgrounds. They aimed to encourage. However, what they offered was hope with no substance. Bray et al. (2010) found that belief in studying at tertiary level and not the actual doing so, persisted for years after finishing school. When the research team questioned young people and parents about what it was like to hold this belief in the face of a very different reality, some participants started to cry. The team decided that it was unethical to continue that line of questioning (J Seekings, pers. comm.).

We need to be realistic about the tertiary study and labour market opportunities that are available and take greater care to prepare young people for these options.

Notes

i . The racial categories in this paper are commonly used by the Western Cape Education Department to monitor progress towards racial equity. Learners in this study self-designated their own race.

ii . The Grade 12 matriculation certificate has three pass levels. A B pass is the minimum requirement for continuing on to study a bachelor degree.

iii . Western Cape Department of Education data, analysed by SAILI (2014).

iv . School 5 did not respond to the request for records and School 1 had lost their records in a fire.

v . Based on 2013 school performance data publically available through Western Cape Education Department and analysed by SAILI (2014).

vi . UCT - University of Cape Town, UWC - University of the Western Cape.

vii . Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alexander KL, Entwisle DR & Bedinger SD 1994. When expectations work: Race and socioeconomic differences in school performance. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(4):283-299. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787156 [ Links ]

Branson N, Lam D & Zuze L 2012. Education: Analysis of the NIDS Wave 1 and 2 datasets (South African Labour and Development Research Unit Working Paper 81). Cape Town, South Africa: Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

Bray R, Gooskens I, Kahn L, Moses S & Seekings J 2010. Growing up in the new South Africa: Childhood and adolescence in post-apartheid Cape Town. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Press. [ Links ]

Cosser M 2009. Studying ambitions: Pathways from Grade 12 and the factors that shape them. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Press. [ Links ]

Cosser MC & Du Toit JL 2002. From school to higher education?: Factors affecting the choices of grade 12 learners. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2003. National Curriculum Statement (NCS) Grades 10-12: Life Orientation. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. [ Links ]

James R 2000. Socioeconomic background and higher education participation: An analysis of school students' aspirations and expectations. Canberra, Australia: Department of Education, Science and Training. Available at https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A2433. Accessed 11 July 2019. [ Links ]

Kao G & Thompson JS 2003. Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 29:417-442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100019 [ Links ]

Kruger J & Dunning D 1999. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognising one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Psychology, 77(6):1121-1134. [ Links ]

Lam D, Ardington C, Branson N, Case A, Leibbrandt M, Menendez A, Seekings J & Sparks M 2008. The Cape Area Panel Study: A very short introduction to the Integrated Waves 1-2-3-4 (2002-2006) data. Cape Town, South Africa: The University of Cape Town. Available at http://www.caps.uct.ac.za/resources/caps1234_introduction_v0810.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019. [ Links ]

Lam D, Ardington C & Leibbrandt M 2008. Schooling as a lottery: Racial differences in school advancement in urban South Africa (Working Paper Series Number 18). Cape Town, South Africa: South Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town. Available at http://www.opensaldru.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11090/36/2008_18.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 12 July 2019. [ Links ]

Lewis NA Jr & Oyserman D 2015. When does the future begin? Time metrics matter, connecting present and future selves. Psychological Science, 26(6):816-825. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0956797615572231 [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2000. From initial education to working life: Making transitions work. Paris, France: Author. [ Links ]

Oyserman D 2013. Not just any path: Implications of identity-based motivation for disparities in school outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 33:179-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.09.002 [ Links ]

Pilz M, Schmidt-Altmann K & Eswein M 2015. Problematic transitions from school to employment: Freeters and NEETs in Japan and Germany. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(1):70-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.835193 [ Links ]

SAILI 2014. Choosing a high school in the Western Cape. Available at http://saili.org.za/website/choosing-a-high-school/. Accessed 10 June 2017. [ Links ]

Sikora J & Saha LJ 2007. Corrosive inequality? Structural determinants of educational and occupational expectations in comparative perspective. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 8(3):57-78. Available at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ/article/view/6820/7460. Accessed 5 July 2019. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2014. General household survey 2013. Pretoria: Author. Available at http://beta2.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182013.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2019. [ Links ]

Swartz S 2009. Ikasi: The moral ecology of South Africa's township youth. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Van Broekhuizen H, Van der Berg S & Hofmeyr H 2016. Higher education access and outcomes for the 2008 national matric cohort (Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: 16/16). Stellenbosch, South Africa: Department of Economics & Bureau for Economic Research, Stellenbosch University. Available at https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Van-Broekhuizen-et-al.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2019. [ Links ]

Yowell CM 2002. Dreams of the future: The pursuit of education and career possible selves among ninth grade Latino youth. Applied Developmental Science, 6(2):62-72. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0602_2 [ Links ]

Zimmerman BJ & Schunk DH (eds.) 1989. Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [ Links ]

Zuffianò A, Alessaandri G, Gerbino M, Kanacri BPL, Di Giunta L, Milioni M & Caprara GV 2013. Academic achievement: The unique contribution of self-efficacy beliefs in self-regulated learning beyond intelligence, personality traits, and self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 23:158-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.07.010 [ Links ]

Received: 23 June 2017

Revised: 28 March 2019

Accepted: 30 May 2019

Published: 30 September 2019