Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 n.2 Pretoria May. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1323

ARTICLES

WhatsApp: Creating a virtual teacher community for supporting and monitoring after a professional development programme

Maglin Moodley

Department of Science and Technology Education (SciTechEd), Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. maglinm@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The introduction and use of online social media networks in education has provided a variety of unique methodologies in support of teaching, learning, and knowledge gathering. The presence of these networks has created opportunities to hear the voice of the teacher. This study explores how teachers and officials from a rural district in South Africa used the WhatsApp platform as a virtual community of practice to aid in monitoring and support after attending a professional development programme. The data used in this study was collected from the WhatsApp conversations held amongst teachers and officials. This data was analysed within the conceptual framework of social learning and social networking. The findings derived from this study show that the effective use of an online social media network to support a virtual community of practice is dependent on the participants' awareness of the context within which the community exists and the willingness of the participants to accept differing views and opinions.

Keywords: community of practice; Millennium Development Goals; social learning; social media; social networking; teacher professional development; virtual community of practice; WhatsApp

Introduction

In a developing world, education is instrumental in alleviating poverty. In 2002, the United Nations published the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to support developing countries in achieving parity with developed countries. The second of the eight MDGs was aimed at ensuring universal primary education for all by providing access to quality education. Information Communication Technology (ICT) has been identified as a key enabler to accelerate the realisation of the MDGs (Christie, 2008). However, in the South African context, ICT alone will not guarantee a quality education system. According to Moloi, Gravett and Petersen (2009), a quality education system requires a teaching force that possesses the appropriate knowledge and skills essential in the digital age.

Securing such a teaching force depends on the effectiveness of the teacher professional development (TPD) programmes offered to the teachers (Shohel & Banks, 2012). A successful programme is not purely about attendance, but is also dependent on the post-TPD monitoring and support teachers receive (Niess, 2011). Post-TPD monitoring and support can be hindered by factors that include workload, time constraints and distance between teachers and officials. Could these hindrances be reversed with technology?

The introduction of Web 2.0 technology saw a transition from inert web platforms to more dynamic platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and WhatsApp. Web 2.0 supports greater user interactivity and collaboration with improved communication channels (Owen, Grant, Sayers & Facer, 2006). These platforms allow users to form like-minded online communities, while issues of distance and time are negated.

Background

In 2013, the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) developed the Teacher Assessment Resource for Monitoring and Improving Instruction in the Foundation Phasei software (TARMIIfp). The software consisted of a bank of assessment items that are aligned to the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS).ii The aim of the TARMIIfp study was to determine if use of the software by the teachers would influence learner performance in literacy.

The study was implemented in the Limpopo, Free State, North West (NW) and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa, and comprised two components. The first was the TPD programme that teachers attended; the second was the school-based monitoring and support provided to the teachers who attended the TPD. The TPD training programme consisted of two modules: the first module focused on assessment in the Foundation Phase; the second focused on use of the TARMIIfp software. As part of the research design, training, monitoring and support of teachers was facilitated by the e-learning and curriculum officials of the district office.

In this paper, the focus will be on the North West Province. The North West Province is predominately rural with a few urban centres. It comprises four education districts, with each district being divided into circuits. The TARMIIfp study was conducted in circuits East and Westiii in District B.

Nature of Problem

Teachers who attended the TPD programme were supposed to receive a series of school-based monitoring and support visits conducted by the NW officials. The ICT based training programme attended by teachers was successful. However, initiating and sustaining the monitoring and support component was problematic. This was due to the fact that officials had to travel vast distances to monitor and support individual teachers. As a result, only few teachers were monitored and supported in the first month. Teachers who were initially excited about using the software now felt isolated, with no support from the officials. In an attempt to address this problem, the teachers and officials from District B created a WhatsApp group, the formation of which was not part of the TARMIIfp research design, but proved critical in the context of the problem.

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this paper was to explore how teachers and officials from a rural North West district used WhatsApp as a platform to create a virtual community of practice to serve as a monitoring and support platform after attending a professional development programme.

Literature Review

Advancements in technology have brought changes in how people interact, communicate and learn (McLoughlin & Lee, 2008). However, education has been slow to embrace technology for teaching and learning (Lautenbach, 2011).

Teacher professional development in the 21st century

To achieve universal primary education, it is essential that teachers acquire the relevant content knowledge, technological skills and pedagogical knowledge (Mamba & Isabirye, 2015; Shohel & Banks, 2012). However, Buczynski and Hansen (2010) and Jita and Mokhele (2014) conclude that in order for teachers to acquire these competencies, they need to attend intensive TPD programmes.

The traditional approach to TPD, which saw in-service teachers attending training, will not, in itself, improve teacher competencies (Steyn, 2011). For change to take place, Niess (2011) and Smylie (2014) suggest that TPD programmes ought to comprise subject-specific training, followed by continuous monitoring and support after the training event. Conducting monitoring and support is not easy, as it is often hampered by issues of teacher workload, time, and distance between teachers and officials. However, Schlager and Fusco (2003) recognise that post-training support can be addressed using collaborative teacher communities. This view is supported by Smylie (2014), who suggests that these communities would also promote collaborative learning. However, Luft and Hewson (2014), as well as Mestry, Hendricks and Bisschoff (2009), argue that in order for collaborative learning to take place, teachers within these communities must provide and receive immediate support from peers. So, within a rural context like the NW Province, geographically dispersed teachers will still encounter a challenge in receiving immediate support and feedback from the community (Coto & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2008).

With the growth of social media, real-time communication and collaboration within a community is now a reality (Amry, 2014; Roman & Wertlen, 2008). Social media can be used to support and monitor teachers and officials through the formation of online communities of practice (CoP) (Luft & Hewson, 2014; Mushayikwa, 2013).

Communities of practice in the 21st century

A CoP is an assembly of individuals who come together to engage regarding a common concern, so as to improve or solve a given situation (Coto & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2008; Jita & Mokhele, 2014). According to Wenger (2011), a CoP has three elements, viz.: domain, identifying the common interest of the group; community, including members of the group who participate in activities and discussions regarding the domain; and practice, referring to the group of individuals in the domain who are practitioners or specialists.

Within the education space, teachers regularly encounter common problems and concerns. Little (2003) posits that teachers can work collectively to address these problems, and support one another's professional growth. With the advancement in technology, can technological advancements be used to transform a CoP?

With the introduction of Web 2.0 technology, web platforms have become more dynamic, and this has led to the growth of virtual communities of practice (VCoP) (Gülbahar, 2014; Susilo, 2014; Vanwynsberghe & Verdegem, 2013). A VCoP uses social media to support online community interaction, collaboration and learning (Malecela, 2016). The benefit of an education VCoP, as suggested by Aburezeq and Ishtaiwa (2013) and Wenger (2011), includes providing teachers and officials with a platform to air their concerns and receive real-time support.

According to Surowiecki (2004), a VCoP is a platform for the wisdom of crowds, and it is through these communities that teachers can create collective intelligence and promote the generation of new, fresher, richer, and more sophisticated ideas in support of teaching and learning (Jita & Mokhele, 2014; McLoughlin & Lee, 2008). The growing use of VCoPs is supported by the expansion of social media, and this could have positive implications for teaching and learning (Yang, 2009).

WhatsApp as a social media platform

The past two decades have seen growth in the use of social media platforms (SMP) for social interaction, trade, commerce, technology, and medicine (Van Weert, 2006; Yeboah & Ewur, 2014). In education, key players have been hesitant to embrace SMPs for supporting teaching and learning (Sayan, 2016). Malecela (2016) stresses that SMPs can assist teachers to form VCoPs that could support teaching and learning. This view is supported by Sayan (2016), who explains that SMPs like WhatsApp could help to support collaborative information discovery, collaborative learning, and knowledge sharing by teachers.

As at February 2017, WhatsApp was the second most widely used SMP, with 1.2 billion users, while Facebook lead with 1.9 billion users (Sparks, 2017). WhatsApp is an instant messaging (IM) application that allows users to exchange text or multimedia messages with contacts (Kharade, 2016). The lure behind WhatsApp lies in its ease of use and compatibility with most digital devices and operating systems (Kharade, 2016; Sparks, 2017).

The versatility of WhatsApp lies in its ability to create groups and then allows the sharing of text messages, chats, images, audio, video, and web links within the group (Bouhnik & Deshen, 2014; Sayan, 2016). In a digital world, where ubiquitous computing and demand-driven learning are the norm, it is crucial for all members to become active participants and co-producers of content and learning processes, rather than mere recipients (McLoughlin & Lee, 2008).

Conceptual Framework

The introduction and use of the WhatsApp platform as a VCoP by teachers and officials was not part of the study design, but occurred as a result of the monitoring and support component of the study. A VCoP is shaped by two streams: the first stream relates to social networking within the community, and the second relates to learning within a social structure.

A conceptual framework helps guide the analysis of collected data, which supports know-ledge generation and an understanding of the concept or concepts under study (Ndlovu & Hanekom, 2014). The suggested framework for this paper embraces the two streams of a VCoP by integrating Gunawardena's Social Networking Spiral (SNS) and Wenger's Social Discipline of Learning (SDL).

The conceptual framework shown in Figure 1 comprises three aspects: (1) the Social Media Wheel; (2) the SNS; and (3) the SDL. This framework will be used to support and explain conversation extracts taken from the NW WhatsApp VCoP.

Social media wheel

The benefits of the WhatsApp platform was central to the NW online community choosing it to sustain the school-based monitoring and support component. The WhatsApp platform comprises of four key functions, these include: instant mess-aging, picture sharing, file sharing and video file sharing.

The social networking spiral and the social discipline of learning

The next part of the framework fuses the SDL phase with the SNS stage.

Phase 1: Learning partnerships

A VCoP learning partnership is built on recognition, engagement and negotiation between members of the community. The learning part-nership in the community is dependent on the context and discourse of the community (Wenger, 1998).

Context: This is the unique contextual experience, knowledge and insight that individual members bring to the VCoP, which, in itself, exists in a specific context.

Discourse: Individual members of the VCoP assimilate their unique experience, insight and knowledge through discussion, agreement or disagreement.

These interactions in the VCoP lead to the formation and acceptance of a state of negotiated meaning by the community (Gunawardena, Hermans, Sanchez, Richmond, Bohley & Tuttle, 2009).

Phase 2: Learning governance

The process of learning governance occurs when members seek mutual agreement and alignment regarding common problems and concerns that confront the community (Wenger, 1998). Action must be taken by members to reach mutual understanding of the problem, which allows members to reflect on their perceived views.

Action: Members use the online community to address and solve common problems through collective action and intelligence.

Reflection: The convergent and divergent views of members are heard and reflected upon, which may result in a change in attitude or understanding at an individual or group level (Gunawardena et al., 2009).

Phase 3: Accountability and learning citizenship

To ensure that learning occurs in the community, it is imperative that members respect and accept individuality and accountability as individuals within the community. Reorganisation and socially mediated metacognition in the group must occur in order for learning to take place.

Reorganisation: Individual members explore the reasoning and views of peers, which leads to de-construction followed by re-construction of ideas and knowledge of common concern.

Socially Mediated Metacognition: Individual members of the community offer their thoughts for scrutiny and critiquing, so as to reach a state of mediated and negotiated understanding.

From this point onwards, the NW TARMIIfp WhatsApp group will be referred to as the VCoP.

Methodology

Approach to Inquiry

As the VCoP was not part of the research design, no data collection instruments were developed. As a result, the conversations that occurred in the VCoP became the primary source of data for this paper. The conversations were extracted using the WhatsApp email export facility. The issue of ethics concerning the use of these conversations was resolved, as teachers and officials signed an official consent form, which gave the research team consent to use all conversations on condition that the anonymity of individuals and schools was ensured.

Participants

In the NW study, the schools were sampled and not the teachers. The sample consisted of 20 primary schools and three volunteer Foundation Phase teachers per school. Of the 60 teachers who formed the NW study group, only 18 opted to join the VCoP; two district officials also joined. As alluded to earlier, the formation of the VCoP was not part of the study design, and therefore the teachers joined the community of their own free will. As a result, the number of teachers was not constant, but varied during the course of the study. Towards the end of the study, there were 11 teachers in the VCoP, which meant that seven teachers left the VCoP.

Data Collection

The data used in this paper was extracted from the teachers' VCoP (WhatsApp) conversations. These conversations were exported into MS Word, saved on the HSRC's secured shared drive and backed up on an external drive.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis is a flexible and useful qualitative research tool that provided a rich and detailed account of the conversations extracted from the VCoP (Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bondas, 2013). The extracted MS Word text was exported into NVivo 10, a qualitative data analysis software tool. The analysis of the data was guided by the Braun and Clarke (2006) Six Steps of Thematic Analysis method, i.e.:

· Familiarising with the data - required a thorough understanding of the VCoP conversations and the context.

· Generating initial codes - multiple codes were generated based on important aspects of the conversations. This led to the formation of broad themes.

· Searching for themes - relevant extracts from the conversations were combined or split, which resulted in broad themes being determined.

· Reviewing themes - the broad themes were then combined, refined, separated, or discarded, which led to new concise themes that overlapped with the phases and stages of the conceptual framework.

· Defining and naming themes - the revised themes were then assigned names, as per the conceptual framework.

· Producing the report - the final stage used the various extracts by relating these to the themes and literature. The narrative relayed the findings of the textual analysis and was more than a description of the themes.

Findings

The findings of the study are presented against the phases of the Social Discipline of Learning model (SDL).

Phase 1: Formation of Learning Partnerships in the WhatsApp Community

Context of the community

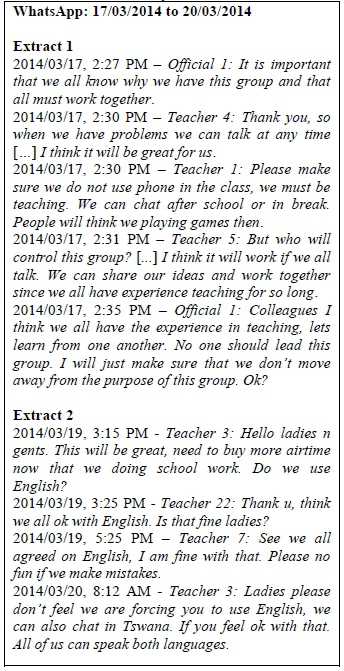

The context in which members of the VCoP interact is central to an effective learning part-nership. The finding around the issue of context is clearly evident in extracts 1 and 2. In Extract 1, the issue of context relates to the work environment. Teacher 4 appreciates the flexibility of communicating on WhatsApp, but is reminded by Teacher 1 that they cannot interact and converse during teaching contact time. In Extract 2, the issue of language comes to the fore, especially the use of indigenous African languages within the VCoP. The community accepts to use English over Tswana. However, Teacher 7 showed some apprehension about using English as it is not her first language. However Teacher 3 suggests that colleagues should be free to use either English or Tswana. Although the teachers opted to use English over Tswana, the apprehension shown by Teacher 7 brings to the fore the question of the use of an indigenous language in the digital space, and whether this issue contributed to the withdrawal of the seven teachers from the VCoP. This inference is inconclusive, opening up the opportunity for further research.

Discourse within the community

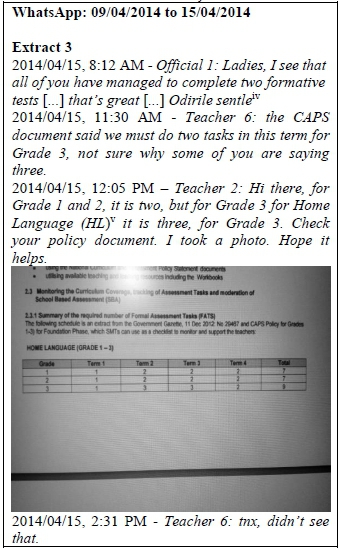

In any online learning partnership, it is important that the discourse in the VCoP accommodates the diverse views and perceptions of members so that a common opinion or solution is reached. Extract 3 provides a good example of how teachers used the process of discourse to clarify varying and contradictory views and perceptions regarding the number of required assessments per term, as specified by the CAPS policy. To support the discourse, Teacher 2 shared an image of a CAPS policy item to support the official policy requirements.

Phase 2: Achieving Learning Governance in a WhatsApp Community

Action within learning governance

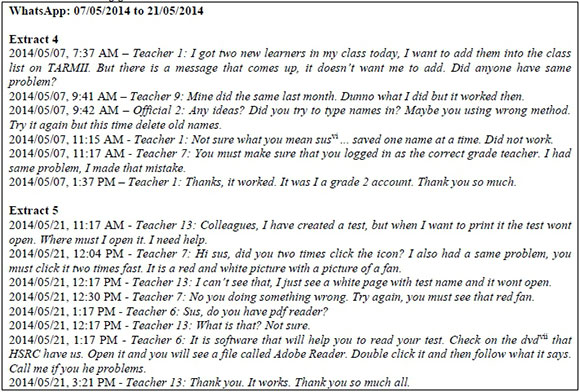

With the formation of the VCoP, members need to address common problems or concerns through a collective approach that results in specific and deliberate discourse and action. In Extract 4, Teacher 1 experiences a problem with adding new learners onto her existing class list. Teacher 9, Official 2 and Teacher 7 attempt to assist by suggesting possible action that could be taken. Teacher 7 then acknowledges that she made the same error earlier and suggests a simple solution. Later in the day, Teacher 1 reports back to confirm having overcome the issue. In Extract 5 we see that Teacher 13 is not able to print the PDF version of the test. Teachers 7 and 6 both offer assistance. Teacher 6 starts off by trying to locate the error and then leads Teacher 13 to the solution, which is found on the software installer DVD. Both Extract 4 and 5 show how the teachers, as a collective of the VCoP, assisted with solving problem.

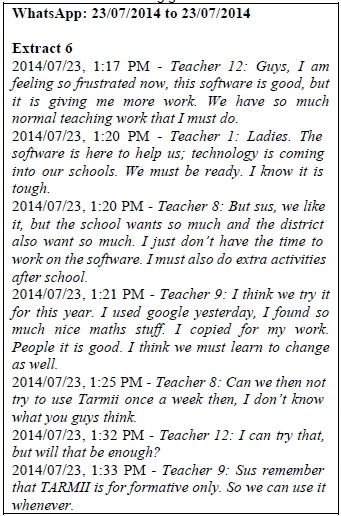

As members have divergent views regarding a problem or concern, reflection is needed at group level so that attitudes and understanding can be adapted. In Extract 6, two groups of teachers with differing perspectives on ICT are in conversation. Teachers 8 and 12 claim that although they like the software, it is creating more work for them. On the other hand, Teachers 1 and 9 seem to be pro-technology and try to argue the value of ICT, especially TARMIIfp in teaching. In the course of the conversation, Teacher 8 indicates that she will try to use it at least once a week. Teacher 9 then reminds the group that the software does not have to be used daily, since it is a formative assessment tool and can be used when applicable.

Reflection within learning governance

Phase 3: Learning Citizenship in a WhatsApp Community

Reorganisation of learning

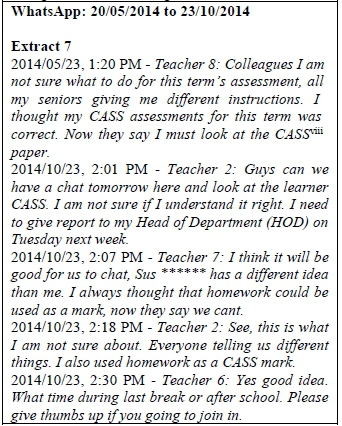

Members of the VCoP need to re-construct shared ideas and knowledge and ultimately reorganise these as a collective community understanding of the problem or concern. In Extract 7, teachers discuss their concern regarding the use of CASS. CASS is the strategy of continuous assessment of learners. The point of dispute raised by Teacher 8 is whether or not the CASS framework recognises homework as a form of assessment. Teachers 2 and 7 share the concerns of Teacher 8 regarding the mixed messages they are getting from their advisors. As a collective, the teachers of the VCoP suggest a virtual meeting on the WhatsApp platform to try to address the confusion that exists in the group.

Socially mediated meta-cognition within a WhatsApp community

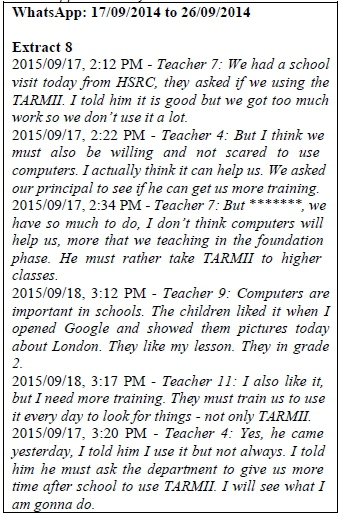

In the final stage of social networking, it is important that members of the VCoP share their thoughts and perceptions regarding a problem or concern so that the community can argue and critique their views. In Extract 8, Teacher 4 questions the practicality of technology and more specifically TARMIIfp for teaching and learning in the Foundation Phase. This view is challenged by Teachers 7, 9 and 11, who argue the benefits of technology in education. Teacher 9 then gives an example of how she used Google to expose her learners to a topic and that the learners were in Grade Two.

Discussion

According to Gon and Rawekar (2017), social media platforms like WhatsApp can play a critical role to support teaching and learning in an online community. The findings from the current study emphasise the role played by contextual factors in the formation of a VCoP and the readiness and willingness of the VCoP to accept and support varying views and opinions so as to reach a state of collective action, understanding, and learning.

These findings were reinforced in the early work of Aburezeq and Ishtaiwa (2013) and Ndlovu and Hanekom (2014), who acknowledged that active participation in a WhatsApp community is decidedly dependent on and influenced by the process of monitoring and support amongst the community members. Amry (2014) further suggested that the active participation within a WhatsApp community can lead to increased motivation and collaborative learning amongst members of the online community.

Preceding studies on the use of the WhatsApp platform in education essentially reflected on the relationship between teacher and student (Aburezeq & Ishtaiwa, 2013; Amry, 2014; Gon & Rawekar, 2017; Ndlovu & Hanekom, 2014). On the other hand, the current WhatsApp study used the lens of social learning and social networking to explain the relationship between teachers and officials for the purpose of monitoring and support after a TPD programme. The findings from this study can, in the future, serve to support the use of social media (WhatsApp) in TPD programmes, as well as the creation of VCoPs to help sustain the monitoring and support component.

The findings from this study created opportunities for possible further in-depth research in:

1. the use of the social media to promote professional development of teachers in rural areas;

2. the use of WhatsApp as a platform to initiate and sustain monitoring and support of teachers by education officials; and

3. the role social media platforms play in the use and promotion of Indigenous African languages in the digital space.

Conclusion

The 21st century has seen many demands being placed on the South African teacher, of which teaching and preparing learners to live and work in this century is central. To achieve this end requires the teacher to be competent in both the subject content as well as pedagogical methods appropriate to the 21st century (Wetzel, Zambo & Buss 2000). In an effort to achieve this level of competency, TPD programmes aimed at empowering South African teachers with the necessary 21st century knowledge and skills have become the norm in teacher development (Jita & Mokhele, 2014; Mestry et al., 2009; Steyn, 2011). However, research shows that in order for teachers to preserve and use the knowledge and skills acquired during the TPD programmes, post training monitoring and support becomes essential (Buczynski & Hansen, 2010; Coto & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2008).

This paper reported on how a small group of teachers and education officials from a rural district in the NW province of South Africa utilised the WhatsApp platform to serve as a VCoP to sustain the monitoring and support component of the TARMIIfp TPD programme. The findings from the study showed how teachers and officials effectively used the WhatsApp platform to address and resolve problems and misunderstanding around the soft-ware as well as curriculum and assessment related matters. What the findings emphasised is that in order for the platform to sustain and promote monitoring and support in a VCoP, it was essential that members of the VCoP must understand and appreciate the importance of the context of the community as well as the diverse views and opinions of the community.

Notes

i. Foundation Phase refers to Grade 1, 2 and 3 of the South African education system.

ii. CAPS: This is the official education curriculum of South African schools.

iii. Pseudonyms are used in place of the actual District and Circuit names.

iv. Tswana for "Well done!"

v. HL: Refers to the language, or languages, spoken by a learner at home, hence Home Language.

vi. Sus: Term of endearment used amongst female South Africans. The literal translation is sister.

vii. dvd: Stands for "Digital Versatile Disc," a type of optical media used for storing digital data.

viii. Continuous assessment (CASS) is part of the South African assessment policy.

ix. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Aburezeq IM & Ishtaiwa FF 2013. The impact of WhatsApp on interaction in an Arabic language teaching course. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 6(3):165-180. Available at http://universitypublications.net/ijas/0603/pdf/F3N281.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2019. [ Links ]

Amry AB 2014. The impact of WhatsApp mobile social learning on the achievement and attitudes of female students compared with face to face learning in the classroom. European Scientific Journal, 10(22):116-136. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2014.v10n22p%25p [ Links ]

Bouhnik D & Deshen M 2014. WhatsApp goes to school: Mobile instant messaging between teachers and students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 13:217-231. Available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/44092791/whatsapp_goes_ to_school.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ 2Y53UL3A&Expires=1554373417&Signature=h9kyl2FemBxmIeAk6KK oIm9e668%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DWhatsApp_Goes_to_School _Mobile_Instant_M.pdf. Accessed 4 April 2019. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

Buczynski S & Hansen CB 2010. Impact of professional development on teacher practice: Uncovering connections. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3):599-607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.006 [ Links ]

Christie P 2008. Opening the doors of learning: Changing schools in South Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: Heinemann. Available at http://www.radio.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/ 104/openingthedoors.pdf. Accessed 26 March 2019. [ Links ]

Coto M & Dirckinck-Holmfeld L 2008. Facilitating communities of practice in teacher professional development. In V Hodgson, C Jones, T Kargidis, D McConnell, S Retalis, D Stamatis & M Zenios (eds). Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Networked Learning. Lancashire, England: University of Lancaster/Thessaloniki, Greece: South East European Research Centre (SEERC). Available at http://www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/past/nlc2008/abstracts/PDFs/Coto_54-60.pdf. Accessed 26 March 2019. [ Links ]

Gon S & Rawekar A 2017. Effectivity of e-learning through WhatsApp as a teaching learning tool. MVP Journal of Medical Sciences, 4(1):19-25. https://doi.org/10.18311/mvpjms/2017/v4i1/8454 [ Links ]

Gülbahar Y 2014. Current state of usage of social media for education: Case of Turkey. Journal of Social Media Studies, 1(1):53-69. https://doi.org/10.15340/2147336611763 [ Links ]

Gunawardena CN, Hermans MB, Sanchez D, Richmond C, Bohley M & Tuttle R 2009. A theoretical framework for building online communities of practice with social networking tools. Educational Media International, 46(1):3-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523980802588626 [ Links ]

Jita LC & Mokhele ML 2014. When teacher clusters work: Selected experiences of South African teachers with the cluster approach to professional development. South African Journal of Education, 34(2):Art. # 790, 15 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071132 [ Links ]

Kharade S 2016. What is the difference between Facebook and WhatsApp? Available at https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-difference-between-Facebook-and-WhatsApp-2. Accessed 12 March 2016. [ Links ]

Lautenbach G 2011. Learning to be researchers in an e-maturity survey of Gauteng schools. South African Journal of Education, 31(1):44-54. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n1a357 [ Links ]

Little JW 2003. Inside teacher community: Representations of classroom practice. Teachers College Record, 105(6):913-945. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Judith_Warren_Little/publication/280017903 _Inside_Teacher_Community_Representations_ of_Classroom_Practice/links/575acd4c08aed884620d917d/Inside-Teacher-Community-Representations-of-Classroom-Practice.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2019. [ Links ]

Luft JA & Hewson PW 2014. Research on teacher professional development programs in science. In NG Lederman & SK Abell (eds). Handbook of research on science education (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Malecela IO 2016. Usage of Whatsapp among postgraduate students of Kulliyyah of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science (IJAERS), 3(10):126-137. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers/310.21 [ Links ]

Mamba MSN & Isabirye N 2015. A framework to guide development through ICTs in rural areas in South Africa. Information Technology for Development, 21(1):135-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2013.874321 [ Links ]

McLoughlin C & Lee MJW 2008. Mapping the digital terrain: New media and social software as catalysts for pedagogical change. In Hello! Where are you in the landscape of educational technology? Proceedings ascilite Melbourne 2008. Available at http://www.ascilite.org/conferences/melbourne08/procs/mcloughlin.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2016. [ Links ]

Mestry R, Hendricks I & Bisschoff T 2009. Perceptions of teachers on the benefits of teacher development programmes in one province of South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 29(4):475-490. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/292/171. Accessed 16 March 2019. [ Links ]

Moloi KC, Gravett SJ & Petersen NF 2009. Globalization and its impact on education with specific reference to education in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 37(2):278-297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143208100302 [ Links ]

Mushayikwa E 2013. Teachers' self-directed professional development: Science and Mathematics teachers' adoption of ICT as a professional development strategy. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 17(3):275-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/10288457.2013.848540 [ Links ]

Ndlovu M & Hanekom P 2014. Overcoming the limited interactivity in telematic sessions for in-service secondary mathematics and science teachers. In L Gómez Chova, A López Martínez & I Candel Torres (eds). Proceedings of EDULEARN14 Conference 7th-9th July 2014, Barcelona, Spain. Valencia, Spain: IATED Academy. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264117222_OVERCOMING_THE_LIMITED_ INTERACTIVITY_IN_TELEMATIC_SESSIONS_FOR_IN-SERVICE_SECONDARY_MATHEMATICS_AND_SCIENCE_TEACHERS. Accessed 26 March 2019. [ Links ]

Niess ML 2011. Investigating TPACK: Knowledge growth in teaching with technology. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 44(3):299-317. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.44.3.c [ Links ]

Owen M, Grant L, Sayers S & Facer K 2006. Social software and learning. [ Links ]

Roman R & Wertlen R 2008. An overview of ICT innovation for developmental projects in marginalised rural areas. Paper presented at the Prato CIRN 2008 Community Informatics Conference: ICTs for Social Inclusion: What is the Reality, Prato, Italy, 27-30 October. Available at http://www.developmentinformatics.org/conferences/2008/papers/wertlen.pdf. Accessed 26 March 2019. [ Links ]

Sayan H 2016. Affecting higher students learning activity by using WhatsApp. European Journal of Research and Reflection in Educational Sciences, 4(3):88-93. Available at http://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/AFFECTING-HIGHER-STUDENTS-LEARNING-ACTIVITY-BY-USING-WHATSAPP-Full-Paper.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2019. [ Links ]

Schlager MS & Fusco J 2003. Teacher professional development, technology, and communities of practice: Are we putting the cart before the horse? The Information Society, 19(3):203-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240309464 [ Links ]

Shohel MMC & Banks F 2012. School-based teachers' professional development through technology-enhanced learning in Bangladesh. Teacher Development, 16(1):25-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.668103 [ Links ]

Smylie MA 2014. Teacher evaluation and the problem of professional development. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 26(2):97-111. Available at https://www.mwera.org/MWER/volumes/v26/issue2/v26n2-Smylie-POLICY-BRIEFS.pdf. Accessed 13 March 2019. [ Links ]

Sparks D 2017. Top 10 social networks: How many users are on each ? Available at https://www.fool.com/investing/2017/03/30/top-10-social-networks-how-many-users-are-on-each.aspx. Accessed 18 February 2017. [ Links ]

Steyn GM 2011. Continuing professional development in South African schools: Staff perceptions and the role of principals. Journal of Social Sciences, 28(1):43-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2011.11892927 [ Links ]

Surowiecki J 2004. The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies, and nations. New York, NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Susilo A 2014. Using Facebook and WhatsApp to leverage learner participation and transform pedagogy at the Open University of Indonesia. Jurnal Pendidikan Terbuka dan Jarak Jauh, 15(2):63-80. Available at http://ilp.ut.ac.id/index.php/JPTJJ/article/view/208/165. Accessed 4 April 2019. [ Links ]

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H & Bondas T 2013. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3):398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048 [ Links ]

Van Weert TJ 2006. Education of the twenty-first century: New professionalism in lifelong learning, knowledge development and knowledge sharing. Education and Information Technologies, 11(3-4):217-237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-006-9018-0 [ Links ]

Vanwynsberghe H & Verdegem P 2013. Integrating social media in education. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 15(3):1-10. https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2247 [ Links ]

Wenger E 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wenger E 2011. Communities of practice: A brief introduction. Available at https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/11736. Accessed 27 March 2019. [ Links ]

Wetzel KA, Zambo R & Buss RR 2000. Professional development for transformative teaching with technology in K-8 classrooms. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 16(2):15-20. [ Links ]

Yang SH 2009. Using blogs to enhance critical reflection and community of practice. Educational Technology & Society, 12(2):11-21. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jeductechsoci.12.2.11.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2019. [ Links ]

Yeboah J & Ewur GD 2014. The impact of Whatsapp Messenger usage on students performance in tertiary institutions in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(6):157-164. [ Links ]

Received: 23 May 2016

Revised: 28 November 2018

Accepted: 29 March 2019

Published: 31 May 2019