Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 n.2 Pretoria May. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1512

ARTICLES

The value of teaching practice as perceived by Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) students

Siphokazi Kwatubana; Mark Bosch

Faculty of Education, Edu-Lead, North West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa. sipho.kwatubana@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The pursuit of excellence in preparing student teachers for the teaching profession is a never-ending endeavour. This study aimed at investigating the value of teaching practice as perceived by the participants, how they determined such value using human judgement and whether value judgement can be used as a form of reflection during teaching practice by PGCE students. Human judgement can be used as a tool to promote reflection and an evaluation strategy which promotes a culture of observation and critical thinking about one's practice. The qualitative study involved 25 participants, all of whom were Postgraduate Certificate in Education students and had completed the practical teaching period. In this study we applied Kant's theory to analyse the data gathered by means of narratives. The results, which were based on self-reported values on teaching practice, revealed that the participants viewed teaching practice as valuable and pointed out that it benefitted them and others by enabling them to gain valuable experience in the classroom and in general school management. The participants based their judgement on three components of value judgement, both negative and positive: emotions, attitudes and experiences.

Keywords: Postgraduate Certificate in Education; student teachers; teaching practice; value judgement on teaching practice; value of teaching practice

Introduction

The importance of teaching practice in initiating pre-service and novice teachers into real life in schools has become firmly established in the research literature (Quick & Siebörger, 2005), whereupon all the concepts that the students have learned need to be applied in real-life situations (Bhargava, 2009). This research in South Africa has been conducted in contexts in which policy standards and training and development documents such as the South African National Education Policy Act 53 of 2000 and the Minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications (MRTEQ) (Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa, 2015), have increasingly prioritised teaching practice. These policies become means of providing an authentic context within which the student teacher is exposed to and experiences the complexities and richness of the reality of being a teacher. Since student teachers typically describe their teaching practice as the most important and relevant aspect of their training (Standal, Moen & Moe, 2014), there is a need for exploration of multiple opportunities and formats for reflection (Bean & Stevens, 2002). The use of judgement and evaluation becomes relevant in determining the value of teaching practice. Making judgements about the value of teaching practice can foster reflection that may empower student teachers, especially PGCE students, to "critically evaluate good practice" (Loughran, 2002:40). The PGCE, a teaching training programme offered at university level in South Africa, offers a one-year full-time professional teaching qualification to students holding bachelor's degrees.

In South Africa, a developing country, the abundance of resources significantly contributes to economic activity. However, the mineral resources cannot be fully utilised due to a lack of skilled human resources (Musingwini, Cruise & Phillips, 2013). Statistics South Africa indicated that unemployment in South Africa was at a record high in 2016. Bhorat and Jacobs (2010) attribute the high rate of unemployment to a structural change observed in labour demand trends shifting towards high-skilled workers. More and more people in the labour force hold tertiary qualifications, however, the level of unemployment among this group is increasing (Daniels, 2007) as more and more graduates search for jobs each year. In an effort to become employable, many unemployed graduates pursue further studies in different fields, which includes teacher education.

Although several studies have been conducted on student teachers' experiences and anxieties during teaching practice (Maphosa, Shumba & Shumba, 2007), a review of the literature indicates that limited studies have been conducted on perceptions of the value of teaching practice. This study seeks to contribute towards the discourse on teaching practice in general, and formats for reflection, in particular. In this article we argue that student teachers can express their attitudes towards the teaching profession if, and only if, they judge the value thereof.

Background

Teaching practice is guided by policies, among others, the South African National Education Policy Act 53 of 2000 and the Minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications (MRTEQ) (Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa, 2015), which prescribe that practical learning and work integrated learning should be spread across the academic programme. The school experience component should take place in blocks of varying duration throughout the programme. Where a more extended period is envisaged, such as during part of a final year or within a structured mentorship programme, proper supervision, suitable school placement and formal assessment should be guaranteed (Department of Education [DoE], Republic of South Africa, 2007).

Depending on the institution, teaching practice may be conducted in a number of ways (Perry, 2004). At the university where this study was conducted, all PGCE students do observation for two weeks before the March recess, then do teaching practice for four weeks during May and another four weeks during July and August - a total of two and a half months. At other universities 12 weeks per year are allocated for teaching practice.

When students register for the PGCE the assumption is that they have acquired the subject knowledge during their undergraduate studies and that the PCGE programme is to equip them with the knowledge and competence needed for teaching. During teaching practice university lecturers visit schools to assess the students, but the students are mostly guided and supervised by the teachers at the respective schools.

According to Steyn and Killen (2001) teaching practice can sometimes become a discouraging and terrifying experience. Challenges of "geographical distance, low and uneven levels of teacher expertise, a wide-ranging lack of resources as well as a lack of learner discipline can be demoralising" (Marais & Meier, 2004:221). These negative encounters, as well as fear of the unknown and the wrong career choice (Quick & Siebörger, 2005) may affect student teachers' perceptions of the usefulness of teaching practice, which in turn can influence their views of the teaching profession.

On the flip side, good experiences encountered during teaching practice may lead to positive judgements. In their study, Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne (2011) found that student teachers felt that their self-confidence was strengthened during teaching practice. McNay (2004) posits that teaching practice is often described by student teachers as the most worthwhile experience of their study programme as that is where they really learn to teach. Lampert (2010) reports that teaching practice helps student teachers gain skills and knowledge about schools, learners, teaching, school routine, teaching practice, teaching theory, staff meetings and, most importantly, the nature of the child. Furthermore, Busher, Gündüz, Cakmak and Lawson (2015) state that the opportunity to work with experienced teachers hones student teachers' skills. Therefore, good experiences during teaching practice appear to lead to positive judgements.

The aim of this paper was to investigate how PGCE students at a university in South Africa perceived the value of teaching practice, how these participants determined this value, and whether value judgement can be used as a form of reflection during teaching practice by PGCE students. The following research questions were used: What is the value of teaching practice? How do students determine the value of teaching practice? Can value judgements be used as a form of reflection?

Literature Review

Our search for research literature on value judgement in teaching practice yielded no results. It is for that reason that Wilson (1992) suggests that there is a need for such education research to be conducted. Value is "the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, usefulness of something or the positive quality of being precious" (Oxford University Press, 2019: para. 1). It is the quality that renders something desirable or valuable or useful, something that one hopes to attain. People assign a value to an object - in this research the object is teaching practice, which is presumably undertaken by students to achieve their dreams of becoming professional educators. In assigning value to this object, judgements are then made about its worth by means of, among other factors, appraisals, assessments and calculations. Although value judgement does not only apply to education, it is particularly important in making decisions on how well the educational goal is realised. A better understanding of how student teachers judge teaching practice may thus provide clues about measures that may be taken to better prepare student teachers for teaching. For instance, a negative judgement will be based on negative experiences, which may negatively affect the student teacher's attitude. Attitude is essential in that it shows mental preparedness for action during their teaching career.

Risley (2005) states that throughout human history, personal experience has served as a guide to conduct. Virtually everyone relies on their own experiences to make evaluations about their own actions. Dewey (1934, cited in Schmidt, 2010) argues that educators must first understand the nature of human experience, as, according to his theory (Dewey, 1934), experience arises from the interaction of two principles, namely continuity and interaction. Continuity means that each experience a person has will influence the person's future, for better or for worse. Interaction refers to the situational influence on one's experience (Dewey, 1963). In other words, one's present experience is a function of the interaction between one's past experiences and the present situation.

It is equally important to understand that no experience has a pre-ordained value (Dewey, 1963). What may be a rewarding experience for one person may be unrewarding for another. The value of the experience must thus be judged by the effect that it has on the individual's present and future, and the extent to which the individual is able to contribute to society (Alfred, Byram & Fleming, 2003). Kiggundu (2007) opines that a lack of resources, a lack of discipline among a wide cross-section of learners, and educators' attitudes are some of the negative challenges that may negatively impact student teachers' experiences.

In teacher education, students are taught, among other aspects, different theories pertaining to learner discipline, administration and management, professional ethics and teaching methodologies. The practical teaching period gives students an opportunity to test these theories. Their effectiveness depends on people's ability to evaluate the information and then to integrate it into their day-to-day activities in the school environment. Consequently, how theory and practice are dealt with is likely to influence the way in which an individual student teacher evaluates his or her experiences. It can happen that student teachers do not consider all possibly relevant information before making a judgement, but instead compress most of the relevant information accessible to them (Clore & Huntsinger, 2007).

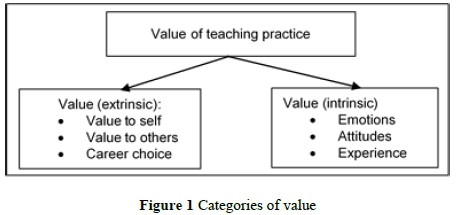

The value of teaching practice lies in extrinsic and intrinsic value. Zimmerman (2008) claims that the intrinsic value of something is the value of the thing in itself, or for its own sake, or as such, or in its own right, whereas the extrinsic value of something is less directly expressive of such inherent (but fragile) tendencies. Figure 1 outlines the categories of value discussed in this section.

This information is irrelevant without the knowledge of processes and procedures in schools, relationships between teachers, learners and school managers. Knowledge regarding the learner to be taught is paramount. By knowing the learners, student teachers can make judgements about the nature of the learners, their behaviour and their learning, which can enable student teachers to choose the most appropriate teaching strategies.

Emotions play a major role in evaluations. In addition, emotions or affects provide compelling information about the personal value of whatever is in mind at the time (Clore & Huntsinger, 2007). Loewenstein and Lerner (2003) and Peters (2006) describe emotions as external forces influencing a non-emotional process. Thus, although emotions may have an influence on judgement, the latter might proceed without emotion.

Positive emotions can influence cognition and motivation (Sutton & Wheatly, 2003). People's judgements often reflect their current moods. When in a happy mood, people judge many things, from consumer goods to life-satisfaction more positively than when they feel unhappy (Yeung & Wyer, 2004). Furthermore, Wyer, Clore and Isbell (1999, cited by Clore & Huntsinger, 2007) state that moods generate like or dislike by activating positive or negative beliefs about the object of judgement. A plethora of researchers (Pham, 2004, 2008; Schwarz & Clore, 2007) have concluded that judgments can be influenced by affective feelings. As feelings are experienced, student teachers may continuously ask themselves how they feel about the teaching practice period (the scheduled time for teaching practice might be preceding a hectic period for the student that may leave no room for emotional preparation), school environment (if the physical environment is not well maintained, it can lead to a depressive mood), conditions at the school, and support provided to them by their mentors. According to Pham (2008) student teachers can use this experiential information to form a variety of judgments.

According to Pfister and Böhm (2008) there is ample evidence that emotions, whether immediate or anticipated, frequently influence judgments. Anticipated emotions are beliefs about one's future emotional states that might ensue when the outcomes are obtained. Two variants of immediate emotions exist - those that are incidental, caused by factors that are not related to the object of judgement at hand, and those that are anticipatory or integral, which are triggered by the object of judgement itself (Loewenstein & Lerner, 2003). Gutnik, Hakimzada, Yoskowitz and Patel (2006) argue that attitudes are influenced by emotions, which in turn influence judgements.

Theoretical Framework

Kant's (1892) theory of judgement underpins this research. There is a growing interest in the use of Kant's theory in education, and Derrida's (2004) and Readings' (1996) pursuit of knowledge using this theory bears evidence. Moreover, Rolfe (2013) investigated difficulties and tensions encountered at the interface between a professional practice and an academic discipline, while Moran (2015) investigated conception of pedagogy using Kant's theory as lens. In essence these issues are relevant to a South African education system that is struggling to increase the matching of educational supply with labour market.

Kant's (1892) theory indicates that human beings have the inherent ability to make judgements to orient themselves in the world and to determine the value of their experiences. Judgement is therefore conditional upon human beings' ability to enter the space of reason, and thereby to gain practical understanding of the world. Judgement allows human beings to understand and position themselves in, and relate themselves to the world, as well as to relate with other people (Düring & Düwell, 2015). A variety of contemporary Kantian philosophers (notably, Herman, 2007; Makkreel, 2015; Waxman, 2014) emphasise that the Kantian perspective does not start philosophical inquiry with concepts and propositions, but with judgement. According to Düring and Düwell (2015:943) different types of judgement exist, which include theoretical, prudential, moral, aesthetic and mixed judgements. In more complex circumstances singular judgements are not adequate and so a combination of different types of judgement of a mixed nature is employed. People judge the existence and qualities of objects and often disagree about their judgements, yet at the same time also understand each other to some degree.

Our research focuses on PGCE students' judgement of their experience of teaching practice. According to Kant (1998), priori knowledge precedes experience. The theory indicates that experience itself is a kind of cognition, an active exercise of the mind which requires understanding of empirical judgements. Experience must involve the senses and thought or understanding. This understanding is termed as the capacity to make judgements. In making a judgement one is active as opposed to being passive by taking a stand on how things are or how things ought to be.

An empirical investigation was conducted to apply the Kantian theory to PGCE students' value judgements about their experiences of teaching practice.

Research Methodology

A qualitative study using narratives as a data collection tool was employed in this study, which was conducted once ethical clearance had been granted by the University. We utilised the informants' first-person narratives about their own experiences of teaching practice. The three aspects of the narrative approach indicated by Clandinin and Connelly (2000), namely personal and social (interaction), past, present, and future (continuity), and place (situation) were regarded suitable for this research. Data was collected in two phases. The first phase was done at the end of the ten-week teaching practice period in August, immediately after the recess. The timing of the first phase was based on Schwarz and Bohner's (2001:439) model of "memory causes judgement and judgement causes memory." The intention was to solicit raw data while the information was still fresh in the participants' minds. Phase two of the data collection was carried out in October, and this enabled the researchers to deal with the bias of selective recollection of information.

The participants in this study were drawn from one of the campuses of the University. All the PGCE student teachers of the 2015 cohort were willing to participate (n = 78). The invitation letter informing the potential participants of the particulars of the study, its duration, activities, location, and the amount of time that would be required was distributed to the PGCE students by a lecturer who was not part of the research team. The potential participants had to express their willingness to participate in the study by making themselves available at the location indicated in the letter, to which all 78 students responded.

Structured open-ended questionnaires were administered to the participants. As indicated by Nieuwenhuis (2007), the questions were developed in advance. Four open-ended questions were asked:

1. What do you think the value of teaching practice is?

2. How did the experience you gained during teaching practice help you to determine its value? Elaborate.

3. How did the information and knowledge you already had about teaching influence your judgement? Elaborate.

4. Did your emotions and attitude during teaching practice affect your judgement? Elaborate.

Structured open-ended interviews are used in larger sample groups to ensure consistency (Neuman, 2003). The choice of this data collection method was based on the assertion by Neuman (2003) that open-ended questions yield adequate answers to complex issues. The participants were allowed a week to peruse the first set of three questions in the first phase on their own in their own time. The class representative was responsible for the distribution and collection of the responses. The participants were assured of the strict confidentiality of information (no names or student numbers were indicated on the questionnaires). The participants who were selected as informants were chosen on the basis of defined qualities. They were PGCE students who had completed the ten-week teaching practice according the University's requirements. These participants were selected for the express purpose of obtaining the richest possible information to answer the research question.

In the second phase the students were given the same set of questions as in the first phase, namely: What do you think is the most important value of teaching practice? Give reasons. Which of the following components influenced you most in making your judgement: experience during teaching practice, information and knowledge you already have about teaching, your emotions and attitude during practice teaching? Elaborate.

Among the participants were students who had completed their qualifications in various disciplines as indicated in Table 1. Not all data was transcribed because the saturation point was reached after capturing data from 25 participants (n = 25). The researchers agreed to stop transcribing when they realised that no new information was forthcoming from the responses. To ensure trustworthiness, we archived the data that was not transcribed. After the analysis of the transcribed data we decided to transcribe the archived data and analyse that as well. We then compared the two sets of findings to test validity. The results were the same as in the preliminary analysis. The use of a wide range of informants allowed for verification of different points of view and experiences. As indicated by Fossey, Harvey, McDermott and Davidson (2002), the aim in qualitative enquiry is not to acquire a fixed number of participants, but rather to gather information of sufficient depth as a way of fully describing the phenomenon being studied. Inductive analysis was done and themes were formed.

Results

Extrinsic Value

Value to self

Teaching practice reportedly benefited student teachers in that it gave them confidence and boosted their self-esteem. Their confidence was boosted through their experience in the exposure to schools during the two placements. To emerge as a fully capacitated teacher, the student must develop confidence during the time when he or she is being prepared for teaching through practical training. Participants indicated that teaching practice reduced the fear of standing in front of a class. Indeed, assuming the responsibility of directing learning to a group of students while being observed by more experienced teachers over a period of time can eliminate fear. The participants made a number of interesting statements regarding the skills they had acquired during teaching practice.

It created within me a caring heart, self-confidence (P4); It helps in building confidence (P1); I am now able to stand in front of a class without nerves getting the hold of me (P5); I no longer have fear of standing in front of learners (P6); my confidence and self-esteem increased with every successful lesson (P7); It helped me become more confident when teaching (P12); really helped me to build my self-confidence in front of the learners. I am a bit more equipped (P13); it improved my talking skills (P19); I can teach and manage the class effectively (P3).

Career choice

The participants indicated that their exposure to schools helped them to make the final decision regarding their career choice. It appeared that they were not too sure about their career choice up to that point and that they were waiting for that moment to decide. This could be true as students are exposed to the realities of experiencing the complexities and the richness of being a teacher. If they were unsure when they registered for the teachers' programme, this experience would become a deciding factor. As they could have been at a cross-roads exposure to real school scenarios would help them to either commit to teaching, which could result in a positive attitude towards teaching, or reject teaching altogether - especially if teaching was chosen by default. Students who are still unsure about taking up teaching after two or three placements, may choose not to teach after completing the programme. From their statements it can be deduced that that was a make-or-break moment for the student teachers.

It tends to resolve any reservations that the students might be experiencing, creates self-awareness in terms of whether this is the profession you want or not (P2); it guides us in making informed and responsible decisions about our future (P10); helps you to decide whether this is the right career choice for you (15); once a student teacher has successfully completed his/her practice and still wants to be an educator, he or she is in the right job (P3); it helps us see if we are cut out to be teachers (P8); helps us to decide if it is the correct career path for us (P12); you can decide whether you want to be in this profession or not (P19); helps you to determine whether or not you have chosen the correct profession (P24).

The majority of respondents indicated that they found value in teaching practice as they were given an opportunity to test the theoretical aspects they had learnt before getting into the real world of the teaching profession. It seems that these students were able to derive maximum benefit from the exercise. This was an opportunity for them to gain first-hand experience on how to apply theories learnt and to determine whether they worked or not.

Teaching practice is a platform where student teachers get the hang of things (P5); it gives students the opportunity to live the real experiences of all the theory they have been learning (P9); because you can actually go and apply what you learned in class so that you have a good idea of what to do as a full-time teacher (P25); it gives me the opportunity to try the art of teaching before actually getting into the real world of the teaching profession (P18); there is a difference between theory and practice, I realised that when I was in schools (P11); I struggled to maintain discipline, the information I had was not enough (P20).

Value to others

It should be noted that student teachers found that teaching practice was valuable to the learners as well. It seems that the student teachers were happy to be of assistance to others motivated by altruistic reasons. This could then evoke a deep desire to help society improve, thus, making teaching socially worthwhile for all. Teaching practice seemed to have been a wonderful opportunity for them to impart their knowledge to learners.

Helping and giving back your knowledge to the learners, making a difference in a child's life (P4); to be hands-on in the development of others (P5); although I couldn't teach I was able to clarify concepts that they were struggling to understand in accounting, it felt good (P15).

Intrinsic Value

Emotions

The participants based their judgement on both positive and negative affective reactions. The negative emotions were based on fear, feelings of inability, learners' bad attitudes and loss. Teaching itself is an emotional endeavour. Because of the intensity of interaction in the classroom, emotions evoked are natural. These challenges can be regarded as part of teaching or of being a teacher. Positive judgements were made based on satisfaction, feelings of fulfilment, lack of fear, love, excitement and success.

Teachers and learners made me feel like I was a qualified teacher already (P1); with your PGCE it is fantastic (P25); it created within me a caring heart (P4); I felt out of my depth (P11); the fulfilment I get after teaching learners (P3); it was good exposure to the field (P10); I am excited and can't wait to be appointed (P5); I no longer have fear of standing in front of learners (P6); what I remember is that I couldn't control the shaking in my knees each time I stood in front of a class (P20); learners can be cruel and nasty, that makes you question if what you are doing is right or wrong (P8); after a bad lesson you are devastated (P24) [sic].

Attitudes

Positive and negative attitudes influenced participants' judgements. Their attitudes and those of others informed their assessment. The participants appreciated the positive attitudes displayed by the teachers at schools, while the negative actions of the learners made them feel alienated. For some of the participants negative perceptions changed to positive, while others' points of view remained unchanged.

I love working with learners (P25); I have new appreciation for the profession that I once took for granted (P9); draw positives from the negatives and make a change or difference in the lives of the learners (P5); the learner is always right and it is expected that you must protect yourself from learners (P21); learners are difficult to understand and control (P16); learners of today are disrespectful (P14) [sic].

Experience

The participants had negative experiences with learners and teachers whom they felt were not helpful. These bad experiences were linked to their own lack of preparation for classes and the lack of clarity on theory. There were, however, those who had good experiences with respectful learners. They came to realise that teaching was hard work.

Learners can be very naughty and if the teacher is not prepared they make fun of you (P14); teachers at school don't really mentor us, we are on our own (P22); they don't show us where we are going wrong (P17); if the teacher is not prepared the learners make fun of you. Learners don't learn and can't cope with the workload (P8); you do have guidelines but not always clear guidelines for dealing with difficult learners at a specific time (P23); I received a lot of respect and learners looked up to me to be the best mentor I never had (P7); experienced mutual respect in the classroom and in the school yard in general (P19); I realised it wasn't as easy as I thought it would be, and that it is hard work being a teacher (P24); it is more valuable than most qualifications where you just do theory and never apply what you learned (P25) [sic].

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand the perceptions of student teachers regarding the value of teaching practice and, using Kantian theory, understand how this value was determined. Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2003) and Perry (2004:4) perceive teaching practice as the crux of student preparation for the teaching profession since it provides the "real interface" between studentship and membership of the profession.

The first finding from the analysis of student teachers' responses suggests the usefulness of self-benefits of teaching practice. The participants indicated that they benefitted from teaching practice in that they acquired skills, that teaching practice was a testing ground for learnt theory, and in many cases, teaching practice presented an opportunity for students to decide whether they would embrace teaching as profession or not. Although gaining confidence and skills is a value in itself, these benefit learners indirectly. Kant (1892) indicates that to make judgements about skills one needs to apply the rules. Rules in this sense pertain to the teaching theories that students learn at university. Theories of teaching do not have strict rules as those that are applicable in mathematics and science, therefore, they leave room for interpretation of application. This kind of judgement is determinative judgement. Acquiring skills in teaching, class management, handling learner behaviour and professional relationships with other staff members helped student teachers to create positive opinions about themselves. This process gives the student teacher an opportunity to improve his or her classroom management skills. The self-gain was not limited to academic development but extended to awareness of the participants' affective attributes: their love for children and teaching.

The results of this study suggest that although the students were approaching the end of their study programme, they still needed an opportunity to make a final decision about the career they had chosen. One would think that this would have been long resolved by the time they enrolled for the programme at the beginning of the year. Even after the teaching practice period, some students were still unsure about their choice. It emerged that the teaching practice period was particularly important for the PGCE students. Moreover, it seems that the participants were at a career cross-roads, as they were just about to complete the programme and seek employment. Furthermore, they needed to check whether the teaching skills that they had acquired would be enough to secure teaching positions. The question of whether they would be employable or not, after having completed the PGCE programme, now became crucial. According to Kant (1998:23) judgement is based on perceptions and experience. Judgement of experience is based on the object of experience, which, in relation to this finding, is the ability or inability to secure work. The analogies of experience indicated by Kant (1998) include relations between objects of experience, cause and effect and coexistence of objects of experience leading to causal interaction. In this case a relationship exists between acquiring a skill and securing employment. The cause in this instance is gaining a skill and the effect is being employable or not. These two objects coexist during the time when PGCE students are preparing themselves for the job market. Being anxious about the prospects of employment is understandable as these students had completed their first degrees and some attempted to find jobs before enrolling for the PGCE. It seems as though it was important for student teachers to experience teaching first-hand in order for them to make the final decision to become teachers. Teaching practice thus served as a basis for forming a judgement about how the teaching skills they had acquired were leading to another object of experience - the right career choice. Although research has shown that teaching practice is an opportunity for aspiring teachers to establish whether they have made the right career choice (Bhargava, 2009), for PGCE students this becomes a vicious cycle: being caught up between objects of experience.

The participants were unanimous about the value of practising in enabling them to test the theory learned at university. Although some were positive about the benefits, others indicated that they had gained awareness of the difference between theory and practice and that not all theories were applicable to all situations. This was a valuable discovery for students who were about to become full-time teachers. This insight could help students to develop their own models of class management using some ideas from the existing theories.

The second finding is that judgement made on teaching practice was based on three components, namely emotions, attitudes and experiences. Emotions were pervasive influences on the students' judgements and thoughts. Positive emotions that informed the judgements made about teaching practice included feelings of fulfilment, of being in control, of success, of love and excitement. These positive emotions influence motivation (Sutton & Wheatly, 2003). The expression of emotions by student teachers encode reality, which is typical for the experiential processing of human beings (Evelein, Korthagen & Brekelmans, 2008). Negative emotions comprised fear, feelings of inability, learners' bad attitudes and loss. Researchers confirm that teaching practice can be a discouraging, terrifying experience (Steyn & Killen, 2001), exacerbated by fear of the unknown (Quick & Siebӧrger, 2005). These emotions can affect the students' view of the teaching profession. Participants who experienced negative emotions gave valuable information regarding the inadequacy of information they had, which made it difficult for them to deal with problems they encountered during teaching practice. When referring to feelings, Kant (2001) talks about the judgement of the agreeable, which pertains to private feelings that are only valid for the person who likes the object as in the positive emotions discussed above. On the other hand, judgement of taste has a universal validity because everybody likes/dislikes the object. In this finding both types of judgements came to the fore: the judgement of the agreeable, which is more sensational in nature, and the judgement of taste, which is regarded as a taste of reflection. One is tempted to argue that for PGCE students to make judgements they must know what the object (classroom, learner behaviour, relationships within the school) is meant to be, thus, having a determinate concept of the object. On the contrary, Kant (2001) does not believe that a judgement of taste is based on concepts as it is not a cognitive judgement.

Judgement in this research was memory-based and the participants were able to remember vividly their attitudes and experiences. Good experiences can lead to a boost in self-confidence (Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2011). The positive experiences were based on the relationships with learners and teachers, whereas the negative experiences were based on the absence of preparation for classes and ambiguities in theories. Students who had negative experiences indicated the importance of gaining skills and enhancing self-esteem. The findings in this research also indicate clearly that value judgement was a possible method of reflection on teaching practice by PGCE students.

Conclusion

This was an explorative study based on a theory of value judgement in soliciting data on the perceptions of PGCE students on the value of teaching practice. The findings give a clear answer to the two research questions discussed in the foregoing sections. This research found that when assigning value, people use different components of judgement. All the components, namely attitudes, emotions and experiences, were indicated as important in determining the value of teaching practice. Students also used different types of judgements.

According to Kant, freedom is the defining aspect of human nature. This study's findings are in line with Kant's (2007:440) postulation that "with the current education the human being does not fully reach the purpose of his existence." The fact that PGCE students were still in doubt regarding to whether the newly acquired skills would enable them to enter the labour market successfully, supports Kant's postulation.

Therefore, we recommend that in addition to the reflective journals that are submitted at the end of teaching practice for which students are awarded marks, reflection based on value judgement should also be included. The reflective journal only is inadequate for a PGCE student who is still grappling and directly affected by the rising unemployment levels. The reflective journal is utilised as a way of demonstrating the acquisition of certain skills and attributes and as evidence of learning during teaching practice. We concur with Düring and Düwell (2015) who postulate that the capacity to form judgments is the basic power that human beings need to orient themselves in the world. Students can be taught about the theories that pertain to value judgement and apply them during teaching practice. The findings of this research have pedagogical implications for the teaching practice component of the PGCE programme.

Authors' Contributions

Siphokazi Kwatubana wrote the manuscript, Mark Bosch provided data for Table 1, Mark Bosch conducted the surveys, and both authors did the statistical analyses. Both authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Alfred G, Byram M & Fleming M 2003. Introduction. In G Alfred, M Byram & M Fleming (eds). Intercultural experience and education. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

Bean TW & Stevens LP 2002. Scaffolding reflection for preservice and inservice teachers. Reflective Practice, 3(2):205-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940220142343 [ Links ]

Bhargava A 2009. Teaching practice for student teachers of B.Ed programme: Issues, predicaments and suggestions. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education (TOJDE), 10(2):101-108. Available at http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/yonetim/icerik/makaleler/484-published.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2019. [ Links ]

Bhorat H & Jacobs E 2010. An overview of the demand for skills for an inclusive growth path. Johannesburg, South Africa: Development Bank of Southern Africa. Available at https://www.dbsa.org/EN/About-Us/Publications/Documents/An%20overview%20of%20the%20demand%20for%20skills%20for%20an%20in clusive%20growth%20path%20by%20Haroon%20Bhorat%20and%20Eln%C3%A9%20Jacobs.pdf. Accessed 1 August 2017. [ Links ]

Busher H, Gündüz M, Cakmak M & Lawson T 2015. Student teachers' views of practicums (teacher training placements) in Turkish and English contexts: A comparative study. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(3):445-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2014.930659 [ Links ]

Clandinin DJ & Connelly FM 2000. Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Clore GL & Huntsinger JR 2007. How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9):393-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.005 [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2003. A guide to teaching practice (4th ed). London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Daniels RC 2007. Skills shortages in South Africa: A literature review (DPRU Working Paper 07/121). Cape Town, South Africa: Development Policy Research Unity. Available at http://www.dpru.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/36/DPRU%20WP07-121.pdf. Accessed 2 August 2017. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Republic of South Africa 2007. National Education Policy Act (27/1996): The National Policy Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa. Government Gazette, 502(29832):1-40, April 26. Available at https://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/NPF_Teacher_Ed_Dev_Apr2007.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2019. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa 2015. National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Revised policy on the minimum requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Government Gazette, 596(38487):1-72, February15. Available at http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/National%20Qualifications%20Framework%20Act%2067_2008%20Revised%20Policy%20for%20Teacher%20Education%20Quilifications.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2019. [ Links ]

Derrida J 2004. Eyes of the university: Right to Philosophy 2. Translated by J Plug & Others. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Dewey J 1934. Art as experience. New York, NY: Capricorn Books. [ Links ]

Dewey J 1963. Experience and education. New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Düring D & Düwell M 2015. Towards a Kantian theory of judgement: The power of judgement in its practical and aesthetic employment. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 18(5):943-956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-015-9641-1 [ Links ]

Evelein F, Korthagen F & Brekelmans M 2008. Fulfilment of the basic psychological needs of student teachers during their first teaching experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5):1137-1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.001 [ Links ]

Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott C & Davidson L 2002. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6):717-732. [ Links ]

Herman B 2007. Moral literacy. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Gutnik LA, Hakimzada AF, Yoskowitz NA & Patel VL 2006. The role of emotion in decision-making: A cognitive neuroeconomic approach towards understanding sexual risk behavior. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 39(6):720-736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2006.03.002 [ Links ]

Kant I 1892. The critique of judgement. London, England: MacMillan and Company Limited. [ Links ]

Kant I 1998. Critique of pure reason. Translated and edited by P Guyer & AW Wood. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kant I 2001. Critique of the power of judgment. Translated by P Guyer & E Matthews. In P Guyer (ed) (2nd ed). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kant I 2007. Anthropology, history, and education. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kiggundu E 2007. Teaching practice in greater Vaal Triangle area: The student teachers experience. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 4(6):25-35. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v4i6.1572 [ Links ]

Lampert M 2010. Learning teaching in, from, and for practice: What do we mean? Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2):21-34. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487109347321 [ Links ]

Loewenstein G & Lerner JS 2003. The role of affect in decision making. In RJ Davidson, KR Scherer & HH Goldsmith (eds). Handbook of affective science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Loughran JJ 2002. Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1):33-43. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487102053001004 [ Links ]

Makkreel RA 2015. Orientation and judgment in hermeneutics. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. [ Links ]

Maphosa C, Shumba J & Shumba A 2007. Mentorship for students on teaching practice in Zimbabwe: Are student teachers getting a raw deal? South African Journal of Higher Education, 21(2):296-307. [ Links ]

Marais P & Meier C 2004. Hear our voices: Student teachers' experiences during practical teaching. Africa Education Review, 1(2):220-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146620408566281 [ Links ]

McNay M 2004. Power and authority in teacher education. The Educational Forum, 68(1):72-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720308984605 [ Links ]

Moran S 2015. Kant's conception of pedagogy. South African Journal of Philosophy, 34(1):29-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2015.1010132 [ Links ]

Musingwini C, Cruise JA & Phillips HR 2013. A perspective on the supply and utilization of mining graduates in the South African context. The Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 113(3):235-241. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/jsaimm/v113n3/13.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2019. [ Links ]

Neuman WL 2003. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J 2007. Introducing qualitative research. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Oxford University Press 2019. Value. Available at https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/value. Accessed 17 May 2019. [ Links ]

Perry R 2004. Teaching practice for early childhood: A guide for students (2nd ed). London, England: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

Peters E 2006. The functions of affect in the construction of preferences. In S Lichtenstein & P Slovic (eds). The construction of preference. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Pfister HR & Böhm G 2008. The multiplicity of emotions: A framework of emotional functions in decision making. Judgment and Decision Making, 3(1):5-17. [ Links ]

Pham MT 2004. The logic of feeling. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(4):360-369. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1404_5 [ Links ]

Pham MT 2008. The lexicon and grammar of affect as information in consumer decision making: The GAIM. In M Wänke (ed). Social psychology of consumer behavior. New York, NY: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Postareff L & Lindblom-Ylänne S 2011. Emotions and confidence within teaching in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 36(7):799-813. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.483279 [ Links ]

Quick G & Siebӧrger R 2005. What matters in practice teaching? The perceptions of schools and students. South African Journal of Education, 25(1):1-4. [ Links ]

Readings B 1996. The university in ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Risley T 2005. Montrose M. Wolf (1935-2004). Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38(2):279-287. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2005.165-04 [ Links ]

Rolfe G 2013. Thinking as a subversive activity: Doing philosophy in the corporate university. Nursing Philosophy, 14(1):28-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769X.2012.00551.x [ Links ]

Schmidt M 2010. Learning from teaching experience: Dewey's theory and preservice teachers' learning. Journal of Research in Music Education, 58(2):131-146. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022429410368723 [ Links ]

Schwarz N & Bohner G 2001. The construction of attitudes. In A Tesser & N Schwarz (eds). Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470998519 [ Links ]

Schwarz N & Clore GL 2007. Feelings and phenomenal experiences. In AW Kruglanski & ET Higgins (eds). Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Standal ØF, Moen KM & Moe VF 2014. Theory and practice in the context of practicum: The perspectives of Norwegian physical education student teachers. European Physical Education Review, 20(2):165-178. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356336X13508687 [ Links ]

Steyn PDG & Killen R 2001. Reconstruction of meaning during group work in a teacher education programme. South African Journal of Higher Education, 15(1):61-67. Available at https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/high/15/1/high_v15_n1_a7.pdf?expires=1555256688&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=9AE83CC07E7C9F780F4C459712E2694B. Accessed 14 April 2019. [ Links ]

Sutton RE & Wheatley KF 2003. Teachers' emotions and teaching: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4):327-358. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026131715856 [ Links ]

Waxman W 2014. Kant's anatomy of the intelligent mind. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Wilson J 1992. Value judgements and educational research. British Journal of Educational Studies, 40(4):350-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.1992.9973937 [ Links ]

Yeung CWM & Wyer RS Jr 2004. Affect, appraisal, and consumer judgment. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(2):412-424. https://doi.org/10.1086/422119 [ Links ]

Zimmerman BJ 2008. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1):166-183. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0002831207312909 [ Links ]

Received: 17 April 2017

Revised: 22 May 2018

Accepted: 25 March 2019

Published: 31 May 2019