Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 no.2 Pretoria may. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n2a1534

ARTICLES

Perceptions of teachers and school management teams of the leadership roles of public school principals

Parvathy Naidoo

Department of Education Leadership and Management, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. pnaidoo@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

One of the reasons attributed to the continuous decline in student performance and low educational outcomes in public schools is the poor leadership displayed by many principals. Despite the fact that there are no stringent criteria for the appointment of school principals or prerequisite qualifications, principals do have the potential to lead and manage efficient and successful schools. In this paper, I argue that principals can develop exemplary leadership practices when subjected to sound training and professional development programmes. The Department of Education and Higher Education institutions have emphasised the importance of formal qualifications for enhancing career development programmes for practicing and aspiring principals in South Africa. Using questionnaires, I explore the perceptions of teachers and school management team (SMT) members of the leadership qualities exhibited by principals who acquired the professional qualification referred to as the Advanced Certificate in Education: School Leadership and Management (ACESLM). Findings revealed that leadership development for principals is crucial for school improvement because of active teaching and learning. Leadership capacity requires principals to participate with relevant stakeholders skilfully, and where there is high leadership capacity, instructional leadership develops into sound leadership practices.

Keywords: effective leadership; instructional leadership; leadership practices; professional development; school improvement; school leadership

Introduction and Background to the Problem

Several research studies accentuate the importance of principals taking on strong leadership roles in creating efficient and successful schools (Gunter, 2001:33). Principals usually perform three interchangeable functions at school level. As managers, they focus on managing and controlling human, physical, and financial resources. As leaders, they drive the vision of the institution and focus on organisational development and school improvement, while as administrators, they deal with day-to-day operational matters, and continuously shift between leadership and management functions (Kowalski, 2010:23). Moreover, the principal's role is one that is in a constant state of transition, moving from being an instructional leader (Abdullah & Kassim, 2011; DeMatthews, 2014; Mestry, 2017) to that of a transactional leader, who at times embraces the notion of a transformational leader (Balyer, 2012; Fullan, 1991, cited in Wondimu, 2014; Tingle, Corrales & Peters, 2019). Evans and Mohr (1999) asked a pertinent question, "Can principals' professional development truly improve practice?" Principals in the 21st century execute multi-faceted roles, their responsibilities are more demanding and challenging, at times complicated, overloaded and unclear according to Bush (2013); Mahlangu (2014); Mestry (2017) and Tucker and Codding (2002). These authors allude to a principal's day usually being filled with diverse managerial activities, such as scheduling, reporting, handling relations with parents and community, as well as dealing with unexpected multiple student and teacher crises and conflict. Additionally, Grant, Gardner, Kajee, Moodley and Somaroo (2010) claim that building a culture of accountability, mutual trust and respect among school leaders and staff is another mammoth task for school leaders. These authors therefore argue that the ultimate challenge for principals in the twenty-first century is not deciding whether to perform administrative duties, provide exemplary leadership, manage diverse staff, students and the school's curriculum, but rather for them to acquire the essential acuity and time to execute all of the above duties and functions optimally, and often, all at the same time. Good principals create successful schools, according to Kelley and Peterson (2007:355) and the Wallace Foundation (2008), by critically examining innovative ways to improve their schools by aiming to provide exemplary leadership. Shipman, Queen and Peel (2007:41) agree that effective school leaders understand their ultimate goal, which is to provide students and teachers with continuous learning opportunities. DeMatthews (2014) claims that principals become effective instructional leaders when they critically analyse existing curricula and the implications thereof for teachers' teaching strategies and student outcomes. Naidoo and Petersen (2015) argue that principals only become effective instructional leaders when they engage teachers with more culturally relevant teaching strategies and practices that result in improved student outcomes. Finally, most education scholars believe that principals are responsible for setting the tone of the school, by providing effective instructional leadership and ensuring the professional management of schools. These are however, fundamentally different jobs requiring different leadership practices, skills, and functions, according to Booth, Segon and O' Shannassy (2010), Chubb (2014) and Tingle et al. (2019).

With the advent of the South African Schools Act (Republic of South Africa, 1996), decision-making has been decentralised to the level of individual schools. Governing bodies have legitimate powers to regulate the administration of schools, while principals remain accountable for the professional management of the institution. Thus, according to Caldwell and Spinks (1992:4), self-managing schools would have placed more authority, accountability, and responsibility on principals to make decisions within a framework of goals, policies, and standards. It is expected that principals achieve sound educational outcomes and high student performances. However, in a South African context, some principals are not sufficiently ready for the principalship position, since they "are not appropriately skilled and trained for school management and leadership" (Mathibe, 2007:523).

Two crucial issues come to the fore. Firstly, there are no stringent criteria for the appointment of principals, except that the applicant should hold a teachers' diploma or degree, and have at least seven years teaching experience (Gauteng Department of Education, 2012). Secondly, there is no prerequisite professional qualification for aspiring teachers to take up principalship posts (Caldwell, Calnin & Cahill, 2003).

In South Africa, there is currently no overarching principal preparation or certification programme. In 2012, the Minister of Basic Education, Angie Motshega, recognised the need to review the policy on the appointment of principals in public schools (Mkhwanazi, 2012:4). The Minister proposed that applicants undergo competency tests before appointment into prin-cipalship positions. Competency tests, in her opinion, would strengthen the accountability of principals and ensure that only suitable candidates with appropriate skills to lead schools are hired (Prospective principals may have to take competency tests, 2011:2). However, teacher unions vehemently opposed this scheme, causing the Minister to defer the proposal. The importance of specific and specialised training and development for school principals has become the focus, according to Bush (2008).

Vigorous efforts to provide professional development programmes for practicing and aspiring principals are given high priority by the Department of Education (DoE). This particular need has been part of robust debates among educational leaders for the past decade (Van der Westhuizen & Van Vuuren, 2007). The importance of principals and other school managers, having the necessary leadership and management skills to manage schools effectively, was emphasised by the National Department of Education's Task Team (1996:16). The findings of the Task Team gave prominence to principals being equipped with the necessary skills and expertise to manage people, finances, and physical resources effectively, and to lead change and support the process of transformation. Initially, the DoE (2008) instituted the Advanced Certificate in Education (School Leadership and Management) (ACESLM) to improve the leadership and management skills and knowledge of school managers. More recently, the DoE attempted to raise the professional standards and competencies of school principals by formulating the South African National Professional Qualification for Principalship (SANPQP) (DoE, 2016). This policy identifies many fundamental principles that ought to inform a national professional qualification for existing and aspiring principals. Using the SANPQP to raise standards for the appointment of suitable principals, the DoE has reviewed its decision to make the ACESLM the entry-level qualification for aspiring principals. After that, the DoE is embarking on introducing the Advanced Diploma in Education: School Leadership and Management (ADESLM) as an entry level qualification for prospective principals. This matter is still under review among various stakeholders in education, and not yet legislated. However, many proactive institutions of higher learning in the country are preparing to implement this new qualification after the Higher Education Qualifications Committee (HEQC) has approved the qualification.

In this paper, I focus on how principals and other school managers benefitted from completing the ACESLM programme at tertiary institutions from the perceptions of deputy principals, heads of departments and post-Level One teachers of the leadership practices displayed by their principals who had completed the ACESLM course. This programme is designed from a South African leadership perspective, and focuses on module instruction in leadership and management, with emphasis on pedagogy; learning; finance; human resources; educational law; and educational policy. One of the goals of the course was to provide principals and other school managers with a sound knowledge base and rigorous intellectual ex-perience that would equip them to harness the human and other resources necessary to ensure highly effective educational institutions. This course enabled principals to develop insight into aspects that deal with school improvement, assessing school needs, shaping the strategic direction of the school, improving quality teaching and learning, implementing legislation and policy issues related to school education, empowering staff, and actively engaging themselves in the development of the school.

As a former principal, and having engaged within a network of many ACESLM graduates, the author agrees the ACESLM programme has indeed made a positive impact on principals' leadership and management practices. Bush, Duku, Glover, Kiggundu, Kola, Msila, Moorosi, Legong, Madimetja, Makatu, Maluleke and Stander (2012) and Msila (2010) argue that many school managers who completed the ACESLM qualification have made tangible improvements to their schools and they are leading efficient and successful schools. It is the intention of this study to corroborate the validity of this assertion through empirical research, conducted with respondents other than the ACESLM graduates. The research question that led this investigation is: What are the perceptions of teaching staff members (deputy principals, heads of department and post level-one teachers) of the leadership practices exhibited by the principals who completed the ACESLM course?

The following sub-questions further augment this:

· What is the nature and essence of continuing professional development?

· What international standards of principalship inform this study?

· How can practicing and aspiring school principals strengthen their leadership practices through formal professional development programmes such as the ACESLM?

The Rationale for This Study

The general aim of this research study was to determine the perceptions of deputy principals, heads of department, and post-Level One teachers of the leadership practices displayed by their principals who had completed the ACESLM course. As the ACESLM is largely practiced-based, the researcher's intention was to ascertain how much of the course learning was internalised, made meaning of, and discernable in practice. Hence the researcher chose respondents who worked at the same schools as principals, since they were best placed to respond to the items on the questionnaire.

The first objective of this study was to explain the nature and essence of continuing professional development within international standards. The second objective was to provide recommendations on how principals and other school managers can strengthen their leadership practices through formal development programmes.

Continuing Professional Development for Principals

According to Mathibe (2007), Mestry and Singh (2007) and Prew (2007), principals face the daily task of creating conducive learning environments in their schools. Support and intervention programmes to empower principals to lead and manage schools effectively are of paramount importance. Mestry and Singh (2007) assert that principals be provided with the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to enable them to cope with a dynamic and ever-changing educational environment. Earley and Bubb (2004:1-2) recognised this, and highlight that the training and development of principals should incorporate the fundamental differences between instructional leadership and managing schools into leadership development programmes, as delegated powers enable schools to become self-managing and increasingly autonomous. They concur with Fullan's (1997) techniques of inquiry, and consider leadership development programmes as a mutual and interactive investment in growth and development for all parties concerned. The three most important dimensions of leadership de-velopment and overall school improvement are the ability to reflect, inquire and facilitate dialogue among all stakeholders. Principals draw from effective school leadership practices in order to address essential questions concerning problems of practice relating to management issues, and teachers' teaching and students' learning. There-fore, leadership development programmes ought to be structured to address significant issues related to principal and teacher effectiveness and student learning, thereby improving the school and the district's goal for overall school improvement and student learning (Moorman, 1997).

For maximum benefit, leadership development programmes need to be undertaken from an organisational perspective because linking leadership development programmes to educational leadership give rise to two forms of socialisation (Crow, 2003:2). The first form is the learning of a new professional role. The second is the performance of this role within new organisational situations. Crow (2003) proposes that the two forms of socialisation are interconnected, as preparing for a new role in a new context should share equal importance for maximum value. Therefore, the individual's development and the achievement of organisational goals should be synchronised (Heystek, 2007:491-494; Mestry & Grobler, 2002:21). Marczely (1996) argues that principals play an additional role - that of a primary staff developer, since they have the greatest direct control over the teaching and learning environment and student achievement in schools. Principals create the context in which professional development is either encouraged or suppressed according to Marczely (1996).

Several researchers (Barrett & Breyer, 2014; Tingle et al., 2019) claim that school principals play the roles of curators and custodians of their school's vision, mission and values, as they provide the inspiration to achieve the school's vision and mission by directing people towards that chosen destination. As a result, they are required to demonstrate certain leadership qualities to achieve and maintain quality schools in complex environments. Such complex situations also imply that school leaders should be equipped with "multi-faceted skills" (Vick, 2004:11-13), which are pre-requisites for successful leadership. The "How Leadership Influences Learning" report by the Wallace Foundation (2008:1) makes the point that there "are virtually no documented instances of troubled schools being turned without intervention by a powerful leader. Many other factors may contribute to such turnarounds, but leadership is the catalyst."

Schools only become effective when professional learning communities that focus on student performance emerge, resulting in changes in leadership and teaching practices. Any school that is trying to improve has to consider pro-fessional development for principals as a cornerstone strategy (Fullan, 2003:5) because principals play a central role in orchestrating school reform and improvement, according to Kelley and Peterson (2007:351). The reform and improvement is only possible through appropriate leadership development programmes that enable principals to initiate, implement, and sustain high-value schools that provide quality education. This important role compels leadership development to include relevant superior training to enable principals to serve strategic functions in organisational leadership, and to engage robustly with all stakeholders so that schools become centres of meaningful learning.

The broader literature indicates that leadership embraces three relevant variables (Ivancevich & Matteson, 2002), namely: the people that lead; the task at hand; and the environment in which the people and their responsibilities co-exist. These variables present differently in different situations, while the expectations and requirements from leaders differ significantly from situation to situation. As a result, the challenges facing leadership become vast and complicated. Only leaders with established value systems reflecting integrity, fairness, justness, and respect (Ivancevich & Matteson, 2002:425) can cope with challenging and incongruent situations.

Bush (2003:170) notes that a robust moral leadership based on, "values, beliefs and ethics" is necessary when examining leadership. Covey (2004:98) claims that leadership is "communicating to people their worth and potential so clearly, so powerfully and so consistently that they come to see it in themselves." Covey (2004:217) also mentions, the creation of an environment that makes "people want to do, rather than have to do," is only possible when leadership in an organisation gives "purpose and value to the people they work with and lead." Therefore, leadership in any institution/organisation ought to be grounded in a firm personal and professional values system, within an environment that encourages active participation of all within the organisation. Fullan (2003) makes the argument that leadership is only efficient when it provides a sustainable direction for any organisation, and leaders cannot be leaders if they have no followers (Lambert, 2003; Mills, 2005). Effective leaders have the ability to analyse situations professionally and skilfully, and to search for ways to make their organisations grow. Having sound character traits, while showing attributes such as leadership competency and honesty when executing responsibilities is indicative of dynamic leadership. Accordingly, leaders need to embrace the factors of leadership that entail being a follower, a leader, and a communicator in any situation that may arise. An effective leader is one who is proficient, encourages teamwork, and team spirit, and ar-ticulates a clear, concise vision of the organisation to his followers by providing direction that is supported by sound and timely decisions taken for the sole purpose of improving the institution.

A Global View of School Leadership Development

Many countries, such as Singapore, England, Scotland, New Zealand, Sweden and the United States of America (Bush, 2010:266) require principals to have acquired a formal qualification in school administration and or leadership. I briefly describe the professional development or prerequisites for principalship of the following countries.

In Singapore, aspiring principals are required to obtain their Diploma in Educational Administration (DEA), before appointment as principals. The programme is full-time for one year, and the Education Ministry selects the participants. England launched the National Professional Qualification for Headship (NPQH) in 1997 to address the professional development needs of aspiring and practicing principals (Bolam, 2003:81, Caldwell et al., 2003:111, Ribbins, 2003: 174). The focus was on an accredited training programme, which suits the needs of the modern principal, and it is firmly rooted in school improvement. The Standard for Headship in Scotland served as a valuable tool in constructing a qualification for all candidates who aspired to become principals (Reeves, Forde, Morris & Turner, 2003:57). The Scottish Qualification for Headship (SQH), a practice-based programme, was developed, requiring candidates to consider their professional values, their performance of the functions of school management, and the abilities they need to carry out all management and leadership functions effectively. The model used for leadership development in New Zealand comprises a different structure compared to other countries, where an estimated 180 first-time principals are hired into new principal positions each year. In 2001, the Ministry of Education of New Zealand introduced a three-phase induction programme for all principals (Martin & Robertson, 2003:2-3). In Sweden, the local board of education selects head teachers (school principals) after they have gone through a rigorous recruitment programme (Caldwell et al., 2003:126). The recruitment programme identifies qualities that are suitable for head teachers.

By implication, leadership development programmes, internationally, serve as prerequisites for the appointment to the post of a school principal, and this is unfortunately not the case in South Africa.

Research Methodology and Design

This study formed part of a larger research investigation in which the researcher used a mixed method sequential, exploratory approach. Phase One dealt with the collection of qualitative data from ACESLM graduates, followed by Phase Two, where quantitative data was collected from teachers, heads of department and deputy principals, who worked in the same schools as the graduates. The researcher was able to mix qualitative and quantitative research methods, procedures and paradigm characteristics meaning-fully in addressing the research questions (Johnson & Christensen, 2004). Hence, the analysis of the qualitative investigation and literature review led to the development of a questionnaire, administered in the quantitative study. In this paper, the researcher discusses only the quantitative phase of the research.

According to Maree and Pietersen (2007), quantitative research strives for objectivity in the manner that numerical data from a population is used to generalise the findings to the phenomena under study. The population of this study comprises one of the universities located in the Gauteng Province that implemented the ACESLM since 2004, where over 1,000 students had graduated from this programme.

The researcher used stratified random sampling to identify and select 600 respondents (consisting of deputy principals, heads of department and post level-one teachers) at the 120 selected schools where ACESLM graduates were principals. They were naturally appropriate for this investigation. A questionnaire was administered to determine the perceptions of respondents of the leadership practices of their school principals who had completed the ACESLM qualification. Only SMT members and teachers who had two or more years working experience with their principals were chosen to participate in this study.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. Section A comprised nine items that required biographical data of the respondents. Section B consisted of 20 closed-ended questions that dealt with perceptions of deputy principals, heads of departments and post level-one teachers regarding their principal's execution of critical leadership practices. Respondents were required to rate the statements according to whether they believe that their principals were able to implement leadership practices and actions. Section C comprised 18 closed-ended questions depicting factors that may have compromised or hindered the principals' ability to apply and sustain leadership practices and actions in their schools. A five-point Likert scale asked respondents to rate statements according to whether they believe the factors compromised or hindered the principals from practicing leadership skills. In addition, Section C included one open-ended question, where respondents had the choice of listing other factors that may have compromised or hindered their principals' ability in the implementation of their leadership practices.

A pilot study enhanced the validity of the instrument (Creswell, 2008). Pretesting of the questionnaire with 20 randomly selected respondents consisting of deputy principals, heads of departments and post level-one teachers from the selected 120 schools where principals had completed the ACESLM qualification was undertaken. To ensure that every item in the questionnaire was clear and unambiguous comments and suggestions made by respondents resulted in some items being deleted or rephrased. Lastly, appropriate adjustments to the research instruments were made on the advice of statisticians of the University.

The quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The items of the questionnaire were subjected to statistical analysis and factor analysis procedures using the Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW) Statistics 18 computer software programme (Norusis, 2010). The researcher used descriptive and inferential numeric analyses to analyse the data (Creswell, 2009). All items were rated by respondents on a scale of one to five, with one being the lowest rank (not important at all), to five being the highest (very important), as well as one being the lowest rank - "to no extent" - and five being "to a very large extent."

Permission to conduct research was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University. The Gauteng Department of Education approved the application to conduct research in schools located in various districts under their jurisdiction. Written permission was obtained from all the principals and School Governing Bodies (SGB) of the participating schools. Respondents were aware that information provided was confidential and their anonymity assured at all times. Their participation in the study was voluntary, and permission given to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Concerning the collection of the completed questionnaires, I identified and engaged field workers who visited the various research sites to collect the completed questionnaires. Six hundred questionnaires were distributed to deputy principals, heads of department and post level one teachers and 486 (81%) were returned and considered usable.

Discussion and Findings

In Section A of the questionnaire, the sample representation showed that most of the respondents surveyed were post level-one teachers (N = 354), which represented 72.8 % of the population studied. Heads of Department (N = 101) and Deputy Principals (N = 31) represented 20.8% and 6.4% respectively. The larger percentage of respondents (57.6%) were female, and 42.4% were male. This sample, in my view, is in keeping with the gender representation of the country's public school teaching sector, where female teachers dominate the profession. The largest home language group was Nguni (N = 267), followed by the English/Afrikaans (N = 139) language group. The Sesotho language group featured at 16.4 percent. The biographical details of respondents further revealed that most of them had acquired postgraduate qualifications (N = 279). A high percentage of those surveyed (74.7%) belonged to the South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU) and the rest belonged to smaller teacher unions, such as the National Union of Educators (NUE), and the Suid-Afrikaanse Onderwys Unie (SAOU). In the analysis discussed later, the author observed that the affiliation of teachers and SMT members to some teacher unions is a factor that hindered or compromised the principals' leadership practices.

Analysis and Discussion of Items in Section B of the Questionnaire

Those items associated with the principals' implementation of leadership practices perceived by the teachers, heads of department and deputy principals selected and henceforth referred to as "others."

Section B items/questions were formulated in a way that required the respondents to indicate the extent to which they believed that their principals were able to implement the leadership practices, tasks, and/or actions. For example, the respondents were asked:

To what extent do the principals:

Exhibit qualities of an educational leader, who can maintain a purposeful interaction among the school's stakeholders.

Three items are selected for discussion (ranked 1 (item 11), 10 (item 19) and 20 (item 2)) using relevant data relating to the category 'Implementation of leadership practices' from the perspective of "others" as indicated in Tables 1 and 2.

Item B11: Ensure that all staff members are responsible for creating a positive learning climate in the school

This item had a mean score of 3.98 and had a rank order of one. The analysis showed that 73.0% of respondents largely agreed that their principals ensured that all staff members were responsible for creating a positive learning climate in the school. The mean score of 3.98 also showed agreement largely.

Item B19: Ensure that the school finance committee is familiar with the legal framework required to formulate the financial policy of the school

The Item ranked tenth with a mean score of 3.91, which revealed that 70.2% of respondents agreed largely that their principals ensured the school finance committee, is familiar with the legal framework required to formulate financial policy. The researcher's assumption is that respondents view leadership practices incorporating the legal framework in education and school finances as integral components in schools.

Item B2: Use different leadership strategies to get the best teaching and learning efforts from my staff

This item ranked the lowest, with a mean score of 3.72. Analysis showed that 64.7% of respondents agreed to a moderate extent that their principals used different leadership strategies to get the best out of their staff. The largest number of respondents (N = 354 - "others") are level-one teachers. The school management teams (SMT, heads of department and deputy principals) count (N = 132) was significantly smaller. The im-plication is that the exposure of teachers to their principal's leadership strategies can be considered limited, as heads of department and deputy principals (and not post level teachers) liaise more frequently with their principals. The reason that most teachers simply have insufficient knowledge of how their principals lead schools to provide accurate assessments.

In the ACESLM (DoE, 2008) curriculum taught at the university, the above are emphasised in engaging with the modules on Managing Teaching and Learning, Leadership and Managing Education Law and Policy. Thus, principals who had completed the ACESLM course are more likely to be effective and successful, for example, in ensuring that staff members create a positive learning climate in the school.

Analysis and Discussion of Items in Section C of the Questionnaire

Selected items that hindered or compromised principals from implementing and sustaining the leadership practices

Items in Section C of the questionnaire were formulated in such a way that the respondents were required to indicate the extent to which they believed that their principal's leadership practices were compromised or hindered and these are reflected in Tables 3 and 4.

Item C22: Staff's affiliation to teacher union

The analysis revealed that only 45.1% of the respondents agreed to a large or very considerable extent that their principals' leadership practices were compromised by the staff's affiliation to teacher unions. This item ranked first, with a mean score of 3.27. The author is of the view that the affiliation itself is not the problem, but rather, the activities arranged by the unions during learner contact time that posed serious challenges to effective teaching and learning to take place in schools. The researcher, a former principal, supports this claim as union meetings convened during learner instructional time require school management teams to make alternate arrangements for substitute teachers to oversee lessons. This practice interrupts the normal functioning of the school.

Item C29: Absence of assertive action on the part of the principal

The analysis revealed that 28.3% of the respondents (total N = 477) noted the lack of assertive action on the part of their principals. This item ranked number ten, with an average score of 2.75, which indicated a moderate agreement with the statement. The author's assumption is that the words "assertive action" were not specific enough to elicit accurate responses from the respondents. The term "assertive action" could include too many possible actions, such as not implementing departmental mandates, or not holding teachers accountable for poor learner results or not dealing decisively with staff misconduct.

Item C34: Recruitment of unsuitable staff

The item's mean score of 2.56, ranked eighteenth. Only 19.7% of the respondents largely agreed that recruiting inadequate staff had compromised the principals' leadership practices. Although the ACESLM curriculum covers the wide field of educational leadership and management and provides principals with relevant knowledge and skills, the effective application of the knowledge and skills is inevitably dependent on the principals and the contexts in which they operate. Principals who are not assertive are more likely to yield to the pressures of unions and governing bodies, according to the respondents.

Discussion of one open-ended question in Section C of the questionnaire

Section C of the questionnaire consisted of one open question, which invited the respondents' views regarding other factor/s that may have compromised or prevented the respondents' principals from implementing and sustaining the leadership practices and responses are reflected in Table 5.

The responses seem, overall, to be honest, and forthright, and the respondents suggest the presence of "challenges" that influence the principal's ability to implement leadership practices. These challenges range from administrative malpractices in schools, unsuitable organisational systems and processes, inconsistent teacher workloads, staff shortages, insufficient resources, poor infrastructure and improper recruitment of school leaders. The respondents' perceptions varied significantly, whilst some respondents alluded to their principals doing their utmost to improve their schools, others were resolute about the fact that their principals were "not fit" to lead and manage schools. What was clear is that self-interest may have played a bigger part than one thinks it did. While some respondents were brazen in their responses, others may have hidden their true feelings where they felt, it would be against their interest to reveal information in an open and honest way.

Inferential Analysis

Inferential analysis of the data of "others" (deputy principals, heads of department [HODs], and teachers)

Section B of the questionnaire consisted of 20 questions, for the "others" from differing post levels regarding the extent to which they believed that their principal could implement leadership practices. A Principal Factor Analysis (PFA) procedure was followed and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) = 0.961; p = 0.000 indicated that a factor analysis was feasible. A varimax rotation resulted in two first-order factors explaining 57.76% of the variance resulted.

A Monte Carlo parallel analysis also indicated that two factors are feasible. A second-order procedure with KMO = 0.500 and p = 0.000 led to one factor containing 20 items with an Alpha Cronbach Reliability coefficient of 0.951, which explained 90.8% of the variance present and was named "educator perceptions of the implementation of leadership practices" indicated in Figure 1.

A mean score of 3.88 indicated that teachers tend to agree, for the most part, that the principals in their schools can implement the leadership practices. The data distribution skewed negatively, but since the sample was large enough, parametric statistical procedures were used.

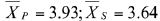

When primary school respondents' and secondary school respondents' mean scores regarding their principals' implementation of lead-ership practices were compared, it was found that the former respondents had an average score that was statistically significantly higher than their secondary school counterparts were  . The high school respondents agreed to a statistically significant smaller extent that their principals could implement leadership practices than do primary school respondents. I argue that this difference is possibly due to greater disciplinary problems faced in secondary schools and the more significant differentiation regarding the curriculum.

. The high school respondents agreed to a statistically significant smaller extent that their principals could implement leadership practices than do primary school respondents. I argue that this difference is possibly due to greater disciplinary problems faced in secondary schools and the more significant differentiation regarding the curriculum.

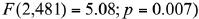

Since teachers, HODs, and deputy principals answered this questionnaire, the author reasoned that the deputy principals knew more about the implementation issues than did the other teachers. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test was conducted to see whether the perceptions of the various post level groupings differed. The appropriate values when comparing three independent groups are  . This indicated that when the three post-level groups were compared, there was a significant difference between the groups. The Dunnett T3 test indicated that the factor means of both HODs and teachers differ statistically significantly from one another

. This indicated that when the three post-level groups were compared, there was a significant difference between the groups. The Dunnett T3 test indicated that the factor means of both HODs and teachers differ statistically significantly from one another  . The linear relationship [F (1.481) = 7.67; p = 0.006] between post-level and extent of agreement as shown in Figure 2.

. The linear relationship [F (1.481) = 7.67; p = 0.006] between post-level and extent of agreement as shown in Figure 2.

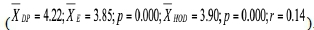

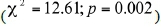

The author found that deputy principals agreed largely that their principals are im-plementing leadership practices. A cross-tabulation of schools and post-levels indicated that there were significantly more (24) primary school deputy principals in the sample and significantly fewer deputy principals (two) in the secondary school than expected  . I argue that the difference is probably due to the perceptions of the deputy principals involved in the sample. They would understand the difference between the importance of the leadership practices, as well as between importance and implementation of leadership practices. The researcher expected this result, as one is comparing the ideal with the reality of implementation, where many can consider implementation harder than the espoused importance. The effect size (r = 0.58) enables one to determine the importance of principals im-plementing leadership practices in public schools.

. I argue that the difference is probably due to the perceptions of the deputy principals involved in the sample. They would understand the difference between the importance of the leadership practices, as well as between importance and implementation of leadership practices. The researcher expected this result, as one is comparing the ideal with the reality of implementation, where many can consider implementation harder than the espoused importance. The effect size (r = 0.58) enables one to determine the importance of principals im-plementing leadership practices in public schools.

Section C consisted of 18 items and respondents provided their opinions as to the extent to which certain aspects prevented their principals from practicing their leadership skills. The 18 questions elicited a PFA with KMO = 0.955; p = 0.000 and indicated that the procedure would result in the items forming factors. However, as C22 had a communality < 0.3, it was removed from the analysis. Item C22 asked whether staff affiliation to teacher unions compromised the principal's ability to implement leadership practices, and it seemed peculiar, in the light of the problems experienced with teacher unions, specifically with The South African Democratic Teacher's Union (SADTU), that the items showed so little communality with the other items. It is possible that the affiliation, as such, does not compromise leadership practices and that the wording of the item on the questionnaire should have been different, for example, "interruptions in teaching and learning due to union meetings held during learner instructional time."

The remaining 17 items had a KMO = 0.955 and Bartlett's sphericity of p = 0.000 indicating that factor analysis was plausible. The second-order procedure resulted in only one factor, named "Aspects that compromise the principal from practicing leadership skills." It contained 17 items, had a Cronbach's Alpha reliability coefficient of 0.952, and explained 88.51% of the variance present. The mean score of 2.2 indicated that the respondents believed that the aspects listed only compromised their principals' ability to implement leadership practices in their schools to a small extent.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Literature, both national and international, shows that principals, when appointed into leadership positions experience great difficulty in adapting to the demands and expectations of the role they are required to execute (Du Plessis, 2017; Huber, 2004; Mathibe, 2007; Mestry, 2017; Tingle et al., 2019). What is clear is that principals need specialised leadership preparation, with continuous pro-fessional development. Studies conducted by Heystek (2007), Mestry and Singh (2007) and Msila (2010) found that ACESLM as a leadership development programme for school leadership in the South African context has merit. Other studies by Bush, Duku, Glover, Kiggundu, Kola, Msila and Moorosi (2009) and Bush et al. (2012) revealed that the ACESLM qualification as a leadership development programme was highly favourable for all members of the school management teams, as well as for post level-one teachers.

This study places principals who have completed the ACESLM course on a favourable career trajectory in leadership and management development and practice. Through the acquisition of the ACESLM course, they acquired largescale knowledge, attributes and skills in leadership and management areas. The perceptions of the deputy principals, HODs and post level one teachers were mainly positive, principals' leadership practices were enhanced significantly.

A pertinent question arises as to whether it is incumbent for all practicing school leaders to complete a qualification such as the ACESLM, or one that is similar in structure, design, and delivery? This study recognises the value of ACESLM as a leadership development programme for school leaders. Moreover, in the absence of a prerequisite qualification for entry level for principalship in South Africa, continuous leadership development for school leaders becomes crucial. Twenty-first century principals are required to develop and maintain healthy relationships with all stakeholders, ensuring that effective teaching and learning being the "core business" of schools take place. Principals also manage resources efficiently, and additionally, are required to make sure that legislation and education policies are implemented fastidiously.

"Leadership capacity" is broad-based (Lambert, 2002), requiring the skilful participation of the relevant stakeholders, and where there is high leadership capacity, learning and instructional leadership become infused into sound professional leadership practices. This study underscores the value of school leaders completing the ACESLM course, and this may be an appropriate relevant point of departure for all aspiring and practicing principals. But the course alone will not be sufficient, as principals daily encounter a myriad of challenges that require innovative strategies to lead and manage transforming schools. It is only through continuing professional leadership development and practical experience, together with the application of appropriate skills, informed knowledge, values, and attitudes that successful schools will emerge.

The author therefore strongly recommends that the Department of Basic Education seriously consider introducing a prerequisite qualification, comprising of a similar structure to the ACESLM for all aspiring principals for appointment to a principalship position. Additionally, this quali-fication ought to be taken by all school management teams within the first two years of their appointment into management positions. Lastly, the qualification should be made accessible to all practicing SMT members as part of their mandatory continuing professional development.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Abdullah JB & Kassim JM 2011. Instructional leadership and attitude towards organizational change among secondary school principals in Pahang, Malaysia. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15:3304-3309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.290 [ Links ]

Balyer A 2012. Transformational leadership behaviors of school principals: A qualitative research based on teachers' perceptions. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 4(3):581-591. Available at http://www.acarindex.com/dosyalar/makale/acarindex-1423904284.pdf. Accessed 19 January 2019. [ Links ]

Barrett C & Breyer R 2014. The influence of effective leadership in teaching and learning. Journal of Research Initiatives, 1(2): Article 3. Available at http://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/jri/vol1/iss2/3. Accessed 20 February 2018. [ Links ]

Bolam R 2003. Models of leadership development: Learning from international experience and research. In M Brundett, N Burton & R Smith (eds). Leadership in education. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Booth C, Segon, M & O' Shannassy T 2010. The more things change the more they stay the same: A contemporary examination of leadership and management constructs. Journal of Business and Policy Research, 5(2):119-130. [ Links ]

Bush T 2003. Theories of educational leadership and management (3rd ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Bush T 2008. Leadership and management development in education. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Bush T 2010. Editorial: The significance of leadership theory. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(3):266-270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210362304 [ Links ]

Bush T 2013. Editorial. Leadership development for school principals: Specialized preparation or post-hoc repair? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(3):253-255. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1741143213477065 [ Links ]

Bush T, Duku N, Glover D, Kiggundu E, Kola S, Msila V & Moorosi P 2009. External evaluation research report of the Advanced Certificate in Education: School leadership and management. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Education. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.233.2550&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 22 January 2019. [ Links ]

Bush T, Duku N, Glover D, Kiggundu E, Kola S, Msila V, Moorosi P, Legong P, Madimetja K, Makatu S, Maluleke J & Stander R 2012. The impact of the National Advanced Certificate in Education: Programme on school and learners' outcomes (School leadership and management research report). Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Caldwell B, Calnin G & Cahill W 2003. Mission possible? An international analysis of headteacher/principal training. In N Bennett, M Crawford & M Cartwright (eds). Effective educational leadership. London, England: Paul Chapman. [ Links ]

Caldwell BJ & Spinks JM 1992. Leading the self-managing school. London, England: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Chubb J 2014. Building a better leader: Lessons from new principal leadership development programs. Available at https://edexcellence.net/articles/building-a-better-leader-lessons-from-new-principal-leadership-development-programs. Accessed 22 January 2019. [ Links ]

Covey SR 2004. The eight habit: From effectiveness to greatness. New York, NY: Free Press. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2008. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Crow GM 2003. School leader preparation: A short review of the knowledge base. Nottingham, England: National College for School Leadership. Available at http://www3.nccu.edu.tw/~mujinc/teaching/9-101principal/refer1-1(randd-gary-crow-paper).pdf. Accessed 20 March 2016. [ Links ]

DeMatthews DE 2014. How to improve curriculum leadership: Integrating leadership theory and management strategies. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 87(5):192-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2014.911141 [ Links ]

Department of Education, South Africa 1996. Changing management to manage change in education (Report of the Task Team on Education Management Development). Pretoria: Author. Available at https://edulibpretoria.files.wordpress.com/2008/01/changingmanagement.pdf. Accessed 4 February 2019. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2008. Advanced Certificate: Education (School Management and Leadership). Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2016. South African National Professional Qualification for Principalship (SANPQP) (Concept paper, September). Directorate: Education Management and Governance Development. [ Links ]

Du Plessis P 2017. Challenges for rural school leaders in a developing context: A case study on leadership practices of effective rural principals. KOERS - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 82(3):1-10. https://doi.org/10.19108/koers.82.3.2337 [ Links ]

Earley P & Bubb S 2004. Leading and managing continuing professional development: Developing people, developing schools. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Evans PM & Mohr N 1999. Professional development for principals: Seven core beliefs. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(7):530-532. [ Links ]

Fullan M 1997. The new meaning of educational change (2nd ed). London, England: Teacher's College Press. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2003. Leadership and sustainability. Plaintalk: Newspaper for the Center for development and Learning, 8(2):1-5. [ Links ]

Gauteng Department of Education 2012. Vacancy list 2012, as per collective agreement 2/2005, based on ELRC 5/1998, page 3. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Grant C, Gardner K, Kajee F, Moodley R & Somaroo S 2010. Teacher leadership: A survey analysis of KwaZulu-Natal teachers' perceptions. South African Journal of Education, 30(3):401-419. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v30n3a362 [ Links ]

Gunter HM 2001. Leaders and leadership in education. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Heystek J 2007. Reflecting on principals as managers or moulded leaders in a managerialistic school system. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):491-505. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/109/36. Accessed 16 January 2019. [ Links ]

Huber SG 2004. School leadership and leadership development: Adjusting leadership theories and development programs to values and the core purpose of school. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(6):669-684. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230410563665 [ Links ]

Ivancevich JM & Matteson MT 2002. Organizational behavior and management (6th ed). Chicago, IL: Mc Graw-Hill. [ Links ]

Johnson B & Christensen L 2004. Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (2nd ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Kelley C & Peterson KD 2007. The work of principals and their preparation: Addressing critical needs for the twenty-first century. In M Fullan (ed). The Jossey-Bass reader on educational leadership (2nd ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Kowalski TJ 2010. The school principal - Visionary leadership and competent management. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Lambert L 2002. A framework for shared leadership. Educational Leadership, 59(8):37-40. [ Links ]

Lambert L 2003. Leadership capacity for lasting school improvement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Links ]

Mahlangu VP 2014. Strategies for principal-teacher development: A South African perspective. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20):1378-1384. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1378 [ Links ]

Marczely B 1996. Personalizing professional growth. Staff development that works. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Maree K & Pietersen J 2007. The quantitative research process. In K Maree (ed). First steps in research. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Martin J & Robertson JM 2003. The induction of first-time principals in New Zealand. New Zealand - A programme design. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning. Available at http://iejll.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/iejll/index.php/ijll/article/view/411/73. Accessed 1 February 2019. [ Links ]

Mathibe I 2007. The professional development of school principals. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):523-540. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/111/38. Accessed 15 January 2019. [ Links ]

Mestry R 2017. Empowering principals to lead and manage public schools effectively in the 21st century. South African Journal of Education, 37(1): Art. # 1334, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n1a1334 [ Links ]

Mestry R & Grobler BR 2002. The training and development of principals in the management of educator. International Studies in Educational Administration, 30(3):21-34. [ Links ]

Mestry R & Singh P 2007. Continuing professional development for principals: A South African perspective. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):477-490. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/112/35. Accessed 15 January 2019. [ Links ]

Mills DQ 2005. The importance of leadership: How to lead, how to live? Waltham, MA: MindEdge Press. [ Links ]

Mkhwanazi S 2012. Principal's recruitment system undergoes review. The New Age, 12. [ Links ]

Moorman H 1997. Professional development of school principals for leadership of high performance learning communities (Preliminary report of the Danforth Foundation Task on Leadership of High Performance Learning Communities). [ Links ]

Msila V 2010. Rural school principals' quest for effectiveness: Lessons from the field. Journal of Education, 48:169-189. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vuyisile_Msila/publication/233881693_Rural_school_principals'_quest_for_effectiveness_lessons_from_the_field/links/0fcfd50c8209fa48b7000000.pdf. Accessed 14 January 2019. [ Links ]

Naidoo P & Petersen N 2015. Towards a leadership programme for primary school principals as instructional leaders. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 5(3): Art. #371, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v5i3.371 [ Links ]

Norusis MJ 2010. PASW statistics 18 guide to data analysis. Chicago, IL: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Prew M 2007. Successful principals: Why some principals succeed and others struggle when faced with innovation and transformation. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):447-462. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/115/33. Accessed 14 January 2019. [ Links ]

Prospective principals may have to take competency tests 2011. Saturday Star, 19 November. [ Links ]

Reeves J, Forde C, Morris B & Turner E 2003. Social processes, work-based learning and the Scottish qualification for headship. In L Kydd, L Anderson & W Newton (eds). Leading people and teams in education. London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. South African Schools Act, 1996 (Act No. 84, 1996). Government Gazette, 377(17579):1-50, November 15. [ Links ]

Ribbins P 2003. Preparing for leadership in education: In search of wisdom. In N Bennett & L Anderson (eds). Rethinking educational leadership: Challenging the conventions. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Shipman NJ, Queen JA & Peel HA 2007. Transforming school leadership with ISLLC and ELCC. New York, NY: Eye on Education. [ Links ]

Tingle E, Corrales A & Peters ML 2019. Leadership development programs: Investing in school principals. Educational Studies, 45(1):1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2017.1382332 [ Links ]

Tucker MS & Codding JB 2002. The principal challenge: Leading and managing schools in an era of accountability. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen P & Van Vuuren H 2007. Professionalising principalship in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):431-445. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/118/32. Accessed 13 January 2019. [ Links ]

Vick RC 2004. Use of SREB leadership development framework in preservice principal preparation programs: A qualitative investigation (Electronic theses and dissertations. Paper 932). Johnson City, TN: East Tennessee State University. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.898.4139&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 30 June 2015. [ Links ]

Wallace Foundation 2008. Becoming a leader: Preparing school principals for today's schools. New York, NY: Author. [ Links ]

Wondimu O 2014. Principal instructional leadership performances and influencing factors in secondary schools of Addis Ababa. MA thesis. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University. [ Links ]

Received: 25 May 2017

Revised: 3 July 2018

Accepted: 4 February 2019

Published: 31 May 2019