Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.38 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n3a1577

ARTICLES

The Circuit Managers as the weakest link in the school district leadership chain! Perspectives from a province in South Africa

Bongani D. BantwiniI; Pontso MoorosiII

IFaculty of Education, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa bongani.bantwini@gmail.com

IICentre for Education Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom and University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The role of circuit managers is an essential component of school district leadership, which provides a necessary bridge between schools and government. School districts play a vital role in continuously collaborating, guiding and leading, and challenging schools to raise standards. In this paper, we draw on a subset of semi-structured interviews with education leaders in the Eastern Cape province, on their perspectives on the circuit management role. From these interviews, circuit managers were labelled as the 'weakest link' in the educational leadership chain. We explore the cause, nature and the extent to which circuit managers are perceived to be the weakest link and the implications thereof. Our discussion engages various factors that lead to Circuit Managers being considered the weakest link in the education leadership chain and these include: poor circuit office structure, the high vacancy rate of Circuit Managers, and external interference. We argue for the strengthening of the Circuit Offices and suggest ways in which they could be utilised to add more value in the efforts to improve the quality of basic education in the public schools.

Keywords: circuit managers; district officials; educational leadership; school district; South Africa

Introduction

School district leadership provides a critical link between most educational reform initiatives and their consequences for student achievement by bridging the interaction between schools and the provincial government. According to Marzano and Waters (2009), district leadership has an indirect but an important effect on student achievement, a view that is supported by Christie, Sullivan, Duku and Gallie (2010) as they posit the existence of a relationship between quality education in schools and the quality of leadership at the Education District Office level. Attesting to this notion, Marzano and Waters (2009) argue that high functioning districts influence what happens in the classrooms, which in turn influences student achievement. Moorosi and Bantwini (2016) view the significance of district leadership in improving schools and student learning as central to driving educational reforms and achieving greater educational quality in the emerging economies. However, in South Africa, it is arguable that contextual factors in some districts can work against the best leadership efforts (Bantwini & Diko, 2011). These contextual factors include the lack of resource materials and infrastructure, lack of human capacity, lack of clarity on mandates, procedures and policies, to mention a few.

This paper is part of a larger study that focused on districts and their support of schools in the Eastern Cape province. In this larger study, a striking finding emerged as participants perceived circuit managers to be the weakest link in the provincial educational leadership chain. In this paper, we explore this perception and discuss the nature and extent to which Circuit Managers are considered the weakest link in the education leadership chain. This claim raised concerns but more importantly it also awakened an interest that warranted further and deeper investigation into the issue. To guide the discussion, we ask the following questions: (1) What are the factors that lead to the perception of Circuit Managers being seen as the weakest link in the district leadership chain? (2) How can Circuit Managers and their Offices be strengthened in order to provide a stronger link in the education chain? We view the centrality of the Circuit Managers as inevitable to an effective school district leadership chain. This study therefore intends to add to local and global discussions about the significance of a strong district-wide approach to leadership, as the neglect of one part can retard progress, or indeed lead to failure across the entire system.

Synopsis on the Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Education

The Eastern Cape (EC) Provincial Department of Education (PDE) is the head office of the education in the province. The PDE reports directly to the Department of Basic Education (DBE) headed by the South African Minister of Education. In terms of the education hierarch, the DBE is the national department responsible, among the key functions, for policy making. Then the policies are cascaded to the various PDE's for implementation. The PDE's collaborate with the education districts and then the circuit offices that directly work with the schools.

During the data collection period in 2016, the EC PDE consists of three district clusters (clusters A, B & C) each headed by a Chief Director. Each cluster is made up of several education districts,i totalling 23 in the province. The districts are headed by a District Director, who is tasked with executing the prescribed functions using authority delegated by the Head of the PDE (DBE, Republic of South Africa, 2013). Each school district is further divided into circuits, headed by the Circuit Managers (CMs). According to the DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013) policy on the organisation, roles and responsibilities of education districts, an education circuit is the second-level administrative sub-division of a Provincial Education Department. It is the management sub-unit of a district responsible for the Department of Basic Education institutions in its circuit. Aptly put, it is the field office of the district office and the closest point of contact between schools and the PDE.

According to the DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013:25) policy, the role of the Circuit Manager is therefore to execute prescribed functions allocated by the district director or the Head of the province. The Circuit Managers are the representatives of the district director, and therefore are expected to exercise significant authority in their dealings with their own circuit office staff, school principals, chairpersons of School Governing Bodies (SGBs) and the public at large. The Circuit Offices have a special responsibility to advise and support schools that are performing poorly and are therefore most in need of its service. Amongst other things, Circuit Offices are expected to provide management support and administrative services to schools and facilitate training for principals, school management teams and SGBs (DBE, Republic of South Africa, 2013). Clearly, the role played by the Circuit Managers and their office is fundamental in ensuring good quality basic education in schools hence the focus of this paper. This is a crucial role, as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development ([OECD], 2012:3) argues that school failures penalise a child for life, and that educational failure imposes high costs on society as poorly educated people limit economies' capacity to produce, grow and innovate. Investigations regarding the leadership mandated to ensure the success of schools is therefore of significant value, hence the rationale for this study.

Theoretical Framework: A Systems Thinking Approach to Leadership

This paper is premised on our belief that the success of an education system depends entirely on the strong leadership and synergy at all levels of the system, such as the district, provincial and national level. With this understanding, a holistic view to a provincial or district educational leadership is thus best explained and understood through a systemic inquiry into leadership - an inquiry underpinned by systems thinking theory. Senge (2006:7) developed systems thinking as a framework that makes "full patterns [of a system] clearer." In this sense, systems thinking is based on

Aristotle's famous citing of a whole that is somehow greater than the sum of its parts, which would suggest an interconnected approach to leadership within the entire educational system. Shaked and Schechter (2017:699-700) define systems thinking as an "approach advocating thinking about any given issue as a whole, emphasizing [sic] the interrelationships between its components rather than the components themselves." Fullan (2006) identifies the different levels of the education system that influence one another as the state or national policy, the district as well as the school and its community. He argues that in order for the education system to change, it was important for change to occur simultaneously at all three levels of the system (Fullan, 2009). It is within these different levels that "system thinkers" (Fullan, 2006:114) are located and regardless of their own level in the system, they connect and work with one another with full awareness of how the different levels influence one another. It is here that the role of Circuit Managers is significant, as they have the potential to strengthen the interconnections and accelerate system-wide change within the school district. If the Circuit Manager does not make these connections, the system is not likely to change or succeed. Banathy and Jenlink (2004:47-48) further supported this view by stating that a systems framework facilitates the exploration of the system and "its components and parts," enabling us to understand the embedded and interconnected nature of educational systems. They argue that it is only once we "individually and collectively develop a systems view of education that we can engage in the design of systems that will nurture learning and enable the full development of human potential." Arguably, this interconnectivity will ensure sustainability of school improvement initiatives, which Fullan (2006) argues can [only] be achieved through a systems thinking approach to change and reform.

According to Foley and Sigler (2009), creating whole systems of successful schools requires school districts to be a key player in reform and within the education system. Wahlstrom, Louis, Leithwood and Anderson's (2010) view is that the significant effects on student learning depend on creating synergy across a range of human and institutional resources, so that the overall impact adds up to something worthwhile. Wahlstrom et al. (2010) posit that among the many people who work hard to improve student learning, [district] leaders are uniquely well positioned to ensure these synergistic effects. Furthermore, research advocating the significance of district level leadership suggests that it matters and adds value to an education system (Spillane, 1996; Waters & Marzano, 2006). In this sense, effective district leadership determines the success of its schools, eventually having an impact on learner achieve-ment (Louis, Dretzke & Wahlstrom, 2010). In fact, school districts (and their leaders) are appropriately located for any system-wide change venture as they have jurisdiction over all schools within their ambit (Naicker & Mestry, 2015). Thus, effective, cohesive and coherent leadership within an educational system plays a crucial role in supporting and sustaining successful schooling. Nevertheless, we need not ignore the basic bureaucratic and hierarchical principles, as CMs are placed in positions but may have no way to influence others for whom they are responsible and make the system function.

Research Methodology

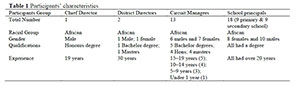

The reported qualitative study was undertaken in eight districts in the EC Province. Within the eight districts, the primary participants was a Chief Director, District Directors, Circuit Managers (CMs), and school principals. Table 1 below summarises the characteristics of the participants.

All in all, 34 participants were involved in the study. The data was collected through semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews with Circuit Managers due to availability issues. In each district, a focus group interview was conducted with two CMs (in one district, only one CM was interviewed) and we made sure that each participant answered the questions posed. Each focus group lasted between 2-3 hours in one sitting, while the individual interviews lasted mostly over one hour. All interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants.

Data Coding and Analysis

The interviews were later transcribed using an edited transcription process in order to ensure the originality and authenticity of the information. The data coding and analysis followed an iterative process as suggested by Miles and Huberman (1984:9). The transcripts were read several times while noting reflections or other remarks in the margins; sorting and sifting through the materials to identify similar phrases, relationships between variables, patterns, and theme. Throughout the process of analysis, the research questions were used to inform the emerging issues from the data.

Ethical Issues

Permission to undertake this research was obtained from the Eastern Cape Province Department of Education. We ensured that the ethical responsibilities associated with dignity, rights, safety and well-being of the participants were considered. Issues concerning voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, anonymity, were discussed in detail with the participants before participation so as to allow them the opportunity to grant informed consent.

Findings and Discussion

In this section, we present findings on the two research questions (as stated above) using themes that emerged as subheading. These findings put a spotlight on the issues raised about CMs and their offices being the weakest link in the education leadership chain.

Roles and Responsibilities of Circuit Managers When asked about their roles and responsibilities in their respective circuits and districts, Circuit Managers were all very clear about what was expected of them:

I think the very first one is the provision of tuition in schools, which means that we give support to principals in the area of curriculum management, supervision and monitor if the policies of the department are correctly implemented. One of the roles of the CM is to look at the functionality of the schools, first of all we check at the resourcing of the schools in terms of LTSM (Learner, teacher support materials). We look at the functionality of the SGB's (School Governing Bodies) ...

The core function is to support schools in the curriculum management and delivery, financial management, support staff.

The CMs recounted their roles and responsibilities as spelled out in the Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa (2013:25-26) policy on roles and responsibilities of districts, specifically focusing on the sections that deal with CMs and circuit offices. However, despite the CMs eloquence in describing their roles and responsibilities, there was consensus among interviewed education officials (including CMs and school principals), that the CMs and their circuit offices were the weakest link in the education district leadership chain. In explaining this perception, the Chief Director said:

... the circuit management is actually the weakest link. We can only effectively support schools through circuit management but it is our weakest link. Weakest in the sense then, that, I don't think we have clearly defined what a circuit management role is, so that is the first problem ... we have not been able to resource it properly, I mean the circuit manager functions to say these are the programmes that they have to carry [. ] and then also what made it even worst was we also did not actually pay attention to their reports ...

We found the above statement surprising after the CMs had explained their understanding of their management role. Confirming the claim that the Circuit Managers were the weakest link, many school principals were of the view that leadership at the circuit level was poor and questioned whether some of the CMs were even aware of their (principals' ) expected roles and responsibilities. Explaining, a principal said:

... I wish we had people who are on point, people who knows what is supposed to be done, and they are consistent. And, if you could have everyone, just everyone, this is a chain, isn't it? So everyone doing what is expected from their position. You find that sometimes there are people that I don't know if what is really their role, the Circuit Managers ...

This extract further confirms that despite the above claims, insights from the other education officials cast a doubt on the performance of their roles and responsibilities. There are two possible explanations for this discrepancy: it could mean that the roles and responsibilities of the CMs are clear on policy at national level, but not on practice at the provincial level. We also wondered whether this could mean that awareness of their roles and responsibilities as CMs contrasts with their ability to perform the said roles and responsibilities associated with the position. Nevertheless, while exploring the notion that the CMs were considered the weakest link, the CMs concurred, but identified a myriad of challenges that were affecting their performance with regards to the prescribed roles and responsibilities. The identified challenges are classified broadly as systemic, including structural, infrastructure and human resources, as well as external driven challenges such as political interference.

Systemic Factors or Challenges The structure of the Circuit offices was perceived, not only by the CMs, but by the District Directors, Chief Director and school principals, as being very problematic. Currently in the EC Province, the CMs, also known as Education Development

Officers (EDOs), have virtual circuit offices. Most of the CMs expressed their unhappiness at being called 'circuit managers,' as they felt the name was not befitting of their actual role. A bone of contention was that they were not treated like real CMs. In order to explain this view, one CM said:

... in fact, we do not even like that name, Circuit Manager, because that name Circuit Manager has a connotation that is not happening here in the Eastern Cape Province, which was supposed to happen. When you look at the other provinces like KwaZulu-Natal, like eh Western Cape and other, the Circuit Manager, the way their portfolio is made is way different from us. For if you can ask me to go show you my office at Circuit level, I will tell you that I don't have it.

Apparently, the name "Circuit Manager" implies that one has a fully functioning circuit office located in their area of jurisdiction. However, all the CMs were located at their district offices, despite having demarcated circuits. Providing clarification, one CM noted:

... first of all, I am not supposed to be here at the district office, I am supposed to be in the circuit where I am allocated to. According to the organogram, I am supposed to have a fully-fledged Circuit Office ...

Some districts and circuits were said to be located in other cities, far away from the very district and circuits they were supposed to serve. This arrangement posed a huge challenge regarding the distances to be travelled in order for the CM to visit the schools, which meant that some schools were hardly or never visited. The CMs were very clear about the need to have their own Circuit Offices that would be located within the vicinity of their schools and that they should not be sharing offices at the district level, as was the case in many districts:

... I need a circuit which is full of manpower, which has got machines, I mean secretary, machines [. ] I am supposed to have someone responsible for human resources, supply chain management. Now I don't have, nothing, nothing.

Further aggravating the complex situation, as noted in the above excerpt, was the shortage of infrastructure, material and human resources, necessary for CMs to be able to perform their roles. All the interviewed CMs lacked the basic tools of trade (cars, printers to print materials for schools etc.), which were needed in order to visit the schools and in order to ensure that CMs successfully perform their duties. Also, in all the districts visited, the CMs did not have their own Subject Advisors or secretaries who would be able to assist in their absence when they are visiting schools. This practice contravenes the DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013:29) policy proclamation that "in view of the vital importance of the early years of schooling, circuit offices need their own specialist Subject Advisors to support teachers in the primary school phases." The lack of Subject Advisors for each circuit office points to a slow or lack of policy implementation in these circuits and districts.

The analysis of data also shows that most of the CMs managed high numbers of schools in their circuits, something that was contrary to the DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013:16) policy. The policy declares that the appropriate size of an education circuit is best expressed in terms of the number of schools for which a circuit has responsibility. Accordingly:

... an education circuit offices must be responsible for no less than 15 and no more than 30 schools, and the average number of schools per district must not exceed 25 . (DBE, Republic of South Africa, 2013:16).

The policy further states that "a district must comprise no less than five and no more than 10 circuits'" Yet this was not happening, as most of the districts had more than 15 circuits. Most of these circuits had more than 50 schools, and districts totalling more than 250 schools. What is clear from the officials' insights was the difficulty of adhering to the policy and precise implementation of it as the contextual factors (workforce shortages), which did not allow for stringent application of the such.

The rate of vacancies for the CM positions in the selected districts was also considered high, resulting in some Circuits operating without CMs. Consequently, the few existing CMs were being asked to manage two or three circuits, each with more than 50 schools. This was despite the fact that these CMs were already over stretched due to a high number of schools in their own circuits. Expressing the plight of shortages when it comes to CMs, one CM noted that:

... this district is very broad, it a mega district. It is a combination of three districts [. ] which gives us 15 circuits. We are running short of six Circuit Managers, I mean there are six circuits without managers. That is what is hitting us hard ...

From the above quote, it can be seen that the CMs district had become large, because three districts had been merged, but without increasing the infrastructure, material, and human resources. The DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013) policy mandates that District Directors ensure that a CM receives adequate support and resources in order to fulfil the functions entrusted to the circuit office. However, the District Director did not have powers to employ CMs, as that was the function of the Provincial Department of Education. This practice also shows a lack of alignment between the policy, highlighting some contextual challenges within the province.

Also corroborating the claim that CMs were compromised in the education management chain, a newly appointed principal complained about the lack of orientation and induction, which was supposed to be conducted by his/her respective CM but unfortunately did not occur in time due to shortage of CMs in some circuits. Furthermore, principals who did indeed have CMs were also not happy, citing lack of full support from their CMs:

...for instance, if you have a problem with a machine and we cannot make photo copies and the exams are ongoing, 'I believe that my circuit manager should assist in anyway, but they don't know how to assist us even in the day-to-day running of the schools [...] with my circuit manager I don't know what to report or not to report to her...

From these insights, it seems that the identified issues and challenges, weakened and compromised the role that should be played by the CMs and their circuit offices. A caution noted by Bottoms and Schmidt-Davis (2010) states that a district cannot hold school principals accountable when it does not have high-quality staff to support the schools or when the role of district staff is so poorly and narrowly defined that it is not held accountable for providing the support services schools need.

External Challenges

Most of the Circuit Managers viewed their position as being undermined, an observation also confirmed by the District Directors and the Chief Director. Contributing to their state of affairs was their inability to resolve some of the challenges that confronted their schools, due to the interference from some teacher unions in their decision-making.

You know I am a circuit manager, but you find that I am toothless. You know, you find that there are many cases where teachers have done wrong, gross incidence which really need to, but then it's this whole process of negotiations; there is union, there is that, there is labour, I don't know; but when you find on other provinces I think there is a clear line between managers of education and the labour unions. I think this affects us. (Circuit Manager)

While the role of teacher unions interfered in the running of education at the local level in some districts in the province, in other districts, teacher unions facilitated unfair practices. Adding to the challenges was the questionable appointments of some of the CMs, facilitated by the unions, even though they did not merit the positions. Expressing concern over such tendencies and the reasons why CMs are considered to be the weakest link in the education chain, the Chief Director noted that:

... I think the other disservice we did with the circuit managers was, it is a sort of provincial political issue, we did not necessarily appoint the people who merit the position. As a result, then because the person is a member of a [...] (naming the teacher union), that kind of thing, then we would appoint that person to a Circuit Manager. And in many cases actually, teachers or mediocre principals would then leapfrog performing principals and become circuit managers.

In the Chief Director's observation, the process of appointing CMs was somehow unfair, as deserving individuals were sometimes left behind. This view was strongly corroborated by school principals who cited examples of other principals who collapsed their schools but were later appointed to serve as CMs. This habit was contrary to what the literature suggests regarding district officials, that school districts need personnel with skills required in order to step right into positions as effective leaders, who require minimal on-the-job learning (Dodson, 2015). The issue of CM appointments was described as very complex and political in nature, as these appointments were made based on political alliances and "cadre deployment," something which has been noted as very common in the provincial structures. The challenge that accompanied these questionable appointments was that such appointees become handicapped as they will always be reminded about the deployment in the position. Expressing frustration, the Chief Director argued that the effects of appointing someone who do not merit the position is that the CM then struggles to perform his/her duties of mentoring principals, who are aware of his/her incompetency. In this case, the CM is already compromised, and will struggle to achieve anything within those schools.

(Referring to Circuit Managers) ... in some cases they themselves would be afraid to go back to those schools because you are supposed to be the mentors of the principals, but when you get there, you cannot mentor that principal because you are junior and the principals is senior to you

Consequently, many CMs were not respected by school principals, who resent being beholden to such an "incompetent" individual. Explaining this challenge, one principal had this to say:

...Like I said, I don't know what they are doing, because somebody said they are the principals of the principals, fine, if somebody is my principal I expect the person, first of all you cannot supervise what you do not know. What I observed and realised from most of them (referring to circuit managers), they were never school principals. Maybe that is not the issue, however, the day-today running of things they don't understand it ...

From the above insight, it is apparent that the principal questions the CM's knowledge and experience in the administration of schools, casting doubts that perhaps, since some of them had never been principals prior to assuming the role of CMs, that this could be the reason for their knowledge gap, even regarding basic issues. Also showing discontent, another principal said:

... Circuit managers are the weakest link, they cannot even take decisions. They are just there to divulge information. They even fail in that function of disseminating information, because you will find that these circulars, we always get circulars very late whereas there is a circuit manager who should be a go between schools and the district, but they do not fulfil their role. They are the weakest link, even if they are not there, it cannot cause any harm to the system.

Another principal had this to say:

... For instance, if we are going to talk about SGBs (School Governing Bodies), you tell them (referring to CM) that there is a problem with SGB like this and that, they will not know what the SGB was supposed to do. You tell them that you have a problem with an unsigned cheque, they wouldn't know how many secretaries are supposed to be involved .

Clearly, these principals perceived some of the district officials as clueless, and even lacking awareness regarding their (principal) roles and responsibilities as well as the SGB's functions. This is worrying, because the DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013:25) policy states that, "principals depend on the circuit office for information, administrative services and professional support. " These findings are stark, and suggest a system that is not in synch with itself. Fullan (2006) argues that leadership at all levels of a system must feed on each other to ensure sustainability. Bantwini and Feza (2017) suggest a need for vision, focus and dedicated leadership in the districts that will ensure that educational policies are fully implemented in order to yield the desired outcomes. We reiterate this assertion and argue that the failure of the circuit manager as the middleman has the potential to weaken the whole system.

Implications for District Education Leadership Previous research suggests that the issues surrounding the capability and reality of district officials are some of the factors that are likely to determine the success or failure of reforms (Bantwini & Diko, 2011). Systems thinking theory suggests an interconnected approach to leadership within the entire educational system in order to facilitate change within broader reforms (Fullan, 2005; Senge, 2006). The findings in this study indicate that despite their self-proclaimed clarity on their roles and responsibilities, the CM's practice left much to be desired, portraying them as the weakest link in the district leadership chain. Insights from the various interviewed officials further cast a doubt on the CM's leadership competency, full comprehension of their duties, and how to successfully support their principals and schools. Complicating the state of affairs further was the myriad other factors that suggest a disconnected view of Circuit Managers' roles from other leaders within the districts. It is this disconnected view of leadership within the system that results in the roleplayers laying the blame at the feet of the circuit managers, labelling them as the weakest link. We argue that an interconnected view of the district officials' roles would recognise their interdependency (Fullan, 2005; Senge, 2006) and eliminate the view of Circuit Managers as the weakest link. As Senge (2006:67) observes, "systems thinking shows us that there is no separate other; that you and the someone else are part of a single system. The cure lies in your relationship with your enemy."

Further evident from the study's findings is that the current structure of the circuits creates challenges that are detrimental to the functioning of the CMs. CMs perceive the lack of a proper physical structure of the circuit offices, located among the schools they service, contrary to the title "circuit office" and contrary to the DBE's, Republic of South Africa (2013:25) policy assertion that "the circuit office is a field office of the district office headed by the Circuit Manager." These findings demonstrate the gap between policy and practice in the province, which may be due to existing ground-level challenges. Coupled with this is the issue of large districts with too many schools, that complicates the structuring and resourcing of circuits, and therefore has dire implications for the effective functioning of the Provincial Department of Education as a whole. The idea of relocating the CMs and their offices closer to their schools seems popular among all the officials, and is deemed a viable option that would increase the effectiveness of not only the CMs and their offices, but the entire district and provincial system. Drawing support from Fullan's (2005) assertion that system thinkers build collaborative relationships and structures for change, and from Moorosi and Bantwini's (2016) and Naicker and Mestry's (2016) argument for a collaborative approach within districts, we argue for a strategic provincial planning that is informed by a systems perspective to change. This, we believe would harness and distribute effectively, the limited resources within the province, while it ensures collective responsibility and accountability of successes and failures.

We find it ironic that the CMs are expected to support principals and their schools, but are deprived of the basic resources needed to carry out their mandate. Therefore, we ask: how then can the system sincerely hold them and their circuit offices accountable when knowing that they are operating under severe resource constraints? If we desire schools that improve and CMs that succeed in their efforts, the CMs and their offices need to be adequately provisioned with relevant resources. The lack of provisioning of basic resources and infrastructure is a potentially crippling factor in education and has been a persistent problem in the province (Bantwini & Diko, 2011). There is a need to create a systemic cultural shift across the provisioning of resources necessary to undertake expected duties and necessary to ensure sustainable change. The OECD (2012) observes that the lack of systemic support and flexibility and limited or ineffective use of resources, including staff, make meeting the challenges posed by low performing disadvantaged schools difficult to meet. Wahlstrom et al. (2010) contends that leaders who strike a proper balance between stability and change emphasise two priorities in the direction they provide and the influence they exercise: they work to develop and support people to do their best, and they work to redesign their organisations to improve effectiveness. Thus it is imperative that support is not offered through highly politicised, trumpeted schemes, but rather via practical, systemic and ongoing means. For this to happen, district officials would need to play a more agentic leadership role within system-wide change and move away from compliance and control.

We recognise that agency would be meaningful where there is capacity to perform roles. The high rate of CM vacancies has the potential to contribute to low morale among the few existing CMs in the districts, as they have to carry more of the workload. We argue that the filling of vacancies cannot be left to chance or depend on individuals who will apply when the positions are advertised. Districts need to develop systemic strategies for both the demand and supply issues, in order to ensure timely filling of vacant positions accompanied by the necessary capacity building measures. This calls for a district-wide leadership development plan that will ensure "collective capacity building" (Naicker & Mestry, 2015:8). Foley and Sigler (2009) state that smart districts develop and provide leadership necessary for the district and its schools to accomplish the goal of providing all students with an effective education. Corresponding to the above issue, we believe that the success of the school partly depends on the extent to which districts, through their circuits, are able to provide support and implement the necessary changes and improvements. Also, it depends on the quality of the leadership and management provided and the professionalism of the leaders within the system. Fullan (2005) argues that it is the "discontinuity of direction" that results in high turnover rates and that this can be avoided by system-wide capacity building that ensures a sustainable pool of 'pipeline' people, who are ready to take over new leadership positions as they become vacant.

The challenge of officials who are appointed in positions that they do not merit cannot be ignored, or be left to somehow resolve itself. We argue that the system needs to discourage it and ensure that correct appointing procedures or policy stipulations are adhered to. Also imperative from the finding is the need for continuous monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation and prescribed procedures at the ground level by various delegated officials. However, one of the strategies to assists CMs who are already compromised due to an unwarranted appointment is to provide targeted professional development. Purposeful developed leadership programmes targeting leadership knowledge, skills and dispositions will be of value for these individuals.

The interference of teacher unions can clearly disempower the CMs and the work that they do.

This can have detrimental effects in the performance of the CM, eventually affecting their districts' functioning. Hence, we are of the view that the national Department of Basic Education and the leadership of teacher unions have a critical role to play as "system thinkers" (Fullan, 2005, 2006) who are part of the solution across the different levels of the education system. Fullan (2005:40) argues that the more the leaders become system thinkers, the more they "will gravitate towards strategies that alter people's system-related experiences" that will ultimately be part of the solution towards changing of the system itself. Indisputably, the role played by the teacher unions as workers' representatives is critical in a democracy, however, in many districts and circuits it seems like the unions have been hijacked by members who have a different agenda. Working closely and productively with the unions would contribute towards a holistic view of the bigger picture (Naicker & Mestry, 2016; Shaked & Schechter, 2017), rather than focusing on some of the system's parts. Senge (2006:7) argues that "for as long as we focus on snapshots and isolated parts of the system, we will never get to solve our problems," while Naicker and Mestry (2016:10) asserts that if the "interrelationships between the elements of a system are weak, it is unlikely that a system will succeed." We draw on these assertions to argue for that it is perhaps a system thinking approach that is more likely to facilitate change that will provide more sustainable improvement of the education system.

The problems associated with education in the Eastern Cape are complex and have been ongoing for some time. We view these findings to be also relevant to the global community as they reveal how poor resources can negatively impact on effective delivery of quality education in the emerging economies. However, we believe that if leaders (circuit managers, principals etc.) are trained as systems thinkers who deeply understand the systemic approach to educational change, they will work collaboratively towards the attainment of educational goals.

Conclusion

The challenges confronting the CMs and their circuits have a direct influence on performing their expected roles and responsibilities, which also impact negatively on their schools and the entire system. The CM's and their offices are positioned (supposedly) to provide a climate of high expectations, a clear vision for their schools, and the means to realise that vision. They are supposed to bring inspiration and hope to their schools, ensuring that they all succeed irrespective of their different plights. However, in the reported study the CM's position are compromised as they are not treated in accordance to their 'title,' as well as CM's in other provinces. Undoubtedly, CM's and their offices are a necessity and the success of many rural schools depends on their full support. Efforts to improve the performance of schools in the circuits under discussion will not succeed until they are strengthened. The expectation for CM's to effectively deliver and succeed on their roles and responsibilities ought to correspond with provision of the necessary resources and infrastructure. As much as they are tasked to support schools, CMs also need to be supported to enhance their capability and leadership skills. Boundaries needs to be set so that educational leaders within the system can be able to conduct their work without unnecessary interference.

Notes

i . According to DBE, Republic of South Africa (2013), an education district is the first-level administrative subdivision of PDE and the district office headed by District Director is responsible for the Basic Education institutions in its district.

ii . Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Banathy BH & Jenlink PM 2004. Systems inquiry and its application in education. In DH Jonassen (ed). Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Bantwini BD & Diko N 2011. Factors affecting South African district officials' capacity to provide effective teacher support. Creative Education, 2(3):226-235. Available at http://file.scirp.org/pdf/CE20110300002_89841903.pdf. Accessed 4 July 2018. [ Links ]

Bantwini BD & Feza NN 2017. Left behind in a democratic society: A case of some farm school primary schoolteachers of natural science in South Africa. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(3):312-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1124927 [ Links ]

Bottoms G & Schmidt-Davis J 2010. The three essentials: Improving schools requires district vision, district and state support, and principal leadership. Atlanta, GA: Southern Regional Education Board. Available at https://www.sreb.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/10v16_three_essentials.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2013. [ Links ]

Christie P, Sullivan P, Duku N & Gallie M 2010. Researching the need: School leadership and quality of education in South Africa (Report prepared for Bridge, South Africa and Ark, UK). Available at http://www.bridge.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BRIDGE-in-partnership-with-ARK-School-Leadership-Report.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2018. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education, Republic of South Africa 2013. Policy on the organization, roles and responsibilities of education districts. Presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Basic Education. [ Links ]

Dodson RL 2015. What makes them the best? An analysis of the relationship between state education quality and principal preparation practices. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 10(7):1 -21. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1138292.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2018. [ Links ]

Foley E & Sigler D 2009. Getting smarter: A framework for districts. Voices in Urban Education, 22:5-12. Available at http://vue.annenberginstitute.org/sites/default/files/issues/VUE22.pdf#page=7. Accessed 1 July 2018. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2005. Leadership and sustainability: System thinkers in action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2006. The future of educational change: System thinkers in action. Journal of Educational Change, 7(3):113-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-9003-9 [ Links ]

Fullan M 2009. Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Education Change, 10(2-3):101-113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z [ Links ]

Louis KS, Dretzke B & Wahlstrom K 2010. How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a national US survey. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(3):315-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.486586 [ Links ]

Marzano RJ & Waters T 2009. District leadership that works: Striking the right balance. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. [ Links ]

Miles MB & Huberman AM 1984. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Moorosi P & Bantwini BD 2016. School district leadership styles and school improvement: Evidence from selected school principals in the Eastern Cape Province [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 36(4):Art. # 1341, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n4a1341 [ Links ]

Naicker SR & Mestry R 2015. Developing educational leaders: A partnership between two universities to bring about system-wide change. South African Journal of Education, 35(2):Art. # 1085, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n2a1085 [ Links ]

Naicker SR & Mestry R 2016. Leadership development: A lever for system-wide educational change [Special issue]. South African Journal of Education, 36(4):Art. # 1336, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n4a1336 [ Links ]

OECD 2012. Equity and quality in education: Supporting disadvantaged students and schools. Paris, France: Author. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en [ Links ]

Senge PM 2006. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Shaked H & Schechter C 2017. Systems thinking among school middle leaders. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 45(4):699-718. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1741143215617949 [ Links ]

Spillane JP 1996. School districts matter: Local educational authorities and state instructional policy. Educational Policy, 10(1):63-87. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0895904896010001004 [ Links ]

Wahlstrom KL, Louis KS, Leithwood K & Anderson SE 2010. Investigating the links to improved student learning: Executive summary of research findings. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. Available at http ://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning-Executive-Summary.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2018. [ Links ]

Waters JT & Marzano RJ 2006. School district leadership that works: The effect of superintendent leadership on student achievement (Working paper). Denver, CO: Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning (McREL). Available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED494270.pdf. Accessed 24 November 2016. [ Links ]