Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.37 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n3a1391

Promoting resilience among Sesotho-speaking adolescent girls: Lessons for South African teachers

Tamlynn C JefferisI; Linda C TheronII

IOptentia Research Focus Area, School of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa. tjefferis10@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Teachers are a crucial part of young people's social ecologies. Considering that black South African adolescent girls remain the most marginalised group in South Africa, the purpose of this qualitative, phenomenological study has been to explore if and how teachers champion resilience among black adolescent girls living in rural contexts of structural adversity. Using Draw-and-Talk and Draw-and-Write methods, 28 Sesotho-speaking adolescent girls from the Free State Province of South Africa generated a total of 68 drawings. The drawings were analysed using inductive content analysis. The findings include teachers actively listen and provide guidance; teachers motivate girls towards positive futures; and teachers initiate teacher-girl partnerships. These findings prompt three strategies to support teachers' championship of resilience, namely pre-empt support; advocate for a changed education landscape; and communicate constructive messages.

Keywords: adolescent girls; resilience; rural; Sesotho-speaking; social ecology; structural adversity; teacher(s)

Introduction

Resilience, or positive adaptation to adversity, is currently widely understood as a process rather than an individual trait (Masten, 2014). According to the Social Ecology of Resilience Theory (SERT), which is the theoretical framework of this article, adjusting well to adversity (i.e. resilience) is a reciprocal process between individuals and their social ecologies (Ungar, 2011). Both the individual and the social ecology play active roles in facilitating positive outcomes. Individuals navigate towards and negotiate for culturally meaningful resources; the social ecology provides resources that support positive adjustment (Ungar, 2008, 2011, 2012). Although resilience demands input from both the individual and social ecology, there is growing emphasis on the influential contributions that a social ecology makes to the resilience of young people (Panter-Brick, 2015).

Globally, schools are a vital part of most young people's social ecologies (Masten, 2014). Many young people spend the majority of their daily lives at school (Theron, 2016a). For example, in South Africa, school-going young people spend a significant amount of time (around seven hours per day) in formal school classes (excluding extracurricular activities), and a total of 197 days of the year at school (School Terms South Africa, 2016). School engagement and regular school attendance have been widely associated with resilience. This association can be understood in the context of schools facilitating adaptive processes, and constituting a secure space for young people in the midst of trauma, structural disadvantage, or other significant adversity (Doll, Jones, Osborn, Dooley & Tuner, 2011; Holt, 2016). Teachers in particular have the potential to be instrumental in protecting young people who face daily difficulties or emergency situations. In fact, Ungar, Russel and Connelly (2014) report teachers to be the most critical school-based influence on the resilience of young people.

Teachers who champion youth resilience make themselves accessible to young people; actively listen and engage with students; are empathetic to the difficulties learners face; take responsibility for educational outcomes; advocate for the support of learners considered at risk; address bullying; and promote pro-social bonding (Theron, 2016a; Ungar et al., 2014). In other words, resilience-enabling teachers provide psychosocial support to vulnerable children (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011). Psychosocial support addresses the psychological and social challenges that threaten people's wellbeing (World Health Organisation, 2015). For example, psychosocial support might involve assisting individuals and their families to cope well with HIV-related difficulties.

According to prevailing South African education policy outlined in the Norms and Standards for South African Educators (Department of Education (hereafter DoE), 2000) teachers are expected to go beyond their educational role and take on a pastoral role which includes providing psychosocial support (Schoeman, 2015). Although some South African teachers have mastered this expectation (e.g. Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Phasha, 2010), pre-service and in-service teacher education programs generally do not prepare teachers for a pastoral role. Accordingly, there is a need to capacitate teachers to optimally fulfil necessary pastoral duties.

One way of capacitating teachers to fulfil this role is to identify research-based lessons relating to how best to promote resilience. In short, this article aims to do just that. To distil research-based lessons that can support teachers to champion resilience, this article draws on visual and narrative data generated by Sesotho-speaking adolescent girls from rural parts of the Thabo Mofutsanyana District, who participated in the Pathways toResilience Study (P2R) South Africa (see http://www.resilienceresearch.org/). The question which informed the original P2R research was: why are Sesotho-speaking adolescent girls living in rural contexts of structural adversity resilient? For the purposes of this article, we only consider data segments that relate to how teachers supported resilience. Our narrower focus is the question informing this article, namely: what do adolescent girls' accounts reflect about how teachers (as key social-ecological stakeholders) facilitate resilience and what insights can be drawn on to develop strategies for teachers to champion resilience? From this teacher-focused data, we distilled strategies that could support teachers to fulfil their pastoral role. The strategies which emerged are likely applicable to teachers working with young people marginalised in other parts of the Global South, as well as those in the Global North. Even though the strategies flow from a study with adolescent girls, they are broad, and therefore probably beneficial for male students too.

Review of the South African Literature: Teachers and Resilience

There is an abundance of literature which dem-onstrates that many South African teachers champion resilience. As detailed below, this lit-erature characterises resilience-fostering teachers as actively caring and/or motivational (Ebersöhn, 2007; Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Heath, Donald, Theron & Lyon, 2014; Johnson & Lazarus, 2008; Malindi, 2014; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Mampane & Bouwer, 2006; Mosavel, Ahmend, Ports & Simon, 2015; Phasha, 2010; Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012; Theron, Liebenberg, & Malindi, 2014; Theron & Phasha, 2015; Theron & Theron, 2010, 2014; Van Rensburg, Theron, Rothmann & Kitching, 2013). However, not all teachers do facilitate resilience. Some teachers have been reported to heighten vulnerability in young people (for examples see Kruger & Prinsloo, 2008; Phasha, 2010). It cannot be assumed, therefore, that all teachers are capacitated to champion resilience among young people. This emphasises the need to support teachers to facilitate resilience, particularly in more challenging contexts such as rural districts that are structurally disadvantaged.

Actively caring teachers

Teachers demonstrated empathy through immediate emotional and/or practical responses that assisted learners to cope well in spite of hardships such as sexual abuse, poverty, loss, or streetism. They showed emotional care by listening to the diff-iculties of young people, encouraging learners, and treating learners fairly and respectfully (Dass-Brailsford, 2005; Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Heath et al., 2014; Johnson & Lazarus, 2008; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Phasha, 2010; Theron et al., 2014; Theron & Theron, 2010, 2014). For instance, Malindi and Machenjedze (2012) reported how supportive teachers who created safe spaces for children to discuss difficulties with them had helped to ease feelings of loneliness among male street children in the Free State. In another in-stance, Johnson and Lazarus (2008) explained that in spite of reports of Western Cape adolescent learners not trusting some teachers or not feeling connected to school, teachers who listened to and laughed with learners nurtured learner resilience. Moreover, caring actions involved teachers at times reaching out to learners they perceived as vul-nerable, rather than only reciprocating support when approached by young people (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012; Theron & Theron, 2014). Caring teachers ulti-mately formed partnerships with youth by actively providing psychosocial support (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Theron & Theron, 2014).

Pragmatic caring involved teachers finding ways to provide learners with food to ease their hunger or teachers referring learners to community services such as health and welfare services (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Malindi & Mach-enjedze, 2012; Phasha, 2010; Theron & Engel-brecht, 2012; Theron et al., 2014). For example, Malindi and Machenjedze (2012) reported that a teacher supported a male street child by giving a sandwich to him when he disclosed to her that he had no food. Additionally, the teacher referred him to a clinic where he could receive medication, as he had fallen ill at school. This supported him to remain engaged in school while living on the street. In another example, Ferreira and Ebersöhn (2011) found that teachers had taken the initiative to develop lists of important community services (i.e. family welfare organisations, health services) to which they would refer young people in need of auxiliary means of coping. Similarly, Theron et al. (2014) reported that teachers facilitated welfare services or police protection services in order to support youth who were orphaned or who experienced abuse/neglect.

Motivational teachers

Teachers inspired young people by being positive role models of beating the odds, and by urging young people to invest in their education as a means towards upward life trajectories (Dass-Brailsford, 2005; Ebersöhn, 2008; Malindi, 2014; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Mosavel et al., 2015; Phasha, 2010; Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012; Theron et al., 2014; Theron & Theron, 2014). For example, first-year university students from dis-advantaged backgrounds recounted that teachers who experienced similar childhood circumstances to them, but still gained professional qualifications, were seen as real life examples of overcoming adversity (Dass-Brailsford, 2005). These teachers also took on mentorship roles to inspire the youth to do the same. To this end, they actively en-couraged young people to be future oriented by investing in education. Similarly, Theron et al. (2014) reported that teachers who encouraged school-going young people in the Free State to prioritize education facilitated future directedness in them, which helped them to persevere in the face of difficulty. Likewise, Ebersöhn's (2007) par-ticipatory study with at-risk adolescents from Limpopo provided evidence that teachers who encourage future directedness were a source of strength for young people exposed to crime in their community.

Research Methodology

Our purpose in this article is to distill evidence-based strategies that might support teachers to fulfil their pastoral role in a resilience-enabling way. To achieve this purpose we prioritised girls' accounts of how their teachers had contributed to their resilience. The generation of these accounts took place during the P2R study and followed a phenomenological design (as explained by Cres-well, 2014). We re-analysed these accounts to answer the question: "what do adolescent girls' accounts reflect about how teachers (as key social-ecological stakeholders) facilitate resilience and how can these insights be drawn on to support teachers to champion resilience?" In doing so we adopted a social constructivist approach as we sought to make meaning of girls' interpretations of their teachers' attitudes and actions.

Participants

Twenty-eight school-going Sesotho-speaking girls living in rural Thabo Mofutsanyana, Free State Province, South Africa participated. Gatekeepers (i.e. two P2R community advisory panel members, a social worker from a local children's home, social workers from a family welfare organisation, and teacher) facilitated recruitment. They prioritised the inclusion of black adolescent girls given the worrying reality that black South African girls and women remain the most marginalised and at-risk group in South Africa (De Lange, Mitchell & Bhana, 2012; Jewkes, Gibbs, Jama-Shai, Willan, Misselhorn, Mushinga, Washington, Mbatha & Skiweyiya, 2014).

The P2R was guided by an advisory panel comprising 11 local community members, who were engaged in serving/supporting/mentoring young people. This panel conceptualised a set of criteria which denoted resilience. As documented in Theron, Theron and Malindi (2013) the indicators of resilience included: access to an active support system; being value driven; educational progress; a vision for the future; tolerance; and intrapersonal strengths (e.g., assertiveness, self-worth). The gatekeepers used these criteria to pur-posefully recruit girls who demonstrated resilience, despite being challenged by various risks such as death/loss of loved ones, physical/emotional/sexual abuse, and bullying by peers.

Table 1 below summarises the girls' demo-graphics (grouped according to the place from which they were recruited). As recommended by the gatekeepers, we grouped the girls according to the organisations from which they were recruited. Because the group of girls from the family welfare organisation was large, we invited the girls to divide into groups. In total, then, four groups of girls generated data using the methods explained next.

Generation of Drawings

Within the P2R, data collection took place over a period of 18 months from March 2013 to August 2014. Following Guillemin (2004) we used both Draw-and-Talk and Draw-and-Write to facilitate generation of a set of drawings and explanations that elucidate what supports resilience among Sesotho-speaking girls. We chose these methods because they have the potential to uncover deep insights that may otherwise be hidden when using traditional research methods with participants (Mitchell, Theron, Stuart, Smith & Campbell, 2011). According to Guillemin and Drew (2010) using drawings can assist participants to fully express themselves because experiences are not always easy to verbalise, particularly in a second language.

We met with each group twice (six weeks apart). On both occasions, we asked the girls to create drawings using the following prompt "please draw how you cope well in spite of what makes your life hard and please explain your drawing to us." We provided girls with paper, pencils, and colour pencils. There was no time limit to the activity, and we reminded girls that how well they drew was inconsequential - we were interested in what they drew and their explanations of these contents. The same activity was repeated on the second occasion we met with the girls, in order to generate deeper insights into the girls' resilience processes. The adolescent girls participated in the second activity with even more enthusiasm than the first, possibly because familiarity with the in-struction and method supported a sense of confidence (see Jefferis & Theron, 2015).

The girls verbally explained their drawings to the rest of the group and researchers. This constituted an unstructured group interview, allow-ing us to probe and clarify the meanings of the girls' drawings. Examples of probes included: "could you tell us more about why that was helpful?" and "In what ways did [drawn resource] help you to do well in life?" The group interview format also created a safe, supportive atmosphere between the girls as they shared their drawings. The girls patted one another in affirmation, pro-vided positive feedback to one another, and expressed their agreement in what was important in one another's drawings.

All of the group interviews took place in English, which was not the girls' first language. Despite having translators present, the girls seemed to prefer responding in English (which was the language in which they were being schooled). The preference for English may have led to less detailed explanations on their part, where more detailed explanations might have led to richer understanding of how teachers promote girls' resilience.

Following preliminary analyses of these drawings, we met with 11 girls for a third time. This third meeting eventually took place approx-imately 15 months after the first two sessions. The delay was due to logistical challenges, including repeated unforeseen schooling and domestic arrangements that complicated the girls' partici-pation. In the end, the 11 girls were those who could attend (i.e. a convenience sample). They shared similar demographics and circumstances that were common in the larger group.

In spite of the girls including teachers in the above drawings and explanations, these seldom explained how teachers and schools champion resilience. Therefore, our aim during the follow-up session was to uncover insight into how teachers support the girls' resilience. Following Guillemin (2004), we engaged the girls in the 'Draw-and-Write' method, which involved asking the girls to create a drawing and explain their drawings in writing. The Draw-and-Write was led by the following prompt "do your teachers help you to do well in life? And if so, how do they help you to do well in life?" And please explain your drawing to us by writing a few sentences at the back of your drawing." We asked this specific question to the girls because the existing dataset included references to teachers as supportive, and we wanted to understand how teachers were supportive. Our earlier use of 'Draw-and-Talk' led us to wonder if verbal explanations (rather than written ones) communicated in a group context influenced girls' explanations of their drawings, because of simi-larities in some of their explanations. To address this, we instead chose 'Draw-and-Write', followed by verbal conversations with the girls about their drawings and written explanations, to ensure that the group process did not pre-empt any of the girls' explanations of their drawings.

Data Analysis

All of the group interviews were transcribed verbatim, and these transcripts, along with the drawings, constituted the data. Following Creswell (2014) we conducted inductive content analysis. Our analysis was guided by the research question: what do girls' accounts reflect about how teachers (as key social-ecological stakeholders) facilitate resilience? First, we open-coded (i.e. assigned a label) all segments of text in the transcripts and symbols in the drawings that included references to teachers or school. In general, these codes were a paraphrase of what was drawn/explained. For example, if a school building was drawn and labelled 'my school' we coded this as 'drawing of school building.' If the transcript explaining the significance of the school building referred to teachers offering advice, e.g. 'she advise me and I take her advice', then we coded this as 'teacher offers advice.' We then conducted axial coding, where we grouped similar codes together and labelled each group. The label summarised what was common to the grouped codes (e.g. teachers are emotionally supportive). Following this, we discussed the axial codes through consensus dis-cussions (see Saldaña, 2009) and reached agree-ment on the final themes (e.g. teachers create safe relational spaces for girls to discuss difficulties). Once we reached agreement on the final themes, we reflected on the themes and identified key ways in which teachers can promote girls' resilience.

Trustworthiness

In line with Creswell (2014), we enhanced the trustworthiness of the preliminary data analysis by conducting member-checking with 11 of the girl-participants. We reached agreement on the key findings of this study through several consensus discussions (as mentioned previously). The first author presented the findings to the AP. Their endorsement supported our confidence in the findings. To ensure dependability, we specified the recruitment criteria that guided participant selec-tion, and unpacked the design and data analysis of this study so that it can be replicated by other researchers.

Ethics

We obtained ethical approval from the research ethics committee of the institution to which we were affiliated at the time of the study (Clearance number: NWU-00006-09-A2), from the Free State Department of Education, and from each of the organisations to which the adolescent girls were affiliated. Prior to gaining consent from the ado-lescent girls and their parents, we thoroughly briefed the gatekeepers on the aim, risks, benefits, and procedures of the research process. The gatekeepers then identified potential participants and explained the study to the adolescent girls they identified. Following this, they distributed the consent documents to the adolescent girls, who obtained signed consent to participate from their parents. The consent forms provided a detailed explanation of the aim of the study, all of the procedures, as well as the risks and benefits for the girls in simply written informative consent doc-uments. The adolescent girls' parents/guardians consented to their participation. Before we began the visual research process, we re-explained the aims, procedures (making drawings and explaining them), risks and benefits to ensure the girls understood what the research would entail, and to gain their full assent. We asked the adolescent girls for permission to keep and use their drawings or to photograph their drawings should they wish to keep them (none utilised the latter option). We explained that their drawings might be used in conference presentations, research publications, or class presentations.

Findings

This study aimed to answer two research questions: (1) what do adolescent girls' accounts reflect about how teachers (as key social-ecological stake-holders) facilitate resilience?; and (2) what insights can be drawn on to develop strategies for teachers to champion resilience? Our findings confirmed that rural teachers do, on occasion, support girls' resilience. Although mothers, sisters and friends (girls) were most likely to facilitate resilience, there was fairly regular reference (i.e., 12 out of 28 participants or 43%) to teachers. Teacher facili-tation of resilience revolved around three key themes: (i) teachers actively listen and provide guidance; (ii) teachers motivate girls towards positive futures; and (iii) teachers initiate teacher-girl partnerships.

Teachers Listen and Provide Guidance

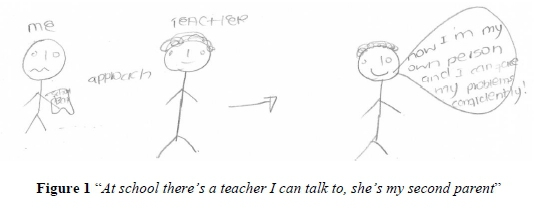

Supportive teachers were those who the girls felt cared for them. Caring was demonstrated when teachers listened to their difficulties, and provided constructive advice as to how to deal with whatever was challenging them (e.g. loss or peer pressure). The girls felt that this advice buoyed them because it facilitated successful management of what was troubling them. This is illustrated in the excerpts below, as well as Figure 1:

"For me to be strong, as I said regarding [female teacher] she advise me and I take her advice ... when something … make me sad I go … to [female teacher] or [another female teacher] and talk to them, and then they'll advise me and that make me to be strong" [Participant 3, Draw-and-Talk].

"Well, the reason why we included a teacher is because in our schools, our teachers are very supportive, most especially to children who are disadvantaged, and who [have] a problem with their self-esteem … For instance, in my school [...] most of the teachers there are very supportive … they will [talk] with you though the journey and guide you so that at the end you can make the right decision" [Participant 2, Draw-and-Write].

In another example, Participant 11 explained that she felt the advice from her teacher assisted her to cope well:

"Teachers are quite supportive to us, because at my school sometimes I talk to a certain teacher. She helps me a lot, because she gives me advice about life. When I sit alone and digest what she said, I think and see that she's right."

In their responses, the girls compared these caring teachers to parent figures. For instance, Participant 3 labelled the teacher she drew "a second parent" (see Figure 1: "At school there's a teacher I can talk to, she's my second parent"). She expanded: "teachers are like your parents because they want to see you succeed in life … they are like your mom and dad helping and guiding you to a better future." Such teacher acts were probably especially meaningful because the girls could not consistently rely on parents/parent-figures due to parental absence or death, or parent complicity in abuse (see Jefferis & Theron, 2015).

Teachers Motivate Girls toward Positive Futures

The girls communicated that their teachers wanted to see them succeed in life, and therefore encouraged them to behave in ways that would lead to their future success. This included guiding the girls to formulate goals. Participant 7 said, "from like primary [school] … they have been teaching us that if you want something, you should set a goal, you should know what you're going to do to achieve that goal … my teachers are big motivators to me …" These goals were typically related to investing in education. For example, Participant 4 explained, "your teacher will [say] 'If you want to be like me … [you] have to go to school'. So that's what makes you realise that school is important." Participant 8 stated, "my teacher challenges me with maths and science so that I can be able to walk on the road to my success."

In the course of motivating the girls teachers nurtured the girls' self-worth, and in doing so amplified girls' belief that they could aspire to transformed futures. For example, participants commented:

"You might say 'this is the most difficult subject in school - I cannot be able to do this!' But, your teacher will [say to you] 'you have that thing you can do it, you have potential and I believe in you' and you will say 'at least someone believes in me' … so school shows us that people can make you to succeed because always we tend to say 'I don't have strength I cannot be able to do this', but when someone comes and says 'you can', that's when you start to believe that you can" [Participant 4].

"When you go to school your teachers are your parents, so they give you knowledge and they help you to be someone else in life, an independent person. That's why I'm always open to learn how to conquer things in life" [Participant 11].

By building girls' self-esteem, teachers also reinforced the very behaviours (e.g. goal setting, planning, and diligence) that they urged girls to adopt if they wanted to improve their prospects and have a better future. This is illustrated by Par-ticipant 10's comment: "I prepare for class, when the teacher asks questions I feel proud about myself to give answers and the teacher gives positive feedback saying that was a good answer."

Teachers Initiate Teacher-Girl Partnerships

Teachers who championed girls' resilience did not wait for the girls to approach them regarding diffi-culties, but recognised when girls were vulnerable and acted on this in ways that supported con-structive coping. For example, Participant 11 ex-plained that her teacher immediately recognises when something is wrong, and then reaches out to her to in order to support her to cope well:

You know like sometimes in school, in class … people tease me … she [teacher] could just call me and say "is anything going on?" […] she said "don't take people that tease you into consideration because they are just making a fool of themselves" … and then she would just say "okay in order for you to smile I'm going to give you an activity to just do, and then you can sit alone, be quiet and just do it, or you can just do it at home and bring it back or just read" … and she helps me a lot because I can forget, like in 2 minutes I can forget that I was even teased because of that moment that I'm with her … she makes me smile [Participant 11].

In another example, Participant 1 reported that teachers reach out and tell students that if they face problems they should approach teachers, "most of our teachers will [say] if you have a problem you have to come to me." She went on to explain that teachers insist on girls talking to them about the difficulties they face, "the teachers will [say] tell me what is your problem and tell me the people who are involved so that I can be able to help you."

Similarly, teachers took action to secure girls' access to protective resources that supported their resilience. For instance, Participant 7 explained that when she was orphaned. Her teacher's introduction to a local support programme enabled her to form supportive connections with local adults: "my teacher … introduced me to Girl-Child when she found out that I don't have parents anymore. So after that Mme [name], she's been there for me."

When girls resisted teacher overtures - typi-cally because they were embarrassed or uncertain - this did not discourage teachers. Participant 5 drew a reluctant girl and a determined teacher (see Figure 2). She explained:

"I have drawn a learner and a teacher, the learner is crying, the teacher is trying to comfort her but she insists on not telling the teacher what's wrong, but because we have caring teachers she [the teacher] insists that the learner should talk to her" [Participant 5].

Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. Because girl-participants were recruited by gatekeepers, girls who are quietly resilient (see Theron, 2016b) might not have been identified and so their insights are not included. Moreover, we included only school-going girls. Should we have included girls who had dropped out of school as well as teachers, we might have uncovered different perspectives regarding whether and how teachers champion girls' resilience. In spite of the limitations, the findings above have important implications for teachers.

Discussion

The purpose of this article included exploring girls' accounts of how teachers (as key social-ecological stakeholders) facilitate resilience, and what insights can be drawn on to develop strategies for teachers to champion resilience. Clearly, teachers do enable resilience. This fits with findings from the greater Pathways study (Liebenberg, Theron, Sanders, Munford, Van Rensburg, Rothmann & Ungar, 2016), the South African Pathways study (Theron, 2016b; Theron et al., 2014; Theron et al., 2013), as well as prior international studies of youth resilience (e.g., Doll et al., 2011; Ungar et al., 2014). Of some concern is that half of the girl participants did not include teachers in accounts of resilience. So, although teachers do enable resilience, their championship of resilience could be more consistent. More consistent championship of resilience could probably be secured by capacitating teachers to enable resilience (Munford & Sanders, 2015; Theron & Theron, 2014).

With respect to the way in which resilience-promoting teachers enable resilience, the findings speak to student-centred teachers. Part of this student-centredness was being empathic and guiding girls through difficulties. This corroborates existing research, which foregrounds supportive teachers as important for young people's resilience (Ferreira & Ebersöhn, 2011; Phasha, 2010; Ungar et al., 2014). Another facet of student-centredness lies in the finding that rural teachers initiate supportive partnerships with girls. This supports studies by Theron and Engelbrecht (2012), as well as Theron and Theron (2014). A third dimension of teacher generosity is found in teacher concern for the futures of the girls they taught. To this end, they urged goal-directed investment in education and reinforced girls' enactment of their advice. As with the above, this reinforces prior understandings of how teachers enable and sustain resilience (Malindi, 2014; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Phasha, 2010).

These findings suggest three strategies which teachers could use to promote resilience (detailed below). Although they are embedded in what rural girls report about their resilience-promoting teach-ers, each is broad enough to be useful to teachers working in rural and/or urban contexts. Similarly, although these findings flow from a study with young people in the Global South, they are broad enough to be useful to teachers working with marginalised young people in the Global North as well.

Pre-Empt Support

Ungar (2013) maintains that a social ecology bears more responsibility for resilience processes that enable young people, than young people them-selves. Part of this responsibility lies in a social ecology providing the resources necessary for young people to achieve functional outcomes (Ungar, 2011). The remaining part of the responsibility also lies with the individual. In this regard, young people are expected to demonstrate agency and negotiate for what they need (Munford & Sanders, 2015). However, it is crucial that a social ecology (including teachers) not only recip-rocates such agency, but also initiates partnerships that provide support for vulnerable young people (Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012).

The Norms and Standards Policy for South African Educators scripts teachers to be pastoral carers who "respond to social and educational problems" (DoE, Republic of South Africa, 2000:18). Implicit in this wording is reactivity, where teachers act in response to the needs of learners. Although such reactivity is important, it camouflages the need for teachers to also proactively enable young people. This has im-portant implications for supporting potentially vulnerable learners, because reserved learners might not always approach their teachers and could possibly remain at-risk if teachers do not reach out to them. Therefore, rural (but also other) teachers can promote young people's resilience by recognising potentially vulnerable learners, and initiating teacher-learner partnerships aimed at providing emotional and pragmatic support to facilitate resilience among learners. More im-portantly, perhaps, is that teachers go beyond initiating support for learners, who appear vul-nerable and begin to agitate for life-worlds that are less likely to put any young person at risk (Theron, 2016b). By lobbying for social change that will result in fewer young people needing to be resili-ent, teachers will have engaged in the 'ultimate championship' of resilience.

Advocate for a Changed Education Landscape

Education is associated with resilience processes of young people both locally (Phasha, 2010; Theron & Phasha, 2015), and internationally (Doll et al., 2011; Masten, 2014; Ungar et al., 2014). When teachers motivate learners to invest in their education to work towards a positive future, they also encourage hope that the adversities learners face can be overcome in the future (Ebersöhn, 2008; Malindi & Machenjedze, 2012; Mosavel et al., 2015; Phasha, 2010; Theron, 2016b; Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012). However, it is not enough for teachers to encourage hope alone, particularly when the quality of education is substandard, especially for those living in rural or disadvantaged areas (Steyn, Harris & Hartell, 2014). If the quality of Basic Education in South Africa remains poor, then motivating young people to invest in their education is setting them up for failure, because below par education is likely to obstruct upward trajectories (Theron, 2016b). With the recent nationwide South African student protests, the need for quality education - including quality basic education - has received increased attention (Petersen, 2015). The cost of tertiary education has become almost unaffordable to disadvantaged stu-dents, who often take longer to complete their studies as a result of substandard literacy and numeracy skills in basic education (Modisaotsile, 2012).

Considering the above, teachers worldwide can promote young people's resilience by be-coming advocates for a changed education landscape, particularly for disadvantaged learners. First, teachers can advocate for better quality basic education and an increase in the appointments and salaries of well-trained teaching staff. Increasing the number of well-trained teaching staff could improve the quality of teaching. Also, well-trained teaching staff are more likely to have the skills needed to cope with educator and concomitant caring roles and therefore be in a better position to provide additional support to learners, particularly at disadvantaged schools (Badat & Sayed, 2014). Second, teachers can advocate for career coun-selling to be made available in South African schools so that young people understand what options they have at their disposal post-school. Maree (2013) advocates for contextually and culturally appropriate career counselling that guides young people towards fitting careers, successful life designs, and opportunities to contribute towards society. Such counselling will facilitate young people's understanding of which school subjects and skills they need to prioritise. This prioritisation is likely to enhance their progress at school as well as post-school. Advocating for better quality education as well as career counselling opportunities might benefit learners by assisting them with realistic avenues to follow in order to achieve their future life-goals and overcome current adversity.

Communicate Constructive Messages

The importance of teacher feedback is well documented (Bansilal, James & Naidoo, 2010; Dowse & Van Rensburg, 2015), but bears repeating, with special emphasis on the importance for young people who are vulnerable. To transcend disadvantage and adversity requires the belief that it is possible (Theron, 2016b). In instances where young people face complex challenges, such as, for example, being economically disadvantaged and a young woman in a community where girls are more vulnerable than boys, affirmative messages become even more important. Jordan (2013) explains that, particularly for women and girls, growth-fostering relationships that build resilience are those that cultivate self-esteem and feelings of self-worth. Teachers are in a key position to facilitate this. Furthermore, Hartling (2008) explained that re-lationally-based self-worth is more important for resilience than achievement-based self-worth. One way of nurturing self-worth through relationships is through feedback. Teachers can, for example, emulate the resilience-promoting teachers' endorse-ment of the girls' constructive engagement in education and other constructive actions, as in the current study. This will likely foster learners' self-worth. The key is thus for teachers to utilise every possible opportunity to provide meaningful positive feedback to learners to nurture their self-worth, and ultimately their resilience.

Conclusion

In this article, we considered what girls' resilience accounts reflect about how teachers (as key social-ecological stakeholders) facilitate resilience and how these insights could be utilised to support teachers to champion resilience. In short, teachers champion resilience when they act in ways that enable their students. These enabling actions in-clude listening and providing guidance, inspiring hope for a better future, and initiating supportive partnerships with students. Essentially these same actions are integral to the resilience-enabling strategies that flow from adolescent girls' accounts of how teachers mattered for resilience, namely pre-empt support, advocate for changed education landscapes, and communicate constructive mess-ages. In other words, and as repeatedly theorised by Ann Masten (2001, 2014), teacher championship of resilience is about the 'ordinary magic' of teacher commitment to everyday, constructive actions that have the capacity to enable young people.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the South African P2R research team and advisory panel for their assistance with participant recruitment and the process of data generation. Also, we express our appreciation to all the girls that participated in this study.

Note

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Badat S & Sayed Y 2014. Post-1994 South African education: The challenge of social justice. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 652(1):127-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716213511188 [ Links ]

Bansilal S, James A & Naidoo M 2010. Whose voice matters? Learners. South African Journal of Education, 30(2):153-165. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/236/177. Accessed 31 May 2017. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2014. Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). London, UK: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dass-Brailsford P 2005. Exploring resiliency: academic achievement among disadvantaged black youth in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 35(3):574-591. [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C & Bhana D 2012. Voices of women teachers about gender inequalities and gender-based violence in rural South Africa. Gender and Education, 24(5):499-514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2011.645022 [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE), Republic of South Africa 2000. National education policy act (27/1996): Norms and standards for educators. Government Gazette, 415(20844):4 February. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/20844.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2017. [ Links ]

Doll B, Jones K, Osborn A, Dooley K & Tuner A 2011. The promise and the caution of resilience models for schools. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7):652-659. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20588 [ Links ]

Dowse C & Van Rensburg W 2015. "A hundred times we learned from one another": Collaborative learning in an academic writing workshop. South African Journal of Education, 35(1):Art. # 860, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201503070030 [ Links ]

Ebersöhn L 2007. Voicing perceptions of risk and protective factors in coping in a HIV&AIDS landscapes reflecting on capacity for adaptiveness. Gifted Education International, 23(2):149-159. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/026142940702300205 [ Links ]

Ebersöhn L 2008. Children's resilience as assets for safe schools. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(1):11-17. [ Links ]

Ferreira R & Ebersöhn L 2011. Formative evaluation of the STAR intervention: improving teachers' ability to provide psychosocial support for vulnerable individuals in the school community. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(1):63-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2011.575549 [ Links ]

Guillemin M 2004. Understanding illness: Using drawings as a research method. Qualitative Health Research, 14(2):272-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303260445 [ Links ]

Guillemin M & Drew S 2010. Questions of process in participant-generated visual methodologies. Visual Studies, 25(2):175-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.502676 [ Links ]

Hartling LM 2008. Strengthening resilience in a risky world: It's all about relationships. Women & Therapy, 31(2-4): 51-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802145870 [ Links ]

Heath MA, Donald DR, Theron LC & Lyon RC 2014. AIDS in South Africa: Therapeutic interventions to strengthen resilience among orphans and vulnerable children [Special issue]. School Psychology International, 35(3):309-337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034314529912 [ Links ]

Holt A 2016. Adolescent-to-parent abuse as a form of "domestic violence": A conceptual review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(5):490-499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015584372 [ Links ]

Jefferis TC & Theron LC 2015. Community-based participatory video: exploring and advocating for girls' resilience. Perspectives in Education, 33(4):75-91. [ Links ]

Jewkes R, Gibbs A, Jama-Shai N, Willan S, Misselhorn A, Mushinga M, Washington L, Mbatha N & Skiweyiya Y 2014. Stepping stones and creating futures intervention: shortened interrupted time series evaluation of a behavioural and structural health promotion and violence prevention intervention for young people in informal settlements in Durban, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 14:1325. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1325 [ Links ]

Johnson B & Lazarus S 2008. The role of schools in building the resilience of youth faced with adversity. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(1):19-30. [ Links ]

Jordan JV 2013. Relational resilience in girls. In S Goldstein & RB Brooks (eds). Handbook of resilience in children (2nd ed). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4 [ Links ]

Kruger L & Prinsloo H 2008. The appraisal and enhancement of resilience modalities in middle adolescents within the school context. South African Journal of Education, 28(2):241-259. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/173/108. Accessed 29 May 2017. [ Links ]

Liebenberg L, Theron L, Sanders J, Munford R, Van Rensburg A, Rothmann S & Ungar M 2016. Bolstering resilience through teacher-student interaction: Lessons for school psychologists. School Psychology International, 37(2):140-154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315614689 [ Links ]

Malindi MJ 2014. Exploring the roots of resilience among female street-involved children in South Africa. Journal of Psychology, 5(1):35-45. Available at http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JP/JP-05-0-000-14-Web/JP-05-1-000-14-Abst-PDF/JP-5-1-035-14-116-Malindi-M-J/JP-5-1-035-14-116-Malindi-M-J-Tx[4].pdf. Accessed 29 May 2017. [ Links ]

Malindi MJ & MacHenjedze N 2012. The role of school engagement in strengthening resilience among male street children. South African Journal of Psychology, 42(1):71-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631204200108 [ Links ]

Mampane R & Bouwer C 2006. Identifying resilient and non-resilient middle-adolescents in a formerly black-only urban school. South African Journal of Education, 26(3):443-456. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/89/47. Accessed 28 May 2017. [ Links ]

Maree JG 2013. Latest developments in career counselling in South Africa: towards a positive approach. South African Journal of Psychology, 43(4):409-421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246313504691 [ Links ]

Masten AS 2001. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3):227-238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227 [ Links ]

Masten AS 2014. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Mitchell C, Theron L, Stuart J, Smith A & Campbell Z 2011. Drawings as research method. In L Theron, C Mitchell, A Smith & J Stuart (eds). Picturing research: Drawing as visual methodology. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Modisaotsile BM 2012. The failing standard of basic education in South Africa. POLICYbrief, 72:1-7. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/962d/0e044538cb77a843fde686b02528842d9c25.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2017. [ Links ]

Mosavel M, Ahmed R, Ports KA & Simon C 2015. South African, urban youth narratives: resilience within community. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20(2):245-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.785439 [ Links ]

Munford R & Sanders J 2015. Young people's search for agency: Making sense of their experiences and taking control. Qualitative Social Work, 14(5):616-633. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325014565149 [ Links ]

Panter-Brick C 2015. Culture and resilience: Next steps for theory and practice. In LC Theron, L Liebenberg & M Ungar (eds). Youth resilience and culture: Commonalities and complexities. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Petersen T 2015. #FeesMustFall movement a 'wake up call' - Jonathan Jansen. News 24, 5 November. Available at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/FeesMustFall-movement-a-wake-up-call-Jonathan-Jansen-20151105. Accessed 12 November 2015. [ Links ]

Phasha TN 2010. Educational resilience among African survivors of child sexual abuse in South Africa. Journal of Black Studies, 40(6):1234-1253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934708327693 [ Links ]

Saldaña J 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

Schoeman S 2015. Towards a whole-school approach to the pastoral care module in a Postgraduate Certificate of Education programme: a South African experience. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1):119-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.892576 [ Links ]

School Terms South Africa 2016. 2016 school terms and holiday dates. Available at http://www.schoolterms.co.za/2016.html. Accessed 31 May 2017. [ Links ]

Steyn MG, Harris T & Hartell CG 2014. Institutional factors that affect black South African students' perceptions of Early Childhood teacher education. South African Journal of Education, 34(3): Art. # 850, 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201409161107 [ Links ]

Theron LC 2016a. The everyday ways that school ecologies facilitate resilience: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology International, 37(2):87-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315615937 [ Links ]

Theron LC 2016b. Toward a culturally and contextually sensitive understanding of resilience: Privileging the voices of black, South African young people. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(6):635-670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415600072 [ Links ]

Theron LC & Engelbrecht P 2012. Caring teachers: Teacher-youth transactions to promote resilience. In M Ungar (ed). The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Theron L, Liebenberg L & Malindi M 2014. When schooling experiences are respectful of children's rights: A pathway to resilience. School Psychology International, 35(3):253-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723713503254 [ Links ]

Theron LC & Phasha N 2015. Cultural pathways to resilience: Opportunities and obstacles as recalled by black South African students. In LC Theron, L Liebenberg & M Ungar (eds). Youth resilience and culture: Commonalities and complexities. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Theron LC & Theron AMC 2010. A critical review of studies of South African youth resilience, 1990-2008. South African Journal of Science, 106(7-8):1-8. [ Links ]

Theron LC & Theron AMC 2014. Education services and resilience processes: Resilient black South African students' experiences. Children and Youth Services Review, 47(3):297-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.10.003 [ Links ]

Theron LC, Theron AMC & Malindi MJ 2013. Towards an African definition of resilience: A rural South African community's view on resilience Basotho youth. Journal of Black Psychology, 39(1):63-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798412454675 [ Links ]

Ungar M 2008. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work, 38:218-235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [ Links ]

Ungar M 2011. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x [ Links ]

Ungar M 2012. Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience. In M Ungar (ed). The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Ungar M 2013. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3):255-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805 [ Links ]

Ungar M, Russel P & Connelly G 2014. School-based interventions to enhance the resilience of students. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 4(1):66-83. https://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v4n1p66 [ Links ]

Van Rensburg A, Theron L, Rothmann S & Kitching A 2013. The relationship between services and resilience: A study of Sesotho-speaking youths. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 25(3):287-308. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation 2015. Gender, equity and human rights. Available at http://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/understanding/gender-definition/en/. Accessed 8 November 2015. [ Links ]