Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.37 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n1a1250

ARTICLES

e-Portfolio as reflection tool during teaching practice: The interplay between contextual and dispositional variables

Arend CarlI; Sonja StrydomII

IDepartment of Curriculum Studies, Faculty of Education, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. aec2@sun.ac.za

IICentre for Learning Technologies, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on an e-portfolio pilot initiative at the Faculty of Education at a South African university and aims to determine whether the theoretical underpinning and expectations of an e-portfolio aligns with the current practices and attributes of students' training during school practicum as teachers at a South African university. In the South African context, e-portfolios are increasingly being considered in teacher training programmes, to enable student teachers to reflect in, on and about practice in a structured way, whereby they demonstrate their growth and development as professionals. A self-selected sample of 11 student teachers placed in different urban and rural school contexts were provided with tablets and data bundles. Equipped with varying digital skills, daily reflections and regular online interaction with peers and project members was expected. Data gathering was done by means of semi-structured interviews which were analysed by means of framework analysis. Results suggest that student teachers still require support in reflective writing; that the social and collaborative aspects of e-portfolio use within the given context is underdeveloped, and that the level of digital skills of students will impact the potential success of the integration of e-portfolios as reflective tools. This paper contributes to the growing interest in South African literature regarding the use of e-portfolios for teacher training, by highlighting contextual and dispositional variables as essential considerations before adopting such a learning approach as part of teacher training.

Keywords: digital literacy; e-portfolio; online collaboration; reflection; student-centred learning; teacher training

Introduction

Students in the twenty-first century are surrounded by direct access to mass communication and information and rapidly developing technologies. Such a dynamic context creates opportunities for students to become more aware of skills and attributes needed to function optimally in modern society. As a result, higher education is challenged to provide more learning opportunities related to the development of problem-solving and thinking skills, and, to a lesser degree, to the memorisation of content, which suggests that knowledge creation and application ought to replace mere knowledge recall (Rodgers, Runyon, Starrett & Von Holzen, 2006). Twenty-first century students are expected to develop meta-cognitive attributes, to demonstrate more criticality, creativity and innovation, and to be able to collaborate and communicate in diverse contexts (Jimoyiannis, 2012). Providing students with the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge and skills paves the way for reflective practices by which "experiences are turned into learning" (Steur, Jansen & Hofman, 2012:267). These types of learning experiences are often included in the pursuit of the development of graduate attributes that endorse moral citizenship, scholarly skills, and lifelong learning, amongst other notions (Steur et al., 2012). By opening the minds of students to the necessity of lifelong learning, awareness is raised for the possibility of learning within the formal curriculum, the co-curriculum, the world of work and the community (Candy, 1995).

South Africa, like many other countries, realises the importance of investigating all possible avenues of increasing learning in order to optimise the potential of their students. This vision of increasing learning can also be achieved through the integration of information communication technology (ICT) in the curriculum. For example, Tedla (2012:199-200) makes the case that ICT can promote the quality of education by creating an effective teaching-learning atmosphere, in that it promotes new understandings in the use of ICT in the classroom. These new ways of teaching and learning can support students in developing new knowledge and appropriate skills.

Mapped against this background, it is expected that higher education institutions ought to be encouraged to regularly explore the diverse needs of students by replacing an 'inside-in' paradigm (i.e. decision-making resides with the institution or co-ordinators) with an 'inside-out' paradigm (i.e. emphasis is placed more on viewpoints and perceptions of students). Such a student-centred approach calls for deeper levels of learning, where responsibility and accountability are expected and where perceptions of autonomous learning are encouraged (Lea, Stephenson & Troy, 2003). Within such a context, reflective practice is regularly portrayed as an effective mechanism in encouraging professional self-evaluation and adaptation (Meierdirk, 2016).

With regard to teacher training, teachers are, in most cases, required to reflect on their practice and to develop a portfolio of evidence (Tarrant, 2013). The motivation to encourage reflection for both pre-service and in-service teachers stems from the potential opportunities for teachers to use such approaches to learn from reflective practice and develop their own personal theories, to utilise such practices as agents of change, to enhance criticality and problem-solving, to guide teachers towards their passion, and to create opportunities for more autonomy, whereby a more structured approach towards learning and teaching is adopted (Malthouse & Roffey-Barentsen, 2013; Pelech, 2013).

Of note is that it seems, increasingly, as if inservice teachers participate in online communities for collaboration, support and professional learning (Anwaruddin, 2015).

Therefore, in terms of reflective learning and continuous professional development, e-portfolios could be utilised as a way of demonstrating the acquisition of certain skills and attributes. An e-portfolio is an electronic collection of evidence to demonstrate learning over a selected period. Evidence may include, but is not limited to photos, videos, research projects, interviews and reflective writing. Such evidence could be related to specific academic experiences or as evidence of lifelong learning. Key to appropriate e-portfolios practices remains the user's reflection on evidence selected, a demonstration of what has been learnt during the learning process, as well as the level of social interaction between the user and other significant role players such as peers, facilitators or teachers (Barrett, 2011).

This paper aims to clarify whether the theoretical underpinnings of sensible e-portfolio use (Barrett, 2011) aligns with current institutional expectations, as well as school visit practices and attributes of students during a school practicum period of pre-service teachers at a South African university. The paper is divided into the following sections: firstly we provide an overview of the requirements of teacher practice and reflection and make reference to the use of e-portfolios in higher education. This is followed by the methodology, results and discussion, and finally, the conclusion.

Teaching Practice and Reflection The policy on "Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications" (Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa, 2015:12) stipulates that competent learning is always a mixture of the theoretical and the practical. In effect, competent learning represents the acquisition, integration and application of different types of knowledge. Each type of knowledge, in turn, implies the mastering of specific related skills. The types of learning associated with the acquisition, integration and application of knowledge for teaching purposes are disciplinary learning, pedagogical learning, practical learning, fundamental learning and situational learning (Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa, 2015:12). With regard to practical learning, the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) is clear where it states:

Practical learning involves learning from and in practice. Learning from practice includes the study of practice, using discursive resources to analyse different practices across a variety of contexts [.... ] Learning in practice involves teaching in authentic and simulated classroom environments. Work-integrated learning (WIL) takes place in the workplace and can include aspects of learning from practice (e.g. observing and reflecting on lessons taught by others), as well as learning in practice (e.g. preparing, teaching and reflecting). Practical learning is an important condition for the development of tacit knowledge, which is an essential component of learning to teach (Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa, 2015:12).

It is within these practical types of learning that this study is positioned, as students currently need to compile a paper-based portfolio and reflect continually, based on their learning experience(s) during the teaching practice time at the school. Providing students with the opportunity to reflect via e-portfolios and adopting an e-portfolio pedagogical approach provided us with valuable insights into commonalities and tensions between the two different tools (paper-based vs e-portfolio) used.

With regard to the notion of reflective practice, complexity arises with regards to the way in which confusion in the literature exists in terms of what underpins reflection epistemologically. For instance, the work of Dewey (1938) states that reflection is emotive of nature with impulsive tendencies, Schon (1975) makes the case that reflection is one way of learning whereby the institution benefits, whilst Boud, Keogh and Walker (1985) postulate that reflection provides opportunity to recapture an experience by means of individual learning. The explanation of reflection thus moves from the collective to a more individual or private action (Finlayson, 2015). Such an explanation, however, poses interesting challenges, since one of the critical dimensions of e-portfolios remains social interaction on reflection and choice of artefacts (Joyes, Gray & Hartnell-Young, 2010: 16).

From a theoretical perspective, Schön is one of the prominent theorists regarding reflective practices. Schön (1995) distinguishes between "reflec-tion-in-action" and "reflection-on-action"; the former suggesting an immediate conscious action or reaction taken in the moment, and the latter requiring a continuous process of evaluation, review and adaption after the actual event. "Reflection-on-action" calls for the opportunity to reflect on a challenge or problem in order to cumulatively build new knowledge to solve such problems (Meierdirk, 2016).

Reflection could also be explained as "the process of learning through and from experience towards greater insights of self or practice" (Finlay, 2008:1). It is clear that learning remains central to such an approach, whereby a particular experience within the educational context contributes to an opportunity for the teacher to grow in understanding and knowledge. In terms of teacher education, reflective practice then fulfils the role of creating further opportunities for pre- and inservice teachers to learn from their particular educational experiences (Meierdirk, 2016).

However, the notion of reflection, reflexivity and reflective practice is used interchangeably in the literature. Bolton (2014) distinguishes between reflection, reflexivity and reflective practice by suggesting that reflection provides opportunity for an in-depth analysis or examination of an event or encounter; reflexivity is an attempt to find approaches whereby one's beliefs, values and attitudes are interrogated; whilst reflective practice creates opportunity to marvel at one's work, the world, and oneself.

It ought to be acknowledged that the definition and meaning of reflection changed significantly over time. Despite a number of definitions available, in the context of this study, we would like to adopt the definition of Sellars (2014:2) who states:

[reflection] is the deliberate, purposeful, meta-cognitive thinking and/or action in which teachers engage in order to improve their professional practice.

Defining reflection in teacher education focuses on the attempt to transform or change existing actions and practices (i.e. teaching) of student learning (LaBelle & Belknap, 2016, Schön, 1990). According to Schön (1990), reflection-in-action therefore requires the teacher to think on his or her feet, in an immediate situation where action is required, while reflection-on-action provides the teacher with the opportunity to reflect on such an action after the event took place (Bolton, 2014; Malthouse & Roffey-Barentsen, 2013).

Reflection aids the teacher in becoming critical about their own classroom practices, to identify and develop needs and to acknowledge strengths (Tarrant, 2013). As with all other careers, pre-service teachers start as novices, and according to Tarrant (2013), will move towards advanced beginner, competent performer, proficiency and then expert level. Reflective practice thus paves the way for teachers to express their own beliefs regarding learning and teaching, by critically exploring actions and proposing alternative actions for the future. Teachers therefore collect data about their practice, make use of such evidence to decide on future actions, and then adopt changes or not accordingly (Farrell & Mom, 2015).

However as a note of caution, despite the calls for reflective practices in teacher training, the critical question remains as to how students could improve, based on such reflections and insights. Such improvements or adaptations could only be of value when students have knowledge about self-development and growth. However, students rarely have professional attributes fully developed whilst in pre-service education, where such expectations pose a number of challenges and critical questions about the true ability to improve on learning experiences (Meierdirk, 2016). This challenge speaks directly to the one critical dimension of e-portfolios absent in the current context of teacher practice: learning from each other by means of peer feedback and support.

e-Portfolios in Higher Education A number of factors contribute to the interest in e-portfolios in higher education. The main reasons are related to the impact of pedagogical changes in higher education, whereby a student-centred approach and more active learning experiences are encouraged (Joyes et al., 2010). The rapid growth of technologies for learning - and certainly also of social media platforms - gives students the opportunity to document and publish across a number of platforms that contribute to the accessibility of e-portfolios to different educational needs. In addition, higher education institutions are under increased pressure to provide evidence of skills and competencies acquired by students within the twenty-first century (Clark & Eynon, 2009). Barrett (2000) suggests that portfolio development involves more than just the role of technology and an expected product; rather, prominence should be given to the process of learning during e-portfolio development, which includes constructivist actions, reflection and collaboration (Jimoyiannis, 2012). In order to achieve this, emphasis should be placed on developing a shared understanding of what we define as e-portfolios and what we expect to achieve from such a learning processes. The question can rightly be asked as to whether such an approach aligns with current teacher training courses and institutional expectations. This view is supported by Roder and Brown (2009), who contend that research highlights the lack of common understanding with regards to the use and purpose of e-portfolios in education. It is especially evident that a lack of understanding exists regarding the users' relationship with data and the social-cultural influences related to e-portfolio use in educational practices. At a conceptual level, an institutional paradigm shift is required to move e-portfolio integration beyond the micro-level (semester or unit of work) towards a meta-level, whereby such a learning process is valued as a process of holistic learning development at a university (Challis, 2005).

At an operational level, one way of integrating such a learning approach could be to replace existing paper-based portfolios with electronic portfolios. Challis (2005), however, cautions that although common references between paper-based and electronic portfolios exist, there are distinct differences in the approaches to the learning process and learning outcomes. Traditional paper-based portfolios provide students with the opportunity to collect artefacts and showcase them in a format of their choice. Reflections and what they have learnt from the process are also included in the product. The student reflections and what has been learnt from particular artefact selection and associated learning experiences are essential to such a portfolio. Although displaying these similar characteristics, e-portfolios generate a more dynamic learning space, where artefacts are purposefully collected and integrated into the portfolio with the opportunity to act immediately on feedback from the online community involved in the project (Challis, 2005). Such an electronic-based portfolio is managed by the student, whereby the choice and level of access to the portfolio is determined by the user. Web 2.0 technologies provide students with the opportunity to archive artefacts, insert hyperlinks, publish, share, communicate and collaborate where appropriate (Jimoyiannis, 2012). Furthermore, if there is access to evidence of other students' learning processes, new learning spaces can be created in which students not only receive confirmation of their own learning processes, but are also exposed to other experiences and practices that may offer deeper professional learning.

Barnstable (2010) has argued that e-portfolios could provide prospects of more integrated learning experiences in terms of employability and work-based learning, as additional support could be provided to learners, relating to their transition from formal education to the workplace. This view is highlighted by the added value and relevance placed on lifelong and life-wide learning within the current higher educational context. Within this context, and taking into account the emphasis placed on the learning process, students are provided with the opportunity to develop their own personal learning goals and to potentially experience deeper levels of learning through critical reflection (Barnstable, 2010). Portfolios therefore provide students with the ability to cohesively integrate all their learning experiences into a meaningful unit, that might contribute to their own personal and professional development (Housego & Parker, 2009). The e-portfolio learning process and subsequent product can play a significant role in terms of employability and continuous professional development, whereby the career development process (and not particular learning outcomes) become the driving aspect of portfolio development (Garis, 2007). Thus, an opportunity is created to align academic and professional learning outcomes and achievements in formal education closely with the world of work (Jimoyiannis, 2012).

The current study therefore aims to explore the current alignment and tensions between existing pre-service teacher school visit expectations regarding the development of a portfolio of evidence and the suggested pedagogical approaches associated in the literature regarding the development of e-portfolios as reflective tools.

Methodology

Forming part of the Teaching and Learning module (Teaching Practice) in the Post Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) programme, students are expected to develop a paper-based portfolio during their teaching practice at schools, which requires them to write a weekly reflection about teaching, learning and assessment practices, and a reflective essay of the whole school visit at the end of the school practicum. Students are encouraged to use different forms of documentation and artefacts as evidence, but are not allowed to use mobile devices in the classroom (Rhodes, 2016).

Although 195 students enrolled in the programme, a self-selected sample of 11 students participated in the project due to our aim to gain in-depth insight into the chosen phenomenon, namely, the use of e-portfolios as reflective tools during teacher practice. As students could volunteer to participate in the project, we had no control over how representative the cohort would be with regard to race, gender and personal attributes. As it turned out, of the 11 participants, there were nine females (three Coloured students) and two White male students, who all received a tablet as well as data bundles to ensure connectivity. For the purpose of the study, the participating students were familiarised with the devices, introduced to the notion of e-portfolios, assisted in creating blogs to serve as e-portfolio platforms, guided in how to collect artefacts and how to reflect appropriately on the learning experience, as well as to comment on those of others.

Methodological Approach

The investigation was undertaken by means of a case study approach within a qualitative research paradigm, as we wanted to interpret and understand the students' experiences in a real-life and specific context. According to Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2011:289) a case study "provides a unique example of real people in real situations enabling readers to understand ideas more clearly". A case study also helps one to observe effects in real contexts and are thus strong on reality (Cohen et al., 2011:293). Due to the nature of a case study and the non-probability sample (Denscombe, 2003:12), results are not generalisable, but, we make the case for transferability to an audience, identifying links between aspects of this study and their own experiences.

Data Collection

Two semi-structured focus group interviews, where participants were selected not to be representative, but rather purposive (Rabiee, 2004), were conducted to gain feedback on participants' experiences and opinions (Cohen et al., 2011:411; De Vos, Strydom, Fouché & Delport, 2005:304; Liamputtong, 2011:4-5) within a context where the researchers still had a level of control over the flow of the discussion. Such a data collection approach can "provide a window into the complexities and richness" of a chosen phenomenon (Liamputtong, 2011:182). Guided by literature (Barrett, 2011; Challis, 2005; Garrett, 2011), the requirements of the above-mentioned module, and the aim of the project, the interview schedule covered aspects such as reflections, training, professional development and the social dimensions of the e-portfolio.

Data Analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were analysed by means of "framework analysis" (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994) whereby the researchers approached the data through a number of stages: familiarisation (listening to audio files and reading transcripts in their entirety a number of times for major themes to emerge); identifying a thematic framework (the formation of descriptive statements); indexing (sifting data by highlight and sorting); charting (lifting quotes from original context and rearranging them); and mapping and interpretation (managing data). Since the interview schedule was guided by literature, module requirements and the aim of the project, it came as no surprise that themes emerged both from the research questions as well as the narratives of participants (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994).

Results and Discussion

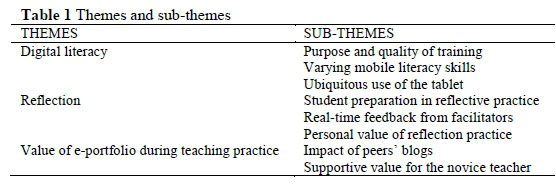

Themes related to digital literacy, reflection and the potential value of the e-portfolio as a tool within teacher practice, emerged. Sub-themes associated with digital literacy highlighted the purpose and quality of training, the varying levels of mobile literacy skills of participants and the ubiquitous nature of the tablet during school visits. Related to the notion of reflection, participants commented on their own level of preparation in terms of writing reflectively, the need to receive real-time feedback from facilitators during the school visit period, as well as the personal emphasis placed on the value of reflection by the participants. Finally, in terms of the value of the e-portfolio as reflective tool, sub-themes related to the value of access to peers' blogs (e-portfolios), as well as the value of this approach in terms of supporting the novice teacher, emerged.

Digital Literacy

Participants had varying levels of digital literacy skills and therefore their experiences in using the tablets also varied.

Purpose and quality of training

The overall impression was that the facilitators tried to do too much in one session and this created cognitive overload. One respondent commented:

... it was overwhelming because of so much information. It was a whole new thing for me, even though I had my own tablet. I'm still playing around and discovering new things. So it was an overload of information.

Another respondent suggested that this overload could be prevented by using a step-by-step approach:

I would definitely recommend that like when we had that first training session, then you'd send us all to go and complete our blogs and then when we come back to say okay, this is how wanted to invite people.

There was a general view that the follow-up support also needed to be addressed as the students wanted more support from the facilitators. This is evident in the following extract:

I think a good idea would be after the first week of having the tablets and of blogging, we have another session, training session and we then can ask questions that have arisen from that experience. I think it would have been nice if we had a session after the first three weeks as well, four weeks as well, just to recap on what it means to be a critical friend.

It is clear that the participating students valued the importance of the training session, but that such training should be well-planned in terms of sus-tainability and continuous support during the school visit period as well. This of courses raises interesting questions regarding continuous support of large student cohorts adopting an e-portfolio approach. To simplify complexities, it remains imperative that the selected tools and platforms selected can be used intuitively and are easy to maintain (Challis, 2005; Jimoyiannis, 2012). Although it is important to provide students with the necessary technical skills, special care should be taken to prevent technologies from dominating their time and attention, but rather that the learning processes ought to be carefully explained and scaffolded (Challis, 2005).

Varying mobile literacy skills

There were varying skills levels in the use of technology, ranging from not very literate, to being very able and technically skilled. Some of the students initially lacked mobile literacy skills, but they improved their skills through being involved in the project:

"... like I said, I am technologically disabled, but I have improved during those nine weeks, using the e-portfolio..." [all sic]

Some students struggled with blog creation:

"So blogger, it's not very complicated if you know what's going on. But the whole thing is we didn't know what was going on. So you literally just tried and failed and tried and failed and then hopefully, you succeeded after a while" [all sic].

Others, however, were able to do it quite easily:

"... and then setting up the blog - it wasn't that difficult. I thought it was going to be worse. I didn't encounter too many difficulties" [all sic].

One of the challenges of such an initiative is not to make assumptions regarding student digital literacy skills (Brown, 2012), but to take care in establishing the current skills levels of students before such a project is implemented. The so-called digital divide should be carefully considered and care should be taken in addressing any previous use of mobile devices and social practices for learning (Czerniewicz & Brown, 2013). By considering differentiated training and support, facilitators can address such issues. Also of note in the current study remains the fact that students are, in general, not allowed to use mobile devices during classroom visits or observations. This poses the necessity to not only pay attention to mobile literacy skills, but also to clarify the role of mobile devices during school visits, it's appropriateness of use, and also the guidance and training of student teachers to use such resources appropriately within the school context.

Ubiquitous role of the tablet

The ubiquitous nature of the tablet was highly valued. In this regard, one respondent's comment was representative of the whole group:

"It was portable for me. I could carry it everywhere. When I think of something or I see something happening at school, then I don't have to go write it down because sometimes you don't have the time to go write something or you don't have a pen and paper. So you can just take out your tablet, and just type" [all sic].

The classroom use, i.e. the creative use of the tablet for especially references, e-books, capturing data and creation of artefacts was also highly rated:

"I use my tablet a lot for research. I would be presenting in class and I'd have the tablet open next to me. If somebody asked me a question, in English for example, very easy, very quick to define a word - the tablet itself enriches your ability to teach. It gives your learners a better experience by enabling you to give them more content and that really helped me. I used it a lot for when something was written on the board and I know that the teacher would wipe it off. I would take a picture of it and then plan a lesson or write a reflection and think about the stuff that happened in the lesson ... the reflection of the lesson itself. I would just take a picture" [all sic].

It is clear that respondents experienced the value of the tablet as a supportive tool to facilitate effective and quality teaching and learning (Murphy, Farley, Lane, Hafeez-Biag & Carter, 2014). In order for students to use these devices optimally and sensibly in work-integrated learning opportunities, both digital literacies and mobile learning literacies need to be developed (Ng, 2013), where students are enabled to develop an advanced level of criticality in terms of the socio-emotional, cognitive and technical use of such devices within the workplace. Within this context, it is important to establish current institutional requirements regarding the use of mobile devices during lesson observations. In the context of the current study, students are discouraged to access mobile devices during observations, which suggest tension and the necessity of further discussions regarding approaches whereby students could continuously observe lessons in a professional and sensible way, whilst being allowed to use such mobile devices for learning.

Reflection

In terms of reflection, participants made reference to the preparation and training they received in terms of reflective writing, the importance of continuous facilitator feedback, and the personal value they attributed to the reflective practices.

Student preparation in reflective practice

There were varying responses regarding the students' preparedness and ability to write reflections. Initially, the participants had difficulty in writing reflections - they were more inclined to write diaries:

"I don't know - I observed that a lot of us seemed to be doing a journal in the beginning and only after ... I think, we got messaged that it's not meant to be a journal. You 're meant to actually think about what you've learnt. Then everyone was like oh right. So it might have been nice to have one or two more examples and say this is what it is, this is what it's not" [all sic].

To complicate matters further, it seemed as if students were confused with academic writing styles and using a blog to reflect. This suggests that care should be taken in clearly explaining to students the purpose of a blog as a chosen online platform, and not creating an expectation of "blogging" as reflected within the social media context:

"... and also, I had a bit of a problem with the style of how to reflect because here, in an academic setup you are told okay, you need to structure it academically, it needs to be coherent. It needs to have this structure, where in a blog - a blog is a lot more conversational. It's a lot more informal. So while I was writing my blog I kept on wondering [...] may I be informal or should I conform to the academic structure within the university? So, also that question I was unsure of [all sic].

What was evident from the investigation was the fact that some students found it challenging to comment on reflections, due to the often personal nature of experiences during school practice. This poses interesting questions regarding the notion of collaboration and social interaction within an e-portfolio paradigm, as well as the means by which students are prepared in commenting on reflections:

... and then also I feel like how do you really comment on someone's personal experience? Like if you say you've had a bad day, it's hard to say: 'well, maybe if you did this and this and this and this and this, you will have a better day.' You just want to be like: 'okay, she's reflecting.' So I think reflection is such a personal thing. How do you really comment on that to say, ' you know, that's a bad reflection and this is a good one? ' [all sic]

In terms of supporting students in reflective writing practices, Parsons and Stephenson (2005) makes the case for structured support in guiding students on how to reflect. It is argued that reflection is not merely a process of deciding whether a learning encounter was successful, but rather also a process of exploring possible reasons for such an outcome. A clear understanding of the level of reflection that is required from students as well as whether such an approach is appropriate enough to promote sufficient practice, remain important points of discussion with faculties of education (Parsons & Stephenson, 2005:98). The true nature of reflection, and the purpose of enhancing practice, should not be overwhelmed by mechanisms of bureaucracy. Of particular interest remains the challenges students experience in commenting on peers' reflections. As mentioned previously, one of the key criteria of an e-portfolio remains the opportunity of peers to comment on and the prospect of the user to be able to react to feedback, and amend posts accordingly (Barrett, 2011). If the case is made for the use of e-portfolios in its truest sense as a potential vehicle to promote reflection in teacher education, discussions should take place in terms of the notion of an online community of practice (Gunawardena, Hermans, Sanchez, Richmond, Bohley & Tuttle, 2009), online collaboration and communication, as well as the ways in which such an approach might be conceptualised and promoted within current institutional practices.

Real-time feedback from facilitators

The participating students indicated that more realtime feedback from the facilitators would have been helpful:

... maybe a little bit more feedback would have been helpful, because I didn't get any comments for like the first three weeks [all sic]. I think it would have been nice if we had a session after the first three weeks as well, four weeks as well, just to recap on what it means to be a critical friend. Because, I never thought about going back to those papers and thinking about what it means to be a critical friend, I would have liked a comment from you guys, because I got comments from the other students [all sic].

The importance of continuous support mentioned earlier is further emphasised here. Students expect facilitators to provide technical assistance, as well as continuous professional feedback, so that they know they are on the right track. In addition, it is crucial that facilitators become active members of the online community of practice and contribute regularly to the online discussions and feedback. The facilitator can therefore also become a critical friend in the learning process, whereby students receive feedback at different levels that might contribute to the reconceptualisation of learning and lifelong learning (Joyes & Smallwood, 2011).

Personal value of reflection practice

Although the students found it challenging to reflect in the true sense of the word, they did, at a conceptual level, appreciate the practice of reflection. The following comment supports this statement:

I just wanted to say reflection like the weekly reflections were really helpful especially when you 're setting up your final reflection and not having to write your weekly reflection at the end of the practice. But I do believe reflection is an amazing thing; and like I say, you can't grow and you can't push yourself or challenge yourself if you don't think back. I could write that down for me to learn from again, when I go back to teaching. So it made me see the process how I grew. That was good about doing weekly reflections" [all sic].

One participant said: "It really helps you to see your own personal growth as a teacher [... ] I think the act of reflection is really a good idea [... ] I think we should use that in everyday life [. ] because you are not going to grow as an individual."

Students realised that reflection is not merely the act of keeping a diary, but creates an opportunity to observe personal growth through the process of reflective practices. The development of such reflective skills are often attributed to the ability to "learn how to learn", whereby students' real-life experiences are transformed into learning (Bourner, 2003:267). It requires student teachers who pay careful attention to the learning design and appropriate guidance in terms of scaffolding and criticality (Ash & Clayton, 2009).

Value of E-Portfolio during Teaching Practice E-portfolios were generally viewed as valuable in terms of having access to peers' blogs (reflections), as well as the value, in terms of professional development for the novice teacher.

Impact of peers' blogs

Peers' reflections proved a valuable resource which provided students with the opportunity to learn from each other, as well as not to feel alienated by being placed individually in certain schools:

Well, when I saw people doing things, like I saw you adding photos and I saw your sound clip, I was like, 'oh, I can actually do that!' I found actually with reading all of the people's blogs - because I was in XXXX, so I'm in the middle of nowhere. I actually came home; I didn't go home for two months. So I didn't see anybody for that time and it was nice to read everybody's blogs because you know that you 're on the right track. You 're doing what you're supposed to do.

By reading the descriptions and reflections on experiences of participants at other schools, they gained insight into other contexts, which they normally would not have had the opportunity to experience:

It helped me a lot to realise what type of school I wanted to chase [unclear], because I was quite jealous of some of the other peoples' experiences. Whereas I find a lot of my reflections were really negative, which I'm quite - spyt my (sorry) - and when I read the other peoples' blogs, I was quite jealous of their experience because they had like sports day, inter-schools and school spirit and you know, it was easy. They had whiteboards in every class and access to internet in the class and whatever. I didn't have that so it basically helped me to realise that I don't want to be in a school like this is [all sic]. Another participant commented: "It doesn't matter where you are, some struggles stay the same" [all sic].

An added value to the e-portfolio experience was the notion of peer support within the online community. Twenty-first century students often prefer working in groups, where peer collaboration is encouraged, and where they can draw their own conclusions (Barnstable, 2010; Rodgers et al., 2006). Group work suggests a learning context where students are provided with the opportunity to develop metacognitive skills and attributes, to collaborate within different contexts and communicate in a sensible way (Jimoyiannis, 2012). As mentioned previously, this approach, however, poses interesting challenges to the monitoring and standardisation practices of institutions, as well as the overall planning and implementation, where larger cohorts of students participate in teacher practice simultaneously.

Supportive value for the novice teacher

Integrating the use of reflective practices and mobile devices contributed to the value placed on the use of such a learning approach by novice teachers. Overall, the participants found the use of e-portfolios most valuable, as the following extract confirms:

... it could be useful ... it will help you remember [... ] the next year of what worked well in that class and why ... [all sic].

This demonstrates the possibility of an integrated learning approach that could be sustainable and used in later years. Challis (2005) argues that the mature e-portfolio ought to evolve over time, in terms of the refinement, redevelopment and design, as well as responses to personal growth and feedback. In this regard, one respondent commented:

. and then maybe you encounter a problem and you're completely lost [...] but you'd always ask questions and them maybe someone will come across your blog [. ] and ooh! [. ] I had that problem and this worked for me [. ] open it up to people and you can definitely help each other out [all sic].

Current teacher training programmes can therefore be enriched, and may benefit from this particular learning approach by providing in-service teachers with authentic learning opportunities (Herrington, Parker & Boase-Jelinek, 2014), which could be accessed throughout their teacher careers, creating an online space for current and future collaboration with peers.

Conclusion and Suggestions

Institutional expectations play a significant role in the future success of the use of e-portfolios as potential reflective tools during teacher practice. Requirements regarding the use of mobile devices during lesson observations and class visits, as well as common understanding and implementation of the theoretical underpinnings of an e-portfolio pedagogical approach, serve as the basis for future debates and conversations regarding the appropriateness of such a learning approach in the current teacher training context. Furthermore, the notion of online collaboration (Barrett, 2011) and the development of an online community of practice suggest a reconceptualisation and understanding of what is truly valued during teaching practice, and which ways are most appropriate to achieving such outcomes. Finally, especially within the South African context, the level of digital skills of students can neither be assumed nor ignored. For learning practices aiming to integrate learning technologies to succeed, it remains the responsibility of institutions to provide students with appropriate training, continuous technical support, as well as the design of innovative sustainable learning opportunities for students, whilst participating in teacher practice.

Note

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Anwaruddin SM 2015. Teacher professional learning in online communities: toward existentially reflective practice. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 16(6):806-820. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2015.1095730 [ Links ]

Ash SL & Clayton PH 2009. Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1:25-48. Available at https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/4579/ash-2009-generating.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 28 January 2017. [ Links ]

Barnstable K 2010. 41 benefits of an ePortfolio. Available at http://kbarnstable.wordpress.com/2010/01/08/41-benefits-of-an-eportfolio/. Accessed 21 July 2012. [ Links ]

Barrett HC 2000. Electronic portfolios = multimedia development + portfolio development: The electronic portfolio development process. Available at http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/EPDevProcess.html. Accessed 23 July 2012. [ Links ]

Barrett HC 2011. Balancing the two faces of e-portfolios. In S Hirtz & K Kelly (eds). Education for a digital world: innovations in education (2nd ed). Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Education. Available at http://electronicportfolios.org/balance/balancingarticle2.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2012. [ Links ]

Bolton G 2014. Reflective practice: Writing and professional development (4th ed). London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Boud D, Keogh R & Walker C (eds.) 1985. Reflection: Turning experience into learning. London, UK: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Bourner T 2003. Assessing reflective learning. Education + Training, 45(5):267-272. doi:10.1108/00400910310484321 [ Links ]

Brown C 2012. University students as digital migrants [Special issue]. Language and Literacy, 14(2):41-61. [ Links ]

Candy PC 1995. Developing lifelong learners through undergraduate education. In L Summers (ed). A focus on learning. Proceedings of the 4th Annual Teaching Learning Forum. Perth: Edith Cowan University. Available at http://clt. curtin.edu.au/events/conferences/tlf/tlf1995/candy.html. Accessed 29 January 2017. [ Links ]

Challis D 2005. Towards the mature ePortfolio: Some implications for higher education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3). doi:10.21432/T2MS41 [ Links ]

Clark E & Eynon B 2009. E-portfolios at 2.0-Surveying the field. Peer Review, 11(1):18-23. Available at http://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/e-portfolios-20%E2%80%94surveying-field. Accessed 24 July 2012. [ Links ]

Cohen L, Manion L & Morrison K 2011. Research methods in education (7th ed). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Czerniewicz L & Brown C 2013. The habitus of digital "strangers" in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology (BJET), 44(1):44-53. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01281.x [ Links ]

Denscombe M 2003. The good research guide for small-scale social research projects (2nd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training, Republic of South Africa 2015. National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Revised policy on the minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications. Government Gazette, Vol. 596(No. 38487). 19 February. Pretoria: Government Printers. Available at http://www.dhet.gov.za/Teacher%20Education/National%20Qualifications%20Framework %20Act%2067_2008%20 Revised%20Policy%20for%20Teacher%20Education%20Quilifications.pdf. Accessed 1 February 2017. [ Links ]

De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouché CB & Delport CSL 2005. Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Dewey J 1938. Logic: The theory of inquiry. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Farrell TSC & Mom V 2015. Exploring teacher questions through reflective practice. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 16(6):849-865. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2015.1095734 [ Links ]

Finlay L 2008. Reflecting on 'reflective practice'. Practice-based Professional Leaning Centre (PBPL) Discussion Paper 52. Available at http://www.open.ac.uk/opencetl/sites/www.open.ac.uk.opencetl/files/files/ecms/web-content/Finlay-(2008)-Reflecting-on-reflective-practice-PBPL-paper-52.pdf. Accessed 29 January 2017. [ Links ]

Finlayson A 2015. Reflective practice: has it really changed over time? Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 16(6):717-730. doi:10.1080/14623943.2015.1095723 [ Links ]

Garis JW 2007. e-Portfolios: Concepts, designs, and integration within student affairs. In JW Garis & JC Dalton (eds). e-Portfolios: Emerging opportunities for student affairs: New directions for student services, no. 119. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Garrett N 2011. An e-portfolio design supporting ownership, social learning, and ease of use. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 14(1):187-202. [ Links ]

Gunawardena CN, Hermans MB, Sanchez D, Richmond C, Bohley M & Tuttle R 2009. A theoretical framework for building online communicates of practice with social networking tools. Educational Media International, 46(1):3-16. [ Links ]

Herrington J, Parker J & Boase-Jelinek D 2014. Connected authentic learning: Reflection and intentional learning. Australian Journal of Education, 58(1):23-35. doi:10.1177/0004944113517830 [ Links ]

Housego S & Parker N 2009. Positioning ePortfolios in an integrated curriculum. Education + Training, 51(5/6):408-421. doi:10.1108/00400910910987219 [ Links ]

Jimoyiannis A 2012. Developing a pedagogical framework for the design and the implementation of e-portfolios in educational practice. Themes in Science & Technology Education, 5(1/2):107-132. Available at http://earthlab.uoi.gr/ojs/theste/index.php/theste/article/view/110/77. Accessed 26 January 2017. [ Links ]

Joyes G, Gray L & Hartnell-Young E 2010. Effective practice with e-portfolios: How can the UK experience inform implementation? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(1):15-27. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1099 [ Links ]

Joyes G & Smallwood A 2011. e-Portfolio large-scale implementations - the ePI study. Final report. Nottingham, UK: JISC. Available at https://sites.google.com/site/epistudy/home/final-report. Accessed 13 July 2012. [ Links ]

LaBelle JT & Belknap G 2016. Reflective journaling: fostering dispositional development in preservice teachers. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 17(2):125-142. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2015.1134473 [ Links ]

Lea SJ, Stephenson D & Troy J 2003. Higher education students' attitudes to student-centred learning: Beyond 'educational bulimia'? Studies in Higher Education, 28(3):321-334. doi:10.1080/03075070309293 [ Links ]

Liamputtong P 2011. Focus group methodology: Principles and practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Malthouse R & Roffey-Barentsen J 2013. Reflective practice in education and training (2nd ed). London, UK: Learning Matters. [ Links ]

Meierdirk C 2016. Is reflective practice an essential component of becoming a professional teacher? Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 17(3):369-378. doi:10.1080/14623943.2016.1169169 [ Links ]

Murphy A, Farley H, Lane M, Hafeez-Baig A & Carter B 2014. Mobile learning anytime, anywhere: What are our students doing? Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 18(3):331-345. doi:10.3127/ajis.v18i3.1098 [ Links ]

Ng W 2013. Conceptualising mLearning literacy. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 5(1):1-20. doi:10.4018/jmbl.2013010101 [ Links ]

Parsons M & Stephenson M 2005. Developing reflective practice in student teachers: collaboration and critical partnerships. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 11(1):95-116. [ Links ]

Pelech J 2013. Guide to transforming teaching through self-inquiry. Charlotte, NC: IAP-Information Age Publishing, Inc. [ Links ]

Rabiee F 2004. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63(4):655-660. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004399 [ Links ]

Rhodes B 2016. School visit of secondary teacher students. [Class handout]. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Ritchie J & Spencer L 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A Bryman & RG Burgess (eds). Analysing qualitative data. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Roder J & Brown M 2009. What leading educators say about Web 2.0, PLEs and e-portfolios in the future. In Same places, different spaces. Proceedings ascilite Auckland. Available at http://www.ascilite.org/conferences/auckland09/procs/roder.pdf. Accessed 1 February 2017. [ Links ]

Rodgers M, Runyon D, Starrett D & Von Holzen R 2006. Teaching the 21st century learner. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning, Wisconsin, 1-4 August. [ Links ]

Schon DA 1975. Deutero-learning in organisations: Learning for increased effectiveness. Organizational Dynamics, 4(1):2-16. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(75)90001-7 [ Links ]

Schön DA 1990. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot, UK: Avebury. [ Links ]

Schön DA 1995. Reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Suffolk, UK: Arena. [ Links ]

Sellars M 2014. Reflective practices for teachers. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Steur JM, Jansen EPWA & Hofman WHA 2012. Graduateness: an empirical examination of the formative function of university education. Higher Education, 64(6):861-874. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9533-4 [ Links ]

Tarrant P 2013. Reflective practice and professional development. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Tedla BA 2012. Understanding the importance, impacts and barriers of ICT in teaching and learning in East African countries. International Journal for e-Learning Security (IJeLS), 2(3/4):199-207. Available at http://infonomics-society.ie/wp-content/uploads/ijels/IJELS-Volume-2-Issue-3-4.pdf. Accessed 26 January 2017. [ Links ]