Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.36 n.4 Pretoria Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n4a1302

ARTICLES

Invisible Barriers: The loneliness of school principals at Turkish Elementary Schools

Mithat Korumaz

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey. mkorumaz@yildiz.edu.tr

ABSTRACT

School principals fulfil unique and crucial roles, drawing on their respective experience to react to an increasing number of challenges. They must carry out their roles as school leaders within a context highly charged with emotion. The loneliness of principals at schools urgently requires investigation. Limited details can be found in current academic literature concerning the issue of how principals deal with the issue of loneliness at school. Therefore, the aim of this study is to gain insight into the nature of loneliness among school principals. The study employed a qualitative research design incorporating a phenomenological approach. The participants of the study consisted of seven elementary school principals. The data was collected via face-to-face interviews, and related observations were carried out over the duration of two months during the two semesters of the 2015-2016 academic year. The data was then analysed across three steps, namely an exploration of the general meaning/significance of the data, an encoding of the data, and a subsequent identification of the principal themes involved. As a result of this analysis, three main themes were identified: psychological insight, the organisational climate, and professional effort. Psychological insight is the notion that all participants agreed on and emphasised when asked to offer a definition of loneliness at schools. Participants also agreed on the fact that the organisational climate at Turkish schools represented the most significant reason for principals' loneliness at work. The school principals that participated in the study stated that they invested (additional) professional efforts (in their work) to overcome this invisible barrier. The results were discussed in the light of existing literature, and suggestions were presented within the context of the final discussion.

Keywords: barriers; loneliness at work; school principals; Turkish elementary schools

Introduction

School leadership has assumed a unique priority in the process of education policy process when considered from an international perspective (Dimopoulos, Dalkavouki & Koulaidis, 2015), with the emergence of new types of schools that constitute open and socially complex adaptive organisations, which represent the driving force of emerging economies (Keshavarz, Nutbeam, Rowling & Khavarpour, 2010). Such schools have brought forth new kinds of responsibilities and challenges for school leaders. Therefore, it is possible to state that the changing nature of the pivotal role played by the principals in these new schools involves the development of a positive and enabling environment, the enhancement of motivation among teachers, staff with regard to professional development, the creation and fostering of a positive school climate (Robinson, 2007), and so on. As usual, the extent of these changes has led to new challenges for these leaders. One of the greatest challenges is simply to keep up with and manage the continuous changes with which they are faced. The challenges that have emerged in the school environment have led to new requirements on the part of principals, such as their need to encourage long-term intrinsic motivation among teachers, a willingness on their part to support the professional development of their staff, and the need for increased emotional competencies to exercise their duties. One of the most noticeable challenges for principals may be the need to heighten emotional competencies as they face the challenges of their position (Howard & Mallory, 2008).

School principals are expected to act as the "leaders" of teachers, support staff and students at their schools. Therefore, they are trained to set an example as to what constitutes 'correct' behaviour, nature and character, and to be sensitive to the diverse needs of all of the people who are obliged professionally to respect their authority, both within and beyond the school setting (Howard & Mallory, 2008). They are not rule makers; for instance, Popper (2011:29) emphasises the fact that "a great difference has already been highlighted between the concept of 'rulership' that includes compelling the obedience of other people through the exercise of fear and an alternative style of leadership that consists of people following the leader that is based on principles of trust and enthusiasm". They possess a unique personality; however, they also share some common characteristics of leadership (Goffee & Jones, 2004). Leadership in this context is defined as having an influence on people for the purpose of organisational goals, the motivation of staff to reach these goals, and the coordination of the pursuit and achievement of these objectives (Rokach, 2014).

In this age of increased managerial accountability, principals' leadership roles have evolved in light of the new administrative responsibilities that have been placed on school leaders. These responsibilities added to the principal's goals as the head teacher; namely to assist students to adapt to the needs of wider society, and to support their pupils towards academic achievement (Sergiovanni, 2005). Rokach (2014:48) views the school principal as "a 'gatekeeper' responsible for coordinating events and relationships outside [school], inside [in school], and who assumes the position of a position, standing on the threshold between the two". Rokach (2014) further discusses that school principals are expected to assume complete responsibility for the administrative and instructional procedures at the school.

Those responsibilities are highly demanding and bring educational leaders into conflict with their staff, organisation, and the community. In addition, Howard and Mallory (2008:7) argue that "school leaders today are charged with fulfilling exacting curriculum standards, educating an increasingly diverse student population, shouldering responsibilities that once belonged in the home or the community; they also face the threat of termination of their employment if their schools do not record instant results." It is therefore not surprising that there exists a chronic shortage of principals in our schools. Such responsibilities combined with the nature of leadership bring loneliness and isolation to life 'at the top', which is not a crowded place (Rokach, 2014). Naicker and Mestry (2015) claimed that principals do not work in collaboration (with staff), but in isolation. A number of studies investigating the emotional lives of leaders have shown that 52% of Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) frequently felt lonely (Bell, Roloff, Van Camp & Karol, 1990; Gumpert & Boyd, 1984), and that leaders on average feel lonelier than their employees (Bell, 1985; Hojat, 1982); while in school settings, the loneliness of principals affects their job satisfaction (Dussault & Barnett, 1996; Dussault & Thibodeau, 1997; §is.man & Turan, 2004). The degree of loneliness varies in severity; it is shaped by the working environment, and involves factors such as the arrangement of positions within the organisational hierarchy (Wright, 2012). In other words, climbing the professional ladder means an ascent to a ' summit of loneliness' . As a result, school leaders or principals may make many of their key decisions in a state of extreme loneliness (Stephenson, 2009).

Loneliness

A large number of studies have been conducted on various aspects of the phenomenon of loneliness. However, there is still no single definition of the term. Loneliness, isolation, alienation or a lack of social support are concepts that are often confused with that of loneliness. However, the concept of loneliness as distinct from other concepts, is dependent on the philosophy on which it is based, which also incorporates subjective feelings. Freda Fromm-Reichman investigated both the reasons and outcomes for loneliness as a psychological phenomenon (Bullard, 1959). Moreover, Mousta-kas (1961) and Rogers (1970) defined loneliness from an existentialist perspective, as those forms of imagination that are given structure by individuals. Weiss (1973) underlines loneliness as a lack of emotional satisfaction with social relations as they manifest themselves in reality. Arriving at a satisfactory definition of loneliness has always been a hard task, because it requires strong correlations between individual, organisational and social variables within a specific time and context. One of the most commonly accepted definitions of loneliness is the difference between desired and actual relations (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Ernst and Caciop-po (1999) define loneliness as a subjective feeling, resulting from poor communication and a lower level of social interaction with others than those that were (at first) anticipated. There is no opposite definition or antonym of loneliness. When loneliness disappears, normality appears in the form of a manifestation such as hunger, thirst or a sense of being in pain (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008).

Wright (2005) collects the theories on which loneliness depends under four basic topics, where early theories related to the study of loneliness have been examined from two main perspectives, one of which is the psychoanalytic or post-Freudian perspective. Wright further purports that loneliness emanates from narcissism and hostility at a younger age, unfulfilled infantile needs for intimacy, or lack of early attachment figures (Weiss, 1973). The other perspective is that of humanism or existentialism, which defines loneliness as a form of anxiety. The main question posed from the cognitive processes perspective is whether the cognitive expectation of desired relationships is satisfied or not (Archibald, Bartholomew & Marx, 1995). This perception of discrepancy is related to that of abandonment and lack of attachment. An absence of social networks is another determinant of loneliness (Fisher, 1994). The difference between desired and actual relations addresses loneliness, but in fact, this can only be true in theory. One does not feel lonely only if one perceives loneliness at a profound level. When considered from social and behavioural perspectives, social skills are regarded as the main determinants of the quality of social interaction (De Jong-Gierveld & Kamphuls, 1985). Positive behavioural qualities of social interactions decrease perceived loneliness (Wright, 2005). On the other hand, negative behavioural qualities involved in social interactions increase susceptibility to loneliness and terminate with causes and effects of loneliness, which might in fact be one in the same (Killeen, 1998). According to Horowitz, French and Anderson (1982), loneliness begins with "thoughts" of isolation and separation from the cognitions of others. In the second phase, this triggers certain negative "emotions" such as anger, despair and fear. The last step of loneliness is the provocation of undesired "behaviours" such as the avoiding of social interaction and participation in social networks. The social and emotional loneliness perspective is based on Weiss' (1973) classification of the phenomenon as 'emotional loneliness' (the absence of a personal, intimate relationship or interaction) and 'social loneliness' (a lack of social "connectedness", the absence of a sense of community or feeling/existing outside social networks) (DiTommaso & Spinner, 1997; Russell, Cutrona, Rose & Yurko, 1984; Stroebe, Stroebe, Abakoumkin & Schut, 1996).

The negative psychological impact of loneliness has been researched extensively. However, the issue of loneliness at work remains under-investigated. There are a number of pieces of evidence and reasons to assume that loneliness might be more visible within a work setting than in a personal life context (Dussault & Thibodeau, 1997; Lam & Lau, 2012; Reinking & Bell, 1991). In this regard, Spillane and Lee (2013:3) argued that "school principals often struggle with feelings of professional isolation and loneliness as they transition into a role that carries ultimate responsibility and decision-making powers." Frequently, those principals, on assuming their position, also have difficulty dealing with the legacy, practice, and style of the previous principal (Duke, 1987; Hart, 1993). School principals are expected to satisfy both the structural and strategic needs of the organisation. For example, Rokach (2014) indicated that school leaders need the social support of employees, and that in cases where they do not receive this support, they may experience loneliness (Mercer, 1996). Lam and Lau (2012) have asserted that school principals experiencing loneliness, will have lower quality leader-member and organisation-member exchanges at work and they will be less effective both in the roles directly connected to their job description, and with the additional, non-prescribed roles that they execute in their workplaces. In addition, cultural contexts shape the correlation between leadership and loneliness. "Countries with western, more individualistic values, utilize [sic] management practices that focus on facilitating skill-based (working) lifestyles, as well as providing the tools that employees need" (Rokach, 2014:52). On the other hand, Şişman and Turan (2004) showed that the collectivist values of Turkish society influence school principals' needs for socialisation so they may experience certain degrees of social-emotional loneliness. Contrasting his research with studies previously conducted on the topic, Sarpkaya (2014) discovered that school principals in Turkey felt a deeper level of loneliness from a social rather than an emotional perspective. Yilmaz and Altinok (2009) revealed that Turkish school principals' levels of loneliness are quite low. In the same year Izgar (2009) reported that school principals' loneliness was moderate in Turkey, while Oguz and Kalkan (2014) found that school principals experienced low levels of loneliness at schools.

The aforementioned studies have all presented contradictory results with respect to the loneliness of school principals in Turkey; these studies have all tried to determine the "level" of the loneliness of principals at work using quantitative designs. The fundamental difference among them is that Izgar (2009), Şişman and Turan (2004) and Yilmaz and Altinok (2009) used the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) loneliness scale, which was developed to determine the loneliness level of participants in social contexts, but that did not focus particularly on the loneliness that the same participants experienced at work. In contrast, Bakioglu and Korumaz (2014), Oguz and Kalkan (2014) and Sarpkaya (2014), tried to assess loneliness at work using the Loneliness at Work Scale. All of these studies, which tried to determine the level of loneliness in sub-dimensions, generated beneficial results that certainly help the observer to understand the loneliness of principals in a Turkish context. However, they may all be considered insufficient in revealing the underlying reasons for loneliness among principals at school, the meaning of loneliness according to principals, and the issues and incidents that principals experienced. They also did not sufficiently account for how principals overcome loneliness at school within a Turkish school setting, in which principals are appointed from among teachers and are rendered responsible for all administrative process. At the same time, there have been limited studies conducted corroborate qualitative research that describes the loneliness of school principals in Turkey. In this context, the purpose of this study is to determine the perceptions of loneliness among school principals at Turkish schools.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative research design incorporating a phenomenological approach, to describe the perceptions of school principals with regard to loneliness at Turkish elementary schools. Phenomenological research is a qualitative method that aims to determine the whole issue or phenomenon under discussion (Patton, 2002) and to highlight the essential meanings of human experiences (Lin, 2013). According to Smith (2011:2), "phenomenology studies are organized [sic] according to conscious experiences from the first person point of view, along with presentation of the relevant conditions of experience", and defines it as such. Creswell (2007:57) further described a pheno-menological study as one that "describes the meaning for several individuals of their lived (or shared) experiences or a phenomenon". This phenomenological study allows for the exploration of the experiences of elementary school principals concerning loneliness in a school context (Berg & Lune, 2012; Creswell, 2007; Kaya & Aydin, 2016; Stake, 2010). Qualitative research, which compiles interpretive activities, privileges no single methodological practice over another, but rather stresses qualitative research methods and strategies such as phenomenology to reveal the truth of a phenomenon (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). This phenomenological study that "describes the meanings of loneliness for several individuals of their lived experiences as a concept or a phenomenon" (Creswell, 2007:57-58), is used to investigate how an individual makes sense of an experience. In a phenomenological study, understanding regarding the phenomenon is elicited, and insight is gained by interviewing knowledgeable participants (Yin, 2012). Specifically, this study sought to explore the lived experiences of elementary school principals' concerning loneliness within a school setting.

Participants

Participants were selected based on their lived experiences concerning the phenomenon of loneliness and their willingness to share knowledge regarding their loneliness within the school setting, so that it might serve as an appropriate contribution to the purposeful sampling method. The participants of the study, all of whom were elementary school principals, were determined according to criterion sampling that represents one of the most common types of purposeful sampling. Patton remarks that "criterion sampling means to review and study all cases that meet certain predetermined criteria of importance" (2002:238). The researchers' choice concerning the sampling type was based on the understanding that "criterion sampling works well when all individuals studied represent people who have experienced the same phenomenon" (Creswell, 2007:128).

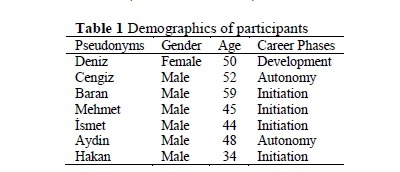

Particular settings, individuals and events can be selected deliberately in order to provide information with the view to answering specific research questions (Maxwell, 2009). The criteria of the study were gender, age and career phases. Participants of this study were seven (n = 7) principals working at elementary schools in Istanbul, Turkey. The age of participants varied from 34 to 59. We used Bakioglu's (1994) classification of school principals' career phases. Hereunder, the Initiation Phase contains from 1 to 4 years of experience and a high need of professional development. The Development Phase refers from 4 to 8 years of experience and high career chance. Autonomy is the third phase and refers from 8 to 12 years of experience. Autonomy phase principals are expected to decide autonomously. Four of the participants were at the initiation phase, two of them were at the autonomy phase and one of them was at the development phase of their career. One of the participants was female and six of them were males.

Settings and Procedures

In March, 2015, school principals from several elementary schools in Istanbul were invited via school e-mail to participate in the study. Over 80 elementary school principals were contacted; sixteen principals responded via email and were accepted to participate in this study. Their personal details was obtained in a follow-up e-mail requesting more background information from the principals and responding to the specific questions they raised about the study. Seven of sixteen principals were selected according to the criteria of the study. Unfortunately, only one of the participants was female. This limited researchers in their ability to find the differences in feelings of loneliness according to gender.

Contact information and schedules of availability were obtained from the principals in order to best determine the time and location for the first interview meeting. The principals provided their home and school contact information. Between April 07 and May 30, 2015 school principals gathered for individual interviews that were conducted by researchers. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed for each initial meeting. Field notes were also taken to reinforce the key points of the participants.

Research Questions

The qualitative phenomenological research question guiding the study was: What are the perceptions of schools principals at Turkish elementary schools concerning loneliness. In developing the themes, the researchers constantly referred to the several sub-research questions guiding the study that were determined as follows:

1. How do Turkish school principals define loneliness?

2. Why do school principals feel loneliness at school and what are the individual and organisational causes?

3. How do school principals overcome loneliness at school?

4. What are the organisational and individual outcomes of school principals' loneliness?

Data Collection and Analysis

Prior to beginning the study, an application was made to the university Institutional Review Board (IRB) for research involving human subjects. Permission was obtained from the IRB at Yildiz Technical University to conduct this study, and was issued on March 19, 2015. Participants were asked to sign the consent form, and were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary. The participants were also notified that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that their responses were confidential. Pseudonyms were used to protect participants' identities and ensure confidentiality.

The data collection process was based on a triangulation method using three different data-collection methods, viz. face-to-face semi-structured interviews, observations and field notes. The use of multiple methods to gather data leads to the triangulation of data to support the attempts of researchers to produce more accurate results (Den-zin & Lincoln, 2011). The study data was gathered during the spring academic term of 2015. Both the individual and focus group interviews consisted of open-ended and seven in-depth questions about the principals' perceptions and lived-experiences with regard to loneliness. We used focus group interviews "to learn through discussion about conscious, semiconscious, and unconscious psychological and sociocultural characteristics and processes among group members" (Berg & Lune, 2012:111).

The interview protocol was revised by five experts in the field of educational Leadership and Curriculum and Instruction Departments. The questions in the interview serve to open further discussion about principals' perceptions and experiences concerning loneliness. To ensure the reliability and validity of the interview questions, first of all, five experts' opinions were considered, and the questions were revised accordingly. These questions were applied to two participants as a pilot study, and the questions were finalised before the actual interviews took place.

The interviews lasted approximately 40-60 minutes, where each interview was audio-taped. The interview process took place at the schools where the principals were employed. The participants were informed about the research process and assured that the information they gave would remain confidential. The principals were first given a copy of the research narrative that outlined the specific purposes and expectations of the study. They were also asked to read and sign the information sheet, and were given a copy of the form for their personal records.

Three of the principals were observed separately on two different working days. The purpose of the observation of the participant was to witness and understand the phenomenon in depth in its natural setting (Berg & Lune, 2012; Patton, 2002). Before the observation, an observation checklist form was developed. During the observation, notes were also taken and collected after each of the observations. Data was collected by checklists and field notes taken during observations supported the information gathered during the interviews.

After the interviews, the audio recordings and observation field notes were transcribed. The transcriptions were reread several times and then classified accordingly to identify the themes. The codification and analysis of data were conducted manually by the researchers. For purposes of analysis, the steps of (1) exploring the general sense of data; (2) (en)coding the data (Saldana, 2009); and (3) specifying the themes, were followed (Creswell, 2012).

Transcripts of the interviews and field notes from the observation were examined by different experts; these multiple examinations contributed to the reliability of the analysis. Research reports, compiled using the analysis and interpretations of the data obtained were prepared. and returned to the research participants for "member checks" to establish credibility, reliability and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Maxwell, 2009; Streubert & Carpenter, 1999), and to assess and strengthen the accuracy of the data (Creswell, 2007). This process resulted in three overarching themes, which include: psychological insight, organisational climate, and professional efforts.

Findings

The analysis of the transcribed forms of individual interviews, focus group interview and observations indicate that psychological insight is the most emphasised notion that all participants agreed on with respect to the definition of loneliness at schools. Participants also shared the view that the organisational climate of Turkish schools represented the most significant reason for principals' loneliness at work. Participant school principals stated that they exerted/made professional efforts to overcome the invisible barrier. "Feeling like a sheep dog among a flock of sheep", "an invisible curtain" and "a captain controlling the rudder alone", were culturally-specific metaphors voiced during the interviews that helped in providing definitions of the types of loneliness experienced by principals. In brief, the following themes were identified: psychological insight, organisational climate and professional effort.

Theme One: Psychological Insight Analysis of the transcriptions obtained during the application phase of the research reveals that the expression 'psychological insight' was repeated by all participants, and the most commonly used description, where all participants emphasised the notion of psychological insight. For example, one school principal defined loneliness at the school as follows:

Loneliness at school is a kind of psychological deprivation, because there are teachers, students and parents around me; however, I still think I am isolated in my feelings. I feel really alone (April, 2015, Male, 59).

Another principal emphasised the definition of loneliness at work in the capacity of school management. Again, he employed the notion of psychological insight:

I can define loneliness as a subjective feeling. All of the principals in Turkey work in the same conditions, but some feel lonely, while others do not. I neglect myself while doing my daily routines. That makes me antisocial (August, 2015, Male, 44).

Three of the participants preferred to use culturally specific metaphors that explain the feeling of loneliness experienced by principals at the school. For example, one of the participants defined his loneliness at the school as "an invisible curtain" between him and other individuals at the school:

I think the most important factor that contributes to being lonely at the school is unsatisfactory communication... I try to eliminate barriers to bring about stronger communication. Unfortunately, there is an invisible curtain between me and others at the school (September, 2015, Male, 48).

Another participant preferred to define loneliness at the school "feeling like a sheepdog among a flock of sheep". He emphasised the protectiveness of the school leaders in administration both for teachers and students:

Everyone at the school I have contact with regards me as someone who will confirm or reject their plans or suggestions. I think [only] a few people value me because I am a human. I can define loneliness at the school as feeling like a sheep dog in a flock of sheep. I try to protect them every time or serve them, but they remain distant from me (August, 2015, Male, 52).

The participants also mentioned the factor of psychological insight as featuring on the list of descriptions that can be used to punish newly-appointed principals. For instance, one of them expressed his opinion as follows:

Being lonely at the school is a subjective feeling for anyone. I can easily state that if a principal has newly arrived at a school, that means he/she will pay the price for the position. He/she will be isolated, ostracised, or alienated by others. It is a kind of punishment (August, 2015, Male, 45).

Similarly, one of the participants defined loneliness as a lack of closeness that can be regarded as a sub-theme of psychological insight. He stated his thoughts as follows:

At first glance, no-one can say that a school principal feels lonely. But indeed, we can experience loneliness more deeply than others. To me, loneliness means a lack of close friends in whom I can confide about my private life (September, 2015, Male, 34).

A general analysis of the answers provided by the participants revealed that the notion of psychological insight was stressed and that there was a consensus regarding the definition of the loneliness of principals at the school.

Theme Two: Organizational Climate Analysis of the data obtained during the application phase of the research reveals that organisational climate was also used by the participants, and it was one of the most frequently repeated notions.

All of the participants emphasised the notion of organisational climate to be the most important reason for the loneliness of principals. As well as unplanned and heavy workloads, intolerance to differences and hierarchy were the sub-themes of this notion. Some definitions of organisational climate were specified as follows:

Both teachers and principals are willing to collaborate in the Turkish school culture. They want to work individually at the school. The educational system encourages working alone because the main goal is to focus on academic competition and the achievement of the students. That encourages principals to work and become lonely at school (August, 2015, Male, 59).

***

Principals are the only ones responsible for decisions. Each and every decision that is not shared with others in the school creates two groups: the satisfied and the unsatisfied. The teachers, students or parents who are unsatisfied with my decisions sometimes keep me at a distance. But it is a kind of necessity for me. The educational system only allows me to take initiative for making decisions at the school (September, 2015, Male, 48).

Most of the participants mentioned that the excessive workload of principals made them feel isolated at the school. For instance, one participant emphasised the amount of unplanned work and that the lack of set time limits his work, incarcerating him in his office. He also brought up bureaucratic processes as representing time-consuming duties as part of the administration process. He clarified his argument as follows:

The most important reason preventing me from connecting with teachers, students or parents are issues of time. I have to get through lots of work in the same day. Nobody would think that these bureaucratic processes take such a long time. I really feel responsible for getting this work done (August, 2015, Male, 59).

With regards to this viewpoint, it was observed that the principals had to spend most of their time involved in bureaucratic routines, within the confines of their offices at their schools. Their contact time with others at the school was limited. They seemed to suffer emotional deprivation because of loneliness. Another participant mentioned excessive workloads that differed from those of other ' ordinary' principals. He expressed his thoughts as follows:

I have observed that prominent principals are the only ones who are defined as successful. Therefore, I never want to be an 'ordinary' principal at my school. All of these efforts to be an extraordinary principal bring me additional responsibilities and an increased workload. When I accomplish these tasks, I realise that I am isolated and lonely in my room (September, 2015, Male, 34).

Another sub-theme of the organisational climate of the school is intolerance to differences. One participant, who came from a culturally-different background to that of the other participants, found people to be intolerant of others' differences at the school. He asserted that intolerance of others was one of the most significant factors that led to the loneliness of principals at the school. He reflected his thoughts as follows:

Principals, teachers, vice-principals, parents or even students are too intolerant towards each other. Particularly during recent years, we don't want to work or be together with people who are different than us. I can list these differences as religion, ethnic diversity, political point of view, mother tongue, or even our home towns. The political influences exerted on schools have separated teachers and principals. I think this separation has an extraordinary effect, in that it makes people feel unhappy and alone at the schools (August, 2015, Male, 59).

Similarly, the only female participant of the study identified that the gender of the principal was a significant variable that prevented close interaction with teachers, vice-principals, and even parents. In other words, she meant that males in the school keep her at arm' s length, because of the gender difference. She expressed her thoughts clearly as follows:

At the beginning of my career, I thought that gender was not such a crucial aspect of the administrative process. But now, I think that the gender of the principal is very important in some cases. As you know, most of the principals in Turkey are male, so patterns of behaviours or expected behaviours are generally masculine. Whenever I try to behave like a man, teachers find me 'artificial'. On the other hand, when I try to be who I am, they then find my behaviour too ' feminine' to manage a school. It is a kind of administrative dilemma. Moreover, teachers or others in the school avoid becoming my close friend. As a female principal, I need to learn how to work alone. I am not sure whether this is cultural thing or not (July, 2015, Female, 50).

As a source of loneliness, intolerance consists of the political views of teachers' unions at the present time. One of the participants thought that differences in the political views of teachers because of their union membership separated them from each other, and led to the emergence of political subgroups in the school. He stated his opinions as follows:

In addition to the excessive workload, differences in the political views of teachers because of their union membership have led to their separation. When I began to work at this school as a principal, I was alienated by teachers who were members of another teachers' union. These kinds of barriers are too strong to overcome (August, 2015, Male, 52).

Some of the participants pointed out that the hierarchical structure (of schools) prevents principals from joining a (social) group in the school or having close relationships. The concept of hierarchy involves the erecting of communication barriers created by teachers who regard the principals as agents of the status quo. For instance, one of the participants of the study regarded himself as a gatekeeper of the school in the first year of his career phase as a principal; he thought that this kind of his behaviour reflected a hierarchical perspective. He stated his opinions as follows:

In the first years of my job, I tried to balance my relations according to the formal process. It might be a kind of (natural) instinct to protect my school. But after some years of experience, I realised that this made me feel alone (August, 2015, Male, 44).

At the same time, it was noted in observation that most of the teachers and vice-principals tended to behave towards the principal as if he were the only one who held responsibility for the operation of the whole school. This attitude occurred as a result of the organisational climate that created an invisible gap between the principal and all others at the school.

Similarly, one participant expressed his hesitation to accept the views (articulated by teachers) of his being regarded as an agent of the status quo as follows:

As a principal, I am the only one responsible for everything in the school. Therefore, I try to control everything. But teachers regard me as a ' controller' or ' agent' of the system. They adjust their relationship according to this outlook (September, 2015, Male, 48).

When the participants' statements are analysed in general, it is revealed that the notion of organisational climate was emphasised quite often by participants, and that this culture created loneliness for the principals, or even strengthened its effects.

Theme Three: Professional Efforts An analysis of the findings obtained during the application phase of the research reveals that the phrase "professional efforts" was also a regularly repeated notion by most of the participants. This notion includes the manner in which the principals try to overcome loneliness at school. All seven participants emphasised this notion. Five of the participants' professional efforts focused on planning a variety of activities and events for everyone at the school with the aim of minimising loneliness. The professional efforts of the other two participants focused on getting closer to their inner circle. For instance, one of the participants' expressed his practice of using cultural codes to overcome loneliness. He stated his opinions as follows:

When I feel really lonely, I try to solve this problem over a long period of time. If it becomes an unsolvable problem, I would try to use the cultural codes of the people. These codes tell me "stay close to your friends, people of this culture will be effected by these codes and feel much closer" (August, 2015, Male, 44).

The notion that principals try to use their professional efforts to overcome loneliness is widely shared. This included visits to parents to maintain and revitalise the relationship between principals, students and parents. One participant expressed his opinions in the same way:

When I feel lonely in my room, I try to organise an event that parents and (all) students can attend. In addition, we visit students and their parents in their homes at least two times a year. Thus, I strengthen my relationship with parents and my students. I feel less lonely, in particular when I spend time with my students (August, 2015, Male, 52).

This participant was observed preparing breakfast for teachers who came to school early in the morning. Similarly, one of the participants emphasised the importance of knowing and being known by others. His efforts seemed to focus on becoming familiar with the others in the school. He expressed his opinions as follows:

I realised the more teachers, students and parents know about me, the closer they feel. And actually when this happens, I feel closer (to them) as well. Becoming familiar with them has decreased my loneliness to some extent. Now I convert my efforts to get to know each of the students more closely. I think that I will feel less lonely when I get to know my teachers and students more closely (September, 2015, Male, 34).

Another effort of the principals was to concentrate on the relationship with the parents. This notion was expressed as "finding satisfaction in (one's) family" by one participant, who defined herself as being committed to her family. She stated her thoughts as follows:

Loneliness at the school is not a feeling that I can overcome (everything) by myself. I take shelter behind my family in such cases. The only thing that satisfies me is my husband and my son. I try to spend time with them and expect their love. They can make my day (July, 2015, Female, 50).

Another participant with sufficient (extensive) experience in school management emphasised the need to make plans to banish loneliness at work. He stated his thoughts as follows:

In our school there are more than one thousand students, 30 teachers, three vice principals, three officers and four cleaners. That means that theoretically, I can be in contact with more than one thousand people every day... But in practice, I have to stay in my room for routine assignments. That makes me unhappy and lonely. Some years ago I decided to make myself more present in corridors and in the teachers' room. My first plan to rid myself of loneliness was to spend more time among school members (August, 2015, Male, 59).

It was also noted in observations that principals tried to implement plans to overcome loneliness at the school. The teacher mentioned above tried to be visible in corridors and teachers' rooms at every possible time. Similarly, another participant expressed that he saw celebrations and important days in the school calendar as opportunities to overcome loneliness at school. He gave his opinions as follows:

I try to make plans to meet everyone on celebrations and important days. To gather everyone together for a celebration is not an easy job. But I think these days and celebrations are key opportunities to develop strong relations. In particular, we meet for dinner during Ramadan (annual month of Muslim fasting and religious activities). I can say that I try to do something planned. These really work (September, 2015, Male, 48).

A general analysis of the answers revealed that professional efforts were very important in establishing close relations and reducing loneliness at the school. Most of the participants emphasised that they try to overcome loneliness through the planning and holding of school events. That can be interpreted as the principals' implementation of plans to facilitate socialisation so as to prevent loneliness at work.

Discussion and Conclusion

Analysis of the principals' opinions on loneliness and interpretations of the findings are expected to contribute to a wider understanding of how school principals experience loneliness, the reasons for this phenomenon, and the efforts that principals make to overcome this undesirable feeling. The analysis of the findings of this study revealed that principals mostly agree on the definition, the reason and the methods they use to overcome loneliness. Principals preferred to define loneliness as a psychological insight. They also asserted that the most common reason for loneliness was the organisational climate of Turkish schools, most notably the fact that principals are appointed from among teachers, and are seen as the only ones responsible for all of the administrative processes of the institutions. It was also discovered that principals are reluctant to overcome loneliness at the school through their professional efforts.

The study's findings showed that loneliness at work was defined as a form of psychological insight by school principals. Both early and current definitions of loneliness by other researchers similarly focus on the psychological aspect of this feeling. Ernst and Cacioppo (1999) stated that loneliness was to be regarded as a subjective feeling, resulting from poor communication and a lower level of social interaction. The findings of Stephenson's study (2009) focused on the psychological side of the loneliness, as resonant with findings that could be deduced from the principals' expressions in the current study. Another well-known definition of loneliness incorporates clear stages; it begins with "thoughts" of isolation and separation from others (Horowitz et al., 1982). Similarly, Wright (2005) and Wright, Burt and Strongman (2006) defined loneliness particularly in terms of the emotional and social aspects of the workplace. Hawkley, Thisted, Masi and Cacioppo (2010) emphasised that loneliness was a serious problem, related to certain psychological problems. In this study, in keeping with the findings of the literature and definitions of loneliness, the most commonly mentioned notion by school leaders was psychological insight, which served to define the meaning of loneliness.

The notion of organisational climate was also the most frequently reiterated by the participants. Similarly, there are many studies that mention the influence of organisational climate on the feelings of loneliness experienced by principals. For instance, Howard and Mallory (2008) discovered that leaders feel a deeper sense of loneliness than do employees, because of organisational variables. Moreover, Rokach (2014) indicated that school leaders need the social support of employees; in cases where they do not receive this support, they might experience loneliness in the workplace. For instance, lonely principals may receive poorer organisational support. Lonely principals need more satisfactory relations, since their socio-emotional needs of affiliation may be ignored at the school (Lam & Lau, 2012). Wright (2012) stated that loneliness in the workplace may be correlated with the isolation of leaders regarding the responsibilities they assume, and the decisions about others they are compelled to make. Studies within the Turkish school context have produced similar results. For instance, Tabancali and Korumaz (2015) revealed that leaders in educational settings in Turkey experience loneliness significantly more than teachers or other staff as a result of organisational climate and culture. Campbell, Forge and Taylor (2006) indicated that principals experienced loneliness in the first phases of their careers, because they had not yet become fully familiar with the organisational climate of the system. Similarly, in this study, the participants stated that school principals experienced feelings of loneliness at work as a result of the organisational climate, such as a lack of planning, excessive workloads, or intolerance to differences and hierarchy.

Professional effort was yet another notion that was often emphasised in this study. This especially showed how school principals try to overcome loneliness at the school. Heystek (2015) stated that every effort could be motivational when it met the needs of the person. Yahyaoglu (2005) suggested that leaders feel loneliness to a deeper extent than do others, and that this was an undesirable situation for them. Consequently, they attempted to discover alternative approaches to overcoming it. Loneliness is a negative feeling that needs to be eradicated immediately by leaders. The degree of loneliness varies, and is shaped by issues related to the work environment such as the position in the organisational hierarchy (Wright, 2012). Herlihy and Herlihy (1980:8) clearly expressed that:

When principals look to the mechanisms available for coping with stress-fight or -flight, they are caught in a double bind. While they might prefer to 'fight' to act to assuage their loneliness by discussing their problems with others, they perceive this mechanism as being unavailable to them. Thus, the majorities choose ' flight' and eventually leave the principalship. This is both unfortunate and unnecessary; means do exist for coping with the loneliness of the principalship'. According to Aronson (2001), leaders possess certain ability to solve problems, to exhibit self-control and self-regulation, and to make professional effort. In this study, results were produced that were similar to the findings in the literature, namely that the participants mentioned that school principals initiated professional efforts to overcome loneliness at school. Furthermore, Naicker and Mestry (2015) claim more collegial working relations between principals ought to be pursued. The efforts of the principals tended to encompass an attempt to seek affiliation and identification with the organisations at which they were employed (Meyer, 2009). This is because every respective principal may develop an emotional attachment to his or her own organisation; loneliness therefore constitutes an invisible barrier to this attachment.

As most of the scholars and researchers emphasised, school principals are crucial elements in the successful operation of the school. Rokach (2014) viewed the school principal as a 'gatekeeper' , and he further discussed that school principals were supposed to assume all the responsibilities for administrative and instructional procedures at the school. It was therefore possible to say that the psychological experiences they undergo may influence the whole organisation. Loneliness, as the phenomenon under discussion of the current study, might be regarded as one of the most important aspects of the principals' psychological experiences. The psychological aspect of this loneliness indicates that longitudinal studies are needed to reveal the in-depth findings about the loneliness of principals. At the same time, the number of studies concerning the loneliness of principals conducted in Turkey is limited, we therefore recommend that longitudinal studies be conducted regarding school principals' loneliness. On the other hand, only 12% of school principals in Turkey are female. Therefore, the fact that just one female principal volunteered to participate in this study was not a surprise. This can be taken as one of the limitations of this study. Further research ought to focus on the loneliness of the female principals specifically. Finally, policy makers should concentrate on designing in-service training programmes for school principals in schools so as to help them to cope with the loneliness within an educational context.

Note

i Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Archibald FS, Bartholomew K & Marx R 1995. Loneliness in early adolescence: A test of the cognitive discrepancy model of loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(3):296-301. doi: 10.1177/0146167295213010 [ Links ]

Aronson E 2001. Integrating leadership styles and ethical perspectives. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 18(4):244-256. doi:10.1111/j.1936-4490.2001.tb00260.x [ Links ]

Bakioglu A 1994. Okul yöneticisinin kariyer basamaklari: Íngiliz egitimi sisteminde yöneticilerin etkinlikleri üzerindeki faktörler [Career phases of school principals: The factors on principals in education system of England]. Marmara Egitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 6(6):17-28. Available at http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/35094707/OKUL_YONETICISININ _KARIYER_ BASAMAKLARI_INGILIZ_EGITIM I_SISTEMINDE_YONETICILERIN_ETKINLIKLERI_UZERINDEKI_FAKTORLER_1.pdf? AWSAccessKeyId= AKIAJ56TQJRTWSMTNPEA&Ex pires=147881 4006&Signature=rySQXxR37FEeWlGUlGosaf8BmZc%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DOkul_Yoneticisinin_Kariyer_Basamaklari_I.pdf. Accessed 10 November 2016. [ Links ]

Bakioglu A & Korumaz M 2014. Investigation of teachers' loneliness at school according to their career phases. Marmara Egitim Bilimleri Dergisi [Journal of Educational Sciences], 39(39):25-54. [ Links ]

Bell RA 1985. Conversational involvement of loneliness. Communication Monographs, 52(3):218-235. doi:10.1080/03637758509376107 [ Links ]

Bell RA, Roloff ME, Van Camp K & Karol SH 1990. Is it lonely at the top?: Career success and personal relationships. Journal of Communication, 40(1):9-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02247.x [ Links ]

Berg BL & Lune H 2012. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (8th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Bullard DM (ed.) 1959. Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy: Selected papers of Frieda Fromm-Reichman. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Cacioppo JT & Patrick W 2008. Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Ltd. [ Links ]

Campbell KT, Forge E & Taylor L 2006. The effects of principal centers on professional isolation of school principals. School Leadership Review, 2(1):1-15. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2007. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

De Jong-Gierveld J & Kamphuls F 1985. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9(3):289-299. doi: 10.1177/014662168500900307 [ Links ]

Denzin NK & Lincoln YS 2011. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Dimopoulos K, Dalkavouki K & Koulaidis V 2015. Job realities of primary school principals in Greece: similarities and variations in a highly centralized system. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice, 18(2):197-224. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2014.954627 [ Links ]

DiTommaso E & Spinner B 1997. Social and emotional loneliness: A re-examination of weiss' typology of loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(3):417-427. doi: 10.1016/S01918869(96)00204-8 [ Links ]

Duke DL 1987. School leadership and instructional improvement. New York, NY: Random House. [ Links ]

Dussault M & Barnett BG 1996. Peer-assisted leadership: reducing educational managers' professional isolation. Journal of Educational Administration, 34(3):5-14. doi:10.1108/09578239610118848 [ Links ]

Dussault M & Thibodeau S 1997. Professional isolation and performance at work of school principals. Journal of School Leadership, 7(5):521-536. [ Links ]

Ernst JM & Cacioppo JT 1999. Lonely hearts: Psychological perspectives on loneliness. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8(1):1-22. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(99)80008-0 [ Links ]

Fisher D 1994. Loneliness. In R Corsini (ed). Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 2). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Goffee R & Jones G 2004. What makes a leader? Business Strategy Review, 15(2):46-50. doi: 10.1111/j.0955-6419.2004.00313.x [ Links ]

Gumpert DE & Boyd DP 1984. The loneliness of the small-business owner. Harvard Business Review, 62(6):18-24. [ Links ]

Hart AW 1993. Principal succession: Establishing leadership in schools. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Masi CM & Cacioppo JT 2010. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year crass-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 25(1):132-141. doi: 10.1037/a0017805 [ Links ]

Herlihy B & Herlihy D 1980. The loneliness of educational leadership. NASSP Bulletin, 64(433):7-12. doi: 10.1177/019263658006443302 [ Links ]

Heystek J 2015. Principals' perceptions of the motivation potential of performance agreements in underperforming schools. South African Journal of Education, 35(2): Art. # 986, 10 pages. doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n2a986 [ Links ]

Hojat M 1982. Loneliness as a function of selected personality variables. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(1):137-141. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<137::AID-JCLP2270380122>3.0.CO;2-2 [ Links ]

Horowitz L, French R & Anderson C 1982. The prototype of a lonely person. In LA Peplau & DPerlman (eds). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Howard MP & Mallory BJ 2008. Perceptions of isolation among high school principals. Journal of Women in Educational Leadership, 6(1): Article 32. Available at http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1029&context=jwel. Accessed 10 November 2016. [ Links ]

Izgar H 2009. An investigation of depression and loneliness among school principals. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri [Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice], 9(1):247-258. Available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ837781.pdf. Accessed 10 November 2016. [ Links ]

Kaya D & Aydin H 2016. Elementary mathematics teachers' perceptions and lived experiences on mathematical communication. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 12(6):1619-1629. doi: 10.12973/eurasia.2014.1203a [ Links ]

Keshavarz N, Nutbeam D, Rowling L & Khavarpour F 2010. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: A new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Social Science & Medicine, 70(10):1467-1474. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.034 [ Links ]

Killeen C 1998. Loneliness: an epidemic in modern society. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(4):762-770. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00703.x [ Links ]

Lam LW & Lau DC 2012. Feeling lonely at work: investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(20):4265-4282. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.665070 [ Links ]

Lin CS 2013. Revealing the "essence" of things: Using phenomenology in LIS research. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML), 4:469478. Available at http://www.qqml.net/papers/December_2013_Issue/2413QQML_Journal_2013_ChiShiou LIn_4_469_478.pdf. Accessed 9 November 2016. [ Links ]

Lincoln YS & Guba EG 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Maxwell JA 2009. Designing a qualitative study. In L Bickman & DJ Rog (eds). The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Mercer D 1996. 'Can they walk on water?': professional isolation and the secondary headteacher. School Organisation, 16(2):165-178. doi: 10.1080/0260136960160204 [ Links ]

Meyer JP 2009. Commitment in a changing world of work. In HJ Klein, TE Becker & JP Meyer (eds). Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Moustakas CE 1961. Loneliness. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Naicker SR & Mestry R 2015. Developing educational leaders: A partnership between two universities to bring about system-wide change. South African Journal of Education, 35(2): Art. # 1085, 11 pages. doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n2a1085 [ Links ]

Oguz E & Kalkan M 2014. Relationship between loneliness and perceived social support of teachers in the workplace. Elementary Education Online, 13(3):787-795. Available at http://ilkogretim-online.org.tr/vol13say3/v13s3m5.pdf. Accessed 9 November 2016. [ Links ]

Patton MQ 2002. Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Peplau LA & Perlman D 1982. Perspectives on loneliness. In LA Peplau & D Perlman (eds). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Popper M 2011. Toward a theory of followership. Review of General Psychology, 15(1):29-36. doi: 10.1037/a0021989 [ Links ]

Reinking K & Bell RA 1991. Relationships among loneliness, communication competence, and career success in a state bureaucracy: A field study of the 'lonely at the top' maxim. Communication Quarterly, 39(4):358-373. doi: 10.1080/01463379109369812 [ Links ]

Robinson VMJ 2007. School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why (ACEL Monograph Series No. 41). Winmalee, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Leaders Inc. [ Links ]

Rogers C 1970. Carl Rogers on encounter groups. New York, NY: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Rokach A 2014. Leadership and loneliness. International Journal of Leadership and Change, 2(1): Article 6. Available at http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=ijlc. Accessed 9 November 2016. [ Links ]

Russell D, Cutrona CE, Rose J & Yurko K 1984. Social and emotional loneliness: An examination of Weiss's typology of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6):13131321. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.6.1313 [ Links ]

Saldana J 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Sarpkaya PY 2014. The effects of principal's loneliness in the workplace on their self-performance. Educational Research and Reviews, 9(20):967-974. doi: 10.5897/ERR2014.1847 [ Links ]

Sergiovanni T 2005. The principalship: A reflective practice perspective (5th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Şişman M & Turan S 2004. Bazi örgüsel degiskenler acisindan calişanlarm is doyumu ve sosyal-duygusal yalnizlik düzeyleri (MEB Şube Müdür Adaylari Üzerinde Bir Araştrrma) [A study of correlation between job satisfaction and social-emotional loneness of educational administrators in Turkish public schools]. Osmangazi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 5(1):117-128. Available at http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/ogusbd/article/view/5000080800/5000074900. Accessed 9 November 2016. [ Links ]

Smith DW 2011. Phenomenology. In EN Zalta (ed). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab. [ Links ]

Spillane JP & Lee LC 2013. Novice school principals' sense of ultimate responsibility: Problems of practice in transitioning to the principal's office. Educational Administration Quarterly. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13505290 [ Links ]

Stake RE 2010. Qualitative research: Studying how things work. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Stephenson LE 2009. Professional isolation and the school principal. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Washington, DC: George Mason University. [ Links ]

Streubert HJ & Carpenter DF 1999. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (2nd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Stroebe W, Stroebe M, Abakoumkin G & Schut H 1996. The role of loneliness and social support in adjustment to loss: A test of attachment versus stress theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6):1241-1249. doi: 10.1037/00223514.70.6.1241 [ Links ]

Tabancali E & Korumaz M 2015. Relationship between supervisors' loneliness at work and their organizational commitment. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(1):172-189. doi: 10.15345/iojes.2015.01.015 [ Links ]

Weiss R 1973. Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Wright S 2012. Is it lonely at the top? An empirical study of managers' and nonmanagers' loneliness in organizations. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 146(1-2):47-60. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.585187 [ Links ]

Wright SL 2005. Loneliness in the workplace. Unpublished PhD thesis. New Zealand: University of Canterbury. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35458935.pdf. Accessed 14 November 2016. [ Links ]

Wright SL, Burt CDB & Strongman KT 2006. Loneliness in the workplace: Construct definition and scale development. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 35(2):59-68. Available at https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/2751/12602927_Loneliness %20in%20the%20Workplace%20-Scale%20Developlment.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 8 November 2016. [ Links ]

Yahyaoglu R 2005. Yalnizlik psikolojisi: Kurt kapanindam huzur limanina... [Psychology of loneliness]. Istanbul, Turkey: Nesil Publication. [ Links ]

Yilmaz E & Altinok V 2009. Okul yöneticilerinin yalnizlik ve yaşam doyum düzeylerinin incelenmesi [Examining the loneliness and the life satisfaction levels of school principals]. Kuram ve Uygulamada Egitim Yönetimi [Educational Administration: Theory and Practice], 15(59):451-469. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2012. Applications of case study research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]