Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.36 n.4 Pretoria Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n4a1336

ARTICLES

Leadership development: A lever for system-wide educational change

Suraiya R Naicker; Raj Mestry

Department of Education Leadership and Management, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. snaicker@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The continuous poor performance of South Africa's learners is detrimental to its developing economy. The need for education change prompted two universities to initiate a system-wide change strategy in a poorly performing school district. The leverage for change was leadership development, involving school principals and district officials. The global impetus for driving leadership development is based on the positive association between high-quality leadership and effective schools. The change strategy was a three year leadership development intervention programme. An evaluative case study was used to investigate the experiences of the participants during the implementation of the programme. Research methods included individual interviews, observation, and a survey by means of a questionnaire. Using systems theory as a theoretical framework, various disconnections were identified in the school district. These disconnections concern the interrelationships between the educational leaders which hinder organisational learning. Changing the culture of the school district through system-wide collaboration could be the key to systemic improvements. Strategies such as collective capacity building, joint problem-solving, networking and system leadership, might provide the essential 'glue' for strengthening the interconnections within the school district.

Keywords: collective capacity building; district officials; education change; educational leadership; leadership development; principals; school district; system leadership; system-wide change

Introduction

South Africa is a developing economy that is in a transitional period to a fully-fledged democracy since the demise of apartheid in 1994. The redress of past inequalities, issues concerning equity and social justice are of current significance and pose a challenge for educational leaders. The extent of South Africa's education woes is explicated by Spaull (2013:3), who states that not only does the country have the "worst education system of all middle-income countries that participate in cross national assessments", but that the country performs "worse than many low-income African countries". These results present a bleak future for the South African economy and society, since a nation's education system influences the strength of its economy and society (Levin, 2012). Furthermore, the progress towards equity and social justice in education is alarming, since South Africa's historically disadvantaged learners have not improved their academic performance (Van der Berg & Louw, 2008), and continue to be marginalised by schools, universities and colleges (Bloch, 2009). As a result of having no further education post-secondary schooling, learners particularly in the 18 to 24 year age category, are at an economic disadvantage and face a high likelihood of unemployment (Spaull, 2013). This is a dark period in South Africa's history, which challenges the agency of school leaders to bring about change in the academic performance of learners.

Evidence suggests a positive link between high-quality leadership and successful schools (Bush & Jackson, 2002; Huber, 2004; Leithwood, Louis, Anderson & Wahlstrom, 2004). It was thus opportune for us to investigate a change strategy which used leadership development as leverage for change towards improving teaching and learning in a school district. Researching this change strategy is of global significance, firstly because theorists and researchers worldwide have shown interest in system-wide change approaches (Duffy & Reigeluth, 2008; Fullan, 2009a; Hopkins, Harris, Stoll & Mackay, 2010; Joseph & Reigeluth, 2005; Levin, 2012). Secondly, actual empirical cases of system-wide change approaches provide for the contestation of new ideas (Fullan, 2009a) and contribute to the body of change knowledge in education, and the development of theory pertaining to systemic change in school districts.

The system-wide change strategy researched was a three year leadership development intervention programme, named the Leadership for Learning Programme (LLP). System-wide change can be understood as targeting change broadly at the unit of the school district, rather than at the unit of schools. The programme aimed to build leadership capacity that would drive education change directed at improving teaching and learning in a school district. The LLP was an innovation borne of the partnership of two universities. One of the two universities involved was locally based, and the academics had knowledge of the local education context, while the other was an international university that offered intellectual capital and branding. Academics from the two universities approached the office of the Minister of the Executive Council (MEC) (parliamentary stature) who bought into the concept of the programme and selected the school district for the implementation of the programme. Of the fifteen school districts in Gauteng Province, the school district selected was marked by the recurring poor academic performance of learners in the National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations (Grade 12). Moreover, the school district involved in the study included communities with socio-economic challenges.

Against this background, the key research question is: what can be learnt about the implementation of a leadership development intervention programme based on system-wide change strategy? The sub-questions then, are: what are the experiences of the participants; what were the strengths and challenges of the programme; and, what can be learnt about the system-wide change process in a school district? The aim of our research was thus to explore and evaluate the implementation of a leadership development intervention programme based on a system-wide change strategy.

The Leadership for Learning Programme

Programme design, content and execution

The uniqueness of the school district with its various challenges and the novelty of the system-wide strategy steered the universities away from utilising previously designed models of leadership development programmes. Instead, a needs analysis was conducted in the school district from which various areas for leadership development, such as instructional leadership, emerged. The LLP followed an organic design commencing with a contact session based on instructional leadership. Overall, the LLP comprised four, week-long (twenty-eight hours) contact sessions held during school holidays, on-site support at schools and the district office, and monthly collaborative meetings of the participants who were clustered into groups. The contact sessions involved presentations, interactive small group sessions, and hands-on sessions based on various tools provided by the presenters. After each contact session, reflection and review of the programme was undertaken, which directed the future course of the programme. This enabled a large degree of flexibility that favoured the needs of the programme participants. The second contact session was based on the theme 'effective communication, leadership values and collaboration'. The third contact session dealt with 'leadership tools and strategic planning'. A reconnecting session was held over two days and the fourth contact session dealt with the topics ' data wise', ' charting the course' and ' instructional rounds'.

The LLP was dependent on external funding, which was largely successful. One-hundred-and-one (101) school principals and 44 district officials participated in the programme. Funding further enabled approximately 54 participants to attend a week-long leadership development programme at the international university. The 11 academic staff from both universities were responsible for coordinating the contact sessions, presenting some of the sessions and assisting cluster groups. Seven facilitators were hired to work with regional cluster groups, and to provide on-site support at schools and the district office. An administrator was responsible for the logistical aspects of the programme. Various experts, mainly from abroad, were arranged by the international university to deliver the contact sessions.

Literature Review

Movement towards system-wide change

The historical trajectory of education change shows a gradual shift towards system-wide change. Early change efforts occurred at the level of the teacher or individual school, and disregarding the district office as an agent of change (Chrispeels, Burke, Johnson & Daly, 2008). The model of change that regards the school as the unit of change, however, appears flawed. For instance, Harris (2010) argues that this model slows down the pace of change and is unsustainable over the long-term, while Hopkins et al. (2010) maintain that the model achieves limited success. The trend away from individualised school approaches to change at the larger system levels of school districts, provinces, and national levels, indicates a paradigm shift in the history of educational change. Policy-makers have come to realise that schools are nested in systems and that the linkages between the district office and its school sites may be vital to change efforts (Daly & Finnigan, 2011; Rorrer, Skrla & Scheurich, 2008).

The nature of system-wide change

System-wide change can be understood as change that occurs at "all schools simultaneously" (Fullan, 2009b:48), at either the national, provincial or district level of the school system. Hopkins (2011:10) explains the "systemic context" of a school, by pointing out that a school does not exist in isolation, but as a part of a broader educational system. It is important to understand the distinction between targeting change at an individual school level, and at the level of the system, where "what you're looking for is to have not only individual schools flourish, but also to cause multiple schools to improve simultaneously" (Fullan & Leithwood, 2012:17). The system-wide model is premised upon the capacity of all schools within the system to spur change as a collective force by means of communicating, connecting and aligning their efforts (Harris, 2010) resulting in a systemic effect. Systems theory was used to frame this research, and may provide a deeper understanding of system-wide change.

Theoretical Framework: Systems Theory

Systems are made up of interconnecting and "interdependent" parts (also referred to as sub-systems) that cause the system to have an "evolutionary" nature (Banathy & Jenlink, 2004:38). The basis of systems theory is that since parts of the system are linked to other parts, a significant change in one part will make it incompatible with other parts (Watson, 2006:24). Therefore, in order for change in one part of the system to succeed, there must be "significant complementary changes in the connected parts" (Duffy & Reigeluth, 2008:42). Seminal systems theorists Ackoff (1993) and Banathy (1992) advanced the notion that by connecting the parts of a system, the properties of the whole were greater than that of its parts. This part-whole relationship is referred to as synergy or the presence of synergism, which is similar to structural holism, where the whole is structurally, functionally and synergistically greater than the sum of its parts (Razik & Swanson, 2010).

In applying systems theory to the school district, developing leadership in a few schools (sub-systems) in an individualistic manner, may lead to some degree of change. However, developing leadership in a great number of schools and in a manner where leaders interact as a collective, would lead to a systemic change.

Leadership development

System-wide change is dependent on collective leadership capacity (Fullan, 2010; Harris, 2010). Leadership development, in order to build leadership capacity, is thus a crucial component of educational change. While the development and preparation of principals is widely supported (Bush & Jackson, 2002; Huber, 2004; Mestry & Singh, 2007), traditional methods of developing principals are individualistic, and their relevance in the current complex education context is questionable. For instance, psychometric testing, 360-degree feedback, psychologist interviews and mentoring discussions aimed at diagnosing individual strengths and weaknesses, are rational (Mabey & Finch-Lees, 2008). However, they fail to acknowledge the "duality of dialogic/constructivist epistemology, where the individual and the social context are mutually constitutive, discursive products of each other" (Mabey & Finch-Lees, 2008:234-235). Thus, Fullan's (2009b) notion of leadership development in three contexts, namely job-embedded learning, organisation-embedded learning and system-embedded learning, is significant. Job-embedded learning refers to providing support for principals at the school site where they can learn in context, which is where leadership development programmes appear to fall short (Rhodes & Brundrett, 2009). Problem-solving in context is conceptualised as the "situated" nature of learning, which enables practitioners to draw from their previous experience and knowledge in solving problems (Leithwood et al., 2004:67-68). Organisation-embedded learning emphasises that leaders should be enabled to develop schools into learning organisations, such that schools are able to "organise themselves to learn and problem solve all the time" (Fullan, 2009b:47). System-embedded learning is interactive learning throughout the district, including between the district office and schools, and across schools, by clustering schools and creating learning networks (Fullan, 2009b). The LLP was premised upon the concept of system-embedded learning. Research indicates that when school districts have been engaged in developing instructional leadership capacity at the school and district levels over the long-term, there is a significant improvement in learner performance (Leithwood et al., 2004).

South African principals are insufficiently trained and skilled for their expanding leadership and management roles, but professional development programmes are often fragmented, uncoordinated and even irrelevant (Mathibe, 2007). The Advanced Certificate in Education (ACE) for school principals was recently introduced by the South African Education Department to develop current and aspiring principals. Research revealed execution challenges with various components of the programme, such as the interactive sessions, mentoring processes and networking, however, there was overall support from both the participants and programme organisers for ACE to be made a mandatory qualification for new principals (Bush, Kiggundu & Moorosi, 2011).

System-wide change endeavours

There is a greater need for empirical research in system-wide (systemic) change based on actual cases. Joseph and Reigeluth (2005) implemented the Guidance System for Transforming Education (GSTE) in a school district in Indiana, in order to research how to improve the process of systemic change. Their work as facilitators of systemic change in school districts resulted in the development of a conceptual framework that posits six requirements for successful systemic change (Joseph & Reigeluth, 2010). These requirements are, as listed by Joseph & Reigeluth, "broad stakeholder ownership, learning organisation, understanding the systemic change process, evolving mindsets about education, systems view of education and finally systems design" (2010:97). Hopkins' (2011:5) research in a school district in Australia's state of Victoria, emphasises the importance of balancing both "bottom-up" and "top-down" approaches to change, since neither of the two approaches work separately. The findings further suggest that improvement across the system can be advanced by strengthening networking and by leaders assuming system-wide leadership roles (Hopkins, 2011).

Fullan (2001), cited in Groff (2009), rejected both top-down and bottom-up approaches as being ineffective and unsustainable, proposing instead a tri-level model. This model emphasises change at three levels, namely at school, district and state level, targeting the interactions between the three levels for sustainable improvement (Groff, 2009). Research by Harris (2010) found that the tri-level model in Wales, which used professional learning communities (PLCs) across and within the school district and state levels, had a positive impact on change, and generated collective capacity.

Research indicates that system leadership is an important strategy for advancing system-wide change (Boylan, 2013; Fullan, Bertani & Quinn, 2004; Hopkins & Higham, 2007). System leadership generally refers to persons in senior leadership positions, who extend their leadership beyond their own school, in order to support or change the practice of school leaders in other schools (Boylan, 2013). The essence of this concept is the transfer of information, knowledge, skills, innovation and best practice across the system (Harris, 2010:204).

Levin (2012), who reviewed empirical investigations of system-wide change over the past two decades, offers eight elements to consider for successful system-wide change. These can be summarised as: "goal-setting, positive engagement, capacity building, effective communication, learning from research and innovation, maintaining focus in the midst of multiple pressures, and use of resources", as well as "a strong implementation effort to support the change process" (Levin, 2012:11). Early research by Green and Etheridge (2001) found that effective systemic change is dependent upon educator involvement in decision making, changing mindsets that promote system thinking, collaboration between unions and districts, and movement away from authoritarian leadership to inclusive and collaborative approaches.

In engaging in system-wide change, Fullan (2011) cautions against using appealing, quick fix strategies that may not produce the desired results and that may even cause a situation to deteriorate. The flawed strategies are: using test results to hold educators accountable and to reward or punish teachers, promoting individual rather than group qualities, prioritising technology over instruction and using fragmented rather than systemic approaches (Fullan, 2011). What these strategies do not address, however, is changing the school culture, which can be done by means of strategies such as building capacity, collaborative practice, a focus on instruction, and systemic resolutions (Fullan, 2011).

There is limited empirical evidence of system-wide efforts to enhance educational leadership at national, provincial or district level in South Africa. Two system-wide change initiatives identified in the South African literature are the Systemic Enhancement for Education Development (SEED) programme and the Quality Learning Project (QLP) in De Aar (Fleisch, 2006). Neither study produced conclusive evidence of system-wide change. A programme that is currently under investigation is the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS), which aims to improve learning outcomes. After a two-year evaluation, Fleisch, Schöer, Roberts and Thornton (2016) report that numeracy scores were higher, with up to a .77 standard deviation, in the intervention schools. Further findings indicate benefits of using an approach combining lesson plans, learner resources, and the instructional coaching of teachers (Fleisch et al., 2016).

Research Design and Methodology

An evaluative case study was used to research the LLP (McDonough & McDonough, 1997), where the focus was on the process of implementation, and not on the expected outcomes of the intervention (Mouton, 2001). The case selection of the LLP for this research was due to the uniqueness of the venture, and the need for research in the area of system-wide change, where research opportunities are rare. Multiple methods of data collection were employed and included participant observation, individual interviews and a survey. The duality of using both qualitative and quantitative data positions case study as a research method that stands on its own, with its own design, data collection procedures and analytic techniques (Yin, 2012:19). Participant observation occurred during the four week-long contact sessions of the programme. Principals were further observed in three cluster group meetings. Interviews were conducted with five principals, four district officials, four academics and two facilitators towards the end of the three year programme. Overall, the interviewees comprised eight females and seven males. Simple random sampling was used in the selection of district officials, academic staff of the universities, and the programme facilitators for the interviews, while stratified random sampling ensured that one principal from each of the five geographical clusters of the school district was represented in the sample. Tesch's method (1990) cited in Creswell (2009) provided a systematic approach to the analysis of the qualitative data. This involved the identification of topics, the use of coding, the identification of categories, and the emergence of themes. To strengthen validity, the interviews were piloted with one principal, one district official, one academic and one facilitator. To promote reliability, the procedures followed in the study were carefully documented and a data base was developed. Furthermore, the interviews were recorded in order to reproduce accurate verbal transcripts and peer review was conducted with colleagues regarding the study procedure, the congruency of the findings, and the raw data (Merriam & Associates, 2002).

A standardised questionnaire was designed and administered at the conclusion of the programme. In developing the questionnaire, the researchers considered the topics and their constructs, which comprised the programme content during each of the contact sessions, themes from interview data gathered and analysed during the first two years of the programme's duration, the participant observation data for the first two years, and the literature. The first section of the questionnaire dealt with the biographical data of the respondents. The second section comprised of closed-ended statements pertaining specifically to the programme content. Participants were required to rate each concept/skill covered during the contact sessions on rating scales of 1 to 5, firstly, according to its level of importance and secondly, according to the skill level at which they thought they were competent. As it was the same persons who answered both importance and competence the paired t-test was used to compare them. For non-parametric data, the Wilcoxon Signed Ranked Test was used. Each of the items of importance and competence were subjected to a Principal Factor Analysis (PFA). The third section contained 28 closed-ended statements, and participants responded on a six-point Likert scale regarding their beliefs and attitudes concerning various aspects of the programme. In this section, a PFA was performed with items that had commonalities above 0.6 and average factor loadings greater than 0.6. The fourth section was made up of six open-ended questions, which gave the respondents greater freedom in conveying their views. The questionnaire was administered to 65 participants, based on participation and attendance records during the three years of the programme.

In the quantitative phase, descriptive and inferential numeric analysis was used (Creswell, 2009). The quantitative data was subjected to statistical and factor analysis procedures using the IBM Corporation (2012) SPSS Statistics version 21.0 computer software programme. Content validity was applied by review of the questionnaire by two peers, who were involved in the LLP from its conception, as well as an official statistician of the local university. The use of PFA enhanced the construct validity of the study. Reliability was measured using Chronbach's alpha, which is common practice for multiple-item measures of a concept (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). In this study, methodological triangulation of the qualitative and quantitative research methods was applied to strengthen internal reliability.

Ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the local university to undertake this research was obtained. Permission to conduct the research from the Gauteng Department of Education and the participating school district were secured. Research ethics procedures undertaken included the researchers being introduced to the participants of the LLP at a contact session, where the nature and aim of this investigation was explained. Informed, written consent from all the participating principals, district officials, academics and facilitators were obtained.

Findings

The qualitative data (observation and interview data) and the quantitative data were analysed separately. Thereafter, the researchers used methodological triangulation, by seeking convergence among the qualitative and quantitative findings. Four common themes resulted, namely: ineffective communication, leadership values, and collaboration; strengths of the LLP; challenges to the implementation of learning from the LLP; and changing mindsets. Each will now be discussed with references to the qualitative and quantitative findings.

Ineffective Communication, Leadership Values and Collaboration

There are ineffective communication, leadership values and collaboration in the school district. The quantitative data found that the most important difference between the importance and competence in each of the five contact sessions of the LLP was that pertaining to 'effective communication, leadership values and collaboration' between principals and the district office. This was evident from a comparison of the effect sizes for each contact session. As the effect size is a standardised value, one can compare the various contact sessions with one another, with respect to the difference between importance and competence. The larger this difference, the larger the effect size. 'Effective communication, leadership values and collaboration' was the contact session with the largest effect size (0.75). This finding indicates the relationship between principals and district officials to be inadequate, and is confirmed by the theme named 'poor interrelationships', identified in the qualitative findings. This theme has three sub-themes, namely, hierarchical structure of the school district, lack of collaboration, and tensions among district officials. The hierarchical structure of the school district influences district officials to adopt an authoritarian managerial approach, which hinders a collegial relationship between them. An academic remarked:

...I think most of the time, we were talking about better ways to work central office [district office] and principals, so that the principal is not the 'whipping boy' and the central office was not 'the demon'... The principal was in charge in the building and the central office said, 'jump!' and you were supposed to say, 'how high?'

The hierarchical structure of the district office, entrenched in an overly bureaucratic approach, causes frustration to both principals and district officials, and detracts from the principal's role as instructional leader. Johnson and Chrispeels (2010) contend that excessive bureaucratic control, while neglecting communication and relational linkages between the school district office and schools, can hinder change efforts. A facilitator expressed the following view:

The district officials, of course, would say that the principals of the schools do not follow the instructions that they are given [. ] they were complaining about all the administrative things. And the teachers [principals] on the other hand would say, but our job is to teach, not filling out forms. We not clerks [sic]. We don't have to do this. So it was a lot of conflict there [. ] there was mudslinging, but from both sides.

The second sub-theme, 'lack of collaboration', is prevalent among the departmental units in the district office, as well as among principals within the district. This is evident in the district official's non-alignment of diaries and a lack of team work, resulting in disorganisation and frustration. A district official stated, "I've got no idea what curriculum is doing. Curriculum has got no idea what I'm doing' while a principal stated, "you sit like an island when you [sic] a principal and you don't know what's going on in other schools'" People who are unware of systems thinking disregard their interconnectedness (Reynolds & Holwell, 2010:6). This is detrimental since a team that is unaligned is wasted energy, and as a team aligns itself, synergy is developed (Senge, 2006).

The third sub-theme was 'tensions among district officials' which flared up during the LLP. The favouritism of officials and inadequate participative decision making processes were the underlying causes of the conflict during the LLP. The qualitative data reveal that the LLP provided an outlet for district officials to vent their frustrations. An academic voiced this view:

I thought we would be working on knowledge [. ] Not understanding that you have to toil the soil first, and get people ready to receive and there are rocks, there's lots of trash that's in there, based on, you know, past experiences. There are all different kinds of flowers and they don't really know each other. [sic]

The quantitative data indicated that the most important difference between the importance and competence of the factor, ' effective communication, leadership values and collaboration in the school district', as indicated by the effect sizes of the five items of the second contact session, is that regarding 'the difficult conversation: dealing with tough issues in the district office or school'. The LLP assisted in addressing the tensions by providing the participants with various practical conflict management tools by means of which to enable them to address the issue of difficult conversations. An academic recalls:

.she [presenter] taught them how to have difficult conversations. She set the norms for that, it was built on, you know, it used many of the negotiation strategies that she had taught them [...] she found a level of common ground, it was a baby step but a) everybody felt that they were heard b) she managed to take, bring them down the ladder of inference [ . ] she laid the ground rule and it changed everything.

Change is possible when the root of the problem that harms relationships is directly challenged (Jansen, 2009).

Strengths of the LLP

The common theme 'strengths of the LLP' yielded three sub-themes, namely, promoting collaborative practice, enhanced professional development, and the partnership with the international university.

Promoting collaborative practice

The LLP promoted greater interaction among principals and among district officials, improving their relationships with each another. District officials began moving away from their authoritarian attitudes towards the principals that had earlier been exhibited in the LLP. These relationships were further enhanced when the principals and district officials shared the experience of travelling abroad to the international university. A facilitator remarked:

...the strengths of the programme was getting to get the district officials and the teachers and principals in the same venue with the same heartbeat, because that is also unheard of... there's always been us and them. and there were times that I felt that they felt absolutely equal and they could relate to exactly the same problems and they could own up that they have both messed up, somewhere along the line.

The qualitative findings further revealed that the LLP initiated the practice of networking and system leadership among principals. Networking and meeting in small cluster groups assisted in the sharing of best practice and joint problem-solving. A facilitator shared the following perspective:

If I can mention that the group, you know, grew to the extent that they were working as a team, even supporting one another, even addressing, you know, their issues and you know, trying to assist where they could.

From the five leadership tools that were discussed in the third contact session, joint problem-solving was found to have the largest effect size of 0.62, and thus an area where the participants could be further developed.

The quantitative findings support the qualitative findings. When the 28 items of section three of the questionnaire was subjected to a PFA, four factors emerged and these were named ' enriched professional practice', 'the enhancement of collaboration' , ' enhanced personal development' and ' improved understanding of the district.' In the factor, 'enhanced personal development', the item: ' the programme has enabled me to learn from the other participants' , has the highest mean score (5.28). The factor 'the enhancement of collaboration' has two items with strong mean scores, one being the item: 'the programme has enabled me to collaborate with my colleagues on matters pertaining to teaching', which has a mean of 5.00, and the other being the item: 'the programme has enabled me to establish networks with other participants', which has a mean of 5.02. Hopkins et al. (2010:16) states that systemic change "depends on excellent practice being developed, shared, demonstrated and adopted across and between schools".

These four first-order factors were subjected to a second-order procedure since the KaiserMeyer-Olkin (KMO), which is a measure of sampling adequacy, was 0.787 and Bartlett's sphericity value was p < 0.0005, thus indicating that a more parsimonious grouping is possible. One factor resulted, which was named ' perceived benefits of the leadership for learning programme.' It contains 27 items and has a Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient of 0.978. The perceived benefits of the LLP is thus built on the foundation of four factors, namely 'Enriched professional practice', 'The enhancement of collaboration', 'Enhancing personal development' and 'Improved understanding of the district'. A process of linear regression, where the programme strives to find the line that best fits the data, was used to predict the importance of the particular factor in the outcome variable, namely perceived benefits of the LLP (FB2.0). As indicated in Table 1, 'the enhancement of collaboration' (Item FB1.2) is predicted as the second best contributor to the factor, The Perceived Benefits of the LLP due to the resultant Beta value of .258. If the Beta value increases by one standard deviation, the outcome of the factor, 'perceived benefits of the LLP' , will increase by .291 deviations.

A further finding from the questionnaire's open question regarding the programme's most effective feature was found to be collaboration as reported by 54% of the respondents.

A barrier to collaborative practice among schools is that finding a common time for principals to meet is problematic, due to principal's demanding work schedules. Furthermore, there are insufficient collaborative structures in the school district to promote collaborative practice. It is the role of district office leaders to initiate and maintain cross-school collaboration so that connections between teams, groups or clusters of leaders can develop and leaders can learn from each other's work (Fullan, 2010).

Enhanced professional development

The LLP contributed to the participants' professional development. Table 1 indicates that item FB1.1, 'enriched professional practice', is predicted as the best contributor to the dependent variable 'perceived benefits of the LLP', with a Beta value of .445. If the Beta value increases by one standard deviation, the outcome of the factor, 'perceived benefits of the LLP' will increase by .492 standard deviations.

While participants agreed to strongly agreed with most of the items in the first-order factor, ' enriched professional practice', the two items with the highest mean scores were: ' the programme has inspired me', with a mean score of 5.29, and 'the programme has challenged me intellectually' , with a mean score of 5.25.

The qualitative data supported the finding that the LLP enhanced the professional development of the participants. One of the qualitative sub-themes is professional development. Participants built leadership capacity for instructional leadership, which took principals out of the office into the classrooms on instructional rounds. It is important to note that the quantitative data indicates that instructional leadership is an area in which participants require further training, as it had the second largest effect size (0.74) when the various contact sessions are compared with one another with respect to the difference between importance and competence. Other aspects of development with which principals and district officials felt better equipped are data interpretation, conflict management, and formulating theories of action. Principals feel empowered to manage complex challenges in schools, an area that they said had been neglected in previous induction programmes by their employers. Empowering principals with high quality teaching materials is important, as it might take a longer time to build people's capacity to bring about considerable change (Fullan, 2007).

Effective communication skills were put into practice by the district officials, and a more collegial approach is adopted towards working with principals. A district official stated:

...I've learned that as well, to become a little bit less defensive... I've learned from obviously get more involved with my people, in terms of where they are, be with them. And a very important thing is not to be up there, talk down there. You are just as strong as they are and therefore you need to work as if you are on that level. [sic]

The partnership with the international university

The partnership between the two universities was a strength of the LLP. One benefit of the partnership with the international university was the high quality of presenters, which had a great impact on the participants. This is supported in the quantitative findings pertaining to the overall feedback of the LLP, where the item, ' the programme has utilised presenters of good quality' , had the highest mean score (5.32) of all the items. The qualitative data indicate that the effectiveness of the presenters is due to the interactive pedagogy used, the authenticity of presenting work that formed part of their research field and their own experience, the relevance and practicality of the tools provided and their ability to adapt their facilitation skills to what was happening in the moment. An academic noted:

They were all speaking from their own experience, their own research, so they weren't speaking from 'book knowledge'. So in that sense, it had emotive [sic] value, rather than purely cognitive value...

Challenges to the Implementation of Learning from the LLP

The transfer of learning from the contact sessions of the LLP to school sites is a challenge. A quantitative finding is that the least effective feature of the LLP is how the transfer of learning is implemented at schools. This finding was elicited from 31% of the participants in an open question posed in the questionnaire. Participants (18%) suggested that there could be better monitoring, mentorship and support at schools. There is thus a need for greater focus on the concept of job-embedded learning (Fullan, 2009b), which was identified as an area where leadership programmes appear to flounder (Rhodes & Brundrett, 2009). The qualitative findings indicated that there were long gaps between contact sessions. Therefore, there was a need for more frequent contact with the participants. Both the quantitative and qualitative data show that the school district needed to have bought-in to the programme before it commenced. An academic stated:

.we need to ensure that we have buy-in from the beginning. We have to let them [the district] know they are equal partners, because I got the feeling initially that to them, it seemed as if we are [sic] being imposed on them.

Changing mindsets

Qualitative and quantitative evidence indicate that the participants underwent mindset changes when they discovered that the educational challenges that confronted them were universal. Being limited to their local contexts, the LLP participants believed that they alone faced complex challenges. Through interaction with other practitioners, both locally and abroad, during the course of the LLP, they became aware that the complexities in their schools also existed internationally. Once the participants realised this, they underwent a mind shift that gave them new hope. A principal remarked:

.that gave you little bit of confidence [. ] that what I'm experiencing, other people are going through the same problems. And then this programme enabled us now to start communicating and learning from each other and learning to deal with the challenges [. ] It really made you feel like that helplessness, you know, was taken away. You felt like, you know what, there's hope and I can go back and I can continue.

Mindset changes are "mental models or outlooks from which people approach problems", which is deemed a necessity for systemic change (Richter & Reigeluth, 2007:4).

Discussion

Successful change efforts require the individual parts of the system to come together and form a network of connections (Daly & Finnigan, 2011). However, interconnections between the important role players in the school district were grossly inadequate, contributing to a lack of synergism, which hinders the optimal functioning of the system (Razik & Swanson, 2010). A dominant top-down approach from the district office appears to hinder organisational learning (Chrispeels et al., 2008). Hopkins (2011) suggests balancing the top-down approach by using a bottom-up approach, which entails moving away from government prescription towards greater educator professionalism in driving change.

The LLP was a vehicle for improving the poor relationships that existed between principals and district officials. As the programme unfolded, district officials and principals began to understand each other's challenges. As supported by systems theorists Ackoff (1993) and Banathy (1992), district and school leaders need to understand that the nature of their relationship is based on interdependence, and that the more connected they are, the more the system is likely to benefit in its movement towards systemic change.

A lack of collaborative practice and structures for principals within the district promotes isolated work practices among principals. The lack of collaboration results in principals' feeling helpless. By means of interaction with the other participants in the LLP, and the exposure to international challenges in education, the participants underwent a mindset change moving them from disillusion to hopefulness. This change can be understood as moving from a view of being disconnected from the world to being a part of the world (Senge, 2006). The lack of collaborative opportunities further prevents organisational learning. Developing a learning organisation supersedes all the elements of a systemic change process (Joseph & Reigeluth, 2010), for, in order to achieve stability in the face of continuous change, learning is "the single most important resource for organisational renewal in the post-modern age" (Hargreaves, 1995

cited in Mulford, 2005:336). The LLP initiated collective capacity building by providing sessions for joint problem solving, and sparked networking among participants, thus forging systemic links. This further draws attention to the mode of delivery of the programme, which included opportunities for interactive activities. Fullan (2009b) espouses system-embedded learning, which is interactive learning throughout the district, including between the district office and schools, and across schools by clustering schools and creating learning networks. We believe that school district office leaders can play a greater role in initiating and maintaining cross-school collaboration, so that connections between teams, groups or clusters of leaders can develop, and leaders can learn from each other's work (Fullan, 2010). This may facilitate system leadership, which in turn will advance system-wide change (Boylan, 2013).

A problematic aspect of the LLP was its implementation at the school site. Whilst there is evidence that some principals share their new learning with their staff, there is also data indicating that some principals do not work well with their staff. Levin (2009) pointed out the importance of an effective implementation process to support a change initiative. Fullan (2007) further explains that the change process consists of three phases: the initiation of change, the implementation of change and the institutionalisation of change. The implementation phase is important, as it will influence whether the change is successful or not.

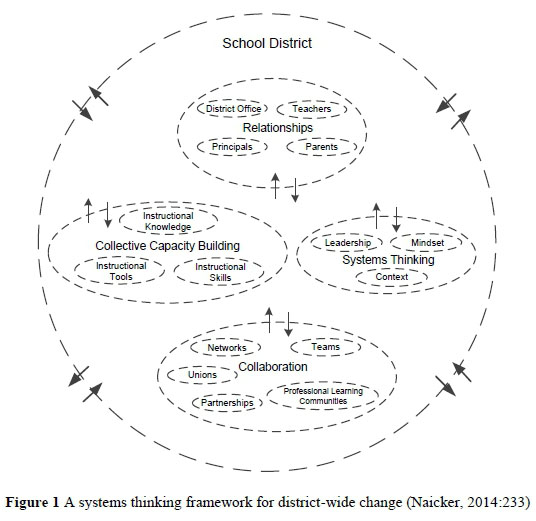

This study led to the development of a systems thinking model for district-wide change (Figure 1). Representing the broad findings in a systems model is significant for education research, because it leads to a deeper understanding of the complexities in school systems. We are of the opinion that systems thinking is insufficiently utilised in educational research, and is an essential tool for educational leaders in the contemporary era.

The systems model in Figure 1 fuses all the components and sub-components required for district-wide change into a coherent whole. Representing all these elements in a systems model reminds us that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts (Senge, 2006).

This systemic model depicts the key interrelationships, which are not interrelationships among people, but among the key variables. These variables, or sub-systems, are collaboration, collective capacity building, systems thinking and relationships. The arrows represent the interaction of the elements. The broken lines indicate that the system is open and interacts with its internal and external environment. Using a systems model enables one to understand that if a school district is unable to promote successful education outcomes for learners, the system's output negatively affects the external environment, which includes the economy. Manifestations of poorly performing education systems in South Africa, which are detrimental to the developing South African economy, are the high unemployment rate, excessive unskilled labour and remuneration inequality (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2013).

Conclusion

This research contributes to the global discourse on education change. The LLP provided an actual case of a system-wide change strategy in its implementation phase. The main learning about system-wide change that arose from this research is that if the interrelationships between the elements of a system are weak, it is unlikely that a system will succeed. While school districts in South Africa are making efforts to implement interventions and policies directed at improving educational outcomes, the question arises as to whether they are missing ' the big picture'. This picture concerns changing the very culture of the school district to include aspects such as fostering collaboration between education leaders, developing healthy interrelationships, engaging in collective capacity building, promoting joint problem solving, spurring networking and encouraging system leadership. These aspects may provide the essential 'glue' for bonding the links required for system improvement. Notably, system-wide collaboration was deemed the appropriate intervention for moving school systems from great to excellent in the well-known McKinsey study (Mourshed, Chijioke & Barber, 2010).

Future research can be undertaken to investigate the longer-term impact of the LLP. This research urges change agents such as policymakers, activists for social justice, economists, researchers and practitioners to consider the merits of system-wide strategies for future education change efforts in educational leadership.

Note

i Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Ackoff R 1993. From mechanistic to social systems thinking. Paper presented at the Systems Thinking in Action Conference, November. Available at http://acasa.upenn.edu/socsysthnkg.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2014. [ Links ]

Banathy BH 1992. A systems view of education: Concepts and principles for effective practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Banathy BH & Jenlink PM 2004. Systems inquiry and its application in education. In DH Jonassen (ed). Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Bloomington, IN: Association for Educational Communications and Technology. [ Links ]

Bloch G 2009. The toxic mix: What's wrong with South Africa's schools and how to fix it. Cape Town, South Africa: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Boylan M 2013. Deepening system leadership: Teachers leading from below. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1741143213501314 [ Links ]

Bush T & Jackson D 2002. A preparation for school leadership: International perspectives. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 30(4):417-429. doi: 10.1177/0263211X020304004 [ Links ]

Bush T, Kiggundu E & Moorosi P 2011. Preparing new principals in South Africa: the ACE: School leadership programme. South African Journal of Education, 31(1):31-43. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/356/236. Accessed 9 October 2016. [ Links ]

Chrispeels JH, Burke PH, Johnson P & Daly AJ 2008. Aligning mental models of district and school leadership teams for reform coherence. Education and Urban Society, 40(6):730-750. doi: 10.1177/0013124508319582 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Daly AJ & Finnigan KS 2011. The ebb and flow of social network ties between district leaders under high-stakes accountability. American Educational Research Journal, 48(1):39-79. doi: 10.3102/0002831210368990 [ Links ]

Duffy FM & Reigeluth CM 2008. The school system transformation (SST) protocol. Educational Technology, 48(4):41-49. [ Links ]

Fleisch B 2006. Education district development in South Africa: A new direction for school improvement? In A Harris & JH Chrispeels (eds). Improving schools and educational systems: International perspectives. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fleisch B, Schöer V, Roberts G & Thornton A 2016. System-wide improvement of early-grade mathematics: New evidence from the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy. International Journal of Educational Development, 49:157-174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.02.006 [ Links ]

Fullan M 2007. The new meaning of educational change (4th ed). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2009a. Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Education Change, 10(2):101-113. doi: 10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z [ Links ]

Fullan M 2009b. Leadership development: The larger context. Educational Leadership, 67(2):45-49. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2010. All systems go: The change imperative for whole system reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Fullan M 2011. Choosing the wrong drivers for whole system reform. Series Paper No. 204. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Strategic Education. Available at http://www.schoolclimate.org/climate/documents/policy/school-reform-drivers.pdf. Accessed 2 October 2013. [ Links ]

Fullan M, Bertani A & Quinn J 2004. New lessons for districtwide reform. Educational Leadership, 61(7):42-46. [ Links ]

Fullan M & Leithwood K 2012. 21st Century leadership: Looking forward. In Conversation, IV(I):1 -22. Available at http://michaelfullan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/13557615570.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2016. [ Links ]

Green RL & Etheridge CP 2001. Collaborating to establish standards and accountability: Lessons learned about systemic change. Education, 121(4):821-829. [ Links ]

Groff J 2009. Transforming the systems of public education. Available at http://www.jengroff.net/pubs_files/TransformingSystems-PublicEducation_GROFF-NMEF.pdf. Accessed 14 April 2016. [ Links ]

Harris A 2010. Leading system transformation. School Leadership & Management, 30(3):197-207. doi:10.1080/13632434.2010.494080 [ Links ]

Hopkins D 2011. Powerful learning: taking educational reform to scale. Paper No. 20. Melbourne, Australia: Education Policy and Research Division. Available at http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/research/hopkinspowerfullearning.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

Hopkins D, Harris A, Stoll L & Mackay T 2010. School and system improvement: State of the art review. Keynote presentation prepared for the 24th International Congress of School Effectiveness and School Improvement, Limassol, Cyprus, 6th January 2011. Available at http://www.icsei.net/icsei2011/State_of_the_art/State_of_the_art_Session_C.pdf. Accessed 21 August 2016. [ Links ]

Hopkins D & Higham R 2007. System leadership: mapping the landscape. School Leadership & Management, 27(2):147-166. doi: 10.1080/13632430701237289 [ Links ]

Huber SG 2004. School leadership and leadership development: Adjusting leadership theories and development programmes to values and the core purpose of school. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(6):669-684. doi: 10.1108/09578230410563665 [ Links ]

IBM Corporation 2012. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation. [ Links ]

Jansen JD 2009. When politics and emotion meet: Educational change in racially divided communities. In A Hargreaves & M Fullan (eds). Change wars. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree. [ Links ]

Johnson PE & Chrispeels JH 2010. Linking the central office and its schools for reform. Education Administration Quarterly, 46(5):738-775. doi: 10.1177/0013161X10377346 [ Links ]

Joseph R & Reigeluth CM 2005. Formative research on an early stage of the systemic change process in a small district. British Journal of Educational Technology (BJET), 36(6):937-956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00566.x [ Links ]

Joseph R & Reigeluth CM 2010. The systemic change process in education: A conceptual framework. Contemporary Educational Technology, 1(2):97-117. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Charles_Reigeluth/publication/291827633_ The_Systemic _Change_Process_in_Education_A_Conceptual_Framework/links/56a6720a08ae6c4 37c1aefcc.pdf. Accessed 9 October 2016. [ Links ]

Leithwood K, Louis KS, Anderson S & Wahlstrom K 2004. How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. Available at http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/How-Leadership-Influences-Student-Learning.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

Levin B 2009. Reform without (much) rancor. In A Hargreaves & M Fullan (eds). Change wars. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree. [ Links ]

Levin B 2012. System-wide improvement in education. Education Policy Series 13. Belgium: The International Academy of Education. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002180/218001E.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

Mabey C & Finch-Lees T 2008. Management and leadership development. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Mathibe I 2007. The professional development of school principals. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):523-540. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/111/38. Accessed 9 October 2016. [ Links ]

McDonough J & McDonough S 1997. Research methods for English language teachers. London, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]

Merriam SB & Associates 2002. Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mestry R & Singh P 2007. Continuing professional development for principals: a South African perspective. South African Journal of Education, 27(3):477-490. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/112/35. Accessed 9 October 2016. [ Links ]

Mourshed M, Chijioke C & Barber M 2010. How the world's most improved school systems keep getting better. New York, NY: McKinsey & Company. [ Links ]

Mouton J 2001. How to succeed in your master's and doctoral studies: A South African guide and resource book. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Mulford B 2005. Organisational learning and educational change. In A Hargreaves (ed). Extending educational change: International handbook of educational change. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Naicker SR 2014. A case study of an educational leadership development intervention programme for public school principals and district officials in a school district in Gauteng. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Johannesburg. Available at https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Repository/uj:13789?f0=sm_creato r%3A%22Naicker%2C+Suraiya+Rathankoomar%22. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

OECD 2013. OECD economic surveys: South Africa 2013. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Available at http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/other/OECD%20Economic%20Surveys %20South%20Africa%202013.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

Razik TA & Swanson AD 2010. Fundamental concepts of educational leadership & management (3rd ed). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Reynolds M & Holwell S 2010. Introducing systems approaches. In M Reynolds & S Holwell (eds). Systems approaches to managing change: A practical guide. London, UK: Springer. [ Links ]

Rhodes C & Brundrett M 2009. Leadership development and school improvement. Educational Review, 61(4):361-374. doi: 10.1080/00131910903403949 [ Links ]

Richter KB & Reigeluth CM 2007. Systemic transformation in public school systems. The F. M. Duffy Reports, 12(4):1-21. [ Links ]

Rorrer AK, Skrla L & Scheurich JJ 2008. Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3):307- 357. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08318962 [ Links ]

Senge PM 2006. The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization (revised ed). London, UK: Random House, Inc. [ Links ]

Spaull N 2013. South Africa's education crisis: The quality of education in South Africa, 1994-2011. Report commissioned by CDE. Johannesburg, South Africa: Centre for Development and Enterprise. Available at http://www.section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Spaull-2013-CDE-report-South-Africas-Education-Crisis.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016. [ Links ]

Tavakol M & Dennick R 2011. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education (IJME), 2:53-55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [ Links ]

Van der Berg S & Louw M 2008. South African student performance in regional context. In G Bloch, L Chisholm, B Fleisch & M Mabizela (eds). Investment choices for South African education. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Watson W 2006. Systemic change and systems design. TechTrends, 50(2):24. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2012. Applications of case study research (3rd ed). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]