Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.36 no.2 Pretoria may. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n2a1246

The management of user fees and other fundraising initiatives in self-managing public schools

Raj Mestry

Department of Education Leadership and Management, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. rajm@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In view of redressing past imbalances created by the apartheid regime and achieving equity in funding public schools, the post-1994 government introduced the Norms and Standards for School Funding policy that severely reduces state funding to schools located within affluent areas. However, the South African Schools Act, No. 84 of 1996 makes provision for school governing bodies (SGBs), responsible for financial and physical resource management of schools, to supplement state funding. In order to ensure that effective teaching and learning takes place, self-managed SGBs secure funding from parents, corporates and the broader community through school (user) fees, donations and unconventional fundraising projects. These additional funds enable SGBs to provide schools with state-of-the-art physical resources, and to employ teaching and nonteaching staff not provided for in the post-provisioning norms determined by the department of education. Using quantitative research, this study aimed to determine how self-managed SGBs manage funds through user fees and other fundraising initiatives. Findings revealed that governing bodies of most self-managed schools were able to secure substantial funding from school fees and other fundraising initiatives, and managed the funds effectively and efficiently.

Keywords: financial management; norms and standards; quintiles; resource management; school fees; school funding; selfmanagement

Introduction and Background to the Problem

Decentralisation is considered to be one of the dominant themes in educational change. This requires a shift towards 'autonomous school' (Theodorou & Pashiardis, 2015:73). According to Anderson and Lumby (2005) and Bush and Heystek (2003), many countries have devolved considerable power to schools. Site-based management is considered to be a significant reform initiative that attempts to place greater authority in individual schools through the adoption of a democratic decision-making process. Deming (1994) and Parker and Leithwood (2000) assert that the primary goal of site-based management in schools is to shift authority away from the district administrative hierarchy, into the hands of stakeholders (such as teachers and parents), who are more closely connected to the school and probably better equipped to meet the specialised needs of learners. Site-based management encourages a high-involvement management approach, which holds that stakeholders perform best in an environment where they are deeply involved in ongoing improvements of the organisation and committed to its success (Drury, 1999). However, it should be emphasised that increased autonomy is matched by a greater emphasis on accountability (Glatter, Mulford & Shuttleworth, 2003). According to Brauckmann and Schwarz (2014), enhanced decision-making opportunities and increasing demands for accountability call for new school-level structures that take on more responsibility. This is intended to improve quality by strengthening school autonomy, accompanied by development processes initiated and governed by schools themselves.

Daun (2011 in Theodorou & Pashiardis, 2015), asserts that the areas of decision-making delegated by education authorities to schools refer mostly to the organisation of teaching and the management of personnel, school property and school finances. Marishane and Botha (2004) assert that educational reform in a democratic South Africa has been highlighted by the introduction of the South African Schools Act (Republic of South Africa, 1996) (hereafter the Schools Act). Marishane (2003) posits that it is the responsibility of the state to empower the relevant structures within schools to enable them to effectively manage allocated funds. This necessitates the state to relinquish some control, and allow schools to operate independently, with less external interference and fewer restrictions. Sections 36 and 43 of the Schools Act make it mandatory for schools to manage the schools' funds and to take responsibility for implementing all the necessary financial accountability processes. The additional functions reflected in Section 21 of the Schools Act (discussed below) make provision for education to be placed firmly on the road to a site-based system, where schools can become increasingly self-managed (Department of Education [DoE], South Africa 1996). Decentralising the functions of financial management and affording a potentially large-range of financial decision-making powers to SGBs has become an important strategy aimed at school improvement and school effectiveness (Marishane & Botha, 2004). Van Deventer and Kruger (2003) concur that the approach of decentralising the functions of financial management to public schools provides educational stakeholders (teachers, parents, learners and the broader community) with the opportunity and power to improve and develop their schools. Research reveals that devolved decisionmaking powers allow SGBs to respond more quickly to the changing needs and priorities of schools (Gann, 1998; Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009; Van Wyk, 2007).

According to Van Rooyen (2012) and Van Wyk (2007), the shift to decentralised school governance requires SGB members to develop a wide range of knowledge, skills and capacity to deal with the complex issues and tasks they are expected to fulfil. Inevitably, issues of finance and budgeting take up a large proportion of SGB governors' time, in particular because SGBs have the authority to develop and implement the school' policy, draw up budgets, and set and collect school fees (Bush & Heystek, 2003). Unquestionably, site-based management results in increased accountability for SGBs, who are entrusted with managing the financial and physical resources of public schools (Mestry, 2004; Xaba & Ngubane, 2010). According to Botha (2012), accountability in self-managed schools reduces the risk of funds being mismanaged or misappropriated through corruption and other related fraudulent practices. This implies a profound change in the culture and practice of schools, and it therefore becomes imperative for SGBs, school management teams (SMTs) and principals (who evidently serve on both SGBs and SMTs), to have sound financial knowledge and skills by means of which to manage their schools' financial and physical resources effectively, efficiently and economically. This ensures that SGBs take appropriate steps to prevent any unauthorised, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure (Republic of South Africa, 1999).

However, while enabling or driving forces for decentralisation and self-management are emphasised, hindering forces are also prevalent. A number of negative effects appear to hamper the successful implementation of site-based management. These include an increased burden on school leaders, a widening of social inequalities, and an increased possibility of fraud and misuse of public funds (Theodorou & Pashiardis, 2015). These are often attributed to the way funding is utilised and to the adoption of ineffective financial management practices. In South Africa, the inappropriate selection of parents to serve on SGBs, principals' leadership styles and environmental factors, such as parents' socio-economic status, are likewise factors detrimental to the provision of quality education. Media reports reflect on the way in which principals and SGBs have become entangled in financial mismanagement through misappropriation, fraud, pilfering of cash, theft, poor record keeping and improper financial controls (Mestry, 2004; Mtshali, 2012; Phaladi, 2015). It can thus be argued that decentralisation of school governance brings with it the possibility of extreme inequality due to parents and teachers not having the knowledge and resources to adequately exercise the financial management of their children's schooling (Van Langen & Dekkers, 2001 in Tsotetsi, Van Wyk & Lemmer, 2008).

Nevertheless, the concept of self-managed schools is significant for the transformation of the post-apartheid South African school system, as well as education systems in developing countries plagued with major challenges in school funding and the provision of quality education. This study emphasises the importance of self-managed schools accumulating funds through school (user) fees and unconventional fundraising initiatives, and effectively managing these funds. Research has shown that well-resourced schools contribute to excellent learner performance and the achievement of sound educational outcomes (Levačić & Vignoles, 2002; Van der Berg, 2006).

Most schools located within affluent suburbs and inner-city areas have elected to be selfmanaged in contrast to the many schools in townships and rural areas that are dependent on education district offices to manage their schools' finances (Mestry, 2006; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2008). To be self-managed, SGBs are required to apply for additional functions to the provincial Head of Department, in terms of section 21 of the Schools Act. These functions include:

• maintaining and improving the school's property, buildings, grounds and hostel;

• determining the extra-mural curriculum and the choice of subject option in terms of provincial curriculum policy;

• purchasing textbooks, educational materials or equipment for the school; and

• paying for municipal services provided to the school.

The DoE applies criteria such as determining the capacity of SGBs and the timely submission of financial statements annually to the DoE, in order to grant schools these additional functions. At the beginning of each academic year, the provincial DoE earmarks an amount for the procurement of physical resources and learning and teaching support materials (LTSM) for each school under their administration, and deposits the amount directly into the so-called 'section 21' school's banking account (Bisschoff & Thurlow, 2005; Van Rooyen, 2012). Although governing bodies are required to spend the state's resource allocation according to the prescriptions of the provincial head of department, some financial freedom is conferred to these schools (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009; Van Rooyen, 2012). Schools acquiring section 21 functions have the advantage of selecting their own suppliers, rather than relying on the district offices. They have the opportunity of negotiating better prices and obtaining substantial discounts from suppliers. In the event that funds are not fully utilised in the assigned financial year, the unspent funds may be utilised in the following financial year.

Research reveals that schools that have been granted section 21 functions perform much better financially (Van Wyk, 2007). Most of these schools are in a position to recruit governors with good communication and financial skills, for example, preparing and managing school budgets (OECD, 2008). Many parents of self-managed schools usually take an interest in school affairs and will choose competent, dedicated and hardworking people to serve on their SGBs. Research conducted by Karlsson (2002) shows that many self-managed schools have strong parent components serving on the SGBs, who undertake their responsibilities seriously. The findings also revealed that principals of self-managed schools still play a dominant role in meetings and financial decision-making. This is attributed to the principal's position of power within the school, levels of education in contrast to parent governors, having first access to information received from the education authorities, and because principals are delegated the authority to execute decisions taken at SGB meetings.

On the other hand, schools that are not conferred section 21 functions (the so-called 'nonSection 21' schools) receive their resource allocation in the form of a 'paper budget'. These schools are dependent on the district offices for the procurement of LTSM, defraying the cost of repairs and maintenance, and paying for services rendered to the school. The unspent funds in a particular financial year are transferred to the national treasury since no rollover of the budget is applied (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009).

Most of the historically advantaged schools (mostly former Model C) have been subjected to severe cutbacks in state funding. These schools, financially advantaged under the pre-1994 school dispensation in South Africa, have adequate resources to provide quality education (Fiske & Ladd, 2005; Motala, 2011). However, to sustain their school funds and continue to provide effective education, most of the SGBs resort to aggressive marketing and fundraising initiatives. The schools' budgets are substantial and make provision for the salaries of additional teachers above the postprovisioning norm determined by the DoE, state-of-the-art resources, safety and security, extramural activities and stationery. The SGBs are thus compelled to charge exorbitant school fees and resort to numerous fundraising initiatives.

The research question for this study was thus stated as follows:

How do SGBs of self-managed public schools manage school (user) fees and other fundraising initiatives to facilitate the provision of quality education?

The following were sub-questions:

• What is the nature of effective and efficient school financial management in respect of school (user) fees and other fundraising initiatives?

• What are the perceptions of teachers and SMTs of the management of school fees and fundraising projects in self-managed public schools?

Aims of the Study

The general aim was to determine whether the SGBs of public schools manage school (user) fees and fundraising initiatives effectively and efficiently to facilitate the provision of quality education. In order to achieve this aim, the following objectives were formulated:

• To understand the nature of effective and efficient school financial management in respect of school (user) fees and other fundraising initiatives.

• To determine the perceptions of teachers and SMTs of the effective and efficient management of school fees and fundraising projects in self-managed public schools.

Financial management of fundraising initiatives and school fees

School financial management can be described as the performance of management actions (regulatory tasks) connected with the financial aspects of schools, with the aim of achieving effective education (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009). Financial management is a process with several activities: identification, measurement, accumulation, analyses, preparation, interpretation and communication of information. As mentioned previously, school managers with appropriate financial knowledge and skills are required to manage their schools' finances effectively and efficiently. Effectiveness implies school managers doing the right task, undertaking financial activities, yielding positive financial results and achieving school financial goals. Efficiency, often measureable, is about them doing things in an optimal way, for example doing it in the fastest or the least costly way. Efficiency is simply about school managers doing things right, that is, the ability to avoid wasting materials, energy, effort, money and time in doing something or in producing a desired result (WordReference.com, 2016).

To manage the finances effectively and efficiently, school managers ought to ensure that their role functions are clearly defined and the limits of their delegated authority are established; the budget reflects the school's prioritised educational objectives; they seek to achieve value for money and are subjected to regular monitoring; they establish sound internal and external financial control mechanisms to safeguard the reliability and accuracy of financial transactions; purchasing arrangements achieve best value for money; all financial records are meticulously maintained; and all monies collected are receipted, recorded and banked promptly (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009; Van Rooyen, 2012). To achieve the goals of the school, it is crucial that all financial activities undertaken by various individuals or committees are synchronised.

Systems theory (Banathy, 1991) was used as a conceptual framework to underpin this study. Systems theory gives primacy to the interconnectedness and interdependence of the elements in a system, as well as the evolutionary nature of a system (Banathy & Jenlink, 2004). The system of interest in this investigation was the DoE, SGBs, SMTs and principals. The central focus of systems theory is self-regulating systems, that is, systems that are self-managing and self-correcting through feedback. Self-regulating systems are found in local and global ecosystems, and in human learning processes. Duffy and Reigeluth (2008) explain that in order to improve the quality of teaching and learning, the circle goes around what we traditionally call a school system and everything outside the circle is known as the external environment. The SGBs, SMTs and principals, having a shared vision, influence the external environment (corporates and the broader community) to fund their organisations.

The discussion on self-managed schools is also subjected to a legal framework. The South African Schools Act of 1996 (as amended) and the National Norms and Standards for School Funding policy of 1998 (as amended) are two important Acts that underpin this study.

The Schools Act (Republic of South Africa, 1996) is aimed at the creation and management of a new national school system that provides uniformity in the organisation, governance and funding of schools. The National Norms and Standards for School Funding (NNSSF) policy (Republic of South Africa, 1998) provides a statutory basis for funding public schools, namely that schools serving poorer communities ought to receive far more funds from the state than schools serving better-off communities. In order to address equity in public school funding, the NNSSF policy (Republic of South Africa, 1998) requires that all public schools be ranked according to quintiles. Schools located in townships and rural areas are ranked as Quintiles 1 and 2, and most schools situated within affluent areas are ranked Quintiles 4 and 5. Some inner-city schools and schools serving middle class communities have been classified as Quintile 3. The current policy determines that poor schools, ranked Quintiles 1 and 2, and more recently Quintile 3 schools, be declared 'no-fee' schools. These schools receive a far higher state subsidy than their advantaged counterparts (Quintiles 4 and 5).

Despite the progressive NNSSF policy, affluent public schools have experienced dramatic changes in learner enrolment. Constitutional rights, the school fee-exemption policy and the advent of a new black middle class have resulted in mass migration of learners from township and rural schools to historically advantaged schools. According to Hofmeyr (2000), black parents realising the importance of quality education have enrolled their children at well-resourced affluent schools in suburbs. This is despite the high cost of school fees, uniforms and transportation.

Research reveals that decisions concerning school choice made by parents are mainly related to excellent learner performance and the school's achievement of sound education outcomes (Powers & Cookson, 1999; Teske & Schneider, 2001). These are ultimately linked to whether schools are well-resourced (physical as well as human). Acquiring substantial school funding secures essential or state-of-the-art resources for the provision of quality education. In South Africa, research conducted by Van der Berg (2006) revealed that fiscal resource inputs does have an effect on the educational outcomes. Levačić (2005), in her research, confirms that there is a causal link between resourcing and learner outcomes and makes the following arguments: changes in class size in the primary school from 40 to 50 may have a significant effect on teaching, and learning outcomes; conditions of classrooms (leaking and unusable classrooms) have a strong effect on reading and mathematics scores for middle school learners; and providing textbooks increases primary learners' attainment quite substantially.

For schools to improve learner performance and attain the desired educational outcomes, SGBs are required so as to prepare effective budgets. Mestry and Bisschoff (2009) describe the budget as the mission statement of the school expressed in monetary terms, and as a management tool, it contributes to the attainment of the school's goals and objectives. Resources, both financial and human, thus allow learners to fully participate in their education. Resources are required to address teacher-learner ratios, which influence class size; to provide learner support services in the form of counselling and support for those with special needs and literacy problems; and to uplift teacher morale in terms of the support they receive, their generally accepted poor salaries and their ever increasing workload. With sufficient financial resources, which are effectively and efficiently managed, schools are able to provide learners with access to textbooks and technologically advanced facilities (Blake & Mestry, 2014).

Schools that are financially self-managed are required to make substantial provision in their budget for services such as rates, water and electricity, and school repairs and maintenance. Funds are also set aside for educational excursions, safety and security of learners, hostel maintenance (where applicable), the cost of providing professional development programmes for teaching and nonteaching staff, the procurement of office equipment and software programmes, and the purchase and maintenance of vehicles.

Taking into account that public schools ranked as Quintiles 4 and 5 are marginally subsidised by the state, the SGBs are compelled to increase the level of funding through school fees, income generation and fundraising (Maruma, 2005). Parents are compelled to pay school (user) fees. To increase the schools' coffers, many of these schools tend to levy exorbitant fees to sup-lement state resources. The issue of school fees is controversial, and has been intensely debated in political and educational forums (Rechovsky, 2006). Some contend that school fees are used as a deterrent to deny poor learners access to well-resourced schools (see Roithmayr, 2002). However, Fleisch and Woolman (2004) repudiated Roith-mayr's claims. They were of the opinion that school fees do not constitute a significant barrier to access and defended the constitutionality of a school fee system. According to section 39 of the Schools Act, school fees may be determined and charged at a public school only if a resolution to do so has been adopted by a majority of parents attending the annual budget meeting. The resolution ought to provide for the amount of fees to be charged, and equitable criteria and procedures for the total, partial and conditional exemption of parents, who are unable to pay for school fees.

Progressive SGBs and principals are engaged in active entrepreneurial activities to raise additional funds through sponsorships and donations from the broader communities and corporate business (Blake & Mestry, 2014). Brauck-mann and Pashiardis (2011) assert that school managers should adopt the "Entrepreneurial Style", which entails the practice of involving parents and other external actors in school processes, acquiring resources for the smooth running of a school, building coalitions with external agents, and engaging in a market approach to leadership. Additional funds are acquired through creative means and the need to develop relationships with the business community, with regards to advertising and sponsorship, in an effort to earn their continued support (Blake & Mestry, 2014). Some examples of income generation include the sale of advertising space on school buildings, vehicles and sports kits. School premises could also be hired out during weekends for religious gatherings or large-scale events such as shows and exhibitions. Sports fields and apparatus could be a source of income after school hours or during the weekends if rented to external sports clubs and societies. Other possibilities of raising funds to supplement the government allocation include seeking out voluntary help, establishing school-business partnerships, recycling, and sponsorships of individual events, donations or the sale of donated items, and the hosting of community events (Blandford, 1997; Knight, 1993).

Research Methodology and Design

Having established a reference framework to locate the financial functions of role-players within the broader framework of South African public schools, the research methodology and design is now presented.

Schools, like other organisations, comprise of various hierarchical structures and systems such as the DoE, SGBs, SMTs, parents and teachers. Using systems theory as a point of departure, a quantitative study, comprising of a survey questionnaire consisting of four sections, was undertaken to investigate the views of teachers and SMT members of whether schools' finances were effectively and efficiently managed. The biographical details of respondents were required in Section A of the questionnaire. In Sections B, C and D the opinions of teachers and SMT members were extracted. Parts of Section B, which was concerned with the core components of equity in school funding, and Section D, which focused on the management of no-fee schools, fall outside the scope of this paper and are therefore not discussed. Section C comprised of twenty-six questions related to the management of school fees and fundraising initiatives of self-managed (fee-paying) schools. The items were based on key factors that had been prioritised during the literature review as having an influence on financial management in fee-paying schools. Teachers and SMT members were required to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements concerning the management of school fees and fundraising initiatives on a six-point Likert scale. The scale points ranged from 1 ("strongly disagree") to 6 ("strongly agree"). These closed-ended items were designed to garner the views of teachers and SMT members as to how effective their schools were funded and financially managed.

The measurement procedures and measurement instrument (questionnaire) for this study are considered reliable and valid. According to Babbie (2007), validity refers to the extent to which an empirical measure adequately reflects the real meaning of the concept under consideration. To ensure content validity, the items of the questionnaire relating to school funding were subjected to careful scrutiny by peers in the researchers' faculty and by the statistical services of the researchers' university. The reliability of this study, discussed below, has been demonstrated by the Cronbach's Alpha correlation coefficient.

Respondents were chosen from various post levels (teacher, heads of department, deputy principals and principals) of the teaching profession. The perception of teachers at various post levels, relative to the management of school finances, varied, and hence it was important to sample as wide a range of post levels as possible. Four hundred questionnaires were distributed to section 21 fee-paying schools located in the Johannesburg Central District of the Gauteng Province and collected personally by the researcher and research assistants. Purposive sampling was employed. Respondents were selected from fee-paying section 21 primary, secondary and special schools (quintiles 4 and 5) and were of both genders.

Three hundred and six questionnaires were received back from the section 21 fee-paying schools in useable form. This represented a 76.5% return rate. There were no foreseeable risks associated with the research and respondents were treated with the utmost respect in terms of their autonomy, basic rights, dignity, confidentiality and anonymity throughout the process. The question-naires were analysed by the statistical services of the university.

Findings and Discussion

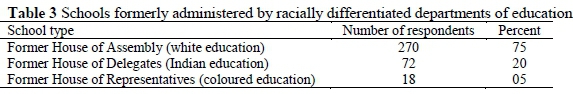

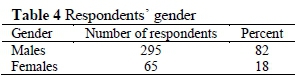

Tables 1 to 5 reflect the biographical details of respondents of self-managed schools that were elicited from section A of the questionnaire:

From this information it was established that the respondents provided a reasonably representative profile of urban schools in the Johannesburg District of Gauteng.

The non-biographical items (sections B, C and D) were subjected to exploratory factor analysis using the SPSS 15.0 programme (Norušis, 2009), with acceptable results, indicating that the items included in the scales represent the constructs appropriately. This statistical technique was used to estimate the construct validity of the questions that made up the scales. This technique conveyed the extent to which the questions seemed to measure the same concepts or variables (Glenn, 2010). The Cronbach's Alpha coefficient was used as an indicator to check the internal consistency of the items that make up the scale. According to Pallant (2005), the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of a scale should be above 0.7 for the scale to be considered reliable for the sample. In this study, the Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient varied between .978 and .966 for the various scales, which indicates that the inter-item reliability is acceptable and that the scales can be considered reliable for the sample.

The forty items in section B relating to both fee paying (N = 306) and non-fee paying (N = 332) were the same except for Item B4. Items 15, 18, 19 and 24 were reflected. The Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) for Item rB24 was <0.6, the communalities of Items B4 and rB15 were <0.2. Hence, these three items were removed from the factor analytic procedure, leaving 37 items. A first-order factor analytic procedure (PCA with Varimax rotation) indicated eight first-order factors. Only aspects relating to the financial management of fee-paying (self-managed) schools are discussed in this section.

It was established that most of the section 21 'fee-paying schools' group were, statistically, significantly more positive in their perceptions than the 'no-fee schools' group. The effect size was moderate (r = 0.4) and this also indicated the practical significance that the 'fee-paying schools' group attached to the effective and efficient management of funds in respect of school fees and fundraising activities. The majority of respondents from 'fee-paying schools' were not opposed to the state providing more funds to schools that were located in townships and rural areas (quintiles 1, 2 and 3). They believed that equity in school funding had to be addressed, and that the bulk of the allocated funds ought to be distributed to the historically disadvantaged schools.

Fee-paying schools were allocated less money for resources by the state, but SGBs supplemented these funds by levying school (user) fees to parents, securing donations and sponsorships from donors and sponsors, and organising and implementing fundraising initiatives. Systems theory emphasises collaboration among stakeholder systems in order to give importance to the interconnectedness and interdependence of all the elements in a school system. Respondents confirmed that parents who paid school fees were invariably bound to be more involved in school affairs, when it came to ensuring that their children got the best value for the additional money they provided. In general, it was found that most effective SGBs plan and implement well-organised fundraising events. Most of the respondents acknowledged that their SGBs, SMTs and teachers invested a great deal of time and energy to supplement state funding through several fundraising projects. This enabled the schools to procure state-of-the-art physical resources and to employ additional teachers above the post-provisioning norm determined by the DoE. They were aware that the limited state funding is earmarked only for topping up LTSM, part payment of services rendered to schools and to some extent maintaining school property. It was evident to them that the state funding was insufficient to address the procurement of additional high-tech physical and other important resources needed for teaching and learning. Additional funding enabled schools to have physical resources that were in good working condition, well-resourced libraries and laboratories, well-maintained buildings and small classes. These all undoubtedly contribute to the provision of quality education. It was also implied that most SGBs and principals had adequate knowledge and skills to effectively manage the schools' finances.

The 26 items involved with fee-paying schools in Section C were subjected to a factor analytic procedure. The Kaiser Meyer Olkin value for items C15B, C19B, C20B and C24B were all less than 0.6 and were removed from the procedure. Three first-order factors resulted, which explained 58.72% of the variance present. When these three first-order factors were subjected to a second-order PCA procedure only one factor resulted, which explained 47.06% of the variance present. It contained 22 items, and had a Cronbach Reliability Coefficient of 0.870 and was named 'The effective implementation management of the delegated financial functions'. The mean score of 3.66 and the median of 3.68 indicate that the respondents of fee-paying schools tended to partially agree with the effective implementation management of the delegated financial functions'. The following three factors are discussed.

Factor One: The SGBs Compliance with the Delegated Financial Functions

The respondents agreed that most of the SGBs complied with the delegated functions stipulated in the Schools Act, the Employment for Educators Act and the NNSSF policy. Most of the respondents were unanimous that the SGBs developed and implemented well-formulated finance policies and were of the opinion that their SGBs managed the school fees and fundraising projects effectively and efficiently. The SGBs and SMTs ensured that good software programmes were utilised in maintaining proper accounting records and that all incoming funds and expenditure incurred were meticulously recorded and managed according to the prescriptions of the schools' budgets. Additional finance officers were employed to ensure that efficient records of school fees received were maintained. Parents received statements that were regularly sent out by schools informing them of the amounts paid and/or outstanding in respect of school fees. Some self-managed schools fully applied the DoE's school fee exemption policy. However, according to the OECD report (2008), several instances have been noted where SGBs have misused their power to set and enforce high school fees in order to restrict admissions, or to exclude learners whose parents are unable to pay fees on time. SGBs have not always publicised the parents' right to apply for a discount or a school fee exemption, and they have failed to provide assistance to parents who find it difficult to engage in complex application and appeal procedures. Moreover, many parents were unaware of the automatic school fee exemptions that existed for certain learners, such as orphans or those receiving a Child Support Grant. SGBs could certainly do more to publicise and actively promote parents' and learners' rights under the law and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It appeared that many provincial departments of education have reneged on the policy requiring them to reimburse schools with 25% of the fee exemptions granted to learners.

The findings of this study align with the focus of systems theory i.e. that most schools were selfregulating systems, that is, that they were self-managing and self-correcting through feedback. The DoE, parents, and the broader community usually received regular feedback about the financial position of the schools. The respondents agreed that SGBs of self-managed schools had well-constructed fundraising programmes and all stakeholders were timeously informed of each fundraising event. Data suggest that these stakeholders have the attitudes and abilities to be entrepreneurial (Brauckmann & Pashiardis, 2011). It appears that SGBs and principals in most schools explore many possibilities to secure funds and exploit financial opportunities. It was implied that SMTs and teachers ought to see fundraising as part of their responsibility. According to Blake and Mestry (2014), fundraising is both varied and ingenious with regards to methods and ideas. SGBs and principals ought to tap into the creativity of the school and all its stakeholders. SGBs and principals should see entrepreneurship as part of their duties and responsibilities in terms of supplementing the provincial departments of education's funds in delivering a better quality of education for their learners.

Factor Two: Stakeholder Involvement in Fundraising Initiatives

Respondents were of the opinion that there existed a lack of parental and community support for fundraising initiatives. They believed that parents considered fundraising to be the sole responsibility of SMTs, teachers and non-teaching staff. Thus, a lack of stakeholder collaboration prevailed in many schools. It was also implied by respondents that many parents, in addition to the school fees, are expected to contribute financially to all fundraising initiatives. Parents are reluctant to contribute every time fundraising events are undertaken by schools.

The DoE, SGBs, principals and SMTs should have a clear understanding of their functions as stipulated in various legislation and regulations. This can be achieved if authentic collaboration among relevant stakeholders exists. Although the Schools Act states that professional management is the domain of the SMTs and principals and governance the responsibility of SGBs, collegiality and collaboration between management and governance should be encouraged. The DoE should ensure that training is provided to the respective role-players in the field of financial management resulting in school finances being effectively and efficiently managed. In keeping with systems theory, it is important that SGBs and principals begin to engage with staff and parents to develop creative fundraising opportunities and to search for solutions to financial problems. They should see this as a joint venture: learners and parents benefit because there are steps taken to provide quality education and teachers and SMTs have resources that will facilitate their effective teaching. SGBs and principals should be the driving force to get parents and the business community more involved in fundraising activities. This necessitates a collegial management style to bring this about.

Most of the respondents who belong to schools' with more than 1,000 learners agreed to a statistically significantly greater extent with the effective management of funds in respect of school-fees and fundraising initiatives than did respondents in schools with less than 1,000 learners. Fee-paying schools tend towards agreeing with the 'effective implementation management of the delegated financial functions' factor because parents of most of these schools pay their school fees, which enabled their SGBs to procure physical resources and employ additional teachers. This, in contrast to smaller schools where school fees and fundraising are not substantial. Having more learners mean that more school fees are received and more parents support fundraising projects. Respondents were of the opinion that although active participation from parents were not forthcoming, principals and SGBs were effective in raising substantial sums of money through school fees and fundraising ventures. This enabled schools to purchase appropriate educational aids and employ more teachers so that effective teaching and learning can take place in their schools.

Factor Three: The Process of Effective Budgeting

Respondents from fee-paying primary schools agreed to a statistically significantly larger extent with the effective management than do fee-paying respondents from secondary schools. In primary schools, the income and expenditure is not as extensive as in secondary schools. The postprovisioning norm of secondary schools is greater than that of primary schools, because more subjects are offered to learners. The cost of employing additional teachers, providing extra-curricular activities, procuring more specialised textbooks and high-tech equipment, and upgrading the school library with national and international books, are all factors that demand the SGBs, SMTs and teachers put more effort into school funding. These factors make respondents from secondary schools less positive about the effective management of school fees and fundraising than their primary school counterparts.

Most of the respondents of self-managed schools agreed that their SGBs drew up effective budgets and that these were successfully implemented. The SGBs follow a similar process, by decentralising the drafting of the budget. They request heads of department, programme coordinators, teams and non-teaching staff to submit their resource needs to them. They prioritise and, using a zero-based budgeting approach, draw up the master budget. From the projected expenditure, they determine the amount of school fees parents have to pay and project what funds need be generated from fundraising projects. This budget has to be approved by the parents at an annual budget meeting. Respondents implied that the parents' attendance at budget meetings was satisfactory. Respondents of some schools indicated that not all fundraising projects were successfully implemented, and perhaps, parents were not fully cooperative. Thus, some schools were unable to achieve the goals they set out for a particular financial year.

Respondents also alluded to the fact that due to the increased financial responsibilities of finance officers in self-managed schools, SGBs have invested in highly sophisticated technology, such as software programmes, that ensure the monitoring and controlling of budgets and facilitate the effect-tive management of school fees and fundraising activities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper aimed to determine the perceptions of SMTs and teachers as to whether self-managed schools manage their finances effectively and efficiently. The government's agenda of addressing equity and social justice in education has resulted in affluent public schools (Quintiles 4 and 5) receiving far less in subsidies than was received by poorer schools. This has posed serious funding challenges. To be competitive and market-oriented, attract the best learners and ensure that effective teaching and learning takes place, SGBs are required to devise ways to supplement state funding. Many schools resort to levying exorbitant school (user) fees, thus making access for poor learners impossible, and disregarding school fee exemption regulations. To intensify their fundraising endeavours, progressive SGBs must find more creative and ground-breaking ways to do so.

The three factors that emerged from this study, namely, SGBs' compliance with delegated financial functions; stakeholder involvement in fundraising initiatives; and the process of effective budgeting, emphasises the pertinent role played by SGBs in managing a school's finances effectively and efficiently. This empirical study suggests that SGBs and principals ought to have expert financial knowledge and skills, such as budgeting, organising, monitoring and control, to lead their schools in the attainment of excellent learner performance and educational outcomes. SGBs and principals need to tap into the creativity in their schools and collaborate with all stakeholders. They ought to embrace entrepreneurial qualities and begin consciously using them in adopting entrepreneurial practices. They should see entrepreneurship as part of their responsibility to supplement the DoE's allocation of funds, and to deliver a better quality of education.

It is recommended that the DoE strive to convert all public schools, irrespective of their quintile status, to become self-managed. They should provide intensive training and development for stakeholders (parents, teachers, SMTs and the broader community) and empower them to make good financial decisions for their schools. The topics for training should include, among others, the planning and implementing of effective budgets and fundraising projects, understanding school financial statements and reporting on a school's finances to stakeholders. To achieve these objectives, the DoE ought to consider securing the services of external service providers who have specialised knowledge of school financial management.

References

Anderson L & Lumby J (eds.) 2005. Managing finance and external relations in South African schools. London, UK: Commonwealth Secretariat. [ Links ]

Babbie E 2007. The practice of social research (11th ed). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Banathy BH 1991. Systems design of education: A journey to create the future. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Banathy BH & Jenlink PM 2004. Systems inquiry and its application in education. In DH Jonassen (ed). Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Bloomington, IN: Association for Educational Communications and Technology. [ Links ]

Bisschoff T & Thurlow M 2005. Resources for schooling. In L Anderson & J Lumby (eds). Managing finance and external relations in South African schools. London, UK: Commonwealth Secretariat. [ Links ]

Blake B & Mestry R 2014. The changing dimensions of the finances on urban schools: An entrepreneurial approach for principals. Education as Change, 18(1):163-178. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2013.847017 [ Links ]

Blandford S 1997. Resource management in schools: Effective and practical strategies for the self-managing school. London, UK: Pitman Publishing. [ Links ]

Botha RJ (ed.) 2012. Financial management and leadership in schools. Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson. [ Links ]

Brauckmann S & Pashiardis P 2011. A validation study of the leadership styles of a holistic leadership theoretical framework. International Journal of Educational Management, 25(1):11-32. doi: 10.1108/09513541111100099 [ Links ]

Brauckmann S & Schwarz A 2014. Autonomous leadership and a centralised school system. An odd couple? Empirical insights from Cyprus. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(7):823-841. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-08-2013-0124 [ Links ]

Bush T & Heystek J 2003. School governance in the New South Africa. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 33(2):127-138. doi: 10.1080/0305792032000070084 [ Links ]

Deming WE 1994. The new economies for industry, government, education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Department of Education, South Africa 1996. Changing management to manage change in education: Report of the Task Team on Education Management Development. Pretoria: Department of Education, South Africa. Available at https://edulibpretoria.files.wordpress.com/2008/01/changingmanagement.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2016. [ Links ]

Drury DW 1999. Reinventing school-based management: A school board guide to school-based improvement. Alexandria, VA: National School Boards Association. [ Links ]

Duffy FM & Reigeluth CM 2008. The school system transformation (SST) protocol. Educational Technology, 48(4):41-49. [ Links ]

Fiske EB & Ladd HF 2005. Racial equality in education: How far has South Africa come? Working papers series SAN05-03. Durham, NC: Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University. Available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED493386.pdf. Accessed 19 January 2016. [ Links ]

Fleisch B & Woolman S 2004. On the constitutionality of school fees: A reply to Roithmayr. Perspectives in Education, 22(1):111-123. [ Links ]

Gann N 1998. Improving school governance: How governors make better schools. London, UK: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Glatter R, Mulford B & Shuttleworth D 2003. Governance, management and leadership. In Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (ed). Networks of innovation: Towards new models for managing schools and systems. Paris, France: OECD. Available at http://www.oecd.org/site/schoolingfortomorrowknowledgebase/themes/ innovation/41283811.pdf. Accessed 7 May 2016. [ Links ]

Glenn JC 2010. Handbook of research methods. New Delhi, India: Oxford. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr J 2000. The emerging school landscape in postapartheid South Africa. Speech presented for the Independent Schools Association of South Africa, 30 March. Available at http://stbweb01.stb.sun.ac.za/if/Taakgroepe/iptg/hofmeyr.pdf. Accessed 9 August 2015. [ Links ]

Karlsson J 2002. The role of democratic governing bodies in South African schools. Comparative Education, 38(3):327-336. doi: 10.1080/0305006022000014188 [ Links ]

Knight B 1993. Financial management for schools: The thinking manager's guide. Oxford, UK: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Levačić R 2005. The resourcing puzzle: The difficulties of establishing causal links between resourcing and student outcomes. Inaugural professorial lecture. London, UK: Institute of Education, University of London. [ Links ]

Levačić R & Vignoles A 2002. Researching the links between school resources and student outcomes in the UK: A review of issues and evidence. Education Economics, 10(3):313-331. doi: 10.1080/09645290210127534 [ Links ]

Marishane RN 2003. Decentralisation of financial control: An empowerment strategy for school-based management. Unpublished DEd thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Marishane RN & Botha RJ 2004. Empowering school-based management through decentralised financial control. Africa Education Review, 1(1):95-112. doi: 10.1080/18146620408566272 [ Links ]

Maruma MA 2005. The role of the school governing body in managing fundraising for public primary schools in disadvantaged communities. Unpublished MEd dissertation. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available at https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/handle/10210/1151. Accessed 7 May 2016. [ Links ]

Mestry R 2004. Financial accountability: the principal or the school governing body? South African Journal of Education, 24(2): 126-132. Available at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/view/24977/20661. Accessed 7 May 2016. [ Links ]

Mestry R 2006. The functions of school governing bodies in managing school finances. South African Journal of Education, 26(1):27-38. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/67/63. Accessed 7 May 2016. [ Links ]

Mestry R & Bisschoff TC 2009. School financial management explained (3rd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Pearson. [ Links ]

Motala S 2011. Children's silent exclusion. Mail & Guardian, 22 July. Available at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-07-22-childrens-silent-exclusion. Accessed 8 May 2016. [ Links ]

Mtshali N 2012. R4.6m probe into mismanagement at public schools. Star, 8 March. Available at http://www.iol.co.za/the-star/r46m-probe-into-mismanagement-at-public-schools-1251497. Accessed 27 September 2015. [ Links ]

Norušis M 2009. SPSS 16.0 guide to data analysis (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2008. Reviews of national policies for education: South Africa. Paris, France: OECD. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Reviews%20of%20National %20Policies%20for%20Education%20-%20South%20Africa,%2016%20February%202009.pdf?ver=2011-01-18-113926-550. Accessed 24 February 2014. [ Links ]

Pallant J 2005. SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows (Version 12). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. Available at http://www.academia.dk/BiologiskAntropologi/Epidemiologi/PDF/SPSS_Survival_Manual_ Ver12.pdf . Accessed 8 May 2016. [ Links ]

Parker K & Leithwood K 2000. School councils' influence on school and classroom practice. Peabody Journal of Education, 75(4):37-65. doi: 10.1207/S15327930PJE7504_3 [ Links ]

Phaladi B 2015. Glenvista 'fraudsters' face criminal charges. Citizen, 11 August. Available at http://citizen.co.za/445459/glenvista-fraudsters-face-criminal-charges/. Accessed 8 May 2016. [ Links ]

Powers JM & Cookson PW Jr 1999. The politics of school choice research: Fact, fiction, and statistics. Educational Policy, 13(1):104-122. doi: 10.1177/0895904899131009 [ Links ]

Rechovsky A 2006. Financing schools in the new South Africa. Comparative Education Review, 50(1):21- 45. doi: 10.1086/498327 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. South African Schools Act, 1996 (Act No. 84 of 1996). Government Gazette, No. 1867. 15 November. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1998. National Norms and Standards for School Funding. Government Gazette, No. 19347. 12 October. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1999. Public Finance Management Act No. 1 of1999. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Roithmayr D 2002. The constitutionality of school fees in public education. Education Rights Project. Centre for Applied Legal Studies. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand. Issue Paper. [ Links ]

Teske P & Schneider M 2001. What research can tell policymakers about school choice. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(4):609-631. doi: 10.1002/pam.1020 [ Links ]

Theodorou T & Pashiardis P 2015. Exploring partial school autonomy: What does it mean for the Cypriot school of the future? Educational Management Administration & Leadership. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1741143214559227 [ Links ]

Tsotetsi S, Van Wyk N & Lemmer E 2008. The experience of and need for training of school governors in rural schools in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 28(3):385-400. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/181/122. Accessed 29 April 2016. [ Links ]

Van der Berg S 2006. The targeting of public spending on school education, 1995 and 2000. Perspectives in Education, 24(2):49-63. [ Links ]

Van Deventer I & Kruger AG 2003. An educator's guide to school management skills. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Van Rooyen J 2012. Financial management in education in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Van Wyk N 2007. The rights and roles of parents on school governing bodies in South Africa. International Journal about Parents in Education, 1(0):132-139. Available at http://www.ernape.net/ejournal/index.php/IJPE/article/viewFile/34/24. Accessed 29 April 2016. [ Links ]

WordReference.com 2016. Effectively vs efficiently. Available at http://forum.wordreference.com/threads/effectively-vs-efficiently.1650818/. Accessed 12 January 2016. [ Links ]

Xaba M & Ngubane D 2010. Financial accountability at schools: challenges and implications. Journal of Education, 50:139-159. [ Links ]