Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.36 n.2 Pretoria May. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n2a1132

A pedagogical approach to socially just relations in a Grade 11 Economics class

Zayd Waghid

Department of Further Education, Faculty of Education, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. waghidz@cput.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Post-apartheid schooling in South Africa is challenged with the task of contributing towards social justice, as has been evident from the emergence of a plethora of education policies following the promulgation of the South African Schools Act in 1996. One of the most significant ways in which social justice can be cultivated in schools, especially where exclusion and marginalisation have been in ascendancy for decades, is through improved pedagogical activities, which receive focus in this article. The article focuses on investigating how the learning goals for Grade 11 Economics with the aid of an educational technology, in particular Facebook, engender opportunities for socially just relations in the classroom. The researcher is concerned with how these learning goals are related to three underlying aspects of Economics education, namely sustainable development, equity (including equality) and economic development, and how they may or may not engender opportunities for social justice. Critical discourse analysis is the research approach used to analyse learners' comments on Facebook in relation to their understandings of three films. It was found that it is possible to teach and learn education for social justice in the classroom. Learners treated one another equally; enacted their pedagogical relations equitably; and learnt to become economically aware of their society's developmental needs. Thus, it is recommended that education for social justice be cultivated in school classrooms through the use of Facebook.

Keywords: Desert (Reward); Economic Development; Education; Equality; Equity, Learning; Need; Social Justice; Sustainable Development (SD); Teaching

Introduction

South Africa, as an emerging economy, has considerable potential, with an extensive public services sector, improvement in health indicators, falling crime rates, and favourable demographic trends, with public finances in better shape than those of many OECD countries (OECD, 2013). However, despite the economy's prospective future, the high level of inequality in all spheres of the economy is considered a major challenge to the South African government (OECD, 2013). Income inequality remains extremely high, educational outcomes are below international standards, and hugely uneven, with corruption, bureaucracy and service delivery failure that have permeated the economy post-1994 (OECD, 2013).

In contrast, international trends seem to show that rising income inequality is not particularly unique to South Africa, with most OECD countries permeated by an unjust disparity of wealth, where the Gini co-efficient has increased on average from 0.28 in the mid-1980s to 0.31 in the late 2000s, even in a country like China, where poverty has been reduced (Netshitenzhe, 2014:1). More specifically, this article confirms international trends of cultivating an education for social justice in classroom relations in the following ways: first, it encourages learners to participate actively with educators on an equal basis on the premise that their relations are democratic, inclusive and engaging and will bring about sustainable change in the classroom and society (Bell, 1997); second, it shows that critical self-reflective teaching is an instance of education for social justice, where for hooks (2003), educators work as deliberative agents, consistently attempting to undermine dominance and privilege (in relation to societal inequity), and to critique their practice in relations with their colleagues. In other words, education for social justice involves the practice of autonomous freedom to prevent feelings of powerlessness on the part of educators, who are required to function as deliberative agents in their relations with others, including learners. Third, an education for social justice involves the cultivation of equal classroom relations amongst educators and learners, by being reflective, empowering and committed to social change.

Building on the international scholarship on education for social justice, the researcher has found that working towards education for social justice in an Economics Grade 11 classroom is a way of enacting change with learners, rather than always doing things for them. In other words, through the teaching of the Economics Grade 11 learning goals, both the learners and researcher became acutely aware that the autonomous self is a site for pedagogical and social change that involves critically interrogating one's own understanding of social injustices, and keeping one's mind open to other possibilities. Moreover, the learners and researcher also engaged in deliberative, inclusive and equal relations with one another. Thus, learners became agents of change by disrupting forms of social oppression and inequity such as racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, gender oppression and ethno-religious oppression, and seeking to build just and non-discriminatory communities [as is evident from the learners' comments on the Facebook screenshots].

The South African government's economic policy, the National Development Plan (NDP), seeks to empower all citizens of South Africa who have the capabilities to grasp the ever-broadening opportunities available, and to change the life chances of millions of people in South Africa, particularly the youth, who remain stunted by the legacy of apartheid (National Planning Commission, Republic of South Africa, 2011:1). South Africa has the means, the goodwill, the people and the resources to eliminate poverty and inequity. In South African education, White Paper 6 on Inclusive Education (Department of Education, 2001), describes the government's intent to implement inclusive education at all levels in the education system by 2020, reducing barriers to learning, and facilitating the inclusion of vulnerable learners (OECD, 2008:40). Inclusivity and democracy are crucial if social justice is to be achieved in South Africa, particularly in an international context, if we are to address barriers to learning that exist in today's global society.

It is here that the researcher situates himself as an educator in a local and historically disadvantaged public high school, wanting to make a contribution through improving classroom pedagogy along the lines of enhanced inclusivity and democratic relations with learners, as actions that can possibly advance social justice at a microas well as macro-level. Education for social justice has been critiqued for being too myopic, and failing to attend to learning goals of education systems (Sleeter, 2001). Likewise, it is recognised that there is a dearth of rigorous empirical investigations by means of which to achieve learning goals (Zeichner, 2005). In this article, the researcher attempts to be responsive to such critiques by making a case for the examination of teaching and learning in the classroom in relation to education for social justice. The researcher contends that cultivating education for social justice in school classrooms in South Africa has the potential to evoke in learners the capacities to become autonomous, critical and deliberative, which in turn, would orientate them towards becoming more intent on harnessing equal, equitable and just pedagogical classrooms relations. This brings the researcher to a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of education for social justice.

Literature Review

Education and social justice

Jane Roland Martin's theory of education holds that education only occurs if there is an encounter between an individual and a culture in which one or more of the individual's capacities, and one or more items of a culture's stock, become yoked together (or attached) (Martin, 2013:17). In essence, whenever capacities and stock meet and become attached to one another, then education occurs. In agreement with such a view of education, the researcher contends that education for social justice should always be considered as an encounter amongst individuals, groups and/or other entities. This means that individuals and others bring to the encounter their capacities (for learning) and cultural understandings and, in turn, together shape the particular encounter. And, when the aim of education is to achieve social justice, the capacities and cultural stock of individuals invariably ought to be geared towards attaining social justice.

International trends suggest that education for social justice is considered an ambiguous and under-theorised concept. It has been considered as a distributive notion of justice (Fraser & Honneth, 2003); an enhancement of learning and life chances by contesting the inequities of school and society (Cochran-Smith, 2004); and the recognition of significant disparities in the distribution of educational opportunities, resources, and academic achievement on the part of educators (Michelli & Keiser, 2005). In this article, the researcher positions himself as an educator for social justice, who considers the purposes of teaching and learning as opportunities to enact change with learners in a Grade 11 Economics classroom.

Social justice is regarded as an aspect of distributive justice, where the latter, according to the philosopher Aristotle, is concerned with the fair distribution of benefits among the members of various associations (Miller, 2003:2). Such an understanding of distributive justice has as its pioneer the famous liberal theorist John Rawls (1971), who, in his monumental work, A Theory of Justice (Rawls, 1971:78) explains justice in terms of two principles that ought to guide the distribution of primary goods, including wealth and income. The principles advocated by Rawls are the following: First Principle (Liberty principle) -Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all. In other words, all people have access to their basic liberties, which include freedom of speech, political freedom and access to property, and freedom from arbitrary arrest; and Second Principle (Difference principle) - Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged such that they are both (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, consistent with the just savings principle, and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity (Rawls, 1971:266).

Central to any theory of justice will be an account of the basic rights of citizens, such as freedom of speech and movement, in terms of which people are empowered to deliberate and express their feelings with others in debates and discussions pertaining to particular topics at hand. Also, one of the most contested and inextricable issues arising in debates about freedom is whether and when a lack of resources constitutes a constraint on freedom (Miller, 2003:13). The issue of school fees in South Africa poses a great challenge for many learners from disadvantaged backgrounds, and thus begs us to question how freedom could in fact be attained. Iris Young's rendition of social justice centrally requires "the elimination of institutionalised domination and oppression", where distributive issues ought to be tackled from this perspective (Miller, 2003:15). Power needs to be decentralised so as to allow people to make their own decisions in the pursuit of social justice. According to Miller, for society to be just, it must comply with the principles of need, desert, and equality, whereby institutional structures must ensure that an adequate share of social resources is set aside for individuals on the basis of need (Miller, 2003:247). Social justice thus requires that the allocating agencies be set up in such a way that vital needs such as food, medical resources and housing become the criteria for distributing the various resources for each of the specific needs (Miller, 2003:247). Also, a main concern social justice attends to is 'economic desert', a term borrowed from David Miller, which refers to the way in which people are financially rewarded for the work that they perform, to encompass productive activities such as innovation, management and labour (Miller, 2003:248). The reward for performance should serve as an incentive for the working class to improve productivity and efficiency. However, we find that certain rich and affluent schools are able to reward their teachers, based on their academic performance, and in terms of extramural activities, whereas schools in more disadvantaged communities are not able to offer the same reward, due to a lack of resources. This begs the question as to how social justice can be achieved in South Africa, in terms of the economic desert to be found in the considerable lack of resources available to poor, disadvantaged schools when compared to affluent schools. A third element of social justice is equality, in terms of which democratic citizens ought to be treated equally so that they can enjoy their legal, political and social rights (Miller, 2003:250).

International trends in teaching for social justice have considerably favoured the academic performance of learners at schools. A study conducted in the United States measured the academic performance of 185 Latino Eighth Graders, where it was concluded that learners who embraced their culture, as well as barriers of discrimination, perform better academically than the other immigrant students who failed to do so (Altschul, Oyserman & Bybee, 2008 in Sleeter, 2013:3). However, this article did not look at the impact that teaching for social justice has on the academic performance of learners, but rather looked at three films in relation to economics education, and its implications for teaching and learning between the learners and the researcher. Instead of focusing on what educators can do for learners, as the researcher I focused on what educators and learners can do with one another. Inasmuch as the aforementioned theory on social justice emphasises the importance of gaining access to resources, I argue from the premise that the most promising resource that learners and educators have at their disposal is the capacity to engage with one another in an encounter. Through their pedagogical encounters learners and educators have the potential to act justly, that is, they engage with one another equally, equitably and deliberatively without excluding one another from their forms of human engagement.

Measures required to deal with inequality include affording people their need through sustainable development, their economic desert and quality education - aspects of social justice. What makes this article apposite in this context is that through cultivating pedagogical encounters in the classroom one would foster socially just relations in the classroom by preparing learners for their future roles in society through critical selfreflection and deliberation amongst one another.

Put differently, the research in this article contributes to an exposition and cultivation of an education for social justice in the following ways: First, learners can be initiated into a discourse of social justice education in school classrooms, where they are taught to become autonomous and critical beings. Second, learners and educators can engage deliberatively in order to address important political, economic, societal and environmental challenges along the lines of defensible understandings of SD, economic development and equity. Third, learners can become disruptive agents of change to enact transformation in and beyond the classroom. The afore-mentioned aspects in some ways confirm and also extend international trends in pedagogical relations amongst educators and learners aspiring to engender education for social justice in classrooms.

During the apartheid past, learners and educators participated in pedagogical relations without necessarily harnessing their encounters along the lines of equality, equity and deliberation. The afore-mentioned aspects of justice were curtailed to the extent that learners were not encouraged to question and challenge. Nowadays, although the new curricular reforms emphasise the importance of critical learning, my own engagement with school reform has revealed that critical learning remains in an embryonic phase, where it is not entirely elusive. Hence I aspired to engender learning opportunities in the classrooms that can effect the realisation of socially just relations. This leads to a discussion of methodology.

Methodology

Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis, as a qualitative research design, allows discourse analysts to investigate the use of language in context, and is concerned more with what writers or speakers do, than with the formal relationships among sentences or propositions (Alba-Juez, 2009:16; Wodak, 2011:44). The approach has a social dimension, and for many analysts, it is a method for determining how language "gets recruited on site to enact specific social activities and social identities" (Gee, 1999 in Alba-Juez, 2009: 11).

In the context of this study and more specifically 'discourse' encompasses not only written and spoken language such as policy documents that is the education policy texts, and transcripts of learner interviews, but also visual images in the form of films on the subject of education for social justice. However, within critical discourse analysis (as in discourse analysis in general), there is a tendency to analyse pictures and films as if they were linguistic texts (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002:61). Thus, the data sets in this study comprise multi-modal texts - that is, texts which make use of different semiotic systems such as written language (policy texts), visual images (Facebook screenshots) and/or sound.

For critical discourse analysts, discourse is a form of social practice. As a social practice, discourse is in a dialectical relationship with other social dimensions. It not only contributes to the shaping and reshaping of social structures, but also reflects them (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002:61). In other words, critical discourse analysis (CDA) "engages in concrete, linguistic textual analysis of language use in social interaction [...] [with the aim] of contributing to social change along the lines of more equal power relations in communication processes and society in general" (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002:64).

In this article, the preference given to CDA is stimulated by the concern to engender socially just pedagogical relations in the classroom. By analysing the comments of learners as they engage in pedagogical encounters, I have done so critically, as I endeavour to construct meanings of the learners' comments in relation to my own 'presence' in the encounter.

Data Source and Sample

Considering the rationale of this study to discover how learners acquired some of the learning goals of the South African Department of Basic Education's (DoE) Grade 11 Economics curriculum, including how they were initiated into an education for social justice - focusing on need, economic desert and equality, the objective was to analyse their discussions amongst themselves on a Facebook group site. The purpose of the Facebook group site was to afford learners the opportunity to engage and deliberate with one another as a means of preparing them for pedagogical activity. In order to facilitate the learners' pedagogical activities, the researcher introduced learners to the following three films:

An Inconvenient Truth

An Inconvenient Truth is a defence of environmental sustainability on the part of the narrator, Al Gore, who invokes both personal and universal ecological memories. Beginning with shots of a river, and photographs of Earth shot in outer space from the Apollo missions, the narrator introduces what can be argued to be the most powerful rhetorical narrative behind the documentary's success, namely environmental nostalgia. Gore uses the rhetoric of nostalgia to illustrate the problem of global warming to which humans contribute, which causes the rise in temperatures on Earth, with destructive environmental and social consequences.

Into the Wild

Into the Wild is a true story of Christopher McCandless, a bright young American college graduate who shocked his parents by sending his $24,000 law school fund to Oxfam, abandoning all his possessions and hiking into the wilderness in search of a radical re-engagement with nature, unenticed by money and unfettered by the prospect of a career. In 1992, at the age of 24, McCandless was found dead in the Alaskan backwoods in an abandoned bus he was using as shelter. The film depicts a storyline of sadness that captivates the attention of the audience with the main argument that to be human, such as to live one's life without an preoccupation with gratuitous wealth that contributes to societal inequity, is to be liberated from that which causes so much injustice, namely greed, corruption and materialistic enslavement.

The Gods Must Be Crazy

The argument offered by the producer of the film Jamie Uys, is that competition and greed often result in confrontation and exploitation - a matter of social injustice, making its way into the relations amongst people, because their right to economic equity is denied. If the producer intended to offer a solution to the problem of a lack of integration exacerbated by exclusion and ridicule of the Other, his comedy portraying the San (Bushmen) as 'backward' certainly does little for inclusion and hospitality towards what is for him the Other. The misrepresentation of the San as 'noble savages' that require assimilation into a more 'civilised' world, is a persistent problem identified with discourses of integration.

I analysed three sets of Facebook screenshots on which the comments of learners had been posted. These analyses relate to the views of learners in relation to the three international films mentioned above. These films are linked specifically to the topics of SD, equity, and economic development, respectively.

Data on the Grade 11 Economics learners was compiled using an assignment on education for social justice related to the themes of SD, equity and economic development that was completed by the learners. The purpose of the assignment was twofold: first, the assignment served to establish how three films (as pedagogical resources) contributed to the learners' understanding of the three underlying themes; and second, it served as a means to ascertain the learners' understanding of socially just relations in the classroom.

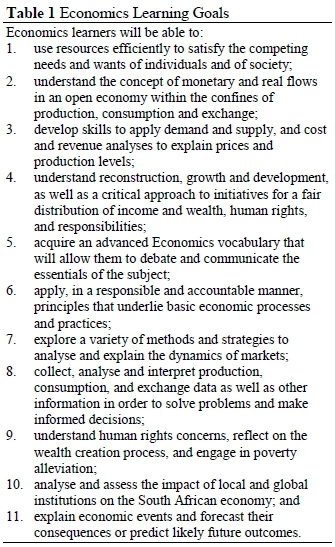

The results of the assignment (from which the population sample was derived) indicated that there were fifteen females and ten males (twenty-five learners in total), aged 16 and 17 years of age, in the class. The sample selection was made on the basis of recruiting participants who, by their own subject selection of economics, indicated their preference for contributing to the development of education for social justice in the broader South African society. Moreover, I selected this class because all learners showed willing interest in establishing pedagogical relations with the researcher through Facebook. The majority of the learners lived in the southern suburbs of Cape Town in South Africa, mostly from middle-class families residing in historically disadvantaged communities. The successful completion of the assignment depended on the learners' ability to access the internet, and through the assignment, I was able to ascertain the ways in which they did so. All twenty-five learners owned smartphones, which totalled twenty BlackBerrys, and five Samsung Galaxy smartphones or iPhones. Most of the learners opted for the BlackBerry smartphone due to the cost-effective internet access provided by the various network providers. Also, all of the learners had internet at school by means of which to access the Facebook group site, and the learners established individual groups with their peers in order to answer the questions that the researcher posed on the Facebook site. Despite all twenty-five learners emanating from low to middle income families, the potential was always there for them to be subjected to pedagogical exclusion and marginalisation if any of the learners involved may have wanted to dominate discussions. Consequently, the analyses of the films were also intended to ascertain the extent of the discrepancy between the frequency of individual learner input. Moreover, the use of films was aimed at supporting the achievement of learning goals on the part of learners. The following table offers a summary of the learning goals for the Grade 11 Economics curriculum, which the researcher extracted from the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement document for Economics, 2011:

Before presenting an analysis of the three films, I offer some theoretical exposition of SD, equity and economic development. First, education for sustainable development (ESD) has been depicted as the cultivation of "all aspects of public awareness, education and training provided to create or enhance an understanding of the linkages among the issues for SD and to develop the knowledge, skills, perspectives and values that will empower people of all ages to assume responsibility for creating sustainable futures" (Ravindranath, 2007:191-192). Second, Le Grand (1991:42) posits that one cannot have an unlimited approach to respond to the needs of others. Equity is achieved when certain minimum standards for treatment are adhered to and when their (people's) sacrifices are taken into account to secure equitable treatment. For example, one is treated equitably if one's needs are attended to minimally - that is, if one does not make unrealistic demands in terms of one's needs, and if one has made an attempt to address one's needs. Third, the literature on development abounds, where the following view on development was seen as notable: development is economic development (ED), and the latter is equated with economic growth. Development is considered as 'good change' in the realm of ecology, economics and all spheres of societal, political and cultural life (Chambers, 2004 in Ngowi, 2009:260).

Results

In this section, the main findings are presented firstly from an analysis of the three films in succession as introduced. For all learners' comments to remain anonymous, the researcher used appropriate abbreviations.

Analysis of Sustainable Development (Film 1 -An Inconvenient Truth)

The issue of sustainability in education as an instance of social justice ought to be widely advocated for: Fien (2002:143) holds that sustainable development can contribute to harnessing more informed understandings of 'principles of the Earth Charter' , namely environmental protection, human rights, equitable human development, and peace in relation to the achievement of justice through education; Stables and Scott (2002:53) claim that SD is a notion of (environmental) education that brings human reflexivity into just dialogue with the environment; and Suave (2005:30) posits that SD makes explicit concerns for human development, the maintenance of life and the cultivation of social equity.

Despite the various actions taken at international level to address SD, much is still to be done at regional and local levels (Filho, 2011). According to Filho (2011:14), following the publications of 'our common future', Agenda 21 and the worlds commitment towards sustainability reiterated in the 'Johannesburg Declaration' the need for disseminating approaches, methods, projects and initiatives aimed at fostering the cause of SD is as pressing as ever before. It is within this article that I address this concern through teaching for SD, an aspect of social justice, with the aid of the film An Inconvenient Truth.

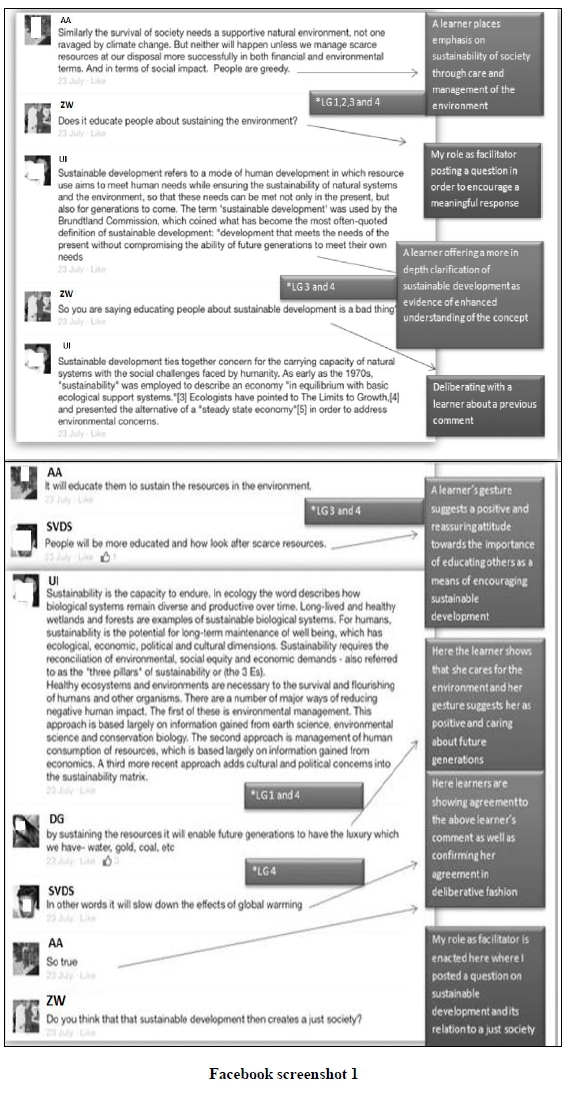

At the level of interpretation, I offer the following narrative. Whereas some learners' responses were (learners UI and RL) somewhat confusing in the beginning, and not directly related to the link between SD and social justice, other learners' responses were informed and to the point. For example, learner AA links the 'survival of society' to the adequate management of scarce resources and the decrease of climate change. The thoughtful argument learner AA produced is that the protection of the environment will reduce climate change, which in turn will enhance SD.

Moreover, the learners made a concerted effort to find out what SD means. Learner UI clearly drew on the Brundtland Commission's (1987) definition of SD (refer to Facebook screenshot 1), which intimates that people in society are required to cater for the needs of the present generations, without compromising what future generations can experience.

Likewise, as confirmed by learner SVDS (refer to Facebook screenshot 1), the film An Inconvenient Truth teaches learners to care for the environment and the material resources that possibly could contribute to a better place of living. As learner DG (refer to Facebook screenshot 1) confirmed, future generations have a right to access material resources, and people ought not exploit resources to such an extent that future generations are left with few resources to sustain themselves and the environment, which stands as another example of the Brundtland Commission's (1987) view. In other words, an unsustainable environment would have devastating consequences, such as global warming.

Remarkably, learner ST (refer to Facebook screenshot 2) has come up with practical steps, which she derived from her analysis of the film, to prevent unsustainable development. Here, she and other learners suggested that those who act irresponsibility ought to be subjected to prosecution by the law, thus making the call for SD highly political.

In sum, the learners were conscientised about the negative and harmful effects of unsustainable development. The learners not only acquired knowledge of the concept of SD, but also came up with strategies as to how unsustainable development ought to be combatted. This is a clear indication that the film assisted learners in their learning. They also developed the skills to come up with solutions for the way in which unsustainable development might be addressed and remedied. Their learning was demonstrably enhanced and their enthusiasm for the subject Economics increased, as they had acquired some of the learning goals associated with learning Economics. In other words, their sense of social justice was enhanced. As confirmed by another learner (ST) during an interview: "I have become more aware through educational skills and organisations within society, and I also think that all citizens have an important role to play in improving the standard of living in society. I have learnt that education is the key to improving the standard of living of people, because without it, they won't have access to basic needs and also, they won't be able to provide for their future. In my opinion I think that education [for social justice] is the wealth of a successful nation."

Analysis of Equity (Film 2: Into the Wild)

Julian Le Grand's (2007) analysis of equity claims that it involves performing minimum standards of treatment for those people who are in need of support; providing equality of "access in terms of the costs or sacrifices that people have had to make to get medical care"; and the attainment of full equality in terms of equal treatment for equal need (Le Grand, 1991:42). Equity is achieved when certain minimum standards for treatment are adhered to and when their (people's) sacrifices are taken into account to secure equitable treatment.

Analysing the learners' views on the film Into the Wild, the researcher found that their critical awareness of equity had been linked to an understanding of equality as a form of sameness. It is evident from the screenshots analysed that there is a great deal of inequity that exists in society and that, as individuals, we ought to educate others on the disparity in wealth that exists in society, which classes people according to their wealth. What should also be deduced from the screenshots is that the learners placed emphasis on the moral obligation of society to help others struggling to improve their living conditions. As individuals, we are confronted with the choice as to whether to make a meaningful contribution to the development of society, or whether we allow individual, immoral greed to persuade us to ignore a society comprised of poor people failing to make ends meet.

After viewing the film Into the Wild, the learners demonstrated acute awareness of this level of inequity that exists, where we have a minority of rich individuals with countless resources at their disposal, enjoying life and taking advantage of their wealth, and a vast majority of society struggling to cope within an endless cycle of poverty, and with minimal to no resources at their disposal. What also ought to be noted is that the learners showed a greater sense of responsibility towards the poor, and of the fact that, as individuals, we ought to be grateful for what we have in life, as opposed to allowing greed and corruption to entice us continuously to gain in profits and to advance the marginalisation of others.

What the learners also mentioned is that equity, as an element of social justice, means that there is no form of discrimination or prejudice in society, and that people are respected and recognised, irrespective of their race, religion, culture or class. What I inferred was that not every learner agreed with the possibility of social justice. One learner in particular (learner CP in Facebook screenshot 3), voiced his opinion that its attainment was unlikely due to the discrepancy in wealth that still exists in a largely unequal democratic society today. This is a result of a minimal if any change in efforts, more than 20 years after the advent of democracy in South Africa, to try to ensure the equitable distribution and use of resources by all citizens.

I deduced that the learners engaged in deliberative encounters. In the Facebook screenshots one can clearly see that learners worked together and engaged deliberatively, posing questions and justifying points of view. The learners were mutually engaging, and not interrupted or hindered by other learners during their engagement. They articulated themselves confidently as a result of having written down their points of view on inequitable lifestyles, on the basis of their understandings of the concept. They could equally make a point about the societal inequity that prevails. As remarked by learner SVDS (refer to Facebook screenshot 2), the learners understood "[that] equality [in reference to equity] teaches one to share resources equally amongst the rich and poor for example"; and "[that equity teaches us to] treat all people the same..." (refer to Facebook screenshot 4). Hence, it can be inferred that "the sharing or resources" and "treating people the same" can be considered as the main defences learners offered to justify their understandings of equity albeit a truncated view in light of Le Grand's (2007) position on equity. For the very least, they could be said to have had an awareness that equity relates to the 'fair' treatment of people on the basis of equality.

Moreover, what ought to be noted is that the learners were critically aware of the need for reconstruction, growth and development, which are integral to addressing the issue of inequity within a society. The learners were also critical in analysing the practices, values and attitudes pertaining to the Economics curriculum. Likewise, the learners emphasised the need to be treated equitably. In the Facebook screenshot, learners can be seen to emphasise the importance of equity in overcoming issues of discrimination in society. What should also be noted in the screenshots is that the learners emphasised the importance of actions, processes and structures in society that advance equitable redress, that is, people intent on seeing that societal equity will work towards bringing about such change (learner AA in Facebook screenshot 2). The film Into the Wild played an integral part in shaping their views on what is required by them as individuals to aid in the equitable change that society so desperately needs to undergo.

The point is that the learners' awareness of the need for societal equity as a desired goal is evident. Of course, their understanding might not have been sufficiently critical, considering their emphases on sameness and not necessarily on difference (as Le Grand holds), but it (their understanding) is sufficiently justifiable in relation to redress and societal transformation.

Furthermore, it ought to be noted in reference to learner KAP and learner JM (in Facebook screenshot 3) that the learners developed a critical awareness of societal inequities that can only be addressed, they argue, through fairness, and the equitable distribution of material resources. In critically analysing the inequities of the past and present, specifically relating to issues such as wealth and poverty, the learners raised the importance of getting to understand the policies, practices and actions that can contribute towards eradicating societal inequities, which serves as an indication that they had familiarised themselves with the importance of the learning goal of economic pursuits.

Likewise, and quite importantly, learners such as learner JL and learner AA (in Facebook screenshot 3) expressed a serious concern for equity. In JL's words, "[in] a just society [...] people learn to share all the resources equally and it doesn't matter whether you are rich or poor [...]", that is, the student expresses the significance of working collaboratively towards an equitable society in which resources are shared equally and appreciated by all citizens, which is an important dimension of education for social justice.

It can be observed from this that the learning goals of the Grade 11 Economics curriculum articulate the importance of equity on the basis that people in society need to be encouraged to share resources equally. The learners' optimism in the pursuit of an equitable society through human agency, in which the exclusion and marginalisation of the underprivileged could be transformed, is clearly inferred in the remark of learner RVDR (in Facebook screenshot 4).

The learners' analyses of Into the Wild all point towards the importance of cooperatively working together to eradicate societal inequities, as is evident in the comments of learner ST (in Facebook screenshot 4). In other words, an education for social justice through equity is only possible if human beings realise that the potential of cooperation and equal participation in developing a just and inclusive democracy is an important pedagogical imperative, particularly if the learners were to play some role in contributing to classroom change, with the aim that such change might spill over into a desire to bring about change in society.

Similarly, the learners (with reference to learner CP in Facebook screenshot 3) also acknowledged the role the researcher played in facilitating discussion, without influencing the main debates, showed that the researcher treated them as equals - that is, that I recognised their equal ability to speak their minds and to arrive at some articulation about societal (in)equity.

Hence, the learners' analyses of Into the Wild, their awareness and the skills they used in coming to terms with societal inequities suggest that they engaged in a education for social justice for two reasons: first, they developed an understanding of the negative effects of societal inequities; and second, they showed a need to want to contribute towards the eradication of such inequities - a key aspect of the learning goals of the Economics curriculum. The learners developed an awareness of "[...] contemporary economic, political and social issues around the world [... ] I can also influence people to start groups to fight for social justice and to lead to peace and combat global warming and so forth" (learner AD during an interview). Another learner put forward that "the aims and designated goals of the new Economics curriculum was [sic] to present the information in a manner that would allow students to form their own analytical and critical opinions about these issues . now when I hear of these issues I am able to contribute relevant information whether in the classroom or outside" (learner DG during an interview) - a verification that some of the learning goals of Economics have been acquired in relation to an education for social justice. In other words, learning about an education for social justice through equity was an important milestone for the learners, as confirmed by learner RVDR in an interview: "in my opinion learning about social justice in education is important because it makes everyone aware. It also educates others about equality; respect for one another in a socially just environment." In essence, the researcher could infer from the Facebook screenshots on equity that the learners envisaged the cultivation of a education for social justice on the basis of stronger deliberation, criticality and inclusivity.

Analysis of Economic Development (Film 3: The Gods Must Be Crazy)

Seers (1972 in Ngowi, 2009:260) posits that economic development means creating conditions to realise human potential, reduce poverty and social inequalities, and create employment opportunities. Economic development has to do with the economic wellbeing, output, infrastructure, health, education, political and cultural aspects of people's lives and "good governance" (Kabuya, 2011:2).

A study conducted by the World Bank found that economic growth rates in a sample of 60 countries during the period of 1965-1987 were particularly high, where there was a combination of a high level of education and macroeconomic stability (Tilak, 1989 in Ozturk, 2001:6). Again, in this article, I show that through teaching for economic development, with the aid of the film The Gods Must Be Crazy, engendered socially just relations in the classroom most apposite the field of economics and education.

Analysing the learners' views on the film The Gods Must Be Crazy, I found that learner awareness of economic development had been enhanced. They learnt and inferred perspectives on economic desert, an understanding of which is a key feature of social justice. The learners became cognisant of the fact that economic development contributes to improvement of people's standard of living and their productivity and efficiency, as stated by learner ST (in Facebook screenshot 5): "it helps society to maintain things [such as standard of living] and improve on development within a country. It makes the country stronger [such as to produce more and equitably distributing its resources]." Economic development would thus enhance the economic fortitude for all people in society, which would constitute achieving full social justice.

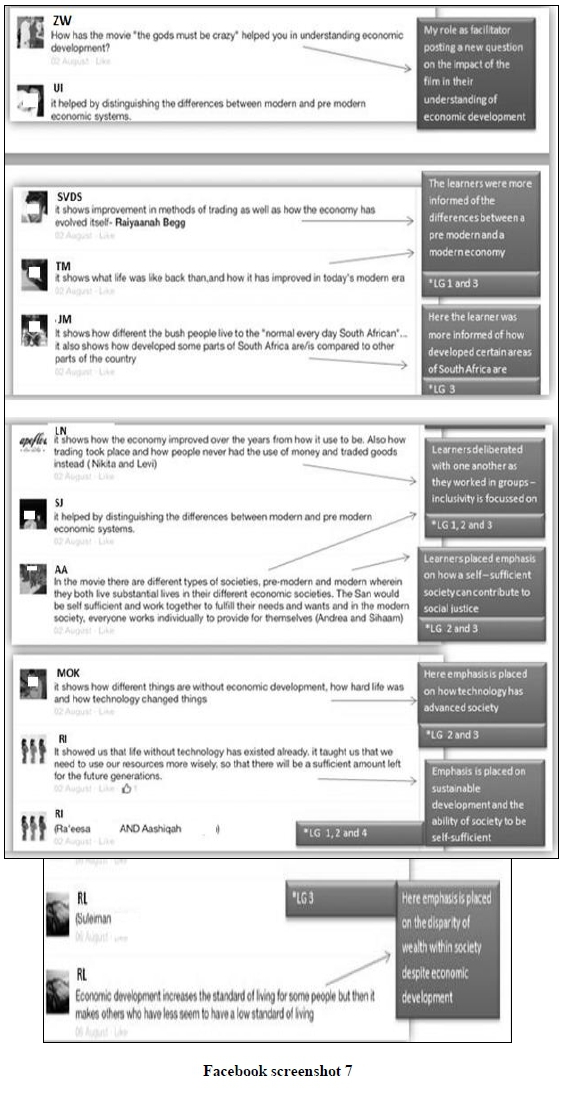

The learners' critical awareness and understanding of economic development also increased in the sense that they could distinguish between pre-modern and modern societies on the basis that the former relied on people working together, whereas excessive individualism seem to be dominant in the latter - often resulting in an inequitable allocation of economic resources; the ' haves' want more profits through greed, and those who are marginalised, the 'have nots', seem to be excluded from competition with dominant wealth. In this regard, learner AA (in Facebook screenshot 5) remarked: "in the movie there are different types of societies, pre-modern and modern wherein they [people in different societies] both live substantial lives in the different economic societies. The San [considered as pre-modern people] would be selfsufficient working together to fulfil their needs and in the modern society everyone works individually to provide for themselves."

In addition to advocating that economic development improves living standards, the learners also emphasised the importance of living modestly in terms of using resources, and addressing disparities and inequities in society.

Learner CP (in Facebook screenshot 6) had the view that resources ought to be used to improve people's lives, whereas learner RL (in Facebook screenshot 6) advocated for the sharing of resources on an equitable basis, aimed especially at improving the lives of the less advantaged (a Rawlsian perspective). This gives clear vindication for the task, showing that the learners had acquired some knowledge of economic development, and also had developed the skills to question and come up with suggestions on how contemporary challenges relating to resources could be attended to in terms of their equitable distribution amongst all people in society. What was most striking and profound during my analysis of the Facebook screenshots dealing with the issues of economic development was the learners' capacity to engage in deliberative encounters and to express their points of view autonomously, to the extent that they made, at times, informed suggestions. Learner JL (in Facebook screenshot 6) stated that resources ought to be used and shared 'more wisely' - that is, equitably, and quite importantly, they (the learners) expressed a serious concern for caring for resources.

Based on the aforementioned views of learners in relation to economic development, it appears evident that some of the learning goals of the Grade 11 Economics curriculum had been practised in relation to articulating the importance of desert through an awareness of some of the goals of economic development. The fact that the learners' understanding, skills, critical awareness and knowledge were enhanced in relation to processes, standards of living and the relevant distribution of resources is a manifestation of the fact that they have learnt to be responsive to an issue of social justice - that is, economic development. This claim is evinced by learner LN's comment in an interview as follows: "I have become more [aware] of the living standards once I have seen the conditions poor people are living in. In order for living standards of people to improve, poverty needs to decrease in order for more residents to receive employment. Also through improving the standard of quality education by developing new universities, training colleges and so forth would subsequently improve employment. This improvement would result in people earning a decent wage or salary, so that they would be able to provide for their basic needs."

The learners' views on The Gods Must Be Crazy, as confirmed by learner JM (refer to Facebook screenshot 7), were couched in a concise statement pointing out the differences between developed and under-developed economies, specifically in reference to local economic development (LED) in South Africa. Learner AA pointed out the significance of building an economy through collective action - that is, the 'pre-modern' San people 'working together to fulfill their needs' unlike the individualism that has come to dominate development in modern societies. Learner RLK (refer to Facebook screenshot 7) emphasised the important role technology plays in enhancing economic development, which is also confirmed by learner NA (refer to Facebook screenshot 7). Yet, this learner cautioned against an over-reliance on technology. Learner CP pointed out the importance of economic development in improving people's "standard[s] of living" - this poignantly links economic development (ED) to the critical dimension of improvement (refer to Facebook screenshot 6). In this regard, learner RL confirmed that ED, if it advantages some people in society only, can bring about inequality, thus resulting in a lowering of others' standard of living (refer to Facebook screenshot 7). To come back to the distinction made between economic development and LED on the basis of individual and collective action, it seemed as if learners emphasised the importance of social action in relation to economic development. And, African communities, like the San (Bushmen people), are intent on working cooperatively in a spirit of Ubuntu, viz. human interdependence through dignified action. So, the argument produced by learners in defence of LED is that people in communities ought to work together, instead of according to the individualism that seems to have come to dominate economic development in many contemporary societies. Of course, for scholars like Assié-Lumumba (2007), the notion that the common assumption that an African viewpoint on communal living is one that espouses collectivity and harmony, whilst the Eurocentric point of view of community emphasises a more individualistic orientation towards life, is perhaps a misconception. However, recognising African communalism ('working together') in pursuing economic development is significant in building communities, a viewpoint that seems to be confirmed by some of the learners when watching The Gods Must Be Crazy.

In sum, the learners offered insightful and at times informed views on how economic development, with its emphasis on financial reward, can justly improve the living conditions of all citizens in society. In the researcher's view, the learners not only showed orientation towards the eradication of societal inequities, especially the undesirable allocation of material resources and the obsession with greed and individualism, but also enacted a level of social justice in their deliberations with one another - that is, they shared ideas, improved on one another's points of view, and even suggested responsible ways in which the lives of all people in society can be improved. In this way, the learners were initiated into an education for social justice through the teaching and learning of economic development.

Conclusion

This article has shown through a discourse analysis of films, supported by asking probing questions on Facebook, that there is sufficient evidence to suggest that education for social justice can be taught and learnt in a school classroom in relation to the learning goals of Grade 11 Economics. Firstly, an analysis of An Inconvenient Truth in relation to Grade 11 Economics learning goals indicated that people's need for control over resources can become too excessive, often resulting in exclusion and inequitable treatment, especially of vulnerable people in developing societies. Consequently, education for social justice should not prejudice less powerful communities or put SD at risk by distributing resources inequitably amongst people. Secondly, an analysis of the film Into the Wild brought about discussion considering that people ought to be afforded equality of opportunity in order to make sure that societal inequities are addressed; and thirdly, an analysis of The Gods Must Be Crazy vindicates the importance of economic development in ensuring the equitable distribution of resources in order to be responsive to the requirements of economic desert. So, inasmuch as education for social justice has been attended to through teaching and learning, this concept was made even more profound when the pedagogical encounters between the learners and myself as the researcher took the form of deliberation, inclusion, equal expressiveness and an inclination towards social change, which are all aspects of an education for social justice.

References

Alba-Juez L 2009. Introducing discourse analysis. In L Alba-Juez (ed). Perspectives on discourse analysis: Theory and practice. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Assié-Lumumba NT 2007. Introduction: General issues and specific perspectives. In NT Assié-Lumumba (ed). Women and higher education in Africa: Reconceptualizing gender-based human capabilities and upgrading human rights to knowledge. Mansfield, OH: Book Masters. [ Links ]

Bell LA 1997. Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In M Adams, LA Bell & P Griffin (eds). Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brundtland Commission 1987. Our common future: The World Commission on Environment and Development. London, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cochran-Smith M 2004. Walking the road: Race, diversity, and social justice in teacher education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2001. Education White Paper 6. Special needs education: Building an inclusive education and training system. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Education. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Legislation/White%20paper/Education %20%20White%20Paper%206.pdf?ver=2008-03-05-104651-000. Accessed 20 April 2016. [ Links ]

Fien J 2002. Advancing sustainability in higher education: Issues and opportunities for research. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 3(3):243-253. doi: 10.1108/14676370210434705 [ Links ]

Filho WL 2011. Applied sustainable development: A way forward in promoting sustainable development in higher education institutions. In WL Filho (ed). Worlds trends in education for sustainable development. Manhattan, NY: Peter Lang Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Fraser N & Honneth A 2003. Redistribution or recognition?: A political-philosophical exchange. London, UK: Verso. [ Links ]

hooks B 2003. Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jørgensen M & Philips LJ 2002. Discourse analysis as theory and method. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Kabuya FI 2011. Development ideas in postindependence: Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 3(1):1-6. [ Links ]

Le Grand J 1991. Tales from the British National Health Service: Competition, cooperation or control? Health Affairs, 18:27-37. [ Links ]

Le Grand J (ed.) 2007. The other invisible hand: Delivering public services through choice and competition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Martin JR 2013. Education reconfigured: Culture, encounter, and change. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Michelli NM & Keiser DL (eds.) 2005. Teacher education for democracy and social justice. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Miller D 2003. Principles of social justice. London, UK: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

National Planning Commission, Republic of South Africa 2011. National Development Plan: Vision for 2030. Pretoria: National Planning Commission, Republic of South Africa. Available at http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/devplan_2.pdf. Accessed 20 April 2016. [ Links ]

Netshitenzhe J 2014. Inequality matters: South African trends and interventions. New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 53:8-13. [ Links ]

Ngowi HP 2009. Economic development and change in Tanzania since independence: The political leadership factor. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 3(4):259-267. [ Links ]

OECD 2008. Reviews of national policies for education: South Africa. Paris, France: OECD Publication. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Reviews%20of%20National %20Policies%20for%20Education%20-%20South%20Africa,%2016%20February%202009.pdf?ver=2011-01-18-113926-550. Accessed 18 April 2016. [ Links ]

OECD 2013. OECD economic surveys: South Africa 2013. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Available at http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/other/OECD%20Economic%20Surveys% 20South%20Africa%202013.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2016. [ Links ]

Ozturk I 2001. The role of education in economic development: a theoretical perspective. Journal of Rural Development and Administration, 33(1): 3947. [ Links ]

Ravindranath MJ 2007. Environmental education in teacher education in India: experiences and challenges in the United Nation's decade of education for sustainable development. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 33(2):191-206. doi: 10.1080/02607470701259481 [ Links ]

Rawls J 1971. A theory of justice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sleeter C 2013. Teaching for social justice in multicultural classrooms. Multicultural Education Review, 5(2):1-19. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2013.11102900 [ Links ]

Sleeter CE 2001. Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: Research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(2):94-106. doi: 10.1177/0022487101052002002 [ Links ]

Stables A & Scott W 2002. The quest of holism in education for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 8(1):53-60. doi: 10.1080/13504620120109655 [ Links ]

Suave L 2005. Current in environmental education: Mapping a complex and evolving pedagogical field. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 10(1):11-37. [ Links ]

Wodak R 2011. Critical discourse analysis. In K Hyland & B Paltridge (eds). The continuum companion to discourse analysis. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Zeichner KM 2005. A research agenda for teacher education. In M CoChran-Smith & KM Zeichner (eds). Studying teacher education: the report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers. [ Links ]