Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.35 no.2 Pretoria Mai. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n2a956

Social justice praxis in education: Towards sustainable management strategies

Idilette van DeventerI; Philip C van der WesthuizenII; Ferdinand J PotgieterIII

IResearch Unit Edu-HRight, Faculty of Education Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa Idilette.vanDeventer@nwu.ac.za

IIFaculty of Education Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

IIIResearch Unit Edu-HRight, Faculty of Education Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Social justice, defined as an impetus towards a socially just educational world, is based on the assumption that all people, irrespective of belief or societal position, are entitled to be treated according to the values of human rights, human dignity and equality. Diverging from the classical positivist approach in social science research that takes injustice as its impetus, the researchers departed from a socio-rationalist approach into exploring sustainable management strategies for effective social justice praxis. This approach has enabled the construction of a conceptual-theoretical framework and an iterative qualitative inquiry, which has as its central principal the sustainable management strategies for effective social justice praxis. Four key findings affirmed the belief that good praxis was to be found in Gemeinschaft relationships, in the influence exerted by government and education systems and structures, where government and principals were found to be co-responsible in ensuring that the best interest of the child was served. This responsibility included practices found in collaborative efforts, where communities became the guardians of their schools due to a disciplined school that followed constitutional values. Lastly, these practitioners aligned their management strategies with human rights values, as well as human dignity and equality, and their strategies found pride of place in extant ubuntu principles.

Keywords: determinants; education; human rights; management strategies; restorative; social justice praxis; sustainable development; transformative; ubuntu

Exigency for Effective Social Justice Praxis in a Socio-Rationalist World

Social justice - as an impetus towards a socially just world - is based on the assumption that all people, irrespective of belief or societal position, are entitled to be treated according to the values of human rights, human dignity and equality. It is evident from international and national media reports on the dire situation in many schools, however, that the movement towards social justice has remained unfulfilled. The outcomes attained in the South African education system, for instance, have been labelled as "the worst of all middle-income countries in cross-national assessments of educational achievement" (Spaull, 2013:3). A lack of education leadership and management invariably contributes to this situation (Bush, Kiggundu & Moorosi, 2011). Hargreaves and Fink (2006:1) concur, and state that "sustainable improvement depends on successful leadership. But making leadership sustainable is difficult too." South Africans in particular do not yet share to the fullest degree in such a sustainable leadership and effective social justice praxis (Spaull, 2013).

A Proposition-Based Inquiry

Diverging from the classical positivist approach in social science research, which is guided by an existing problem, that is, social injustices, this study set out from the proposition that not all school principals were contributing to injustices as they are to be found in the "growing evidence of exceedingly low levels of learning in many developing countries, including India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Thailand, Turkey, and South Africa" (Spaull & Taylor, 2015:137). Rather, the Appreciative Inquiry (AI) approach of Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros (2008) provided the opportunity to perform research from a constructive and affirming vantage point, so as to generate theory on sustainable organisational development. Those who follow the AI approach are conducting their research and theoretical propositions "in the service of their dynamically constituted vision of the good" (Cooperrider, Barrett & Srivastva, 2013:170). The AI approach offered concerns the theory development of organisations (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987, 1998), and is creating a positive revolution in the field of organisational development (Cooperrider et al., 2013). This article proposes that inquiry into effective, valuable praxis offers an alternative understanding of sustainable management interventions, rather than one informed by a problem-based approach, especially in an education system that is as complex and beleaguered as that which is to be found in South Africa. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: we commence by outlining the determinants of social justice praxis. This is followed by a conceptual-theoretical framework that forms the backdrop against which we performed the empirical investigation, where we then present a discussion of our findings and concluding remarks. Cooperrider and Srivastva (1987:129) postulate that AI researchers view science from a "socio-rationalist" perspective, and as social-rationalists, they are intensely involved with their own reality in an environment where trust-building, knowledge-sharing and increased social justice praxis become the norm (Calabrese, 2006).

Sustainable Management Strategies for Social Justice Praxis

Le Grange (2007:90) postulates that sustainable development in education is, inter alia, to be found in "people and people relationships" that observe the social justice principles of basic human needs, inter-generational equity, human rights and participation. However, Le Grange (2007:93) cautions that although sustainable development in South African education coincides with and is integral to school reform, the concept of sustainable development are embedded in "progress stories" about successful development and improvement. Le Grange (2007) argues that progress stories are not necessarily progressive or sustainable, nor do they necessarily lead to reforms as the outcomes-based 'saga' has shown. Such progress stories on sustainable development may even limit the impact of democracy and impede efforts towards social justice. We nevertheless argue that these stories of progress are important, as they affirm the belief that sustainable management of effective social justice praxis is indeed possible, as the participants' stories in this research showed in the discussion on sustainable management strategies for social justice praxis. These strategies also offer the space in which to rebuild a sustainable education system that realises the values of human dignity. In view of Le Grange's (2007) warning, it is important to first understand that the concept of social justice has two manifestations: justice as such, and social justice.

The essential being of justice manifests in society and is a reality that holds the inherent possibility to change individuals and institutions. Accordingly, justice as a concept underpins the concept of social justice. It provides a theoretical basis for the analysis and evaluation of social justice (not as onticity, but as modality of justice) in society and in institutions towards a transformed society. Social justice praxis (as a verb) includes acts of kindness towards others, with the aim to repair and transform the school and societal environments (Baillon & Brown, 2003). Social justice is a lived concept that encompasses acts of fairness, equality and justness towards others. Social justice acts in this sense are about how 'others' experience and understand complex concerns of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability or class. However, social justice is also relevant for those perceived to be privileged. Both the under-privileged and the privileged ought to share in the promise of fundamental human rights and the resultant praxis of justice as fair, equitable and equal.

Rawls (1999b, 1999c) proposes that social justice is related to a set of principles that provide a way of assigning rights and duties, both to individuals, and to organised communities (determinants) in basic institutions of society. These determinants of a well-ordered society are found in external individual cognition, recognisable in naming, conceptualising and labelling categories of social justice phenomena that are the social and historical creations of man. In Rawls' (1971) well-ordered society, there is an elucidation as to what constitutes just and unjust acts, whilst in his Theory of Justice, he proposes co-existence of state and individual public institutional spaces, such as schools (Rawls, 1999b). In these spaces, social justice is related to "a set of principles that provide a way of assigning rights and duties - both to individuals and organised communities" - through these fundamental social institutions (Van Deven-ter, 2013:22).

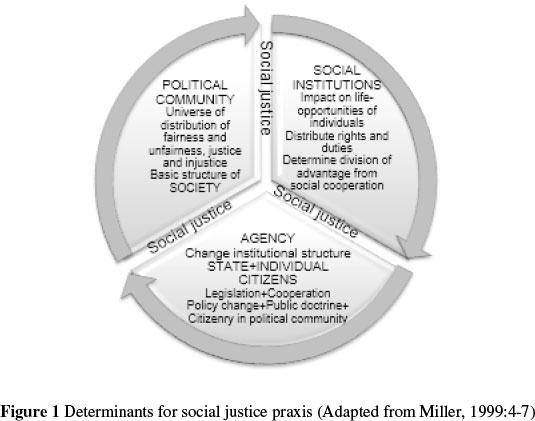

The meaning of a human society is to be found in the co-dependency and co-responsibility of its members; who all flourish - or not - in a particular society, where socially just communities, as well as the hopes and prospects of each individual and the greater society, are affected. A society ought to have an institutional structure formed by the state, education system, and individuals. Additionally, a society requires human agency to bring about deliberate and transformational reform in the name of fairness and justice for all its citizens (Miller, 1999) (Figure 1).

Determinants of Social Justice Praxis: Government, Institutions and Individuals

The realities of social justice and education management consist of government systems and school sub-systems that manifest interdependently (Potgieter, 1980). The scope of social justice praxis depends on a mutual understanding of who is responsible for determining the allocation or distribution of the good and bad, advantages and burdens, as well as rights and duties (Miller, 1999). Teachers who advocate for social justice praxis are as agents of change in schools, however this role ought to be shared between the state and social justice agents (Francis & Le Roux, 2011).

In such a collaborative engagement between the state and individuals, constitutional values and human rights provide the impetus for social justice praxis. Taking as its cue a divisive apartheid past, the preamble to the South African Constitution (Republic of South Africa, 1996a), as well as Section 1, both aim to heal the divisions of the past, and to establish a non-racist, non-sexist and democratic society based on the values of human dignity, equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms. These values should inform all educational management endeavours, from legislation, through to policy-making and praxis. As such, the Bill of Rights (s.7(2)) imparts to educationists (all role-players) to respect, protect, promote and fulfil constitutional provisions and the values it enshrines, to create a society that is the very opposite of the apartheid order. In addition, the legal and policy frameworks have to 'will' educators to attend to these values, so as to ensure the realisation thereof for all learners. The ideal of building a transformed schooling system is supported by a series of education white papers and policy frameworks (i.e. White Paper on Education and Training, notice 196, Department of Education, Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, 1995; Education White Paper 2: The Organisation, Governance and Funding of Schools, notice 130, Department of Education, 1996; as well as legislation (National Education Policy Act (NEPA) 27/1996 (Republic of South Africa, 1996b)); the South African Schools Act (SASA) 84/1996 (Republic of South Africa, 1996c); and the Employment of Educators Act 76/1998 (Republic of South Africa, 1998). Of particular importance is White Paper 3, which also mentions the ideal of a future where all South Africans will enjoy an improved and sustainable quality of life, participate in a growing economy, and share in a democratic culture.

However, education remains the centre of attention, due to the breakdown in the implementation of these policies at ground level. The right to human dignity is the most fundamental in any open and democratic society. This right imparts on the state the duty that the "dignity of man shall be inviolable" and should be protected by all state authority (Goolam, 2001:45). In addition, Goolam argues that inviolable and inalienable human rights form the basis of every society, system and institution of peace and justice in the world.

Scholars provide different stances to systemic and institutional determinants for the management of social justice praxis. Rawls (1999a) argues that distributive justice is a result of a cooperative venture of mutual benefit based on two principles, the principle of equal liberty for all, and the principle of difference, both of which should be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged persons in an equal society. Rawls' (1999d) theory of justice points towards fair and equal management, found in just institutions of government and education. Such a well-ordered educational society is governed by the relational conduct of those who are able to prioritise and make judgements on that which is right over that which is good. Leaders who make judgements as to what is 'right' base their decisions on consistent value-based conduct, which is beneficial and desirable for the individual, as well as for the school community more broadly.

Fraser (2009:72-73) extends Rawls' principles of equal liberty and difference to include claims for the recognition of cultural difference found in the "politics of recognition". She asserts that social justice understood as recognition is not assimilation into a dominant culture, rather, it is constituted by a world that embraces both redistribution of power, and resources, as well as recognition of cultural difference. Fraser (2009) argues that a politics of recognition in a difference-friendly world, is part of acknowledging the existence of difference, such as those based on ethnicity, racial diversity, or gender. This perspective locates social justice praxis in both the political-governmental and the local arena, as it describes those dimensions of justice that cut across all social strata.

The discourse about distribution and recognition should enhance the virtues of social consciousness, recognition of a common humanity, and a celebration of unity in diversity. Starratt (2009) proposes three virtuous acts to realise distribution and recognition as sustainable management in their praxis of responsibility, presence and authenticity. These acts ought to promote both the academic success of all learners, as well as be visible in the way in which they affect the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom. The virtue of responsibility and authenticity provide the subjective grounding and moral weight to the praxis of school leaders, who must act justly and fairly towards both those who are marginalised, as well as towards those groups privileged by social constructs (Starratt, 2009). Just and fair acts create a visible mindfulness of discriminatory, marginalising and unjust practices.

The virtue of authenticity affirms the school leader's critical presence in the lives of staff and learners, and establishes the required dialogue with the other. In being authentic, the school leader takes responsibility to express a positive or negative moral response to social injustice. In being present in the lives of teachers and learners, he or she mediates actions of authenticity and responsibility towards a fair and just educational landscape (Starratt, 2009).

School leaders who practice an ethics of care are focusing on personal and professional actions of respect. Such an ethics involves acts of integrity and cultural enrichment, namely the promotion of individuality, loyalty, human potential, dignity, and empowerment. An ethics of care brings to the fore a moral imperative of improving educational praxis and student outcomes for the marginalised and economically disadvantaged majority, who have not traditionally been served well in schools (Marshall & Oliva, 2010). Principals should understand, promote and enact social justice through a heightened and critical awareness of oppression, exclusion, and marginalisation that may have been experienced by their students (Freire, 2004). However, Brooks and Miles (2008) argue that awareness of social injustices is not sufficient in itself, because principals should, furthermore, act when they identify inequity; the authors point out that they are uniquely positioned to influence equitable educational practices, and that their proactive involvement is crucial.

Such a moral, dialogical integrity is found in the principles of ubuntu, underpinning educational professional development thought. According to Nafukho (2006) ubuntu is a concept described in, amongst others, the Southern African Nguni-language family (Ndebele, Swati/Swazi, IsiXhosa and IsiZulu) whilst omundu/muntu/ntu are Nguni words referring to humanity, or state of kindredness. Nafukho (2006) argues that the concept of ubuntu describes an African worldview, enshrined in the maxim 'umuntu ngumuntu nga-bantu' (a person is a person through other people).

Traditional African learning articulates a basic respect and compassion for others in society. Nafukho (2006) proclaims that ubuntu provides the rule of conduct (social justice) or social ethics in society. This model of interrelation promotes religiosity, spirituality, consensus and dialogue.

According to the United Nations (UN) (2006, 2013) governments should be compelled to put in place measures that will enhance equal liberty and recognise diversity, such that they are able to represent and serve the best interest of their populations. The broader international context, the pre-amble to the UN Charter expresses commitment to justice in affirming human worth in the form of dignity, fundamental and equal human rights (UN, 2006). Mahlomaholo (2011) asserts that the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) on sustainable development resonate in almost all legislative and policy imperatives and emphasise equity, social justice, freedom, peace and hope. Educational transformation, however, is dependent on a socially just educational environment that place equal value on the social justice principles of distribution and recognition (Garrett, 2010).

Education delivery is determined by management strategies executed by a person or body-in-authority (Van der Westhuizen, 1991), and is regarded by Manning (2001) to manifest in managed conversations. Social justice leaders in schools are constantly in conversation with themselves in self-reflective praxis and in dialogue with others. Intrinsically, they become agents of change in the broader educational system, and in schools. As agents of change they embrace and enhance diversity in being critically conscious of difference and sameness in a multi-, inter- and transcultural world (Van Vuuren, Van der Westhuizen & Van der Walt, 2012). Guilherme and Dietz (2015) argue that these layered concepts of diversity, consciousness, and multi, inter and transcultural difference are often used ubiquitously and indis-criminantly. The idea of diversity in education should be explored from both a monocultural and essentialising multicultural perspective as individual and collective phenomena in schools. These school leaders are bridging leaders, who overtly or covertly address inequity (Merchant & Shoho, 2010) in and through their actioned management strategies. These management strategies provide strategic direction and hope to school leaders, where matters of diversity - particularity in the school system - are encountered on a daily basis Dantley & Tillman, 2010).

Traditionally SWOT-analyses focused on the monitoring and evaluation of an organisation's strengths (S) and weaknesses (W), opportunities (O) and threats (T). However, Stavros and Hinrichs (2009) advance the SOAR strategic planning framework, i.e. building on Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations and (measurable) Results. This framework focuses on strengths, and seeks to understand the whole system by including the voices of the relevant stakeholders on those aspects at which an organisation excels, which skills could be further developed, and that which "is compelling to those who have a 'stake' in the organization's [sic] success" (Stavros & Hinrichs, 2009:20). For Mintz-berg (1989:69), strategy making is about an inner awareness found in the "mysteries of intuition", whilst Freire (2007:69) defines it as "revolutionary leadership" and "co-intentional education".

The obligation to ensure that sustainable management strategies are put in place is not only a moral one; it also implies an ongoing social agenda. In this regard, the responsibility towards social justice when devising these strategies is not restricted to the level of policy-making. It should, rather, be extended to the level of both government (at macro level) and schools (at micro level). Strategy making steers essential actions in a consistent, purposeful and coordinated manner, through continuous improvement against determinates of good practice, as described above.

Empirical Investigation

Since this research employed a socio-constructive framework to understand social justice praxis, it calls attention to individual sense-making, and to the construction of principals' social and psychological worlds. These worlds are constructed and co-constructed through rational social processes of communication and interaction.

A Qualitative Social-Constructivist Research Design The empirical study entailed a qualitative social-constructivist research design (Merriam, 2009) to understand and interpret, albeit subjectively, the meaning that participant-principals attached to their successful management strategies, in order to enhance sustainable social justice praxis. Social-constructivists generally view reality as relative, constantly changing, and informed by linguistic convention.

Sampling and Research Instrument A disproportional stratified purposive sampling procedure was followed, based on principles of fairness, and theoretical constructs (Mouton, 2001). District Officials in two South African provincial departments of education performed the purposive selection task in accordance with pre-determined criteria. These officials used their own discretion in determining whether the selected principals met the predetermined criteria. The criteria these principals were obliged to meet were, firstly, that they understood the concepts of justice and social justice praxis, secondly, that they adhered to and implemented legal, systemic and institutional determinants, and thirdly, that they acknowledged the need for fair distribution and educational transformation. The assumption was that general best social justice praxis could be found in the management work that the chosen school principals maintained. No biographical data of the officials was solicited. Being independently and externally chosen by their superiors affirmed that, as transformative leaders, they were not only oriented towards social justice, but that they indeed practiced it. However, they did not proportionally reflect the population.

Two of the four district officials in the NorthWest Province selected 14 participant-principals, who took part in individual interviews. Accidental sampling (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010) resulted in two focus-group interviews in one school district in the Western Cape, with 11 participants. Interviews were conducted in Afrikaans (presented below in translated version) and in English (verbatim).

An interview schedule served as a personal impression memo to contextualise specific schools, attitudes, and the rapport between the researchers and the participant-principals. The questions focused on the participants' role to ensure effective social justice praxis and their understanding of constitutional values and management strategies to realise these values. They were asked to share positive and negative experiences, along with their staff's preparedness for social justice in education. Lastly, they were asked to identify those who were responsible for effective social justice praxis in their schools.

The findings of this study are generalisable to the sample only. As with transferability, general-isability of this research would not lie with the researchers, but with those principals, policymakers and scholars who might use these management strategies in the future (Marshall & Rossman,2011).

Trustworthiness, Ethical Considerations and Transferability

Rigid criteria validated the trustworthiness and soundness of the research (Marshall & Rossman, 2011). Trustworthiness was established where the selection criteria (discussed above) was credible. The interaction with the participants brought about raised levels of awareness and reflexivity on the part of both the researchers and the researched, which formed the catalyst for action that would follow in the proposed management strategies (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010). Qualitative trustworthiness was evident in the ensuing relationships, which were ethical, respectful and which continued long after the interviews with the participants (Guba & Lincoln, 2005).

The following ethical aspects were accounted for (Mouton, 2001): protection from harm, informed consent, right to privacy, honesty with professional colleagues, internal review boards, and adherence to the professional code of ethics of the university under whose auspices this research was done. The rights and expectations of participants were respected and anonymity and confidentiality guaranteed. The purpose of the research was communicated in a clear and honest manner and, as far as possible, no intrusion in the professional lives of the participants was allowed.

Data Analysis and Processing The decision to use a qualitative constructivist research design was based on the premise that the data thus collected, analysed and interpreted would yield a deeper understanding of the qualitative data (Marshall & Rossman, 2011) in accordance with the research premise that social justice praxis was to be found in schools. The researchers recognised that constant change in social justice as a phenomenon, and of qualitative data analysis, was inevitable. The findings of the qualitative data analysis were generated from the 12 semi-structured, individual, and two focus-group interviews. The process involved organising, perusal, classification and synthesis. From these actions, the data processing followed three phases and 18 steps. Phase I started with data recording, transcription and decon-struction of the first Atlas.tiTM transcripts. Phase II included the final construction of the Hermeneutic Unit: Social Justice in Atlas.tiTM from which an Atlas.tiTM code list emerged. Phase III commenced with the construction of an Excel-file, an Atlas.tiTM Frequency Table and network heuristics (Creswell, 2012; Merriam, 2009) that resulted in seven management strategies, of which four are reported in this article (Figure 2): optimising principal's virtues as Gemeinschaft relationships, influencing the education system and its structures, fostering a disciplined school environment based on constitutional values and a sustained social justice praxis, based on compassion, love and care.

Findings and Discussion

Principals' Management Strategy as Gemeinschaft Relationships

Principals optimised the virtues of responsibility, authenticity and presence (Starratt, 2009) as Ge-meinschaft (community) relationships towards effective social justice praxis. Whereas these principals upheld the constitutional values of human rights, human dignity, equality and social justice, which included non-discrimination on the basis of race, it should be noted that the endemic racial divide is very much alive and well in education. Contextualisation of race in this discussion was, therefore necessary in order to clarify participant-principals' stance against racialism and other injustices. Fairness formed the bedrock of their personal agency and responsibility for sustainable social justice. They were actively engaged in issues of "a life of justice, truth and respect based on shared values" (Calabrese, 2006:173), and these principals were astute activists and sensitive towards a "culturally diverse learner and teacher corps." Social justice praxis was the praxis of "love, an attitude of the heart ("hartsaak"), nondiscrimination and acceptance of the wonder of diversity of humankind which enabled ownership." The virtue of responsibility informed the socially just activities of these principals towards those who are marginalised, but also towards those privileged in society, affirming Starratt's (2009) notion that responsibility returns to authenticity for its subjective grounding and moral weight in expressing a positive or negative moral response to social injustices.

One principal believed that it was important for teachers or school staff in "monoracial and monolingual schools to attend courses to prepare them to teach" in a diverse reality, stating "we need teachers, schools, school principals and management teams who want to do the right thing for our country." The principle of redistributive justice is regarded as normative in a cooperative venture of mutual benefit (Rawls, 1999a) and mutual respect. Another, when asked what her understanding of social justice praxis was, said "basically it's [...] our daily bread, [...] we live with it, we live it, every time everywhere you are, for as long as you're living with people, you must encounter social justice." Being a Hindu, another said "[b]efore even reading the Constitution and books ... we were born with these things, you know when you are brought up as a child, these things are instilled in us: you know that [you] need to respect [others]."i The social justice praxis reported by these principals illuminate the manner in which practice and values are connected, in the sense that the "dignity of man shall be inviolable" (Department of Education, Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, 1995; Goolam, 2001:45).

Influence Education Systems and Structures

The second management strategy that ran like a fils rouge throughout the interviews, was that government and union officials ought to be persuaded to influence political matters that would serve the best interest of the child. This became evident in relation to disabilities and special education needs, where principals referred to "learners who were not able to read, subtract ... because primary schools followed a 'pass-one-pass-all' policy", which led to a bottleneck situation in secondary schools. This situation affirms the existence of a mismatch between actual learner achievement and government policies of the state as distributing agency (Miller, 1999).

Language as a barrier to access, but also as mother tongue and surrounding policy came to the fore where a principal [Afrikaans, white, male] said "I had to manage two schools on one premises, an Afrikaans and Setswana school" with a "racial division of labour between teachers and learners." He changed this situation by implementing a new integrated timetable, declaring that "they would manage the school as a single unit, no you and us, but a unitary system for all of us." He believed that "the best teacher with the highest qualification would teach all the Grade 12s in a specific subject, [i.e.] the best maths teacher whose first language was Afrikaans would teach the Afrikaans group, and then immediately thereafter he would teach the English group." Another principal [Afrikaans, Coloured/person of colour, male] managed "thirteen languages of mother tongue speakers; where multimillionaires' children were sitting next to children from the squatter camps, where powerful religious groups could be found and each form of diversity existed." Principals focused on social justice may find that the management of diversity and social justice remains a challenge. Yet, in being responsible, authentic and present in the lives of learners (Starratt, 2009) they contribute to a conscious acceptance of diversity.

These principals did not regard the state as the sole agent to institute and implement government policies, nor was the state seen as the sole distributing agent of good (and bad) practices in schools. As social justice practitioners they in collaborating with the state, took responsibility, and understood that all social activities and concurrent praxis (Miller, 1999) were theirs as well.

Inculcate a Disciplined School Environment based on Constitutional Values

Basic education is primarily about learners and their cognitive and, importantly, social development, in a sustained environment. Developing people is a fundamental task of school leaders (Leithwood & Jantzi, 2009) and is essentially linked to citizenship. Management strategies do, we suggest, inculcate a disciplined school environment for learners to embrace human diversity and dignity, democracy and ubuntu principles (Nafukho, 2006). Data analysis confirmed that the broader institutional framework of education ought to be influenced by those in power so as to optimise effective social justice praxis.

School safety and the story told by one principal [person of colour] was about a school that experienced a number of burglaries, due to its location amongst squatter camps. The principal noted that "schools were virtually plundered", but he convinced the school community that a school is "this ray of light almost like a lighthouse, where people would gather, and not a place where half of the school was carried away" [sic]. He believed that "the school did not need a fence, the community should be that fence, and the fence should not be there to keep children inside, the learners should be in the school because they want [...] to be there." This approach ultimately spread through the community in question, where burglaries subsequently became isolated incidents. This instance confirms Nieuwenhuis's (2010) understanding of social justice from a holistic perspective, where it would be seen to continuously challenge past injustices and practices.

Sustainable Management Strategies for Social Justice Praxis because of Compassion, Love and Care

The fourth strategy was that school principals in a diverse school environment were obliged to act-ualise sustained management strategies for social justice praxis with compassion, love and care. One of the major themes was diversity, which became evident in relation to racial and cultural differences with regard to disciplinary matters. Traditional methods of classroom discipline no longer worked, because "black learners, although 'born free' [sic], learnt how to use numbers in their favour, as opposed to white learners, who would not have the support of peers if they challenged unfair authoritarian behaviour."

Fairness and discipline was a sine qua non for black learners when it came to disciplinary matters. Social justice should be a process of conscience building, of becoming acutely aware of a heightened and critical awareness of oppression, exclusion, and marginalisation (Freire, 2004). This consciousness of the potential consequences of cultural difference becomes evident in teachers who "recognised and respected black learners' propensity to sing, dance and move." One believed that "white teachers succumbed to white political guilt, and were more lenient towards black learners than their black colleagues would be." These examples of push-and-pull forces lie at the heart of what Kurland (1997) refers to as relationships that brought harmony or conflict, abundance or waste, human development or degradation, a culture of life or a culture of death, equality or fairness.

Colour blindness was found in the petit récits by a principal of colour: a Korean missionary used the parable of all people being brothers and sisters, who needed to work together and take care of one another. When he was about to leave, a little white girl said "my sister is not feeling well, can you please pray for her?" He said, "yes sure, come let's pray for her. Where's your sister? She's in the class." She went to fetch her 'sister' and to the missionary's surprise, he saw that she was black and not white. The principal affirmed later that the white girl was influenced to perceive her friend as her sister, since this little girl didn't appear to notice colour in the girl, who she had adopted as if her own sister.

It is this manner of indifference to race that the South African Constitution asks for in the shared aspirations of a nation, in terms of the values and the moral and ethical direction the nation identified for its future. Principals agreed that values and ethical conduct was of paramount importance to creating a sustainable, socially just school environment, a kind of "über form of social consensus" (Begley & Stefkovich, 2007:400).

These principals displayed what Starratt (2012) calls mature qualities of autonomy, connectedness and transcendence. However, the problem of conflicting home and school values was noted by study participants, where one expressed, "we have to instill [...] the proper values, which is difficult, because some of our values differ from the values they bring from home. A simple example: a boy may say to you, 'why may I not smoke, because my parents give me money for cigarettes?' There's a conflict of [. ] values [at play in such a situation], and to bring about a mind change is quite difficult -you have to sit with that child and you have to show him the pros and the cons in connection with the issue."ii Another said the learners "can't wait to hear what you're saying and it's because of discipline, tradition, and values and morals [they experience in a school environment], that they allow you to teach them!''iii In addition, principals agreed that a vision of educational reform and social transformation was the result of a person-to-person (Le Grange, 2007) cooperation, where ownership was affirmed by a white female principal of a primarily black school. She told the parents "you know what, this is not my school, it is your school, it is your school, I'm working for you! You are my boss, you must come and tell me if I do something wrong" [sic]. Her voice and demeanour conveyed a sense of her conviction that she and the school form part of a community of parents, acknowledging a sense of collective 'ownership'. Principals in this study created a sustainable environment in which a change of heart occurred, where teaching was seen to involve "walking on holy ground. ." This leads to a closing consideration: we are walking, by the grace of the child who allows us to, on sacred ground, when it comes to their physical, emotional and spiritual wellbeing.

These four key findings affirmed the a priori supposition that management strategies for effective social justice praxis were to be found in schools.

Conclusion

Although primarily a South African-based inquiry, the recommendations have wider implications for sustainable social justice leadership. A fils rouge throughout the research is that defining social justice amounts to the inclusion of those individual acts towards the 'other' that require from each individual that which is necessary for the common good to prevail in their schools. It is proposed that leaders in education, on individual and universal levels, ought to incorporate social justice praxis in their active engagement with learners. Social justice praxis ought to become a personal conviction, a conviction that embraces government policies into praxis, albeit in a critical way. The progress stories told confirm and acknowledge the belief that sustainable management of effective social justice praxis is, indeed, possible. Moreover, their stories offer management strategies with which to rebuild a sustainable and coherent education system. This investigation and the interactions with the participant-principals left the researchers with a deeper insight into their management strategies, and how they shared their beliefs on social justice praxis without discrimination, a praxis that was fair towards the disadvantaged as well as the privileged. These principals' management practices were based on the constitutional values of democracy, human dignity and equality, and they advanced human rights fairly to establish a non-racist and non-sexist school environment. The participant-principals' management strategies celebrated a shared commitment to, and a responsibility towards increasingly sustainable efforts to further social change, as well as celebrating diversity and cultural enrichment, both in schools and in society more broadly. By so doing, their social justice praxis substantiated the speculation that inquiry into effective, valuable praxis offers an alternative understanding of sustainable management interventions.

Acknowledgement

Prof. Hannes van der Walt for his invaluable support and guidance during the article writing-learning process.

Notes

i. Verbatim quotation was edited for the publication.

ii. Verbatim quotation was edited for the publication.

iii. Verbatim quotation was edited for the publication.

References

Baillon S & Brown E 2003. Social justice in education: a framework. In M Griffiths (ed). Action for social justice in education: Fairly different. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Begley PT & Stefkovich J 2007. Integrating values and ethics into post secondary teaching for leadership development: Principles, concepts, and strategies. Journal of Educational Administration, 45(4):398- 412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09578230710762427 [ Links ]

Brooks JS & Miles MT 2008. From scientific management to social justice...and back again? Pedagogical shifts in the study and practice of educational leadership. In AH Normore (ed). Leadership for social justice: Promoting equity and excellence through inquiry and reflective practice. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Bush T, Kiggundu E & Moorosi P 2011. Preparing new principals in South Africa: the ACE School Leadership Programme. South African Journal of Education, 31(1):31-43. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/scielophp?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-01002011000100003. Accessed 21 February 2015. [ Links ]

Calabrese RL 2006. Building social capital through the use of an appreciative inquiry theoretical perspective in a school and university partnership. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(3):173-182. [ Links ]

Cooperrider D, Barrett F & Srivastva S 2013. Social construction and appreciative inquiry: a journey in organizational theory. In DM Hosking, HP Dachler & KJ Gergen (eds). Management and organization: Relational alternatives to individualism. Ohio, USA: Taos Institute Publications. Available at http://www.taosinstitute.net/Websites/taos/images/PublicationsWorldShare/ManagementandOrganization.pdf. Accessed 26 November 2014. [ Links ]

Cooperrider DL & Srivastva S 1987. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In RW Woodman & WA Pasmore (eds). Research in organizational change and development (Vol. 1). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Cooperrider DL & Srivastva S 1998. An invitation to organizational wisdom and executive courage. In S Srivastva & DL Cooperrider (eds). Organizational wisdom and executive courage. San Francisco, CA: The New Lexington Press. [ Links ]

Cooperrider DL, Whitney D & Stavros JM 2008. Appreciative inquiry handbook for leaders of change (2nd ed). Brunswick, OH: Crown Custom Publishing. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2012. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed). Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dantley ME & Tillman LC 2010. Social justice and moral transformative leadership. In C Marshall & M Oliva (eds). Leadership for social justice: making revolutions in education (2nd ed). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

Department of Education, Parliament of the Republic of South Africa 1995. White paper on education and training (notice 196 of 1995). Available at http://www.polity.org.za/polity/govdocs/white_papers/educ1.html. Accessed 28 February 2015. [ Links ]

Department of Education 1996. Education white paper 2: The organisation, governance and funding of schools (notice 130 of 1996). Government Gazette, Vol 169(16987), 14 February. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=rX5JM3JBN7A%3d&tabid=191&mid=484. Accessed 1 March 2015. [ Links ]

Francis D & Le Roux A 2011. Teaching for social justice education: the intersection between identity, critical agency, and social justice education. South African Journal of Education, 31(3):299-311. [ Links ]

Fraser N 2009. Social justice in the age of identity politics: redistribution, recognition, participation. In G Henderson & M Waterston (eds). Geographic thought: a praxis perspective. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Freire P 2004. Pedagogy of hope. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Freire P 2007. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Garrett PM 2010. Recognizing the limitations of the political theory of recognition: Axel Honneth, Nancy Fraser and social work. British Journal of Social Work, 40(5):1517-1533. [ Links ]

Goolam NMI 2001. Human dignity - our supreme constitutional value. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PER), 4(1):43-72. [ Links ]

Guba EG & Lincoln YS 2005. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In NK Denzin & YS Lincoln (eds). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Guilherme M & Dietz G 2015. Difference in diversity: multiple perspectives on multicultural, intercultural, and transcultural conceptual complexities. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 10(1):1-21. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2015.1015539 [ Links ]

Hargreaves A & Fink D 2006. Sustainable leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Kurland NG 1997. Foreword. In MD Greany (ed). Introduction to social justice. Arlington, VA: Center for Economic and Social Justice. Available at http://www.cesj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/introtosocialjustice.pdf. Accessed 23 February 2015. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2010. Practical research: planning and design (9th ed). New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

Le Grange L 2007. An analysis of 'needs talk' in relation to sustainable development and education. Journal of Education, 41:83-95. [ Links ]

Leithwood K & Jantzi D 2009. Transformational leadership. In B Davies (ed). The Essentials of School Leadership (2nd ed). London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Mahlomaholo SMG 2011. Gender differentials and sustainable learning environments. South African Journal of Education, 31(3):312-321. [ Links ]

Manning T 2001. Making sense of strategy. Cape Town: Zebra Press. [ Links ]

Marshall C & Oliva M 2010. Building the capacities of social justice leaders. In C Marshall & M Oliva (eds). Leadership for social justice: making revolutions in education (2nd ed). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

Marshall C & Rossman GB 2011. Designing qualitative research (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

McMillan JH & Schumacher S 2010. Research in education: evidence-based inquiry (7th ed). Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Merchant BM & Shoho AR 2010. Bridge people: civic and educational leaders for social justice. In C Marshall & M Oliva (eds). Leadership for social justice: making revolutions in education. Boston, MA: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2009. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Miller D 1999. Principles of social justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Mintzberg H 1989. Mintzberg on management: inside our strange world of organizations. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Mouton J 2001. How to succeed in your master's & doctoral studies: a South African guide and resource book. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Nafukho FM 2006. Ubuntu worldview: a traditional African view of adult learning in the workplace. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 8(3):408-415. doi: 10.1177/1523422306288434 [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuis J 2010. Social justice in education revisited. Education Inquiry, 1(4):269-287. Available at http://www.education-inquiry.net/index.php/edui/article/viewFile/21946/28694. Accessed 28 February 2015. [ Links ]

Potgieter FJ 1980. Historiese wordingskunde. Pretoria: HAUM. [ Links ]

Rawls J 1971. A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. [ Links ]

Rawls J 1999a. Distributive justice. In SR Freeman (ed). Collected papers: John Rawls. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Rawls J 1999b. Justice as fairness: political not metaphysical. In SR Freeman (ed). Collected papers: John Rawls. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Rawls J 1999c. Reply to Alexander and Musgrave. In SR Freeman (ed). Collected papers: John Rawls. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Rawls J 1999d. The independence of moral theory. In SR Freeman (ed). Collected papers: John Rawls. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996a. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (no. 108 of 1996). Available at http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/images/a108-96.pdf. Accessed 28 February 2015. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996b. National Education Policy Act (no. 27of 1996). Government Gazette, 24 April, Volume 370(17118). Cape Town: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996c. South African Schools Act, 1996 (No. 84 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1998. No. 76 of 1998: Employment of Educators Act, 1998. Gazette, 19320 (no. 1245). Pretoria: Government Printers. Available at http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/19320.pdf. Accessed 2 March 1998. [ Links ]

Spaull N 2013. South Africa's education crisis: the quality of education in South Africa 1994-2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development & Enterprise. [ Links ]

Spaull N & Taylor S 2015. Access to what? Creating a composite measure of educational quantity and educational quality for 11 African countries. Comparative Education Review, 59(1):133-165. Available at https://nicspaull.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/spaull-taylor-2015-cer-access-to-what-appendix.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2015. [ Links ]

Starratt RJ 2009. Ethical leadership. In B Davies (ed). The essentials of school leadership (2nd ed). London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Starratt RJ 2012. Cultivating an ethical school. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Stavros JM & Hinrichs G 2009. The Thin Book of SOAR: Building strengths-based strategy. Bend, OR: Thin Book Publishing Company. [ Links ]

United Nations (UN) 2006. Social justice in an open world: the role of the United Nations. The International Forum for Social Development (Economic and Social Affairs). New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

UN 2013. Report of the UN Secretary-General: a life of dignity for all. Available at http://www.un.org/millenniumgo als/pdf/S G_Report_MDG_EN.pdf. Accessed 14 October 2013. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen PC 1991. Perspectives on educational management and explanation of terms. In PC van der Westhuizen (ed). Effective educational management. Pretoria: HAUM Tertiary. [ Links ]

Van Deventer I 2013. Management strategies for effective social justice in education. Unpublished PhD thesis. Potchefstroom: North-West University. [ Links ]

Van Vuuren HJ, Van der Westhuizen PC & Van der Walt JL 2012. The management of diversity in schools - A balancing act. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(1):155-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jijedudev.2010.11.005 [ Links ]