Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433

Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.34 n.3 Pretoria Mar. 2014

The implications of the National Norms and Standards for School funding policy on equity in South African public schools

Raj Mestry; Raymond Ndhlovu

Department of Education Leadership and Management, University of Johannesburg, South Africa rajm@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The government's educational reforms since 1994 have focused on equity and redress. Redressing historical imbalances and achieving equity are fundamental policy mechanisms in attempts to restructure South African education. This aspiration is demonstrated in many education policies including the National Norms and Standards for School Funding (NNSSF) policy. While inequalities in resource allocation from the state have been removed, inequalities persist due to the inability of the state to provide free education to all, parents' inability to pay user-fees, the unavailability of qualified teachers in rural schools and unfavourable learner-teacher ratios. A quantitative research was conducted to investigate the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity in public schools in the Tshwane West District of the Gauteng Province. Based on the three first order factors derived from the first analytic procedure, namely, "The effective financial management", "The management of equity issues" and "Access to educational resources", it was found that despite substantial government interventions in the education system, equity has not been fully realised.

Keywords: access, equity, financial management, funding, inequality, National Norms and Standards, no-fee schools, policy, school fees, social justice

Introduction and background to the research problem

Since 1994, the government's efforts to redress historical imbalances and achieve equity were fundamental policy mechanisms to restructure South African education. Equity reforms in post-apartheid South Africa were intended to equalise funding among provinces, schools and socio-economic groups. This was undertaken through national policies that would direct state funding to public schools. The most significant legislation was the National Education Policy Act (South Africa, 1996b), the South African Schools Act (South Africa, 1996a) and the Employment of Educators Act (South Africa, 1998b). The main themes of the White Paper on Education and Training (South Africa, 1995) also articulated the fundamental principles for transformation, namely open access to quality education and redress of educational inequalities.

Equity and redress have been identified as the operational building blocks for the realisation of social justice in education (Motala & Pampallis, 2002). Diphofa, Vinjevold and Taylor (1999) observed that ushering in the new democracy brought with it not only the restructuring and reshaping of education, but also the development and implementation of a policy framework which aims to provide for the redress of past inequalities and the provision of equitable, high quality and relevant education. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2008) asserts that education transformation in South Africa has been characterised by values of social justice and equity, non-racism and non-sexism, Ubuntu and reconciliation. These aspirations are demonstrated in many education policies, such as no-fee schools, post-provisioning norms, rationalisation and redeployment of educators, exemptions on school fees, financial responsibilities assigned to principals and governing bodies, the National Norms and Standards for School Funding (NNSSF) (South Africa, 1998a) and other pragmatic interventions.

In terms of Section 34 of the South African Schools Act, the state is mandated to fund public schools from public revenue on an equitable basis in order to ensure proper exercise of the rights of learners to education and redress of past inequalities in educational provision. The Act also makes provision for school governing bodies (SGBs) to supplement state funding by way of school fees and fundraising initiatives. To address equity in funding school education, the South African government introduced the NNSSF policy (South Africa, 1998a). The NNSSF policy provides a statutory basis for school funding in that schools are now classified into wealth quintiles and subsidised accordingly. Schools serving poorer communities must receive more state funding than schools serving better-off communities.

The scale of changes in policies such as the NNSSF policy has inevitably placed great stress on SGBs, school management teams (SMTs), teachers and district officials, resulting in a significant disjuncture between policy intention and practice, and a growing divide between what the government expect schools to do and what schools are in fact able to do. Thus, while the intentions of the state to address equity and social justice are laudable, there is a long way to go in achieving good quality education, particularly for marginalised and disadvantaged schools. A number of schools in poor rural and urban working-class communities still suffer the legacy of large classes, deplorable physical conditions and the absence of learning resources, despite a major Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), the National School Building Programme and many other projects paid for directly from provincial budgets (Chisholm, 2005). Yet, teachers and learners in poor schools are expected to achieve the same levels of teaching and learning as their compatriots in wealthier areas. Such contradictions within the same public school system probably reflect past discriminatory investment in schooling and vast disparities in personal income of parents (Ndimande, 2006).

In this regard, Motala (2006:80) emphasises that "while discrimination in physical, human and financial resource allocation has been removed, inequalities persist for a number of reasons, including the ability or inability of parents to pay school fees, the greater unavailability of qualified teachers in some schools, the leadership styles of school managers and unfavourable teacher-learner ratios, especially in township and rural schools, and public schools in general".

It is ironic, given the emphasis on redress and equity by the state, that the funding provisions of the NNSSF policy appear to have worked thus far to the advantage of public schools patronised by middle-class and wealthy parents of all racial groups (South Africa, 1996a; Chisholm, 2005). To close the achievement gap, the educational system should address all pertinent issues so that township and rural learners can fully contribute to, and benefit from, the new democratic nation (Mqota, 2009). Against this background, the research problem for this study was encapsulated as follows: What are the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity in public schools?

Since research is "focused" on different models applied to funding public schools, this study offers a different lens through which to view the concept of state funding in schools and its implications on equity and social justice. We critically examine the concepts of social justice and equity in funding, and explore the experiences and perceptions of teachers and SMTs regarding the state's funding model and how it deals with equity and social justice. This study contributes to this emerging literature and has relevance to international scholars and policy-makers where the education system is characterised by transformation, an emerging economy and scarce resources.

Rationale for this study

The general aim of this study was to investigate the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity in public schools. In order to realise the general aim of this research, the specific objectives were to:

- understand the concept 'equity' in relation to state funding;

- examine the NNSSF policy that addresses equity in school funding;

- determine the perceptions of teachers on the implementation of the NNSSF policy and its implications on equity in public schools; and

- establish how the implementation of the NNSSF can be strengthened to achieve equity in public schools.

Conceptualising Equity in Education

Equity is a "social term rather than an economic one and is defined in relation to inequities or inequalities in the distribution of wealth or resources and the adjustments which are required to allow for more equitable redistribution" (Brown & Tandon, 1983:16). Equity refers to "levelling the playing field" with no group being privileged in a transformed system (Motala & Mungadi, 2000:13). It refers to fairness and justice. Justice may require providing special support to those who were disadvan-taged in the past. Equity is about "providing the right amount of resources that a certain group needs to live a full life, given the historical, material and social marginalisation they have experienced" (Zine, 2001:251). For instance, equality is like allocating the same amount money to all schools. Equity, on the other hand, operates from the premise that the poorest school will be given more money in line with its poverty ranking level. Within an equity framework, we need to understand that forms of social difference are not all the same, but instead require different and disproportionate responses. In other words, oppression does not homogenise groups of marginalised people, but instead "there are significant distinctions between oppressed groups that require different responses" (Zine, 2001:250). To fully understand the concept of equity, we need to differentiate between equity and social justice.

Social justice extends beyond socially just school practices and includes lessons and activities specifically designed to help students consider some causes of, and solutions for, persistent social, economic and political inequities. Ultimately it encourages collective action against such inequities. A socially just approach to education, therefore, strives "to ensure equitable and excellent educational opportunities and outcomes for all learners and is aimed at redressing persistent inequities outside of schools" (Shields & Mohan, 2008:289-300). Equity, on the other hand, is the application of the principle of justice or fairness to correct or supplement the law. This definition gives recognition to the need to redress the past injustices, like discrimination based on race. This implies that equity contains fair discrimination. Equity is further defined as "treating individuals in an unequal manner so as to produce some form of fair treatment" (Crampton, Thompson & Vesely, 2004:1).

UNESCO (2008) po sits that the apartheid education system entrenched gross educational disparities and inequities between different racial groups. The need for rectification and parity in all aspects of education was thus a necessary imperative in a new, democratic system. The demand for rectification was captured in the commitment to equity and redress as cornerstone principles of all educational policies. Equity conceptions deal primarily with variations or relative differences in educational resources, processes and outcomes across children (Baker & Green, 2008). Ladd and Fiske (2008) and Naicker (1996) indicate that some of the more notable input inequities in school-based education were the disparities in the per capita expenditure, the teacher-learner ratios, the qualifications of teachers and physical resource allocation. The Education White Paper 2 (South Africa, 1996c) highlighted these disparities by pointing out that the former racially and ethnically organised Departments of Education embodied substantial inequalities in per capita spending; the largest disparities being accounted for in the 'skewed' distribution of teacher qualifications, inappropriate linking of salary levels to qualifications and disparities in teacher-learner ratios.

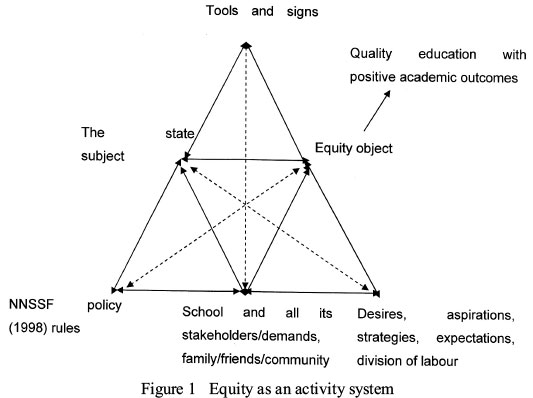

Our theoretical exploration was conducted from an activity theory position. To do this, we drew on Engestrom's formulation of "third-generation activity theory", also called the cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) (Gronn, 2003:85-87), to investigate the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity in public schools. CHAT offers principles that enables researchers to understand and reconstruct an activity system (such as the NNSSF policy) as a unit of analysis; how different and multiple voices at all levels have shaped the implementation of the NNSSF policy and its implications on equity in public schools; how the funding system has emerged and transformed over time; the contestations that have emerged and how they have changed the funding system in different contexts; and finally, how the implementation of the policy can be transformed at the local and national levels. Applying a theoretical framework of this nature, should serve as a useful viewpoint in that the state's obligation to address equity through the NNSSF can be seen not to be only embedded within an activity system, but also continuously influenced by tensions between the other elements of the system (Figure 1). It is our intention to argue that the primary contradiction/tension that echoes through the entire activity system is the distribution of limited state funding to the unlimited wants of all public schools.

According to the South African Schools Act (South Africa, 1996a), the state is required to fund all public schools and the NNSSF policy (South Africa, 1998a) provides a quintile ranking mechanism to address equity in schools. Poor schools ranked Quintile 1, 2 and 3 are declared no-fee schools and are allocated a higher state subsidy than the affluent schools that are declared Quintile 4 and 5. Mestry and Dzvimbo (2011) assert that human subjectivity which develops rules, expectations and norms, such as NNSSF policy, in this conceptualisation is historical, political and ideological. It is not a neutral process but dialectical and gives rise to contradictions and discursive practices that engender transformation and inequity based on race and even types of schools. Furthermore, in the process of transformation, both society (education community) and human subjectivity (imbedded in policy makers and implications of the NNSSF policy) become complex and assume their own philosophical existence which eventually influences major participants in the activity system, such as the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity in public schools.

The NNSSF Policy: An instrument to address equity As mentioned earlier, the NNSSF policy (South Africa, 1998b) promulgates progressive funding by classifying public schools into wealth quintiles and are subsidised accordingly (that is, schools serving poorer communities should receive more funding than schools serving better-off communities). The goal of achieving racial equity and redress has been at the core of attempts to reform expenditure patterns. However, Mestry and Bisschoff (2009:48) emphasise that "poverty targeting takes as its point of departure the assumption that certain groups of learners need more resources than others as a result of economic advantage". Based on statistics, poor schools and learners are persistently disadvantaged and will take much longer to overcome the barriers of the past, thus prolonging the cycle of poor quality education.

The NNSSF policy requires quintiles to be determined nationally. The National Department of Education determines the amount that provinces ought to allocate per learner in each quintile category and this is published annually in the Government Gazette (South Africa, 1998a). The amount allocated for recurrent costs using the 'Resource Targeting Table' is based on the principles governing the determination of the school poverty or quintile ranking and this includes: the relative poverty of the immediate community around the school, which, in turn, should depend on individual or household advantage or disadvantage with regard to income, wealth and level of education; and data from the national Census conducted by StatsSA or any equivalent data set that could be used as a source (Gauteng Department of Education, 2006; Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009).

The poverty score of each school assigns it to a quintile rank which, based on a predetermined formula, governs the amount of funding each public school receives; and thus serves as a pro-poor mechanism used to determine the amount of funding for each school. Quintile 5 represents the least-poor schools and quintile 1 the poorest schools. In order to have an equitable distribution of resources while operating with limited financial resources, it required each Provincial Education Department (PED) to direct 60% of their non-personnel and noncapital recurrent expenditure towards the most deprived 40% of schools (quintile 1 and 2) in their provinces. On the other hand, the least disadvantaged 20% of schools (quintile 4 and 5) should only receive 5% of the resources (Giese, Zide, Koch & Hall, 2009). It would appear that "only the poorest schools were targeted and those schools located in the middle of the resource targeting table, the so-called middle schools (quintile 3), become neglected and impoverished" (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009:48). However, more recently the PEDs provide quintile 3 schools the opportunity to be declared 'no-fee schools' so that the financial burden of these schools can be alleviated.

The NNSSF policy (South Africa, 2006; South Africa, 2008) can thus be regarded as an equity instrument that aims at distributing the bulk of recurrent non-personnel expenditure to poorer schools based on the assumption that such an approach will lead to improved performance and the provision of quality education. Bush and Heystek (2003) state that, since the

NNSSF's implementation in 2000, previously disadvantaged schools in townships and rural areas received larger departmental budgets than advantaged schools in inner-cities and suburbs. Motala (1998:8) observes that for the "first time school funding and poverty is now related, both in terms of the paucity of school resources and the socio-economic status of the community in which the school is located". The NNSSF policy aims to improve the quality of education by not only redistributing resources, but also by redistributing the conditions of learning so as to increase the possibility of attaining cognitive equity amongst all learners in South Africa (South Africa, 1998a).

However, addressing redress and equity, the NNSSF policy acknowledges that existing funding provisions allow SGBs to improve the quality of education by raising funds for additional staff and facilities (South Africa, 1998a). Bush and Heystek (2003:130) note:

"This approach is justifiable to address historic inequalities but it also increases pressure on the SGBs of the schools in quintile 4 and 5 to replace the lost income through fees or other fundraising activities. The outcome is substantial variations in fee levels at different schools, making it more difficult to achieve the goals of equity. The richer schools are able to protect their privileged position through high fees while the positive discrimination in state funding cannot compensate for the substantial differences in fee levels."

Methodology and Research Design

The quantitative research method was chosen for this study. Quantitative research is an inquiry into social or human problems "based on testing a theory composed of variables, measured with numbers and analysed with statistical procedures, in order to determine whether the predictive generalizations of the theory hold true" (Creswell, 2008:2). Unlike qualitative researchers, those who engage in this form of inquiry have assumptions about testing theories deductively, building in protections against bias, controlling for alternative explanations, and being able to generalize and replicate the findings. This study aims to investigate how the state addressed equity in public schools through the NNSSF policy.

A quantitative study, using a survey consisting of two sections, was used to answer the research question. Section A included 13 questions that were designed to elicit biographical information from the respondents. Section B consisted of 45 items that probed the perceptions of respondents regarding the implications of the NNSSF policy on equity. These items were constructed and compiled, based on key factors which had been prioritised during the literature review on public school funding and equity. The closed-ended items were designed to garner the views of teachers and school managers as to how schools were funded and how these funds were disbursed in the quest for quality education. The questionnaire further differentiated between fee-paying schools and no-fee paying schools and also, schools having section 21 functions and schools without section 21 functions. Items B10 to B13 were answered by respondents from fee-paying schools while items B14 to B17 were answered by respondents from 'no fee' paying school. In addition, items B36 to B40 were answered by respondents from non-section 21 schools and items B41 to B45 were answered by respondents from section 21 schools.

Section B was subjected to statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 15 (Norusis, 2010). Teachers and school managers were required to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements concerning the NNSSF policy and its implications on equity in their respective schools based on a six-point Likert scale. All the scale points were labelled ranging from 1 ("Strongly Disagree") to 6 ("Strongly Agree").

A random sample of 80 public schools comprising 40 primary schools and 40 secondary schools was drawn from a population of 123 schools in the Tshwane West District. Respondents were chosen from various post levels in the teaching profession. It was felt that the perception of teachers at various post levels relative to school funding could vary and hence it was important to sample as wide a range of post levels as possible. A total of 480 questionnaires were handed out to teachers and SMT members at these schools and personally collected by the researchers. Using purposive sampling, six questionnaires were distributed to each school as follows: the principal, one head of department and four post level one teachers. We requested that principals assist in selecting heads of department and teachers with at least five years' teaching experience to complete the questionnaire.

The ethical considerations for conducting this research were carefully considered and respondents were duly informed that they could withdraw at any time from the study without any reprisals. They were also assured of their anonymity and were informed that their dignity, privacy and welfare would at all times be respected. The questionnaires were distributed and collected by the researchers themselves. A total of 358 questionnaires (74.6%) were received. This represented a high return rate, which enabled us to draw valid and reliable conclusions.

The questionnaires were sent to the Statistical Consulting Services at the University of Johannesburg, where the data were transcribed and processed. This study made use of both descriptive and inferential statistical analysis strategies. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means and standard deviations were used to describe the study sample. Inferential statistics were performed using SPSS 15 programme to identify a number of factors that may facilitate the processing of the statistics (Norusis, 2010).

Data Analysis and findings

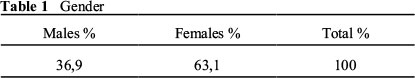

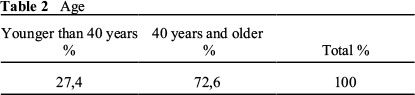

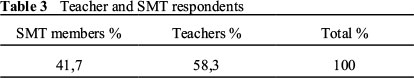

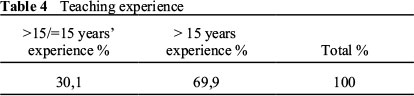

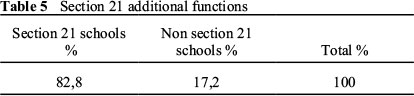

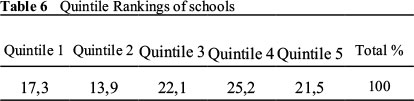

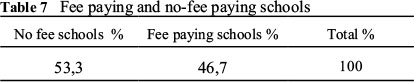

Selected biographical details in Section A of the questionnaire are illustrated in Tables 1 to 7:

The public ordinary schools sector in the Gauteng Province has a female to male ratio of 71:29 for all teachers who are state-paid. In this study there were more female teachers (63%) than male teachers (37%) (Table 1).

Table 2 reflects that about 73% of teacher and SMT respondents were older than 40 years.

School Management Teams (SMTs) refer to heads of department, deputy principals and principals (Gauteng Department of Education, 2011). When analysing data by post levels, about 58% selected were teachers and 42% were SMT members (principals - 8%; deputy principals - 10%; and heads of department - 24%).

Table 5 refers to section 21 of the South African Schools Act (South Africa, 1996a) which states that public schools that have financial expertise and governance capacity may apply to the Head of Education (HOD) of the PED for additional functions such as maintaining and improving school property; purchasing textbooks and educational materials; and paying for repairs and maintenance of school buildings. "These schools enjoy the benefits of selecting their own suppliers, negotiating better prices and discounts, determining the delivery dates for essential goods and services; and taking control over the utilisation of state funds deposited into the schools' banking accounts" (Mestry & Bisschoff, 2009:23). In the Tshwane West District, a large number of schools (82,8%) prefer to have control over the school funds and therefore applied for additional functions in terms of section 21 of the South African Schools Act, 1996.

Tables 6 and 7 refer to the quintile ranking and funding status of selected public schools. Using a national quintile system, schools are ranked according to the poverty index of the community (South Africa, 1998a). Poor schools (also referred to as no-fee schools), ranked either as quintile 1, 2 or 3, receive substantial subsidies per learner for educational resources from the PED, whereas affluent schools ranked quintile 4 or 5 receive far less funding from the state. It is interesting to note that in this study, all schools that were ranked Quintile 3 opted to be declared no-fee paying schools.

From the above information, it can be established that the respondents and schools that formed part of this study provided a reasonably representative profile of public schools in the Tshwane West District of the Gauteng Province.

In Section B, factor analysis was used to establish the relevant factors needed to facilitate the analysis of the data. This involved subjecting the 45 items which made up Section B of the questionnaire to principal axis factoring (PAF). Prior to performing PAF, the suitability of data for factor analysis was assessed. A cross tabulation indicated that items B10 to B17 were poorly answered as respondents answered items they were not supposed to. In addition, a reliability analysis of items B10 to B13 and items B14 to B17 indicated low reliability coefficients and were consequently omitted from the final differential analysis.

A factor analytic procedure on items B1 to B9 and B18 to B33 resulted in a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.873 and a Bartlett's sphericity value of p = 0.000 indicating that a factor analytic procedure was appropriate in reducing the number of variables to a more suitable number. Furthermore a Monte Carlo PCA (Principal Component Analysis) for Parallel Analysis (Pallant, 2007) indicated that the three first-order factors would be sufficient. Consequently a varimax rotation with three forced factors indicated that these factors explained 49.92% of the variance present. On performing a second-order PCA on the three first-order factors with varimax rotation only one factor which explained 63.73% of the variance present was produced. This factor was named "The effective management and governance of school resources". However, as the three first-order factors had reliability coefficients greater than 0.7 it was decided to use these three factors in the statistical analysis. "The effective management and governance of school resources" is thus composed of these three first-order factors. The items and the names provided for these three first-order factors are given in Tables 8 to 10.

The data in Table 8 indicate that the respondents agree (ẍ = 4.33) with the items contained in the factor. The distribution of the data is slightly negatively skew.

The analysis of this factor reveals a perception that most SGBs are managing their schools' funds and physical resources effectively and efficiently. They have well-functioning finance committees that have a good understanding of the process of budgeting and how to supplement the schools' funds through various fundraising efforts.

The data in Table 9 indicate that the respondents partially disagree with the factor 'Management of equity issues' (ẍ = 3.42). The distribution of the data is normal.

The low mean scores of items grouped under this factor reveal that both groups, SMTs and Teachers, are of the opinion that PEDs are not providing poorer schools with sufficient funds to procure resources and therefore not adequately addressing equity. By implication, parents should not carry the burden of providing additional funds to the schools. The state should take full responsibility to provide resources to public schools (see low mean scores of 2.86 and 3.86 in B1 and B6, respectively).

The data in Table 10 indicate that the respondents partially disagree with the factor "Access to educational resources" (ẍ = 3.36). The distribution of the data is normal. To provide quality education, most SGBs of affluent schools ensure that sufficient physical and human resources are available. However, the low mean scores for items B24, B33, B32 and B30 reveal that even though more funding is provided to poor schools (Quintile 1, 2 and 3), these schools cannot afford to appoint additional teachers above the norms set by the Department of Education, and still lack laboratory and library resources.

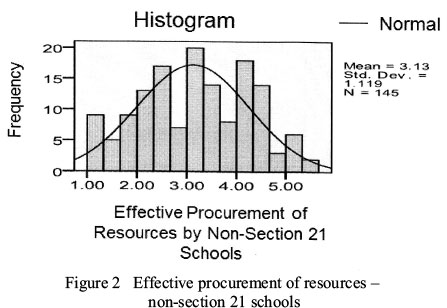

A factor analytic procedure was also performed on items B34 to B40. Item B34 had a measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) of 0.7 and was removed from the factor analysis (Field, 2009). The KMO was 0.767 and the Bartlett's sphericity was p = 0.000 indicating that a factor analytic procedure would further reduce the number of variables. One factor (Figure 2) resulted which had a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.84 and was named 'The effective procurement of resources by non-section 21 schools'.

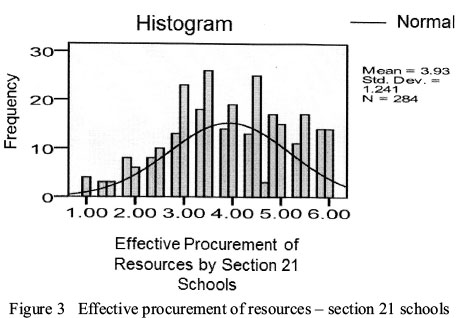

Items B41 to B45 were also subjected to a factor analytic procedure. Item B43 had a communality value < 0.3 (Field, 2009:637) and was removed from the factor analysis. The remaining items had a KMO of 0.78 and Bartlett' sphericity of p = 0.000 indicated that a reduction of variables was likely. One factor (Figure 3) which explained 62.76% of the variance and a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.79 resulted. It was named 'The effective procurement of resources by section 21 schools'.

We will now analyse the hypotheses for the first order factors that were formulated in respect of all the independent groups. The comparison of two independent groups will be the first to follow.

Comparison of SMTs and Teachers with regard to factor means Before proceeding with any parametric tests (t test or ANOVA) the underlying assumptions were checked: For normality, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test was used; and for equal variance the Levene's t test was applied. If the variances are similar (p > 0.05) then equal variances are assumed and if they are significantly different (p < 0.05) then equal variances are not assumed. In both cases the p value was greater than 0.05 and the assumptions were then deemed to be met.

The appropriate hypotheses will firstly be provided for only two of the groups, namely, "Present position occupied by respondents" and "Quintile rankings of schools" where significant differences were found.

The hypothesisis stated as follows: There is statistically no significant difference between the factor means of the two present post-level groups: School Management Teams (SMTs) and Teachers with respect to the factor means.

The data in Table11 indicate that only the hypothesis of FB1.2, "The management of equity issues" cannot be rejected. With respect to FB1.2 both groups, the SMTs and Teachers, partially disagree with the factor but they do not differ significantly from one another. The SMT and Teacher groups are of the opinion that it is imperative for the state to deal with the management of equity issues by providing more resources to poorer schools than to affluent schools, so that poorer schools can be given the opportunity to provide quality education to learners.

With respect to the factor "The effective financial management by the SGB (FB1.1)", both groups partially agree but the SMT group agrees to a statistically significantly greater extent than do the Teacher group. As principals are ex-officio members of the SGB and deputy principals and Heads of Education (HODs) are likely to be part of the financial committee of the school, one would expect them to agree more strongly with the factor of effective financial management. Also, the SMTs are directly involved in handling the school's physical resources and play a more prominent part in the budgeting process than do Teachers. They thus have an obligation to ensure that the SGB manages the school's finances effectively. The effect size is moderate r = 0.31) indicating the importance of this finding.

Regarding the factor "The access to educational resources (FB1.3)", both groups, the SMTs and Teachers partially disagree with this factor but Teachers tend to disagree to a larger extent than do the SMTs. Teachers, especially in poorer schools, are of the opinion that inadequate physical resources are supplied by the Department of Education to their schools and that they experience extreme difficulty in sharing or accessing physical resources for them to be able to teach effectively. However, the SMTs believe that since the introduction of the NNSSF policy, teachers have been provided with sufficient re- sources in their schools. The effect size is small (r = 0.24) indicating that accessing educational resources is dependent on the efficiency and effectiveness of the SMTs in the management of resources.

The SMTs partially agree with the factor "Effective procurement of resources by section 21 (FS.21) schools" while Teachers partially disagree with this factor. Section 21 schools are allowed to procure resources for themselves and it is expected that the persons involved with the procurement of resources will do it as effectively as possible. It thus seems as if the relative independence regarding financial management, which allows section 21 schools to negotiate with suppliers of resources, leaves them with a more positive perception and provides them with greater financial autonomy. Most of the section 21 schools employ additional administrative clerks who take on the responsibility of effectively managing the procurement of resources for their schools. However, in poorer schools, this function is handled by the SMTs or teachers and they are unable to manage the procurement of resources efficiently. Thus, Teachers partially disagree with this factor.

The SMTs partially agree with the factor "Effective procurement of resources by non-section 21 (FNS.21)" schools while Teachers partially disagree with this factor. Schools that do not apply for additional functions in terms of section 21 of the South African Schools Act receive a paper budget from the Department and they are not able to negotiate best prices for the procurement of resources. Most schools delegate the procure- ment function to the SMT since they are involved in the management of physical assets and the budgeting process. However, in many poorer schools (non-section 21 schools), where SMTs carry a heavy workload, they are unable to employ more teachers than those provided for in the post provisioning norm set by the Department or to procure resources effectively and efficiently. Therefore, Teachers partially disagree with this factor that the procurement of resources is managed effectively. SMTs in Section 21 schools thus have the perception that they manage the procurement of resources effectively when compared to non-section 21 schools. The medium effect size (r = 0.38) furthermore indicates the importance of this finding. We will now analyse the quintile groupings of schools.

Comparison of quintile groupings with regard to factor means The hypothesis is stated as follows: There is no significant difference between the factor means of the two present quintile ranking groups: Poor schools (Q 1+2+3) and Affluent schools (Q 4+5) with respect to the factor means.

The data in Table 12 indicate that only FNS21 cannot be rejected. Although both quintile groupings partially disagree with the factor "Effective procurement of resources by non-section 21 schools", they do not differ significantly and the result could be due to chance factors.

Regarding the "Effective financial management by the SGB", respondents from the affluent schools belonging to quintiles 4 and 5 tend towards agreement with the factor, while respondents from the poorer schools in quintiles 1, 2 and 3 partially agree with the factor. The effect size is moderate (r = 0.32) and indicates the importance of this finding.

With respect to "The management of equity issues" the affluent schools disagree to a greater extent than do the poorer schools. This is the only factor where the affluent schools have a lower factor score than the poorer schools. These schools are affected by the state's policy to address equity issues especially in funding poorer schools substantially. Affluent schools receive a smaller financial grant from the government than do quintile 1, 2 and 3 schools and thus have to rely on school fees and fundraising events to ensure that learners are provided with quality education. It is interesting to note that even though the poorer schools are significantly subsidised by the state, learner performance as reflected in the Annual Assessment (ANA) results and Senior Certificate Examinations (Grade 12) results has not improved substantially in these schools, whereas the affluent schools (quintile 4 and 5) are subsidised far less than the poorer schools but learner performance in most of these schools is very good to outstanding.

Comparison of three or more independent groups

We made use of the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test when we tested three or more independent groups for possible significant differences. Once differences were found among all three groups taken together, post-hoc tests were used to make a pair-wise comparison. We will discuss two independent but closely related variables, namely "Age" and "Teaching experience" in this section.

Age of respondents

The data in Table 13 indicate a direct association between the two factors involved and the age of the respondents. It seems as if the older the respondents are the more strongly they agree with the factor "Effective financial management" and "The effective procurement of resources by section 21 schools". This could possibly be a result of most of the teachers who fall into the age group 47-52 and 53+ being victims of the apartheid era who had very little knowledge of and experience in the management of school finances, or even in the procurement of resources, and would therefore hope that the finances and resources are managed effectively.

With respect to the factor "Effective procurement of resources", quintile 4 and 5 schools agree with this factor to a significantly greater extent than do quintile 1, 2 and 3 schools.

The data in Table 13 indicate a directly proportional relationship between the factor "Effective financial management by the SGB" and teaching experience of respondents. The teachers with 27 or more years of experience differ significantly from each of the lower age groupings and agree more strongly with "effective financial management by the SGB". If one considers that they may have started their teaching career at around 24 years of age, this would place them in the category of 50 years or older. This finding thus corroborates the finding with respect to age as a cross tabulation also indicates that 24.6% of the respondents who had 27 or more years of experience also fell in the category of 53 years or older. The effect size (r = 0.30) is moderate reflecting the importance of this finding.

The mean scores obtained by the various age groups also follow a direct proportion. The respondents with most teaching experience differ statistically significantly from each of the other age groupings. The older respondents with more teaching experience (exceeding 20 years) tend to agree more strongly with the factor "The effective procurement of resources by section 21 schools" than respondents with less teaching experience (less than 20 years). Section 21 schools have been in existence for less than 27 years and this indicates that these respondents probably believe that the procurement of resources is more effective now than it was in the previous dispensation.

The older and more experienced teachers from historically disadvantaged communities never had the opportunity to use effective or valuable resources in their teaching and with the advent of the NNSSF policy; poorer schools are provided with additional funding to procure physical resources. The provision of more financial and physical resources to poorer schools is intended to have an impact on the provision of quality education. They will thus agree with the factors "Effective financial management" and "The effective procurement of resources by section 21 schools". The effect size (r = 0.25) is however, small.

Conclusions and recommendations

There is compelling evidence to show that the state is making concerted efforts to address social justice and equity in public schooling. The South African Schools Act and the NNSSF policy are landmarks that not only ensure access for poor learners to public schools, but also ensure that substantial funding is provided to all poor schools. This is consistent with CHAT theory which underpinned this study. The NNSSF policy prescribes that schools be ranked into quintiles where quintile 1, 2 and 3 are declared no-fee schools and are provided with substantial funding, and quintile 4 and 5 schools are affluent schools where state funding has been significantly reduced. However, these initiatives are not enough to address the improvement of educational outcomes and learner achievement, especially for rural, poor and illiterate children. Even though state funding has been reduced, affluent schools are able to acquire physical and human resources to provide quality education through various fundraising initiatives and the collection of school fees from parents.

Although it is well intended, the NNSSF policy has not achieved its goal of redressing the imbalances in education of the past, nor has it succeeded in achieving equity (in terms of education and resources) at both primary and secondary public schools. The main stumbling block appears to be the way schools employ funding provided by the PEDs. Most of the poorer schools have not applied for additional functions in terms of section 21 of the South African Schools Act and therefore depend on district offices to manage their state funding. PEDs allocate substantial funding to poor schools, but HODs in the provinces restrict SGBs from spending the funds according to the needs of the schools. Instead, each year the HODs send out directives to schools in their province prescribing that the funds should only be utilised for learning and teaching support materials, repairs and maintenance of school property, and for the payment of services such as water and electricity. We advocate that SGBs should be trained in financial management so that they will have the requisite knowledge and skills to make informed financial decisions for school improvement. These SGBs would be empowered to self-manage the school's funds.

There is a move to abandon the quintile system of public school funding. Ironically, state funding to poorer schools has increased substantially but the provision of quality education and improvement in learner performance has not been forthcoming. The opposite is true for affluent schools. We believe that schools should be funded based on their essential needs and the socio-economic status of parents attending the school rather than the poverty index of the community where the school is located. This will eliminate the problem of funding schools in affluent areas serving poor learners from outside the surrounding area of the school. For example, even though a school is situated in an affluent area, it may have over 90% of its learners from outside its feeder area. This school is ranked as quintile 5 and receives the lowest funding on the scale, yet caters mainly for middle class and poor learners. These schools are thus placed in a diabolical situation: They raise school fees and then adopt a hard-line approach to grant exemptions to learners who have difficulty in paying these exorbitant fees. Similarly, learners from affluent circumstances may attend no-fee schools without having to make any monetary contribution.

Social justice and equity can only be achieved if the state makes more funds available for learners to access education and to reduce or abolish structural forms of oppression that restrict peoples' access to resources and opportunities for exercising and developing their capabilities.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) for funding the research project, and Prof BR Grobler for assisting with the statistical analysis.

References

Baker BD & Green PC 2008. Conceptions of Equity and Adequacy in School Finance. In HF Ladd & EB Fiske (eds). Handbook of research on education finance and policy. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brown LD & Tandon R 1983. Ideology and Political Economy in Inquiry: Action Research and Participatory Research. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 19(3):277-294. doi: 10.1177/002188638301900306 [ Links ]

Bush T & Heystek J 2003. School Governance in the New South Africa. Compare, 33:127-138. [ Links ]

Chisholm L 2005. The State of South Africa's Schools. In J Daniel, R Southall & J Lutchman (eds). State of the Nation (2004-2005). Pretoria: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Crampton FE, Thompson DC & Vesely RS 2004. The Forgotten Side of School Finance Equity: The Role of Infrastructure Funding in Student Success. NASSP Bulletin, 88(640):29-52. doi: 10.1177/019263650408864004 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2008. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Diphofa M, Vinjevold P & Taylor N 1999. Introduction in getting learning right. Palgrave: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Field A 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Gauteng Department of Education (GDE) 2006. Circular No 56. Johannesburg: Gauteng Department of Education. [ Links ]

Gauteng Department of Education (GDE) 2011. Annual Report, 2010/2011. Available at http://www.education.gpg.gov.za/Document5/Documents/ANNUAL%20REPORT%202010-2011.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2013. [ Links ]

Giese S, Zide H, Koch R & Hall K 2009. A study on the implementation and impact of the No-Fee and Exemption policies. Cape Town: Alliance for Children's Entitlement to Social Security. [ Links ]

Gronn P 2003. The new work of educational leaders: Changing leadership practice in an era of school reform. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Ladd HF & Fiske EB 2008. Education Equity in an International Context. In HF Ladd & EB Fiske (eds). Handbook of research on education finance and policy. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mestry R & Bisschoff T 2009. Financial School Management Explained (2nd ed). Cape Town: Kagiso. [ Links ]

Mestry R & Dzvimbo KP 2011. Contestations of educational transformation: A critical analysis of how the norms and standards for funding are intended to achieve social justice and equity. Journal of Educational Sciences. Special Issue, 2011:9-29. [ Links ]

Motala S 1998. Reviewing Education Policy and Practice: Constraints and Responses. Quarterly review of education and training in South Africa, 5(5):69-75. [ Links ]

Motala S 2006. Education resourcing in post-apartheid South Africa: The impact of finance equity reforms in public schooling. Perspectives in Education, 24(2):79 -94. [ Links ]

Motala S & Mungadi R 2000. From policy to practice: Achieving quality education in post-apartheid South Africa. South African Review of Education, 5:7-31. [ Links ]

Motala E & Pampallis J (eds.) 2002. The State, Education and Equity in Post-apartheid South Africa: The Impact of State Policies. Burlington, NC: Ashgate Publishing. [ Links ]

Mqota V 2009. Education and democracy: A view from Soweto. Montclair: Mqota Publishers. [ Links ]

Naicker I 1996. Imbalances and inequities in South African education: A historical - educational survey and appraisal. MEd Thesis. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Ndimande B 2006. Parental Choice: The Liberty Principle in Education Finance. Perspectives in Education, 24(2):143-158. Norusis MJ 2010. SPSS 15 professional statistics. Chicago: SPSS Inc. [ Links ]

Pallant J 2007. SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Shields CM & Mohan E 2008. High quality education for all students: Putting social justice at its heart. Teacher Development, 12(4):289-300. [ Links ]

South Africa 1995. White Paper on Education and Training. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996a. The South African Schools Act. No. 84 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996b. National Education Policy Act. Act. 27 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1996c. Education White Paper 2: The organisation, governance and funding of schools. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1998a. National Norms and Standards for School Funding. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 1998b. Employment of Educators, Act Number 76 of 1998. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2006. Amended National Norms and Standards for School Funding. Government Gazette, 29179(869). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

South Africa 2008. Amended National Norms and Standards for School Funding. Government Gazette, 31496(1087). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2008. Overcoming Inequality: why governance matters. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2009. London: Oxford University Press. Available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001776/177683e.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2014. [ Links ]

Zine J 2001. Negotiating equity: The dynamics of minority community engagement in constructing inclusive education policy. Cambridge Journal of Education, 31(2):239-269. [ Links ]