Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Education

versión On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versión impresa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.34 no.2 Pretoria jun. 2014

Comparison of educational facilitation approaches for Grade R English Additional Language learning in rural Mpumalanga

P Moodley; A Kritzinger; B Vinck

Department of Communication Pathology, University of Pretoria pat.moodley1@gmail.com; p.moodley@education.mpu.gov.za

ABSTRACT

The Early Childhood Development Manager in Mpumalanga is faced with the problem of providing evidence-based guidance of the best facilitation approach in the Grade R context. An investigation on the effect of facilitation, i.e. play-based or formal instruction, on Grade R performance scores in English Additional Language (EAL) learning was conducted. Literature findings attest to formal learning contributing to better performance scores than play-based learning, yet most rural schools in Mpumalanga use the play-based approach. The English Language Proficiency (ELP) standards assessment tool is reported to have no cultural bias and was used to collect the data. The tool assessed learners' listening and speaking skills in EAL. A quantitative methodology was followed, using a static two-group comparison design. Participants in the two groups were matched according to age and all had a similar exposure period to EAL learning, a rural upbringing, poverty level, and all were mainstream learners. Inter-rater reliability was obtained since two raters assessed learners' proficiency in EAL skills. A one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the data. It was found that the formal based approach contributed to better EAL scores when compared to the play-based approach. Implications for practice are discussed.

Keywords: EAL learning; ELP standards assessment tool; formal instruction; Grade R facilitation; learners' first language; play-based approach

Introduction

The cutting edge debate that has dominated new thinking in the Grade R sector is whether the play-based approach or formal instruction is best to be adopted in the classroom (Burchinel, 2009). This debate resonates emanates from national discussions on the analysis of the Annual National Assessments that were -written by Grade 1 learners in 2011 and 2012 (Department of Education, 2012). Grade 1 learners performed poorly in literacy assessments which were conducted in English (Department of Education, 2012). The school readiness of these learners for formal learning was questioned and debated by educational stakeholders both at national and provincial level (Mpuma-langa Department of Education, 2012). There appears to be a paucity of research on facilitation approaches on Grade R EAL learning. This article focuses on addressing the research gap by investigating which facilitation approach is the best for Grade R EAL learning in a specific context. Although it is acknowledged that a child learns best in his/her first language (Ellis, 2008; Wally, 2007; Xu, 2010), the emphasis placed on English as the language of learning and teaching is characterizing education globally and its impact is also evident in the South African education system.

A brief exposition of the play and the formal instruction approaches will be provided. In formal instruction Grade R classes learners are taught to read and write and the emphasis is on recitation and memorization of letters of the alphabet (Ward, 2008). Discrete language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing) are developed by direct instruction (Geva, 2000). The teacher assumes that children have no prior knowledge or experiences of the new topics or skills introduced in the classroom. In these classrooms teachers usually help children acquire the academic language register, or Cognitive Acquired Language Proficiency (CALP) by discussing the language and content used in texts. CALP refers to learners' ability to demonstrate problem solving, analytical and abstract thinking in the classroom (Cummins, 2008). The formal instruction method may facilitate explicit EAL learning and the play-based approach, implicit or indirect learning (Patterson, 2008). Formal instructional learners may achieve academic language whereas play based learners may only stay at the social language level (Xu, 2010). With formal instruction, learners are expected to demonstrate EAL skills in the classroom based on teachers' request or instructions. Learners are taught the academic language since they are exposed to instructional methods involving context embedded and cognitively demanding tasks (Cummins, 2008). In contrast, during the play-based approach the learner is expected to demonstrate conversational skills, invoke real-work applications and show that there is more than one right answer (Mesthrie, 2006). It may appear that not only Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) are achieved, but that some measure of CALP may also be possible in the play-based approach. BICS refers to children's ability to speak a language for conversational purposes, articulate their views, request information and respond to questions posed by people (Cummins, 2008). Conversational fluency is acquired through face-to-face conversations, and high frequency vocabulary and simple grammatical constructions are used in play-based classes (Geva, 2000).

The South African Constitution, South African Schools Act (Department of Basic Education, 2002) and the Language in Education Policy (Department of Basic Education, 1997) afford learners the right to receive education in the language of their or their parents' choice (Kapp, 2004; Mesthrie, 2006). The official policy of the Department of Basic Education is that Grade R learners need to be facilitated and assessed by teachers in their first language (Department of Basic Education, 1997). However, an analysis of school support visit reports submitted by departmental officials in Mpumalanga attest to Grade R learners being facilitated in English instead of their first language in the rural areas (Mpumalanga Department of Education, 2012). Parents preferred their children to learn in English and it is the only common language in a multilingual context in South Africa (Du Plessis & Louw, 2008; Nel & Müller, 2010). Since English is introduced in rural schools in Grade R, it is an advantage that learners will have some knowledge of EAL skills that is needed for Grade 1 learning. The disadvantage of second language learning is that attrition of first language learning occurs when children want to communicate only in English (Patterson, 2008).

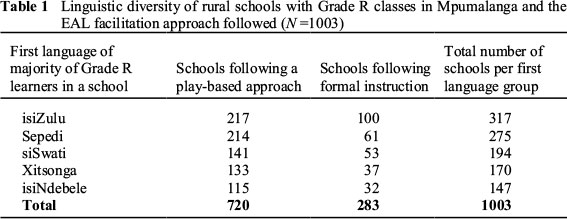

In the beginning of the current study it was important to determine which educational facilitation approaches are implemented in most schools and obtain a picture of learners' first language profile in Mpumalanga. The linguistic diversity of rural schools in Mpumalanga and the EAL facilitation approach used in the different schools are captured in Table 1. The data on the first language of the majority of Grade R learners in a school were obtained from school records, the class teachers and school visit reports compiled by Early Childhood Development (ECD) officials in 2012. ECD officials are responsible for monitoring and supporting Grade R curriculum implementation in schools. Data on the educational facilitation approach (play-based or formal instruction) was obtained through analysis of school visit reports compiled by ECD officials.

According to Table 1 schools are indicated in descending order of language prevalence, with isiZulu the first language of most learners and isiNdebele the least frequent first language of rural Grade R learners in Mpumalanga. The play-based approach is by far mostly used by teachers to facilitate EAL learning in the classroom. The average number of learners per Grade R classroom was found to be 24, which is lower than the maximum number of 30 Grade R learners allowed in the classroom (Department of Education, 2012). With five different first languages spoken by the majority of Grade R children attending rural schools, it was important to obtain evidence for the best EAL facilitation approach to be used.

The ELP standards assessment tool United States (US Department of Education, 2007) was used as a measuring instrument in the study since there is no standardized tool for measuring EAL learning in South Africa. This tool was adapted to the rural Mpumalanga context, ensuring that Grade R learners would be afforded opportunities to demonstrate their EAL skills without any cultural and religious impediments.

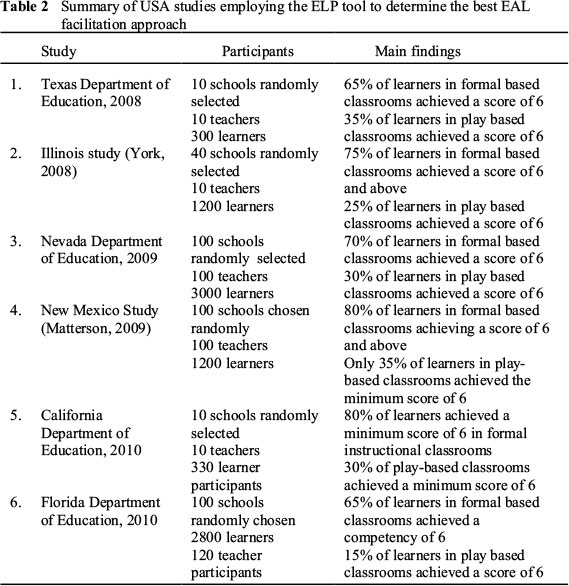

Studies on the use of the ELP tool to assess learners' EAL skills are summarized in Table 2. The studies were also selected to provide a review of research on the best facilitation method for EAL in Grade R. All the studies used a quantitative two-group comparison design. The total score in the ELP tool is 11. The maximum speaking score is seven and the maximum listening score is four. A score below six indicates that the learner is not competent in demonstrating EAL skills whilst a score of six and higher indicates that a learner is competent (US Department of Education, 2007).

According to Table 2 it appears from these large research studies that learners in formal instruction classrooms performed better than learners in play-based classrooms. Based on the numerous studies cited in Table 2 it appears that the ELP is used successfully in research. Further investigation revealed that the ELP is also used as an EAL assessment tool in 25 of the federal states in the US (US Department of Education, 2007). The tool was deemed appropriate for use in a multi-cultural Mpumalanga context since it is reported to be free of cultural bias.

An empirical investigation was now conducted to determine whether the play-based or formal instruction approach is the best approach to facilitate EAL learning to Grade R learners in Mpumalanga's rural schools. As already indicated in Table 1 teachers in rural schools facilitate either the play-based or formal instruction approach in the classroom. The aim of the study was to determine the effect of facilitation (main independent variable) on Grade R performance scores (dependent variable) in EAL learning. It would be valuable to compare learners' listening and speaking scores in both facilitation approaches to determine which approach is the best for EAL learning in Grade R. It should be borne in mind that listening is a precursor to speaking competencies (Wally, 2007).

Method

Research design

A static two-group comparison research design was used. The advantages of the design is that the researcher can clearly identify the best facilitation approach based on the available research data of two groups and make sound recommendations after analysing the data. This design enables the researcher to identify differences within and across the groups at one point in time (York, 2008). Schools with Grade R classes were categorized into either the play-based or the formal instructional groups according to ECD officials' school visit reports. Schools were selected according to the five most prevalent first language groupings of the learners (siSwati, isiZulu, isiNdebele, Sepedi and Xitsonga) as indicated in Table 1. The performance scores of the ELP standards assessment tool (total, listening and speaking) were compared across each language category in both the play based and formal instruction based schools to determine which approach contributed best to EAL scores. All participants had the same duration of EAL exposure in their Grade R classrooms when they were assessed in May 2012. There were no variables manipulated in this study.

Research ethics

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria and the Mpumalanga Department of Education to conduct the study. All teacher participants and the parents of Grade R learners gave written informed consent to participate in the study. The child participants gave assent to partake in the study.

The sample

Research was conducted in 10 rural schools in Mpumalanga. One school from each language category (see Table 1) in both the play-based and formal instruction approaches was randomly chosen from the total of 1003 rural schools. Thus five schools with the different language categories in the play-based approach were matched with five other schools in the formal instruction category. There were a total of 175 Grade R learners and 10 teachers in the study sample. Learner participants were matched according to age, similar exposure period to classroom EAL learning, similar rural upbringing, culture, poverty level and according to the following exclusion criteria.

Learners who had low birth weight and special needs were excluded from the study. These learners are known to encounter challenges in acquiring language skills especially in the formative years and are also reported to be at risk of difficulties with second language acquisition (Ellis, 2008 ; Ward, 2008). Ward (2008) found that in two schools, all Grade R learners with low birth weight performed poorly in language assessments. These findings were also similar to research conducted by Patterson (2008) in one school in California where three learners with low birth weight and two learners with hearing impairment encountered challenges in demonstrating listening and speaking skills. Therefore learners with low birth weight and special needs were not assessed in EAL learning, based on findings emanating from Ward (2008) and Patterson's (2008) research studies.

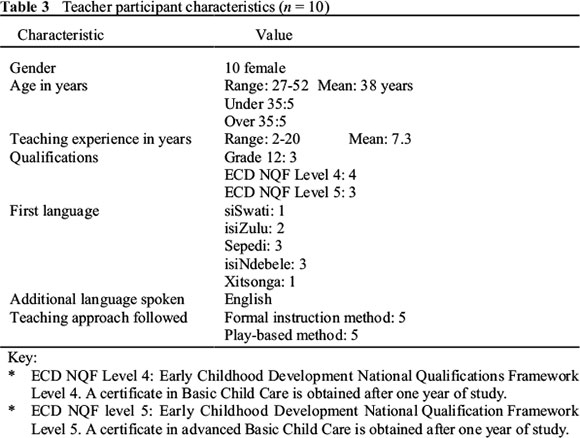

Participants

Teacher participant characteristics of the research study were captured in Table 3. The minimum qualification that teachers require to facilitate in a Grade R classroom is an ECD NQF Level 4 qualification. The criteria for selecting teacher participants were that teachers had to be registered on the Mpumalanga Department of Education's employment records, to be trained on the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements, and have at least a Grade 12 matriculation certificate. When the ten schools were randomly selected according to the two facilitation methods (play and formal instruction) in the five language groupings (siSwati, isiZulu, isiNdebele, Xitsonga and Sepedi), all teacher participants met the selection criteria.

According to Table 3 the majority of teachers were qualified since they have attained the minimum ECD NQF Level 4 qualification. There were three teachers who were in possession of a Grade 12 matriculation certificate. All ten teachers were trained on the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements in 2011 and were supported by ECD officials through periodic classroom visits during 2012. None of the teachers were first language English speakers and the diversity of their first languages was similar to the learners' first languages. The characteristics of the child participants are summarized in Table 4.

In Table 4 there were 175 child participants who gave assent to participate in the study. Their parents also submitted signed copies of the consent forms to the principal granting permission for their children to be assessed in Grade R EAL skills. Gender matching was close though it was not equally divided between boys and girls. In this study all first language groupings of learners in Mpumalanga in the selected schools were represented. Learners were matched in pairs according to gender and language grouping in the play-based and formal instruction approaches implemented in schools. The main reason for choosing different language and cultural groupings is to obtain a contextually rich dataset that is representative of all the main languages spoken in the Province. Thus matching was achieved in this research study.

Material

The criteria reflected in the ELP standards assessment tool appear to be universal and applicable to the South African context since the national Grade R curriculum emphasises the importance of listening and speaking skills for preparing the foundation for formal Grade 1 learning. However, the activities reflected in the ELP tool was contextualized to the US context and these activities would not be applicable to Grade R learners in rural Mpumalanga. Therefore, contents of the activities had been adapted to the South African context, using stories, poems, rhymes and songs commonly told and recited in rural Mpumalanga. An example of a US contextualized story used in the ELP assessment where questions were posed by the raters to learners is as follows:

Roger and Robert are good friends. They attend kindergarten. They are attending Westbrook Preparatory School. The name of their teacher is Mrs C Roberts. Roger and Robert play football in the afternoon. Their favourite meal is pizza with fresh hot chips.

The story was adapted to the rural Mpumalanga context as follows:

Siyabonga and Mpho are good friends. They are in Grade R. They attend Dumeleni Primary School. The name of their teacher is Mrs D Simelane. Siyabonga and Mpho like to play soccer in the afternoon. Their favourite food is pap, meat and gravy.

Questions

1. What is the name of the school where Siyabonga and Zama attend?

2. Which Grade are Siyabonga and Zama attending?

3. What is the name of their teacher?

4. What game do the boys like to play in the afternoon?

5. What are the boys' favourite foods?

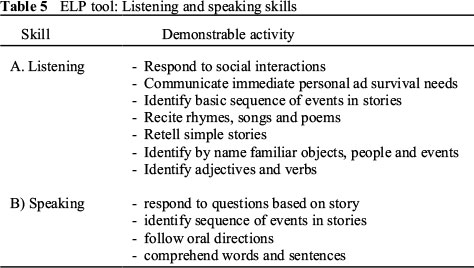

In the ELP tool learners were expected to demonstrate speaking and listening skills in the classroom which are reflected in Table 5.

Procedures

The ELP standards assessment tool was pre-tested in two rural schools (one school adopting the play-based and the other school using the formal instructional approach) that closely resembled the characteristics of the selected sample of schools. This small scale preliminary study was conducted before the main research in order to check the feasibility and user friendliness of the ELP standards assessment tool and efficiency of the teacher training to administer the tool (Creswell, 2009 ; Leedy & Ormrod, 2005). The pilot study assisted the researcher in determining whether the criteria reflected in the ELP standards assessment tool was clearly understood by the teacher participants and whether the tool was used correctly in the classroom. Even though the test was only administered in two classrooms, the learners in the formal instruction classroom achieved better results when compared to learners in the play based classroom.

Three months were allocated to collect data for the main study in the 10 schools. The teacher and researcher rated learners' EAL competency independently based on learners' demonstration of listening and speaking skills in English. The teacher and researcher indicated with a tick or cross whether child participants were able to demonstrate the specific EAL skills as reflected in the ELP standards assessment tool. All scoring was conducted unobtrusively and the children were not overtly aware that they were being assessed.

Data analysis

A one-way ANOVA was used to determine whether a play-based or a formal instruction approach (independent variables) had a statistic effect on the dependent variable (learner EAL scores) (Lomax, 2007). According to Lomax (2007), a one-way ANOVA compares groups of data according to only one factor (in this case facilitation approach, i.e. play and formal instruction). Before a one-way ANOVA could be carried out, a check on the normality of the data was conducted. The results of the Kolmo-gorov-Smirnov test demonstrated that the data was normally distributed and was arranged like a bell curve. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated a favourable result which indicated that there was no great difference between the data distribution and the general population of Grade R learners in rural Mpumalanga. A post-hoc test was conducted to determine which groups of data differ from each other.

Validity and reliability

The rationale for using the ELP standards assessment tool is that the tool has content validity since it measures the listening and speaking competencies reflected in the US Grade R curriculum. The same competencies are expected in the South African Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements (Department of Education, 2012; US Department of Education, 2007). According to Leedy and Ormrod (2005) a measurement instrument has high validity if it includes all competencies reflected in the content that needs to be assessed and includes skills that should also be demonstrated by participants during the assessment process.

The ELP standards assessment tool has been used for the past eight years and has not been revised and amended to date (US Department of Education, 2011). The performance standards and criteria embedded within the tool appear to be universal since it focuses specially on all listening and speaking skills that learners should demonstrate in the Grade R year.

The researcher organized a workshop where an information booklet was provided and a discussion occurred on how learners were to be assessed. Teachers were practically trained on the use of the tool prior to the commencement of the study and were afforded opportunities of asking clarity seeking questions. Teachers were made aware of possible issues of bias towards certain participants who were shy and were not confident to respond to the raters. The teachers were told to make their learners comfortable through constant praise and encouragement. Teachers were requested to repeat questions and instructions and tell stories, poems and rhymes three times. These issues emerged during the analysis of the pilot study's findings which was addressed when teachers were trained on the use of the ELP tool prior to the commencement of the study in the selected schools. Out of 525 assessments, there were only three instances where the researcher and the teachers' scores differed. The same training procedures that were used in the pilot schools were used in the study sample. According to Lomax (2007) rater training modifies raters' expectations of task demands and clarifies their rating criteria, thereby reducing rater variability. Inter-rater reliability was assured as another rater was used whenever there was a difference between raters.

Results

The following research question was posed in the study: What is the effect of facilitation i.e. play and formal instructional based approach on Grade R learners' EAL scores?

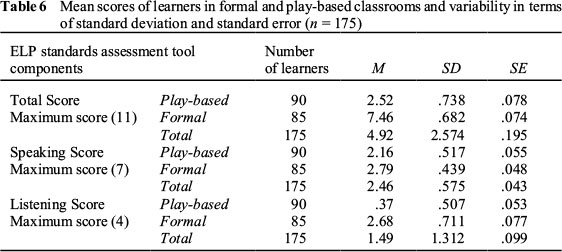

The effect of two types of facilitation methods (play and formal instruction approaches) on the Grade R learners' scores were evaluated in 175 learners in ten schools. Five schools adopted the play-based method and five schools implemented the formal instructional method. The mean scores, standard deviations and standard errors of the participants on the ELP standards assessment tool for EAL proficiency after three months of exposure to English in their rural Grade R classroom, are provided in Table 6.

In this sample 68% of all means was within 1 standard error of the population mean and 95% was within 2 standard errors. Table 6 demonstrated that performance scores were systematically higher in the formal based groups than the play-based groups. As reflected in Figure 1 the highest difference between the two facilitation methods was observed in the total and listening scores. The sharp difference in the two facilitation methods can be seen in the formal instruction classrooms where the average total score was 7.46 out of 11 while the mean total score in play-based classrooms was 2.52 out of 11.

The error bars reflected in Figure 1 indicate the observed variability using the standard error parameter. Table 6 and Figure 1 indicated that there was a small standard deviation and standard error in the study sample. The small standard deviation indicated that the data was not widely spread from its means. The sample error was indicative of a low variability of the sampling means. Apart from the differences between the two groups, the individual participant scores in each group were not widely spread, indicating that they had very similar scores.

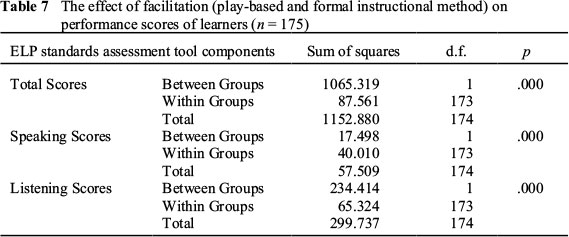

Based on the initial observation of higher scores in formal instruction as opposed to play-based classrooms, there was a need to determine whether the difference is statistically significant. A one-way ANOVA was carried out with the facilitation method (play-based and formal instruction approach) as the independent variable and the three different scores (total, speaking and listening scores) as the dependent variables.

Table 7 describes the results of the one-way ANOVA for each of the three scores (total score, speaking and listening sub scores) of the ELP standards assessment tool.

As seen in Table 7 highly significant differences (p <0.000) were observed between the two facilitation methods (play-based and formal instruction method). Learners in a formal instruction environment had significantly higher total, speaking and listening scores than learners in play-based classrooms.

The research results confirmed that learners in formal instruction classrooms performed better than learners in play-based classrooms in EAL skills. This performance of learners in formal instructional classrooms was consistently higher than in play-based classrooms. It was interesting to observe that learners were performing better in the formal instruction based approach which was not advocated by the Mpumalanga Department of Education to be implemented in the Grade R classrooms. The recommended facilitation approach (play-based) had achieved poor Grade R learners' EAL scores as reflected in Table 7 and Figure 1. The differences in participants' performance scores were mostly observed in the listening scores and not so much in the speaking scores. In the play-based classrooms, the participants obtained very poor scores for listening skills in English, i.e. listening and understanding a story in order to retell it and answer questions about it.

Discussion

In this research study learners exposed to the formal based EAL facilitation approach achieved better Grade R learner performance than learners in play-based classrooms across all the first language groupings that they represent. After four months of EAL exposure, the play-based group only scored a mean of 2.52 out of eleven, whereas the formal instructional group scored a mean of 7.46 out of eleven. It is clear that the play-based group did not learn much English during this period and could not respond adequately to questions and teacher requests. This tool tests both BICS and CALP skills. In play-based classrooms, teachers are developing learners' social language use in contrast to formal instructional classrooms where learners' academic language is being developed.

In the study, learners in formal based classrooms achieved some CALP and BICS while learners in play-based classrooms achieved some BICS only. Learners are required to demonstrate both CALP and BICS in Grade 1 learning (Mpumalanga Department of Education, 2012). Formal instruction in EAL learning may offer a solution to the poor results of EAL skills demonstrated by learners in play-based classrooms. A comprehensive approach may be required to increase EAL readiness for Grade R. There will be a need to train teachers in educational linguistics so that they can use the appropriate teaching methods to facilitate EAL learning in the classroom. There is a need to develop the children's first language as much as possible so that they can have a better linguistic foundation for EAL learning.

It appears that the participants' listening skills were much more advanced in formal instruction classrooms. Limited opportunities to learn to listen and noise interference could have contributed to the participants' very poor performance on EAL listening tasks in the play-based classrooms. According to Bowman, Donovan and Burns (2010) research globally reports that children's listening skills in the early grades were found to be under developed and the recommendation is that attention be given to improving listening competencies in Grade R children by providing them with practical exercises.

The results of the study should be seen within the context of facilitation approaches (play-based or formal instruction) employed in the classroom and its emphasis on either the social or academic language. The aim of formal instruction classrooms, in contrast to play-based classrooms, is that learners acquire the academic language, focusing on the ability to comprehend meaning of sentences and communicate in grammatically correct sentences with the ability to use the correct verb tenses and adjectives (Kruse, 2005). The play-based classrooms are concentrating mainly on singing of songs, saying poems, stories and rhymes and little attention may be given to teaching learners the academic language (Patterson, 2008).

The ELP assessment tool was designed to determine learners' EAL skills in the US (US Department of Education, 2007). With some adaptations to the contents of activities, it appears that the tool was valid to be used in rural Mpumalanga schools by both teachers and the research. The tool should be used in other context in South Africa so that more information about its reliability and validity can be determined.

Xu (2010) stated that the three pre-requisites for effective EAL Grade R learning are that teachers are proficient in English, appropriate language activities are presented and that learners are provided with much exposure to English. Based on the results of the present study, it appears that formal instruction may have promoted listening, provided more language exposure and appropriate activities than the play-based approach.

Grade R teachers should be held accountable for developing learners EAL skills since language skills have an impact on learners' subsequent performance in the early grades of schooling (Howes, Burchinal, Pianta, Bryant, Early, Clifford & Barbarin, 2008). With the Annual National Assessments conducted by the Department of Education (2012), it was found that Grade 1 learners lacked decoding and interpretative skills that are usually developed in Grade R. Xu (2010) states that new thinking in the ECD sector emphasises the need to use a valid instrument to assess learners' competency in order to plan how to address gaps in learners' EAL skills.

According to Burchinel (2009) learners are required to speak fluently in grammatically correct sentences, listen attentively and respond adequately to instructions or teacher requests at the end of Grade R. This study's findings indicate that there was a statistical significant difference between listening scores of learners exposed to play-based and the formal instruction approach. An emphasis on listening skills should be accorded high status in the national Grade R curriculum and the Department of Basic Education should consider the emphasis placed on listening in teacher education programmes at higher education institutions.

Previously there was little acknowledgement of the difference between conversational and academic language in the Grade R curriculum apart from mention of the fact that language needs to be used for thinking and reasoning (Patterson, 2008; Xu, 2010). Teachers need to be trained on the differences between academic and social language. There has been a shift from static Grade R teacher knowledge-based inservice training sessions to active and practically orientated skills based training sessions for teachers (Falco, 2005).

In summary, the first important implication of the research study for Grade R learning is that a formal instruction approach produced more EAL acquisition in the learners as measured with the ELP tool than a play-based approach. The second implication is that, based on this study, the ELP standard assessment tool was appropriate for use in a South African context.

Most of the EAL learners in rural Mpumalanga are living in poverty and their exposure to language resources in English is limited. The current findings indicate that the Grade R learners' EAL skills may be boosted with a formal instruction approach.

Numerous research questions, listed below, are still unanswered which will form the basis of further research:

1. What is the effect of teachers' first language on Grade R learners' EAL scores?

2. What is the effect of learners' first language on their EAL scores?

3. What is the effect of learners' gender on their EAL scores?

4. What is the effect of teachers' qualifications on Grade R learners' EAL scores?

5. What is the effect of teachers' age on Grade R learners' EAL scores?

6. What is the effect of teachers' experience on Grade R learners' EAL scores?

Conclusion

In this study it was found that the play-based approach produced lower learner performance scores than the formal instruction approach in Grade R. The analysis of the learner performance scores in both approaches indicate that learners' achieved higher listening scores in the formal instruction approach and achieved almost the same speaking scores. Considering that learners are second language English speakers who are attending Grade R at schools, it is recommended that the hybrid model (a combination of the play-based and formal instruction approaches) is implemented in the classroom. This recommendation is made since children acquire language (either first language or second language) both incidentally as a result of exposure to learning contexts, and as a result of explicit instruction (Heugh, 2002). In the Nevada study (Nevada Department of Education, 2009, see Table 2) there was no significant difference between learners' speaking scores which suggests that the play-based and formal instructional method could be jointly used to develop learners' speaking competency.

Although the research study was conducted in rural Mpumalanga, it has nationwide implications. The contribution of the study is to offer an approach that may be followed to address the national dilemma of Grade R facilitation practices in EAL learning. Formal instruction of EAL skills in Grade R may prepare learners for Grade 1 than play-based facilitation. EAL learning in Grade R needs to be prioritized in research as there is potential in intervention on this level.

References

Bowman BT, Donovan MS & Burns MS (eds.) 2010. Eager to learn: Educating preschoolers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [ Links ]

Burchinel MR 2009. Educational transformations. Child Development, 2(1):178-180. [ Links ]

California Department of Education 2010. Report on English language learners. California: California Department of Education. [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Cummins J 2008. BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In B Street & NH Hornberger (eds). Encyclopedia of language and education: Literacy (2nd ed., Vol. 2). New York: Springer Science. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 2002. South African Schools Act. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education 1997. Language in Education Policy. Available at http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=XpJ7gz4rPT0%3D&tabid=390&mid=1125. Accessed 13 March 2014. [ Links ]

Department of Education 2012. Curriculum assessment policy statements. Grade R-3. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Du Plessis S & Louw B 2008. Challenges to preschool teachers in learner's acquisition of English as language of learning and teaching. South African Journal of Education, 28(1):53-75. Available at http://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/6527/DuPlessis_Challenges%282008%29?sequence=1. Accessed 10 March 2014. [ Links ]

Ellis R 2008. Understanding second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Falco F 2005. Critical transformation in education. Baltimore, MD: Brooks Publishing. [ Links ]

Florida Department of Education 2010. Florida: Kindergarten English learning. Florida Department of Education. [ Links ]

Geva E 2000.Issues in the assessment of reading disabilities in L2 children - beliefs and research evidence. Dyslexia, 6(1):13-28. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200001/03)6:1<13::AID-DYS155>3.0.CO;2-6 [ Links ]

Heugh K 2002. Revisiting Bilingual Education in and for South Africa. Occasional Papers No 8. Cape Town: PRAESA. [ Links ]

Howes A, Burchinal M, Pianta R, Bryant D, Early D, Clifford R & Barbarin O 2008. Ready to learn? Children's pre-academic achievement in pre-Kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1):27-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.05.002 [ Links ]

Kapp R 2004. 'Reading on the Line': An Analysis of Literacy Practices in ESL Classes in a South African Township School. Language and Education, 18(3):246-263. doi: 10.1080/09500780408666878 [ Links ]

Kruse TC 2005. Building a high/scope preschool programme. Ypsilanti: High Scope Press. [ Links ]

Leedy PD & Ormrod JE 2005. Practical research:planning and design. New Jersey: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Lomax RG 2007. An introduction to statistical concepts for education and behavioral sciences (2nd ed). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [ Links ]

Matterson C 2009. Kindergarten curricular. New Mexico: Clancey Publishers. [ Links ]

Mesthrie R 2006. South Africa: Language Situation. Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics, 1:539-542. [ Links ]

Mpumalanga Department of Education 2012. School visit reports - 2012. Nelspruit: Mpumalanga Department of Education. [ Links ]

Nel N & Müller H 2010. The impact of teachers' limited English proficiency on English second language learners in South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 30:635-650. Available at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/viewFile/61790/49875. Accessed 10 March 2014. [ Links ]

Nevada Department of Education 2009. Kindergarten studies. Douglas: Prince Publishers. [ Links ]

Patterson C 2008. Child development. New York: Mc Graw-Hill. [ Links ]

Texas Department of Education 2008. Kindergarten learners' performance in literacy. Texas: Stratton Publishers. [ Links ]

United States (US) Department of Education 2007. Kindergarten curriculum. New York. [ Links ]

US Department of Education 2011. Report on English language learners. Washington: California Department of Education. [ Links ]

Wally S 2007. Kindergarten children's oral learning. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Ward H 2008. Preschool learning holds the key to children's success in later life. New York: TES Publishers. [ Links ]

Xu SH 2010. Teaching English language learners: Literacy strategies and resources for K-6. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

York S 2008. Kindergarten research. Illinois: Sanchez Printers. [ Links ]