Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Education

versão On-line ISSN 2076-3433

versão impressa ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.34 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

Educators' understanding of workplace bullying

Corene de Wet

School of Open Learning, University of the Free State, South Africa dewetnc@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article looks at educators' understanding of workplace bullying through the lens o a two-dimensional model of bullying. Educators, who were furthering their studies at the University of the Free State, were invited to take part in a study on different types of bullying. Deductive, directed content analysis was used to analyse 59 participants' descriptions of workplace bullying. The study found that the theoretical model provided a valuable framework for studying bullying in this context. The analysis of the educators' descriptions provided the following insights about the relational and organisational foundations of workplace bullying: (1) The relational powerless victims are subjected to public humiliation, disregard, isolation and discrimination. The bullying of educators results in escalating apathy and disempowerment, to the detriment of their professional and private wellbeing. (2) Bullying is likely to occur in schools where organisational chaos reigns. Such schools are characterised by incompetent, unprincipled, abusive leadership, lack of accountability, fairness and transparency. (3) There is interplay between relational powerlessness and organisational chaos, i.e. the absence of principled leadership, accountability and transparency gives rise to workplace bullying.

Keywords: content analysis; educators; school principals; workplace bullying

Introduction

Workplace bullying is an issue faced by many employees worldwide (Bartlett & Bart-lett, 2011), including educators (Fox & Stallworth, 2010). This is of great concern as workplace bullying in the education setting has the potential to negatively influence teaching and learning (Beale & Hoel, 2011; De Wet, 2010a). Workplace bullying may, furthermore, be a violation of employees, including educators, human and labour rights (Beale & Hoel, 2011; Le Roux, Rycroft & Orleyn, 2010).

Research on workplace bullying has increased notably during the last three decades in countries such as Sweden, Norway, Germany, Austria, Australia, and Britain (Blasé & Blasé, 2004; Fox & Stallworth, 2010). Nonetheless, very little research has been done on workplace bullying per se in South Africa (e.g. Steinman, 2003 ; Upton, 2010), or the bullying experiences of educators within the international (Blasé & Blasé, 2004; Fox & Stallworth, 2010) and South African (De Wet, 2010a) contexts. Some exceptions with regard to international research on workplace bullying in the teaching fraternity are Blasé and Blasé's (2002; 2003; 2004), Fox and Stallworth's (2010) and Cemaloglu's (2007a and 2007b) studies. Blasé and Blasé's (2002; 2003 & 2004) qualitative study looked into the experience of 50 educators who had suffered long-term bullying by their principals. Cemaloglu's (2007a and 2007b) survey among 337 primary school educators in Turkey explored the relationship between organisational health, as well as demographic variables and bullying. The aim of Fox and Stallworth's (2010) study was to view violence and the bullying experiences of educators within the stressor-emotion-control/support framework. Limited research on workplace bullying within the South African school context has been done by De Vos (2010), De Wet (2010a & 2010b), and Kirsten, Viljoen and Rossouw (2005). De Vos's (2010) qualitative study investigated the personal characteristics and behaviour of victimised educators and their bullies which may contribute to workplace bullying. De Wet's (2010a; 2010b) qualitative study focuses on the plight of educators who were bullied by their school principals. Kirsten et al.'s (2005) paper explores the bullying behaviour of educational leaders with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). Despite the scarcity of research on workplace bullying within the teaching profession, it seems to be a serious problem. Fox and Stallworth's (2010) study among 779 educators reveals, for example, that 46.5% and 19.6% of the respondents were subjected to pervasive bullying (i.e. "quite often" or "extremely often") by their supervisors and peers, respectively.

Georgakopoulos, Wilkin and Kent (2011), as well as Parzefall and Salin (2010), find that despite the growing body of knowledge on workplace bullying, researchers are not unanimous regarding what exactly constitutes workplace bullying. Le Roux et al. (2010:53) write that there is, apart from the definition of "occupational detriment", no definition of workplace bullying in South African labour legislation. Le Roux et al. (2010) find that the existing legal remedies to deal with workplace bullying - the Employment Equity Act (Act 55 of 1998), the Labour Relations Act (Act 66 of 1995), and the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (Act 130 of 1993) - do not protect employees from bullying. The absence of a clear legal framework for bullying is not a typical South African symptom; there is, for example, no federal legislation in the United States (Bartlett & Bartlett, 2011) or in the United Kingdom (Beale & Hoel, 2011) that specifically defines and protects against workplace bullying. The development of a coherent law or Code of Good Practice (Le Roux et al., 2010) to protect employees is dep endent on a clear understanding of what workplace bullying constitutes. Left unchecked, the negative effects of workplace bullying can be costly for both the company (school) and individual employees (educators) (Georgakopoulos et al., 2011).

In her study on principal-on-educator bullying De Wet (2010a) found that educators who were victimised by their principals suffered from depression, headaches, sleep deprivation, stress, and burnout. Hauge, Skogstad and Einarsen (2010), as well as Dhar (2012), likewise found that bullied employees are at increased risk of depression, alcohol abuse, prolonged duress stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and even suicide. Workplace bullying may also result in low levels of motivation and morale of the employees, increased absenteeism, and employees becoming involved in counterproductive work behaviour (Dhar, 2012). De Wet (2010a) furthermore found that bullying of educators often leads to reduced loyalty, apathy and mediocrity. De Wet's (2010a) study also revealed that educators withdraw both emotionally and psychologically from social and professional activities in order to avoid further mistreatment.

The profound negative impact of workplace bullying on employees', including educators', private and professional lives necessitates research on this topic. The aims of this article are firstly, to address the identified gaps in workplace bullying research; namely, insufficient research on workplace bullying in South Africa in general and within the teaching fraternity in particular; and secondly, to validate a relatively new model of workplace bullying. These aims will be realised by looking at educators' understanding of workplace bullying through the lens of Hodson et al.'s (2006) two-dimensional model of bullying.

I will start with an overview of the concept of workplace bullying, followed by a brief description of the theoretical framework that underpins this study before I move on to examine educators' understanding of workplace bullying.

The concept of workplace bullying Workplace bullying has been defined as

all those repeated actions and practices that are directed to one or more workers, which are unwanted by the victim, which may be done deliberately or unconsciously, but clearly cause humiliation, offence, and distress, and that may interfere with job performance and/or cause an unpleasant working environment (Einarsen, 1999:17).

Bartlett and Bartlett's (2011:72) definition reads as follows:

Workplace bullying is ... a repeated and enduring act which involves an imbalance of power between the victim and the perpetrator and includes an element of subjectivity on the part of the victim in terms of how they view the behaviour and the effect of the behaviour.

These two definitions encompass the main features of most definitions of workplace bullying: repeated and enduring behaviours that are intended to be hostile and/or are perceived as hostile by the victim (Jennifer, Cowie & Ananiadou, 2003). In contrast to many definitions of workplace bullying as an intentional act (cf. Parzefall & Salin, 2010), Einersen (1999) argues that bullying may be the result of both intentional harm-doing and unintentional disregard for the victim. The effect of the act on the victim, rather than the intention of the bully, is highlighted by Einersen (1999). The imbalance of power and/or status between victims and perpetrators is emphasised in many definitions of workplace bullying (Bartlett & Bartlett, 2011; Hauge, 2010). Although conflict may escalate to bullying if it is not managed, one distinguishing factor between conflict and bullying is the frequency and longevity of the action. An isolated incident between two parties of equal power is not considered bullying (Georgakopoulos et al., 2011; Hauge, 2010:14; Salin, 2003).

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework for this study is Hodson et al.'s (2006) two-dimensional model of bullying. They refer to the first dimension as relational powerlessness in the workplace and to the second as organisational coherence. Hodson et al. (2006:385) write that

"Power and powerlessness are not static attributes of individuals or groups of individuals. Rather, power and powerlessness are fundamentally relational in nature, defined by ongoing, if often subtle and assumed rights and relationships".

According to Hodson et al. (2006:385) the workplace is "an arena suffused by power relations". Consequently, employees who are relationally less powerful, among others those with insecure jobs, those of minority status, and those engaged in low-skilled service work, will be more likely to be bullied. The model, furthermore, seeks to illuminate how abuses of relational powers are enabled or constrained by particular organisational contexts. They argue that bullying is less likely to occur in environments with organisational transparency, accountability and capacity. Organisational coherence and managerial competence are, according to them, central to such accountability and capacity (Hodson et al., 2006).

Research approach

Samnani (2012) argues that workplace bullying can be examined through four different paradigmatic lenses; namely, functionalism, interpretivism, critical management theory, and postmodernism. Whereas non-functionalist paradigms steer away from the application of definitions for concepts/phenomena ('bullying is in the eye of the beholder'), functionalist literature seeks to identify key features of workplace bullying (Samnani, 2012). In this study I will use a qualitative functionalist approach, since it links with the aim of my study, namely, an attempt to explain workplace bullying with the help of existing theory. Although functionalism uses a diverse range of methods to investigate its research questions - qualitative and quantitative - the majority are quantitative. Samnani (2012) writes that qualitative studies, using a functionalist approach, attempt to determine whether certain types of employees (powerless versus powerful) or practices (managerial chaos) are more likely to result in bullying using qualitative data.

Data collection and participants

During 2012 I lectured a Comparative Education module (B.Ed.Hons.) at the University of the Free State. I invited educators who were enrolled for this module to take part in a study on bullying. The following introductory detail was given to the participants in a questionnaire:

Bullying includes a variety of behaviours, ranging from psychological acts (e.g. shouting) to physical assaults. Bullying can be either direct (e.g. physical and verbal aggression) or indirect (e.g. threats, insults, name calling, spreading rumours, writing hurtful graffiti, cyber bullying or ignoring the victim). The literature has identified the following types of bullying: learner-on-learner bullying; educator-on-learner bullying; learner-on-educator bullying; and workplace bullying (i.e. employees/educators being bullied by their principals, colleagues or the parents of learners).

A number of open questions were asked, but this paper focuses on the following question that was included in the questionnaire: Please share with me your experience^) as a victim and/or an onlooker of bullying.

The majority of the students (181 of205) completed the questionnaire. More than half of the 181 participants (50.3%) described incidences of learner-on-learner bullying from their perspective as educators, onlookers, and/or bystanders. Ten (5.5%) participants wrote about their childhood experiences as victims of bullying. The rest of the participants wrote about workplace bullying (32.6%), educator-on-learner bullying (9.9%), and educator-targeted bullying (7.2%). In line with the aim of this article, only the descriptions of workplace bullying were analysed.

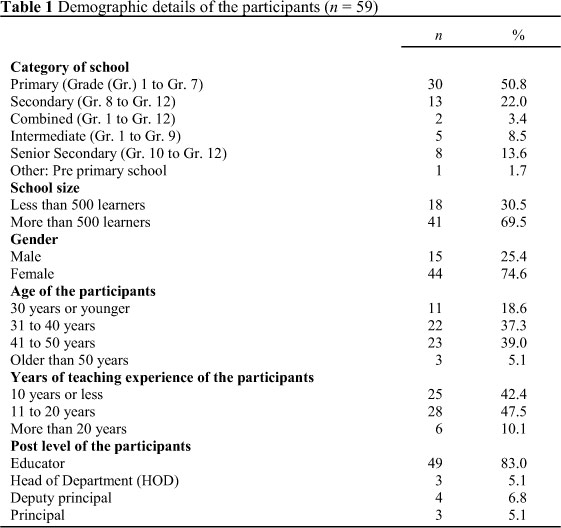

Table 1 gives a summary of the demographic details of the students who wrote about their experiences of workplace bullying.

Most of those who wrote about workplace bullying, namely, 40 ofthe 59 (67.8%), described their own experiences as victims of workplace bullying. The rest ofthe participants either described the victimisation of members of staff in general, e.g. "the educators at our school" or "we were too afraid to ask questions", or wrote from the perspective of onlookers, e.g. "we were too afraid to stand up for our colleague" and "nowadays she is afraid to raise any point". The foregoing percentage is typical of the research on workplace bullying. Hauge (2010) finds, for example, that an important characteristic of research and theorising on the concept of workplace bullying is that it is studied from the victim's perspective.

Ethical measures

The participants' dignity, privacy and interest were respected at all times. The questionnaires did not contain any identifying aspects, names, addresses, or code symbols. Before completing the questionnaires, the students were also informed that the process was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any stage during the process. I was present during the completion of the questionnaires at all times. In the introductory section of the questionnaire I invited participants who felt traumatised because of issues arising from the questionnaire to contact me. I undertook to put them into contact with a therapist. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Research Office, Faculty of Education, University of the Free State. The head of the School of Education Studies gave permission for the study to be conducted with B.Ed.Hons. students.

Data analysis

Elo and Kyngäs (2007), as well as Hsieh and Shannon's (2005) guidelines for deductive, directed content analysis were used to analyse educators' descriptions of workplace bullying. My decision to use directed content analysis was motivated by the aims of this study; namely, to validate an existing theory on workplace bullying and expand the research on the bullying of educators. Content analysis using a deductive, directed approach is guided by a more structured process than a conventional approach (Elo & Kyngas, 2007). Using existing theory and prior research, I began my analysis by identifying key concepts as initial coding categories. Next, operational definitions for each category were determined using Hodson et al.'s (2006) two-dimensional model of bullying. Thereafter, I read through all the scripts and highlighted all texts that, on first impression, appeared to represent educators' understanding of workplace bullying. The next step was to code all the highlighted passages using the predetermined codes. Any text that could not be categorised with the initial coding scheme was given a new code. Thereafter, I compared the extent to which the data were supportive of Hodson et al.'s (2006) model.

According to Hsieh and Shannon (2005:1281) the strengths of a directive approach to content analysis is, firstly, that existing theory can be supported and extended and, secondly, that researchers are "unlikely to be working from the naive perspective that is often viewed as the hallmark of naturalistic designs". The aforementioned researchers, however, highlight the following limitations of this approach: (1) Researchers approach the data with an informed, but nonetheless strong bias. Researchers may therefore be more likely to find evidence that is supportive than non-supportive of a theory. (2) An overemphasis of the theory may blind researchers to contextualise aspects of the phenomenon. These limitations may hamper the trustworthiness of the findings of the study. I therefore went to great lengths to enhance the trustworthiness of my study: (1) I avoided generalisations - the aim of the study was to seek insight into the participating educators' understanding of workplace bullying. (2) I chose my quotations carefully and reproduced enough of the text to allow the reader to decide what the participant was saying. (3) By stating the limitations of the study upfront, readers will have a better understanding of how I arrived at my conclusions. (4) To facilitate transferability, I gave a clear description of the selection of the participants, as well as data gathering and analysis methods (Elo & Kyngäs, 2007).

Findings and discussion

An analysis of the written responses of the participants revealed that, in accord with Hodson et al.'s (2006) two-dimensional model of bullying, workplace bullying is manifestations of relational powerlessness and organisational chaos. In the discussion of the findings of my study, I will link the findings with the work of other researchers; an acknowledged and widespread practice among qualitative researchers (cf. Burnard, 2004).

Workplace bullying is a manifestation of relational powerlessness Most definitions of workplace bullying focus on the superior-subordinate relationship between the parties involved in a bullying relationship. Lutgen-Sandvik (2003:473) describes workplace bullying, for example, as "a repetitive, targeted, and destructive form of communication directed by more powerful members at work at those less powerful". The power that the more powerful member holds can be defined as "disproportionate control over other individuals' outcomes as a result of the capacity to allocate reward and administer punishment" (Fast & Chen, 2009:1406). In the ensuing discussion, attention will be given to the different ways participants' descriptions supported the first dimension of Hodson et al.'s (2006) model; namely, that workplace bullying is an embodiment of relational powerlessness. The discussion of relational powerlessness will focus on the role-players, the different ways in which the powerful perpetrators assert their power over their powerless victims, the impact of the bullying on the victims, and the different educational contexts in which the bullying takes place.

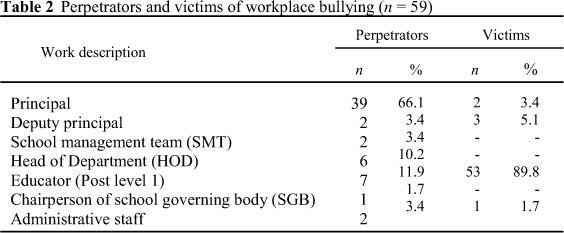

Table 2 gives a summary of the perpetrators and victims of workplace bullying.

Data for Table 1 were extracted from the participants' descriptions of incidences of workplace bullying, as well as the demographic details supplied by them.

The results from Table 2, namely, that principals are the main perpetrators of workplace bullying and that they target those with lesser status (Post level 1 educators), are confirmed by the narratives, as well as previous research on workplace bullying in general (Beale & Hoel, 2011) and the teaching fraternity in particular (Blasé & Blasé, 2004; De Wet, 2010b; Fox & Stallworth, 2010). Participants wrote about principals who mocked, shouted, threatened, and humiliated them. The power of the bully is encapsulated in the following description: "He is not a manager or a leader. He is a boss". The vulnerable victims lacked job-security (remunerated by the SGB and non-permanent educators) and/or were breadwinners, beginner-educators with study loans/ bursary obligations, newcomers (redeployed), and/or pregnant. The powerlessness of the victims is aptly illustrated by a beginner-teacher who kept quiet despite being relentlessly bullied by his HOD: "I was desperate to keep my job". Victims of bullying are not always those appointed in so-called lower status jobs. A beginner-educator wrote about the school secretary who "used me as her punch bag when she is in a bad mood". A newly appointed principal said he was subjected to "threats, name-calling, insults and a plot to put me to death" by members of the SGB. Victims furthermore, seem to be those who do not fit in. A Xhosa-speaking educator who taught at a predominantly Sesotho-speaking school wrote that "they [his colleagues] wanted me to feel that I don't belong here and that I am not going to get the [promotion] post". Another participant, who taught at a private school, wrote that she was bullied because "I don't belong to their church". Salin's (2003:1219) notion that perceived power imbalances are not necessarily due to formal power differences, but the result of "situational and contextual characteristics" resonates well with this study.

The narratives of the participants abound in examples of how bullies abuse those who are relationally less powerful than they are. Verbal abuse seems to be the most common type ofworkplace bullying: "the principal uses verbal aggression and shouts at his subordinates"; "I was mocked by the principal"; "he talks to her rudely"; and "the principal laughed at me". A deputy principal noted that his principal "shouted at me and called me names". An educator who wrote about her bullying HOD said that there were often notes "on my desk about how inefficient I was". The spreading of malicious rumours seems to be a favourite tactic of bullies: "This lady always gossips about me to other staff members and reports each and every thing I do to the deputy principal". Another participant noted that a colleague who bullied the school principal and wanted to undermine the principal's authority "spread malicious rumours that the secretary and the principal had an affair".

Threatening behaviour seems to be a common bullying tactic (e.g. "He talks to educators in a threatening manner"). The threats ranged from inflicting serious bodily harm on the victims ("a plot to put me to death"), to reducing their fringe benefits and threats of instant dismissal if they questioned their bullies' judgement and/or instructions. It should be noted that only one participant made reference to bullying that might have endangered the victim physically. The rarity of physical harm-doing as a form of workplace bullying is confirmed by the literature (Blasé & Blasé, 2002; De Wet, 2010a; Salin, 2003).

Another way that bullies assert power over the victim seems to be their disrespectful demeanour towards those they do not hold in high esteem; for example, the bully "treats us like children; he doesn't treat us with respect" and "makes me feel small". This disrespect is demonstrated in the way bullies intentionally ignore their victims by not greeting them, blatantly ignoring them when they want to say something during meetings or casual conversations, and when they pass each other in the corridors.

Social isolation (e.g. "If I join the group they willjust disperse"), favouritism (e.g. "principals must stop taking sides" and "favouritism is common in our school") and nepotism ("home-girl" and principal's daughter), were also identified by participants as features of workplace bullying. Blasé and Blase's (2004) and Bartlett and Bartlett's (2011) studies also suggest that social isolation and favouritism are common forms of workplace bullying.

Two of the participants wrote that they were bullied by proxy. One of them said her colleagues spread vicious rumours about her assessment methods among parents. Consequently, parents visited her at school or phoned her to criticise her marking and demanded that she reassess their children's work. The other one wrote:

I have been bullied by one of my colleagues. Instead of disciplining the bully, my principal encouraged her in what she was doing. My bully is even humiliating the learners that I am teaching. She is telling a lot of lies about me to the principal.

This study has thus shown that an imbalance of power results in the powerless being subjected to an array of verbal abuses and threats. The educators who took part in this study were humiliated, disrespected, socially isolated, and discriminated against by those who were more powerful than them.

The powerlessness of the victims of bullying is emphasised in participants' descriptions of where the bullying took place. The verbal abuse of educators by their principals took place in their classrooms in front of their learners (a participant wrote that her school principal often did class visitations unannounced and "She will interrupt you as a teacher... by correcting what you say in front of the children, even shouting at you" and "She [the principal] came to my class and shouted at me in front of my learners"); during assembly ("The principal shouted at me at the school assembly . She used vulgar language in front of the pupils and other teachers"); during staff meetings ("She is always bullied during staff meetings by the principal"); in front of colleagues ("She verbally abused me in front of my colleagues"); and "He shouts at me in front of the other teachers". The following quotation illustrates how a personal grudge against an educator was settled in public:

He [the principal] wanted to have an affair with the lady. But the lady didn't want to.

...when promotion posts were advertised, she applied, but she was not successful. She was told that her application forms were not received. The principal destroyed them.

The public humiliation of educators in front of others is not an uncommon bullying tactic (cf. Blasé & Blasé, 2004). The public ridicule of educators in front of their learners and colleagues is disempowering and may have long-lasting effects on them, including embarrassment, a loss of respect from their learners, also depression, stress and burnout, and health related problems such as headaches and sleep deprivation (cf. De Wet, 2010a).

The autocratic, abusive management style of school principals regularly results in apathy among members of staff (e.g. "We ended up not saying anything during meetings. He could hold a meeting on his own" and "nowadays she is afraid to raise any point".) Fear of the bully may result in victims handing over their power to the bully: "we are afraid to face reality.we pretend to understand him; we are too afraid to ask him to explain if he tells us something in the staffroom". Whereas one of the victims internalised being ignored and being reduced to being "a nobody", another one wrote that she felt "so small". The powerlessness of the victims of bullies is manifested in their inability to defend themselves against their bullies. The emphasis of the participants on the negative effect of the bullying acts on the victims links well with Einersen's (1999) seminal definition of workplace bullying.

The importance of the power differences between principals and educators "cannot be overstated" (Blasé & Blasé, 2004:169). The next section will focus on how bullies (mostly school principals) abuse their power, because they have reward and coercive powers such as professional development opportunities, promotion, workload, as well as appointment and dismissal of SGB remunerated and non-permanent educators.

Workplace bullying is a manifestation of organisational chaos

The second dimension of Hodson et al.'s (2006) model of bullying seeks to address the problem of how organisational chaos and managerial incompetence enable workplace bullying. Organisational dynamics, especially an organisation's culture and leadership, may 'allow' and sanction workplace bullying (Duffy & Sperry, 2007; Hauge, 2010; Salin, 2003). Cemaloglu (2007a) identifies the following criteria for unhealthy schools that can be linked to 'organisational chaos': aggression; incompetent school administrators; and conflict and communication gaps between educators. The following discussion will support the theoretical framework underpinning this study and illustrate how incompetent and unprincipled managers abuse formal, bureaucratic structures to bully educators. The discussion will also focus on the bullies' unfairness, lack of transparency in the work environment, and the discrediting of the professional lives of the victims.

Consistent with the findings by Blasé and Blasé (2002), Cemaloglu (2007a), Fast and Chen (2009), De Wet (2010a), and Einarsen (1999), this study has found that ineffective leaders often bully their subordinates. Several participants made mention of the unprofessional, dishonourable conduct of their principals, e.g. "When I was on sick leave he confiscated my medical certificates and threatened me with leave without pay"; "she delays to sign documents"; and "Myprincipal wants us to do what he says, even if he is wrong". The lack of principles as an underlying cause of bullying was also implied by an experienced educator, who was responsible for her school's budget. She was ostracised by the SMT because she strictly followed procedures with regard to the dispersal of funds. The following quotation illustrates that workplace bullying goes hand-in-hand with a lack of transparency and dishonesty:

Our principal threatened us that we are going to lose ourjobs because one ofour colleagues reported him at the [Department of Education] DoE for some things that he did wrong at the school. We all knew that he was wrong, but we were too afraid to stand up for our colleague because we had to have a lie detector test and we knew that he always has a way of getting away with things and he was going to make things very difficult for us at work if we sided with our colleague. We left the matter just like that and he ended up winning the case.

The above quotation illustrates how educators' lack of knowledge of grievance procedure and their right to fair labour practices (Rossouw, 2010) perpetuates workplace bullying. The South African Council of Educators (SACE) (2002), as well as the leading teachers' trade unions in South Africa (cf. Heystek & Lethoko, 2001), set out to create a work environment where dignity and respect are afforded to all educators. The SACE and the teachers' trade unions also undertake to tackle incidents that violate educators' rights speedily and effectively. However, victims of bullying often decide not to confront their tormentor or turn to official organs to protect them against their bullies (De Wet, 2010a). This may lead to a spiral of silence. Several participants moreover suggested that their bullies abuse official structures to bully them by denying leave, fringe benefits, promotion and/or permanent appointments. Whereas three participants wrote about being refused special leave to write examinations, another participant's principal was unsupportive of her request for sick-leave: "I was told that my leave-paper will be refused as sick-leave because there is no reason to be absent from school or to be in the hospital during the first term." Another participant noted that her request to make a doctor's appointment during school hours was turned down. The principal told her "just hold on till school is out because the doctors are only closing at 17h00". The abusive task-orientated principals' emphasis on official procedure exposes their lack of sensitivity to personal matters. Blasé and Blasé (2004:161) write in this regard that bullying principals routinely discount educators' "thoughts, needs and feelings". Duffy and Sperry's (2007) finding, namely, that bullying thrives in organisations that are bureaucratic and/or rule-orientated, is confirmed by the current study. Bullies, who abuse formal structures in organisations that allow bullying, often perceive their bullying behaviour as "merely a tough management style" (Georgakopoulos et al., 2011:14) and "an effective means of accomplishing tasks" (Salin, 2003:1221).

Workplace bullies strive to tarnish the professional image of their victims. A female educator, for example, was told by the deputy principal that she was incompetent and "cannot teach", despite the fact that she had had a 91% Matric pass rate the previous year for Accounting. Her teaching responsibilities for Accounting were taken away from her and given to a person "with no teaching diploma". A young educator who made an administrative error was told that she was "not a good teacher; I don't know how to teach and he stopped me to teach that subject [Natural Science]". A participant wrote with empathy about her friend and colleague who was demoted after a jealous colleague spread lies about her. Educators who took part in Blasé and Blase's (2004) study also mentioned that they were unfairly criticised by their superiors.

The withholding of important information, such as departmental circulars, memoranda, workshops and appointments with learning facilitators was mentioned by several participants as ways used by bullies to create the impression that they are not capable and/or diligent educators. Bullies furthermore set their victims up to fail by, amongst other things, interrupting their classes or regularly changing the grades and/or learning areas they have to teach. The latter prevents them from becoming experts. A young educator recalled how he was, when he first arrived at the new school, forced by colleagues to teach learning areas and classes that he did not want to teach. He wrote: "sometimes I did not have a clue but because I was under strict command I had to obey them". An educator who was redeployed noted that she was bullied by colleagues at her new school. They forced her to teach subjects and be responsible for extramural activities of which she had no knowledge. The findings from this study, namely, that bullies set their victims up to fail and appear incompetent seems to be a fairly common bullying tactic (Blasé & Blasé, 2004; De Wet, 2010b).

Participants furthermore complained about work overload, as well as harsh demands. While one of them wrote that her principal often expects "too much" from her, to the detriment of her family, another said that her principal demanded from her "... to complete that work or I will be dismissed". It furthermore became evident that bullying principals demand that educators perform tasks that may be detrimental to their health and safety. Whereas one participant wrote that she was forced to attend a school function that started at 18:00 in an area that she perceived to be unsafe at night, another participant wrote that she was once bullied by the principal into taking learners to the funeral of the parent of a fellow-learner. The latter noted that it was "a very far place...and I had to go on foot regardless of my ill health". Blasé and Blasé's (2004: 161) study also found that principals often make unrealistic demands and that they are often "shamelessly unfair".

Narratives by the respondents illustrated bullies' disregard for boundaries between the professional and private lives of their victims. A participant, who taught at a private school, noted that the female principal at her school "even set rules on our attire as teachers; we were not allowed to put on makeup or nail polish, or to wear trousers". A female educator wrote the following about her HOD:

"I have been recently appointed. At first things went smooth, until she called me and 'chose my friends for me'. She did not like the one I choose for myself. She began to criticise my way of dressing".

Findings from this study have shown that organisational chaos may lead to what Bart-lett and Bartlett (2011) call the workload (work overloaded, removing responsibility, delegation of menial tasks, refusing leave, unrealistic goals, setting up to fail); the work process (flaunting status/power, professional status attack, controlling recourses, withholding information); and evaluation and advancement of bullying (judging work wrongly, unfair criticism, blocking promotion). Note should nonetheless be taken of Salin's (2003:1216) observation that "not all acts that can be used as bullying tactics are necessarily perceived as bullying per se". He argues as follows:

Isolated occasions of being given tasks below one's level of competence, being given a tight deadline or not being asked to join colleagues for lunch or another social event would most likely be seen as normal and neutral features of work life. However, such acts may become negative, and thus bullying, when they are used in a systematic manner over a longer period, resulting in an unpleasant and hostile work environment (Salin, 2003:1216).

Concluding remarks

In this paper I explored educators' understanding of workplace bullying through the lens of Hodson et al.'s (2006) two-dimensional model of bullying. The theoretical model provided a valuable framework that incorporates individual and organisational levels for the studying of bullying. The analysis ofthe educators' descriptions provided the following insights about the relational and organisational foundations of workplace bullying: (1) The relational powerless, namely, the vulnerable and those whose situa-tional and contextual characteristics do not fit in, are vulnerable to bullying. They are subjected to verbal abuse and threats. The powerless are publicly and privately humiliated, disrespected, socially isolated and discriminated against by those who are more powerful than them. The relentless bullying of educators results in escalating apathy and disempowerment, to the detriment of their professional and private wellbeing. (2) Bullying is likely to occur in schools where organisational chaos reigns. Such schools are characterised by incompetent, unprincipled, abusive leadership, a lack of accountability, fairness and transparency. (3) There is interplay between relational powerlessness and organisational chaos, i.e. the absence of principled leadership, accountability and transparency gives rise to workplace bullying. This model however, fails to acknowledge the influence of broader societal factors on workplace bullying. The interaction between, for example, the abuse of power by school principals and violence in the community or corrupt school management and questionable government actions needs to be interrogated in future research.

References

Bartlett JE & Bartlett ME 2011. Workplace bullying: an integrative literature review. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(1):69-84. doi: 10.1177/1523422311410651 [ Links ]

Beale D & Hoel H 2011. Workplace bullying and the employment relationship: exploring questions of prevention, control and context. Work, Employment & Society, 25(1):5-18. doi: 10.1177/0950017010389228 [ Links ]

Blasé J & Blasé J 2002. The dark side of leadership: teacher perspectives of principal mistreatment. Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(5):671-727. doi: 10.1177/0013161X02239643 [ Links ]

Blasé J & Blasé J 2003. The phenomenology of principal mistreatment: Teachers' perspectives. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(4):367-422. doi: 10.1108/09578230310481630 [ Links ]

Blasé J & Blasé J 2004. School principal mistreatment of teachers: eachers' Perspectives on Emotional Abuse. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 4(3/4):151-175. [ Links ]

Burnard P 2004. Writing a qualitative research report. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 12:176-181. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2003.11.006 [ Links ]

Cemaloğlu N 2007a. The relationship between organizational health and bullying that teachers experience in primary schools in Turkey. Educational Research Quarterly, 31(2):3-29. [ Links ]

Cemaloglu N 2007b. The exposure of primary school teachers to bullying: an analysis of various variables. Social Behaviour and Personality, 35(6):789-802. [ Links ]

De Vos J 2010. Personal characteristics and behaviour of victimised educators and their bullies that contribute to workplace violence. Unpublished MEd dissertation. Potchefstroom: North-West University. [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2010a. The reasons for and the impact of principal-on-teacher bullying on the victims' private and professional lives. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(7):1450-1459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.tate.2010.05.005 [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2010b. School principals' bullying behaviour. Acta Criminologica, 23(1):96-117. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/crim_v23_n1_a8.pdf. Accessed 13 December 2013. [ Links ]

Dhar RL 2012. Why do they bully? Bullying behaviour and its implications on the bullied. Journal of Workplace Behavioural Health, 27(2):79-99. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2012.666463 [ Links ]

Duffy M & Sperry L 2007. Workplace mobbing: individual and family health consequences. The Family Journal, 15(4):398-404. doi: 10.1177/1066480707305069 [ Links ]

Einarsen S 1999. The nature and causes of bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2):16-27. doi: 10.1108/01437729910268588 [ Links ]

Elo S & Kyngas H 2007. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62:107-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [ Links ]

Fast NJ & Chen S 2009. When the boss feels inadequate: power, incompetence, and aggression. Psychological Science, 20(11):1406-1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02452.x [ Links ]

Fox S & Stallworth LE 2010. The battered apple: An application of stressor-emotion-control/support theory to teachers' experience of violence and bullying. Human Relations, 63(7):927-954. doi: 10.1177/0018726709349518 [ Links ]

Georgakopoulos A, Wilkin L & Kent B 2011. Workplace bullying: A complex problem in contemporary organizations. International Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(3):1-20. Available at http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._3_%5BSpecial_Issue_-_January_2011%5D/1.pdf. Accessed 13 December 2013. [ Links ]

Hauge JL 2010. Environmental antecedents of workplace bullying: A multi-design approach. Unpublished PhD thesis. Bergen: University of Bergen. Available at https://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/4309/Dr.thesis_Lars%20Johan%20Hauge.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 13 December 2013. [ Links ]

Hauge LJ, Skogstad A & Einarsen S 2010. The relative impact of workplace bullying as a social stressor at work. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(5):426-433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00813.x [ Links ]

Heystek J & Lethoko M 2001. The contribution of teacher unions in the restoration of teacher professionalism and the culture of teaching and learning. South African Journal of Education, 21:222-228. Available at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/view/24907/20519. Accessed 17 December 2013. [ Links ]

Hodson R, Roscigno VJ & Lopez SH 2006. Chaos and the abuse of power: workplace bullying in organizational and interactional context. Work and Occupations, 33(4):382-416. doi: 10.1177/0730888406292885 [ Links ]

Hsieh H & Shannon SE 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9):1277-1288. [ Links ]

Jennifer D, Cowie H & Ananiadou K 2003. Perceptions and experience of workplace bullying in five different working populations. Aggressive Behaviour, 29(6):489-496. doi: 10.1002/ab.10055 [ Links ]

Kirsten GJC, Viljoen CT & Rossouw JP 2005. Bullying by educational managers with narcissistic personality disorder: a health protection and psycho-legal issue? Paper presented at the South African Education Law and Policy Association (SAELPA) Conference, Bloemfontein, 4-6 September. [ Links ]

Le Roux R, Rycroft A & Orleyn T 2010. Harassment in the workplace: Law, policies and processes. Durban: LexisNexis Butterworths. [ Links ]

Lutgen-Sandvic P 2003. The communicative cycle of employee emotional abuse: Generation and Regeneration of workplace mistreatment. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(4):471-501. doi: 10.1177/0893318903251627 [ Links ]

Parzefall M & Salin DM 2010. Perceptions of and reactions to workplace bullying: A social exchange perspective. Human Relations, 63:761-780. doi: 10.1177/0018726709345043 [ Links ]

Rossouw JP 2010. Labour relations in education: a South African perspective (2nd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Salin D 2003. Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Human Relations, 56(10):1213-1232. doi: 10.1177/00187267035610003 [ Links ]

Samnani A 2012. Embracing new directions in workplace bullying research. A paradigmatic approach. Journal of Management Inquiry, 22(1):26-36. doi: 10.1177/1056492612451653 [ Links ]

Steinman S 2003. Workplace violence in the health sector. Country case study - South Africa. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

South African Council of Educators 2002. Handbook for the code of professional ethics. Available at http://www.pmg.org.za/docs/2002/appendices/020521handbook.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2003. [ Links ]

Upton L 2010. The impact of workplace bullying on individual and organisational well-being in South African context and the role of coping as a moderator in the bullying-well-being relationship. Unpublished MA dissertation. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. Available at http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/8385/LEANNE%20UPTON%20-%20MA%20DISSERTATION.pdf?sequence=2. Accessed 17 December 2013. [ Links ]